This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

I had known Paige Patterson for scarcely ten minutes when I asked him the toughest question you can ask another person. “Dr. Patterson,” I blurted, ignoring whatever we had been talking about, “what do you believe?”

I don’t know exactly what I expected, but it was not what happened. Patterson didn’t hesitate for a second.

“1 believe,” he said, “in the absolute Lordship of Jesus Christ. He is both God and man. I believe in the total sinfulness of every human being. I believe in the substitutionary death of Christ in our behalf and His subsequent Resurrection. I believe the Bible is the Word of God without any error, written to us. I believe the same Jesus will come a second time. And that about sums it up.”

I had never asked anyone that question before, because I never thought there was anyone who might be able to answer it. But Paige Patterson seemed to be waiting for me to ask, as though he had been rehearsing the speech all his life. As I read back over his response later, I realized that it should not have been surprising at all. With a few qualifications and emendations, it was a perfect credo for the American fundamentalist, who is nothing if not sure of himself.

I need to explain at the outset what I mean by “fundamentalist,” since even most fundamentalists don’t like the term. When I asked Patterson whether he was a fundamentalist, he said, “Not if you mean a narrow, obscurantist bigot.” Patterson’s use of the word “obscurantist” indicated an intention to separate himself from fundamentalists who insist on such evidences of holiness as military haircuts and abstention from motion pictures. That was not what I meant. I was speaking of fundamentalism as it was first formulated in 1909 in a series of conservative books called The Fundamentals: A Testimony of Truth. “In that case,” said Patterson, “I’m a fundamentalist.”

The fundamentalist has always had a bad press. The Fundamentals, authored by a group of scholars that included Southern Baptist theologian Edgar Y. Mullins, were a comprehensive response to the age of science and the perceived threats it had carried into the twentieth century: Darwinism, relativity, skepticism in the universities. Distributed through churches and the worldwide branches of the YMCA, the Fundamentals had a brief but important life as a reassurance to many pastors and churchgoers that science had not called all into doubt. The Fundamentals were hooted down by H. L. Mencken, able agnostic that he was, and became the subject of frequent pulpit debates between liberals and conservatives. Of much more lasting effect was the publication in the same year of the Scofield Reference Bible, the lifework of C. I. Scofield, who was pastor of the First Congregational Church of Dallas until his death in 1921. The Scofield Bible is to this day the most widely read conservative reference Bible and was reportedly the one thumped in the face of Clarence Darrow by William Jennings Bryan, the outclassed fundamentalist at the Scopes trial.

“Fundamentalists are products of the twentieth century who feel more comfortable in the nineteenth, and the banner of Victorianism is often held aloft from their own pulpits.”

Fundamentalists, then, are products of the twentieth century who would feel more comfortable in the nineteenth, a definition I use with no irony intended, since the banner of “Victorian orthodoxy” is often held aloft from their own pulpits. Such a man is Paige Patterson, a brash 38-year-old theologian whose allies are responsible for the most intense theological debate within the Southern Baptist Convention in several decades. Its outcome has relevance not only for Baptists but for Christians everywhere.

Today Patterson is president of the Criswell Center for Biblical Studies, now including the Criswell Bible Institute, which is one of the staunchest adherents to the historical fundamentalist view of Scripture. Patterson has seen to that. “We believe,” he says, “that the original autographs of the Bible represent an infallible and inerrant document that is absolutely true theologically, philosophically, scientifically, and historically.” And to make sure that the Criswell Center continues to uphold that belief, the institution asks all faculty members to sign a statement of faith to that effect.

The key word to the fundamentalist is “inerrant.” Jerry Falwell used it in his famous Penthouse interview in 1980, but the errant editors transcribed it as “inherent.” Almost any Southern Baptist would have recognized it as the rallying cry of the conservative revival within the denomination (but, of course, no inerrantist would have been reading Penthouse). The importance of the inerrancy doctrine extends to other denominations as well, including Methodism, Presbyterianism, and the two poles of Missouri Synod Lutheranism. In all these denominations, and to a lesser extent even within Catholicism, the belief is growing that unless the Bible is defended as a perfect, divine document, absolutely trustworthy in its guidance, there will soon be a wholesale disintegration of the Church as we know it. Patterson holds to this doomsday view. “It all comes down to a fundamental epistemological question,” he says, “which is, ‘How do you know what you say is true?’ Our answer is the Bible. Without it, we’re left to the shifting sands of human opinion, and no Church guided by men instead of by God can long survive.”

The Baptist Vatican Draws the Line

On the day I met Paige Patterson, he was dressed in a baby-blue Ultra Suede jacket, shiny synthetic-fiber pants, and pointy-toed boots. A thicket of red hair stood out menacingly from his broad forehead, as though it had been combed straight out from the scalp. His greeting was loud and hearty (“Come right on in here!”), but what I took to be bluster later turned out to be the defense mechanism of a man who, despite years of practice, has never become quite comfortable in social situations. Much of the time his face was fashioned into a sort of half-smile, half-smirk, accentuated by his dimples, creating the impression that he is a person who long ago made up his mind about how things are and is going to tell you as soon as you stop talking. He is folksy enough to put a visitor at ease, but his eyes betray no self-doubt and his manner brooks no ambiguity. If Paige Patterson is a modern prophet, as some of his supporters have suggested—if he is indeed on the way to becoming one of the most important theologians in American Protestantism—then he is one who comes by prophecy without the benefit of any dark nights of the soul. Here is a man, I suspected at once, whose theological worries about human weakness rarely extend to himself.

We met in his office, which is in the basement of a parking garage, part of a building once owned by the Internal Revenue Service but now outfitted as the home of the Criswell Center for Biblical Studies. Even a person intimately familiar with downtown Dallas would scarcely know it is there, hidden as it is among the spires and facades of the seven-square-block “Baptist canyons.” These are the buildings owned by or affiliated with the First Baptist Church, the world’s largest congregation of Southern Baptists, where Dr. Wallie Amos Criswell reigns over a spiritual kingdom of 22,000 worshipers, 300 staff members, 40 ordained pastors, a twelve-year school (First Baptist Academy), a Bible college (the Criswell Center), fourteen mission churches scattered around Dallas County, a radio station, a publishing operation, a health and fitness center, and $100 million worth of real estate that Canadian developers would dearly love to get their hands on. Also part of the complex and partly dependent on the church are the headquarters of the Baptist General Convention of Texas, which represents more Baptists than any other state convention, and the Christian Life Commission, its social action arm.

