This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Ten years ago, thirty-year-old British rocker Ronnie Lane was an appropriate hero for rags-to-riches stories. He had come from gritty obscurity to become a world-class star. Today at forty, Ronnie Lane, who recorded the Rough Mix LP with Pete Townshend, can’t work at all. He spends his time sitting and talking, like a widow whose estate has withered. The victim of an incurable disease, he came to Texas looking for a cure. He found Mae Nacol, a fellow sufferer and a Houston attorney. A year later, $1 million that he had helped raise for medical research and patient services was spent, and Lane and Nacol were entangled in lawsuits.

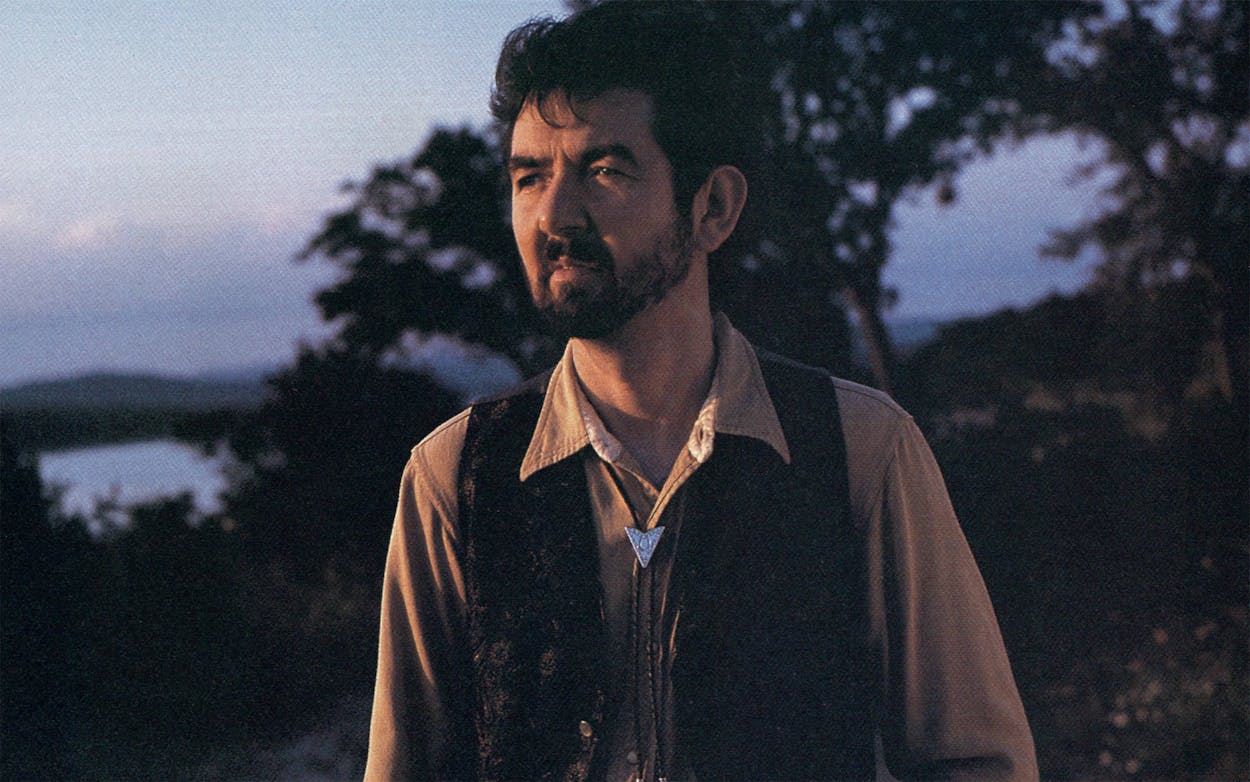

Ronald Frederick Lane is black-haired, brown-eyed, and diminutive, a pale 110-pounder even at the peak of health. He was raised in an East London neighborhood that was a ruin because bomb damage from World War II had never been repaired. His father, Stanley Lane, often took Ronnie on weekend rural outings to show him that a more elevated lifestyle was possible. “But I always figured that the country wasn’t for me,” Ronnie recalls. The hills and countryside were for the rustic and the rich, and the Lane family was neither: Stanley was a truck driver, and Elsie Lane, Ronnie’s mother, was a factory operative—that is, until she became what her son dreads becoming, an invalid and a cripple.

