This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

I zip up my brown motorcycle jacket, a custom-tailored garment with yellow safety stripes down the sleeves. I toss a lighter leather jacket to Marta, my brown-skinned, 98-pound wife, and we go downstairs, out to the back porch, where my 500-pound Harley-Davidson Sportster has languished for ten days. Marta mounts the bike’s Naugahyde seat behind me, and we blare off, headed across town for a visit. It hasn’t been ninety days since I bought the bike—to do a story on the Bandido motorcycle club—and some of my friends haven’t seen it yet.

In a ranch-style house with composition shingles and a carport on a gently winding, gently sloped residential lane in tree-shaded West Austin, Jim Johns Mackie,* a small, redheaded, 31-year-old self-employed engineer, sits with his colleague, Tim,* on a stiff-backed Early American couch. They are watching the Dallas Cowboys, their team, in a sultry showdown with the St. Louis Cardinals. Mackie, whose shyness gives way only to an occasional, always subtle quip, is in a rare roaring mood today. The game has been a real foot-stomper, and at the end of four quarters, as Jim Johns opens another Sunday afternoon beer, the score is tied, 21–21. The game will go into sudden-death overtime, and the two fans celebrate by lighting another joint. It’s really a cliff-hanger of a game.

As the Cowboys and Cardinals line up for the kickoff, Jim Johns gulps at his can of Coors. The Cowboys push the Cardinals and the Cardinals push back, and neither team is moved much toward the great divide until the Cowboys finally kick a field goal. Jim Johns slumps back on the couch in relief, but Tim, who has other appointments to keep, rises and says so long. The Cowboys have won, 24–21, but Jim Johns Mackie is left alone.

Despite his natural reticence, Jim Johns Mackie dislikes solitude, and his solitude is especially repugnant right now, when he wants to share his high spirits. He decides to visit a woman friend. He staggers out the kitchen door to the carport, where he plops down in his red Toyota pickup. As he backs it out onto the street, he tells himself for the thousandth time that the Toyota is a sorry, contrary, squeaky little heap; he does not remind himself that it is also lethal. This afternoon, “sudden death” is only a football term to Jim Johns Mackie.

“The medic feels for my pulse. It is gone. He wraps a blood pressure gauge around my arm. Nothing registers. One of the cops lays a palm on my sweaty, cold forehead. This is the first time he’s had to watch over a dying man.”

A few blocks away, I stop the motorcycle at a self-service gas station. Marta slides off the seat, unshouldering her archaic camera. As I pump the gas, she takes photos of me, the first pictures made with the bike. When the tank is full, we ride off.

The sun is behind us and crisp autumn air blows briskly past our cheeks. Marta tightens her grasp around my waist and does not let loose until I downshift for a stoplight ahead. About fifty yards beyond, the road weaves under a freeway ramp. On the grassy median at the entrance to a winding curve stands a forest of cement pilings that support the ramp overhead. When the light turns green, I shoot away. A Celica and a blue pickup follow more slowly behind us.

Though we cannot see it—the pilings block our view—on the other side of the overpass, a red Toyota pickup is coming west. Its driver, Jim Johns Mackie, is alone; his friend was not at her apartment, and he is heading home. He steers the pickup into the curve, then passes out, foot on the accelerator pedal. The Toyota bumps against a curb on its right, then veers across the road, jumps over the curb around the median, and darts into the forest of pilings, then leaps out on the blacktop in the eastbound lane, about ten feet in front of my motorcycle.

I see a red blur—that is all, the only warning—and then we hit, head on. My handlebars snap and I’m thrown into the Toyota’s windshield, then bounced to the pavement. Marta flies over me and lands on the Celica as it swerves to avoid the wreck. The blue pickup strikes the Celica from behind, and the jolt pitches Marta from the Celica’s windshield to the street. She lies there, limp. I am barely conscious, and it is difficult to breathe.

The impact revives Jim Johns Mackie. He peers through his pickup’s shattered windshield, frightened by what he sees: he is facing west in the eastbound lane. He yanks hard on the steering wheel and guns his motor, forcing the Toyota across the median. Its suspension groans, for the frame is bent, and its radiator hisses steam as he prods the hobbled pickup to a shoulder of the road, where he parks. Jim Johns Mackie crawls out. As he slams the door behind him, he realizes that he hit us and that we may be dead.

Several cars have pulled over on the opposite shoulder, and little groups of onlookers are clumped around Marta and me. Someone is directing traffic around us, and someone else has gone to call an ambulance and the police. Marta is sitting up in the road, bloodied and dazed. There is a gash on the back of her head and one of her cheekbones is crushed. When she recognizes me, lying in the road about 25 yards away, she asks in a faint voice what has happened and why I don’t move. No one answers. She feels around on the pavement for a missing shoe but can’t find it. She tries to rise, but bystanders put their hands on her shoulders, holding her down.

Jim Johns Mackie wanders over and inserts himself into the little throng around me. He leans down, sticking a hand beneath my nose to find out whether I’m still breathing. He staggers away toward Marta but goes only close enough to see that she is alive and moving. When the police come, the bystanders point him out.

The policemen part the little crowds, telling people to back off. One of the cops kneels beside me and lays a palm on my sweaty, cold forehead. This is the first time he’s had to watch over a dying man—not the sort of duty that attracted him to police work. Then he glances back over his shoulder to make sure that Jim Johns Mackie hasn’t walked away.

An ambulance reaches us within ten minutes, and behind it comes a white car carrying a supervisor for Austin’s city-owned Emergency Medical Service. A decade ago, when funeral homes operated emergency vehicles, ambulances were little more than station wagons with stretchers. The drivers, though perhaps adept at high speeds and sharp turns, were in most cases medically unskilled. Today’s ambulance is practically an emergency room on wheels; its attendants are trained paramedics. The supervisor sends one paramedic to Marta’s side while he and the other go to work on me.