The Baptist Vatican, as all this is sometimes called, has long been the most stalwart champion of nineteenth-century hard-shell Baptist fundamentalism of the hellfire and damnation variety in all of America, and no doubt it always will be. It was in 1969 that Criswell published Why I Preach That the Bible Is Literally True, a religious best-seller that most theologians regarded with horror and that led indirectly to the reverend’s celebrated television confrontation with Madalyn Murray O’Hair. To give you some idea of just how literal Criswell is, he announced shortly after arriving in Dallas in 1944 that he intended to preach on every single verse of the Bible, in order, beginning with Genesis 1:1 and continuing until he had satisfactorily explained the last word in Revelation. As you might imagine, this was not greeted with universal amens among the laity. Nevertheless, he started on his journey, preaching on a few verses each Sunday morning and a few more each Sunday night, until he had finally done what he had said he would do—seventeen years and eight months later.

“Paige Patterson creates the impression that he is a person who long ago made up his mind about how things are and is going to tell you as soon as you give him the chance.”

It is altogether appropriate that Patterson’s battle lines should be drawn at First Baptist of Dallas, for First Baptist is the church where Criswell, the nation’s most famous fundamentalist (until the emergence of Jerry Falwell), has held court for 37 years, and where Billy Graham, the world’s most famous evangelist, is listed as a member. Criswell and Graham are an instructive contrast, in fact. Graham’s early career as an evangelist roughly coincided with Criswell’s seventeen-year exegesis of the Bible. But whereas Billy Graham was the world’s first superstar evangelical (even before the word became common coin), W. A. Criswell was a throwback, the world’s latest fundamentalist. The distinction looms large among some conservatives, especially those on the fundamentalist side. Whereas Graham tended toward the ecumenical, Criswell remained firmly rooted in the sectarianism of the Baptist faith. Whereas Graham used every available tool of the modern age—television, Astrodome rallies, crusades throughout the Third World—Criswell remained preeminently the pastor of a local church, more inclined to evangelize through his writing, to promote scholarship, and to found institutions that will perpetuate the faith after he is gone. To this day, they remain models of the two principal branches of conservative Protestantism, Graham the evangelical and Criswell the fundamentalist. It may or may not be significant that, at least when both men are in Dallas, Criswell is clearly the shepherd and Graham one of the flock.

There are only five people in the world who know W. A. Criswell’s home telephone number, and one of them is Paige Patterson. (“We have to do it that way to protect him,” says Patterson, “because Dr. C. finds it impossible to say no. He would literally try to minister to all twenty-two thousand church members if we let him.”) Patterson is also one of a dozen or so associate pastors who serve as Criswell’s “kitchen cabinet,” making the decisions on personnel, budget, finance, and missions that have grown ever more complex as the First Baptist kingdom has expanded. As one example, the church was a party two months ago to one of the most expensive real estate deals in the history of the city. First Baptist sold the old YMCA building and the half-block it stands on to the Lincoln Property Company in exchange for cash and a 15 per cent interest in the high-rise office building that will be erected directly across the street from the church.

But Paige Patterson’s most important function—and the reason that Criswell plucked him away from a large church in Arkansas to direct the then minuscule Criswell Bible Institute in 1975—is to develop the most comprehensive intellectual defense of fundamentalism yet attempted. The first thrust of this new apologetics culminated in 1979 when Criswell, Patterson, and twenty other conservative scholars published The Criswell Study Bible, which they hope will eventually supplant the two most popular Protestant commentaries, the Scofield Bible and the Broadman Bible Commentary (which, incidentally, was also assembled by a Dallas churchman, a Methodist). So far, the Criswell Bible has sold 250,000 copies, less than expected but more than any other modern reference Bible. The second thrust of the fundamentalist revival was to promote a college, the Criswell Center, which had been founded specifically to oppose the alleged secularism at Baptist colleges and seminaries. It has done that and more. Today the Criswell Center has some 330 future pastors studying there, more than any of the other 53 Baptist colleges except the largest, Baylor University.

None of these assaults on modern theology would have been successful had it not been for a controversy that began in 1978 and that could have more to do with the future of the Baptist religion than any other single issue. Patterson, with Criswell’s tacit assent, carried the banner of inerrancy into the arena of Baptist politics. Suggesting that Southern Baptist seminaries be purged of certain scholars who didn’t believe in inerrancy, Patterson and a Baptist layman, Houston appeals court judge Paul Pressler, set out to gain control of the boards of all Baptist schools by electing a far-right Southern Baptist Convention president, who in turn would be expected to make doctrinally pure appointments.

Patterson and Pressler have succeeded in getting their candidate elected for three consecutive years now, but each time their opponents have grown more embittered and more willing to question their motives and theology. Duke McCall, president of Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Kentucky, has accused Patterson of conducting a witch hunt. Ken Chafin, pastor of Houston’s South Main Baptist Church and chairman of the board of Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary in Fort Worth, has described Criswell, Pressler, and Patterson as “people with different sets of sick egos with different ego needs—one old one that should retire, one with a secular vocation wanting to be in a religious vocation, and one with a second-rate institution wanting to be in a first-rate institution.” Presnall Wood, editor of the influential Baptist Standard newspaper in Dallas, challenged Patterson to name names and cite examples of heresy, a challenge Patterson finally accepted by naming seven Baptist “liberals” and the writings that made them so.

Not so coincidentally, one result of all this dogfighting has been record enrollments at the Criswell Center. Most Baptists, faced with the choice of entering the twentieth century or marching steadfastly backward, will willingly execute a brisk about-face. Patterson admitted as much when I asked him whether he was a relic of the Dark Ages. “To some degree,” he said, “it would certainly be true that I’m a throwback. I love to go over to the Perkins School [the theology school at SMU] once in a while to watch the true liberals’ reaction. They love to see me because to them I’m like some kind of woolly mammoth that has miraculously survived into the twentieth century.”

No Souls Tonight

Paige Patterson was on his way to a revival in Seminole when I dropped by to talk over his theology, so I decided to go along. He met me at the airport with a rolled-up copy of the Wall Street Journal under his arm, but he only glanced at it as we sailed out over the dull brown expanses of far West Texas. The farther west a person flies and the sparser the population becomes, the higher the percentage of Baptists. Isolated country is usually Baptist country, the religion a reflection of the individualism and simplicity of the people who chose to venture beyond the woodlands and live in the open country. Before the plane descended toward the New Mexico border and the oil and farming community of Seminole, we would pass over Abilene, site of Patterson’s alma mater, Hardin-Simmons University, and then very near Rotan, where he had had his first pastorate.

One of Patterson’s students once described him as “a butterball in Swift’s Premium clothes wearing a camel grin for a face,” which is accurate enough most of the time. She should have added, though, that at any given moment he can turn intense and acerbic, even combative, in the defense of some sacred principle. He changed in just that way when I asked him about his political interests.