Ronnie escaped from the dim plane of his childhood by following his father’s advice. “If you’ll learn to play an instrument,” Stanley Lane told him, “you will always have a friend.” Around 1960 Stanley bought his son a guitar. Ronnie learned to play without lessons, and in time the guitar brought more than companionship. In 1963 Ronnie went into a music shop to look over a bass guitar. Nine months later, he and the store’s salesman, Steve Marriott, were playing part-time gigs in a group they named the Small Faces. Their first single reached the British pop charts in 1965; “Itchy-coo Park,” their best-known American release, crossed the Atlantic two years later. Rod Stewart replaced Marriott in a reconstituted group, the Faces, which toured Europe and the United States in 1970. Stanley Lane’s obedient son had brought his father’s fantasies to life.

With his first surge of wealth, from the Small Faces, Ronnie Lane bought his parents a new house, outside gray London in the green suburb of Romford, and in 1973, he bought a rural refuge for himself. With his wife and two sons he settled into the life of a sheepherder on a hundred-acre farm high in the hills between England and Wales. Lane’s fence line marked the boundary between the two. His lair was almost inaccessible, and he liked it that way. Distance, drizzle, and fog kept casual admirers and hangers-on away from his door, but people who cared greatly still arrived. Eric Clapton came to visit and, just as important, Stanley Lane came too. Ronnie’s father spent ten days on the farm in 1974, puttering just for his own amusement.

Ronnie Lane had escaped the rat race of the music industry by ascending to the hills, but he hadn’t left his creative work behind. While on tour in America with the Faces, he had become an admirer of curvaceous Airstream trailers. He ordered one, and when it arrived in England, he equipped it as a mobile sound studio and parked it outside his farmhouse. On mornings when he felt like being a musician, he stepped into his Airstream, oblivious to his sheep. In 1976 guitarist-songwriter-singer Ronnie Lane had a father, a family, a farm, and a small fortune in the bank.

Cancer took his gray-haired father before the year was out. “I thought I took it pretty well at the time,” Lane says. But when he says that, and when he says many other things today, there’s a shadowy, self-mocking sarcasm in his voice. Nine months after his father’s death, Ronnie Lane was stricken by an ominous, then incomprehensible sign that he now interprets as a silent wail of mourning. While sitting in his Airstream with a guitar, Lane discovered that his left hand would not work anymore. Its fingers would not grasp. “I could not get them around a riff,” he remembers. Not knowing what to make of his sudden, mysterious, and painless disability, Ronnie Lane did nothing about it. Weeks later, Gypsy friends who lived nearby took him to a chiropractor who kneaded Lane’s back, neck, and limbs. The afflicted hand came back to life.

A second sign visited him during the dead of winter in 1977–78. Lane’s left leg began to fail him. It seemed so weak and unresponsive that he couldn’t walk steadily. He had no idea what was gnawing at him. Neither did his chiropractor, whose treatments didn’t work a cure. The malady dogged Lane for months, then went away overnight, as mysteriously as it had come. He put away the cane he had used during the siege and returned to living as usual, without giving the incident much thought.

At a livestock show held during the spring of 1978, Lane was visited by a third sign. He saw two prize cows on exhibit, when there was only one. He was seeing double. That defect, unlike his hand and leg difficulties, did not go away. Back on the farm, Lane had to give up his daily count, because he always saw more sheep than were in his pastures. After a few days, he decided that he’d had enough of inscrutable signs. Ronnie Lane came down from the hills to see a specialist. Two weeks later in a hospital in Birmingham, a neurologist approached his bed to speak the words that would become more important to Lane than any lyric he had ever written. “I’m afraid we’ve got some bad news,” the doctor said. “You’ve got multiple sclerosis.”

MS is a crippling but rarely fatal disease whose origin and effects are in many ways matters of guesswork and controversy. For example, some researchers and many victims associate the onset of MS with emotional trauma, as Ronnie Lane did; others deny that multiple sclerosis has anything to do with the psyche. The disease is not subject to easy confirmation. Only at death can a sure diagnosis be made.

