This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Think Texas, and you think success: ranching empires and gushers and boom towns bursting at the seams. Well, Texas has had its successes, but it’s had some spectacular failures as well. In fact, failures, not successes, made Texas. After all, not the Spanish or the French or the Mexicans, not the Republic or even the Confederacy, managed to hang on to Texas. People flocked here because they couldn’t make a go of it elsewhere, but what happened when they arrived? Wells ran dry, grass gave out, cities gave up the ghost. But such setbacks only encouraged them to keep on searching for something bigger and better, and today Texans are still gambling and losing and gambling again. So perhaps we owe a debt to the duds, flops, botches, and bungles that made our state what it is today; we can even be proud of them. Or failing that, at least we can profit from past mistakes.

False Starts

With all due respect to the Daughters of the Republic of Texas, the Battle of the Alamo was clearly a failure. There was no way that 187 men could fend off Santa Anna’s hordes, who numbered some 4000. The Mission San Antonio de Valero was inadequate as a fort; William B. Travis, a notorious hothead, was inadequate as a leader.

Not only was the actual battle a washout but 124 years later the 1960 film reenactment, The Alamo, was a disaster too. John Wayne played Davy Crockett and also made his directorial debut in this long, rambling, boring box office bomb.

In 1540, following reports from Cabeza de Vaca and other Spanish explorers that a wondrous, shining land existed somewhere in the New World, Coronado set off with three hundred soldiers to track down the legendary Seven Cities of Cibola. He was accompanied by a mendacious friar who claimed to have personally seen silver streets and turquoise-inlaid doors.

Traipsing along the Rio Grande, Coronado finally came upon the mythic cities, which turned out to be merely a cluster of Zuni Indian pueblos. He was disappointed, but not for long: ever the dupe, he next swallowed the tale of the Gran Quivira, an equally fabulous city built of gold and jewels. Heading north across the Texas Panhandle, Coronado made it as far as central Kansas before learning that Quivira was nothing more than a ragtag village of Wichita tepees. He returned to Mexico to face widespread ridicule and died in disgrace.

Another hapless explorer was La Salle, whose expedition 145 years later was an even greater dud. First he overshot the mouth of the Mississippi River, his intended destination; then, once in Texas waters, he lost two ships in Matagorda Bay. Venturing into the unfamiliar territory of Texas, La Salle was murdered by one of his own men; all but a few of his followers either disappeared or were massacred by Karankawas shortly afterward.

Mistakes as Big as Texas

In 1845, on Texas’ admission to the Union, Congress passed a resolution that allowed Texas to divide itself into five states if it so chose. There have been no less than sixteen unsuccessful attempts—the first in 1850 and the most recent in 1969—to create various mini-Texases to be known by such names as San Jacinto, Lincoln, Franklin, Jefferson, and Matagorda. Native Texan and former U.S. vice president John Nance Garner was the most famous supporter of divisionism (he, of course, also backed such hopeless endeavors as naming the cactus blossom the state flower).

But the late state senator V. E. “Red” Berry of San Antonio was the most colorful divisionist. In 1969, irked by the clockwork regularity with which his pari-mutuel betting bills failed in the Legislature, Berry introduced a proposition to draw a line from Orange to El Paso and create a new, fun-loving state of South Texas, which would promptly legalize horse racing. Under Berry’s plan, San Antonio would have become the capital of South Texas and the Hemisfair grounds would have served as the state office complex, with the governor of the new state ensconced in the rotating restaurant of the Tower of the Americas. Berry’s great idea went the way of his parimutuel bills before it.

A black day in Texas history: January 3, 1959, when Alaska entered the Union as the 49th state, dooming to failure our long-savored and ardently publicized status as the biggest of the states, ruining several perfectly good jokes, and requiring immediate alteration of the “largest and grandest” line in the state song.

The state song, of course, is a failure in and of itself. But its unquestionable dullness is understandable if you know that (1) the quest for an official anthem resulted in a statewide contest in 1924, which (2) an Englishman won. The first time “Texas, Our Texas” was scheduled to be performed at a state event, the band balked and played the governor’s campaign song instead.

In 1974, after a committee had spent eight months drafting a new version of the 63,000-word, 233-amendment state constitution, 181 legislators met in Austin for the first constitutional convention since 1875. But after spending seven months and $5 million, the legislators were unable—by three votes—to get the two-thirds majority needed to approve the new constitution before July 30, at which time it was officially dead.

