One morning in October 1981, after finishing up the overnight nursing shift in the pediatric intensive care unit at Bexar County Hospital in San Antonio, Suzanna Maldonado stepped into the office of her boss. Pat Belko, the pediatric ICU’s head nurse, could not have been pleased to see Maldonado—the 25-year old registered nurse was not one of her favorites—and she was even less pleased when she found out what Maldonado had on her mind. Too many babies were dying in the ICU, she began—dying of problems that shouldn’t have been fatal. They were dying during a single nursing shift, the three-to-eleven evening shift. And they were dying, Maldonado said, under the care of a single nurse: Genene Jones.

Belko knew the ICU nurses had been trading such talk for weeks, maybe even months, but she considered it vicious gossip. Accusations like that, she scolded, shouldn’t be made lightly. But Maldonado wasn’t through. She had studied the ICU’s census book—the listing of patients and their condition during their stay in the unit. She had found out how many children had died during sudden emergencies and on which nursing shift the deaths had occurred. “It looks bad,” she told Belko.

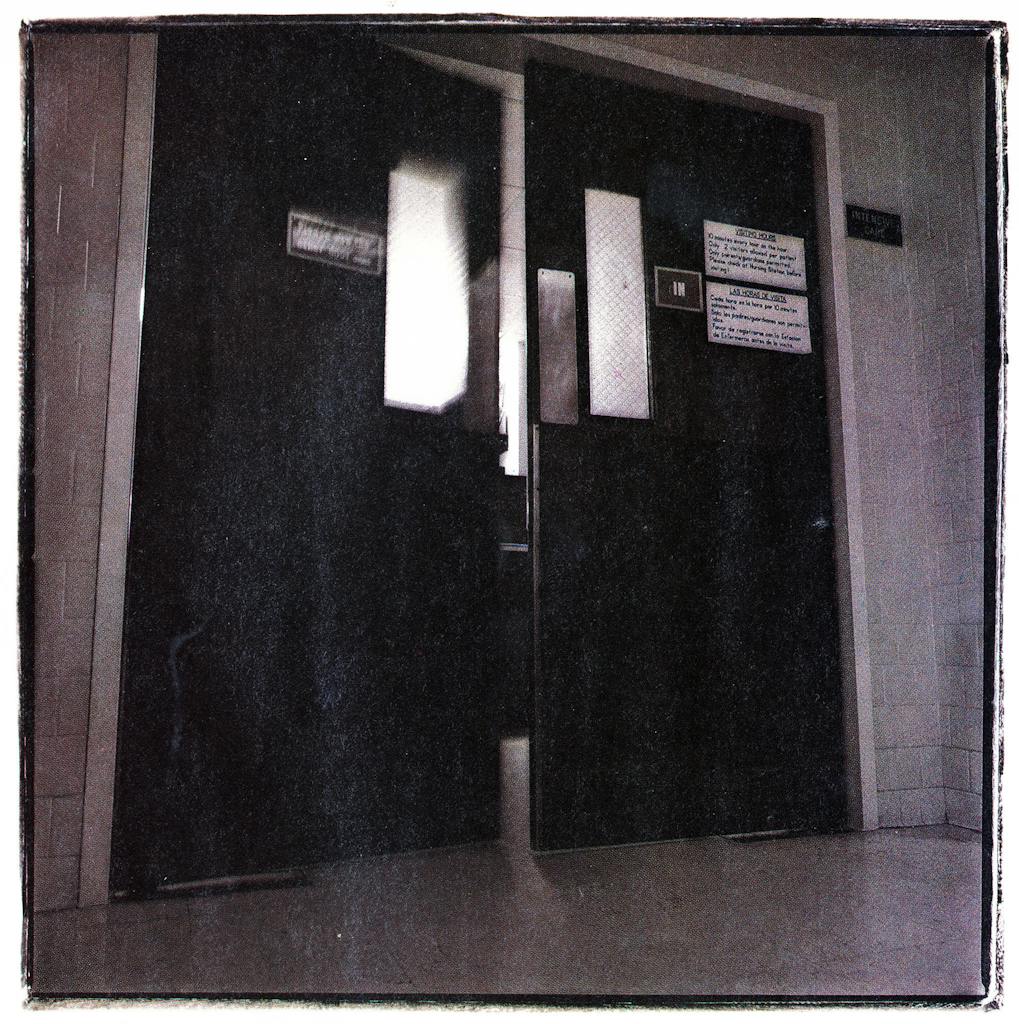

Belko sent Maldonado from her office and walked down the long fifth-floor corridor—past the little boys and girls playing in the hall, past the open rooms of children who had busted a leg or lost an appendix, past the kids who would soon leave the pediatric ward, happy and healed. At the end of the hall, she walked through swinging double doors into the eight-bed pediatric intensive care unit. This was a different world. Here the children were mostly still and silent, asleep on their beds, hooked up to tubes and monitors. The pediatric ICU was where Bexar County sent its critically ill children who could not afford a private hospital: the infant girl whose raging father had cracked open her skull, the two-year-old who had nearly drowned, the seven-year-old who was struggling to survive a congenital heart defect.

Belko walked over to the nursing station, pulled out the big blue census book, and flipped through it. Maldonado had done her homework; her numbers were correct. Dr. James L. Robotham, the unit’s medical director, was in the ICU finishing up his seven-thirty rounds. Belko asked to speak with him, and the two of them walked back to her office. She told Robotham what she had learned, and they agreed that there would have to be an investigation.

A short time later, Bexar County Hospital, a public institution created to save lives, began the first of a series of extraordinary private searches to determine whether one of its nurses was killing children. In the meantime, children in the pediatric intensive care unit continued to suffer, and sometimes to die, from unexplained medical problems. Kids who seemed stable suddenly stopped breathing. They had seizures. Their hearts halted or started beating irregularly. Babies pricked with intravenous needles began oozing blood, their clotting mechanisms inexplicably gone haywire. Time and again, the problems developed on the three-to-eleven nursing shift. Time and again, it seemed, they developed when Genene Jones, licensed vocational nurse, was on duty. Around cafeteria tables and in hallways, a growing number of people who suspected that something was terribly wrong began calling Genene’s hours on duty the Death Shift.

Between May and December of 1981, the last of the hospital’s internal inquiries found ten children in the ICU had died after “sudden and unexplained” complications. In all ten cases, Genene Jones was present at the child’s bedside during what the report gently terms “the final events.” The report concludes: “This association of Nurse Jones with the deaths of the ten children could be coincidental. However, negligence or wrongdoing cannot be excluded.”

But by the time that report was written, Genene Jones was long gone from Bexar County Hospital (which is now called Medical Center Hospital). Lacking definitive proof of wrongdoing, fearful of a lawsuit and bad publicity, the hospital administrators and the deans of the University of Texas Health Science Center in San Antonio, which trains its medical students in the hospital, were unwilling to fire Genene Jones, unwilling to call the police or tip off the district attorney. But the doctors who cared for patients in the pediatric ICU would not let her remain there—there was simply too much going on that medical science couldn’t explain. The administrators did not confront the problem directly; instead, they considered shutting down the ICU altogether. But they finally decided to move out all the licensed vocational nurses (LVNs), Genene Jones among them, under the cover of upgrading the nursing staff to consist only of registered nurses, who have more training than LVNs. Genene Jones and the others were given good recommendations and offered jobs in other parts of the hospital. Jones turned down the offer, and on March 17, 1982, she quit working at Bexar County Hospital. The “unexplained events” stopped.

After leaving San Antonio, Jones took a job with a pediatrician, Dr. Kathleen Holland, in Kerrville; in a period of 31 days, seven of Holland Jones’ patients had eight separate medical emergencies. One—a blue-eyed, fifteen-month-old girl named Chelsea Ann McClellan—died. And when Genene Jones left the town of Kerrville, the emergencies stopped.

Today, Genene Jones is free on a $225,000 bond from the Kerr County jail; she is scheduled to go on trial next month on a charge of murder. Ron Sutton, the burly country prosecutor for Kerr County, believes that Jones injected the seven children in Kerrville with a powerful muscle relaxant called succinylcholine chloride—which is sold by prescription under the brand name Anectine—a drug that leaves humans conscious but unable to breathe. Sutton’s grand jury has indicted Jones on one charge of murder and seven charges of injury to a child. In San Antonio, Bexar County district attorney Sam D. Millsap, Jr., is six months into an investigation of the mysterious deaths at Bexar County Hospital and why no one stopped them. Millsap says he is focusing his criminal investigation not only on Genene Jones but also on the Bexar County Hospital for its inaction.

This article is an account of what really happened inside Bexar County Hospital and the pediatrician’s office in Kerrville. Never, in the course of dozens of suspicious medical incidents and several lengthy investigations of them, has here been hard, irrefutable proof of what the prosecutors believe happened. No one but Genene Jones has been charged with a crime, and although Dr. Holland is the target of several private lawsuits that question her medical judgment, she will almost certainly not be indicted. And of course it remains impossible to say with certainty that the children who died were murdered. Still, it is possible to reconstruct the precise chain of events leading to their deaths, and so to learn some sad lessons. To see those events unfold is a revelation: it shows how palpable the sense of horror in the San Antonio hospital was; how poorly the sophisticated world of big-city medicine dealt with it; and how a group of small-town doctors finally took the decisive actions that apparently brought the tragedy to an end.