Autopsies show that people who suffer from more than one of a cluster of disabilities—including dizziness, partial or complete paralysis, fatigue, incontinence, slurred speech, impotence, blindness, or double vision—often have a common condition. Patches of myelin, a fatty insulating material that sheathes the nerve fibers in the brain and the spinal cord, have been destroyed and replaced by sclerota, or scar tissue, a faulty insulator. The result is that electrical impulses from the brain to the sense organs or limbs are feebly transmitted or quit arriving altogether. MS sufferers display different symptoms, and different symptoms arise at different stages of the disease, depending upon just how far demyelination and scarring have advanced. Because no single laboratory or clinical test yet devised is capable of yielding a foolproof diagnosis, multiple sclerosis victims usually spend years wondering if they really have the disease or if—hope against hope—they may have been spared.

MS was discovered in 1835, but its cause is still unknown. It is a rare disease, afflicting perhaps two million people, including some 250,000 in the United States. It is not communicable, and although it is not directly inherited like Huntington’s chorea—the nervous system disorder that killed Woody Guthrie—a predisposition toward multiple sclerosis may be genetically transmitted. MS occurs mainly among the inhabitants of cold climates and mainly among whites. There is evidence that the disorder picks its victims in childhood, though as in Ronnie Lane’s case, it usually does not name them until they have passed the age of twenty. Researchers have long suspected that a slow-acting virus instigates the disease—everything from soil minerals to dogs has been suspected of harboring the elusive agent—which apparently does its damage by befuddling the body’s immune system.

Ronnie Lane accepted his diagnosis with the same apparent stoicism that he had summoned to take the news of his father’s death. “So this is it,” he thought to himself. But the specter of MS was doubly threatening for him. He already knew what the disease could mean. His mother had been a victim for years, and the disease had done nothing for their relationship, which he describes as “sparse.” When Stanley Lane had bought his son that first guitar, Elsie Lane snapped at her husband, “What did you do that for? You know he’ll never do anything with it.” In 1974, when Stanley had come to the farm, Elsie opted for a seaside holiday sponsored by the Multiple Sclerosis Society of Great Britain and Ireland. His mother, Ronnie believed, had plagued the Lane homestead with ill humor and pessimism. He regarded her crankiness as a symptom of her disease. He didn’t want to end up like Mum, and he couldn’t bring himself to forgive her.

Ronnie Lane came to Texas in June 1984, in bad shape. Half of him—the left half—wasn’t much good anymore. Lane’s left eye gave him a view “as black as a coal hole,” and the eyeball wandered, besides. His left hand couldn’t grip a guitar neck, and his left leg wouldn’t support the weight of his skinny torso. He was divorced and deeply depressed. On a visit to his bedridden mother, she had told him, “Oh, you’ll never walk again!” His resolve, and only his resolve, told him that his mother was wrong. Ronnie Lane was determined to walk again, even if he had to discover a cure for MS to succeed.

Lane’s knowledge of MS wasn’t much more sophisticated than his mother’s. Having dropped out of school at sixteen, he could barely digest medical bulletins on the subject. But he did have one asset to contribute to research, albeit research of the most questionable kind: he could use his body as a test tube. So Ronnie Lane did that. For example, in 1982, though the British MS Society advised against it, Lane had taken injections of viper and cobra venom for four months on the theory that it might jolt his bloodstream into battling his disorder. The same year, he began hyperbaric oxygen, or HBO, treatments. HBO patients enter high-pressure chambers and breathe an atmosphere of nearly pure oxygen, usually for one or two hours. The treatment is effective in relieving deep-sea divers of the bends, but its usefulness in treating multiple sclerosis has not been established; the National Multiple Sclerosis Society in America says HBO is of negligible value. But almost every disease has periods of advance, when symptoms appear or reappear and the patient feels worse, and periods of remission, when symptoms disappear and he feels better. This pattern in the advance of disease, two steps forward, then one step back, often confuses victims about their state of health. If during a stage of advance or relapse the patient undergoes a treatment—almost any treatment, especially one whose effects are harmless—and continues with it until reaching a period of remission, he is likely to feel that the treatment, and not the tricky dance step of disease, is responsible for his improvement. Lane tried HBO treatments for his MS, and his speech cleared, after having been slurred for some six months. He was convinced that he had arrested his disease and might one day recover entirely.

