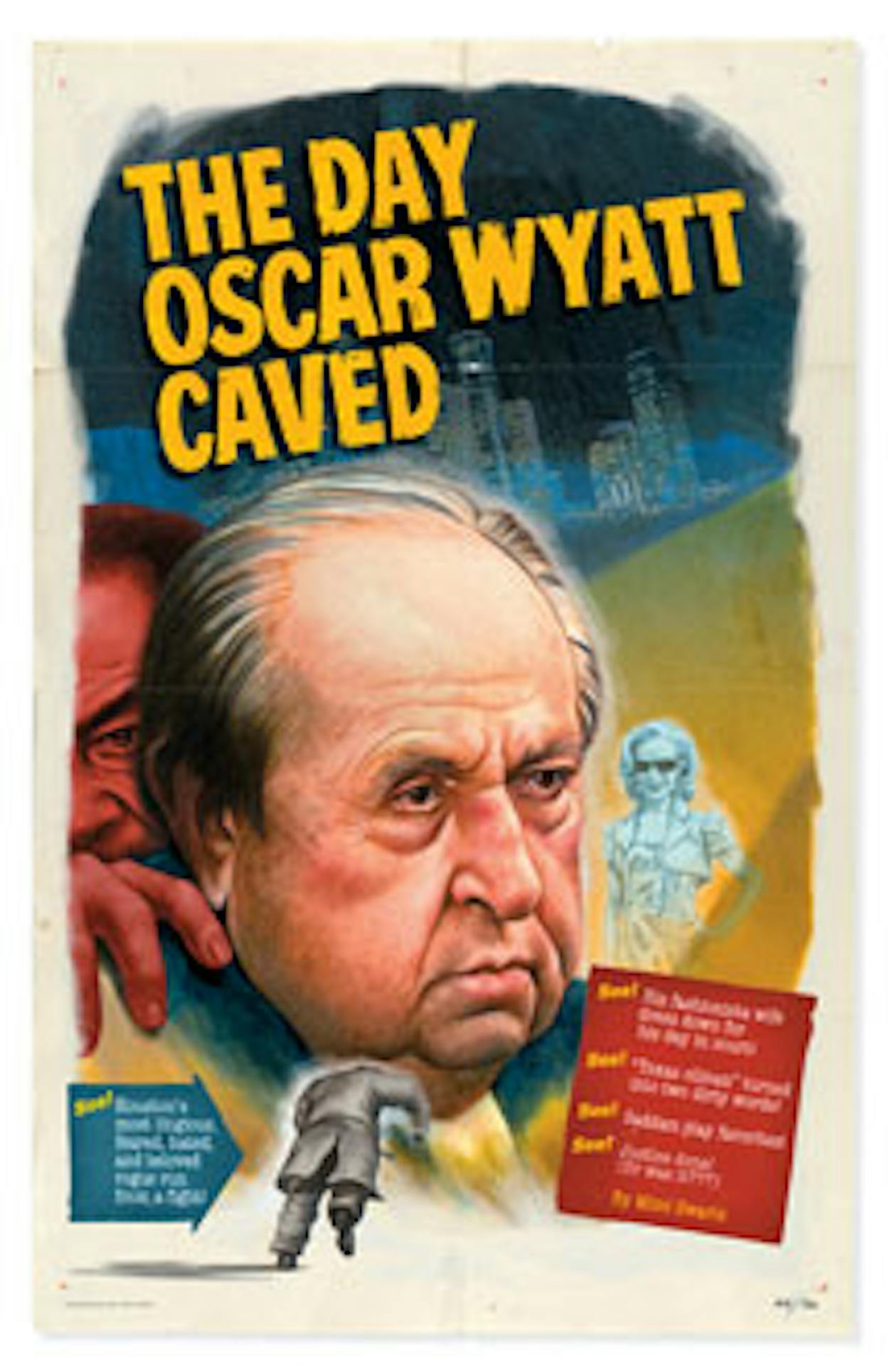

For Houston it was a real “say it ain’t so” moment. Oscar S. Wyatt Jr., that archetype of Texas archetypes, for decades the city’s orneriest, wiliest, most litigious, most feared, most hated, and most beloved son of a bitch, stood before a judge and pronounced upon himself the word few had ever successfully attached to his name: “guilty.” Within minutes—once the Houston Chronicle e-mail alerts started reaching influential BlackBerrys late in the morning of October 1—the news seemed to be all over town, along with the concurrent reactions. Oscar (and it’s always been “Oscar,” whether you really knew him or not) shouldn’t have copped. Oscar could have beat it. Or simply: Oscar, wow. Whatever was said, the undercurrent of disbelief ran fast and furious. Oscar Wyatt—a man who, in 83 years, had never backed away from a fight—had caved.

