This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

There is a lesson in every disaster. Now that the hysteria has quieted in Houston, we can survey the ruins left by the Great Castration Fiasco. When a young black man named Steve Allen Butler offered to place his testicles on the scales of justice, he began a debate that spread through Texas and soon across the entire country, illuminating the divisions between classes, races, and genders. Concerns were raised about the Constitution and medical ethics. Charges were hurled and mud was slung. The image of the state of Texas was damaged by the sneering of the national press. And yet the question that no one in this broad argument seemed willing to address was exactly what we should do with our sex offenders.

If one thing is clear in this whole messy episode, it’s that what we’re doing now is a failure. Again and again, critics have said that castration is not an effective answer to sexual offense. So far no one has asked, “Compared with what?” Today there are nearly eight thousand sex offenders in Texas prisons. Their crimes include indecent exposure, sex with minors, incest, aggravated sexual assault, and rape. Yet only two hundred are receiving counseling—an indication of how little faith we place in therapeutic solutions. Given the turnover in our prisons, most of those offenders will be out on the streets after serving a small portion of their sentences. More than half will be arrested for another sex crime in fewer than three years.

We may despise the people who commit such acts, but we should realize that most of them are victims themselves, not just of childhood sexual abuse but of their own overwhelming sexual impulses. As was evident in the Butler case, some of the offenders are crying out for another form of treatment. They want to be castrated. Until we find a better solution, perhaps voluntary castration of sex offenders is a good idea.

The debate began last fall at a dinner party in Tanglewood. “Like every gathering I’ve been to in Houston recently, the subject of crime captured the whole conversation,” recalls state district judge Michael McSpadden. Everyone complained that the courts were failing, that crime was out of control—even though these were the people least affected by the city’s decay. “They were the lucky ones,” says McSpadden. “They could all afford private patrols and burglar alarms and security systems. And yet they felt captive in their own homes.” McSpadden shared their frustration. Seven out of ten people he was sending to prison had already been there before. Increasingly, many criminals were choosing prison rather than probation, knowing that in Texas the average internment is 23 days per year of sentence, whereas probation can last for years. “If they get a seven-year term, they’ll do less than seven months and be released from the Harris County jail,” the judge says.

McSpadden is a blue-eyed ex-Marine given to wearing ties that have American flags on them. In ten years on the bench, he has been rated the best judge in Harris County by the Houston Bar Association, the county deputy sheriffs, and the Houston police. He has also become one of the county’s top vote-getters. But like many Houstonians, he sometimes thinks about living somewhere safer. “This isn’t the same city I moved down to years ago,” he says. “The quality of life in Houston is simply unacceptable. Harris County is a war zone.”

It was at that dinner party that Dr. Louis J. Girard mentioned his then-unpublished paper on castration. Girard is a vigorous 73-year-old eye surgeon who codesigned the first corneal contact lens in 1958. “I’m appalled by the increase in crime,” he says, “and I’m scared to death for my wife and children and grandchildren. We’ve got guns all over the place.” He tells a story that has become all too familiar in Houston. “One of my patients, a little Vietnamese girl, was operating a convenience store. She was robbed, and after they took the money out of the cash register, they threw ammonia in her eyes.” The woman’s experience confirmed Girard’s belief that “these people are animals and they ought to be treated like animals.”

Being a scientist, Girard decided to examine what factors influence criminal behavior. “A lot of crime is based on high levels of testosterone,” he concluded. This powerful hormone determines a man’s body shape, his hair patterns, the pitch of his voice. “It also produces aggressiveness in the males,” Girard told the judge. “It is the reason that stallions are high-strung and impossible to train, the reason male dogs become vicious and start to bite people. It’s why boys take chances and chase girls, why they drive too fast and deliberately start fights. In violent criminals, these tendencies are exaggerated and carried to extremes.” In Girard’s opinion, castration would reduce and possibly eliminate such aggressive impulses. “The castrated criminal would be more docile and have a better opportunity to be rehabilitated, educated, and to become a worthwhile citizen,” Girard contended.

Girard’s idea rang a bell with McSpadden. If there was a painless, inexpensive procedure that would reduce the overflowing prison population, allow criminals to gain control over their violent natures, make them more susceptible to rehabilitation, and also act as a powerful deterrent to other offenders, what could be wrong with that?