The guitarist had learned of the experimental cure through a British organization called Action for Research into Multiple Sclerosis. ARMS differed from the mainstream Multiple Sclerosis Society of Great Britain and Northern Ireland in two respects. First, its membership was limited; only MS victims or their loved ones could join, hold offices in the organization, or serve on its staff. Second, ARMS and its members were more venturesome than the mainstream MS Society. The MS Society, for example, had urged its followers to turn a deaf ear to HBO claims until the treatment could be fully evaluated. Like most ARMS members, Ronnie Lane had concluded that the MS Society was too mired in self-serving bureaucracy to be counted on to deliver a cure. Though he could speak clearly and the fatigue that characterizes MS seemed to be gone, he still could not see from his left eye nor grasp with his left hand, and by 1984, when he decided to return to America, he could move about only in a wheelchair. He had two objectives in coming here. He wanted to be able to take as many HBO treatments as he thought he needed, and wheedling HBO time out of England’s socialized medical system had become a hassle. He also wanted to look into the possibility of founding an ARMS organization in America.

During the summer of 1983, Briton Glyn Johns, the producer of the Small Faces, lured England’s leading rock stars to a London benefit concert for ARMS. The show was so successful that American promoter Bill Graham brought it to four American cities that fall—New York, Dallas, Los Angeles, and San Francisco. “The British Are Coming,” as the tour was called, put the likes of Jeff Beck, Jimmy Page, Charlie Watts, Bill Wyman, Eric Clapton, and Joe Cocker on the same stage. Lane closed performances by singing “Goodnight, Irene.” The production was an artistic milestone, and it raised a little more than $1 million for ARMS, a sum that Johns and other backers believed should be used to benefit America’s MS sufferers. But when Ronnie Lane came to America in June, the concert lode was sitting in a British bank, like an MS victim, waiting out an uncertain fate.

On the advice of a Scottish physician, Lane flew to Texas for treatments at the Houston HBO Medical Center, a small, four-chamber facility founded by Mae Nacol, 42, a raucous-voiced, olive-skinned, chubby woman of Lebanese extraction. Accompanied by a thinner, more sedate woman, Barbara Nacol, 38, she met Lane at the airport. Mae introduced Barbara as her sister and invited him to stay at their home during his visit. The offer gave him an opportunity to get an insider’s look at Texas, a state that in his mind had been “just another spot on the gig circuit.”

Mae Nacol owned a 74-acre ranchette just outside the city, but she and Barbara lived in a spacious two-story house at 6012 Memorial Drive, in a prosperous neighborhood. Mae hadn’t been a fan of Lane’s, but during the weeks he was at her home, she won his respect. Lane was especially heartened to learn that though she had no obvious disability, Mae Nacol had MS too. Her apparent good health and vigor, she said, were owed to HBO treatments. In 1978, according to her account, she had been nearly blind, couldn’t feed herself, and had begun to lose her hearing. Her doctor advised her to give up her legal practice. Instead, she had flown to Florida, where HBO treatments were available. After the thirteenth session she had regained bladder control and had become a believer in the cure. By her twentieth entry into the HBO chamber, she had begun to walk. She returned to Houston to build her law practice and resume a normal life. To reduce the cost and delay of treatments in Florida, she helped establish the Houston HBO clinic, under the supervision of Montrose-area physician F. O. McGehee. Barbara Nacol had become its manager.

Lane discovered that Mae too was skeptical of the National MS Society’s reliance on viral and immunological research. They both believed that more-practical means were needed to find a cure. And they agreed that the one way to break the lock that the medical establishment had on research was to establish their own organization. Ronnie Lane came to see Mae Nacol as the perfect leader for an ARMS organization in America. “She was rich, she was an attorney, and most important of all,” he says, “she had MS.” Lane suggested that she found an American branch of ARMS, but she was reluctant. “I had a very comfortable life,” Nacol told a newspaper reporter. “I didn’t need the headache or heartache of ARMS or the stress in my life. With this disease, you can’t handle distress.”

But Lane persisted, and after several days, Mae Nacol relented. The HBO treatments Lane was receiving in Houston did not put him back on his feet, but the whole experience, he recalls, “brightened me up a bit.” He went home to England, determined to see that the unspent $1 million was sent across the Atlantic, into the care of Mae Nacol.

Mae Nacol, born Willie Mae Nacol, had graduated from Houston’s prestigious Bellaire High School and from Rice University. She came from a family that was well known to police patrolmen and daily news addicts. In the ten years preceding Lane’s visit to Houston, Mae’s mother had been pistol-whipped to death. Her father, a prosperous jeweler, had been repeatedly robbed at gunpoint—once for half a million dollars in loot—and he had been kidnapped. Her elder brother had his medical license revoked for administering a hormone treatment of doubtful value (his license was subsequently reinstated), and in 1978 Mae had added to the family’s reputation by going to bankruptcy court.