Both Ron Sutton and Sam Millsap have put forth theories about the reason for the babies’ deaths. Sutton believes that in Kerrville Genene Jones tried to create medical emergencies so she and Dr. Holland would look like heroes. In a town with an elderly population, Jones was determined, Sutton believes, to create a need for a pediatric intensive care unit that she and her friends would run. Millsap’s investigators in San Antonio have wondered about mercy killing, and they contemplated and then discarded the notion of a murderous lesbian clique. They now wonder about Jones’ lust for excitement and her contempt for inexperienced doctors. In any event, all the investigators are agreed on one point: at the heart of what took place in the case of the mysterious baby deaths is the complex personality of Genene Ann Jones.

“I haven’t killed a damn soul”

“I always cry when babies die,” said Genene Jones. “You can almost explain away an adult death. When you look at an adult die, at least you can say they’ve had a full life. When a baby dies, they’ve been cheated. They’ve been cheated out of a hell of a lot.”

I spoke with Genene Jones in May, three weeks before she was indicted and hauled off to jail. We talked in San Angelo, in a two-bedroom mobile home where she was living with three adults, three children, two cats, and a cocker spaniel named Sprout. Genene greeted me with a smile and sat down at one end of a Herculon sofa in the living room, opposite a small sign that read, “Always tell the truth no matter who it hurts.” Genene is 33 years old and five feet four. She carries twenty or thirty pounds more than she needs, even after losing weight since she became front-page news. She has hard, determined features, dominated by a large nose. Her short red-brown hair was neat that day, her makeup modest and careful. She wore purple slacks, a flowered blouse, and a gold chain around her neck. She had dressed for our meeting as though she were waiting for a Saturday night date.

In the middle of the couch, clutching Genene’s hand, was Garron Ray Turk, a pale, thin, blond-haired aide at a San Angelo nursing home. Garron is nineteen, and he is Genene’s new husband; they were married in San Angelo on April 24. He had little to say during the evening. He sat beside Genene, pecked her on the lips from time to time, and fetched more iced tea and cigarettes.

At the far end of the sofa was Debbie Sultenfuss. Debbie, 35 and also an LVN, met Genene when they were both working at Bexar County Hospital. Debbie grew up on a farm, where life moved slowly, and Genene’s fast mouth and mind quickly made an impression on her. In January 1980, shortly after they met, Debbie transferred from the pediatric floor to the pediatric intensive care unit and began working the three-to-eleven shift with Genene. They became inseparable: Genene the clever teacher, Debbie the eager, if slow, pupil. Debbie began trying to act like Genene, even to dress like Genene. But she was a poor imitation. Genene displayed a sharp mind and a sharper tongue; Debbie, a six-foot, two-hundred-pound giantess, lumbered. When Genene accepted the job with Dr. Holland in Kerrville, Debbie followed and took a job at the local hospital. When Genene got in trouble, Debbie moved her mobile home to San Angelo, and they settled in together. Debbie says she and Genene shared “a sisterly love.” Genene has gone to the trouble of publicly denying that she and Debbie are lesbians, and on this evening she pounced on that subject with an angry wave at her new spouse. “Ask my husband if I’m a les,” she said. “It’s nothing but trash.”

When the six o’clock news showed Genene Jones being taken to jail, viewers saw a broken woman, silent and defeated. It was a misleading picture. Genene Jones is a street fighter. She is articulate and intelligent—alternately friendly and defiant, sincere and threatening. She has an answer for every question, a response for every charge. When she hears that others have contradicted her account of the past few years, she goes on the attack: they are liars, “full of shit,” politically motivated, “a real turd”; she is right, they are wrong. She is quick to slip nasty tidbits about her accusers into the conversation—the RN who had an affair with a married doctor, the parents who made love in a hospital room as nurses walked in and out.

Her court-appointed lawyer, Bill Chenault of San Antonio, had told her not to talk about her case, but on this evening she had too much to say. “I’m sick and tired of being crucified alive and having people think I’m a baby killer,” she said. I haven’t killed a damn soul.” The deaths in San Antonio resulted from the mistakes of lousy doctors, she said, not from anything she had done. “Nobody did a damn thing up there. It’s all so much bull.” She had worked at other hospitals—why weren’t there suspicious deaths there? “I’ve been in nursing since 1977, and Bexar County’s the only place I’ve been killing people?” she demanded. “If you’re going to sit there and say that I killed babies, you’re going to have to tell me that a doctor ordered me to do it.”

No, Genene Jones is not about to shut up. “My mouth got me into this,” she said with a grin, “and my mouth’s going to get me out of it.”

The Making of a Nurse

Genene Ann Jones grew up in north-west San Antonio. She was one of four children adopted by Richard Jefferson Jones and his wife, Gladys. Dick Jones was a businessman, a bit of a wheeler-dealer who made a go of several different enterprises. When his children were young, he bought some property on Fredericksburg Road, cleared the site, and built a nightclub with a big dance floor inside and a patio and a pool outside. He called it the Kit Kat Swim Club, and he managed the place while Gladys spun records on the turntable. Genene was close to her father and loved to spend afternoons with him, helping to paint and put up the bill-boards he owned all over town. “We just had a ball together,” she says.

Dick Jones didn’t usually put up with much nonsense. He was an imposing figure—six feet tall, 240 pounds, and bald—and he didn’t believe in mincing words. His daughter developed the same trait. At John Marshall High School, she worked in the library, and when others weren’t working the way she thought they should, Genene would tell them what to do. “She was kind of bossy,” says the high school librarian, now retired. Genene was different from most of the other kids—more serious and less tolerant of teenage games.

One of Genene’s brothers died of cancer; another was killed by the explosion of a bomb he had made; and in January 1968, at the age of 56, Dick Jones died of cancer. June 15, shortly after graduation and a month before her eighteenth birthday, Genene married her high school sweetheart, James Harvey DeLany, Jr. Genene was a housewife for a few months, then enrolled at Mim’s Beauty School, became a beautician, and took a job at the Methodist Hospital beauty parlor. Her husband had been drafted into the Navy, and in 1970 they moved to Georgia, where she gave birth on January 19, 1972, in the town of Albany, to Richard Michael DeLany. They moved back to San Antonio, but by then the marriage had begun to collapse. Genene filed for divorce in Bexar County on August 10, 1972, claiming that her husband was “a man of violent and ungovernable temper and passion” who had been guilty of “unconscionable brutality and physical cruelty” and on several occasions had “struck her with great force.” Genene claimed they had been separated since mid-May, and she won a court order barring her husband from going near her or their baby son. Two months later it wasn’t necessary; the couple had reconciled, and the judge dismissed the suit.

The final breakup came on June 3, 1974, three months after Genene had filed again for divorce. But Genene Jones and James DeLany weren’t through with one another. They carried on a court fight for three more years. Genene filed suit against DeLany for failure to pay child support, and in August 1976, she won a contempt citation against him. DeLany asked for increased visitation rights, though Genene claimed he hadn’t been visiting Michael even when he was allowed to. On March 22, 1977, both agreed to drop the legal battle. On July 17 Genene Jones’ second child, Heather, was born. In a sworn deposition, she said the child’s father was named Ron English and that he was deceased. But she later on told Dr. Holland, her boss in Kerrville, that her ex-husband was the girl’s father—that Heather had been conceived out of wedlock during another brief reconciliation.

By the time Heather was born, Genene had moved in with her mother and was enrolled in San Antonio Independent School District’s School of Vocational Nursing. She did well in the one-year program: most of her grades were 90’s. And when she took her licensing exam on October 18, 1977, she scored 559—more than 200 points above the passing grade. She got a job at Methodist Hospital, but she was ushered out in late April 1978, after only eight months. “I had a conflict with a doctor,” she explains. “It was a lack of feeling on the physician’s part toward the patient, and I stood up for the patient, and he didn’t like it. They asked me to resign.” She moved across the sprawling South Texas Medical Center complex in northwest San Antonio to take a job in the obstetrics-gynecology ward at Community Hospital. After three months, she resigned to undergo minor surgery, and in October she answered an ad for ICU jobs at Bexar County Hospital. Genene began working in the pediatric intensive care unit on October 30, 1978.

Intensive Care

Genene says her first emotion on starting work in Bexar County Hospital’s pediatric intensive care unit was “stark, raving fear.” But she says her doubts about the switch from adults to children disappeared quickly. “The first baby I ever took care of was a preemie with a dying gut,” she recalls. “I picked that kid up and I knew I was going to stay there.” Cherlyn Pendergraft, the registered nurse who gave Genene her orientation, wasn’t so sure. The infant, a six-day-old boy with an often-fatal intestinal disease called necrotizing enterocolitis, went to surgery, returned to the ICU, and died. Genene had barely cared for the child, but “she just went berserk,” Pendergraft says; she broke into deep, wracking sobs, moved a stool into the dead baby’s cubicle, and sat staring at the body.

The pediatric intensive care unit where Genene Jones worked occupied a rectangular space the size of a two-car garage. During the 41 months she was there, the ICU contained eight beds, in separate cubicles with large glass windows that allowed the nurses to keep an eye on the patients and on the machines that monitored their heartbeats and breathing. In the back of the ICU was a small room where the nurses could sit and relax. It was filled with supplies and equipment for conducting simple lab tests.

While patients in the ICU may range up to sixteen years old, many of them are infants. Newborn children who are gravely ill go to the neonatal ICU, a floor below, where they receive more specialized care and are isolated from the infection that children who have been outside the hospital may bring in. The pediatric ICU is for kids who have been out in the world. Children are brought there to recover from surgery or to be treated for a disease or an injury.

Because the ICU is in a teaching hospital for the University of Texas’s San Antonio medical school next door, its medical staff consists of a rotating group of residents (most of whom graduated from medical school no more than three years earlier) and attending physicians who are faculty members at UT. The medical school provides the hospital with doctors and supervises the patients’ medical care; the hospital allows the doctors to use its patients in instructing students how to practice medicine. While Genene Jones worked in the ICU, the doctors made rounds in the morning and drifted in and out during the day; none worked there full time.