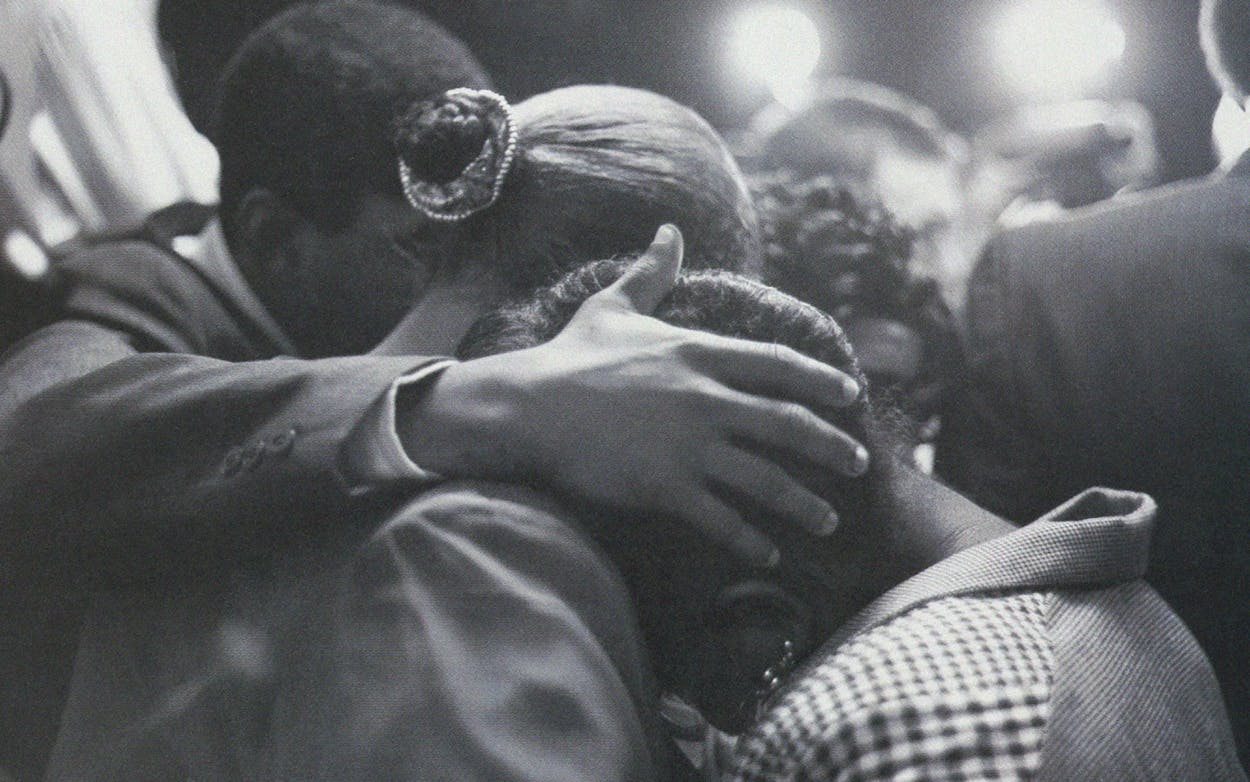

Soon after that dinner party, McSpadden and Girard became castration evangelists, carrying their message to television stations, call-in radio shows, Rotary lunches, and black churches in the city. They preached the need to pass legislation allowing juries to impose surgical castration as a punishment for violent offenses. Quickly, the proposal ignited the national talk shows and the local media. “Castrating criminals has no place in American justice,” the Houston Post editorialized in September. “Fortunately for those men and women Girard would like to see go under the knife, the Eighth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution—the one that prohibits cruel and unusual punishments—almost certainly bars such action.” Robert C. Newberry, a black columnist for the Post who prides himself on being moderate and reasonable, immediately called the plan barbaric and racist: “Would Girard be proposing such a thing if a great percentage of the white male population were locked away in prison?” The general counsel to the Houston chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union, Bruce Griffiths, compared Girard’s plan to the selective breeding programs of Nazi Germany.

The controversy might have died out soon after that except for 27-year-old Steve Butler, who read about it in the paper in October. At the time, Butler was sitting on the fifth floor of the Harris County jail, accused of having had sex with a 13-year-old girl. Butler was already on probation in McSpadden’s court for fondling a 7-year-old girl in 1989. The new charge could result in a lengthy prison term. Butler might get life, plus 10 years for violating his probation. He had already rejected the plea bargain offered by the assistant district attorney handling the case, Bill Hawkins, in which Butler would plead guilty to aggravated sexual assault and receive 35 years. Because it was an aggravated charge (meaning that the victim was under 14), Butler would have to serve at least one fourth of his time before he would be eligible for parole. He would spend the next 8 years and 9 months in prison as a convicted child molester, the lowest rung on the criminal hierarchy.

Steve Butler is quiet and slender, with a soft choirboy’s face and a high boxy flattop that looks like a sawed-off fez. Handsome and wide-eyed and slightly retarded, he could easily be mistaken for a teenager, even with his faint moustache and goatee. Butler grew up in Houston, the baby boy of ten children born to a construction worker. In the eleventh grade he dropped out of school when his girlfriend became pregnant. That was the first of four children Butler has fathered. In 1982 he started shining shoes at K&M Hair Design in the tunnel of the Bank of the Southwest building. He held that job for nine years, making $455 every two weeks.

