I don’t know what was going through John Schroeder’s mind as 20,000 spectators watched him line up a putt worth $18,000 on the final hole of the final day of Colonial Country Club’s annual golf tournament, but I was thinking about my old Granny. The 25-foot putt would enable Schroeder to tie for first place and force a sudden death play-off with Ben Crenshaw. It was easily the most important putt in Schroeder’s eight years on the professional tour: although Schroeder’s yearly earnings have climbed as high as $67,000, he is considered an unknown. In contrast, Crenshaw, the young Austin High and University of Texas graduate, has won more than $500,000 since turning pro in 1973 and is considered the Jack Nicklaus of his generation. I knew what my old Granny would be thinking as Schroeder drew back his putter. She would be thinking: Miss it, turkey. And he did, by a fraction of an inch.

Granny used to think that golf was a cream-puff game redeemed only by the fact that it occupied the weekends of men who would otherwise be foreclosing on small farms and roping widows and orphans (Granny was both) to railroad trestles. Then about 1960, television introduced her to Arnold Palmer. Palmer reminded sportswriters, and by extension my Granny, of a blacksmith hammering out his trade on an anvil, and on that image the masses rose up and swallowed the game as mindlessly as they would have swallowed a new brand of shrimp-flavored almonds.

Golf had its good guys and its bad guys — Granny never cared much for Gary Player because he dressed in black and was a foreigner (from South Africa), and it took her a spell to adjust to the news that Jack Nicklaus had once been a fraternity boy at Ohio State. Golf was both childishly simple and vicariously egalitarian, so long as it was exercised, as Granny exercised it, in front of a seventeen-inch TV screen. It was a remarkable sight to walk into Granny’s tiny living room, cluttered with yellowing photographs of catfish she had caught and relics preserved from the 1936 Texas Centennial, there to find the old lady playing out her remaining weekends perched in front of her Montgomery Ward (“Monkey Ward” she called it) black-and-white set, dipping Garrett snuff and pontificating such wisdom as, “Arnie was making a run on the field till he chilidipped that wedge on fourteen.”

Granny lived all of her life in or around Fort Worth but never saw a Colonial, except on TV. When I was a sportswriter, I offered to take her, but I might as well have asked her to put on her best housedress and come meet the Queen of England. “What would I do out there with all them high-muckety-mucks?” she wanted to know. Granny wasn’t a social climber: her idea of high rolling was taking a city bus to Leonard’s Department Store’s free parking lot, catching the private subway that connected to the store’s huge basement, purchasing a spool of No. 1 thread, dining on fried perch and peach cobbler at the Leonard’s cafeteria, and returning home in time to watch Arnold Palmer’s Tips on Golf, which preceded the tournament of the week.

Once, when we were driving through Forest Park, I turned off impulsively on Colonial Parkway, which skirts the rosebush-laced fences of the golf course and circles in front of the country club’s faintly antebellum red-brick clubhouse. “You’re fixin’ to get us arrested,” Granny warned. I told her that Colonial Parkway was a public thoroughfare, the same as her own modest street. If that was so, she asked, then why did a high-muckety-muck like Marvin Leonard, the department store mogul and founder of Colonial, live there? I said that Marvin didn’t actually live at Colonial. It was true that he built Colonial and supervised its rebuilding after a series of fires and floods, but now he had built a second country club, Shady Oaks, and it was my understanding that he made his home somewhere in that neighborhood. Shady Oaks was now the club in Fort Worth. I asked if she was interested in seeing Shady Oaks, but Granny’s old eyes had wandered through the stately oaks and elms and out to the perfectly manicured 17th fairway where a group of men in Banlon shirts and straw hats were preparing to hit their drives. “It’s the most beautiful thing I ever saw,” she said.