The Texas Navy, organized in 1836, never had more than a dozen ships, and most of them were lost at sea, left to rot, or sold off to pay repair bills. When the U.S. annexed Texas, only four of the vessels remained, three of which were declared unfit for use.

In 1860, the Texas Legislature had a bright idea: why not use the North Fork of the Red River as the state boundary instead of the South Fork, since that meant Texas would get more land? Accordingly, the state moved the boundary line, christened the new land Greer County, imported settlers and cattle, and threw in a few churches and schools for good measure.

Fortunately, the Civil War happened along just then and prevented the federal government from noticing that its territory had just been rustled. What with one thing and another, the feds didn’t get around to challenging Texas’ claim till 1895. Then, as in most of its tussles with Uncle Sam, Texas lost. The Supreme Court ruled that the South Fork of the river was the boundary—in fact, the south bank of the South Fork. The worst part of it was that the Legislature’s great idea had turned into—good heavens!—Oklahoma.

Winners Are Losers Too

Sedco, Governor Bill Clements’s drilling company, provided the rig used to drill Ixtoc I, the Mexican oil well off the Yucatán peninsula that blew out on June 3, 1979, and spewed more than three billion barrels of crude into the Gulf—and it eventually drifted onto Texas beaches. It took nine months for workers to cap Ixtoc I, which lives in infamy as the cause of the world’s worst oil spill.

Throughout the fifties, millionaire Houstonians George Kirksey and Craig F. Cullinan, Jr., tried—without success—to buy almost every major league team then in existence. In 1959, plans for a third baseball league, the Continental League, got under way, and the eager Kirksey and Cullinan hurriedly formed the Houston Sports Association as a starting point for organizing a Houston team. Then the National and American leagues decided to expand to block the creation of the third league, and Kirksey and Cullinan lost again.

One of native Texan Howard Hughes’s earliest business ventures was his purchase of the faltering RKO Pictures Corporation in 1948, but for once his golden touch failed him; even he couldn’t turn it around. He released such fare as Double Dynamite and Son of Sinbad under the RKO banner before he grew restless and sold the company in 1955.

In 1971, newspaper headlines across the state trumpeted the breaking of the Sharpstown scandal. The federal Securities and Exchange Commission filed a civil suit charging that Houston financier Frank W. Sharp and other officials of the National Bankers Life Insurance Company had manipulated the corporation’s stock to fatten the wallets of various Texas political leaders, including Governor Preston Smith, Speaker Gus Mutscher, two state legislators, and the chairman of the state Democratic party. To return the favor, the suit said, Mutscher had ensured that legislation favorable to Sharp passed the House.

The uproar led to Mutscher and two of his aides’ being tried and convicted of conspiring to accept a bribe. But the scandal didn’t stop with the guilty: the state’s voters took over, and Smith failed to win a third term. Whiz kid Ben Barnes, the 33-year-old lieutenant governor who competed with Smith for the gubernatorial seat, also lost the race, tainted by the fallout from the scandal.

FACT:

3635 students applies to enter UT-Austin in the fall of 1980 were not accepted.

Despite various and sundry political defeats and embarrassments during his career, Lyndon Johnson’s biggest failure was the Viet Nam War. Enough said.

During Lyndon B. Johnson’s tenure as president, the White House commissioned artist Peter Hurd to paint the chief executive’s official state portrait. Hurd presented LBJ with the painting in 1966—only to have the president ban it from the White House, declaring it the ugliest thing he ever saw.

H. L. Hunt’s first novel, Alpaca, concerned an idealistic young Latin American who set out to discover the perfect constitution and thus save his country, Alpaca, from an evil dictator. As H. L. would have it, the perfect constitution is one that entitles you to more votes the more taxes you pay. Alpaca was not a runaway best-seller; neither was its sequel, Alpaca Revisited. Luckily, Hunt had enough money to publish them himself.

When Nelson Bunker Hunt, son of H. L., and his brother William Herbert began investing in silver in the seventies, they were seeking an asset to replace oil, a resource whose days seemed numbered. The Hunts began accumulating and storing silver as well as dealing in silver futures, and soon they had an enormous stockpile.