Therefore, in the pediatric ICU, even more than in most hospital wards, the nurses were an extremely strong presence. A pediatric ICU nurse spends all her time on one or two patients who demand almost constant attention; they are capable of doing nothing for themselves. Not all of them are on the brink of disaster, but many are. It is a situation where the work of a nurse can tip the scales between life and death. Nurses who choose ICU work do so because they like that kind of high-pressure challenge. They are bored with the low-key atmosphere out on the floor; they scoff at it as baby-sitting. ICU nurses pride themselves on their ability to intervene, to step between a disaster and a child like a superhero jumping in front of a speeding bullet; they pride themselves on being aggressive.

Genene Jones quickly came to think of herself as an ICU nurse. After spending her first three months at Bexar County Hospital working nights—11 p.m. to 7 a.m.—Genene moved to the 3 p.m. to 11 p.m. shift. But Bexar County, like many hospitals, had a nursing shortage, and Genene frequently volunteered to work over-time. Registered nurses, who have at least two years of training, often look down on LVNs, but Genene’s enthusiasm, knowledge, and technical skill impressed everyone. “For an LVN, she was absolutely excellent,” says Pat Belko, an RN who is the head nurse of the pediatric ICU. “She understood a lot of anatomy and physiology that was [on] a higher level than a lot of LVNs.” Pam Sturm, a RN who later supervised Genene for more than a year and became a close friend, admired her curiosity. “She was always inquisitive,” Sturm says. “If she didn’t understand something, she would pull out all my books and try to figure it out.”

But Genene’s most distinctive nursing skill was her extraordinary talent for putting intravenous lines into veins. Many hospital patients are given IVs to provide direct access to a vein—vital for injecting drugs, drawing blood, and giving fluids. Without IVs, nurses would have to turn patients into pincushions, sticking them a dozen times a day in a dozen different places. For a hospital nurse, starting an IV is a daily chore, but it’s one that many never master. Veins move under the skin, and it is easy to miss a few times before finding the mark. The job is even trickier with an infant, whose veins offer a target only the size of a thread. But for Genene it was a breeze. There was no IV she could not start, no vein too small, no patient too restless. Her reputation quickly spread, and nurses on the pediatric floor began calling her out of the ICU to start IVs for them. “She could stick an IV in a freaking fly,” says one doctor. Even those who disliked Genene conceded her technical skills. “She knew nursing,” says Pat Alberti, an LVN who worked in the unit. “She was probably the most competent nurse there.”

As Genene finished her first year in the ICU, however, her personality began to earn her as many enemies as admirers. She was loud and coarse. She thought nothing of bellowing out four-letter words or telling dirty jokes in a crowd of nurses and doctors. She spoke freely of the joys of sex, boasting of past conquests and pointing out those she had in mind for the future. The ICU was no convent, but Genene was saltier than most. She had strong opinions—about doctors, other nurses, patient care, the hospital—and she voiced all of them without hesitation.

In that group of medically aggressive nurses, she stood out as the most aggressive. She would spot problems in her patients before anyone else could see them—problems that the weary residents she dragged out of call-room beds often said didn’t exist. Exhausted doctors began to think of her as the most serious possible obstacle to a few hours’ rest: the nurse who cried wolf. “She’d always call you for crap,” says a former resident now in private practice in San Antonio. “After a while, you’d be tired of going over there. Any little thing, she’d be calling you—two, three, four times as much as anyone else. She wanted a lot of attention. After a while, you’d think she was a pain in the ass.”

If one doctor rejected her advice, Genene called another. “There was always a resident and an intern on to cover the evenings,” says Dr. Barbara Belcher, who completed her residency in 1981. “If the intern didn’t jump, she’d talk to the resident. If the resident didn’t jump, she’d go higher up.” Genene questioned medications, treatment, dosages, and diagnoses. When her recommendations for a patient were ignored, she predicted disaster. “This kid’s going to die if you don’t do this,” she told one doctor.

She issued her warnings to fellow nurses as well. Every eight hours, when shifts changed, the nurses would meet for “report,” during which those who had been on duty would describe the condition of their patients. “She would predict gloom and doom,” says Toni Grosshaupt, an RN who began working in the ICU in January 1981. “She would just say, ‘This patient is really bad; this patient isn’t going to make it through the night.’ It was like she knew what was going to happen. I was a new nurse. I’d come out of report shaking like a leaf.”

With parents of the critically ill children in the pediatric ICU, Genene Jones displayed a completely different personality. To them she was a comforting figure, a woman of patience and understanding. She had long talks with them. She listened to their complaints and fears. While faceless doctors rushed by, week after week. Genene was there, caring for their kid. She called them by their first names. She became a friend.

J.R.

In March 1980, Genene Jones gained an important ally: Dr. James Robotham, who that month became the medical director of the pediatric ICU and an associate professor at the UT medical school. Robotham, a 33-year-old pediatrician, came to San Antonio from the John Hopkins medical school in Baltimore, where he had spent three years. Before that, he had trained in pediatric intensive care at Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Children. Robotham is a brilliant, volatile, compulsive, and demanding man, and he quickly made his mark on the pediatric ICU.

Before his arrival, the role of the ICU medical director at Bexar County was a minor one. The job was part time, and the doctors who held it were content to let the individual physicians who admitted patients to the unit manage their care. But Robotham believed that critically ill children required care from someone specially trained to treat them; that, after all, was why he was there. He began spending much of his day in the ICU. He had little formal authority to hire, fire, or set policy, but through his presence and knowledge he shifted more and more of the burden for the patients’ medical treatment onto his own shoulders. He told residents and nurses to call him with any problem, at any hour. When the calls came in the middle of the night, he didn’t just tell his doctors what to do; he showed up at the hospital.

Fully conscious of his own abilities, Robotham wanted the nurses and residents to learn what he knew. At seven-thirty each morning he led them on teaching rounds, reviewing each patient’s condition and treatment plan. That routine goes on in every teaching hospital, but Robotham’s rounds were special. Residents accustomed to offering shallow presentations of a patient’s status suddenly faced an endless succession of pointed questions: What were the lab results? What do they mean? Why do you say that? Are you sure? When residents were caught short, forgot a dosage or a patient history, Robotham pressed them: Don’t you think it’s important to know? It was painful—Robotham often wasn’t satisfied until he had humiliated a young doctor—but the residents learned. He kept after the nurses as well. One day he walked into the ICU and there wasn’t a nurse or a doctor in sight; the nurses were meeting in the unit’s back room. Robotham went into a patient’s room and set off the alarm on one of the monitors. Nurses know those alarms are supposed to indicate a dire medical emergency, but no one came out. Furious, he walked into the nurses’ meeting and announced what had happened. The nurse whose patient he had picked broke into tears. The ICU staff quickly found a suitable nickname for the new medical director: they called him J.R.

It was only natural that he and Genene Jones would develop a rapport. The byword of Robotham’s style was “aggressive”; in Genene Jones he saw a nurse who personified that approach. If residents thought she overreacted, cried wolf, and woke them up too much, Robotham thought she was often right. “Robotham at the beginning was an absolute idol,” says Genene. “He is an absolute genius—unbelievably so. He’s astounding. He knows medicine with his eyes closed.” Most of all, Genene says, she admired Robotham’s approach. “What he said was look for subtle signs. Damn aggressive. He was extremely aggressive. And it was great.” When Pat Belko assigned another nurse to help him insert a special catheter in a child, Robotham said he wanted Genene instead. All her life, and especially since she had become a nurse, Genene had been sure she knew the right way to do things; now she had a superior who felt that way about her too. Robotham and Belko both encouraged her to take charge of the sickest patients. “They used to call me Robotham’s pet,” Genene says.

Codes and the Cold Room

In a hospital, a medical emergency is called a code. In the pediatric ICU where Genene worked, a code begins when a nurse notices that, for instance, a child has quit breathing or that his heart has stopped; she shouts over to the nursing station. Whoever is closest presses a small white emergency button, and an alarm goes out across the pediatric floor, bringing doctors running. When a nurse believes there is a severe emergency, she calls a code blue. An operator switches on the public address system and announces “code blue to pedi ICU” throughout the hospital, summoning help from everywhere. ICU nurses rush to the patient’s bedside with the unit’s “crash cart,” loaded with emergency drugs and equipment. People begin pouring through the ICU’s double doors: doctors on the floor, medical students from the pediatric ward, a team of respiratory therapists to handle resuscitation, a team of pharmacists to draw up drugs, residents, supervisors. The room fills with people. In the middle of it all, performing CPR or handling drugs, is the patient’s nurse, the one who called the code in the first place. The code may last for minutes or—when a child’s heart, like a sputtering motor, turns over but won’t quite start—it may last an hour. But in the center of the crisis, there is no consciousness of time. “You tune people out,” says Genene Jones. “It’s an incredible experience. Oh, shit, it’s frightening. You’re aware of everything, but you only tune in to two or three different people…You really have to control your physical abilities because you really get keyed up.”

When a child dies in the pediatric ICU at Bexar County Hospital, his nurse has the responsibility of taking the body down to the hospital’s morgue, a locked chamber in the basement known as the cold room. Often, after a doctor pronounces the child dead, the parents want to hold him one last time, in which case the nurse first has to clean the body—wash off the blood and pluck out the catheters and tubes that remain in it. When the parents are done, the nurse wraps the body in a blanket or a plastic shroud and calls a security guard to get the key to the morgue. If the child is large, the nurse places the body on a metal stretcher. If it is an infant, she carries the body in her arms.