As I watched John Schroeder miss the most important putt of his life, my heart sank in a small, permanent way. Granny had hexed him from the grave. Arnie and Jack weren’t even in the field, but I knew Granny would already have taken Ben Crenshaw to heart with the same unwavering zeal that she felt back in the twenties the first time she watched the Fighting Texas Aggie Band parade through Fort Worth. Crenshaw had that special zing. If Palmer was a blacksmith, Crenshaw was a sculptor. Twenty thousand groaned as Schroeder missed his big putt, but later, when everyone was drunk and mellowed out on a hard week of socializing and name playing, all you heard was what a great finish for a great tournament.

Poor Schroeder. I guess second place wasn’t so bad, seeing as how he won $22,800 and got to appear on national TV in the shadow of Ben Crenshaw.

Poor Schroeder.

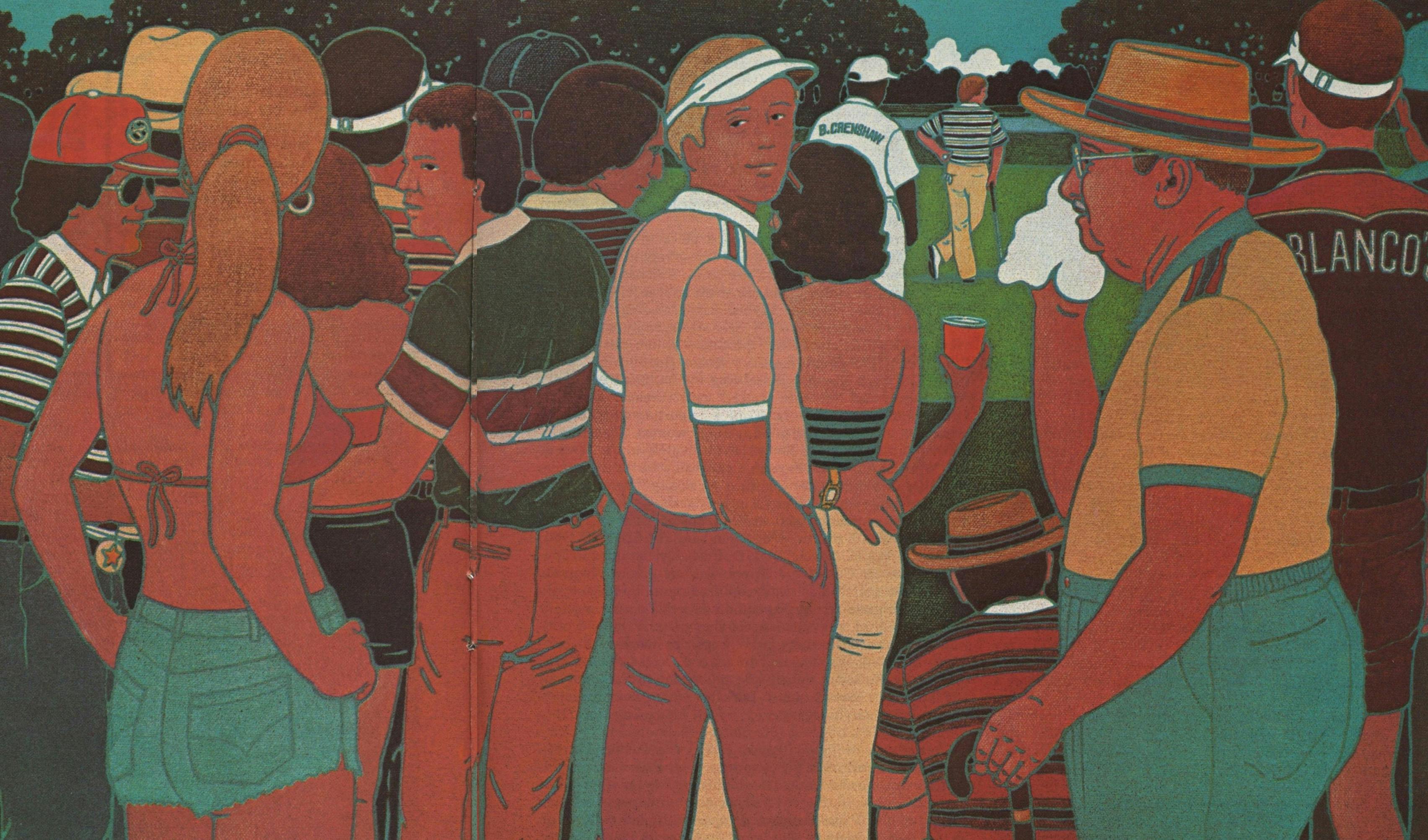

Inching along with the tournament traffic on Colonial Parkway early in May, I observed residents hawking parking spaces on their front lawns for $5. A few hundred yards from the clubhouse was a barricade guarded by a policeman who rerouted all motorists not possessing Super Saints badges. All other categories — the ordinary Angels, Patrons, club members, and plain folks with $15 tickets — were directed to the TCU Stadium parking lot where buses waited to ferry them to the golf course. There are 1600 members of Colonial, and a waiting list of six months, but only a few hundred wear the gold badges of Super Saints. Aside from the color of their badges, there is one other way to recognize Super Saints. They don’t sweat. It is an acquired art. For the privilege of playing in the pro-am, enjoying valet parking, and gaining entrance to the exclusive Terrace Room overlooking the 17th tee and 18th green, Super Saints purchased $1500 worth of tickets. Mere Angels absorbed only $750 in tickets, and so on down the pecking order. In a way, the police barricade near the clubhouse represented a final bastion separating the plutocrats from the plebeians. It was somehow sad to watch an exquisitely proportioned young woman with the word SPOILED printed on her T-shirt being turned away.