The medic cuts away my motorcycle jacket with chrome shears. He feels my wrist for a pulse. It is gone. They wrap a blood pressure gauge around my arm. Nothing registers. At my carotid artery, the supervisor counts a pulse: about 138 beats a minute—too fast and weak, indicative of shock. My left leg is turned sideways at the hip, and my right leg is skewed below the knee, but what worries them most is that my abdomen is distended—a sign of internal bleeding—and my breathing is labored. I moan about pain in my chest.

Using a radio inside the ambulance, the paramedic consults a physician at Brackenridge Hospital. The doctor orders an intravenous feeding of Ringer’s lactate, a solution for replacing blood. After they have begun the IV, the supervisor and the paramedic strap a splint on my right leg and scoop me up from the ground with a hinged stretcher that latches together behind my back. They lift me into the ambulance and set up a temporary traction rig of aluminum splints, nylon cords, and steel ratchets. As the ambulance pulls out, the paramedic lays an oxygen mask over my face and tapes the wires of a heart monitor to my chest. En route to the emergency room, he is able to measure my blood pressure—sixty over forty, too low for optimism.

“Jolted almost to sobriety by hitting us, Jim Johns Mackie watches ambulances take Marta and me away. ‘The important thing,’ he counsels himself, ‘is to cut my losses.’ When the police approach him, he demands his lawyer.”

Marta’s eye is swollen shut. She is apprehensive by the time the second ambulance arrives, because she does not understand what has become of me. On the way to the hospital, she whimpers incoherently. As the ambulance attendants carry her into the emergency room, she begins vomiting. Before they lay her down, she loses consciousness.

At the scene of the accident, Jim Johns Mackie pivots, his hands in the back pockets of his jeans, his lips pursed, his eyebrows bent in thought. As he watches the little crowds thin out, he tells himself that there is now nothing he can do to help Marta and me. “The important thing,” he counsels himself, “is to cut my losses.” When the two policemen approach him, he is ready.

“Can you tell us what happened?” one of the cops asks in that tone that suggests you’d better tell.

“Well, I lost it going around that curve,” Mackie mutters, pointing to the westbound lane.

“Show us where you were when you hit that motorcycle,” the cop grunts.

“I don’t remember,” Mackie mumbles.

“Just how much have you been drinking?” the second cop snaps.

“I’m not going to answer any more questions until I talk to my lawyer,” Mackie shoots back. One of the cops unhooks the handcuffs from his belt and clips them around Jim Johns Mackie’s wrists.

There is a jungle of tubing around my bed. Plasma runs down a plastic vine to a vein in one arm, and a glucose solution drips through a second tube to the other arm. A large, caterpillarlike conduit carries oxygen to a mask over my nose and mouth. Little wires snake across my chest on their way to a heart monitor whose phosphorescent eyes shine behind my bed. A green, dinosaurish machine stands at one side of the bed, its shiny, pointed head turning and buzzing as different x-ray views of my body are taken. Silhouettes of nurses and attendants stand around me. A white-smocked surgeon runs moist hands over my abdomen and then, with a scalpel, cuts into the flesh between two ribs and inserts a tiny tube into the crevice. A thin stream of blood trickles out as I wheeze—two fractured ribs have punctured a lung. Somewhere inside me, life is pouring out an unseen fissure. My blood pressure does not rise, despite the repeated transfusions.

I stare out from the bed. I hurt everywhere but also feel dull and heavy. In a slow and labored way, I try to piece together what has happened. I know there was an accident, but it is difficult to believe that an accident could have led to the scene before my eyes.

Five miles away in one of those Yankee-owned chain restaurants with tinted wraparound windows and plastic banana stalks in the planter boxes, a swarthy, stubby, unkempt, chain-smoking man, with his tiny, meticulous wife and his gangling teenage son, waits in line for a seat in one of the gaily colored vinyl booths. At the man’s waist, right under the rumpled folds of his shirt, a pager buzzes; the other patrons stare at him as he moves out in front of them, hunting a pay phone. He dials, and a voice from Brackenridge tells him to come quickly. His plans for a fried-chicken dinner forgotten, he dispatches his son home with a friend and, with his wife, bolts through the plastic-veneered portals of the restaurant. Dr. Hiram M. is on his way to work.

Smooth, wide wooden doors are at the end of the hallway where I lie on a wheeled stretcher. Three men in faded green frocks stand near me, bouncing up and down on the balls of their feet, rustling the green crepe spats on their rubber-soled shoes. Their heads, covered with green crepe bonnets, turn right and left, looking for Dr. M. The sight of these men and the latticework of tubing around me are evidence enough: I know that I’m in danger of dying. The prospect is—well, aggravating. It is entirely too undecorous to die this way, without the grace of a good-bye to Marta—who, the men tell me, is not severely injured—and without the honor of dying on my feet, like the heroes who bite the dust in western movies. As they roll me toward the big doors, I find myself thinking, “Well, brother, this is it. It’s the end of the world for you.” The short future I imagine for myself—about three minutes long—is entirely unremarkable. I’m going to die stomach up on an operating table. I can’t even move to protest; a green-frocked man has already given me an injection that has brought on a paralysis of sorts.

There is a battery of lights above me on the operating table. Someone is speaking to me about anesthesia, and I see a hand move in front of my face, a hand raising a long, off-white tube above my eyes. The hand moves down and I feel the tube go between my lips. The hand shoves, and I gag as the tube strikes my throat. The hand pushes on the tube, and again I gag. The hand shoves again, and this time I feel the tube passing through, going down my windpipe. I lose consciousness; the tube is a conduit for anesthetic gas.