The trial, in a sunny New York courtroom with paneled walls and a view of the Hudson River, had been going on for nearly four weeks by then, but it hadn’t been looking particularly good for the infamous Texas oilman from the beginning. For those in need of background: Two years ago he was indicted on five criminal counts, including wire fraud, in connection with what came to be known as the Oil-for-Food scandal. As retaliation for Saddam Hussein’s 1990 invasion of Kuwait, the United Nations imposed economic sanctions on Iraq, which caused undue suffering among the Iraqi people and great consternation for the West, which could no longer buy Iraq’s oil. In 1996 the U.N. came up with a compromise, in which Iraqi oil profits were put into a U.N. escrow account to be used for humanitarian purposes (medicine, food, etc.). The U.N. allowed Saddam to pick his customers, and he selected a handful of his most loyal, including Oscar. Yet four years later, Saddam decided he wasn’t making enough of a profit on the price set by the U.N., so he started demanding “surcharges,” or bribes, from his customers. Many turned to middlemen, keeping themselves out of trouble, but, according to prosecutors, Oscar instead set up front companies overseas that paid the bribes and continued to do business with the Iraqis—illegally.

On October 21, 2005, when the feds pulled up to Oscar’s new mini-mansion on quiet, leafy Meadow Lake Lane, they manhandled him in such a way that he threw out his shoulder and required examination by that world-famous orthopedist Michael DeBakey. (Subsequent photos showed Oscar, scowling, in a sling.) Leading up to the trial, his defense appeared informally two-pronged: He didn’t violate the sanctions, and, besides, everyone else was doing it. (In fact, a commission that investigated the scandal—headed by former Federal Reserve Board chairman Paul Volcker—concluded that about half of the 4,500 companies in the Oil-for-Food Program paid a total of $1.8 billion in kickbacks and illicit surcharges to Saddam’s regime.) The defense also floated the issue of “vindictive prosecution”—that is, the Bush administration singling out its old nemesis in both the oil patch and politics, Oscar Wyatt, for punishment but leaving other possible violators of the sanctions alone. Prosecutors, in turn, amassed a daunting paper trail and rewarded a few former Iraqi petrocrats with help in obtaining U.S. green cards—as long as they agreed to testify against sanction breakers like Oscar. By the time jury selection rolled around, it looked as if the prosecution essentially intended to try him for treason, which infuriated Oscar’s cousin and defense team member, former state senator Carl Parker. “Those bastards are so intent on making Wyatt a traitor,” he told me, as voir dire was about to begin. “He’s done more for this country than all the asshole lawyers put together.”

Clearly this was going to be nothing like the trial of Enron bosses Ken Lay and Jeff Skilling, another defining moment in the life of Houston. By the time those two faced a judge and jury, they had no reservoir of goodwill in court or in the community; they were just two fairly typical corporate chiefs who had been looking out for themselves as their company went down the tubes. But Oscar was different: Born into poverty in Beaumont, abandoned by an alcoholic father, raised by a devoted single mom in Navasota, he grew up to become a World War II combat pilot and, later, the billionaire owner of Coastal Corporation, a company he started all by his lonesome. And yes, he’d sued and countersued, and he’d shrugged off (minor) guilty pleas in the past. In the seventies, he’d curtailed gas supplies to Austin, Corpus Christi, and San Antonio during one of the coldest winters on record. After Congressman Henry B. Gonzalez suggested in 1984 that “a more corrupt nor least trustworthy person could hardly be imagined,” Oscar retorted that Gonzalez was “a mental incompetent and has been for years.” In a brilliant reputation overhaul in 1990, Oscar flew to Iraq with former Texas governor John Connally and liberated U.S. hostages held by Saddam. When a Middle Eastern official claimed that “white slaves from America would liberate Kuwait,” Oscar took on George H. W. Bush’s war in a public forum, arguing, “I have five sons, and I damned sure don’t want any of them, or any of your sons, to be the white slaves of an Arab monarch.” Then, in 1991, in a continuation of an old feud, Oscar put Lynn’s son Douglas up to suing her brother, Robert Sakowitz, for $8.5 million, accusing him of self-dealing and plundering the family’s Sakowitz department store chain. Robert won, but as Oscar told me recently, chuckling, “You see how well he’s done since then.”

Oscar seemed to be easing offstage in January 2001, when he sold Coastal to El Paso Energy Corporation and announced his retirement. But then, surprising almost no one, he subsequently decided he didn’t like how El Paso was running things, launched an unsuccessful proxy fight, and started a new company for himself. No wonder he and his fourth wife, Lynn—a fixture of the fashion press, a best-dressed hall of famer, and, until recently, the hostess of lavish birthday parties at their rented Mediterranean villa—were known as Beauty and the Beast.

In other words, Oscar Wyatt was the personification of a rogue, and loving and hating him was one of the rare consistencies of life in Houston. So when his trial began in September, no one back home could imagine that he could be found guilty and sentenced to as many as 74 years in a federal pen, even though that possibility was mentioned in myriad Chronicle stories. The joy would be in watching him wriggle out of this jam, just as he’d wriggled out of so many others. Any other outcome was, simply, inconceivable.