The Terrace Room is not a good place to watch a golf tournament, but it has been my observation that Super Saints do not come to watch, but to be watched. From the ground you can look up and see them cool as cloisonné behind tinted glass. In case anyone has a passing interest in the tournament, there are TV sets strategically situated in every room of the clubhouse: the Chalet Room, the Mirador Room, the Gold Room, the Cork Room, the 19th Hole, and the Men’s Card Room — these being the hangouts of Angels and mortals — all of them packed with revelers, make-out artists, and wool inspectors. Wool is a sporting-world euphemism for…well, for good-looking women. One former tournament chairman is known affectionately to the press as Old Wool. A Fort Worth doctor caught in the act of leering at a nifty in a thin halter told me: “It’s okay. I have a clearance from my wife to leer at anything above a 36-B cup.” There was an oilman who used to position himself in the 19th Hole with a prepared sign that said: TELL THE ONE IN BLUE TO TURN AROUND. Probably the most memorable scene in Colonial archives was an act of flagrante delicto near the 15th fairway, captured, quite by luck, by an ABC cameraman testing his equipment: this classic piece of photojournalism has since been shown — privately — worldwide, and the performers, who were not married to each other, are no longer married to anyone. And Cullen Davis, the multimillionaire charged with murdering his stepdaughter and his wife’s lover, used to park his trailer near the clubhouse and treat his guests to private screenings of Deep Throat.

Cullen was in the jailhouse and not available for this year’s tournament, but his estranged wife, Priscilla, star witness in the murder case, was highly visible in tight white pants and a blouse that covered the scar on her stomach and not much else. Priscilla was accompanied by her bodyguard, an off-duty homicide detective, and her presence in the Terrace Room less than a year after the murders created the kind of stir you would expect on finding Truman Capote in Gloria Vanderbilt’s shower. A few Super Saints openly greeted her; the rest openly snubbed her: there wasn’t a trace of indifference. Tom McCann, former mayor of Fort Worth and a man who himself has known adversity, sat holding Priscilla’s hand and telling her how the tournament just wasn’t the same without Cullen; though of course he was delighted to see her alive and maybe when this thing was all over everyone could get together like in the good old days.