Butler’s problem, as he later admitted to psychologists who examined him, was that he had no control over his sexual impulses. Dr. Michael Cox, a well-respected therapist at Baylor College of Medicine who counsels sex offenders, examined Butler at Judge McSpadden’s request. After administering a battery of standard psychological tests, Cox found Butler to be mildly depressed but otherwise sane and competent. Butler “didn’t look any different from the garden-variety child molesters I see in the program,” says Cox. “He had been abused when he was young. He seemed to be more of a situational offender—in other words, his sexual preference is for adult women. But he does have a drinking problem, and if there is a female child available and he’s been drinking, one thing can lead to another.”

The victim in the latest case is a neighbor of Butler’s grandmother. The victim’s mother has known Butler all his life. Moreover, she isn’t eager to have her daughter testify. She’d rather see Butler castrated than have the case go to trial.

Butler himself had recently settled into a steady relationship with a woman he called his wife. Terra Cook was about to bear him a child. Although castration could end her sexual life with Butler, Cook said she would still rather have her husband at home providing for her and their child than locked in prison until the end of the decade. Under the deal the court had structured, if Butler were castrated, the judge would place him on ten years’ strict probation. Although castration is not a sanctioned punishment for sex offenses in Texas, judges have broad powers of discretion in plea-bargain arrangements. However unusual the deal may have been, there was nothing illegal about it.

As for Butler, his motives were varied. “I just think it would help me a whole lot,” he admits. “I could be a better person. I could go on with my life and take care of my family.” He is also frightened by the idea of going to prison, especially as a child molester. “I’ve heard stories about it,” he says in a near whisper. “Some say it’s hard. You have to fight.”

“Frankly, I think the judge is titillated by the idea of cutting the balls off a black man,” says the Reverend Jew Don Boney, the chairman of the Houston chapter of the Black United Front. “This is McSpadden playing God. It’s unprecedented; it’s outside of normal legal bounds; and it introduces a whole new level of inhumanity into the criminal justice system.”

Soon after the news of Butler’s decision hit the papers, Boney and Frank Burns, then head of the state conference of the NAACP, held a press conference and called for McSpadden’s resignation. “This is merely an effort to set a precedent and open doors of opportunity to castrate thousands of black males legally,” Burns said.

That was just the beginning of an angry assault on the judge by black men. State Representative Ron Wilson threatened to initiate impeachment proceedings against McSpadden if the operation took place. “I don’t think you’d see Judge McSpadden offering this type of sentencing to people in River Oaks,” said Wilson. The NAACP threatened a convention boycott of Houston.

Castration is a profound symbol of the historic oppression of black men. In 1855 the Territory of Kansas introduced judicial castration of Negroes and mulattoes who raped or attempted to rape white women. In the South, blacks were sometimes castrated before being lynched. “It’s a reminder of what I read about in the days of slavery and in the late eighteen-hundreds and early nineteen-hundreds,” says Burns. “If this is the best we can come up with in terms of punishing or trying to deal with people guilty of that type of crime, then I’m wondering what changes we have made between 1892 and 1992.” “It’s just too close to an ugly part of our history,” says Robert Newberry. “You would have to have gone through that type of history to really feel the emotional impact of how our forefathers were treated.” Newberry recalls seeing a photo of a lynched black man with a bloody gash where his sex organs had been. “This castration issue brings it all back. It stirs up the pain. ”

For many black people, the contrast between the white judge—a maverick Republican who plays tennis at the Houston Racquet Club—and the shine man sitting in the jailhouse seemed to characterize the imbalance of power between the races. One had privilege and the respect of society; the other was a high school dropout with no prospects, the sort of castoff that society notices only when he becomes a statistic in the criminal justice system. What was there left to take away from Steve Butler—except his manliness?

That Butler himself sought castration was rarely commented upon, except to say that he was a victim of judicial coercion. In fact, McSpadden had been elaborately cautious in making sure that Butler’s choice was free and informed. He instructed Butler to talk to four psychiatrists and therapists, including Michael Cox, who was outspokenly opposed to the castration option. No one was able to change Butler’s mind. He still preferred castration to prison, a choice denounced as “a very dangerous precedent” by Frank Burns. And yet when I asked Burns what he would do if he were in Butler’s place, having to choose between a lengthy spell in prison or castration, he said he “may very well” make the same choice: castration and freedom.

“I’d give anything if Mr. Butler were white and in another court than mine,” McSpadden admits. He was wounded by the accusations of racism. “It hurts, because I do a lot of work in the black community.” For several years, he has devoted every Friday afternoon to making inner-city children aware of the consequences of drugs, teenage pregnancy, and crime. He often leads field trips through the courthouse and the holdover cells. His walls are lined with plaques and certificates from schools, thanking him for his support. Moreover, he thinks his reputation as a “hard-time judge,” one who is likely to hand out severe sentences, does a favor to black citizens. “By far the largest proportion of crime victims I see are black. That’s what’s so disturbing to me about these so-called ‘black leaders.’ The heart and soul of the black community is crying out for leadership to protect them.”