Dr. M. punctures the base of my chest and pulls his scalpel down the centerline of my abdomen. Waves of blood rush down my sides, cross the narrow margin of the table, and trickle to the floor. With rubber-gloved hands, the doctor spreads open the foot-long incision. Feeling and looking from top to bottom, he sees that my liver is bruised, but the spurts of blood do not originate there. They come from behind my stomach, from a ruptured spleen. Dr. M. clamps off the vessels leading to the spleen, then severs them and ties off their ends. He separates the organ from its moorings to the surrounding tissue and stands back to watch. Blood from a plastic pouch overhead is seeping into my veins, and within minutes my blood pressure rises. Dr. M. stitches up the autopsylike slash and then steps into the hallway to light a cigarette. He’s not at all sure that I’ll survive such massive injuries.

Jim Johns Mackie is upstairs at the police station, surrounded by tan walls, wire-mesh windows, booking-room clutter, and cops. As one officer rolls Mackie’s thumb across a white fingerprint card, a bigger cop stands at Mackie’s shoulder, urging him to take a Breathalyzer test. “I’ve already told you, I won’t do it until I talk to my lawyer,” Mackie barks.

A gray-haired officer who has been retired from the streets to booking-room duty leads Jim Johns to the row of wall phones in the hall. The prisoner punches out the number of an attorney and, as the phone rings, asks himself how he will explain that for the first time in his life, he is in jail, that this time he is not calling about an ordinary business affair. No one answers Jim Johns’s call. He requests a phone directory, finds the listing for another attorney, and dials again. This time a voice at the other end of the wire answers, hears him out, and advises him to remain firm, not to make any statements, not to take any tests. The old cop leads the prisoner away to a tan-painted cell, where a middle-aged beer-haller is already locked up for DWI himself. Jim Johns Mackie says little to his new acquaintance.

Moments after my arrival at the hospital, nurses summon my younger brother Gil from his house. He and his wife are given large, fire-engine-red polyethylene bags containing my effects and Marta’s. They are shown to a small, carpeted room with half a dozen padded chairs, a telephone, and a small wooden desk. A young woman in her thirties comes in, tells them she’s a social worker, and sits down behind the desk. She explains that I have several fractures and have lost a lot of blood, then tells them gently that though my surgery was successful, I may not live. She offers Gil the telephone. He dials our parents in Dumas, north of Amarillo. Mother answers.

“Could you get Dad to go downstairs to the phone?” he asks.

After a minute, Dad answers. “What’s going on, Gil buddy?”

“Well . . .” Gil knows he must choose his words. “Dick J. and Marta were in a motorcycle accident.”

Mother is silent. Ever since I bought the Harley, she’s been afraid news like this would come.

“Were they hurt bad?” Dad asks.

Gil says nothing.

“Gil, if you think we ought, we’ll fly down tomorrow,” Dad volunteers.

“You might catch the first flight out,” Gil blurts.

There is a short discussion about how the accident happened—Gil says he doesn’t know, but he and my parents suspect it was my fault—and then they hang up.

I have been carried to the intensive care ward, a brightly lit, hidden-away section of the hospital, where public entry is restricted, where each room has a long glass window looking onto a hallway with nurses standing at every door; where life-maintaining and life-monitoring machinery is at every bedside; and where, despite all these high-commitment measures, death is a common outcome. The room next to mine was vacated this afternoon by the corpse of a young man.

I have not been on the ward for more than an hour when a nurse, as she hangs a new blood pouch over my bed, notices a physical change that stems from one of my many internal injuries. There is a bulge at my crotch; pulling back the sheets, she sees that one testicle is swollen and darkened by blood. A urologist is paged. Once more, the men in green come for me. In the operating room, the urologist lowers a light and slits open my scrotum. The testicle inside is like an orange struck by a hammer, swollen as large, deformed and shattered. He excises it. Then the doctor ties off the cords and slips a tube into a separate incision on the scrotum. I am sewed up and wheeled back to intensive care again.

Marta is in the neurosurgery ward because she has a concussion. Nurses lift her from a stretcher into bed. She asks to use a bathroom. A nurse points her to it. Marta slides off the bed, takes a step, and collapses. Her right foot won’t support her; it is broken, though that has not been diagnosed yet. The nurses, supporting her between them, carry her to the bathroom, and before they can return her to bed, she has passed out again.

Jim Johns Mackie hears the guard calling his name. He glances at his wrist, but his watch is gone—the police have it sealed away in an envelope. Still, it seems to him that if the call indicates that his lawyer has come, his release cannot be delayed much longer. A cop with a brass key hollers out his name again, and the cell door clunks open. The prisoner collects his things and is shown to the outer hallway, where he is free.

After the lawyer has driven him home, Jim Johns lies back on his water bed and reminds himself that in a way, he is lucky. His parents are dead, he is unmarried: there is no one he has to explain to. He does not want to explain, he does not want to mention the incident to anyone, because there is something vague and discomforting about it, something that tells him that he has unwittingly done a great, perhaps irreparable wrong.

Jim Johns Mackie has been a careful man all his life. He has rarely taken too much to drink; he has kept his driving record clean, his insurance paid up. He has obeyed all the good adages, and his orderly character is evident even inside his house: there is a place for everything, and everything is in its place. He doesn’t understand how, after living with such discretion, a shameful incident like this one could befall him. There is just no justice to it.

Technicians and nurses pass by my bed like pilgrims before a shrine. Inhalation therapists connect a line from a green oxygen tank to the tube shoved down my throat during surgery; I breathe under the force of an electric pump. I am rewired to the heart monitor, and a tube through one nostril leads to my stomach. A surgeon cuts a second hole in my rib cage, inserting yet another tube. Narcotics are injected through my IV line. Bag after bag, transfusions continue—and the blood that runs in keeps trickling out through the tubes in my side.