He had just returned from Washington, to which he travels frequently in his capacity as a trustee of the Religious Roundtable, the lesser known of the two principal arms of the religious right. Unlike Jerry Falwell’s Moral Majority, which was established to appeal directly to the public, Religious Roundtable proceeds from the assumption that the most effective political organizing is done through pastors instead of laymen, and most of its lobbying efforts take place behind the scenes. “By the time I checked in at my hotel,” Patterson said, “there were two messages from the White House waiting. They wanted me to come over so they could ‘explain’ Sandra Day O’Connor. They really had us over a barrel, because they knew we wouldn’t desert Reagan over that one issue and we didn’t have a prayer of blocking her confirmation. They made that very clear.”

At the Midland airport, a tall, blond man in his mid-thirties bustled up to us, full of nervous energy and brimming with revival news. He was Kent Atkins, pastor of the First Baptist Church in Seminole, where we were headed for night seven of a revival that had already featured such right-wing luminaries as Bailey Smith, president of the Southern Baptist Convention, best known for his “God Almighty does not hear the prayer of a Jew” statement; James Robison, the television evangelist from Hurst; and the Criswell Center’s most famous student, Rick Stanley, Elvis Presley’s personal bodyguard for 22 years, who was converted two years ago and is now in great demand as an evangelist.

We rolled into Seminole at dusk, past the town square and up to the large city block where the church buildings stood, arriving just as Wednesday night supper was ending. Patterson moved effortlessly through the congregation like a deft campaigner, shaking hands with the men and flattering the women. Slowly the crowd filtered into the sanctuary, which was outfitted for local cable TV broadcasts, and started in on four or five nineteenth-century hymns. This was obviously a rock-solid group of Baptist lifers: most of them sang without benefit of hymnals.

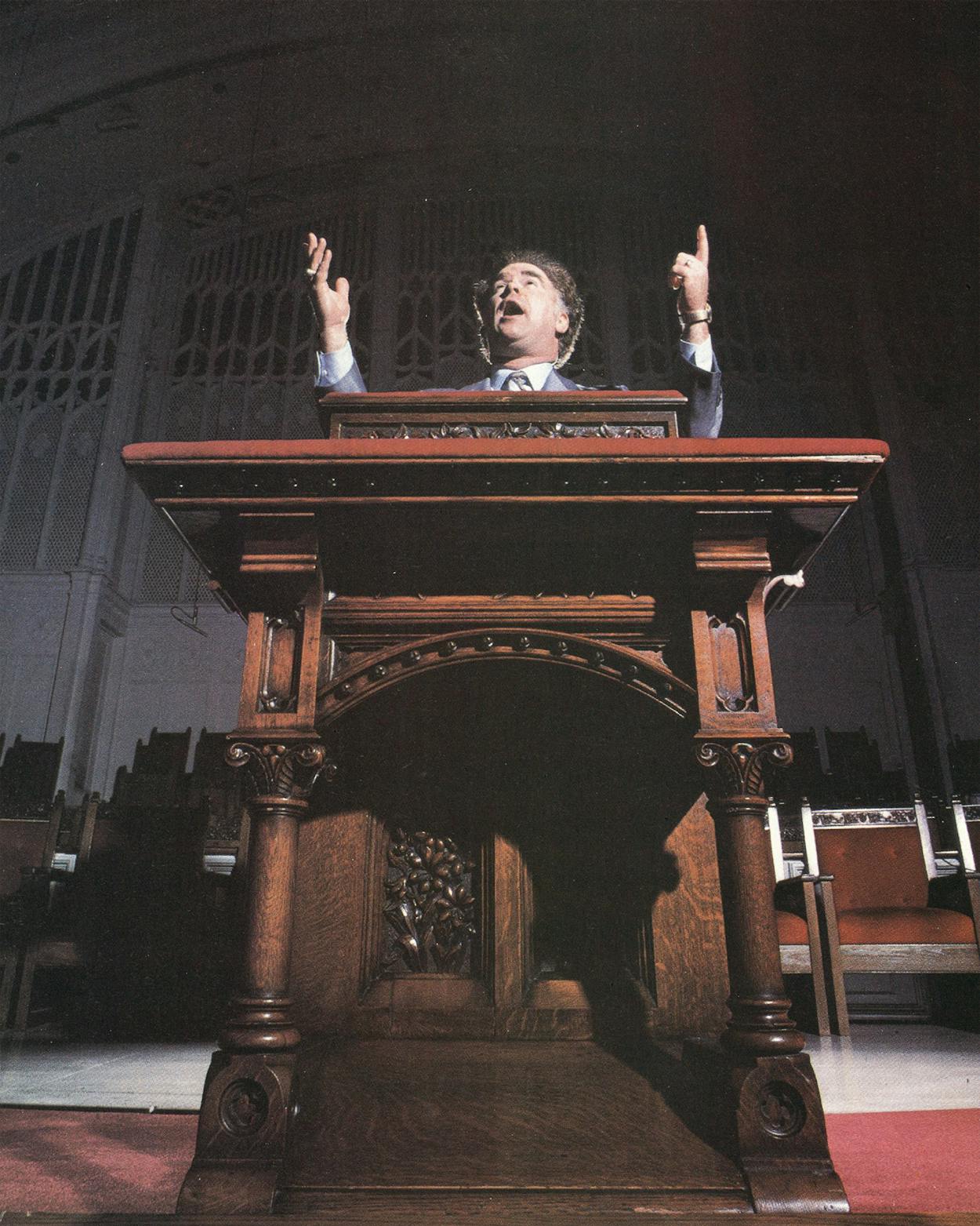

Patterson’s sermon was an eclectic mixture of personal testimony, harsh judgment, scriptural readings, occasional comic relief, and, of course, the “invitation” to the audience to come forward and be saved. Because he was speaking to a staunch, believing crowd, he chose a text from the nineteenth chapter of Mark, in which Christ exhorts the rich man to sell all his possessions and give to the poor if he desires salvation. For “it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle, than for a rich man to enter into the kingdom of God.”

Now, I have heard dozens of sermons on this same passage, but I had never heard one by a man who believes in the absolute literal truth of the Scriptures. The verse is nothing if not explicit; it all but says that heaven is not a place for the wealthy. Yet I have never heard a preacher put it quite that way. I have heard them say that we shouldn’t be slaves to riches, that we shouldn’t put money above God, that we shouldn’t let materialism govern our lives, but I have never heard them say that a rich man will find it all but impossible to enter the kingdom. Patterson didn’t quite say that either, but he came closer than anyone else I’ve heard.

“The Lord meant exactly what he said there,” said Patterson. “First you must die to yourself, die to your old way of life, and discard whatever came first in it. In this case the man’s god was money. In another it might be popularity or family; some people even make idols out of churches. God must come first, and if great possessions get in the way of that, then you must toss them aside.”