Before the nurse leaves the pediatric ICU, the security guard walks down the long fifth-floor hallway, clearing the corridor and closing patient’s doors so they will not see the procession. The guard then walks with the nurse to a staff elevator that takes them to the basement, and there he unlocks the morgue door. “Especially at night, it’s very eerie down there,” says Elizabeth Stauffer, a pediatric ICU nurse who left Bexar County Hospital in 1979. “A lot of times, there would be patients who died during the day. Sometimes their bodies wouldn’t be covered. You’d walk into the cold room, and you’d see blood dripping out of every possible opening. It’s a creepy feeling.”

The codes and trips to the cold room are the dark side of working in the pediatric ICU, the part of the job that makes a nurse, every few months, ponder whether she wants to find a less difficult job. But Genene Jones seemed attracted to the dark side. By early 1981, she had begun asking for assignment to the sickest children. Many experienced nurses like the challenge of a critical patient and seek it out from time to time. But Genene Jones did more. She demanded the sickest patients. “She pretty much made her own assignment,” says Cherlyn Pendergraft. “She was so strong she ran like a charge nurse. She was just an LVN. She had no authority or power to do it, but she did it anyway.” Even when other nurses’ patients had emergencies, Genene was involved. “Any time there was an arrest, Genene was there—in the middle and helpful,” says Dr. Debbie Rasch, a former resident now working in the ICU. “It was like she enjoyed the excitement. She was around, even if it wasn’t her patient.” When a child didn’t make it, Genene broke down and cried. Crying over a longtime ICU patient was common, but Jones seemed deeply affected by every death. “When the kids died, Genene really grieved,” says one resident. “She’d say, ‘Before you call the mom in, wait a bit.’ She’d hold the baby and rock him.”

“Unexpected Events”

The first of the deaths in the pediatric ICU that later struck investigators as peculiar was that of Christopher James Hogeda. Christopher died at 7:32 p.m. on May 21, 1981, at the age of fifteen months. He was very sick; he had been at Bexar County Hospital for almost six months. When he was admitted in early December 1980, he had a severe congenital heart defect, pneumonia, and diarrhea. In May, he developed hepatitis, and infection spread throughout his body. Several times his heart began beating irregularly. He died of a cardiac arrest.

When Chris Hogeda died, Genene Jones erupted into tears. “He was my boy,” she says now; she had cared for the child for months. During that time, Genene had won the friendship of Chris’s parents, Diana and Crecencio Hogeda, Jr. (More than a year later, when Genene, in deep trouble, needed to leave Kerrville, the Hogedas suggested that she move to their hometown of San Angelo, and Genene accepted.) Now, with Chris gone, his parents had been summoned, and Diana Hogeda had asked Genene over the phone to wait in his room until they arrived. It was more than an hour. Genene had pulled the plastic tubes out of Chris’s body and washed him, crying and talking out loud all the while. “I would bathe the children, and I would sing to them while I bathed them,” Genene says. “If that sounds insane, tough shit. If you can’t die with dignity, why live with dignity?” She pauses. “We talked to them even after death. We’re not God. We don’t know when the spirit leaves the body.” Genene finished cleaning Chris Hogeda and wrapped his body in a blanket. She settled into a chair and held the corpse to her chest while she waited for his parents to arrive.

During 1981, nine more children died in the pediatric ICU after “unexpected events” (in the words of one internal report). But those deaths are merely landmarks—cases in which investigators, months later, found written evidence of something peculiar. Nurses and doctors who worked in the ICU recall many more unexpected emergencies—many of them nonfatal—in 1981 and early 1982. “It began to happen more frequently until it happened every day or two,” says Toni Grosshaupt. Patients would come into the unit, sick but suffering from problems children had been able to lick in the past, and die. Was there some mysterious germ in the air? The nurses wondered. A San Antonio version of legionnaires disease? As the summer of 1981 wore on, the problems became more frequent, and the nurses began to connect them to Genene. “I’d leave a patient I thought was stable,” says Grosshaupt. “She’d come on, and I’d find out the patient had a bad spell—had seizures or codes. That happened consistently.” Pat Alberti remembers several evenings when she arrived at 10:45 for work to learn that a child she cared for the previous night was dead. “I struggled with it for eight hours, and the kid was still alive,” she says. “Day shift had it for eight hours, and the kid was alive. [Genene] came in for three hours, and the kid was dead.”

Pat Belko, the head nurse, knew there were whispers about Genene. She says she didn’t think twice about it. “It was real hard to think that somebody who seemed to care so much about patients and get along so well with families would be doing something of this nature,” she says. “The two of them just didn’t seem to fit together.” She knew that the nurses who were talking the most didn’t like Genene. And she knew they had no proof. Belko told them to either document their suspicions or knock it off.

Genene herself seemed devastated by the rash of deaths and near-deaths in the ICU. In September, another of her patients died, and Genene fell into a chair in the corner of the ICU and broke into tears. Debbie Rasch walked over to comfort her, and Genene looked up, her eyes red and puffy. “Why do babies always die when I’m around?” she asked.

Suzanna Maldonado began working in the pediatric ICU in 1980, less than a year after getting her RN degree. She was on the eleven-to-seven shift—the one following Genene’s—and friction soon developed between the two women. Genene thought she knew more than Maldonado and considered her a spoiled child; Maldonado thought of Genene as an aggressive LVN who tried to make people think she knew more than she really did. When children began having more and more unexpected problems during the summer of 1981, Maldonado was among the first to notice—and to make the connection to Genene Jones. “I thought, ‘All these children died in the same period of time, and it just so happened that Genene was taking care of them,’” she says. “If the kid was sick, why didn’t he die on me? Why didn’t he die on somebody else?” She began making a point of reviewing what Genene had done. She started thinking about the number of children who had died. By October she was ready to go to Pat Belko—ready for the confrontation that convinced Belko that she should take the suspicions about Genene to Dr. Robotham and persuade him to launch investigation.

October 10, 1981: Jose Antonio Flores, six months and three days old, died in the ICU at 5:22 p.m. Admitted on October 6 for fever, vomiting, diarrhea, and dehydration, he developed seizures during his third day in the pediatric ward and was taken to the hospital basement for a brain scan. While there, he went into cardiac arrest. Doctors revived him and brought him to the pediatric ICU, where they noticed he was bleeding uncontrollably. He arrested a second time, and doctors tried for 52 minutes to revive him, but they failed. The child’s death certificate says the bleeding caused the fatal cardiac arrest. The cause of bleeding, it says, is unknown; there was no autopsy. Handwriting on Jose Antonio Flores’ medical records, says an internal report, indicates that Genene Jones was present during the brain scan.

Blood Thinner

From the beginning, Dr. Robotham had worried about heparin. Several children, like Jose Antonio Flores, had developed bleeding problems in the ICU. Blood would leak from old needle punctures, ooze out of suture sites, their mouths, even their rectums, until finally their blood pressure would drop, putting severe strain on the heart. Doctors had been diagnosing the bleeding as symptomatic of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), a relatively rare condition often caused by severe infection, which can set off a reaction that keeps blood from clotting. But there seemed to be too many cases. The problem had never cropped up with such frequency before. There was one other possibility: heparin, an anti-coagulant that doctors and nurses used every day in the pediatric ICU; a small amount kept intravenous lines from clotting with blood. Was someone giving the children too much? Or could there be a more innocent—though equally deadly—reason, such as a faulty batch of heparin? Was someone giving children overdoses of other drugs as well?

Robotham told Pat Belko that he wanted the heparin handled more carefully. Each nurse was told that she had to have a second nurse watch whenever she drew heparin from its container. Both nurses would have to initial the bottle to show who had conducted and witnessed the procedure. In early November Robotham briefed Dr. Robert Franks, acting chairman of the pediatrics department at UT, and Franks asked him to review all deaths in the ICU over the past several months and report back in writing. In the meantime they decided to begin a full-scale effort to separate true DIC cases from possible heparin overdoses. Establishing an overdose of heparin or some other drug, they knew, would require extensive laboratory tests. Robotham met with the pediatric residents and ordered them to draw and send to the lab an extra blood sample whenever a child developed unexpected problems. Franks filled in the Bexar County Hospital District’s executive director, B.H. Corum, who then asked Franks to keep John Guest, the hospital’s administrator, informed.

December 22, 1981: Doraelia Rios, 25 months old, died at 8:12 p.m. She had been hospitalized several times previously for gastrointestinal surgery, and she entered the hospital again on December 21, suffering from diarrhea, dehydration, and possible inflammation of an internal membrane. She was given fluids to deal with the dehydration and antibiotics to fight the infection, but she suffered a fatal cardiac arrest. Genene Jones was there during the arrest and finished her nursing notes with a brief remark: “A legend in her own time. Merry X-mas Dora. I love you. Jones LVN.”

“I Want Him Out Now!”

By early January 1982 Robotham had completed his review of the ICU’s medical records. It revealed no evidence of wrongdoing. Franks notified Corum, and they relaxed a bit. Maybe there wasn’t a problem. Judy Harris, a nursing administrator, had begun her own review of the records, but there still was no solid evidence of anything—not until Rolando Santos.

Rolando Santos entered Medical Center Hospital (the name was changed from Bexar County Hospital that month) on December 27, 1981, at the age of four weeks. He had pneumonia and breathing problems, so after admitting him to the pediatric ICU, doctors placed him on a respirator. On December 30, he suddenly went into seizures, but a brain scan revealed nothing that would explain the problem. Then he had a cardiac arrest, but was revived. On January 1, his blood pressure fell; he was bleeding from old needle-puncture sites. On January 6, he began bleeding again. Dr. Ken Copeland, a boyish-looking pediatric endocrinologist with a mop of curly hair, was the attending physician in the pediatric ICU. He ordered tests for the presence of heparin. They came back positive.

