This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

I wondered if I might be dead. My body felt heavy and lifeless. My spirit, I thought, might be in some sort of holding place, on the way from the life I had known to a new realm. I was afraid, frightened that the bull would be there waiting for me. From somewhere beyond the veil of drugs that dimmed my consciousness, his eye stared back at me.

The tiny room, an intensive-care unit, was deathly quiet. The only sound I could hear was that of my own breathing. A young Mexican nurse sat near the foot of my bed, watching me silently. From time to time she would rise, come to the side of my bed, gently lift my arm, and take my blood pressure. Then she would return to her chair and resume her watch.

A man on a stretcher was rolled into the room by several doctors in white coats. His head was heavily bandaged, and he groaned in deep, painful sighs. They moved the man from the stretcher to the bed beside me, then left the room. I watched the man as he lay in the near darkness, groaning. And then he stopped. He was perfectly silent.

The nurse left and returned with the doctors. They examined the man, then rolled him away. As they left, I tried to raise myself in the bed to see where they were taking him, but I had no strength. My arms were terribly heavy, and my chest throbbed with a dull pain when I tried to move. I looked at the nurse.

“Where did they take that man? Is he going to be all right?”

The nurse answered without emotion: “He’s dead, señor. The bull threw him, and he landed on his head. The doctors couldn’t save him.”

“What about me? Am I going to die?”

“I don’t know.”

I closed my eyes. Below me I felt a bottomless void opening. Frightened, I opened my eyes, and the void went away. But the eye of the bull reappeared. It rolled from side to side in its deep, slippery socket, searching the room for me.

I closed my eyes again and it was that September day in 1989, the first time I ran with the bulls.

It was noon when a huge black truck with seven red doors pulled slowly into place. Its air brakes hissed, and the people cheered as it lurched and swayed. As it stopped in the shadow of the church tower, six men danced on top of it, pointing to the red doors and screaming to their friends in the street below.

Twenty thousand people had gathered in the zócalo of San Miguel de Allende to watch the running of the bulls and participate in it, and I had come to photograph the spectacle. People filled the streets as far as I could see in every direction. They hung from lampposts and street signs, covered the rooftops, and peered from the windows and doorways. They had even climbed onto the huge statue of Fray Juan San Miguel in front of the church, transforming it into a small mountain of humanity.