I have paraphrased his exact words because he speaks in grand cascades of language, the pitch rising and falling as he approaches the emotional climax, his pace never faltering as he pours out sentence after sentence without pause, like an AM disc jockey but with more intensity. He uses his hands sparingly, unlike wilder evangelists, and when he does he waves them together in complementary arcs, almost like a conductor coaxing sounds from an orchestra. On this night he shifted gears at the end and told one of his favorite stories, that of Charlie Miller, a punch-drunk prizefighter who boozed and brawled up and down the streets of Chicago before he was saved one night at the Pacific Garden Mission. Miller moved to Beaumont and started a similar mission there about the time Patterson was born, and even when Patterson was a boy the two were fast friends. Patterson used Miller’s story—which is a great melodrama—to illustrate the maxim he found in the Bible passage: “With man it’s impossible to achieve salvation, but with God, all things are possible.”

Patterson harvested no souls that night (a week later, at First Baptist in Dallas, his sermon drew fourteen sinners into the fold), but a few of the women wept at the Miller story and the worshipers expressed their appreciation afterwards. He had just time enough to make a few more contacts before we raced back to the airport. The visit had served a double purpose: Patterson had publicized the Criswell Center and he had exhibited, as best he could, the expository style of preaching that it represented.

The Classroom Conspiracy

The first problem you have in trying to sort through a Baptist theological debate is that the Baptists, strictly speaking, have no theology. Hence all 36,000 of the Southern Baptist churches are autonomous—a distinction they guard assiduously—and each has the right to do just about anything, even to reject the literal authority of the Scriptures. In a very real sense, Southern Baptists have one of the few religions that depend on majority rule, with each church functioning somewhat like an eighteenth-century New England town hall. This means that every theological concept of any importance must be intelligible to even the least astute layman and that any theologian tending toward obscurantism, or even intellectual complexity, increases his chances of failing to be heard. “We are and always have been,” says Patterson, “a denomination of butchers, bakers, and candlestick makers.” Indeed, half of all Southern Baptist churches have fewer than two hundred members, reflecting the denomination’s rural origins, and a majority of Southern Baptist pastors have no college degree. Yet their long-standing belief in the “priesthood of the believer”—growing out of such movements in the Reformation as the Lutheran, Zwinglian, and Anabaptist—means that the church’s true theologians are these uneducated, mostly rural churchmen.

The Baptists’ trust in majoritarianism, in simple truths, and often in anti-intellectualism has not meant that they have failed to build just as many divinity schools and Bible colleges as every other denomination. It simply means that the acid test of their theology is the local church, run completely by laymen. It also means that every Baptist theologian, to be effective, must also be a popularizer. Beliefs may be formulated inside the walls of the academy, but they must be continually defended from the pulpit.

A charge that Patterson makes consistently, in fact, is that the Southern Baptist seminaries have concealed what’s really going on within their classrooms. There are six such seminaries—funded cooperatively by the 36,000 churches of the convention—but there are only two of supreme importance. One is Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary in Fort Worth, which is simply the world’s largest seminary. The other is Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, which is the denomination’s oldest school and, according to Patterson, the most liberal. The seminary where Patterson studied, New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary, is much smaller than these two schools and is somewhat less important.

There has never been an age in which denominational seminaries weren’t occasionally visited by disputes over heresies, both real and imagined. What makes the stakes so high in this case is that, compared to most other Protestant seminaries in the world, the Southern Baptist seminaries are the Super Bowl of conservative debate. Southwestern has more than 4000 students and Southern has 2200 in a time when most graduate-level theological schools have declining attendance and enrollments averaging 200 or fewer. This is also a time when conservative churches, especially Pentecostal, charismatic, and the Church of Christ, are growing rapidly while less absolutist branches of Protestantism, such as Methodism, are dwindling in membership or holding steady. In a very real sense, the outcome of the inerrancy debate, which could ultimately result in nonfundamentalist professors’ leaving their seminary positions, could widen the gap between the secular world and the true believer.

One of Paige Patterson’s intellectual predecessors is B. H. Carroll, a nineteenth-century pastor who rode with the acutely irreligious Texas Rangers for several years before accepting the Baptist faith at the age of 22. Carroll went on to found the first Baptist seminary in the West, Southwestern in Fort Worth, and to serve as its first president. A learned man and a widely published author at the time of his death, he nevertheless lived in fear of the theologians’ triumph over the laymen. L. R. Scarborough, who succeeded Carroll at Southwestern, described a deathbed speech by Carroll that exemplifies the anti-intellectual bias of the Baptist church. Carroll supposedly called Scarborough to his bedside, pulled himself up by a chair, and said, “My boy, on this hill [Seminary Hill in Fort Worth] orthodoxy, the old truth, is making one of its last stands. I want to deliver you a charge, and I do it in the blood of Jesus Christ. If ever you find a heresy here, first take it up with your faculty. If the faculty won’t hear you, then take it to the trustees. If the trustees won’t hear you, then take it to the Southern Baptist Convention. And if the convention won’t hear you, then take it to the common Baptists. They will hear you. I charge you to keep this school lashed to the old gospel of Jesus Christ. By the grace of God, we will stand by the old book.”

“The old truth,” “the old gospel,” “the old book”—these are the things that Paige Patterson loudly defends, and they are as much a part of the social fabric of Texas as they are theological constructs. In the fifties, when my father drove a school bus in the remote reaches of the Panhandle, the students would sing songs about the old gospel, and there was never any question but that it was the Baptist gospel, the conservative gospel, the literal gospel, and the public gospel of just about the entire county. Today it would probably be a violation of federal law to sing Baptist songs in the public schools of Lamb County, but you can still find congregations out there that refuse to sing any hymn written after the year 1900. I recall hearing a sermon in the sixties at a “back to the Bible” revival in Texarkana (Baptists are always going back to something) that gave me nightmares for a week. Not until I read Jonathan Edwards’s sermons in ninth-grade English class did I appreciate that pastor’s oratorical tradition. The non-Baptist students in the class regarded the Edwards sermons with distaste, if not horror. The Baptists read the graphic descriptions of people being plunged into fiery furnaces and said, “So what?” The Baptist faith has never been one for the sheepish.

Hardin-Simmons Liberal?

Four days a week Paige Patterson teaches a nine o’clock class at the Criswell Center called “Personal Evangelism.” Unlike any lectures I’ve attended before, his are footnoted as he goes—from the Bible, of course. “One reason for our joint task of evangelism,” he began on the day I was there, “is reckoned as a portion of the debt we owe to the rest of humanity. We see this in Romans 1:14.”

And later: “Evangelism is one of the two acts when God and man join hands in creation. Those two acts are conception, the creation of a new human being, and leading someone to know Jesus Christ, the creation of a new life. Revelation 22:17 and Romans 10:14–17.”