When Rolando Santos began bleeding again, on January 10, Copeland was ready. He called the hospital pharmacy and ordered a does of protamine—a drug used to reverse the effects of heparin. The child was given the drug, and he quickly stopped bleeding. On January 12, when he came in for rounds, Copeland ordered nurses to transfer Rolando Santos out of the pediatric floor, even though he was really too sick to leave the ICU. Early in the afternoon of that day, Copeland returned to the ICU and found that Rolando was still there. He was furious. “I want him out now!” he told the nurses, and they wheeled him out of the ICU, onto the main pediatric ward. Four days later Rolando Santos was well enough to go home.

Now, for the first time, there was real evidence of a heparin overdose in the pediatric ICU; in response, Robotham ordered heparin removed from patients’ bedside tables and kept in the drug cabinet with the narcotics. Franks, who had been receiving daily reports from Robotham on developments in the ICU, on January 19 dictated a memo to the dean of the UT medical school, Dr. Marvin Dunn. “From the outset there had been innuendo that purposeful nursing misadventure was involved,” Franks wrote. Robotham’s review of the charts “could not substantiate that suspicion.” But now, Franks told Dunn, there had been a documented case of heparin overdose; there was laboratory proof of it. Though the problem had not been linked positively to any one employee, Franks wrote that he had returned “to a position of not knowing whether or not there is a problem.”

“I have several obvious concerns,” he went on. “One is that there will be inappropriate comments resulting in unjustified publicity.” To avoid that, Franks would personally conduct a second review of the deaths in the pediatric ICU. “We are continuing to evaluate ‘unexpected events’ in the unit in a formal way,” he concluded.

Two days earlier, on January 17, a baby named Patrick Zavala had died in the pediatric ICU. Patrick, four months old, had been brought to the ICU after an operation on his pulmonary artery. During the evening shift he suddenly experienced irregularities in his heartbeat, and he died at 9:45 p.m. Nurses in the ICU were so puzzled by his death that three of them sat in on the child’s autopsy the next morning. But if they were puzzled, the hospital’s surgeons were furious. For months, the surgeons had been upset about what was happening to their postoperative patients in the pediatric ICU. This was the last straw.

Dr. Kent Trinkle, a moody but highly regarded chest surgeon, talked to Dr. Howard Radwin, another surgeon who was serving as head of the medical-dental staff. On January 21, the two men met with B.H. Corum, the director of the county hospital district. Something had to be done, Trinkle told Corum; he would send his pediatric patients elsewhere if things didn’t change. Corum said they would.

Corum set up a meeting on January 25 with Paul Green, the hospital’s malpractice attorney, and invited Bill Thornton (the hospital district’s board chairman), Marvin Dunn (the medical school dean), and a handful of others. The group met in Corum’s office, and the problem was put to the lawyer: there was trouble in the pediatric ICU and a single nurse was in the middle of it. Could they fire her? Should they call in the district attorney? Green listened and asked questions: Was there proof that the nurse was doing something? The doctors and administrators told Green there was none. The problem was described as a matter of poor leadership in the pediatrics department and a “catfight” among nurses, according to Thornton. “I asked, ‘what are the numbers, what is the mortality rate?’” recalls Thorton. “They said, ‘No, that’s not a problem.’” Green offered his advice. Without facts, he told them, firing Genene Jones or calling the district attorney would put them on shaky legal ground. She could sue them, and she might well win. The administrators and doctors decided to continue the internal investigation but otherwise to keep the whole thing quiet.

The Investigation

When Dr. Alan Conn arrived in San Antonio in January 1982, Marvin Dunn called him into his plush second-floor office at the medical school. Conn, a 57-year-old anesthesiologist at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto, had run the pediatric ICU there for twenty years; now he had a six-month sabbatical, and he had arranged to spend it as a visiting professor in San Antonio, doing research in a medical school lab on drowning victims. Dunn knew that Conn’s hospital had conducted an investigation of its own into reports that a nurse (who was indicted, tried, and not found guilty) was harming children with drugs. In his office he explained to Conn the problems the Medical Center Hospital had been having and asked him to begin yet another investigation of the pediatric ICU.

As Conn rounded up his team to evaluate the ICU, the level of tension there rose steadily. The nurses had become reluctant to prepare any kind of drug without a witness. “Everybody was having people check and double-check them,” Dr. Debbie Rasch says. “You double-checked with another nurse. Then you double-checked with a doctor. Then you had the nurse and the doctor standing there when you gave the medication… A lot of us felt like we couldn’t go to sleep, because we had to keep watching to make sure nothing happened. It was a real stressful time.”

Everyone knew that Genene Jones was the prime target of suspicion. “They’re out to hang me,” Genene told Glory Ann Johnson, another nurse, one day. “They might as well let me go.” Robotham, once her protector, had turned against her. One day she confronted him. “I asked him if we could talk; I asked him what the hell was going on,” she remembers. “I said ‘Do you think I’m doing something to the kids?’ He said, ‘Yeah.” I said, ‘Why?’ He said he didn’t know.”

Another day, she used a less subtle approach. “This unit is my life,” she told Robotham. “If you try to take me away from this unit, I have my black book with the name of every kid who’s died in the unit and the doctor who caused the death.” Genene had made references to a black book when talking to other nurses and administrators. She wouldn’t leave, she announced, “without a bang.” Belko and a nursing administrator called Genene in and questioned her: Did she have such a book? Genene backed down; she said she did not. Robotham told Belko he wanted Genene fired, or at least out of the ICU. But Belko only took her off the most critical patients for a week.

To conduct his investigation of the pediatric ICU, Alan Conn assembled a high-powered team of six specialists: the medical directors and head nurses of pediatric intensive care units at three prominent hospitals. They began work on February 15, meeting in a conference room at the medical school and bringing in witnesses one at a time: nurses, residents, administrators, senior pediatricians, and surgeons. They got an earful. Almost everyone was angry at someone, and most were willing to speak their mind—especially about Genene Jones. The hospital’s employees had been told that Conn’s group was doing a routine review of the ICU, the sort of study that takes place in all hospital departments from time to time. But no one believed it.

When it came time to analyze the ICU’s problems, the committee members decided to view the complaints about Genene Jones merely as a symptom of a broader malady. Their report makes no mention of her name; after all, there was never anything but circumstantial evidence to link her to the incidents in the ICU. “You don’t pay much attention to rumors of increased mortality,” says Conn. “When you have a limited number of trained and experienced people, they tend to get the sickest kids. If the kids die, it’s only a minor step to saying they must be doing something wrong.” But the Conn report is extremely critical of the operations of the ICU, to the point of raising the possibility of closing it temporarily. The committee made many stern recommendations, among them that James Robotham and Pat Belko be relieved of their duties.

Looking for a graceful way to accomplish this, the committee suggested a new job for Robotham: director of critical care research. But Robotham didn’t buy it. He told friends he thought he’d been screwed, resigned his position at the medical school, and in June 1983 returned to Johns Hopkins. Belko was luckier; a last minute plea by Virginia Mousseau, her boss, won her a reprieve. She was placed under close watch for a six-month unofficial probationary period, and when it was over, she kept her job.

The problem of Genene Jones was solved by recommending that the hospital administration replace all LVNs in the unit with RNs, on the grounds that most big-city pediatric ICUs had all-RN nursing staffs. There were six LVNs besides Genene, and one of them had been there since 1969. They would all have to go. “It was a case of having to use a huge stick because it was impossible to single out one,” says Dr. Arthur McFee, chairman of the surgery department. “If we had just gone out and fired her, we would have had a substantial suit.”

At about noon on March 2, 1982, Pat Belko passed the word that Virginia Mousseau, the hospital’s top nursing administrator, wanted to talk to the pediatric ICU nurses. The meeting was to begin at three o’clock. Agency nurses kept an eye on patients while the staff members from two shifts crowded into the ICU’s small back room. According to people who were at the meeting, Mousseau told the nurses that the ICU was good, but the hospital administration wanted to make it better. They were going to upgrade the unit. Dr. Conn had made a recommendation, and they were going to follow it and move to an all-RN nursing staff. The LVNs would all be offered other jobs in the hospital, Mousseau said, and would have until March 22 to leave the ICU.

The room exploded in tears and shouts. It wasn’t right, the nurses told Mousseau. She answered that the move was part of a trend; most ICUs had an all-RN staff. Finally Genene spoke up. “If you want a scapegoat, take me,” she said dramatically. “We know you just want to get rid of me. Let me go, and let the rest stay.” No, Mousseau assured her, the move wasn’t directed at any one person. The hospital administration planned to employ only registered nurses in all its ICUs; the pediatric unit just happened to be the first. The ICU would be scaled down to four beds, she added, so it could absorb the loss of the LVNs.

A few days later, Suzanna Maldonado found a note in her mailbox at the hospital. It was written on hospital scrap paper, and it said, “Your dead.” Maldonado turned the note over to Pat Belko. The next day another note arrived on a small white piece of paper, bearing a single word: “Soon.” This time Maldonado turned the note over to hospital security.

The hospital’s nursing administrators began individual meetings with the LVNs. They would all have the opportunity to take other jobs at Medical Center Hospital, they were told, and they would all get good recommendations. Genene was told that there were no pediatric positions available and was offered a place elsewhere in the hospital. But by then she had other options. She had accepted a job offer from Dr. Kathleen Holland, a third year pediatrics resident at Medical Center Hospital who was just getting ready to start her own practice in Kerrville.