Naturally, with such heavy dealings going on, the price of silver shot up: in January 1980 it cost $50 an ounce. The exchanges then imposed restrictions on silver buying, and the price began to fall. On March 27, 1980, after the Hunts revealed that they were unable to meet a $135 million margin call, the market collapsed; silver dropped to a measly $10.80 an ounce. The Hunts at that time owned about 150 million ounces of silver. Because they had purchased it at various prices, their exact losses are unknown but, at the very least, reached $1 billion.

In 1960, Lamar Hunt, another of H. L.’s sons, helped to organize the American Football League and obtained the charter franchise for the Dallas team, which he named the Dallas Texans. That year the AFL had its first season, and the turnout was pathetically scant; Lamar lost half a million dollars. Not until 1963, when he moved his team to Kansas City and renamed it the Chiefs, did he start to make money. Undaunted by one sports failure, Lamar promptly bought a soccer franchise, the Dallas Tornado, which distinguished itself in 1968, during its second season, by blowing 21 games in a row—a losing streak unequaled in the annals of soccer.

In 1977 Bunker Hunt made headlines by announcing that he would raise $1 billion for Here’s Life, a branch of Campus Crusade for Christ, and he promptly backed up his promise by pledging $10 million of his own money. He also asked selected power-mongers and millionaires to donate $1 million apiece toward his worthy cause. He discovered that other people were not as rich or as religious as he: Bunker has thus far achieved only 20 per cent of his goal.

John Connally spent $11 million trying to get the Republican nomination for president in 1980. But after a fourteen-month campaign he ended up with exactly one delegate to the national convention—and she wasn’t even a Texan.

It Seemed Like a Good Idea at the Time

The foremost federal boondoggle of 1855 was, without a doubt, the importing of camels into Texas. Congress appropriated $30,000 to bring in the beasts for use as military pack animals, and a year later 34 camels landed at the port of Indianola and were marched to San Antonio, with a brief stop to allow a Texas lady to knit President Franklin Pierce a pair of memorably odorous camel’s hair socks. But when the camels arrived at their new home the troops’ horses wouldn’t walk a mile with them—and neither would most of the men. With the advent of the Civil War, the military’s enthusiasm for the idea fizzled. Most of the camels were let loose in the West Texas desert, where they were still alarming tipsy prospectors as late as 1891.

The federal government spent $400 million on IH 27, a four-lane highway linking Amarillo and Lubbock, to handle the increasingly heavy traffic that was expected to materialize between those two cities. It didn’t.

In 1977 the National Endowment for the Arts gave an artist $6025 to film mile-long rolls of colored crepe paper as they were flung from an airplane flying over El Paso. The citizens of that fair city couldn’t have cared less—and who can blame them?

Easy Acts to Follow

These native Texans did the home folks proud when they made it to Hollywood and the silver screen. But nowadays they’re remembered—if remembered at all—as talents that were mediocre at best.

Jack Buetel of Dallas made his film debut in Howard Hughes’s 1943 film The Outlaw, in which he was unceasingly upstaged by Jane Russell’s bustline. He couldn’t act, anyway, and Hughes never let him star in another picture.

Austin native Zachary Scott appeared in some solid movies in his day—including Mildred Pierce, for which his leading lady, Joan Crawford, won an Oscar—but he just wasn’t star material. By the late forties and early fifties he was reduced to making lamentable films like Born to Be Bad, Guilty Bystander, and Let’s Make It Legal.

John Boles, born in Greenville, played second fiddle to Shirley Temple in such thirties gems as Curly Top, The Littlest Rebel, and Stand Up and Cheer.

John Arledge, from Crockett, played a dying soldier in Gone With the Wind.

Whip Wilson, from Pecos, was a rodeo star turned movie star. He had his own series of second-rate westerns, including Haunted Trails, Crashing Thru, and Shadows of the West.

Larry Buchanan of Dallas was a bit actor who turned to producing and directing, starting with a western called Grubstake in 1952. Some of his movies, like Mars Needs Women and Mistress of the Apes, were predestined to become Saturday morning post-cartoon fare; others were B-movies of unrivaled pulpiness, such as High Yellow and Free, White, and 21.

Some other little-known Texas actors and their duds:

Joyce Reynolds, San Antonio, The Constant Nymph, Wallflower.