“People hear the word ‘castration’ and it scares them,” McSpadden told me one afternoon in his chambers. “They don’t realize it is a simple surgical procedure that can be done on an outpatient basis. It’s not cutting off the penis. It’s far less intrusive than a hysterectomy. What’s more, the crime we see in Texas is a direct result of the failure of present punishments to serve their intended purposes of retribution, rehabilitation, and deterrence. If castration does work, then we not only let that person live a normal life because of a simple medical treatment, but we also protect society from that same person for years to come.”

In the background, the judge had a television on, to catch the national news. He was expecting a report on the Butler case. Instead there was a story that reflected black male attitudes—in this case, black churchmen—about Mike Tyson’s sentencing hearing for his rape conviction. They felt Tyson should go free. “It’s because he’s an Afro-American. He’s a brother of ours,” Tyson’s supporters were saying. McSpadden looked at me and rolled his eyes.

The judge was interrupted by his bailiff, who brought in a question from the jury in a case currently on trial. McSpadden put on his robe and returned to his court to hear testimony read back to the jurors. A blank-faced young black woman was charged with aggravated robbery and attempted capital murder. The jury had been hung eleven to one for conviction most of the day.

“I’ve been to too many crime scenes and talked to too many victims of violent crimes,” McSpadden said when we returned to his chambers. “I’m not willing to give up and hand over our city to criminals. People call castration barbaric. They say it’s not suitable for civilized society. Let me tell you something: We don’t live in a civilized society. Last year in Houston alone twenty-five hundred children were reported raped. There’s no way in the world you could call that a sign of civilization. How dangerous does it have to get before we as a society are ready to protect our men and women and especially our children by effectively dealing with our violent offenders?

“We could construct a law so that it would be the option for a judge and jury to say we think castration is suitable in certain cases. If we could apply it in cases where a deadly weapon is used, you’d see a lot of weapons left at home. Anyone who uses a knife or a gun in the commission of a crime ought to be castrated. ”

“What about that young woman in your courtroom right now?” I asked.

“Take out her ovaries!” the judge said. “Dr. Girard tells me that ovaries produce testosterone in women. ”

“What you’re talking about is sterilizing criminals,” I said.

“That’s right. That’s exactly what we’re talking about.”

“A nun called,” reads an entry in the judge’s voluminous phone log. “Was raped and brutalized and still afraid because they haven’t caught them. Is 100 percent for this.” “Lady called. Afraid to give her name because she was raped. Why don’t you run for president?” “We need more people in the justice system like you. Can we lobby to get public hangings at courthouse after they are castrated?” “Man called. Suggests you do it with a lawnmower.”

It was clear from the hundreds of calls and letters that the castration issue strikes a deep chord of fear and anger and a longing for revenge. That is exactly what worries Cassandra Thomas, the director of the rape program at the Houston Area Women’s Center. “I don’t think castration should be used as punishment,” she says. “It only buys into the myth that sexual assault is about sex, and so therefore if you get rid of sexual desires you get rid of rape. The reality is that sexual assault is about violence; it’s about a need for power and control. It has nothing to do with the genital organs.” Castration, she says, is “an empty symbolic gesture.”

“I was sexually assaulted eight years ago this June,” remembers Donica Vincent, a counselor at the center. “It was by a dear friend. You’d never think he would rape me, but before it was said and done, he had hit me, shattered glass over me, and I was bleeding vaginally. In my particular case, even if the perpetrator had been castrated that wouldn’t have dealt with why he was so violent. He still could have done all those things without penetrating me. The perpetrators no longer need a penis as a weapon.”

Many women see rape as a political act, evidence of the male need to control the female. Viewed through that lens, treating the problem by removing the sex organs will only frustrate men and make them, as Thomas argues, “more likely to use violence as a way of dealing with their issues of inadequacy and powerlessness and helplessness that perpetuate sexual assaults in the first place. ”

In the end, that which seemed to be most personal to Steve Butler—his testicles—somehow turned out to be a part of the public trust. They were too valuable to other interests for Butler to have a say in their removal. “This young man has an IQ of sixty-nine,” says the NAACP’s Frank Burns, “and I would question his competency in making such a decision.” Apparently, Burns thinks that he and Reverend Boney should do Butler’s thinking for him. “As a survivor of rape,” says Vincent, “I would think he was getting off too easy.” “Medical castration will not work because it does not deal with the issue between their ears, only with the issue between their legs,” says Thomas. But if castration did work, Thomas admits, she would still oppose it. “It’s only a stopgap measure. What are you going to do—castrate every man who has a problem?”

Inadvertently, Butler had stepped onto the stage of the collective unconscious. Perhaps because public discussion of sexual deviance is shunned in our country, we tend to demonize sex offenders, especially child molesters. They are outcasts even among criminals. There is no question as to the damage they do to their victims and to society. But in the hysteria that surrounded the Butler case, no one bothered to see who Butler really was. He had become a precedent, and worse for him, a symbol. To black men, this unassuming pedophile had become a symbol of black manhood. To feminists, this aspiring family man had become a symbol of sexual oppression. To the judge, this baby-faced boy who is afraid of fighting had become a symbol of the tide of violence that threatens to overwhelm American society. Everyone had a sincere reason for seeing Butler as something other than himself. Even Butler’s own family would finally come to believe that he was tricked into being a pawn in a white conspiracy. No wonder then that the battle over Steve Butler’s balls would have nothing to do with Steve Butler.