As Patterson spoke, he occasionally stopped to take questions from the group of about 40 students (36 of them male), many of whom were referring to Greek New Testaments, all of whom were preachers in their own right. After running through all the biblical references to evangelism (some thirty or forty in all), he closed with an exhortation. “The world is growing by 172,800 people per day,” he said, “which amounts to 63 million per year. The number of Christians baptized last year by all denominations around the world amounts to only two weeks of that growth. The other ninety per cent are still lost. And every day you live, the world is more pagan, more secular, and more ignorant of the ways of God. Every single ideological system has failed these people—from Marxism to free enterprise to science to psychology—and still they don’t find God. It’s the nature of the world that gives us our strongest imperative for evangelism.”

There were scattered “amens” in the classroom.

Patterson finds it hard not to preach, even in his role as professor, and he finds it impossible to be dispassionate. He has been that way at least since the age of seven, when he told his father he had found the girl he was going to marry. Dorothy Kelley was six at the time; fourteen years later he married her. They both say they never loved anyone else. Today Dorothy is much in demand as a speaker at pro-family rallies and Christian life conferences, in part because of her book, The Sensuous Woman Reborn, published in 1976 as a Christian rebuttal to best-selling books on female sexuality. The Pattersons have three children, including a daughter adopted during their pastorate in New Orleans after her natural mother had harmed her. They lost their first child because of a miscarriage, an experience Dorothy sometimes refers to when speaking at anti-abortion rallies. “We are convinced,” says Paige, “that that was a human life and that we will be rejoined with that baby in heaven.”

Patterson grew up in Beaumont as a preacher’s kid, and like many preacher’s kids, he was extremely shy in secular environments like the public schools. Then, as now, he revered his father, T. A. Patterson, and considered him the ultimate human authority on matters of faith. He “walked the aisle” on Good Friday night, 1952, at the age of nine, was baptized on Easter Sunday, and dedicated himself to the ministry at the next Wednesday night prayer meeting.

“My conversion experience,” he says, “was very vivid. For at least three years I had been very much aware of my own sinfulness and need of forgiveness, and I wanted to do something about it but didn’t know what. Then that night an evangelist from Chattanooga named Fred Brown was preaching, and I don’t remember a single thing he said except that at the end he led the hymn ‘I Surrender All.’ And at that moment I knew what was wrong; I had not committed everything to Him. I began to weep profusely and I ran forward and threw myself into my daddy’s arms. He picked me up and put me down on the front pew and tried to make sure I knew what I was doing, but I couldn’t even speak. But he knew. Then the following Wednesday night, I went forward again to acknowledge the call to the ministry, and several of the nice church ladies came by afterwards and patted my head and said, ‘Oh, isn’t that cute, a little boy who wants to be a preacher, he doesn’t have the slightest idea what he’s doing.’ Well, they were right; I didn’t have any idea what I was doing. But God did.”

Patterson’s childhood revolved almost entirely around the First Baptist Church of Beaumont, one of the state’s largest, and the athletic fields of Beaumont High, where, as a quarterback and linebacker, he was christened “the Parson” and offered a placekicking scholarship to Baylor. But by then he was already a preacher, having delivered his first sermon at age fourteen in the Rescue Mission of downtown Beaumont to a handful of derelicts. “Charlie Miller challenged me to do it,” says Patterson, “by reminding me that if you’re committed to preaching you can’t wait around until somebody asks you. So I prepared a three-point message called ‘The Power of Choice,’ which I thought would last about five minutes; it lasted forty-five. After that my dad told me not to preach past twenty-two minutes because I didn’t know more than that.”

He also lent a hand to local Baptist causes, like the time the church rolled up its sleeves for one of the frequent liquor-by-the-drink local option elections. On election day Patterson got an old wrecked car, put it on the back end of a truck, poured catsup all over himself, and lay across the hood while a friend drove him around town. The sign on the truck read, “Finished Product of the Brewer’s Art.” His imaginative agitprop to the contrary, Beaumont voted wet. “As you well know,” he says, “the Baptists have always been involved in Texas politics, long before the Moral Majority came along.”

Prodded by Charlie Miller, churches in Southeast Texas began inviting young Patterson to preach, and he was more than willing to accept. Unlike his father (who once served as executive director of the Baptist General Convention of Texas), Paige preferred the seamier targets of the Word, especially drug addicts, alcoholics, and prostitutes. (Later, while serving as pastor of Bethany Baptist in New Orleans, Patterson opened a coffeehouse on Bourbon Street; one of his proudest achievements was the conversion of a particularly lewd strip-show barker.) He also developed a love for black churches because of the simplicity of their faith and the spontaneity of their services. While in high school, he was asked by the all-black Fellowship Baptist Church to serve as interim pastor while the church searched for a new one, a position he was willing to accept at a time when most Southern Baptists didn’t admit blacks to fellowship.

By the time Paige left for Hardin-Simmons, he had preached more than three hundred sermons, traveled to eighteen countries on a crusade, and amassed a personal theological library of four thousand volumes by working at a local bookstore and accepting books in lieu of salary. He was certain that he had ahead of him a career as an evangelist, but he wasn’t prepared for the pitfalls on the road to his college degree.

“It was time,” he says, “for my childish theological notions to grow up fast. Hardin-Simmons was probably the beginning of my concern for inerrancy, because it was my first exposure to liberal theology. For me it was very traumatic.”

Hardin-Simmons liberal?

“Absolutely,” he says. “Up to that time I felt that all Baptists were the same. Everybody had a choice, it was black and white, you chose for Christ or for the world, you were saved or lost—all of these things were my most cherished convictions. But as soon as I got to Hardin-Simmons I began to be bombarded with perspectives altogether different from everything I had learned at home and at church. They never shook my convictions, but they came close to breaking my spirit. They ridiculed the very things that I believed most fervently. For the first two years, I came very close several times to coming home. But my father talked me out of it every time.”

Sedition From the Left

“They,” of course, were the doctors of theology who, in the late fifties and early sixties, were attempting to give an intellectual framework to an inchoate religion that had grown out of a thousand tiny churches with unlettered preachers and had survived for several centuries without benefit of any transaction with other Protestant faiths. As that isolation became less practicable in the twentieth century, Baptist scholars went to other religions for the common language needed to articulate their beliefs. But at the same time, according to Patterson, they began to challenge the very beliefs they were supposedly championing.

The bull in the china shop, as far as Patterson was concerned, was existentialism—all existentialism, Kierkegaard as much as Sartre, Tillich as much as Beckett. And the most disturbing thing about existentialism was that no one could describe exactly what it was. Christians believed it, but atheists did too. It had its mysteries and its paradoxes, and it was not troubled by them. Worst of all, it seemed to call into question the truth of the Scriptures themselves.