Henry Roquemore, Marshall, Stocks and Blondes, Exile Express.

Nancy Gates, Dallas, The Tuttles of Tahiti, Hell’s Half Acre.

Reed Hadley, Petrolia, Female Fugitive, Juke Box Jenny, It Shouldn’t Happen to a Dog.

In the thirties Hollywood studios billed western actors Bob Steele of Pendleton, Oregon, and Kermit Maynard of Venvay, Indiana, as native Texans to promote their tough-guy image—but even with the hype they never made it big.

More westerns have been made about Texas than any other state; most of them are simply god-awful. Some entries in the Texas Western Hall of Infamy include Texas to Bataan, Buckaroo Sheriff of Texas, and Texans Never Cry.

FACT:

3774 dry holes were drilled in Texas in 1980.

1968 women tried out for but did not make the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders squad last season.

Four years before CBS’s Dallas hit the tube, ABC premiered its own show about a Texas dynasty: The Texas Wheelers, starring then-unknowns Gary Busey and Mark Hamill. Set in the fictitious rural town of Lamont, The Texas Wheelers told of the motherless Wheeler children—Truckie, Doobie, Boo, and T. J.—whose no-good father deserted them for months at a time. The show lasted two months. ABC’s mistake was, no doubt, in portraying its Texas family as poor but honest instead of rich and rotten to the core.

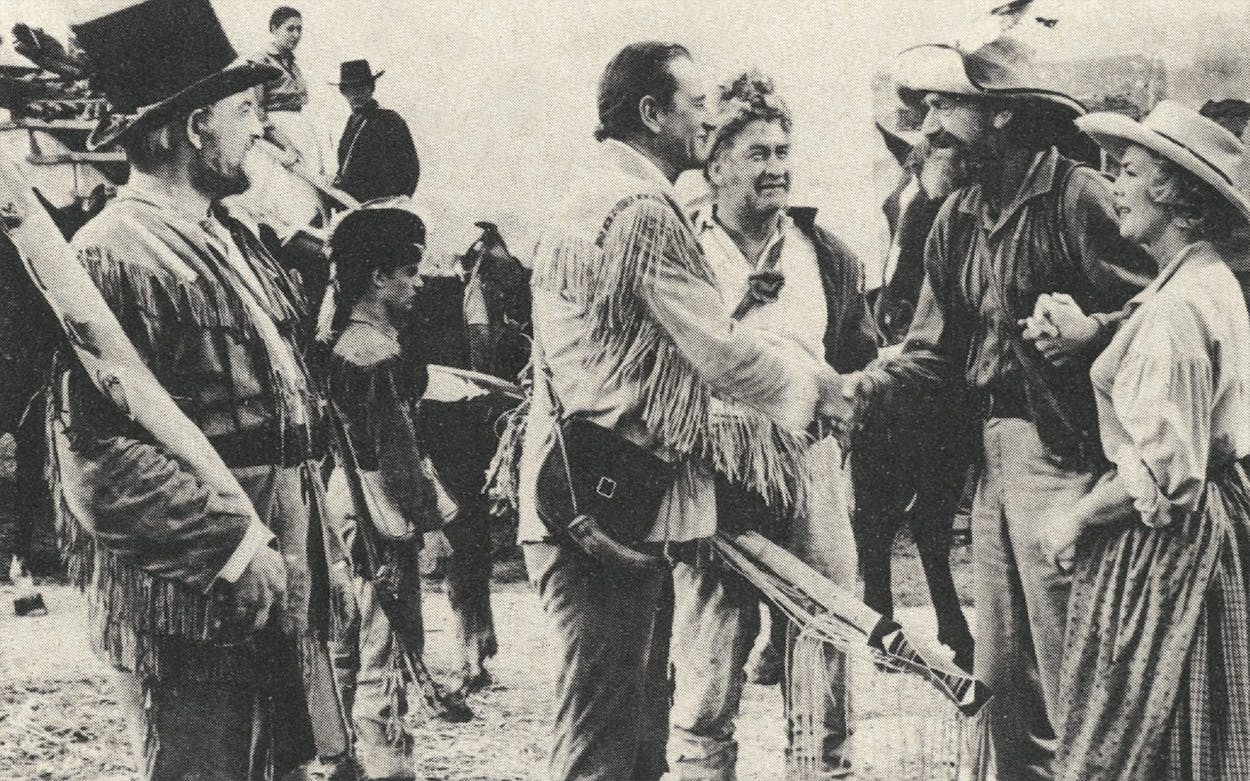

Wilson (with whip); Gates in Hell’s Half acre; Steele (head on bookcase) in Paul From Texas; Boles with friend in Stand Up and Cheer.