Nearly everyone involved in the Butler case—like nearly everyone in Texas—has had some experience with castrated animals. The district attorney of Harris County, Johnny Holmes, keeps a herd of Longhorns, and he has personally castrated many of them. “My experience is that they get a lot bigger and a lot gentler,” says Holmes. Girard castrated bulls when he was young; he also played polo at the Bayou Club. “Believe me, there’s a tremendous difference in the amount of control you have between a gelding and a stallion.” Recently one of his German shepherds became cantankerous and nipped Girard’s daughter and his niece. “So I just castrated him, and he stopped.” Michael Cox, the Baylor sex therapist, had his cat castrated. “He doesn’t get into fights about female cats, but he still fights over territory.”

Many opponents of castration have called it uncivilized, comparing it to the Islamic fundamentalist practice of cutting off a thief’s hand. “Castration has historically been used by brutal and repressive regimes,” says Robert Fickman, a Houston attorney who filed a brief on behalf of the Harris County Criminal Lawyers Association protesting the action in McSpadden’s court. Yet in modern times, castration of sex offenders has been effectively tried in Denmark, Germany, France, Switzerland, Holland, Iceland, and some provinces of Canada—scarcely countries one would consider under repressive regimes. Two features distinguish these programs from the uncivilized practices that Fickman and others cite. First, they are voluntary; and second, castration has been seen as treatment, not as punishment. Many of these countries were following the lead of the U.S., where voluntary therapeutic castration began around the turn of the century. An aptly named Dr. Sharp castrated 176 prisoners in Indiana with the goal of subduing their sexual drives. The operations were declared unconstitutional in 1921, but soon thereafter the idea caught on in Europe.

Voluntary castration became legally permissible in Denmark through the Access to Sterilization law of 1929, which permitted the operation on a “person whose sexual drive is abnormal in power or tendency, thus making him liable to commit crimes.” Although the Danish law did permit forced castrations, that provision was never put into practice and was subsequently eliminated. Other European countries implemented similar voluntary programs. In this country, Oklahoma allowed forced castration of repeated felons convicted of crimes involving “moral turpitude”—a larger category than sex offenses—until the U.S. Supreme Court declared its law unconstitutional in 1942. Recently bills were knocked down in Washington, Alabama, and Indiana that would have permitted sex offenders to be castrated in exchange for a reduction in their sentences. The historical associations make it difficult to talk about castration without the specter of government-imposed sterilization becoming a part of the argument. Unfortunately, that is exactly the way Girard and McSpadden have framed their proposal.

Dr. John Bradford of the Royal Ottawa Hospital in Canada says that as a rule, the recidivism rate of sex offenders (that is, their likelihood to offend again) averages 80 percent before castration, dropping to less than 5 percent afterwards. In Europe, many studies on the consequences of therapeutic castration show essentially the same thing—that it is profoundly effective in lowering the rates of repeated sex offenses. A 1973 Swiss study of 121 castrated offenders found that their recidivism rate dropped to 4.3 percent, compared with 76.8 percent for the control group. In Germany, a similar report showed a post-operative recidivism rate of 2.3 percent for sex offenses, compared with 84 percent for non-castrates. Various Danish studies have followed as many as 900 castrated sex offenders for several decades; they show that recidivism rates drop to 2.2 percent. What is also important is that 90 percent of the castrated men reported that they themselves are satisfied with the outcome. “The main conclusion to be derived from all this material on castrated men,” wrote Dr. Georg K. Stürup, chief psychiatrist of Denmark’s Herstedvester Detention Center, in 1968, “is that a person who has suffered acutely as a result of his sexual drive will, after castration, feel a great sense of relief at being freed from these urges.”

These studies echo a similar experiment conducted in California, where between 1937 and 1950, 125 sex offenders were voluntarily castrated. A follow-up report of 46 of those men in 1957 found that none had been arrested for subsequent sex offenses. By comparison, in the U.S. today, according to the Department of Justice, the chances are 50 percent that a sex offender will be rearrested within three years.

Throughout the debate, opponents have theorized that castrated men might commit other crimes, and perhaps more serious ones, presumably out of their rage at being deprived of their sex drive. Nearly every study that compares recidivism rates for nonsex as well as sex crimes shows a drop in all rates of offense. The exception is the Stürup report on 38 rapists, 18 of whom were castrated. Six of those men later committed a nonsexual crime; on the other hand, none of the castrated rapists ever committed another sex offense.