The New Doctor in Town

Kathleen Mary Holland often told her friends that she was amazed she had ever become a doctor. Early in her life her ambitions didn’t reach much higher than the basement of the Albany, New York, public library, where she worked as a clerk-typist. She was the only child of two factory workers, and though her parents moved often, they never left their working-class neighborhood in North Albany.

Kathy quit high school after her father died in 1963, in the middle of her junior year, and when forced to return she misbehaved so badly that the principal wouldn’t let her go back for her senior year. She graduated instead from a black high school on Albany’s south side, and until she met and married a librarian named Larry Doyle, she hadn’t thought much about going to college. But Larry, twelve years older and extremely demanding, wouldn’t let her settle down. She started taking science courses at the local community college, and when Larry found work in Tucson, she enrolled at the University of Arizona as a biology major. In 1971, after Larry got a job in New York at Cornell University, she enrolled there and completed her undergraduate degree. Kathy wanted to become a veterinarian, but after Cornell’s vet school turned her down twice, she and Larry moved to San Antonio, and she started thinking about studying human medicine. In July 1974, she enrolled at the University of Texas Health Science Center, working toward a medical degree and a Ph.D. in anatomy. Third-year rotations at Bexar County Hospital quickly helped her to decide to specialize in pediatrics. “Nobody seemed to be showing each other how much they knew,” she says. “Nobody was putting on airs. Nobody was arrogant. Everybody was just sort of people. Everybody walked into a room with pediatric patients and smiled and joked.”

Kathy and Larry and three cats had settled into a frame house in Bulverde, in Comal County, and she stayed an extra year at the medical school to try to finish her Ph.D. But problems developed with her research project—and, at the same time, with her marriage. Kathy and Larry’s divorce went through on July 27, 1979. By then she had moved in with Charleigh Appling, a retired Air Force colonel who was a campus police officer at the medical school.

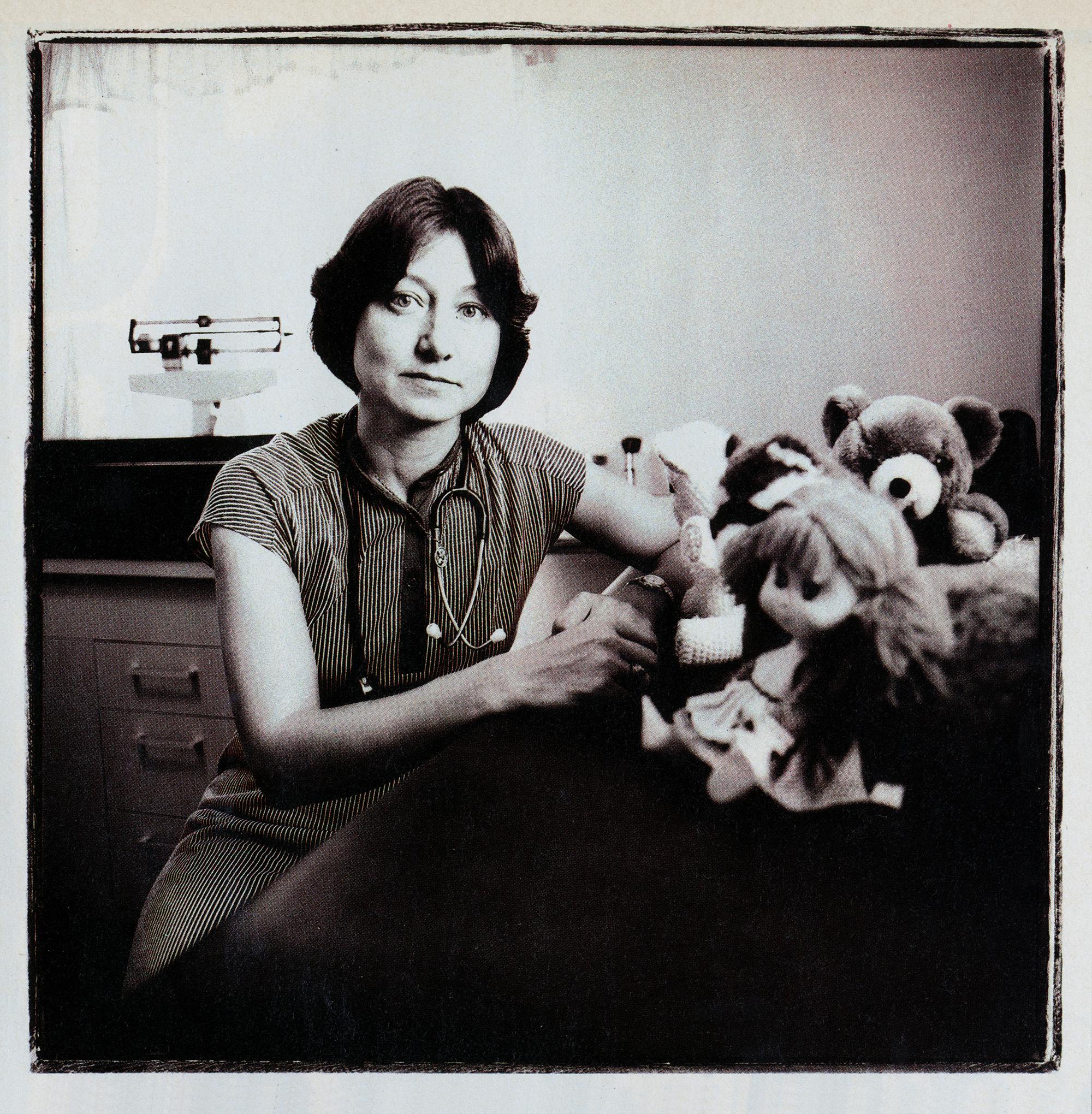

She began her three-year pediatric residency at Bexar County Hospital in July 1979 and quickly impressed her fellow residents as a hardworking, capable—and aggressive—student. It took her just a few months to decide that after the residency she would go into private practice in Kerrville, sixty miles northwest of San Antonio, an affluent, pretty Hill Country town of 15,000, filled with retirees. There was a growing population of young families and just one pediatrician. The doctors there, all of them men, encouraged her move to town. Kerrville also had the largest general hospital in the area: the 120-bed Sid Peterson Memorial Hospital, a strong institution that was weak in pediatrics because Kerrville had for years been a town of old people. Here was a challenge, she thought: to bring modern pediatric medicine to Kerrville.

The hospital’s lack of experience with pediatrics made Dr. Holland determined to find a nurse with good technical skills for her private practice. “The nurses of Sid Peterson really weren’t comfortable with starting pediatric IVs,” she says. “They really weren’t comfortable with drawing blood on kids younger than two…I wanted to take a nurse with me who had those skills, who had been through the codes. I wanted someone who would start IVs for me, who could draw meds for me. I was really worried about going into a whole new community where they did not have pediatric nursing skills at a level that I knew, and not having anyone to help me.”

Holland’s first choice was Pam Sturm, an RN. “You can’t afford me,” Sturm told her; she was making $8.35 an hour. “What you need to look for is an LVN.” An LVN would make about $5 an hour. Kathy Holland spoke to a handful of prospects. Then, she says, in the summer of 1981, she brought up the subject with Genene Jones.

Kathy Holland was one of the few residents Genene Jones admired. Unlike many of the young doctors, she didn’t seem to mind Genene’s constant questions; she respected her judgment. When Genene called to say something was wrong with a child, Kathy Holland came running. “If Genene says something’s going to go wrong,” Holland told another resident, “then it usually does.”

Genene says Dr. Holland didn’t talk to her about Kerrville until late 1981—and that her initial response was no. “I originally told her no because of all this stuff going on,” she says. “I told her no two or three times.” Finally, Genene says, when Holland arrived in the ICU with floor plans for her new office in Kerrville, she accepted. “She just sat there, already talking about the clinic,” says Genene. “The rumors were flying, and it sounded real good. It sounded peaceful and calm.” They agreed to begin in Kerrville in August.

Kathy Holland knew there were suspicions about Genene Jones. One day in early 1982, Holland’s best friend among the residents, a doctor named Jolene Bean, sat down with her and suggested that perhaps she should change her mind about hiring Genene. Yes, Holland told her friend, she had heard the gossip that Genene might be doing something to the children, but she had worked with Genene Jones. She didn’t believe it. “Nothing I ever saw fit that pattern,” she says now. “You show me a puppy that comes up to me and licks my hand. Somebody comes up to me and says, ‘That puppy just tore up my leg.’ You gotta show me.” Holland talked to Pat Belko, who backed Genene, warning only that she was an assertive person and that Holland would need to define clearly the limits of Genene’s responsibility. Wanting still more advice, Holland approached Dr. Victor German, a pediatrician who had assisted James Robotham in the ICU for the past several months. “This is a new office and a new community that really needs pediatrics,” she told him. “I’m not asking for you to disclose any absolute evidence. Just tell me: Is it a good decision to continue, or should I reconsider? Do you think there’s a possibility Genene could be doing something to hurt kids? ‘No, I cannot imagine that,’” Holland says German told her.

Later, Holland ran into Robotham outside his laboratory in the medical school. He asked for a word with her, and she recalls that he said, “Hey, I hear you’re taking Genene to Kerrville. You better think twice. There’s a lot at stake up there.” Robotham mentioned the case of Rolando Santos, the child whose repeated bleeding had been documented as a heparin overdose. Holland said she’d heard that the tests on the child’s blood had been performed shortly after he had been given heparin to clear clots from an arterial line. Robotham told her he had other suspicions. She thought he seemed vague.