When Paige Patterson uses the word “truth,” he means truth as in fact, certainty, and absolute. He does not mean truth in the sense of quest, leap of faith, or karma. He is a literalist, a rationalist, an eminently practical man. He believes that every word of the Bible is accessible to man’s reason and that there is no human problem without a clear, unambiguous biblical solution.

“What’s happened in the seminaries,” says Patterson, “is that the old liberalism of the nineteenth century gave way to a new kind of liberalism in the twentieth century that was heavily influenced by existential philosophy. Now, the old liberals, they were very up-front about their conviction. They simply said, ‘We believe that the Bible is clearly in error in many places. We see a lot of good moral teachings in it, but we don’t see that many of the things written in it have any truth at all.’ They were rationalistic and anti-supernatural.

“Now, along come the liberals of the twentieth century and they say, ‘Wait a minute, God really does speak through the Scriptures after all.’ It was more than moral principles. They said, ‘No, God really does speak through the Scriptures, but that doesn’t mean that the Scriptures are true. They’re only true as they become true for you.’ So that, for example, if the Bible speaks of the six-day creation of the cosmos, it’s not intended to teach us that the cosmos was created in six days. It’s just teaching us that God was behind all creation.”

Especially pernicious, in Patterson’s opinion, are the writings of Karl Barth, the colossus of Swiss-German Protestantism, who rallied Christian conservative forces in civil disobedience against Hitler and was subsequently deported. Of the several most influential theologians of this century—Barth, Bultmann, Tillich, Teilhard de Chardin—Barth is by far the most orthodox. To give you an idea of how radically conservative Patterson is, he considers Barth a liberal. “I will say that Barth really was a believer,” he says. “Some of these men, like Bultmann and Tillich, lost any real serious expression of Christianity, in my opinion. But I think if Barth had grown up in Texas he would have been one of us.”

The most troubling aspect of Barth’s writing, to Patterson, was his view of the Resurrection, which happens to be Patterson’s own area of theological interest. “Let me show you why I’m upset by that,” he said. “Barth says, ‘Christianity is a Resurrection faith. We believe in the Resurrection. This is exactly what we’re talking about in existentialism.’ But Barth was pressed on this issue at a public meeting when our Baptist theologian Carl F. H. Henry asked him whether the Resurrection was an actual event in time and history such that had the Washington Post been there to interview the resurrected Jesus, the reporters could have sat down and talked to Him like you’re talking to me. Well, when he was asked this, Barth became very angry. He refused to answer the question. You see, Carl F. H. Henry understood what Barth was saying. What he meant was that the Resurrection is an event that happens existentially in the heart of the believer. Who knows whether Jesus literally rose from the dead or not? The fact is, we can experience the risen Jesus in our own hearts.”

I asked Patterson whether he believed that something like that did happen in the heart of the believer.

“Sure,” he said, “but I think that where I would disagree with Barth is that I believe our ability to do that is dependent upon the historic fact. How can you experience a resurrected Jesus in your heart who in fact is still laid away in some grave in Palestine?”

The existentialist’s answer would be that with God all things are possible. But I didn’t think of it at the time.

It’s no accident that Patterson chose the Resurrection as one of his points of departure from modernism. The fundamentalist creed has always had five principal tenets: the infallibility of the Bible, Christ’s virgin birth, His substitutionary atonement, His literal Resurrection, and the certainty of His Second Coming. It so happens that these five principles were perceived to be the prime targets of the so-called higher-critical method, which then held sway in the seminaries. One advantage that the fundamentalists had over the liberals (as they were called then, when the label suggested no obloquy) is that the former knew exactly what they believed and could agree on a list of principles. The liberal theology had a hundred different manifestations, predicated on the premise that the essential truths of the Bible were to be found in the personal conversion experience (known only to the believer himself) and not in the biblical words except as they illuminated that experience.

To Paige Patterson, a fresh-faced eighteen-year-old arriving at Hardin-Simmons in 1961, this was heresy. He believed it then as surely as he believes it now. “I knew there were people who held those beliefs,” he says, “but I didn’t know they were Baptists.”

Spokesman for the Stone Age

On his very first day at Hardin-Simmons, Patterson was hauled into the college president’s office for fighting with an ROTC sergeant who was, in Patterson’s words, “using some words I didn’t approve of.” As if it had been an omen, that incident set the tone of his four years there. When a speaker at daily chapel suggested that the authors of the Bible had embellished the original text, Patterson grew outraged and insisted on replying publicly. When one of his professors sneered at an unlettered Western evangelist named Angel Martinez, Patterson took it personally. When Patterson discovered that some students were having beer busts in the dorms every weekend, he demanded that the president do something about it. And at the same time he continued his voracious reading. “I’ll admit that I had a philosophical predisposition at that time,” he says, “and that was that the Scriptures were infallible and completely true. I knew that in my heart, had always known it since that day when I was saved. But now I needed to prove it.”

His major theological interest then, and forever afterward, was the meaning of the atonement, partly because that is the point at which liberals and conservatives part company most radically. “I was reading people like Horace Bushnell,” he says, “who believed that the death of Christ had no objective purpose. It was just this wonderful moral example; it was not for God’s benefit but for ours. It may have literally happened, and it may not have, but that didn’t matter because it has meaning in the heart of the believer. Well, to this I had to say no. The atonement is absolutely necessary. The word ‘cross,’ which recurs throughout the Bible, meant only one thing to the people of that time, and that was death—your death. A criminal’s death. That’s what’s waiting for us, because we’re guilty. So ‘take up your cross’ means admit your guilt and die. Once you’ve died to yourself, then follow Me.

“Now, this is not very pleasant; people don’t like to hear it. That’s why they usually don’t hear it. There are at least four topics you’ll never hear sermons on, and one of them is the cross. The other three are the return of Christ, eternal punishment, and the biblical view of womanhood. The reason Baptists don’t preach on these subjects so much anymore is that we have been losing our theology; we want a cultured society to hold us in high esteem. And these are not man-pleasing messages. They are God-pleasing.”

While attending Hardin-Simmons, Patterson was called to his first pastorate, at the tiny Sardis Baptist Church near Rotan in West Texas. “The population of Sardis,” he says, “was three prairie dogs and one redheaded preacher. I couldn’t get out there except on weekends, but they were grateful to have anyone.” Later, as his reputation as a rock-ribbed, fire-breathing conservative was growing, a group of deacons from Second Baptist in Abilene came to him and told him that their church was in financial distress and their pastor was leaving them. They offered Patterson $5 a week if he would take the job. Much to the chagrin of his bride, he accepted and stayed there two years.