Mae Nacol’s Chapter XII reorganization was not a disastrous affair. She continued to operate her law firm and even managed to salvage a few luxuries, among them items of personal jewelry valued at $20,000. But Nacol did have grave financial problems—she owed more than $1 million—most of them brought on by the failure of Houston Town & Country, a society-oriented magazine. Before the publication closed its doors following a fire in the spring of 1977, Mae’s partner in the magazine was Linda Hudson, a woman whose usual occupation was as a psychologist for the Houston school district. Though the financial records she filed with her pleadings weren’t complete—Nacol alleged that some of them had been stolen by a former law firm associate—some of her unsecured creditors who had loaned money to her without requiring collateral took significant losses. One of them was Linda Hudson, who had loaned some $42,000 to Nacol. During the six months following the end of her relationship with Hudson, however, Nacol found a new source of unsecured loans—her legal secretary, Barbara Leigh Hunt, the same woman who was later introduced to Ronnie Lane as her sister Barbara Nacol. Barbara loaned Mae about $30,000.

By 1978 Barbara Leigh Hunt was not only Mae’s secretary. She was also Mae’s housemate. She lived with Mae, and according to bankruptcy court records, Barbara, like Linda Hudson before her, had a key to Mae’s safe-deposit box. Twice in the ensuing years Mae, an attorney, would state under oath that she and Barbara were sisters. Barbara was not Mae’s sister either by birth or by adoption. Nor had Barbara been born with the Nacol surname. In October 1977, by means of a legal instrument drafted by Mae’s office, Barbara Leigh Hunt changed her name to Barbara Leigh Hunt Nacol. The change substantiated the impression that the two women were sisters, indeed.

In the early fall of 1984, some three months after Ronnie Lane’s return to England, Mae and Barbara flew to London, where they spent nearly three weeks. After meeting with ARMS leaders, the two women returned to Houston with plans to shut down Mae’s law practice and to give birth to a new organization, ARMS of America. In December 1984 British rockers Kenny Jones, Jeff Beck, Glyn Johns, and Ronnie Lane came to Houston to present Mae Nacol with a $1 million check from UK ARMS, for the founding of its transatlantic counterpart. ARMS of America, its bylaws said, was to be run by a general membership of MS victims and their loved ones and was to be directed by a board of six, including Ronnie Lane and a British authority on HBO, Dr. Philip James. The purpose of the new organization, its literature proclaimed, was “to further research into the cause, treatments, and cure for multiple sclerosis.”

The board of the new organization met in Houston on December 11. It took several steps that most of its members would regret in future months. It abolished the general membership’s voting rights. It elected a slate of officers and authorized them to serve as the organization’s executive committee, charged with managing the day-to-day affairs of ARMS of America. Barbara Nacol became ARMS president; Carol Kent, an attorney in Mae Nacol’s employ for some fifteen years, became its vice president. Mae Nacol was named secretary, and Beverly Ashley, the wife of one of Mae’s first law clients, became the organization’s treasurer. All four were beneficiaries of the ARMS payroll. Only Mae Nacol would have been eligible for membership in ARMS as an MS victim. Ronnie Lane was not a member of the executive committee.

Lane decided to stay in Houston to help see ARMS through its childhood. He came into its office almost every day to answer calls on the organization’s 800 number for MS victims. He met the press, appeared at rock shows in his wheelchair, and lobbied with musicians to stage benefit concerts. He also tried to rebuild his health. He did weight-lifting exercises. He went swimming, and two or three times a week he checked into the HBO Center for an hour’s free treatment in a cylindrical chamber resembling the iron lung of the polio era. He made dozens of friends and, as always, kept on the alert for news of possible cures.

One of his new friends was Don Shoffner, a thoughtful, fleshy, middle-aged veteran of the awareness movement. Shoffner is a disciple of Robert Rasmusson of California, the originator of something called the Regenesis Process of Healing. A Rasmusson handbook says that “REGENESIS is the practice of mobilizing and directing the flow of cellular energy to stimulate, accelerate, and facilitate the natural healing processes.” The healer, or “facilitator,” the manual says, “acts as a catalyst, providing the spark, much like a battery and a jumper cable between cars.” Shoffner persuaded Lane to take the role of a car with a dead battery as he played cable. In a series of treatments, he laid his hands on Lane and, while breathing deeply, meditated on the coming spark of new life. But nothing happened. Since Shoffner charged nothing for the boost and it did no harm, he and Lane remained friends.