“Yeah, you can castrate a horse and settle him right down,” says Dr. Cox, “but you’re not going to undo a criminal personality by playing around with a person’s hormone level.” When the Butler case first became public, Cox’s oppostion was widely quoted. “Nowhere in the world is castration being used this way,” he mistakenly told the Houston Chronicle. “This is a throwback to primitive thinking and I’m embarrassed it’s coming up in Houston, Texas.” He had been cited repeatedly as an expert who believed that castration had not been proven effective and might even backfire—that is, that the castrated offender could become more violent without a sexual outlet. At the time, Cox hadn’t read the European studies, so I asked him what evidence he had for his theory. “We’re doing a literature search,” he told me. “I’ll let you know what I find.” When his search was finished, he gave me an abstract of a Czechoslovakian study published in February 1991. It said:

The authors examined 84 castrated sexual delinquents after a 1–15-year interval following castration. 18% of the subjects were capable of occasional sexual intercourse. 21% . . . lived in a stable heterosexual partnership. . . . Only three men committed another sexual offence after castration. These offences did not have an aggressive character. . . . The authors did not observe serious physical or mental consequences of castration in the examined men. Castration must be considered even nowadays an important part of the therapeutic arsenal in sexual delinquents.

Many people who oppose castration believe that the main problem sex offenders have is psychological, not physical. Therefore, they assume, diligent treatment involving therapy and the latest behavior modification techniques should make a difference. In fact, when counseling succeeds, it is only with a very limited group. It’s an inside joke among sex counselors that if you want to have a successful program, you fill it with incest perpetrators, whose reoffense rate is about 3 percent, and keep out all the difficult cases, especially the rapists.

Nearly everyone who works with sex offenders recognizes that there are two essential preconditions for successful therapy: the admission that there is a problem and the expressed desire for help. Only a small portion of the sex offender population gets that far—and unfortunately, many fail to get the help they need. A wide-ranging 1989 review of offender recidivism in North America and Europe in the Psychological Bulletin came to the dismal conclusion that “there is no evidence that treatment effectively reduces sex offense recidivism.” The rate of recidivism, as it turned out, was often higher for treated offenders than for untreated ones.

To read that report is to realize how many approaches have been tried without success. In Florida, which was a pioneer in sex offender counseling, men who completed treatment were subsequently rearrested for a sex offense at a rate of 13.6 percent, while those who did not complete the counseling were arrested at only 6.5 percent. The group that fared best were men who were thought to be amenable to treatment but never actually got into the program. Of that group, only 5 percent were rearrested for sex crimes. Of 224 offenders in Philadelphia randomly assigned to either probation with treatment or probation only, those who were not counseled reoffended at less than half the rate of those who were. Thirty homosexual pedophiles in Canada received intensive classical conditioning treatment with biofeedback and electrical aversion therapy, but 20 percent were rearrested for new crimes against children.

“We’re getting better as we’ve learned what we’re doing,” Dr. Cox insists. “Toward the middle eighties we sharpened up our interventions.” One of the programs that researchers point to is the cognitive-behavioral program run by W. L. Marshall and H. E. Barbaree at the Kingston Sexual Behaviour Clinic in Kingston, Ontario. Marshall and Barbaree recently published a study of selected male pedophiles who went through the latest in intense invasive therapy. Sexual preferences were measured by penile plethysmography—that is, a mercury-filled rubber tube attached to the subject’s penis, which senses even minute arousals while the man watches pornographic slides of naked males and females ranging from age 3 to 24. The men were then given scores that determined their level of deviance. Treatment included electric aversion (a shock whenever an inappropriate fantasy was presented); self-administered smelling salts when the subject experienced a desire to molest children; and “masturbatory reconditioning,” which involves masturbating to orgasm while holding an image of an adult partner in mind. Only one of three test groups, molesters of nonfamilial female children, showed significant evidence of improvement after treatment, and that only after four years.

In a separate survey of other treatment programs, Marshall and Barbaree concluded that some were effective with child molesters and exhibitionists, but none were with rapists; and they also found instances where sex criminals fared better when they were simply left alone. The best of the prison programs was Vermont’s, where of 147 pedophiles released, only 3 percent committed a sex offense during the next six years. “Even allowing for the fact that the selection procedures for this program have chosen potentially low rate reoffenders, this is still below expectations for incarcerated child molesters,” the authors found.

No doubt there is progress in the field of sex offender treatment. No doubt some offenders are susceptible to treatment and others are not. But the stark fact is that none of these programs compares in effectiveness with castration.

The cost of our failure to treat sex offenders can’t be known or measured, only guessed at. The tendency to sexually offend is usually lifelong. The chances of ever being arrested for a sex crime are very small—2 percent by some measures. “I went twelve years without being arrested, but I never went more than three days without acting out,” an exhibitionist told me. The sheer number of offenses buried in the term “recidivate” can be imagined by a ten-year study of 550 sex offenders (many of whom had never been arrested), which asked each perpetrator how many victims he could specifically identify. The tally was 190,000 victims.