After graduation, Patterson went to New Orleans Theological Seminary, the most conservative of the six Baptist seminaries, where he came under the influence of a philosopher named Clark Pinnock. “That was really how I became convinced that Christian apologetics was a worthwhile pursuit,” he says. “Before I met Clark, I had always viewed philosophy as a waste of time and unworthy of a minister. If you believe the Bible, then why study man’s thoughts when we can study God’s? But Clark convinced me that philosophy is itself a sort of seeking after the Godhead and that although philosophers remain obscure personally, what they write changes the course of civilization. A reigning philosophy stands behind every heresy, because every philosophy proceeds from the assumption that man can be master of himself. That’s why we teach secular philosophy and liberal theology and existentialism and everything else here at Criswell Center. ‘Know thine enemy,’ we tell them.”

While at New Orleans, Patterson pastored a church in a Catholic neighborhood, preached in the French Quarter on Friday nights, and published the first of three books, a commentary on Titus. He also met Paul Pressler and debated Karl Barth’s Kirchliche Dogmatik with his Barthian professors. Finally, in his second year of Th.D. residency at New Orleans, Patterson was called to a major church, First Baptist of Fayetteville, Arkansas. It was a post he accepted with alacrity. His reason? “There may not be a more pagan atmosphere in all of America.”

Located four blocks from the campus of the University of Arkansas, his church of 2300 members included those from every stratum of humanity, from backwoods Ozark hillbillies to professors of advanced physics. But he lavished most of his attention on the heathen, setting himself up as a target for any Darwinian or philosopher who would have him on campus. He became the university’s favorite “spokesman for the Stone Age,” and he finally institutionalized the role. Each Thursday night he invited all unbelievers to his home for what he called the Lion’s Den, a free-for-all Socratic dialogue that attracted motorcycle gangs and adherents to the drug culture as well as well-scrubbed ministerial students.

The Final Arrogance

Patterson’s love for the snake pits of theological debate would have made him a far more fit opponent for Clarence Darrow in the Scopes trial than William Jennings Bryan. I saw him in action during four segments of American Religious Town Hall, the oldest continuously running religious program on television, taped at Channel 11’s North Dallas studio and syndicated nationwide. Town Hall uses a debate format, with a Seventh-day Adventist bishop presiding over a panel made up of Patterson, a Dominican priest, a black Methodist editor, an Adventist theologian, a United Methodist pastor, and a rabbi. On purely doctrinal issues Patterson and the priest went at each other tooth and nail, while the others seemed much more amenable to compromise. On social issues, the Baptist and the Catholic were less vocal. It was as though Baptists and Catholics were the last two religious groups in America in which the nuances of theology still really mattered. (During the breaks Patterson visited and joked with the rabbi, who was amused and intrigued by him as well as appalled. “The first time I met Paige,” he said, “he told me that non-Christians were damned. Now, sometimes we make judgments, but we’ve never been so arrogant as to say that about somebody.”)

On the day after the taping, I sat down with Patterson for a final time to go over the nuances of his inerrancy movement. It turned out that it means much more to him than a few seminary professors who may be saying things he doesn’t agree with. (Pressed on this matter, he denied supporting the removal of any specific professors, even those who have publicly doubted the authority of certain Scriptures. He even admitted that “there is really no way to eliminate liberalism without becoming some kind of gestapo, but there are ways to limit it.” He did say he would support a seminary president who decided to remove a professor who was out of fellowship, which is to say heretical. It is a fine distinction, but one that he considers important.)

More important than the teaching in the schools, though, is the preaching in the churches. Patterson believes that the liberal theology regarded as a threat in 1909, when fundamentalism was born, is now a fact, that preachers turn more and more to the topical style of presentation (“The Meaning of Honesty”) rather than the expository style (beginning with a Bible verse and exploring all its meanings), and that every denomination that has shown these signs in the past has eventually begun to stagnate or wither away.

If such dire predictions are correct, I suggested, then why does the inerrancy controversy seem almost entirely dominated by academics and pastors, in a denomination governed by lay people?

“The people that are helping us out in the states are for the most part lay people,” said Patterson. “We have had to go to them, because we have found that the pastors have not been courageous. The pastors will come to us in many cases and tell us, ‘Look, we believe what you believe, but our circumstances are such right now that we can’t get out in front on this.’

“You see, we have reached the point where even the word ‘heresy’ is anathema. We avoid it like the bubonic plague. That’s why inerrancy is important. We’re dealing with the fundamental basis of all faith, the basis without which the Church cannot survive, in my opinion. Or, to put it another way, we’re dealing with the ultimate epistemological question: how do you know what you know is true? Our answer is ‘Because the Bible is true.’ We can’t prove it absolutely, although we can prove a lot through science, archeology, and other fields. But we can say that our faith requires us to believe every word of it.

“Existentialism and liberal theology feel no necessity for this; they regard the Bible as a human work. In fact, one of the words Karl Barth uses for his theology is ‘dialectical.’ The fact that there are paradoxes doesn’t bother him at all. Now, the importance is this: if a man believes every word of the Scriptures, then there are certain mandates he cannot evade. One of them is that he is personally responsible for all four billion people on the globe. Now, if parts of the Bible are true and parts of it aren’t, then what’s to keep him from deciding that that evangelistic part is not that important? After all, it’s quite a job, and he might want to think it doesn’t apply to him.”

But why, I asked Patterson, can’t the differences between his view of the Bible and the Barthian view be explained simply as the attempts of imperfect men to comprehend eternity?

“I think maybe they can. I’m being pictured as very narrow, and anybody that’s been around me a great deal knows that that’s not really true at all. What I’m contending is that we lose all perspective if we just say, ‘Well, everybody’s good and everything’s right.’ I think if you’re going to accomplish anything in life you’ve got to have distinctions, things that you believe and that you’re committed to. Now, Baptists have always had certain distinctions, and one of them was the infallible and inerrant word of God.”

And yet many people, I suggested, believe that the problem with the Baptist view is precisely its literalness, its belief in its own infallibility, its accusatory nature, and therefore its arrogance.

“Sure,” said Patterson, agreeing readily. “People don’t like us because of, number one, our exclusivism. Number two, you’re right, our message is an accusation in a sense. But let me show you what God said to Jeremiah, which is exactly the truth. He said, ‘I have this day set thee over the nations and over the kingdoms, to root out, and to pull down, and to destroy, and to throw down, to build, and to plant.’ Now, we admit that there is a negative side to our preaching. It’s not pleasant to us. I don’t want to tell a man, ‘You’re going to hell.’ It gives me no charge at all. It’s not something I enjoy saying to him, but it’s something that I profoundly believe is true. And therefore not arrogance but love demands that I say it to him. It’s like, if you’ve ever tried to do any lifesaving, you know the first thing they tell you is that when a person is thrashing around in the middle of the swimming pool and he’s fighting for breath and you go out to save him, you may have to knock him out in order to save him. You may have to drag him by the hair of his head. He doesn’t want your help. We have to help him anyway.”