Ronnie Lane saw Mae Nacol frequently during 1985, usually at the ARMS office. They discussed fundraising plans, the efforts to publicize ARMS, and other affairs connected to their common cause. They sometimes discussed incidental expenses, but they didn’t review the ARMS expenditures because, Lane says, “that was mainly, you know, beyond my understanding.” That failure led directly to Lane’s legal troubles. Lane trusted Nacol; that was the basis of their collaboration. He also had his health to worry about, and he didn’t want to pay attention to petty squabbles. He and his associates stayed at the edge of the daily bureaucratic life of ARMS, and they stayed out of the seemingly ordinary tiffs that developed among office workers there. But by the summer of 1985, though they didn’t tell him, some of Lane’s associates began to experience inexplicable difficulties with a half-dozen staffers at the office. Mark Bowman, the official photographer for ARMS, quit going there because “the vibes were just too bad.” None of Lane’s confidants warned him about the trouble in the office, however, because they didn’t suspect that it could be fateful for ARMS. They didn’t fathom what was afoot: the unraveling of the relationship between Mae and Barbara Nacol.

“Basically, there was a real disagreement between Barbara and I on a personal level,” Mae Nacol testified in a deposition, but she refused to be more specific about their differences. In October, when the six members of the ARMS board met—for the first time in 1985—Barbara Nacol opened the session’s business by offering to resign as president. Her resignation was accepted. Explaining that “Barbara’s concerns are not the best interests of ARMS but revenge upon me,” Mae Nacol then proposed that Barbara be removed from the board of directors too. Barbara protested, but the motion passed; Barbara was purged. Philip James, who had come from Scotland to attend the meeting, proposed in exasperation that Mae be purged from the board as well. His motion was defeated. Mae Nacol ordered the locks changed on the doors, apparently to bar Barbara’s reentry, and then, at the opening of the board’s second meeting that year, in November, she submitted her own resignation.

Ronnie Lane says he didn’t really understand what was going on at ARMS during the feud; until late October, when Barbara reverted to the surname Hunt, he believed that she and Mae were really sisters. He cast his support with Mae, almost on the basis of instinct; Mae, in all her dealings with him, had been perfectly gracious. For example, earlier in the year, when he and a longtime girlfriend had reached a parting of the ways, Mae had arranged for him to have a full-time, live-in attendant to drive him to the ARMS office and the HBO clinic, to prepare his meals, and to help him care for his apartment. When he had run out of money early in the summer of 1985, she had seen to it that his bills were paid. Lane knew that ARMS funds had been expended to cover some of his expenses, but he says he didn’t realize that this was wrong. In any case, he believed that Mae had paid for most of them out of her own purse.

He soon began to doubt both Mae and Barbara Nacol, but not for financial reasons. In early October, about the time that Barbara Nacol was purged, Jo Rae DiMenno, a slender Houston brunette, had paid a confidential visit to Lane’s apartment. Lane knew DiMenno from her work as a publicist for nightclubs and from contacts she had made with ARMS. For several months DiMenno had been in touch with two Houston MS victims who were back on their feet again after making visits to an Iowa doctor. Both MS sufferers had tried to reach Lane with news of their sudden recoveries, but the messages they had left for him at the ARMS office had never gotten through. DiMenno had come to Lane’s apartment to tell him about the Iowa recoveries and to warn him that she suspected that the Nacols were more wedded to promoting HBO than to investigating every possible cure. She returned a few days later to give Lane a copy of MS: Something Can Be Done and You Can Do It, the book that explained the theories of Robert Soll, the doctor who developed the Iowa treatment. Lane hadn’t ceased casting about for a cure. He was already scheduled to enter a Houston hospital for tendon surgery on his left foot, another long-shot procedure, and when he went into the hospital, he took Soll’s book with him. It explained a theory new to Lane, that allergic reactions can exacerbate multiple sclerosis and possibly even play a causal role. Lane’s tendon surgery was unsuccessful, but upon release from the hospital, though he had read only half of the doctor’s book, he flew to Iowa for a turn at Soll’s clinic.