Stills courtesy of Hoblitzelle Theater arts Library-HRC and academy of Motion Pictures

Ideas Whose Time Never Came

Texas has always been a good place to try a new idea—consider Dr Pepper and the drill bit—but some ideas just don’t make it. Take, for example, the newspaper-throwing truck, or “mobile article launcher,” patented in 1972 by one Robert L. Lamar of Houston. As the truck drives up and down residential streets, a punched tape feeds orders to a computer to ensure that the right subscribers receive their papers. Lamar’s newspaper-throwing truck was never even a shadow of a threat to the great American institution of the paperboy.

A 1978 invention that actually saw the light of day—but not for long—was a concoction by entrepreneur Sam Lewis of San Angelo: jalapeño ice cream.

A third Texas idea that failed was an effort in 1965 by a consortium of 35 Hereford businessmen to market Bravo cigarettes, which were made not of tobacco but of Rio Grande Valley lettuce. The healthful tobacco substitute followed the first report by the surgeon general that cigarette smoking was hazardous to our health. Despite their lack of tar and nicotine, Bravos never took off in the marketplace.

Boosterism That Went Bust

Galveston started its very own football bowl in 1948—the Oleander Bowl, which pitted such giants as Wharton Junior College and Tyler Junior College against each other. Two years later, the city renamed the gripping event the Shrimp Bowl and managed to lure powers like McMurry College to headline the game. The idea just didn’t go over; the 10,000-seat stadium was never even half full, and in 1952 Galveston was reduced to playing servicemen’s teams against each other. In 1957 the Shrimp Bowl saw its last game: the defeat of the McClellan AFB Flyers by the Quantico Marines, 90–0.

In 1970 the City of Arlington, planning to capitalize on the tourist draw of Six Flags Over Texas, issued $7 million worth of bonds to finance Seven Seas, an amusement park featuring Nootka the Killer Whale, trained seals and dolphins, pearl divers, a three-masted schooner, and exactly one ride. Unfortunately, the city fathers forgot that there was no ocean within three hundred miles of Arlington. The cost of manufacturing salt water and maintaining it at just the right temperature to support the sea creatures—as well as a general lack of interest among Metroplexers—left Seven Seas high and dry. Despite the city’s attempts to turn it around, the amusement park was losing a million dollars a year by the time it closed in 1976.

Another amusement park bomb was Sawmill Town, USA, in the far East Texas county of Newton. Billed as “America’s Unique Family Facility,” Sawmill Town celebrated the Piney Woods’ great lumbering age with such non-unique attractions as buggy rides. It celebrated alone, however, as vacationers never made it to Newton County.

FACT:

7800 Texas companies went bankrupt last year.

During the utopian movement of the nineteenth century, French immigrants in Texas attempted to establish an ideal socialist state near, of all places, Fort Worth. The settlers called their new home the Icarian Colony and supported the abolition of slavery and equal rights for women, among other things. One year later, however, the colony broke up, decimated by crop failure and disease and torn by internal disputes.

Not content with being a major railway stop and air center, commerce-conscious Dallas has long sought to become a major port as well. Ships have made occasional leisurely jaunts up the Trinity River since the days of the Republic, but the business thus brought in was never steady or lucrative enough to suit Dallas. Businessmen have often pointed out that if the Trinity were deepened and widened to allow easier navigation, Dallas could rival Houston as a major Texas port.

Plenty of people jumped on the bandwagon for the Port of Dallas, including Lyndon B. Johnson, who in 1965 lent his presidential weight to getting the project authorized for construction by the Army Corps of Engineers. The estimated cost was $900 million. Big improvements on the river began in the late sixties: bridges were built, dams constructed, locks designed. Shortly thereafter taxpayers in Dallas and its surrounding counties learned that some $150 million for the project was going to have to come out of their own pockets, and the resulting bond vote sent Dallas’s seaport dreams down the drain.