There is another danger involved in offender counseling, which is that it may lead to worse, not better, behavior. Dr. Paul A. Walker, who runs the Gender Clinic of the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston, reported on four patients who received psychotherapy for one form of offending and who went on to commit worse crimes. “One exhibitionist became a rapist after covert sensitization was used to rid him of exhibitionist fantasies,” Walker writes. “A voyeur, treated elsewhere, after dynamic-insight-oriented therapy, became an exhibitionist: after this was treated with electric shock aversion therapy, he engaged in pedophilic activity. Prison interrupted his career as a pedophiliac and gave him 5 years to rehearse a new masturbatory fantasy. The potential witnesses to his fantasized pedophilia (his victim children) were slain and dismembered to prevent their giving evidence against him in the future. When released from prison the voyeur-exhibitionist-pedophile was, in his erotic fantasy life, and potentially in reality, a pedophiliac lust murderer.”

Opponents of surgical castration point to another treatment, often erroneously called chemical castration, which is actually a form of drug-induced suppression of testosterone. Many European countries have turned to the use of artificial hormones in conjunction with psychotherapy as an alternative to surgical castration. In the U.S., Walker has been one of the leaders in the experimental use of medroxyprogesterone acetate, or MPA, a drug sold under the name Depo-Provera. It is an artificial female hormone that has been used as a birth control pill. Walker believes that Depo-Provera is “considerably more effective than psychotherapy alone, and even more effective than surgical castration,” although no actual comparative studies have been done. Testosterone levels of men who take the drug on a weekly basis typically fall to prepuberty levels. “Most patients experience a vacation from their sexual drive and are able to begin working on other issues in their lives,” one researcher noted.

Yet there are two significant problems with the chemical approach. One is that it depends on men who show up every week to receive their injections. Clinics that provide MPA injections are plagued by dropouts, and without the shots testosterone levels quickly rise to pretreatment levels. The other problem with chemical treatment is that it produces side effects. In a study titled “The Texas Experience With Depo-Provera: 1980–1990,” three authors from the UT Medical Branch reported on forty men who received the injections. Beyond the fact that seven of those men reoffended while they were being treated, four had gallstones, three had diabetes, and three had hypertension, among many other less serious complaints.

Compare these effects with those reported in men who were surgically castrated. In a German study of 1,036 castrated offenders, a small portion of the men gained weight, especially around their hips and chest; the skin became softer; facial hair diminished, but head hair did not change; 42 percent experienced slight complaints about hot flashes; and fewer than one third became depressed. One man developed osteoporosis, a degenerative bone disease common in women after menopause and in all elderly persons. In a different study, osteoporosis was diagnosed in 81 percent of castrated men, and it is by far the greatest medical problem; however, balance that against other social concerns: Only 24 of those 1,036 German men recidivated, with a single sex offense.

The pressure was building on Steve Butler. The Reverend Jesse Jackson came to Houston and was allowed to see Butler, even against Butler’s request not to see any visitors. Butler still wouldn’t talk about his case. “This is not just a Houston matter, just as Selma was not just for Alabama,” Jackson proclaimed outside the jailhouse, thus putting the matter of Butler’s voluntary castration on a par with the civil rights movement. “We shall make a broad public appeal here and around the country, because such a precedent would be an ugly and dangerous precedent. Rape is sickness. Castration is sickness. The judge’s complicity is sickness. We must break this cycle of sickness.”

Butler’s family, at the suggestion of Reverend Boney, had retained their own attorney, Charles Freeman, to represent their interests. Freeman is a thin man with an elegant, rather oriental white beard, who invokes a prayer to Allah whenever he speaks to the press. The day before Jackson’s visit, Freeman held a press conference to announce that Butler had changed his mind and wanted to go to trial, which did not turn out to be true. Freeman also filed a motion claiming that “castration and its equally shocking complement, hysterectomization, are David Duke–ish social de-mongrelization schemes devised by eccentric right-wing lunatics and intentionally aimed at African-American males and African-American females, respectively.” The nascent men’s movement, represented by Austin attorney Hugh Nations, decried castration as “one of the more barbaric examples of the way our culture brutalizes males.” A urologist called the operation a “mutilation” and said no respected doctor would perform it. (Actually, men suffering from testicular cancer are routinely castrated and receive a ceramic prosthesis that makes the surgery undetectable.) The New York Times weighed in with an editorial that drew heavily from Cassandra Thomas’ argument. “True, removing Mr. Butler’s testicles will reduce his sex drive,” the Times intoned. “But is it going to decrease his hostility toward women in general and little girls in particular? Possibly not. Castration might even increase it.” (In fact, there is no basis for such a theory.)