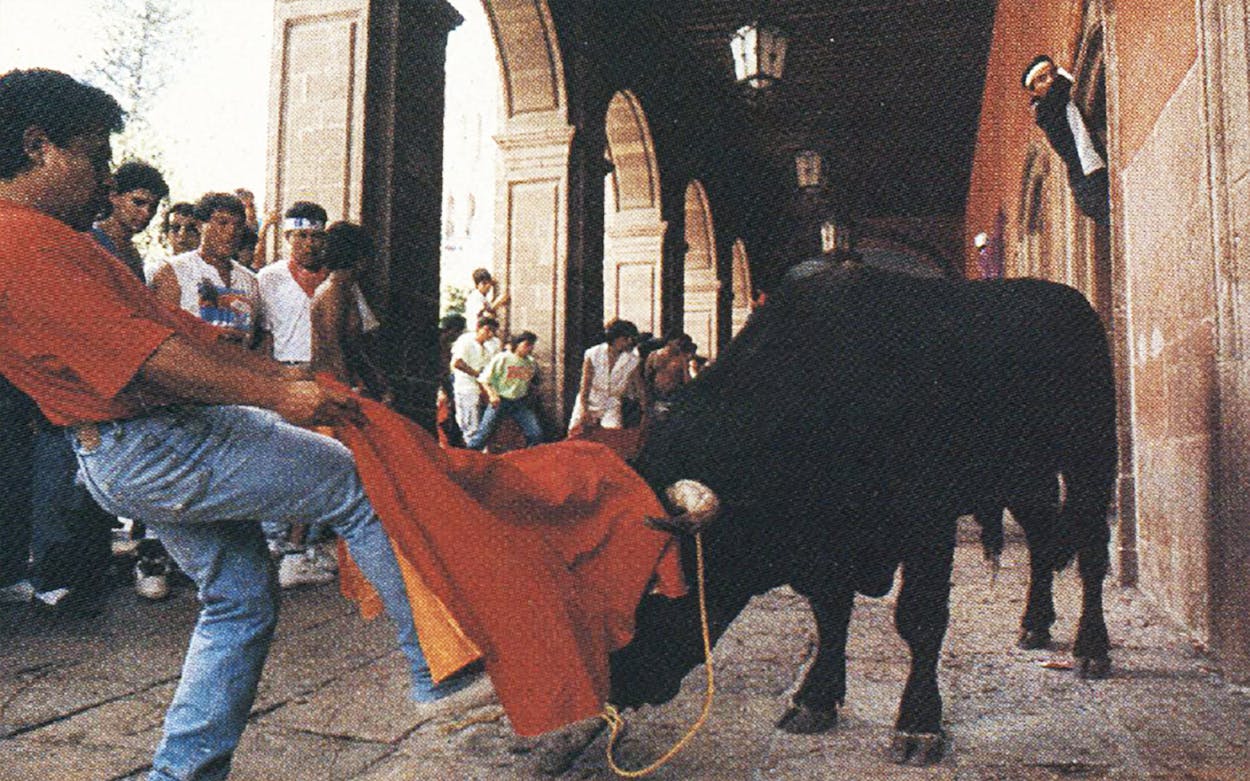

They had been arriving since dawn, many of them drinking, singing, and dancing through the morning hours, and now the event they awaited was about to begin. When the truck stopped, the crowd surrounded it, pressing close to it on all sides. Young men, many of them dressed in white shirts with red bandannas around their necks, unfurled red capes and began to practice the classic moves of a matador. Moving toward the truck, they chanted in unison, “Toro! Toro! Toro!” On top of the truck, the men jumped up and down. I could hear the bulls inside, smashing their horns against the steel doors.

I looked for a place to hide. I knew that soon, one by one, the red doors would be lifted and the bulls would be released into the street. The only refuge was in the crowd itself. With thousands of people on the streets, the odds of being actually hit or trampled by the bulls were relatively low. But one look at the doors now being pounded and dented by the beasts inside and the thought of such odds was little consolation. The panic of the crowd would soon create a danger greater than that of the bulls.

On top of the truck a man dropped a steel rod into the first red door and began to lift it. Another man looked into the stall and called to the crowd, “El Negro! Viene El Negro!”

As the door was lifted, I made an impulsive, last-minute decision to leave the crowd and move to the right side of the ramp leading from the truck to the ground. I reasoned that the bull, as he exited the truck almost six feet above the street, would go down the ramp as intended. In the unlikely event that he jumped off, I could duck underneath the ramp for safety. Besides, the area next to it was a perfect vantage point from which to photograph the bull’s charge. I checked my camera settings, selected a fast shutter speed, and looked up the ramp.

Now the first red door was up. I was looking straight into the eyes of the black bull. Only twelve feet from me, he stood motionless for an instant, as though mesmerized. A chill passed through my body. I brought my camera up. Then, in a flash, in one powerful leap, he shot forward.

He seemed to barely touch the ramp as he flew past me, only a foot or two from my camera. I shot three frames before he hit the cobblestones, three more as he slipped, rolled on the pavement, regained his feet, then charged, chopping and hooking furiously with his horns.

People scattered in every direction. Caught on the bull’s horns, some were flipped over his side or his back. Most of the rest dodged, faked, or sidestepped his deadly lunges. Several men seemed absurdly fearless, dangling their capes in front of the bull as he whirled and attacked.

Soon I could no longer see the bull himself, only what looked like a human tornado, a swarm of men spinning around an unseen center that disappeared down the street. As I watched El Negro disappear, I heard the second bull announced. He was called Red Eye.

“Ojo Rojo! ” yelled a man on top of the truck. And the crowd chanted back, “Ojo Rojo! Ojo Rojo! Ojo Rojo!” stamping their feet and twirling their capes.