A thin, fortyish, erect man glides toward my bed with slipper-soft steps. His unadorned navy blue tie is stiff, his white-on-white broadcloth shirt is as unwrinkled as parchment, and there is not a thread pulled on his vested business suit. In his long, sinuous hands he holds a big manila envelope bulging with x-rays, the blueprints of his profession. Monograms peek out and cuff links flash as he instructs the technicians in his train. While he watches, they swathe my right leg in cotton, then cover it with plastered gauze. At his direction, they strap a fleece-lined aluminum splint under my left thigh. With a carpenter’s drill, one of them bores a tiny hole into the flesh and through the bone just below the left knee. He inserts a shiny steel rod through the hole, then snaps a horseshoe-shaped chrome clamp to its protruding ends. The other technician knots a white nylon rope to the clamp and passes the rope through pulleys on the overhead frame of my bed. He ties its end to brass rings on plastic pouches filled with buckshot and lowers the weights toward the floor. As they go down, my leg is hoisted into the air, flexed at the knee. Dr. P. circles the bed, examining the work they have done and wondering if I will ever walk again. The x-rays in his hand tell him that the bones in my left hip and thigh are splintered too badly for mending with pins or screws. Traction will facilitate healing, but healing cannot be guaranteed when a half-dozen fractures must grow together again. Dr. P. does not relish the duty of explaining the probabilities to anyone. His back sags a little as he turns from my bed.

I do not rest well. The heart monitor blips behind me, and an oxygen pump hums. Something beeps when my air line clogs with saliva, and a buzzing comes from the telephone at the nurses’ desk outside my door. Technicians and attendants check my pulse, blood pressure, and temperature. They give me shots, change my blood and IV bags, inspect the level of urine in my catheter pouch. They cannot turn off the lights in my room, for they must see to perform their work.

Jim Johns Mackie does not sleep soundly either. A thump on the porch brings him to his feet. In his living room, he leafs through the newspaper, looking for a report of the accident. Nothing in the headlines. He pages through again, scanning every accident report. At the bottom of one of them he finds seven lines about our brief encounter. Jim Johns Mackie curls back on the couch, at ease: his name was not published.

By the time Mackie reads the notice, I have been victimized by what medical literature calls ICU (intensive care unit) syndrome, a complex, delusionary disorder. ICU syndrome is most frequently noted among patients who, like me, undergo surgery when their blood pressure is low, but it is common among others as well, in part because the timeless ambience of intensive care wards deprives the patient of his bearings on reality: daylight does not enter my room, there are no meals to keep time by, and the lights are never switched off. In fits of sleeplessness, I gaze out from my bed, unable to comprehend where I am.

Retrograde amnesia complicates my confusion. I do not remember the accident, nor do I recall having come home from Mexico some twelve hours before the crash. I had gone there as a consultant to an NBC crew filming a land seizure led by armed peasants. When I had left the country, the guerrillas were holding hostages in a hideout known to me but not to the Mexican government or the landlords it protects. As I look around my hospital room, I conclude that I have been wounded by some gun-happy federale or pistolero and I am in custody in a Mexican infirmary. The assumption is a relatively rational one, given my trauma-induced amnesia, and it is one I must struggle to maintain, because in moments of exhaustion I am overwhelmed by unintelligible subconscious intimations and can make no sense of my surroundings at all. Amnesia and the ICU syndrome undermine my sanity.

I am awakened by a voice at my side. Dad is speaking to me. I turn my head and see him in a herringbone suit, talking by telephone from a bookshelf-lined office in Nyack, New York. He says that Marta and I were in a motorcycle accident, but I shake my head to show I do not believe him. His accident tale, I suspect, was concocted to divert me from reporting on guerrillas again. I do not argue the point, however, nor do I attempt to explain. He must know the truth already, I believe, and any attempt to discuss it might provoke his CIA allies to punish me even more. Dad speaks for a minute longer, assuring me that I will be all right. Then he turns away and leaves. My dad is a tough-minded newspaperman in West Texas. For the first time in my life, I have seen tears in his eyes.

Two of my friends step in. One looks away from my bed, unable to bear the sight: my whole body is bloated with oxygen that is escaping from the lung punctures. In greeting, I raise a note pad—I cannot speak because the oxygen line blocks my throat—and pencil out a message: “How many segment-lives does a centipede have?” If either of them answers, I do not understand. Exhausted, I drop back into oblivion.

Shortly before noon, Jim Johns Mackie puts on his tie and makes an appearance in court. The proceedings are perfunctory. He is charged with driving while intoxicated, and a date is set for pleadings. Afterward, he has an important consultation with his attorneys. They tell him that he can probably beat the rap, and that if he can’t, the penalty will not be harsh: first-offense DWI cases in Texas are usually laid to rest with fines of less than $200 and probated one-week jail terms. If I die, however, Mackie could be indicted on felony charges.

The discussion unnerves him. He realizes that he has a stake in my welfare and a need to know about my medical status. He doesn’t like that, because he wants to forget the whole incident, to wash it all away—with an instant guilty plea, if necessary. But a guilty plea to DWI might hasten a lawsuit, jeopardize his license to drive, infuriate his insurer. Mackie is perplexed, but after a few minutes of reflection, he tells his lawyers that he will follow their lead, that he won’t confess to any charge without their counsel.

On the way home from his office, he stops at a convenience store to buy the evening newspaper, hoping to find news of my survival. He turns to the obituary page and his eyes move down the alphabetical list of the deceased. I am not mentioned there, or anywhere else in the paper. He telephones the intensive care ward. A nurse tells him that I am in critical condition but refuses to divulge more. Jim Johns Mackie wants to know if I am improving, but he cannot find out.

He had not eaten lunch, but now he downs a hastily prepared supper. It is no use; a few minutes afterward, he vomits it up. He turns on the television in his den and paces as he watches it, barely taking notice of the action on the screen. Before going to bed, for the first time in years, he looks upward in prayer. Jim Johns Mackie begs the Lord to forgive and heal.