In the meantime, publicity about the case had another, unexpected effect. Suddenly the judge and the district attorney, as well as the Board of Pardons and Paroles, began receiving letters from prisoners in the Texas Department of Corrections begging to be castrated. Some of them were clearly angling for an early ticket out of prison, but there was a plaintiveness about their letters that indicated the level of desperation so many sex offenders feel. “I am currently serving time for indecency with a child,” wrote Larry D. McQuay to Judge McSpadden. “I don’t want to molest children anymore, and am undergoing TDC’s Sex Offender Treatment Program (SOTP) but would like to be treated with Depo-Provera or surgical castration as well as the SOTP therapy.” McQuay did a survey of prisoner attitudes in his wing of the Ramsey II Unit. “Of the 34 inmates and officers polled,” he reported, “79.4 percent were for surgical castration being a treatment for inmates; 20.6 percent were against it.”

“The SOTP psychiatrist seems to be offended that ‘his’ program is not working for me,” McQuay wrote in a separate letter to me. “What I can’t seem to get across to them is that it is helping, but I want to take all the precautions I can to prevent myself from reoffending. Even though I was only convicted of indecency with a child, one time, I have molested over 200 children from the ages of 18 months to 17 years old, male and female. Most of the children were assaulted many, many times over, so the number of assaults is well over 1,000 most likely much higher. I was only caught once, and now I can’t get all the treatment I want. ”

Meanwhile, in Dallas, a man accused of sexually assaulting two girls seven months after being released from prison, said he would prefer castration to prison. “If you cut off a man’s desire to have sex whatsoever, that should solve the problem,” Andrew Jackson, a 52-year-old white man, told a reporter. The prosecutor refused his offer, but it is clear that the castration issue in Texas isn’t going to go away with the Butler case. It is also clear that Butler himself is not going to be castrated, despite his own wishes. The surgeon who had volunteered to perform the operation backed out when the publicity became too intense. Another doctor called the judge’s office and left word that he’d be happy to perform the procedure for free, but on investigation the man turned out to be a dentist.

It was, finally, the lack of a surgeon that caused McSpadden to resign from the case. The weekend before he did so, he agreed to meet with Butler’s five sisters and their attorney. “I told them step by step what had happened, but they were convinced it was a white conspiracy to railroad their younger brother,” says McSpadden. The sisters were demanding that Butler be granted probation, which the prosecution had no interest in offering.

Now Butler’s case will go to another court. If the victim’s mother agrees to let her testify, Butler may be convicted and sent to prison for a long time. He may decide to reconsider the state’s offer of 35 years and expect to be out in about a decade. If the victim doesn’t testify, Butler will be a free man—free, but probably unchanged. The likelihood that he will reoffend is high even if he does join the eight thousand sex offenders we are currently incarcerating. Because eventually Butler will be back in society, as will the rest of them. Nothing that we are doing with the offender population has made any real difference in their lives; on the other hand, what sex offenders are doing to us, the rest of society, is seen every day in the courts and hospitals and rape crisis centers and child treatment programs—the circle of tragedy touches us all, somehow, if only in the financial burden of caring for the victims and jailing the perpetrators. We do a sorry job even of that.

Now that the Butler case is out of the news, perhaps it’s time to think about whether voluntary castration has a place in the treatment of sex offenders. It is a mistake to make castration a punishment, as Girard and McSpadden have proposed; the Supreme Court would probably rule it unconstitutional, and in any case it is simply too offensive to too many people. Moreover, it should be limited to sex offenders. Castration does lower testosterone, which influences aggressive and violent behavior, but taking away the sex drive won’t make a bad man good. It should be reserved for those men with uncontrollable sexual urges. In the case of pedophiles, when they exercise their sexuality they violate the law, not to mention the damage they do to the children. What good is their sexuality to them? If they want to be relieved of it, why can’t they be?

Most sex offenders are white; this is a crime where blacks are not overly represented in the prison system. There is no reason for this to be a race issue or even a class issue, since sex offenses cut across economic lines as well. “If I saw some semblance of evidence that this would work, I’d be for it,” Robert Newberry admitted after the Butler case cooled off, “but let it start with a white man.” Given the history of castration in this country, that may be a fair request.

Finally, it is a foolish consistency to castrate women for sexual or other crimes. There can be a change in behavior after such an operation, but so far it has never been correlated with sex crimes. That said, the fact is that women can have their Fallopian tubes tied as a contraceptive measure or their entire uterus removed as treatment for premenstrual syndrome, while men who rape or molest children or expose themselves up to thirty times a day can’t be castrated because that would be barbarous.

“Why can’t it be like abortion, available on demand?” one offender asks. That seems a reasonable question. As it stands now, the only way Butler could be castrated is if he gets a sex-change operation. Society poses no objection to that.

We should acknowledge that men who seek castration are making a sacrifice. The way we can do so is by reducing their prison time and giving them adequate adjustment counseling. The critics may be right that some men may reoffend, but everything we know about the subject suggests that castration works better than any other approach. Why can’t we honor the plea of Steve Butler and many other men and give them the help they are begging for? Castration may not be an ideal solution, but if we treat it as therapy rather than punishment, as help instead of revenge, and if we view offenders as troubled victims, not monsters, then perhaps the castration option will be seen as evidence of our wisdom and humanity, not of our backwardness and cruelty.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Medicine

- Longreads

- Houston