As the door was lifted to release the second bull, the danger and the irony of the situation struck me. What was I doing here, I asked myself, a grown man of 47 years, with a wife and family, a mortgage and life insurance, standing in the street of a Mexican town awaiting the charge of a wild bull? But my mind was not in control of the situation. My heart was racing. I was feeling the rush of hormones I had never known. I was grinning from ear to ear. I was talking to myself, giggling out loud as the second door came up. A few feet away from me at the top of the ramp stood Ojo Rojo. Unlike the bull before him, he did not hesitate. As soon as the door was up, he charged.

He too hit the pavement and slipped, but he did not go down. And this time the crowd was closer to the bull, a bit less cautious. The huge red bull spun one hundred and eighty degrees and charged back toward the truck, toward me. I ducked under the ramp, jostling with a dozen other men for safety. The bull caught a man in front of me, his horn ripping at the man’s left arm. Blood spewed into the air. Then the bull spun again and disappeared into the crowd.

The man who had been gored lay groaning in pain, his blood forming a dark red puddle in the street. People had rushed to his side, and one man fashioned a tourniquet from his red bandanna. From above and behind me I heard “Güero! Güero!” and realized that there would be no time-outs for injuries. The third bull was being announced. The door was lifted and a light gray animal with one broken horn stared out at us. Then I heard shouting behind me and saw that El Negro had returned.

The entire event seemed insanely dangerous, and all at once I remembered the words of a young Mexican man who had approached me before the pamplonada began: “You want to dance with the devil, señor? ” He had asked the question, I felt, as a dare, a challenge to a naive gringo who probably had no idea what he was getting into. “Yes,” I had said, “I’d like to dance with the devil, and I’d like to get a few good pictures of him as well.” The man had smiled as he shook my hand and looked me in the eye: “Cuidado, señor—take care. The devil, I think, does not like to have his picture taken.”

Two hours after Güero had been released and all seven bulls were in the streets, I looked at my watch and was amazed to see how much time had passed. Dozens of people had been injured, nine of them badly enough to be hospitalized. But I also noticed that the tables had turned. The powerful, swift bulls, objects of fear at the start, now hung their heads in exhaustion, and the crowds pushed closer.

Just west of the church, I approached a group of men who had surrounded Güero. His eyes gleamed with rage as he turned his head slowly, scanning the crowd around him. He was gasping for breath, and blood trickled from his mouth. The men were bolder now in the face of the exhausted beast. One darted toward the creature and jerked at his tail.

Another man jumped out and kicked the bull in the side of the head. Guero took several kicks from the man before he suddenly reeled to his left and charged directly at me. With a building behind me, there was nowhere to run. I could only turn my face and body against the wall. When the bull charged past, his horns grazed my lower back, and I felt his enormous power.

As the bulls became even more exhausted, the continuing drama took on a comic form. One young man ran forward, stroked the horn of a bull in mock affection, then kissed it. Another man rested his elbow on the bull’s head, crossed his legs, and assumed the casual pose of a man making a telephone call.

The jeering and taunting of the bulls went on for another hour or more. Then the animals were finally roped and pulled back to the truck. As they went by I saw a Mexican boy, perhaps twelve years old, reach out and run his hand across a long, deep gash in one animal’s leg. Then he wiped his hand, dripping with the bull’s blood, across his face, over his forehead, and through his hair. He turned and smiled at me for an instant, a devilish glint in his eyes. Then he turned and ran into the crowd.

The manly fascination with bulls has been recorded throughout history. Wherever wild bulls have existed, they have been hunted and fought. Forty centuries ago, men confronted them in Crete, later in Greece, and then, according to Pliny, in Julius Caesar’s Rome. History suggests that the Romans were the ones who organized bullfighting in Spain, and by the beginning of the Middle Ages, bulls were being fought there in two quite different ways.

Among the nobility there developed a graceful equestrian spectacle that evolved into today’s corrida de toros, or bullfight. At least since the thirteenth century, bullfights have been organized by the sporting noblemen of Spanish communities, primarily to celebrate festival days.

But also in the Middle Ages a savage, lawless pastime evolved, in which bulls were tracked and hunted by peasants. The running of the bulls in Pamplona must have descended from this ancient sport. I have read that in Pamplona, men still believe that anyone who can run with the bulls, especially anyone who can touch them as they run, can draw power and virility from them.