The following evening, my brother Gil comes to visit me. I pencil out a question composed from my only trace of memory: “Boom! Why?” He pulls from his shirt pocket a clipping from that afternoon’s newspaper. The two-column headline reads: TEXAS MONTHLY WRITER HURT IN CAR-CYCLE CRASH. I read over the first paragraph of the story, then scrawl out a message: “Trick!” I may remember a boom, but I do not recall any cycle wreck. Maybe the boom was the sound of the gun that shot me. In my puzzlement I am certain of only one thing. There is a conspiracy to silence reports of the Mexican land invasions, and the accident story is part of the scheme.

Jim Johns Mackie reads the same notice and is skeptical too. It has been two days since the accident; its newsworthiness has passed. He suspects that reporters at the Austin American-Statesman, on learning that a journalist was injured, decided to revamp the story into a tale calculated to win sympathy for their profession.

Two days later, on Thursday, Mother comes to my room with Marta. My wife is thinner now; she is in a wheelchair, one side of her face is swollen and blue, a cast is on one leg, and she mutters unintelligibly. She does not seem to understand the notes I write her. She has been tortured, I believe. Seeing her is a warning: I must escape, before I am tortured too.

I have already written notes a dozen times, in English and Spanish, offering bribes to nurses in exchange for liberty. The effort has produced nothing except an acquaintance with bilingual hospital personnel. It is by now clear to me that nobody is going to aid my escape. When Marta and Mother leave, I set about arranging it on my own. I extract the long tube that carries digestive fluids from my stomach up through my nose and down to the pump at bedside. I yank out my catheter and strip the tape off my IV needle—and nurses pounce on me. Attendants come to help them subdue me. They reinsert the noxious tubes and tie my wrists to the railings of my bed. My head can move freely, though. I chomp through my respirator hose. There is a loud beeping, and I lose consciousness.

While I am out, a surgeon cuts a slit just below my voice box. He installs a small plastic tube in the incision and connects another oxygen hose to it. Afterward, nurses tell me that the tube is a breathing device called a trache. I do not believe them, for, after all, they still have me tied to the railings. I believe the trache is actually a tiny radio speaker, installed to broadcast messages from Mario Cantú, the mercurial San Antonio revolutionary and consort of guerrillas. Every time Cantú speaks, he denounces someone for betraying the Mexican revolution, and his voice is transmitted through my speaker as a cough. The history of the Mexican revolution is fraught with treachery, and there are thousands of men, living and dead, who can be denounced; Cantú, it seems, is intent on naming them all through me. Every time he speaks, the nurses come running. They disconnect the oxygen line, and I cough up yellow-green slime, sometimes streaked red-brown with blood. After the denunciations, I breathe easier.

Jim Johns Mackie thinks he has been denounced, though not by Cantú. He thinks that journalists are out to get him. Tuesday morning—more than nine days after the accident—he finds a notice in the newspaper, a two-column item captioned “Correction.” The story points out that his name was erroneously shortened to Jim Johns in previous reports. He believes the erratum notice could only reflect a desire, not to protect the innocent, but to punish the guilty.

He thinks the story is not fair at all. It will inform his business clients and social peers that he has had a run-in with the law. It will bring the public in on what he considers an essentially private event. Jim Johns Mackie has already had enough; even casual associates have commented on the signs of strain. His face has turned expressionless, he has become inarticulate even in ordinary conversation, and he has stopped making the sardonic current-events quips that two weeks before were repeated from desk to desk by admirers in his office building. The financial cost of it all is nothing to scoff at, either. The men at the garage and body shop say it will cost him more than $1500 to repair his pickup, and there will be lawyers’ fees and probably a hike in his insurance rates.

The nurses unbind my hands only when I have visitors and when they want to communicate with me. This practice deepens my distrust of visitors and hardens my belief that I am indeed a political prisoner. Marta and Mother visit again, and I note that Marta now wears street clothes, not a hospital robe, that she is no longer confined to a wheelchair but limps around with a shoe on one foot, a cast on the other. Apparently, she has been freed. When she urges me to cooperate with my nurses, I am convinced that she has signed some statement indicting Cantú.

Gil comes to visit the following day. In a calm and reasoned way, he again explains that I am not in Mexico, and he offers a new document to support the contention. It is a list of the names of people who have given blood for me.

Several times that day and the next, I scrutinize the roster. There are fifty names, some of them unknown to me. Other names I recall from the antiwar movement of the sixties, and still others I recognize as those of fellow writers and journalists. The CIA, I know, could be aware of my acquaintance with some of the former protesters. But it could not have persuaded writers and editors—generally a skeptical lot—to make any sacrifice for me, or to help put over any hoax. I trust those names and am persuaded that I am not in Mexico, that I have not been shot.

New delusions quickly replace the old ones. Brackenridge Hospital, I gather, is a unique institution that evolved from a collective of university students who are health activists and whose uniform is the green frock. These illusions are eclipsed by a new pain. My liver, inflamed by too many transfusions, quits working. It will not detoxify painkillers and sedatives. My skin and even my eyeballs turn yellow, and my whole body seethes with agony so intense that again I cannot sleep. Streaks of pain show me injuries I had not noticed before. My left arm, zebra-striped with bruises, is offended by every touch. When I move, a raspy pain barks from my rib cage and there is a stabbing sensation in my shoulder, where a collarbone and a scapula are broken. Brute, unyielding pain convinces me that I am dying, and that dying is the best way out.

For two or three days the pain never stops. I want to die, for the pain is insufferable and, apparently, beyond recall or control. I write a note to one of my nurses: “Can you cancel me out, replace me, or do anything?” Though I am not Catholic, I ask for last rites, and when I still do not die, I decide that somehow I’ve got to find a way to kill myself. Marta comes to my side, leans over, and embraces my skull, the only unencumbered patch on my body. My suicide fantasies are extinguished by the realization that if I die, she will be left alone. I write her a note: “I want to die, but I can’t, because that would make unhappy you,” and for the first time in nearly five years, I cry.