By June 30, 1982, the end of her residency, Holland had received several evaluations of the nurse she had hired, and most of them were favorable. The hospital had given Genene a good recommendation and offered her another job—hardly possible if administrators believed she was harming children, Holland thought. Robotham and some nurses had their suspicions, but their ill will toward Genene was clear. And besides, Holland knew Genene Jones. She would not withdraw her job offer. “How were you to think this was anything but personal when all these things were coming from people who hated her anyway?” she says. “I trusted her implicitly.”

Dr. Kathleen Holland slumped into the last chair left in her pediatric clinic one afternoon in April of this year, looked around at the vacant office, and cried. It had been such a wonderful place to begin her career: the Fine Medical Center, a busy complex of doctors’ offices less than a mile from downtown Kerrville and Sid Peterson Hospital. She had signed a five-year lease and spent hours selecting wood stains for the cabinets and soothing colors for the walls. Now, at the age of 36, she was moving out, a step ahead of the sheriff and a few steps short of bankruptcy. The patients had stopped coming when the publicity hit, but the bills hadn’t, and there just wasn’t enough money to pay the landlord. Even now, he was hovering outside, watching Dr. Holland and a handful of friends pack up her things.

Already the parents of three children she had treated had filed lawsuits against her and Genene Jones. Holland and Charleigh Appling, who had gotten married on April 17, 1982, had divorced on December 30, in hopes of saving Charleigh’s assets from the creditors. The grand jury had not yet cleared her. And Sid Peterson Hospital had refused to restore her hospital privileges. She had been naïve to trust Genene, Holland told her friends—naïve and stupid. Now she was paying for it.

Dr. Holland opened her new pediatric clinic on August 23, 1982. She had originally planned to start at the end of the month, but Bill Schick, her business manager, suggested that starting up a week early might bring in a bit of business from preschool physicals. Genene Jones, after leaving the Medical Center Hospital, had worked for Medox, a San Antonio nursing agency near the hospital, and spent a few months at the Santa Rosa Medical Center, a large nonprofit private hospital in downtown San Antonio; On August 3, Genene’s nursing license expired. The Texas Board of Vocational Nurse Examiners did not receive the fees to renew it until November 29, 1982; during the entire time that Genene worked for Dr. Holland in Kerrville, she was practicing nursing without the valid license required by state law. In late summer, she began looking for a place to live in Kerrville, and when she had trouble finding a landlord willing to accept a tenant with both children and animals, Holland decided to buy a small house next to her and rent it to her. The real estate agent found a $45,000 place on Nixon Lane, in an isolated subdivision in the hills seven miles outside of town. Holland bought it, and Genene rented a U-Haul and moved in.

Kathy Holland planned to live outside the hamlet of Center Point, on a rugged sixteen-acre tract fifteen miles south of the clinic. Charleigh had bought the land in May 1980 with the help of a Veterans Land Board loan, and they’d been dreaming of living there ever since. They would have peace and quiet, beautiful countryside, and room for two horses that Kathy was boarding at a stable. They would live in an underground home that Charleigh would build into the side of a hill as soon as the pediatric practice was flourishing; in the interim, he would build a smaller house on the property. As August 1982 arrived, the first house was little more than a wooden frame. Charleigh often spent nights at the site in a sleeping bag to keep an eye on things. There was no bathroom there, and Dr. Holland found it difficult to dress for work without a shower or hot water. So she arranged to stay on Nixon Lane for a while.

Debbie Sultenfuss, like Genene, had worked at Medox for a time. Then, in May 1982, she moved to Kerrville and began working in the intensive care unit at Sid Peterson Hospital. Debbie moved her trailer to Kerrville, but she said the utility company was slow hooking up the electricity. She, too, spent many nights at the house on Nixon Lane.

In August, Dr. Holland hired a secretary-receptionist, a tiny 33-year-old woman named Gwen Grantner, who had bounced from job to job in Kerrville. She was less than five feet tall and weighed about 85 pounds—and she talked nonstop. She was born in Chicago, and though she had never been to England, she spoke with a strong Cockney accent. Gwen told Holland she’d been married to a Briton, found his manner of speech appealing, and decided to affect it herself. The new doctor was intrigued. “She had this neat accent,” says Holland. “She was very honest about things, and I liked honesty. She’d said she had a lot of different jobs, but that was because of disagreements.” Holland asked Gwen Grantner to join her fledgling medical office. The staff was complete and the office ready to open.

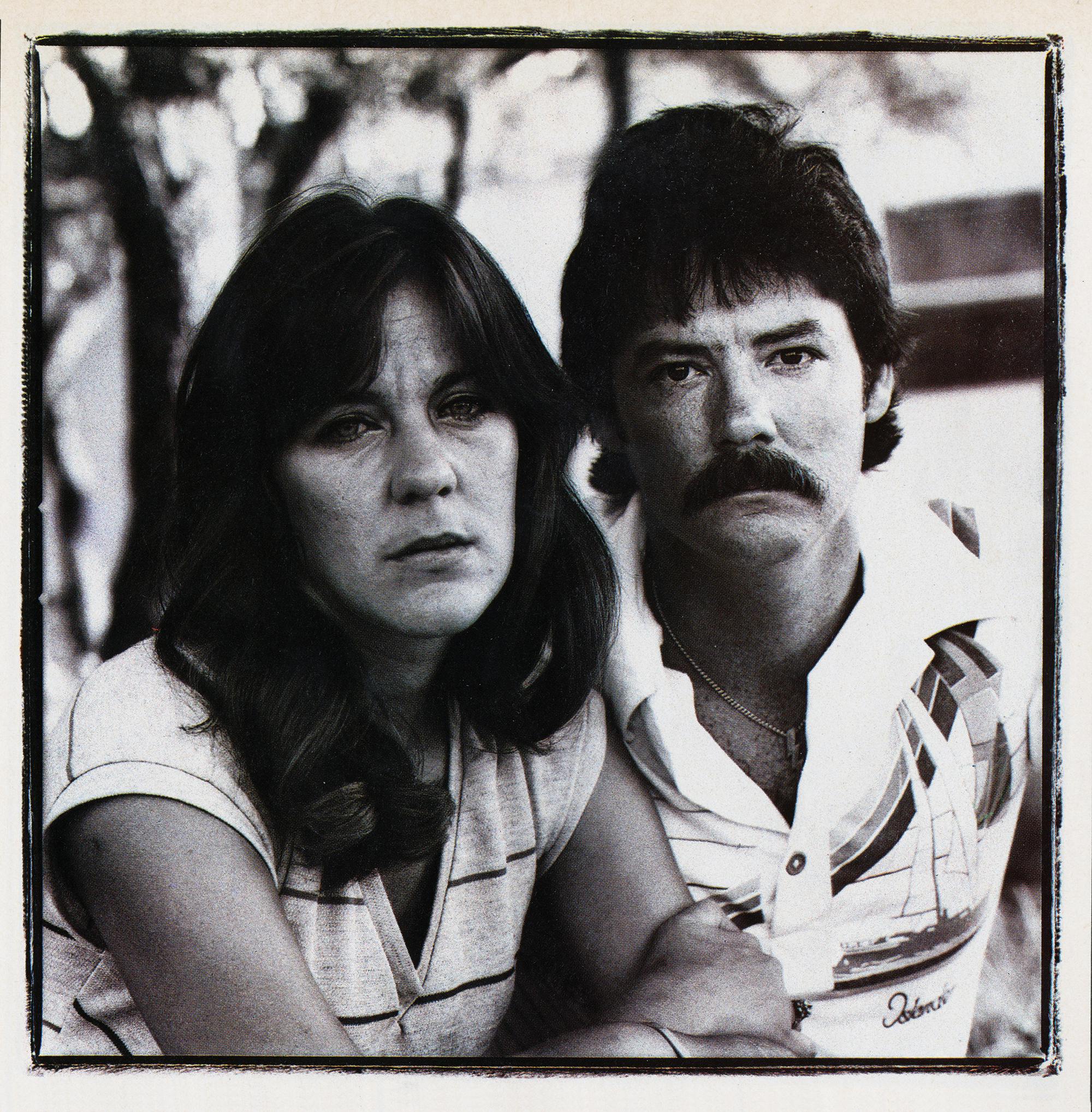

The Dream Girl

Like many parents in and around Kerrville, Petti and Reid McClellan were pleased when they heard that a new pediatrician was coming to town. Here was a chance to take their kids to a real expert, a young woman fresh from training in the most modern medical techniques. “Everybody was real excited about it,” says Petti. “I just had this thing about specialists.” The McClellans, both 28, had met in Llano, where Reid owned the Hi-Line Fishing Lodge on Buchanan Lake (he has since sold it and become an electric line repairman) and Petti spent time at her mother’s weekend home. They were married on May 10, 1980, in an outdoor ceremony. They made an attractive couple: Reid, solidly built with thick black hair and a shaggy moustache; Petti, slender and a bit frail, with a sweet face and a girlish smile. Each already had one child—Reid a son named Shay and Petti a son named Cameron. Now both wanted another child, and both wanted a girl. “From the minute I found out I was pregnant, I started calling it she,” says Petti. “If someone bought me a baby gift for a boy, I’d take it back.”

Chelsea Ann was born at 12:01 p.m. on June 16, 1981. She was about four weeks premature, and the delivery was difficult; the placenta tore early, and Petti bled heavily before she arrived at Sid Peterson Hospital. Shortly after birth, Chelsea showed evidence of hyaline membrane disease, a respiratory problem caused by underdeveloped lungs, usually found in premature children. A helicopter ambulance took her to the Santa Rosa Medical Center in San Antonio, and she was put on a respirator in the neonatal ICU.