Sitting in a jury room in Lower Manhattan, it was a lot easier to think that Oscar’s luck might finally have run out. (Uptown, it was coming up on Fashion Week, but that seemed irrelevant. Even Lynn Wyatt was dressed down, previewing a subdued if well-fitting black suit that would hence make several appearances with contrasting silk blouses.) Houston seemed far, far away as Judge Denny Chin, a Clinton appointee with a reputation for fairness and a pained, exacting demeanor, began interviewing jurors. (The trial was set here because of jurisdictional matters, including criminal acts supposedly committed in the Southern District of New York.)

Here, then, was the jury of Oscar’s peers: people who read the New York Times, the Daily News, and the New York Post; people who perused O magazine and watched Wheel of Fortune, Grey’s Anatomy, and the History Channel; people willing to swear that, although Saddam would be a major player in the trial, they could keep their feelings about our current folly in Iraq out of their verdict-rendering duties. “This is not a trial about the war,” Chin stressed, frequently admonishing jurors to “keep an open mind.” Even though his voice was soft and his frown gentle, you got the sense that he knew how hard that was going to be.

The Wyatt family was there en masse those first few days. The sons Lynn had had with Oscar seemed as different from each other as from the rest of the family: Trey was brooding and beefy, with a Caesar-ish trim to his black, black hair, while Brad, currently working for the society mortuary in Houston, was sweet and solicitous. The two handsome, perfectly tailored sons Lynn had had with her first husband, Robert Lipman, wore an air of privilege like a good cologne. The shoes and handbags chosen by Lynn and her equally well-accessorized daughter-in-law gave them away; no jury consultant was ever going to disguise them as members of the middle or even upper middle class. Lynn may have passed seventy, but her hair was still a glistening gold, and her figure was as trim as, if not trimmer than, a teenager’s. She straightened her husband’s jacket when it bunched and tried otherwise to be a good hostess to all, which was what the job called for.

The rest of Oscar’s team was rougher around the edges and, therefore, more reflective of the defendant. His Manhattan attorney, Gerald Shargel, a tall, full-bearded, fastidiously elegant man, describes on his Web site his experience as “house counsel to the Mob.” (Shargel, who had been John Gotti’s lawyer, was celebrated in a New Yorker profile for his brilliance, quick wit, and enthusiastic defense of the indisputably guilty.) Along with another lawyer—a Richard Lewis look-alike named Henry Mazurek—and a jury expert, Josh Dubin, there was the Texas contingent: Parker, a rotund, hilarious quipster in an out-of-season sports jacket, who looked as though he should have been playing the role of Willie Stark instead of Oscar Wyatt’s attorney, and Tony Canales—yes, the Tony Canales who, before becoming a criminal defense attorney, had prosecuted Oscar in the seventies, when several cities in South Texas claimed that Coastal had mercilessly overcharged them. Silver-haired and bespectacled now, Canales has a voice that still crackles like a rifle shot. (Parker and Canales traded good-humored barbs about each other’s weight and ethnicity in the elevator, which probably confirmed the worst suspicions of their fellow passengers.)

And there was Oscar himself. He cleaned up nicely in natty pinstripes and combed-back hair, and his color was good—better than Ken Lay’s during his trial—even though he ostensibly wasn’t feeling well and made a few quick exits the first day, avoiding the press and bolting at one point from the jury room. In fact, he looked less like a man under the weather than one who had other places to be and wanted to hurry this tiresome process along. Oscar is not a tall man, but he moves like a powerful one. He lumbers like a battered old lion, his sagging jowls and age spots paying obeisance to his age but his bright, shrewd eyes giving the lie to it. He stood as required but just graced the jury with a casual nod when the judge introduced him.

In contrast to the defense team, the prosecutors appeared to have been sent from central casting. They were youthful thirtysomethings with prosecutorial names (Edward O’Callaghan, for instance), prosecutorial haircuts (short, recent), and prosecutorial clothes (white shirts, dark suits, off-the-rack). In other words, they were killers.

The 150 or so potential jurors studied the scene with growing interest, until Chin revealed the awful truth: The trial could last four to six weeks. There followed the rush of get-out-of-jury-duty excuses, which were, frankly, a little surprising. (Saddam Hussein, a Texas oilman, the U.N., and big-time bribery? Wasn’t this a no-brainer?) Ultimately, the departures left the defense and the prosecution with a jury that looked remarkably like those found in Harris County civil courts: mostly lower income and mostly black. In contrast to Harris County, however, many here had college degrees and were far more liberal.

It wasn’t known at the time, but this jury of five men and seven women was worrisome to both sides. A poor minority jury would be more suspicious of the government’s actions than a wealthy white one, but they might also be disgusted by a man playing footsie with Saddam, no matter when it happened. The worry factor increased when, on the first day of trial, a white college student—a young man who was probably a prosecution pick—failed to show up on time and was replaced by an older white man, a “retired artist” who favored straw hats and denim shorts. Right there, you sensed much debating to come in the deliberation room.