What I witnessed in San Miguel de Allende was a uniquely Mexican adaptation of that famous event. It was no coincidence that the pamplonada of San Miguel took place during the week-long fiesta for El Día de San Miguel—Saint Michael’s Day—because it was Michael the Archangel who had faced the biblical dragon and battled him.

The decade-old pamplonada of San Miguel was not only an extension of that ancient secular tradition, but a uniquely Mexican drama as well. It was a real-life pageant with religious overtones, a mythic ordeal in which every man had the opportunity to pit himself against the beast. At the same time, it was the quintessential fiesta experience, a “dance with the devil”—a celebration of life and a flirtation with death.

As I might have expected, when I printed my photographs, they were not up to my memory of what happened. I had a few good pictures, but so much of what I had experienced was not captured.

Especially, I regretted that I had not recorded that brief instant before his charge when I looked into the dead black eyes of the first bull. It was a chilling, frightening memory. The most curious memory, though, one that I was at a loss to explain, was my euphoria. Running through the streets, bulls all around me, the crowd surging, dancing, screaming, I had been ecstatic. The entire experience had been one of the most intense of my life. I could hardly wait to tell my wife and friends about it, to print all my photographs, and—most of all—to do it again.

So, when a big red truck pulled into the zócalo the following year, I was there. The crowd seemed even bigger than in 1989. By eight in the morning the streets were filled with people, and I was instructing a young Mexican man I had hired to operate a camera from atop the wall around the church. From that high vantage point he could take photographs to complement those I would take down in the streets.

Knowing the general plan of the pamplonada, I scouted the center of town for interesting areas to shoot once the bulls were released. What I did not know was that there had been a heated debate in San Miguel after the last pamplonada. The mayor of the town had come under considerable pressure from two groups. The first included merchants and city officials who demanded that the event be canceled because of the rowdiness and destruction it caused; the second was composed of those who let the mayor know that there would be a running of the bulls, one way or another.

A standoff between the two factions had ensued for a couple of days, and then the mayor conceded. The pamplonada, he announced, would be run as usual, and he promised better crowd control, less drinking, particularly on the part of minors, and improved medical facilities. It was good that these changes were provided, too, because when the first bull hit the street at noon on Saturday, it was a different kind of animal from those I had seen the year before.

I had again taken a position to the side of the ramp. As the bull charged past me, his head down low, fire in his eyes, he gave a horrible snorting, growling noise. He was huge, more than six hundred pounds, someone estimated, but he was also quick. When he hit the street, he immediately spun to his left and hooked a man on his horns, lifting him in the air and throwing him straight ahead. Then he was on the man. By the time the bull had been distracted, the street was splattered with blood.

I was horrified. The bull’s fierce and devastating charge was more frightening than anything I had seen the year before. On the other hand, I had shot twelve frames as he came down the ramp and attacked the unfortunate man, and I thought I might have some good photographs. I also noticed a medical emergency tent and ambulances waiting at several points outside the barricades. I had not seen an emergency tent the year before.

Two hours after the pamplonada began, several of the bulls became trapped behind a colonnade to the west of the zócalo. Exhausted, they had backed into a covered walkway behind the giant columns of a bank office. I watched the crowd tease them, and I was struck by how utterly unpredictable the beasts were. A man could be directly in front of one bull, shouting in his face and waving a red cape. Then, with no warning at all, the bull would spin and charge at someone else. The animals were truly like death itself. They attacked when least expected, taking those who might seem the least likely targets.

I was walking along, musing on that thought, when I came on three men who were facing an exhausted bull from perhaps eight feet away. The bull’s head was down and his tongue was out. His glazed eyes seemed focused in the distance. The man in front of the bull was waving a cape at him and jumping forward, stamping his foot.

I stood to the right of the man with the cape, trying to frame a picture. It was an amusing scene, with men hanging from window bars behind the bull. Then, trying for a better shot, I went down on one knee. What happened next I can only piece together from fragments of memory, from my film, and from what people told me later.

In the contact sheet of that roll, frame number seventeen is taken from perhaps twelve feet back and shows the man with the cape facing the bull. In the next frame, the camera is closer to the bull, perhaps eight feet, and lower. In the next two frames, the man is still dangling his cape in front of the animal’s face. In frame twenty, the man steps up and kicks the bull in the head.