Cereal king C. W. Post, creator of Grape Nuts and Post Toasties, decided in 1906 that he would build the model Texas city. Post had come to Texas from Illinois for the warmer weather but, as a health food fanatic and a Christian Scientist, was dismayed at the rotten moral fiber of Texans. He selected Garza County, at the edge of the High Plains, as the site for his ideal city and began building the town of Post. He then marked off 150 quarter-section farms, each complete with farmhouse, barn, and low-interest loan.

Alas, Post had difficulty luring settlers, partly because of his stringent rules (no liquor, for one) and partly because the lack of rain in the area made the success of pre-irrigation farming unlikely. Post tackled the aridity problem with a vengeance by exploding dynamite on the theory that the agitation of the air would produce rain. Sure enough, it did—but the cost per explosion was excessive and the noise further discouraged prospective citizens. When the railroad ultimately bypassed Post in favor of Lubbock, the lack of commerce was just one more factor that kept Post from becoming the model city its founder had envisioned.

Houston’s Metropolitan Transit Authority, which costs the city’s voters $100 million in taxes every year, is designing a mass transit system that will, according to the MTA’s own estimates, do nothing to alleviate traffic congestion by the time it’s put in.

Archeologists who thought they had found artifacts placing early man in the Dallas area some 40,000 years ago—30,000 years earlier than in any other site in the Western Hemisphere—were proved wrong by carbon dating tests. The Dallas area, it turned out, is no more advanced than anyplace else in America.

FACT:

33 Texas cities are on the federal government’s list of urban areas in which you are most likely to die during a nuclear attack.

None of Their Businesses

In 1953 Galveston’s city commissioners decided Pelican Island was Texas’ ideal manufacturing site and okayed a $17 million contract to develop the island. Eager chamber of commerce types called Pelican Island “the best real estate buy in the U.S.” and claimed that all sorts of businesses were interested in relocating there, from grain elevators to a Texas branch of Disneyland. A six-lane bridge from the mainland to the island opened in 1958, but the scads of industrial plants failed to materialize—perhaps because of the damage caused by Hurricane Audrey the previous summer, perhaps because of a particularly voracious species of termite found on the island.

Clayton McKenzie’s first mistake, no doubt, was starting up a rent-a-cow company for dairymen in a ranching state. His Quality Holstein Leasing Company filed for bankruptcy just a few months after the Palestine businessman had predicted that in 1981 the firm would “do” $30 million—a figure that turned out to be closer to the rent-a-cow agency’s liabilities.

When foremost Fort Worther Amon Carter, Sr., announced his intention to build the budding Metroplex a bigger and better airport, the City of Dallas refused to go in on the deal unless Carter built the terminal facing Dallas.

Carter would have none of that, and Cowtown went ahead and built its own airport at a cost of $18 million. Carter was able to persuade American airlines to land in Fort Worth—he was a major shareholder—but Love Field still got the majority of air traffic. Amon Carter Field (later known as Greater Southwest International Airport) never took off; when DFW airport opened in 1974, Carter’s field closed. A development corporation bought it in 1979, and today its north-south runway is a boulevard.

Horizon City, a desert suburb of El Paso, was a 1957 development that grew out of El Paso’s population boom. But the boom did not extend the city limits twenty miles into the desert, as the developers had optimistically hoped. The 87,000 acres they had targeted for development just sat there—to the dismay of thousands of investors, most of whom had bought the property sight unseen, never intending to live there but only to rake in the returns.

Responding to complaints, the Federal Trade Commission charged the developers with using misleading sales tactics. The developers agreed to spend $45 million on improvements to the property (such as a thousand miles of graded roads) and to earmark another $14.5 million to be returned to eligible buyers. To other unhappy landowners Horizon City offered a deal: an even trade of a lot way out in the boonies for one closer to town—but still, of course, in the desert. Today, 24 years after the project began, less than 2 per cent of Horizon City’s original acreage has been developed.

FACT:

1682: Texans violated one or more of the state’s parole rules in the 1980–81 fiscal year, had their paroles revoked, and were sent back to prison.

379,000 Texans did not meet the April 15 income tax deadline this year.

1634 dealers in cocaine, marijuana, heroin, or other dangerous drugs in Texas last year were busted by the federal Drug Enforcement Administration.