As with all trials, a lot of legwork had been done before opening statements began, most of which had to do with keeping the troublesome aspects of Oscar’s personality from the jury. The defense, for instance, persuaded Chin not to admit into evidence a taped conversation in which Oscar referred to a female attorney this way: “I don’t know who this Regina Speed-Bost is, but I’ll bet she’s a nigger girl . . . Ain’t nothing wrong with being a nigger as long as it ain’t you.” And there were problems with certain exhibits: for instance, a poster the prosecution intended to use as a visual aid, purported to be a chart of illegal oil sales, featuring a photo of Oscar with arrows linking him to Saddam. The judge sustained the defense’s objection. “Put a flag [over his picture],” Chin said, waving his hand dismissively. “Don’t get too creative.” Oscar was less fortunate when Chin ruled that his address book—which had been lost or, maybe, accidentally “found” and photocopied in 2002 by U.S. Customs agents at Houston’s Bush Intercontinental Airport—was admissible, though with references to law enforcement sources who could help with possible “Nigerian scams” and the name of oil trader/coop flyer/Clinton pardonee Marc Rich blacked out. The judge also admitted Oscar’s Austrian passport, which listed his nationality as . . . Austrian, as well as excerpts from the diary of Mubdir Al-Khudhair, a former official with Iraq’s State Oil Marketing Organization (SOMO), who had spent a great deal of time with Oscar on his many visits to Baghdad.

Opening statements began on September 10, with a break for Rosh Hashanah (something that would never have happened in Harris County). The courtroom seemed forlornly empty for the trial of someone so famous back in Texas; certainly there were no overflow rooms, as there had been during the Enron trial, and there were plenty of seats behind the defendants and just beside the jury box. Aside from the Wyatt brood, there were a handful of jury consultants—dressed to look like lawyers or students—and a handful of reporters, the jolliest of which was a tall Brit from the Times of London, who, in contrast to the sartorial splendor of the Wyatt family, wore a loud checkered suit and a T-shirt with stains across his impressive belly. He had covered the February 2007 trial of South Korean businessman Tongsun Park, who became the first person convicted in the Oil-for-Food scandal (of conspiracy, for which he was sentenced to five years in prison, fined $15,000, and forced to forfeit $1.2 million). The reporter cheerfully explained that there was great interest in Oscar’s trial in Britain because his stepson Steve Wyatt had played a role in the breakup of Sarah Ferguson and Prince Andrew.

So, early in the game, the Wyatts had stopped being real to the spectators in the courtroom. Once photographed as objects of admiration, they were now there to be studied, evaluated, judged, all within earshot. There were no supportive friends in the audience, no ladies who might have lunched with Lynn, no backslapping captains of industry—not even the curious, because Oscar really didn’t qualify as a curiosity in New York. The family seemed terribly alone, though they put a polite, well-mannered face on things and, except for Oscar himself, were pretty press-friendly. Still, it was hard to believe, watching Lynn sit wide-eyed and ramrod-straight a row or two behind the hunched backs of her husband and his lawyers, that it had come to this—that Oscar was, in fact, fighting for his life, that the couple’s glamorous, global, and compromised existence could, in fact, come to an ignominious end.

Just how ignominious was obvious when prosecutor Steve Miller, who looked like the kind of somber, diminutive grind Oscar might have bullied in high school, got up to speak. He called Oscar a “Texas oilman” multiple times, as if it were code for “greedy bastard.” He explained that, as of 1996, Iraqi oil was to be sold only through the U.N. program and that the money earned was to pay for basic necessities for the Iraqi people. But from 2001 to 2003, Saddam, in violation of the agreement, started demanding kickbacks from his customers, and those who wouldn’t pay didn’t get any oil. In the real world, this was called “the cost of doing business,” but this wasn’t the real world anymore.

“The Texas oilman promised he would make this illegal payment. That Texas oilman is sitting in the courtroom today. That Texas oilman,” Miller said, with a dramatic pause, “is Oscar Wyatt.” Saddam’s scheme worked, Miller continued, “because buyers like Oscar Wyatt agreed to help.” Hundreds of millions of dollars “went directly to the Hussein regime,” he said, because Oscar willingly broke the law—because Oscar made illegal payments through the creation of phony front companies, funneling the funds through banks in Cyprus and Jordan, in an effort to enrich himself by dealing with a state that sponsored terrorism. Miller vowed to play audio- and videotapes proving Oscar’s loyalty to Saddam. In other words—though he didn’t need to use these words—Oscar was a traitor.