In a sense Priscilla Davis epitomized the style and spirit of the Colonial. If it was true that the real pooh-bahs of Forth Worth now formed their alliances in the sedentary lounges of Shady Oaks, Colonial was still were things happened. CBS sports commentator Tom Brookshier, who has been around, observed that Colonial was “the halter-top capital of the world,” and Norm Alden, a former Fort Worth disc jockey who went on the become a minor actor best known for his AAMCO commercials, noted, “If you don’t like what you see at Colonial, you’re too old to be looking.” I don’t have the figures to prove it, but I’d wager that a majority of the members at Shady Oaks hold dual memberships at Colonial, if for no other reason than to be a part of the yearly rites. One of the city’s better-known gamblers was doing a few card tricks for the oilmen in the Men’s Card Room, and Hayden Fry, athletic director at North Texas State, lobbied appropriate powers on behalf of his school’s campaign to join the Southwest Conference. Willie Nelson was supposed to be at Colonial, but he overslept.

Back in the days of Ben Hogan the biggest celebrities you were likely to encounter inside the clubhouse were golfers, but that practice seems to have gone the way of all things. I didn’t spot a single golfer in any of the hangouts, not that I would necessarily recognize one. Golfers used to have names like Hogan, Snead, Nelson, Palmer, and Nicklaus — these days they are called Tewell, Cerrudo, Kratzert, Zoeller, and Curl, and if that sounds like a seat on the New York Stock Exchange my point is made. Golf is the only sport I can think of where success is measured almost entirely by how many trips you make to the bank. Where once a man had to be rich to play golf, now the reverse seems true. No less than a dozen golfers currently on the tour have pocketed more than a million dollars (Nicklaus is on his second million). When you’re playing for those kinds of stakes, who has time to sit around jabbering with local Super Saints? When you read down the list of golf’s top fifty all-time money winners you will not find Hogan, Middlecoff, Demaret, Nelson, Sarazen, Hagen, or Armour. Slamming Sammy Snead, who has made more rounds than the sun and moon, is currently listed in thirty-sixth place; a transitory footnote when you realize his undistinguished nephew, J.C. Snead, is twenty-fifth. Young Ben Crenshaw, who first attracted attention in 1973 when, still an amateur, he made a run at the Masters, has already climbed into fifty-fourth position.

Though he lives in Fort Worth, Ben Hogan no longer plays or even attends Colonial. He can’t stand the crowds. During the tournament I asked a friend of Hogan’s what the great man was doing with himself these days. “Practicing,” the friend said. “Sometimes he’ll play a few holes, alone with his caddy, but his legs won’t make it through eighteen. But there’s not a day goes by you won’t find him on the practice tee. If he hits twenty balls on the green, you can cover them with your coat.” I thought it was interesting that Hogan practiced off the tee, since that was always the best part of his game. He could drive a golf ball through the trans-Alaska pipeline and never touch metal, but position him over a two-foot putt and the dour little man would freeze. Granny idolized Ben Hogan, but of course Hogan was before television. Granny never actually met the gentleman. If she had, she might have gone back to catfishing and saved herself all those lost weekends in front of the TV.

In recognition of the fact that he has won the National Invitation Tournament, as Colonial is officially known, a record five times, and also because he redesigned several of the holes — supervising the removal of a number of trees including the big oak on No. 1 fairway that he used to hit regularly — Colonial is known as “Hogan’s Alley.” Almost all of Hogan’s trophies are on permanent display in a room adjacent to Colonial’s main lobby, but hardly anyone stops to look. Breaking one of my two cardinal rules for watching Colonial, I decided to visit the Hogan Trophy Room. As I stood there admiring a phonograph record with a sterling-silver label identifying it as “an address by Dr. Granville Walker [Ben’s pastor] in commemoration of Ben Hogan’s British Open victory, July 27th 1953,” I was suddenly aware of two young girls in shorts. They were breathing on the display glass and drawing hearts in their own fog. They asked me to get them a couple of beers. “You can sign my daddy’s name,” one of them told me. I asked if either of them had ever seen Ben Hogan, and after some reflection one answered: “I think I used to watch it on TV.”

Poor Hogan.