Accompanying Lane on the trip was Jo Rae DiMenno, in her newly acquired status as an unpaid replacement for his ARMS attendant. Lane and DiMenno checked into a public hospital and, at Soll’s instruction, observed a distilled water diet for four days. Their hunger was especially hard to bear, Lane recalls, because one of the fasting days was Thanksgiving. During their fast, as prescribed by Dr. Soll, Lane and DiMenno swallowed daily doses of niacin, a vitamin that causes flushing of the face and neck. By the time they had finished their fast, niacin—used liked dental disclosing tablets in Soil’s treatment—no longer caused them to flush. Under their own and medical observation, they began rebuilding their usual diets, food by food, taking one hundred milligrams of niacin before each meal. Lane’s pulse quickened, and he flushed badly after eating several foods, eggs and avocados among them. On Soll’s advice, he eliminated those and other items from his diet. On the morning of December 7, about two weeks after he had begun the Iowa treatments, he surprised DiMenno by standing to shave himself at the sink in their hospital room. Though his steps were still shaky and he sometimes needed support, he amazed his friends back in Houston at Christmas by walking up the stairs to his second-floor apartment. The progress he had made was astounding.

His regained strength and his enthusiasm for diet therapy gave Ronnie Lane a new perspective on HBO, the Nacols, and ARMS. He thought that the organization’s marriage to HBO had not been in the best interests of MS victims, and he wondered why the Nacols had not shown a greater interest in allergy treatments for the disease. As a member of the ARMS board, he demanded access to its records just in case the rumors of mismanagement were true. His demands were deflected. The records had been stolen during the feud, he was told. He asked questions of the remaining officers and employees. Most of them professed not to know what had gone on before the feud and denied knowing why it had begun. ARMS had become a zombie, almost like Ronnie Lane had been; it moved slowly and was without self-knowledge. Frustrated, Lane turned to Don Shoffner for help. This time the guru had a practical answer. His wife, Elizabeth, was a legal secretary. She agreed to tell her boss about Lane’s problems at ARMS.

Elizabeth Shoffner’s employer was Larry Hysinger, 36, who had an impressive memory for music and was a fan of Lane’s LP Ogden’s Nut Gone Flake. He volunteered to represent Lane without charge. Hysinger demanded an airing of the ARMS archives. He won permission from the new ARMS director, Ira Morel, for the Shoffners to make copies and lists from its bank statements. The Shoffners compiled a history of ARMS financial transactions that, Hysinger believed, showed evidence that both Barbara and Mae Nacol had abused the organization’s trust. Arms responded to Hysinger’s charges by voting to expel Lane from its board, but in early March Hysinger took the financial lists to the Texas attorney general’s office and appealed for an investigation. On March 31 his request was granted; a state district judge appointed a temporary receiver for ARMS. The receiver’s report, released three weeks later, upheld most of Hysinger’s charges and recommended that ARMS be dissolved. The receiver, Ron Sommers, a Houston bankruptcy specialist, found that “the affairs of ARMS had been mismanaged,” that there had been “a pattern of self-dealing between the board of directors, executive committee, and officers,” and that “various expenditures authorized by the executive committee and officers were inappropriate.” He also found that ARMS was nearly broke. Only one of the Houston benefits it had staged had shown a profit. During less than eighteen months of existence, U.S. ARMS had an income of $1.2 million, including the founding $1 million check. Only $90,000 was left.

Where did the money go? The receiver’s report says that ARMS spent more than $1 million in administrative expenses, including $450,000 in salaries and legal fees. The members of the ARMS executive committee voted Mae’s salary at the equivalent of $200,000 a year, $80,000 of it designated as her salary as ARMS secretary, $120,000 designated as a legal retainer, paid at $10,000 a month. By comparison, the president and CEO of the National Multiple Sclerosis Society, an organization with a $40 million annual budget, earns $120,000 a year.

Mae was amply compensated for expenses too. She was reimbursed $25,868 for expenses incurred by starting ARMS in the U.S., including the trip she and Barbara had made to England in the fall of 1984, and she was reimbursed an additional $19,930 for organizational expenses incurred mainly during 1985. ARMS bought Mae’s Lincoln limousine. One check drawn on the ARMS account was made payable to Nacol’s Jewelry of Houston, for $650. No receipts or other documents supporting the check were found, but Mae Nacol says that the $650 was spent for two watches bought as gifts for Ronnie Lane’s sons.