FACT:

1682 Texans violated one or more of the state’s parole rules in the 1980–81 fiscal year, had their paroles revoked, and were sent back to prison.

379,000 Texans did not meet the April 15 income tax deadline this year.

1634 dealers in cocaine, marijuana, heroin, or other dangerous drugs in Texas last year were busted by the federal Drug Enforcement Administration.

Texas’ most famous bordello, the highly successful Chicken Ranch, failed miserably when entrepreneurs hoping to cash in on its notoriety moved it from La Grange to Dallas and turned it into a restaurant.

Between 1973 and 1977, some five hundred Texans invested in Wolfe Pecanlands, a pecan orchard company with 10,000 acres in Erath and Comanche counties. The orchards, densely planted to ensure the highest possible yield, were scheduled to produce their first crop five years after the project was started—then six years, then seven. Investors, anticipating big bucks from nut-hungry Americans, poured close to $5 million into the company before Congress passed a law that forbade the deduction of growing expenses, which effectively removed all tax incentive to invest in the orchards. Next, an attempt to sell five-year bonds that could be converted into land in the pecan orchards failed when interest rates zoomed. In 1981, Wolfe Pecanlands was more than $7 million in debt. Aw, nuts.

Seadock, a proposed superport to be constructed 26 miles off the coast near Freeport, would have been equipped to handle supertankers of 100,000 tons and up—if it had ever gotten under way. Its backers, a consortium of oil companies including Exxon, Gulf, and Mobil, were willing to sink more than $700 million into the superport—which would have given Texas its only dock big enough for the giant crude oil carriers—but, inevitably, Seadock needed a go-ahead from the federal government. That was the rub. The feds didn’t like Big Oil’s proposals, Big Oil didn’t like the feds’ restrictions, and Seadock didn’t get built.

In 1973, Friendswood Development Company, a subsidiary of Exxon, began work on Richmond Landing, a planned community in Fort Bend County, only to drop the project when the developers discovered that the land was ten feet under the hundred-year floodplain.

Millionaire oilman Jack Grimm of abilene has financed expeditions to unearth Noah’s ark (1970), to photograph the Loch Ness monster (1976) and Big Foot (1977), and, this year, to locate the wreckage of the Titanic. So far he hasn’t found what he’s looking for.

Close, But No Cigar

Baseball phenomenon David Clyde, who in 1973 began pitching for the Texas Rangers right out of Houston’s Westchester High School, won his first major league game ever in front of a cheering sellout crowd. That night was the high point of his career; between 1974 and 1978 he didn’t win a single major league game. Traded back and forth between Texas and Cleveland and shuttled in and out of the minors, Clyde never lived up to his storybook beginning. Today he plays for the Tucson Toros.

In 1967, a little-known Dallas lawyer named Eugene Locke announced that, with outgoing governor John Connally’s blessing, he was running for the gubernatorial seat. Locke spent an undisclosed but admittedly large sum on his race, most of it on TV and radio ads featuring a jingle that began, “Eugene Locke should be governor of Texas.” The state’s voters could hum the tune, but they didn’t like the idea: Locke came in fifth. Actually, we all lost this election—the winner was Preston Smith.

Nipped in the Bud

Outlaw Sam Bass, 23, had held up exactly five trains before he decided to switch to bank robbery and was gunned down in Round Rock by Texas Rangers during his first heist.

Candy Barr was only 22 when her 1957 marijuana arrest put an end to her SRO strip act at Dallas’s Colony Club.

Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow, ages 23 and 25, respectively, when lawmen cut short their crime spree, could have done so much more.

FACT:

424,142 Texans had wrecks in 1980 because they failed to obey traffic rules.

There but for the Grace of God

When the Astrodome opened in 1965 its fields were covered with grass—a feeble grass, true, but nevertheless real grass, a type specially developed by Aggie scientists to grow indoors. It got sunlight through the clear plastic panels of the Astrodome roof. Not until baseball season started did the Astrodome management become aware of a problem: the glare through the roof blinded players whenever they looked up to snag a ball. The way to get rid of the glare was to paint over the roof, but then the grass would die. What to do? The solution: AstroTurf. With artificial grass there would be no blinding glare, no dying grass, no barrier to the astrodome’s fame. Whew—that was close.

- More About:

- Texas History

- TM Classics

- Longreads