In the final day of the tournament I violated my second cardinal rule — I stepped outside where it’s hot and where the plebeians with $15 tickets get so caught up in looking at each other’s backs they are liable to trample you. Earlier, from the third-floor balcony, I had observed this seemingly endless stream of humanity that poured over the horizon like the Great Wall of China and had reflected on their motives: perhaps they came on the off chance that they might see someone hit a golf ball. Standing now in the crush, I realized the folly of this reasoning. Nobody who is not being paid guild wages (a sportswriter, for example) should ever take it on himself to walk on a golf course. I remembered how I hated Colonial when I worked for the old Fort Worth Press, how my main job was to roam the fairways and jot down notes that would appear at the tail of someone else’s story. I remembered how easy it was to hang close to the press room bar and let them come to me.

“…Chi Chi Rodriguez, the fun-loving Puerto Rican, delighted the gallery when he paused beside the pond on No. 1, opened a can of beans and ate them with a spoon…Rumors that Bantam Ben Hogan never opens his mouth, either on or off the golf course, were put to rest today when the Wee Ice Mon turned to Porky Oliver on the 14th green and remarked, ‘You’re away.’”

The best place to watch Colonial was, and still is, the press room, located directly above the 18th green. If you stand at the window long enough, you’ll see everyone worth seeing. There is a bar, a buffet, a roving waitress to take drink orders, a color TV, a giant leader board, a communications officer who knows instantly every bogey and birdie going down, and enough mimeographed material to fill a garbage truck. In the old days, if you wanted to talk to a certain golfer, you had to find him yourself. Now they deliver him to the press room like room service. Years ago a kid named Lehmmerman drove a cab and moonlighted as a sportswriter for the Press, but someone caught him talking to Hogan and they had to let him go. Trouble was, he was talking as he marched stride for stride with Hogan down the 18th fairway in the final crucial minutes of a tournament. He was saying, “C’mon, Ben, open up. What are you really feeling inside?”

Poor Lehmmerman.

It occurred to me as I moved along at the will of the crowd that Colonial would soon have to limit attendance. Vergal Bourland, Colonial’s general manager, later confirmed it. Colonial stopped estimating attendance in 1969 when its one-millionth “visitor” passed through the gates, but every year the crowds are larger. “I think we’ve about peaked out,” Vergal told me. “I’d guess our maximum is twenty-five thousand daily, and we must be close to that now.” Vergal noted that during the tournament there were 462 employees on the Colonial payroll, and that didn’t include 250 volunteers from the membership. Of course revenue from the tournament was staggering: $450,000 in advance ticket sales, plus the flood of bucks from food and drink concessions. The problem seems to be that the IRS is reexamining Colonial’s status as a nonprofit organization. Where once club members tolerated the tournament, now they depend on it. Colonial members pay the cheapest dues in town, one member told me. This is consolation for the fact that it is nearly impossible to use their magnificent golf course — in order to play golf on Saturday it is mandatory that club members queue up every Wednesday at 5 p.m. and draw for starting times. I don’t know if this was as Marvin Leonard intended when he opened Colonial in 1936, but given his rag-merchant proclivities, I expect it was.

Anyway, you can see why Mr. Marvin had to build himself a second country club.

Marvin Leonard is dead now, and the once great department store that he and his brother founded sits on the north edge of downtown Fort Worth boarded and abandoned like an old amusement park. During its heyday twenty and thirty years ago “Leonard Brothers’” (as Granny called it until the day she died) was the prototype of the modern shopping mall, with everything from gourmet food to overalls available under one roof. The store and its subsidiaries (one was called Everybody’s Department Store) occupied several square blocks. Marvin’s slogan, which appeared below the store logo, was “More merchandise for less money.” Leonard’s had the first escalator I ever saw, and the first subway. Mr. Marvin made his mark among retailers by purchasing enormous quantities of a single item (he once bought 50 carloads of lard from a bankrupt San Antonio grocery chain and sold it 33 cents a gallon below wholesale), using these as leads to bring people like Granny to town. Those who knew Marvin Leonard well called him the Kingfish.