By morning the pain has eased. I awaken after a nap with that ready-for-action feeling that tells me I’ve got an answer in my head. I’ve cracked the riddle, I know who I am, I have it all figured out. Craning my neck, madly blinking my eyes, moving my soundless lips, I beg the nurses to untie me, then I pick up a pen and scribble out my formula. It is not as terse as what Descartes wrote, but it is perceptive enough to give hope: “Yes, I am me! I am the one who was on the Harley. Overnight, I became transubstantiated. They were talking English, not Kaffir. Pure identity, Jesus.”

The ICU syndrome won’t let go of its hold, however. Thinking for a while in Spanish, I conclude that I am an invalid, un inválido, and I observe that the word connotes worthlessness. A man should work, and if he cannot work he is not valid, he has no financial worth. I don’t like to think of myself that way. I write out a note to one of my nurses, telling her that I feel “like a combine rusting in a wheat field.” She sympathizes, and I follow with a second note: “When will you take me off the layabout list here? I am unemployed as writer by wreck. Will work as nurse until cured.”

My request is granted. An attendant rips the wires off my chest and carts a machine away. Then he comes back with a green-frocked partner; and I feel the casters of my bed roll. The attendants push me down a long, chilly hallway, with plate-glass windows on the sides. I turn my head and look out. There is darkness and the silhouette of a tall black building, nothing more. The sheets over my naked body give me no protection against the cold, and I conclude that if I am anywhere knowable, I must be in the frozen north, maybe in Ann Arbor, Michigan.

The attendants open a smooth wooden door and push my bed into a brightly lit little room. One of them hands me a white plastic device and tells me that if I need a nurse, I must push one of its black buttons. They reconnect my stomach pump, turn out the lights, and leave the room. I look around, but my curiosity fades. It is quiet and dark in this little refuge, and for the first time since life became so incomprehensible, I drop off into a deep, dead sleep.

Jim Johns Mackie is ready to rest for the first time in seventeen days. He has called the intensive care ward and has been told that I’ve been taken to the orthopedic floor, that I’m expected to live. He does not telephone the good news to anybody, because there is no one he wants to tell; nor does he pray tonight, for his prayers have been answered. He crawls onto his water bed and drops off to sleep.

The curtains over my window in the new room are open when I awake. Outside, seven stories below, are white stone buildings, and hills with lazy paved streets leading down to a ribbonlike river. The scene clears my head: I am looking down on Town Lake, in Austin. Something terrible has happened—there are tubes running all over my body—but at least I’m home. Turning my head away from the window, I shed silent, tracheotomized tears.

Within days Jim Johns Mackie puts aside the bitter protein solution he began taking after he noticed that his crisis was causing him to lose weight. He eats full meals again, without fear of throwing up. Before going to bed, he reads the New Yorker, as was his habit before, and he sleeps well. After a few days, Jim Johns Mackie even feels well enough to make a symbolic sacrifice: he donates a pint of blood to my account.

His optimism is soon diminished, however. His attorneys warn him that my father is seeking to have him indicted for aggravated assault, a felony. It is now too late to enter a guilty plea to the DWI charge, they say; no pleas will be accepted until the grand jury has decided to indict or defer. The juncture calls for audacious diplomacy. His attorney phones me to ask if I will receive Mackie in my room.

My condition has improved. One by one, the lifelines running to my body have been pulled. The trache is gone, and I speak now. There are no more barbiturate injections. My head is clear. I know where I am and how I got here. I know that another living, human individual—a statutory equal—put me here. It does not matter whether he intended me harm or not; I’ve got to pay the price. In daydreams, I cultivate a scenario of revenge. I imagine shooting him with a shotgun, not to kill but to wound.

The fantasy has salutary effects. Each time I picture myself standing over my crippled prey, it is as if I can feel my own shackled, shrinking muscles move. Revenge restores in imagination that active self that circumstances have taken away.

The morning before the day of Mackie’s visit, technicians wheel me downstairs. They disconnect the rigging that holds me in traction. The orthopedist, still in a speckless suit and a white-on-white broadcloth shirt, picks up his carpenter’s drill, hooks it to the rod in my leg, and twists. I wince and curse. When the rod has been extracted, they lift me over to a rack made of steel tubing, which supports all my limbs about two feet from the floor. The orthopedist and his assistant begin wrapping my feet with warm, wet gauze soaked in plaster of paris. They keep wrapping, up to my waist, over my stomach and rib cage, up to the nipples on my chest. One of them places a length of half-inch wooden doweling between my legs, just above the knee, and tacks it down with wads of plastered gauze. I can no longer move my legs or bend at the waist. I am imprisoned in a shell, stuck down, flattened out, immobile, like the cockroach in Kafka’s Metamorphosis. Now, more than ever, I am Jim Johns Mackie’s victim. Only my imagined revenge gives me the steeliness to stifle my tears.

The next day, on the hour of the appointed visit, Mother and Marta show up, both fearing that I will lash out at my well-wisher.

Jim Johns Mackie arrives with the expectation that after a few minutes of polite conversation, I will promise to ask prosecutors to drop the charges against him.

“I am sorry about the accident,” he tells me, bowing his head a little, staring down at his loafers, dropping his hands to his sides.

“What accident?” I bellow.

Mother removes her eyeglasses and looks down at her lap; she’s seen my ugliness before.

“Accident, hell. You maimed me, that’s what.”

My guest wrinkles his tanned brow, trying to make out my meaning. In a little voice, he tells me again that he is sorry and mentions the pint of blood he donated last week. He moves his shoulders around, creating wrinkles in his polished cotton shirt. Its cuffs stick out under the sleeves of his fleece-lined corduroy jacket, a reminder that outdoors, winter has come to Austin. Nervously, Mackie moves his feet from side to side, his arms clasped around his rib cage.

I ask him about his liability coverage.

He tells me that he is well insured. His policy will pay off my costs—and then some.

“So what? You want me to drop charges?” I grunt.

Mackie stares at the floor again, muttering something like “That’s kinda what I hoped.”