Defense attorney Shargel’s story was, not surprisingly, the polar opposite of Miller’s. Where the prosecutor had been cerebral, Shargel was impassioned. He characterized his client as “born dirt-poor in Texas,” “a war hero who was twice wounded,” whose “heart was an American heart,” whose “patriotism was unwavering.” Oscar’s relationship with Saddam, Shargel noted, dated back to a time when Iraq was our friend. And Oscar had always been happy to share his vast reserves of oil knowledge and Middle Eastern expertise with a government agency that was never named in court and with presidents JFK, LBJ, Nixon, and Clinton; he just hit a few snags with 41 and 43. “He was no friend or admirer of those two other Texans,” Shargel said. In fact, in 1990 Oscar had begged the elder Bush not to take on Saddam, and when Saddam grabbed hostages trying to stave off a war, Oscar had to go in and rescue them himself. In the late 1990’s and early 2000’s, Oscar was just trying to head off another war—not, as prosecutors alleged, aid a dictator and profit mightily in the process. For six years, Shargel said, “Oscar Wyatt donated millions to bring food for the Iraqi people, including baby formula . . . all this in an effort to stop the insanity.” And during that time, Oscar bought no Iraqi oil, instead busying himself with helping protégés set up oil companies of their own. “Oscar wasn’t trying to make more money but to continue his role as dean emeritus of the oil business,” Shargel said, delivering a line that would be a real howler anywhere south of Tulsa.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” he thundered, “this case is about the U.S. at its hypocritical worst. This case should never have been brought. The government is trying to make a case out of no case and a way out of no way.” Oscar listened, slumped in his chair, looking at no one. It had to be the first time in his life that he’d accepted the role of victim.

After such a boffo opening, the first few witnesses were a terrible letdown. The prosecution began with a series of well-meaning U.N. types who had the thankless task of explaining how and why the sanctions were put in place, how the U.N. Security Council worked, how letters of credit were sent to the U.N. escrow account once oil was loaded onto a ship, and how, once the sanctions were in place and Saddam had made known his demand for surcharges, major customers—Exxon, Texaco, Chevron—were replaced by middlemen. “People with a phone and an office,” in the words of one witness. The jury grew both restive and glassy-eyed, as if they’d been promised The Bourne Ultimatum, or at least Syriana, and instead were getting a snoozer of a class in global trade.

Shargel was restive too, like a schnauzer on a short leash. What seemed to annoy him most was the portrayal of the Oil-for-Food Program as well run and effective. Without pushing very hard on cross-examination, he got witnesses to admit that the program couldn’t even meet the minimum requirements for helping ordinary Iraqis. There had been numerous resignations over corruption: Sixty-four billion dollars went into the program, yet no one seemed to know to this day where it went—including the Iraqis, who rationalized their need for surcharges by asserting that they received only about 54 percent of the funds, or about $34 billion. Did the U.N. ever stop intermediaries from buying and selling (that is, laundering) Iraqi oil? Did the ultimate end users (the big U.S. oil companies) ever stop buying Iraqi oil from middlemen? Any canceled contracts because of supposed illegality? The answer to Shargel’s questions was, inevitably, no.

In this way the polarities of the trial were established early on. The prosecution was armed with a set of facts that could be presented in witheringly damaging ways: Oscar had way more than a passing acquaintance with Saddam, for instance; Oscar’s company was the first to get a contract to buy and ship Iraqi oil once the Oil-for-Food Program was in place. There were plenty of “bad tapes” that many lawyers in Houston had already heard rumors about, along with some damning documents that made Oscar sound a lot more like a CEO trying to get around sanctions than, as Shargel would claim, a mentor trying to help old friends (in Switzerland, by the way) get their share of Iraqi oil. Yet Oscar’s story had drama, and Shargel was a fiery storyteller. Even when the prosecution tried to portray Oscar as a greedy, treasonous devil, the more logical interpretation—and the one the jury seemed to be warming to—was the one Texans long ago came to terms with: that the guy had always been a government of one, always ready for a showdown to get his way. Unhappy about high Iraqi oil prices set by the U.N.—the ones that made paying surcharges so onerous—Oscar was happy to go directly to the president of the Security Council, Ole Peter Colby. “If you let this matter stand, I will attempt a personal damage claim against the [U.N.] overseers,” he wrote. When no reductions were forthcoming, he dashed off a letter to Secretary-General Kofi Annan. “You will no doubt be solely responsible when the volume of oil begins to trickle out of Iraq,” he wrote in disgust, as if Annan were just another small-time regulator. And maybe he was; Annan and his son Kojo were also investigated by the Volcker commission, though no action was taken against them.

In fact, it became fairly obvious fairly early that the good guys were hard to find in this particular narrative. The Curse of Oil, which holds that an abundance of this resource tends to foster corruption, oppression, and ignorance, was once limited to oil-rich Third World countries and, well, Texas. Now it was spreading like a global plague.

About a week or so into the trial, the March of the Iraqis began. Reporters who had covered the Tongsun Park trial had awaited the prosecution’s presentation with glee, and it didn’t take long to see why: These men, most of whom had been intimately involved with the Oil-for-Food Program and, in particular, the sale or purchase of Iraqi oil, had star quality. They provided the jurors, who had most likely never traveled to or done business in the Middle East, with an intimate’s-eye view of the workings and the dangers of Saddam’s regime. An undercurrent of betrayal flowed through this testimony, compounded by the absence of people who might have spoken up for Oscar. Bayoil U.S.A. owner David Chalmers, whose father had been a partner of Oscar’s in happier times, had himself pleaded guilty in August to conspiracy to commit wire fraud. (On the other hand, he didn’t appear to testify as a prosecution witness.) Co-defendants Catalina del Socorro Miguel Fuentes and Mohammed Saidji, who had run the alleged front companies—Nafta, Mednafta, etc.— for Oscar, stayed put in Geneva, where they refused calls from reporters and were safe from extradition. Oscar probably preferred to live Nietzsche rather than read him, but listening to former colleagues sell him out, he might have reconsidered the philosopher’s warning that “whoever fights monsters should see to it that in the process he does not become a monster. And when you look long into an abyss, the abyss also looks into you.” At the least he might have reminded himself that if you lie down with dogs, you get up with fleas.