At Santa Rosa, Chelsea improved steadily. On July 5, after 21 days in the hospital, she was eating well and breathing on her own, and her weight had climbed to four pounds, six ounces. Her parents took her home. With Chelsea out of the hospital, Petti went to her gynecologist and had herself sterilized by tubal ligation.

On May 6, 1982, Petti brought Chelsea back to the Santa Rosa emergency room. She was feverish and on the previous night had experienced what Petti described to hospital personnel as two “breath-holding” spells. Petti says one occurred when one of Chelsea’s brothers knocked her down; she briefly stopped breathing and turned blue. After dinner, Chelsea began vomiting and lost her breath a second time, Petti says, until she blew air into her daughter’s mouth. Chelsea, then ten months old, remained at Santa Rosa until May 11. She was treated for pneumonia, but an assortment of tests turned up no evidence of seizures or a breathing disorder. “I would just caution the parents to observe her closely,” wrote one doctor who examined her there. “Her growth and development have been amazingly fine for her age, and I don’t think there is any reason to suspect she is going to be slow in the future.”

The McClellans took Chelsea back to their mobile home in Ingram, six miles west of Kerrville, where they had moved by that time, and lavished attention on her. She developed a spoiled child’s temper, but she was attentive and curious. She followed the large world around her closely with her blue eyes, and when someone caught her staring, she would laugh and break into a wide, coy smile. “She was a beautiful kid,” says Genene. “God, she was beautiful.”

Chelsea McClellan: The Beginning

Tuesday, August 24, 1982

Dr. Holland had opened her office on Monday, and Chelsea McClellan was her second patient. Petti says she called in the morning to make an appointment and spoke to Gwen Grantner. Holland says Gwen told her Petti was worried about Chelsea’s “erratic breathing” and that when Chelsea arrived in the waiting room, she had a bluish tint around her mouth. But the McClellans say they never described any breathing problems to Holland, Genene Jones, or Gwen Gartner—then or later. “There wasn’t a damn blue thing about Chelsea,” says Petti, “except her eyes.” She took her daughter to the doctor, she says, because Chelsea had the sniffles. On the patient information form she filled out in Dr. Holland’s waiting room that day, Petti listed the reason for the visit as “bad cold.”

Petti and Chelsea arrived at the clinic about 1 p.m., and Dr. Holland led mother and child to her private office, in the back of the suite. As Holland began to ask Petti about Chelsea’s medical history, the little girl started pulling things off Holland’s desk. “Why don’t you let me take Chelsea and play with her so you can talk?” Genene suggested. She picked the child up and took her out of the office.

The summons came five minutes later: “Dr. Holland, would you come here?” Holland excused herself, closing the door behind her, and walked back to the treatment room to find Chelsea limp on the examining table and Genene fitting an oxygen mask over her face. Genene later said that she had been playing ball with Chelsea in the receptionist’s area and the child had suddenly slumped over. But now there was no time to ask questions: Chelsea wasn’t breathing. Genene began pumping oxygen into her lungs with a respiratory bag, and she and Holland started an IV in her scalp. Chelsea began seizing; Holland ordered 80 milligrams of Dilantin, an anticonvulsant drug. They called the Kerr County Emergency Medical Service (EMS). Chelsea’s mother had no idea what had happened until Holland returned to her private office to tell her. “Your daughter’s just had a seizure,” she said. Holland told Petti to stay put, but she followed the doctor into the hall and looked inside the treatment room as Holland went back in. Chelsea was sprawled on the examining table, Genene hovering over her. “I could see her little legs,” says Petti. “She was laying there, real limp.”

The ambulance arrived at 1:25 p.m., and Genene carried Chelsea into the back of it as an emergency medical technician (EMT) followed along with an IV bottle. Holland joined them, and Petti got in with the driver. They arrived at the Sid Peterson emergency room two minutes later. By that time Chelsea had resumed breathing on her own. She was sent to the ICU and remained at Sid Peterson for nine days, but tests showed nothing to explain the seizure and the respiratory arrest. The McClellans, nonetheless, were deeply grateful. Dr. Holland and the nurse, they believed, had saved Chelsea’s life. “We worshipped the ground these people walked on,” says Reid. Petti began telling her friends about the new pediatrician. “I went all over town: ‘Take your kid to Dr. Holland; she is the best thing since canned beer.’”

Brandy Lee Benites

Friday, August 27

Nelda and Gabriel Benites were worried. Brandy Lee, their one-month-old daughter, had blood in her stools and diarrhea that persisted for two days. They took her to the emergency room at Sid Peterson Hospital, but the staff there sent them to the new pediatrician in town. They arrived at Kathy Holland’s clinic late in the morning. The doctor and her nurse took Brandy’s history, asked Mr. and Mrs. Benites to remain in the waiting area, and then carried the child back to the treatment room. Mrs. Benites soon saw Genene Jones rushing back and forth. Then Dr. Holland came out and told them their daughter had stopped breathing.

Holland says that Brandy was gray and lethargic when she arrived in the office and that the baby was given only oxygen before she stopped breathing and had a seizure. Holland’s office called EMS at 11:37 a.m. After half an hour at Sid Peterson Hospital, Holland told Brandy’s parents that she wanted to transfer their daughter to Santa Rosa Hospital in San Antonio. The ambulance set out about 3 p.m. with Genene, an EMT, and a respiratory therapist in the back and Kathy Holland following in a car. Holland explained to Mr. and Mrs. Benites that she got carsick in an ambulance.

As the ambulance raced toward Santa Rosa, Genene began barking orders to the EMT and pleading with the tiny patient, “Please, baby, don’t die! C’mon! C’mon!” The EMT thought the nurse strange. “She was getting out of control,” he said later. “She turned the whole situation into ‘the world’s falling in.’ The baby was in bad shape, but calm, collected movements are better than going crazy.” During the trip Brandy’s pulse suddenly grew faint. “Stop the ambulance!” Genene hollered. The car pulled over to the side of the road, Holland rushed in, and they revived the baby. It had been a close call. Holland climbed back into her own car, and the procession went on its way again.

Brandy Benites remained at Santa Rosa for six days. Doctors were unable to detect what had caused her emergency.

Christopher Parker

Monday, August 30

Mary Ann Parker, a registered nurse at a Kerrville convalescent home, brought her baby boy to Dr. Holland’s office at about 10 a.m. Christopher, four months old, had a condition called stridor—raspy breathing caused by constricted air passages. Genene came into the waiting room, looked Chris over, and pointed out that his feet seemed a bit blue. She took the baby back into the treatment area while Mrs. Parker waited outside.

Then Kathy Holland came out to talk to her. “I told the mother that I felt that we should have him in the hospital so that I could evaluate his stridor and decide what the next step was,” Holland said in a court deposition. “And I told her that I wanted to transport him by ambulance in case anything unexpected happened.” Holland said the baby never stopped breathing or had a seizure in the office; the EMTs, called to the office at 10:21 a.m., were told he had “respiratory distress.” The ambulance took Chris, accompanied by his mother and Genene, to the emergency room. Genene rushed the child in and hovered over him as though expecting a disaster. The hospital nurses were puzzled; the baby had breathing problems but seemed to be stable, hardly even an emergency case. Mrs. Parker watched anxiously from close by. “I hope the baby doesn’t go into arrest while we’re waiting,” said Genene.

Shortly after Chris Parker arrived in the emergency room, seven-year-old Jimmy Pearson was brought in. Jimmy had an often-fatal heart defect called Tetralogy of Fallot and a hereditary condition that limits bone growth. He weighed only 21 pounds, and doctors had long predicted his demise. On this day Jimmy had gone into seizures, and he was taken to the emergency room by ambulance. The nurses there called Holland over and asked her to look at him. He was semiconscious and blue from lack of oxygen, and he was frothing with phlegm. Holland consulted by phone with the two doctors who had been treating Jimmy in San Antonio and then told his mother, Mary Ellen Pearson, that they needed to transport him to Santa Rosa. Holland called Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio and arranged for a transfer by Army helicopter ambulance, a Military Assistance to Safety and Traffic unity from the 507th Medical Company.

When paramedics David Maywhort and Gabriel Garcia arrived at the helipad outside the Kerrville Veterans Administration Hospital and were taken to Sid Peterson, Dr. Holland asked them if they could also transport Chris Parker to Santa Rosa. Chris had in the meantime been transferred up to the ICU, and Maywhort went up to check on his condition. He looked fine. Maywhort wondered why Chris needed to be transferred at all, but the medics agreed to take both children. The ambulance shuttled the patients, paramedics, and Genene out to the helipad. It would be a wild ride.

Everything was fine for fifteen minutes, according to the paramedics’ descriptions of the flight to investigators. Then Genene got out of her seat and began looking at Jimmy Pearson. She shouted and gestured to the paramedics; she seemed to think Jimmy was seizing. The paramedics looked at the boy. His condition didn’t appear to have changed. Genene took out a stethoscope and placed it on Jimmy’s chest. The paramedics looked at one another. They knew it was impossible to hear a heartbeat over the din of the helicopter. They shouted at her, but Genene waved back. She was saying she could hear. What was going on? She began gesturing again, shouting that the patient was going bad, that his heartbeat was irregular. Garcia checked the monitor; he saw no change. Maywhort was inches from Jimmy Pearson. He looked closely at the child; his condition seemed the same as when they’d taken off. But Genene was getting out a syringe. She was about to inject Jimmy with something through the IV line. Maywhort waved at her to stop, but she went ahead anyway. “Sir, mark time!” Maywhort radioed the pilot. “She’s pushing medication!” A few moments passed. Then the monitor started showing heartbeat irregularities. Jimmy was turning blue. The paramedics looked at his chest; he had stopped breathing. They checked for a pulse in his neck. There was none.