Now, that does sound arrogant, I said.

“Sure does,” said Patterson, smiling.

The Bible Wars

On the theological battlefield of today, the existential warhead is pitted against the spears of rock-ribbed fundamentalism.

Wherever two Baptists are gathered, there are always at least three opinions.

—Old Southern Baptist saying

A theological battle is now raging over two questions: what is the Bible and how is it to be used? Fundamentalists and evangelicals answer unequivocally that the Bible is the perfect Word of God, literally true in every respect, and that it is to be used as an absolute guide for all human endeavor; thus their insistence on laws opposing such biblically proscribed practices as homosexuality and their support of the big bang theory in physics. Theologians who take the Scriptures less literally, on the other hand, answer that the Bible is God’s instrument but that it has meaning only when read through the eyes of a believer. So questions of literal fact, such as the six-day creation or the bodily (as opposed to spiritual) Resurrection of Jesus, have no importance except as they are perceived in another way, which is mystical and irrational but no less plausible for being based on what most men would regard as myth.

Although the fine points of the fight are being argued within the domain of theologians, the battle spills over into everyday life in squabbles about textbooks that teach evolution and debates on homosexuality, abortion, and the role of women. Every battle has its leaders and followers, and the battle lines in the Southern Baptist church are clearly drawn.

Generals

The Right. The Baptist conservatives have Carl F. H. Henry, an evangelical scholar who holds membership in both the Southern Baptist Convention and its northern counterpart, the American Baptist Churches in the USA. He recently completed the fourth volume of a six-volume opus on the inerrancy of Scripture. Though Henry is scarcely known in Europe or in most other denominations, he is considered the far right’s alternative to the most orthodox theologian of the century, Karl Barth. Barth (1886–1968), best known for his opposition to Hitler, was a Swiss Protestant who revolted against the growing scientism after World War I and provided a systematic existentialist theology that emphasized awe, trust, and obedience before the mystery of God.

The Left. Rudolf Bultmann (1884–1976) was the German existentialist who first explained the New Testament in terms of basic elements of myth that have meaning only to the believer, thus becoming a kind of Carl Jung of theologians. Paul Tillich (1886–1965) was a German American who carried existentialism to its extreme, eventually defining faith as ‘‘ultimate concern.’’ The great seminary debates pitted Barthians against Bultmannians, but in liberal schools—such as the ‘‘divinity’’ programs at some American universities—the debate is more often Bultmann versus Tillich.

The Front Lines

The Right. The rock upon which inerrancy is based is the local Southern Baptist church, usually rural and fundamentalist, but led by such colossal conservative congregations as the First Baptist Church in Dallas (21,800 members), First Baptist in Dell City, Oklahoma (15,500), First Baptist in Houston (13,100), Bellevue Baptist in Memphis (11,700), First Baptist in Jacksonville, Florida (11,500), and First Baptist in Atlanta (8200). Closely allied with these churches are the rapidly growing inerrantist Bible schools, which are privately funded or, in the case of the Baptist Bible Institute in Graceville, Florida, funded by state Baptist organizations. Chief among these are the Criswell Center for Biblical Studies in Dallas, Mid-America Baptist Theological Seminary in Memphis, Luther Rice Seminary in Jacksonville (with the nation’s largest correspondence program), and the archconservative Liberty Baptist College and Seminary in Lynchburg, Virginia—home of Jerry Falwell’s Moral Majority.

The Left. No Southern Baptist church or school will admit to being liberal (the highly politicized argot of the denomination gives ‘‘liberal’’ a pejorative connotation), but the ‘‘moderate’’ faction is represented by First Baptist in San Antonio (10,100), South Main Baptist in Houston (6900), Wieuca Road Baptist in Atlanta (4800), First Baptist in Asheville, North Carolina (2700), and Second Baptist in Little Rock, Arkansas (2400). Most of these churches would resent the conservatives’ attacks on Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, the denomination’s oldest seminary and allegedly the most liberal (read ‘‘Barthian’’). That seminary and Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary in Fort Worth, which is the world’s largest school of theology, are the real focal points of the inerrantist debate, since continued victories for the conservatives could eventually root out non-inerrantist teachings from their classrooms. Also on the moderate side are the powerful Southern Baptist Convention agencies and boards, better known as the ‘‘Nashville Mafia.’’ These people represent the Baptist bureaucracy and control the denomination’s printing presses, educational programs, and the Christian Life Commission. And there are four smaller seminaries, listed here in descending order of influence: New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary; Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary in Wake Forest, North Carolina; Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary in Kansas City; and Golden Gate Baptist Theological Seminary in Mill Valley, Marin County, California.

Reinforcements

The Right. Nondenominational Protestant schools of all sizes and stripes have proliferated since World War II, but the acknowledged leader on the right is Dallas Theological Seminary, located just a mile or so from First Baptist Church and responsible through its graduates for many of the nondescript “Bible churches’’ that sprang up during the seventies. DTS is the second-largest nondenominational seminary in America, surpassed only by Fuller Theological Seminary in Pasadena, California. On the inerrancy issue DTS is joined by about fifty small, conservative schools, chief among them Conservative Baptist Seminary in Denver (part of a splinter Baptist denomination); Trinity Evangelical Divinity School in Deerfield, Illinois; and the Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary in South Hamilton, Massachusetts.

The Left. The five thousand or so Baptist churches in the northern and eastern states belong to their own convention, American Baptist Churches in the USA. The Southern Baptists broke away at the time of the Civil War. It should be no surprise, then, that the American Baptist convention retains a more liberal outlook than its southern counterpart, is less tolerant of the inerrantists, and takes its cues from the theologians of Colgate Rochester Divinity School in Rochester, New York. But probably the most influential school on the non-inerrantist side is Fuller Theological Seminary, which is conservative without being literalist.

Allies

The Right. Sometimes a person can be embarrassed by his friends. The far right of the conservative movement is led by Bob Jones University in Greenville, South Carolina, a school so authoritarian and legalistic that even most fundamentalists disavow its emphasis on dress codes and asceticism. Another exponent of outward holiness is Tennessee Temple College of Chattanooga, just down the road from the yellow sheet of right-wing Christianity, the Sword of the Lord newspaper, published in Murfreesboro, Tennessee.

The Left. The far left seminaries are almost indistinguishable from philosophy departments, and all of them are at universities that were founded expressly to train ministers but that, much to the chagrin of purists, have become secularized: Harvard, Yale, the University of Chicago, and Union Theological Seminary in New York.

J. B.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Baptists

- Dallas