Hence the first Iraqi witness. Samir Vincent—“Sam” to some of his U.S. friends—was a white-haired, courtly Iraqi-born American citizen in a suit that wasn’t quite as good as Oscar’s. As a young man, he had left a well-connected life in Iraq for America, only to be lured back to help when Iraq was in crisis because of the sanctions. Vincent testified under a plea deal (he admitted acting as an unregistered agent of Iraq, among other things), and his story was magnificently cinematic: He told how, while living in Washington, D.C., he’d begun traveling to Iraq with Oscar in December 1990, working to free the American hostages and later to get the U.N. sanctions lifted. “The idea was to see if I could get my friends on board to prevail on Saddam for release,” he said. Vincent’s friends included high school buddy Nizar Hamdoon, who went on to become the Iraqi ambassador to the U.N.

This was exceptional cloak-and-dagger stuff. Vincent told of how he and Oscar and Connally flew first to Amman, Jordan, then headed to a VIP lounge, where they were handed tickets for an Iraqi Airways flight to Baghdad. Oscar’s arrival there was resonant of the Second Coming: Ramzi Salman, then the head of SOMO, wrapped him in a bear hug. “Obviously, he knew Oscar Wyatt very well,” Vincent said, deftly slipping nails in Oscar’s coffin. Once at the Al Rasheed Hotel—rooms were waiting for them—Vincent started working the phones, and eventually, Oscar and Connally were taken to the famous meeting with Saddam, who told them that their plane back to the U.S. “would not leave empty.”

What hadn’t struck anyone at the time—in Texas or elsewhere in America—was how totally loony this story was. Yes, their actions were brave and bold, but they also represented another classic example of the Oscar Way, a boundaryless variation on “if you want something done, do it yourself.” Why rely on your own government when you can sit down with a bloodthirsty dictator and iron things out? “Bush has pushed things to a quagmire,” Oscar told Saddam, his unmistakable, authoritative twang emanating from a tape played for the court. (Saddam was like Richard Nixon—big on secret recordings.) “He thinks if he pushes the Iraqis with brute force, they will succumb.” Oscar added that he had made it “very clear that Bush was playing with fire that will burn his hands up to the shoulder. This is no Panama. It won’t be a cakewalk. This is serious business. I know the Iraqi people very well.” Then, after displaying his prescience, Oscar turned to his true passion, which was making a deal. He had a refinery that he thought could be put to excellent use for Iraqi oil. Was Saddam interested?

According to Vincent, more trips to Baghdad followed—or rather, more flights to Jordan and eleven-hour drives in an SUV to Baghdad. “Why was it you didn’t fly right into Baghdad?” a prosecutor asked. “Oh, the no-fly zone,” Vincent replied casually. Oscar, according to Vincent, was then using his Austrian passport.

In the ensuing years, Oscar worked ceaselessly to ease the sanctions and then get a humanitarian aid program—like Oil-for-Food—in place, not just because he was a nice guy but because, without one, Iraqi oil wasn’t going to leave its ports and because he, Oscar, wanted to be the major, if not sole, buyer of it once the sanctions were lifted. (The West would look too cravenly oil-thirsty if it just chucked the sanctions; on the other hand, innocent people were dying. Oil-for-Food was the compromise.) To get a humanitarian program in place, Oscar tried to enlist the help of then—Red Cross head Elizabeth Dole (she stonewalled him) and former JFK speechwriter Ted Sorensen (his wife worked at the U.N.); Tongsun Park let Vincent know that he would be happy to help out for $10 million. Oscar, true to form, eventually took food and medicine to Iraq himself, along with a satellite telephone system he strapped to an airplane seat. (Apparently he’d gotten very tired of the bad reception. An earlier witness noted that when the U.N. called Iraq, the reception was terrible, but when Iraqi officials called the U.N., they could hear just fine. Still, providing a phone system violated federal law, the prosecution charged in its indictment.)

In the meantime, Vincent said, Oscar used some Canadian associates to buy the rights to acquire an oil field the Iraqis “had been saving for him.” Driving in another nail, Vincent told the jury what he had explained to his Iraqi associates: that “this was a company Oscar would like to use as a front.”