“There was something magic about the Kingfish, something that inspired everyone around him,” says Berl Godfrey, Colonial’s first president. Berl recalled the Saturday during World War II when he and Marvin sat up all night watching the clubhouse burn down. Because of the war all building materials were restricted. While everybody else was throwing up their hands and bemoaning a duration without cocktails and grilled sirloin, the Kingfish slipped over to Stamford and purchased a condemned schoolhouse. He tore it down, shipped the best heavy timber to Colonial, and sold the salvage to cover construction costs.

Berl remembered why the Kingfish built Colonial in the first place. Aside from the fact that the old dairy where it is now located and the adjacent farmland that is now Tanglewood were dirt cheap and the nearest thing to a sure bet any businessman could pray for, a country club, even if it was non-profit, could generate truckloads of profits for the man who developed the land around it. But money was only one of the Kingfish’s motives. Bent-grass greens. That was his real reason. Bent grass, if you can figure out how to keep it watered and drained, stays green all year. Unable to convince the board members at Rivercrest Country Club to install bent grass, the Kingfish bought the land along the Trinity River and built his own golf club. With revenue from the slot machines that once lined its lobby, Colonial paid for itself in three years. In 1941, five years after the club opened, the Kingfish lured the U.S. Open to Fort Worth, the first time golf’s most prestigious tournament was ever played south of the Mason-Dixon line. By 1946 Colonial was a regular event on the pro-golf tour, years before Houston and Dallas became tour stops. Having Ben Hogan around didn’t hurt Colonial’s image. Nobody said no to Hogan, except the Kingfish. When Leonard decided to build Shady Oaks as a lead item for a housing project on 1400 acres of land he owned in Westover Hills, Hogan helped design the courses; but it was the Kingfish who personally supervised the bent-grass greens. Hogan finally complained that there was too much grass at Shady Oaks and built his own club near Grapevine Lake.

But of course the Kingfish was already dead.

Colonial lost something when it lost the Kingfish. Cecil Morgan, Jr., a UT basketball player from the early fifties, son of one of Colonial’s charter members and himself a current member of the club’s board of governors, recalled, “My dad wouldn’t let me play until I had first walked the course with Mr. Marvin and learned the ethics of the game. Don’t stand behind a player who is hitting…don’t stand on the opposite side of the cup when a player is putting…things people don’t always teach anymore. Even after I mastered ethics, I still had to take ten lessons from the club pro before my dad ever let me strike a ball on the course.”

By Saturday afternoon John Schroeder was making shambles of the competition and the party in the Terrace Room was beginning to look like Red Square on Lenin’s birthday. Jaded and bored by what was (or was not) taking place on their golf course, Super Saints jostled for a place at the bar and waved fistfuls of dollars at immobilized waitresses. What they needed was a miracle.

The miracle’s name was Ben Crenshaw.

There is some dispute whether Crenshaw won the tournament or Schroeder lost it; but it amounts to the same thing. Even when Schroeder was leading by five strokes and threatening the course record, Crenshaw was hovering over Colonial like a monster hawk. When Crenshaw’s fifteen-foot birdie putt disappeared in the cup on 18, Schroeder’s lead was reduced to a single stroke. “If I play a good solid round of golf tomorrow, Ben’s just gonna have to beat me, that’s all,” Schroeder said later. “This course is too tough to be aggressive. I’m not gonna do anything heroic unless I have to.” Schroeder told the press that when he teed it up on Sunday he wouldn’t be playing Ben Crenshaw, or the course, or the crowd: he would be playing John Schroeder. Considering that Schroeder’s best previous finish at Colonial was a tie for fifty-sixth place, that was a tall order.