I sit up as straight as I can.

“My dad is the one who wants those charges, and I’m not going to bother him. But I’ll tell you what . . .” I pause until he looks squarely at me. “I’ll ask him to drop charges on one condition.”

Mackie is attentive now.

“You get on a motorcycle, and let me get in your Toyota, and we’ll meet the same way at the same place.”

Mackie steps back. “This man’s crazy,” he tells himself. Politely, he begs his way out of the room and goes off wondering why his attorneys set up this encounter with me, a madman.

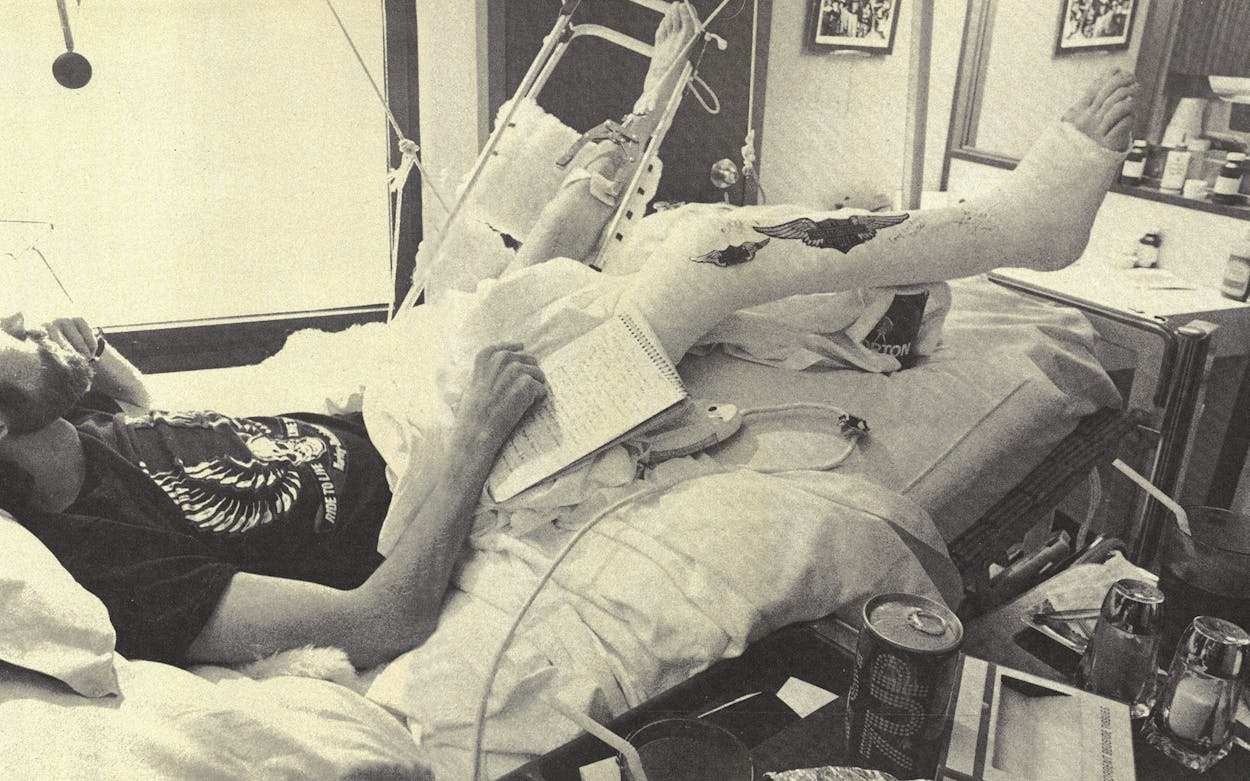

Two months after the accident and two weeks before a bleak Christmas, an ambulance hauls my plastered body home. For the next sixty days, I lie face up in my study, comforted by Marta, nurtured by my friend Carlos. Acquaintances and friends encircle my bed; even the Fort Worth Bandidos come down to visit. With encouragement from my editors, I begin writing again, this time on a typewriter suspended over my bed. Productivity and my friends’ respect restore my self-satisfaction, though things are still rough. Each day there are bouts with constipation, and vomiting sometimes comes in volleys.

In mid-January, after nearly ten days of bargaining with the prosecutor’s office, Jim Johns Mackie appears in district court and pleads no contest to aggravated assault. He is sentenced to five years on probation. Mackie thinks the penalty is a heavy one, given in deference to my profession. At least, he tells himself, serving out the sentence will not be as stressful as going through an extended trial.

The probated prison term, Mackie learns, can be completely discharged by twenty months of good behavior. After an initial period of lengthy interviews, his monthly reportings will be reduced to contacts lasting less than five minutes. The most distasteful feature of his probation plan is the requirement that he attend half a dozen group therapy sessions for alcoholics.

Three days after his sentencing, Jim Johns Mackie accepts an invitation from married friends to watch the Dallas Cowboys in televised gridiron combat again. It has been months since he has relaxed in this Sunday way, as a man ought to, happy and without preoccupations. More than anything, Jim Johns Mackie is happy that he has resolved his legal hassles before this, a Super Bowl day.

He does not know it, but he could have beaten the aggravated assault charge. The Texas statute on felony assault lists reckless driving as a violation, but appeals courts have ruled that drunk driving, because it lacks the element of intentionality, cannot be punished as recklessness can. As our judges have seen it, hot-rodders intentionally subject others to risk, but a drunk behind the wheel means no harm; speeders are feloniously liable for injury to others, drunks are not. Had Jim Johns Mackie fought his case through the courts, he could have been convicted of misdemeanor DWI only.