And life wasn’t any bed of roses with the Iraqis, despite their claims of fealty to Oscar. When, in 1995, they tried to call in one of his oil notes for $9 million, he was furious. That payment couldn’t be released until the sanctions were lifted, something Oscar believed the Iraqis knew good and well. “This group doesn’t learn their lesson,” he ranted, according to Vincent. “I told them over and over, I’m gonna pay that debt.” Meetings could be perilous: On April 1 of that year, Oscar and Vincent had to pass through two phony commando ambushes before arriving at one of Saddam’s palaces, then take an elevator to a particular floor, where the doors opened upon another set of large wooden doors attended by uniformed sentries who reminded Vincent of “papal guards.” Then, he testified, those doors opened, and “there was Saddam waiting with a battery of TV cameras and photographers.” April Fools’! That meeting turned out to be sort of a bore, as Saddam did most of the talking. He griped about the sanctions ad nauseam, noting that the Iraqis’ many friends had dwindled significantly since their imposition. “But you are one of them,” Saddam told Oscar.

“I appreciate the gesture, Mr. President,” Oscar replied. “I feel the same way about Iraq.”

Despite Oscar’s devotion, the Iraqis tried again to take advantage of him once the first Oil-for-Food shipments began, in December 1996. They presented him with a contract, all right—but for a measly two million barrels. Livid, he stormed out of the meeting, headed back to the Al Rasheed Hotel, and started packing. “They don’t appreciate all we’ve done for them,” Oscar supposedly growled to Vincent. “Let’s get out of here.” An oil minister tried to calm him by promising more later, but he was in no mood to negotiate. Oscar wanted what he was due on the spot. After much scurrying about, the Iraqis came back with a revised offer: eight million barrels. According to Vincent, Oscar’s response was “This is more like it.”

Oscar sat nearly immobile during Vincent’s testimony, though he grumbled about his former deputy’s account of the rescue. (“You’d think he did it all himself,” he told a reporter.) It seemed—again, not surprisingly—that the two had had a falling out over payment back in 1997. At one point, the Iraqis gave Vincent his own allocation of oil, which he, in turn, offered to sell to Oscar, who came up with a bid of 7 cents a barrel. Vincent had an offer from Chevron at 15 cents, and told Oscar so, adding that a Coastal executive had already okayed a higher price. “I don’t know a thing about it,” Oscar replied, and he then told Vincent to forget the deal completely and not to bother calling him again if he had oil to sell. But like so many others who have been in Oscar’s orbit, Vincent had trouble severing ties to him. After not speaking to him for years, he called Oscar upon hearing he’d had a heart attack.

“My mother’s ninety-four,” Oscar told him. “I’m not going anywhere.”

Along with the poignant story of friendship gone awry, Vincent provided a crash course in oil business morality. When Shargel suggested that an attempted bribe by Vincent of U.N. Secretary-General Boutrous-Ghali, with Tongsun Park acting as intermediary, was illegal, Vincent shrugged and said the transaction would have involved “an Egyptian and a Korean,” as if that explained everything. Situational ethics were also on display when former SOMO official Mubdir Al-Khudhair took the stand. A resolute man with a slight Teutonic accent and the solicitous demeanor of a maître d’ at the best continental restaurant in a small American city in the sixties, he constantly referred to “Ohskar Vyatt,” and you practically expected to hear his heels click to attention each time. If Vincent appeared a little remorseful about goring his old friend, Al-Khudhair seemed almost giddily helpful to the prosecution. In short order he testified that Oscar had (a) set up front companies to purchase Iraqi oil once Saddam started instituting surcharges and (b) haggled over the price of those surcharges. This was in pretty stark contrast to Shargel’s earlier assertions that Oscar bought oil from the Iraqis legally and that he did not own the front companies. The witness also admitted that he once called Oscar “a son of a bitch” and “a weasel.”

Al-Khudhair seemed like a nice-enough guy, but on cross-examination Shargel managed to elicit the admission that the government had paid him $115,000 in relocation fees and moved his wife, son, daughter, and son-in-law to the U.S., all for the privilege of his testimony and access to a diary that contained notes about meetings to set up front companies in Cyprus and about Ohskar Vyatt’s illegal purchases of oil. (You can’t really blame Al-Khudhair for wanting to get the hell out of Baghdad; testifying without moving would have meant certain death for him and, most likely, his family. Then again, there were a few immigrants on the jury who might not have been too happy with the Iraqi’s instant admission into the U.S.)

It wasn’t hard to see how Oscar got himself into trouble with these guys. Al-Khudhair admitted that he was aware that Iraqi oil was sold improperly outside the U.N.’s Memorandum of Understanding, the face-saving Iraqi euphemism for the Oil-for-Food agreement. “But that is not corruption,” he insisted.

“You were transporting Iraqi oil in exchange for cash outside the Memorandum of Understanding?” Shargel asked.

“Yes,” Al-Khudhair answered.

“You were exporting Iraqi oil not approved by the Security Council?” Shargel asked, pressing for clarification.

“What does the word ‘you’ mean?” Al-Khudhair responded, taking a cue from Bill Clinton.

Still, Al-Khudhair did considerable damage to the defense, especially when he was asked about a particular meeting with Oscar. He blanched before responding, casting a nervous glance at the jury, and then said, “Maybe there’s some sensitivity here.”

When the judge told him to go on, Al-Khudhair anxiously eyed the jury again and said that Oscar had once asked another Iraqi oil official whether Al-Khudhair was part Irish. When he told Oscar that he was, in fact, part Austrian, Oscar supposedly said, “No, you don’t look like a Jew to me.”