Almost everyone had gotten a piece of the pie. Barbara Nacol, titular president, was paid an annual salary of $72,000. ARMS had paid attorney Carol Kent a salary of $40,000 to handle Mae’s private legal work and to serve as vice president of the organization. Beverly Ashley, the organization’s part-time bookkeeper and treasurer, received some $18,000, and her husband, the ARMS office handyman, was paid about $32,000 for services as varied as “research” and supplying potted plants to adorn the premises. Three public relations firms hired by ARMS for different services were paid a total of $123,000 in retainers and fees. A newsletter published early in the organization’s history promised that ARMS of America would spend some $450,000 to fund research grants during its first year of operation. Instead, it spent $67,000, just 5.6 per cent of its budget. Additional funds went for an 800 number, information sheets for MS victims, and starting a videotape library and a computerized library of research information.

In court documents Mae Nacol vigorously defends her actions. She was promised, she says, that she would be reimbursed for expenses incurred in setting up ARMS. It was also agreed, she says, that she would receive $200,000 in compensation during her first year. (The receiver, however, contends that Nacol promised ARMS of England that she would not charge ARMS any salary or legal fees; Nacol says that she only promised to donate her time spent in setting up ARMS in America and securing its tax-free status.) She also takes issue with the receiver’s characterization of the financial condition of ARMS. Personal property and other assets in addition to cash make the net worth of ARMS $300,000 to $400,000, she contends. She adds that “additional fundraisers were anticipated in the near future.”

The receiver’s report justified Ronnie Lane’s belated skepticism about the financial life of ARMS. But it only added trouble to his life. He too had been a beneficiary of money from ARMS, money he cannot now repay. Because he was also a director of ARMS, a position of trust with regard to its assets, the court-appointed receiver on May 14 filed suit against him, along with Mae and Barbara Nacol and two other defendants. The result is that the receiver accuses them of the same acts—breach of fiduciary duty, constructive fraud, actual fraud, and negligence—although Lane and Nacol held vastly different positions in the day-to-day operation of ARMS.

In June, Mae Nacol filed suit in federal court against Lane, Hysinger, the receiver, the attorney general, and others. She seeks to nullify the receivership and recover $10 million in alleged damages for libel and slander. One of the issues in the case is whether the attorney general has the right to intervene in the affairs of ARMS at all, since ARMS is a nonprofit corporation, not a charitable trust. The suit also accuses the attorney general’s office of intimidating ARMS workers in “Gestapo fashion” by showing up at the ARMS offices with an armed guard and demanding access to records. Nacol also protests that a copy of the deposition she gave the receiver has never been returned to her for corrections and signature.

At the expense of his friend Pete Townshend, Ronnie Lane left the United States in July, but only to attend a reunion of the Faces. He returned to Texas in August, determined to clear his name in the suits. His vindication is not assured, although the public is forgiving, because not all of his dealings with ARMS can be explained by happenstance or ignorance. For example, Ronnie Lane received some $7000 in “consulting fees” and other payments by ARMS. Nothing in the organization’s charter—drawn up by Mae Nacol—authorized ARMS to pay his living expenses.

Ronnie Lane is now sharing a two-bedroom house with Jo Rae DiMenno in Austin’s tree-shaded Clarksville neighborhood, a quiet place, far removed from his bitter memories of Houston. He spends some of his evenings conversing with new friends or sitting in on sessions with an Austin musical group that has already played a benefit for the Ronnie Lane Foundation, the Briton’s latest organization for taking care of his needs, and probing new treatments for MS. But mainly, Ronnie Lane spends his time lifting dumbbells or exercising on a stationary bicycle and on a set of parallel bars. His physical therapy bouts are frustrating, because along with his Texas legal troubles has come the return of a problem more frightening and significant. About the first of May, as his mother would have predicted, Lane’s Iowa-induced recovery began to fade. He is back in his wheelchair again. MS has resumed its dance of debilitation, two steps forward, one step back. Lane still touts the Soll treatment for MS, just as he touted HBO as an advance in managing the disease. But his pronouncements are not nearly so convincing as his painful hours at the parallel bars are. MS has made Ronnie Lane a willful man. Ten years ago, the disease brought him down from the British highlands. Every morning he tries to get up again.