In late February, Mom and Dad fly down again and Marta takes off from her job to accompany me to the casting room at Brackenridge. We believe that this morning, when my body cast is cut away, I’ll walk again. Mother brings my shoes and waits with Dad in the hallway. Using electric saws with shimmering, silver-dollar-size blades, technicians buzz lines down the plaster, then strip it off. My skin is pale, thick, caked, dry, and flaky; my legs, mere underpinnings for atrophy. The business-suited orthopedist comes in and orders x-rays, but he already knows—he’s always known—that I won’t walk today, if ever. The x-rays also confirm something that for one reason or another has not been diagnosed before, but that constant pain has called to my attention: a bone in my right hand was broken in the wreck. The orthopedist orders me wheeled upstairs for admission, Marta collapses in tears, Mom and Dad go home disheartened.

Physical therapists bathe me and bend my knees each day. Their work gives me hope, for unlike other treatments, it is based on my strength, however residual, and not upon weakness and injury. After I have been in their care for ten days, a long plaster casing with steel hinges at the knee is wrapped around my left leg. Simpler, shorter casts go on the right leg and hand. I’m discharged in a wheelchair, with orders to buy crutches. But within two weeks, and against the orthopedist’s advice, I’m goose-stepping around like Frankenstein’s monster. Ultimately, my heedlessness takes its toll: searing sores develop on the parts of my legs that rub roughest against their plaster shells. The pain is intense, and when I return to the casting room in May, it has kept me sleepless for two days. This time the casts are cut away for good. A metal brace is fitted to one leg, and I begin learning to walk again.

Each metamorphosis brings on a change in mentality. I was generally content while in the body cast, for it provided a clear choice: acceptance or despair. The leg casts are more difficult to cope with, for I never know how far I can walk or when I will tumble to the ground. Each time I experience difficulties, I extend a form of psychic credit to myself. I tell myself that today I cannot manage as before, but that someday I will be able to pay back all my suffering in the token of revenge. As my cramps and stings and muscle pangs fade away, so does the promissory note to violence.

My recuperation is not finished. Today, fifteen months later, there is still a cast on my hand. There are some abilities, like running and jumping, that I’m not expected to regain. Each morning when I awaken, my left hip is stiff, and only with difficulty do I descend the stairs to my study. When it is cold outdoors, the hip joint hurts and I limp a bit; doctors say that when I am forty, arthritis will set in. I wear a wing-shaped medallion around my neck not for luck or sentimental reasons but to cover the tracheotomy scar. Lying in a body cast a year ago, I daydreamed of dancing and promised to take lessons when I walked again. Today, I do not have the range of motion needed for dancing.

Marta’s health is unsteady too. For several months after the accident, she was subject to extremes of anger and fear. There were gaps in her memory—she could not, for example, find her way through the once familiar streets of Austin—and she was often confused by tasks that were routine before. Today, there is a thick callus the size of a half-dollar on the sole of her injured foot. Her doctors say the callus is caused by the dysfunction of the two toes that now point upward at their ends. More aggravating, one side of her face, from the cheekbone to the upper lip, is nearly insensate. She cannot fully control her speech, though the difficulty is rarely obvious to strangers. When she recently had dental work in the affected area, pain shot all the way up to her eye socket, where the pinched nerves lie.

Marta is fearful, as never before, when I leave home to work outside Austin; she believes that I may very well die on any assignment. She and my mother suffered most from the wreck, and their apprehensions continue day after day. My own psychological response was different. I developed what blue-collar Texans call “an attitude.” I am not as tolerant or patient as before. Instead, I am aggressive, adamant, and touchy about all relationships. I am determined to get what I want, now, before my course is again interrupted.

Doctors, family members, and friends urge me to remember that I’m lucky to have lived through the wreck: 29 pints of blood and plasma were given me, and all told, eleven bones were broken: a tibia, a fibia, a femur, a hip socket, three ribs, a shoulder blade, a collarbone, the scaphoid bone in my hand, and a bone in my foot whose name and precise location I’ve never learned, since it was healed before I knew that it had been fractured along with the others. My own memory recalls the points at which I believed I was dying, but without the ominous sense of impending loss, without the specter of grief, that Marta, Mother, and others endured. At each apparition of death, my own thoughts and sentiments were entirely commonplace.

If the accident could have taught me lessons to live by, I failed to learn anything new or unique. If I faced death stonily, it was only because I was too weak and exhausted to feel remorse or fear, or because, at the moment and beforehand, I believed that life had already given me a good deal. At 32, I had seen as much adventure as anyone could want and I had lived, as I still do, according to my own lights, not by the opinions of social seers, the masses, or the usual worthy authorities. The lesson I wish I’d learned from the wreck—how to avoid drunks on the highway—can’t be taught at all. If there is anything in the category of universal wisdom that I can offer as fruit of the experience, it is this: insurance is good for the victim and the culpable party alike.

After his insurer had paid off and I’d signed a waiver of future claims, Jim Johns Mackie admitted me to his house, and for two hours we talked about his recollections of the crash, about his legal standing and my prognosis. During the writing of this article, I telephoned him a dozen times to insure the accuracy of my report. At each contact, we both effused politeness.

But I have not pardoned Jim Johns Mackie, nor do I think I can. I have noted a kindred attitude among veterans who were wounded in Viet Nam. Ten years and a thousand political critiques later, few of them have forgiven anybody—on either side of the firing line. It matters little to the veteran whether he was wounded in a mismanaged war for democracy or in a war for imperialism; neither does it matter to me that I was injured by a man who meant no harm. What matters are the injuries. Injuries are more enduring and more material than moral or political issues. Time and reflection do not restore maimed bodies, and medical science can work only approximations. Each time my legs hurt or attention is called to the marks of my surgery, I am reminded that those are the signatures of another man’s caprice. Men who were wounded in Viet Nam feel the same and—with every right—feel it more strongly. Unnecessary suffering is the most difficult to forgive.

The bottom line in any true tale of trauma is simply this: all things considered, it would be a hell of a lot better if it didn’t happen, ever.

Even Jim Johns Mackie tells me that.

*Not their real names.

- More About:

- Health

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Austin