Because the pace of the game is so amazingly slow, a golfer’s major problem is concentration: strolling from tee to green may be exercise to your average duffer, but when you are playing for these kinds of marbles it can be like a week in a nuthouse. Even golfers who have known great success can go bonkers — a few months after he won the U.S. Open, Dick Mayer woke to find himself perched on the window ledge of his sixteenth-floor hotel room wondering if he could still fly. Mayer never won another tournament. Lee Trevino copes with the long anxiety between shots by pretending he is still a ten-year-old street urchin sneaking on the Muny course after dark, using a broomstick wedged in a Dr Pepper bottle for a driver. Jack Nicklaus claims that as he hits a golf shot he images himself hitting a perfect golf shot in a movie sequence. If Crenshaw has a secret, it is this same ability to picture perfection split second before his body is required to emulate it. In his good days, Arnold Palmer used to charge the pin: it was almost like he was daring the ball to land anywhere except where he willed it. In contrast, Crenshaw seems to tiptoe toward his mark. Crenshaw grew up idolizing Palmer, but the first time they went head to head (in the 1973 Masters, when Crenshaw was still an amateur) it was like a stroll through the park. “I never thought about playing Arnold Palmer,” Crenshaw told me. “I just played the course. He shot 77. I shot 73. The next day I played with Nicklaus for the first time. I had a 72. He had 77.” Like many great artists, Crenshaw has reduced his philosophy to a one-liner: “Never do anything stupid.”

Schroeder played his “good solid round of golf” on Sunday, but it didn’t matter. Crenshaw played a little better. Schroeder started the day with a one-shot advantage, but when he faced that final putt on 18, Crenshaw had a one-shot advantage and was already in the locker room watching it on TV.

If he had hit the ball a fraction of an inch to the left, Schroeder would have forced Crenshaw into a sudden-death playoff. I’m not sure Schroeder wanted that. I know the mob in the Terrace Room didn’t.

There was a time when the most important thing to remember at Colonial was your goddamn place. No more, no more. Even the Terrace Room, exclusive haunt of the Super Saints, swarmed that last night with riffraff who wouldn’t know bent grass from Oaxacan blue. The exquisite young thing in the T-shirt that said SPOILED had finally made it inside and was drawing more attention than Priscilla Davis. I remembered another T-shirt on another body that I’d seen the first day of the tournament. It said WHATEVER HAPPENED TO HUGGING AND KISSING? and the young woman who wore it was a spastic who drooled and rolled her eyes as she lurched along Hogan’s Alley.

Nonmembers were filing out the gates now, happy it was over. So were the members, who drank with both hands and talked about wool, present and past. I could see Vergal Bourland chewing out a cop. Granny would have liked Vergal. Vergal knew his goddamn place. I remembered the night of the First and Last Annual Colonial Poolside Luau — mid-sixties would be my guess — how Vergal or one of his lackeys forgot to invite me, and how with the help of a friend I bribed a waiter out of his uniform and headed with a tray of rolls down the long hallway toward the pool. About midway down the hall, I ran into Vergal.

“What is this?” he asked.

“Rolls,” I told him.

“What for?” he asked, his voice slipping out of register.

“For hungry people,” I told him.

“Is this a joke?” he said.

I told him that hunger wasn’t a joke and never had been, then darted behind him and disappeared into the crowd. Although I was surely the first white waiter Colonial had ever seen, I walked past security as easily as the Kingfish selling Granny his recipe for possum and sweet taters. Hawaiian torches illuminated the freshly scrubbed club members who sat poolside, eating roast pig and watching as the current Miss Universe conducted a fashion show on the one-meter boards. I was headed for a table of friends when a Fort Worth cop shot me the badeye: he knew what was wrong, and as soon as he figured out what do do about it, there would be trouble. I headed straight for the ladder to the diving platform. Miss Universe and two models were using the low boards, so I said a little prayer for Granny and climbed the ladder, balancing my tray of rolls as only a man of my class could. I walked to the end of the three-meter board, paused to enjoy the show, then jumped spraddle-legged into a pool of floating orchids strung on wire spokes that hurt like hell when you go crashing through them. I ruined my wristwatch, but I got a good newspaper column out of it. I figured Vergal would have me banned for life, but when I referred to him in my column as “the long-suffering Vergal Bourland,” he laughed. Old-timers at Colonial still talk about it.

About Vergal laughing.

Poor Vergal.

- More About:

- Sports

- Longreads

- Golf

- Fort Worth