I recall vaguely, as though it could have been something I dreamed, looking the bull in the eye through the viewfinder of the camera. The bull’s black eye looked back at me impassively, and at some point I must have become aware that the bull was going to charge.

Next, I remember running, bumping into people, falling in the street. The contact sheet has a blurred frame, shot at the sky, showing a building on the right and a dark, undefined shape on the left. I must have triggered the camera as I fell.

Then I can recall, but only dimly, the sensation of pain in my back, of being lifted and thrown, of trying to get out of danger, of more pain in my backside, and a kind of fuzzy awareness that the bull was after me again and then that he was on me and no one was getting him off. I tried to pull myself under the barricade at the side of the street. There was just enough space to go under, but dozens of human feet were in the way, and there was no way to get through. And then more pain.

Someone tried to help me to my feet, but I could not stand up. People in the crowd gasped when they saw the blood pouring down the leg of my jeans. I was working hard just to breathe, and in the right side of my chest I felt a terrible, heavy pain. Someone helped me to the ambulance, and I thought for the first time that I could be dying. I have heard that at such times one’s life flashes before one’s eyes, but only two thoughts entered my mind.

First, I thought of the additional life insurance I had bought only a month before, and I congratulated myself. Then, I remembered the last play of the championship game of the Little League team I had managed that past spring. My Wildcats had come from behind and taken the lead by one run. When our opponents came to bat in the bottom of the last inning, my son, Michael, was our pitcher. He struck out two batters, but two reached base. Then, with two outs and two strikes on the next batter, Michael wound up and delivered the last pitch of the game.

A nurse in the Mexican ambulance squeezed my hand and told me to lie still and flat. As I struggled to breathe, I could see Michael’s pitch, how perfect it was—a fastball outside at the knees. Then I saw the batter’s swing, the ball hit to center field, the runners moving, the center fielder coming in to make the catch . . . and the ball sailing over his head.

We had lost the game, and I felt like crying. Damn, I thought, we had played so well and we had come so close. I was still thinking of the Wildcats’ last play, of those kids coming off the field wanting to cry too but holding back the tears, when the men took me out of the ambulance and rolled me into the little hospital in San Miguel. A doctor began cutting off my clothes.

“How badly am I hurt?” I asked the doctor. “Am I going to live?”

“I don’t know yet, señor,” the doctor replied, turning me on my side, “but I can tell you for sure that the bull—how do you say in English—well, he has given you a new ass. Now we will find out how bad he has hurt you.”

Three weeks later I checked out of the hospital in Houston. My collapsed lung, four fractured ribs, and two gore wounds in the right buttock—one more than nine inches deep—were healing. I had received excellent medical care in both hospitals. Life-threatening infections had developed, as is often the case with gorings, but the doctors had drained the wounds and antibiotics were doing the rest. Barring the remote possibility of a bone infection, I was going to recover.

During my recuperation, many friends came to visit me in the hospital, among them my Episcopal priest. He and I talked at length about the running of the bulls, about its religious context in Mexico, about my euphoric experience in the streets of San Miguel, and about the haunting image of the eye of the bull. “Some people would simply say you were crazy,” my priest pointed out, “that only an idiot would put himself in the street with bulls that way. You know that?”

Yes, I knew that. But I knew some other things as well, things I could probably never explain. I knew now why the event at Pamplona had drawn men for centuries. They understood that running with the bulls puts one in touch with primal forces, not the least of which are forces within us.

I am getting older, and I know that the time will come when my strength will leave me. That is a fact that will not change. And it is a fact for which I may grieve more than I now realize. But for a couple of hours at the pamplonada, I was young again. Ecstatic, bubbling over with laughter, I had never felt more alive than when the bulls were charging all around me.

It seems so obvious and so profoundly true now, the tenet of Mexican philosophy that one must stay close to death in order to be fully alive. The fact that I had almost died seemed incidental. I had danced with the devil. I had looked him in the eye. I had felt his terrible power and taken his warning. That could not be photographed, perhaps could not be described, and certainly could not be forgotten.

Geoff Winningham is a photographer who lives in Houston.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Mexico

- Longreads