“That surprised me,” Al-Khudhair told the court, before Shargel could cut him off.

As September droned on, the sky above Manhattan was crystal clear and the cool breeze was glorious, but inside the courtroom, Oscar slumped lower and lower in his chair behind the defense table. The accretion of information presented by the prosecution was pretty grim. There was a paralegal who displayed a list of purported surcharges that had been paid by Oscar through companies he claimed were not his but certainly appeared to be. There were audio recordings of phone conversations in which Oscar seemed to be calling the shots of those companies in an attempt to purchase oil from Iraq. There were e-mails and faxes to various Iraqi ministers and officials from Oscar that alluded to expediting payments of some sort or another. On one call that appeared in the filings but was never presented to the jury, Oscar demanded reimbursement for a surcharge from El Paso, the company that bought Coastal, because money “I’ve already paid to the bastards . . . came out of my hip pocket.” In another conversation, Oscar could be heard cackling for perhaps fifteen seconds. The jury laughed too. You could see they had joined him in Oscar World, bought into his duality, just like so many folks back home. They liked him—but that didn’t necessarily mean they were going to let him off.

Still, it may have been the prosecution that blinked first. The makeup of the jury had to have worried them all along, and then Shargel demolished a witness named Yacoub Y. Yacoub, another oil bureaucrat, who had been a finance official at SOMO. On direct questioning, Yacoub, through an interpreter, had professed to have prepared for Coastal a list of outstanding surcharges totaling $200,000. He had also stated that Oscar had paid another $7 million through multiple transactions via various front companies. But after holding himself out as an authority on the payments—no less than the creator of the Iraqi surcharge database—and going through a mind-numbing accounting lesson, Yacoub crumpled when Shargel started pressing him on the fine points. “I really do not remember. I really do not remember details,” he confessed (again, through his translator), his razor-sharp memory suddenly dulled by Shargel’s unrelenting disdain. “There are people who can remember everything they said, but there are other people who forget,” he whined.

That was on a Thursday, with no proceedings on Friday and the prosecution promising to wrap things up the following Tuesday. Shargel, to the disappointment of everyone who hoped Oscar would take the stand, announced casually that he planned to call no witnesses, which meant things were drawing to a close. His blistering cross-examinations would stand as Oscar’s defense. (“Who did we have to call but old Wyatt?” Carl Parker asked me. “He’s like a ninety-year-old accused of rape who’s so proud of it he wants to testify.”)

It may not have seemed like the perfect moment to strike a bargain, but over the weekend, an old deal floated by the prosecution surfaced again: somewhere between 18 and 24 months in prison and an $11 million forfeit, in exchange for a confession of one count of conspiracy to commit wire fraud. The truth was that both sides must have feared a hung jury, which would have meant millions more spent on a retrial with the outcome still in doubt. On Monday, October 1, reporters alerted by e-mail to a special 9:30 a.m. “proceeding of interest” found Oscar’s defense team a study in dejection. Shargel, in particular, had wanted to keep fighting, though he supported Oscar’s decision to plead. “Cases settle when you no longer want to assume the risk,” he told me, adding, “I didn’t originate the idea. I’m disappointed it didn’t go to verdict.”

Instead, Oscar stood before Judge Chin and cut his last deal—of this trial, at least. Chin began by leading him through a series of questions about his mental competency to make his plea. Then the judge said, “Mr. Wyatt, tell me what you did.”

Oscar spoke mechanically, as if it took all his will to answer: “On or about December of 2001, I agreed with others to cause a surcharge payment of 220,000 euros . . . to be deposited in a bank account controlled by Iraqi SOMO officials at the Jordanian National Bank. I caused facsimile transmissions and telephone calls to advise others to make this payment. This payment was in violation of the United Nations Oil-for-Food Program, because the program required that all payments be made directly to the United States escrow account in New York, and no money was to be paid directly to the Iraqi government.”

“Are you pleading guilty because you are guilty?” the judge asked.

“Yes, sir,” Oscar answered, though, not surprisingly, his voice lacked a certain conviction.

Sentencing was set for November 27; Oscar is to turn himself in to the authorities on January 2, 2008. His defense team believes he’ll serve at least six months in prison.

Polling the jury, both lawyers and reporters found that their instincts about a hung jury had been correct. Most jurors leaned toward a guilty verdict, but at least two told the Chronicle they would have let Oscar go. “I like you and I like Mrs. Wyatt,” one of them told Oscar as he was exiting the courthouse.

Oscar downplayed his plea, using a line similar to one he’d used to explain away other jams: “I didn’t want to waste any more time, at eighty-three years old, fooling with this operation,” he told the press. “The quicker I get it over with the better.” The next day, he was back at work at his desk in Houston, in an office in a high-rise where the air conditioner cooled like an arctic blast and the cars, trucks, and SUVs on the adjacent freeway burned up gas like there was no tomorrow. For an old Texas oilman, it was the only place to be.