This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

One can expect only so many personal victories in a lifetime. And that is probably where I started going wrong.

Successfully escaping Houston after 25 years is one of those victories. No more fourteen-hour rush hours. No more diesel tankers thinking they are Sidewinder missiles and are supposed to run up my exhaust pipe on the freeway.

I get a nice job in Beaumont. I move to nearby Sour Lake. Dave Payne, the mayor of Sour Lake, cuts my hair (although he did raise the price to $4.50 when he got elected). My place is in the country. It’s too small to be called a ranch; it’s only a few acres. But sometimes I call it a ranch anyway.

I start listening to crossover country; even get into a little Hank Williams and the guy who plays the fiddle. (His name escapes me at the moment.) Not bad for a city kid. I get a few dogs and cats and chickens and ducks.

(Get ready, ’cause here is where I start going wrong.)

Now, it’s hard to be country with just chickens and ducks. I mean, you can’t strike up a conversation with some guy in the Lone Star Cafe and honestly say, “Oh, yeah, I got a ranch about twelve miles out of Beaumont.” That’s because the next question the guy is going to ask is “Sounds nice, what are you raising out there?”

Being an honest country sort, you’re obligated to answer, “Chickens and ducks.” Then the conversation sort of dwindles away.

Well, I’m not quite ready for cows and horses. Those things can step on you and stampede and stuff like that. Roy Rogers was always having trouble with stampeding cattle. But what about pigs?

They don’t take up all that much room and they are quiet and I’ve never heard of a pig stampede. They just lie around and eat and I’ve read that they are clean and I know they don’t cost much.

So I mention it to a few guys in the office, and two of them think it would be great if I raised a couple pigs for them. And I think it’s pretty great too because my pig won’t be lonely. And the kids think it’ll be great because of course they will have a pig of their own.

I have often reflected on how they arrived at that assumption, but it seemed quite natural at the time. And four pigs somehow seemed like the right number.

It’s a Saturday morning in March, and I’ve just about got the pen finished. I nail up the last of the hog wire on my 24-by-30-foot fence, pile the whole family into the car, throw a burlap sack in the trunk (I’ve got to get a pickup), and head off to buy the pigs.

I buy this one little piglet. I try to act like I know what I’m doing, but I’m pretty sure the guy sees right through me, and it doesn’t help having the kids cuddling the piglet and making cooing sounds.

But what the heck, we’re going to have a “working ranch” in a few minutes. The kids put the piglet in her pen, and we all lean on the fence while this little bitty piglet wanders around sniffing things. This is the way it’s supposed to be. The rancher leaning on his fence watching the stock.

“Enough of this,” I tell the kids. “We’ve got more pigs to corral.” I notice my wife is staring off into the middle distance and her eyes are a little glazed over.

We’re gone about an hour buying the other three pigs and when we get back—you guessed it—the first little piglet is gone and it’s late in the afternoon.

How did she get out? We look and look and finally see that she simply wiggled through the hog wire. My wife is now shaking her head and wandering toward the house. The kids are distraught. I get the kids to lock the pigs in one of the dog runs and I head off for the lumberyard to get some small-mesh chicken wire.

Merlin Breaux, the guy who runs the lumberyard in Sour Lake, is in real life a big-time corporate executive for a company I won’t name because I feel sure it wouldn’t want to be associated with all this. Well, I get the chicken wire and Merlin comes back with me. He doesn’t exactly ridicule the pen, but he points out that there should be a board in the middle in addition to the ones at the top and the bottom. Otherwise, the pigs will just push their way out when they get bigger.

I’m not in the mood for it, Merlin. I’ve got a lost pig, it’s getting dark, I’ve got to get this chicken wire up, and now you’re telling me I build lousy pens.

It’s Sunday morning. I let my trackin’ dogs out. One is a Doberman and the other is a slightly goofy Labrador who condescends to accompany me out into the water when I pick up a downed duck. He doesn’t feel it’s appropriate to go by himself.

But this morning they’re sniffing like crazy. Pretty soon they are on the trail of the pig. I guess that’s what they’re trailing because I see the pig tracks.

We go about a mile and I lose the trail, but I come to this fairly busy road with a wide, clean shoulder. The dogs are sniffing up and down the ditches. I’m looking to find the tracks, but instead I find a dead pig in the ditch. My dead pig. Hit by a car. I don’t even break stride. I just keep going. So do the wonder dogs. They never even see it.

Disgusted, I go plunk down another $25 for another piglet. We watch the four of them wander around. One keeps running, so we name her Trigger; another we name Elaine, after a friend. Of course we have to have a Porky, and the last one is Porkens.

Now there remains only one administrative detail to contend with. That is a method for collecting the feed bills from the other investors.

Simple enough. I’ll put out a little newsletter. I’ll call it:

The Hog Chronicles

Vol. 1, No. 1 • March 10, 1981

Our herd seems morose and listless. Expenses for feed for the first week are $12.60, which represents fifty pounds of Porky Pellets and fifty pounds of whole corn. The pigs don’t seem too fond of the Porky Pellets, but they really get off to Purina High Protein Dog Meal, which is slightly more than twice as expensive. I suspect if they get hungry enough they will start liking Porky Pellets. The dogs like them fine.

I trust that each of the investors can compute his respective portion of the first week’s bill and will be forthcoming with funds. Don’t let this turn into another coffee fund!

The Hog Chronicles

Vol. 1, No. 2 • March 17, 1981

You have probably heard over the years conflicting stories about the relative cleanliness of pigs. Some would have it that pigs are revolting, disgusting little beasts that are totally unconcerned with their appearance. Others allege that pigs are clean, tidy animals that only become sloppy because of human mistreatment. Cleveland Amory and the like hold the second position.

After a full week’s observation, I can assure you that pigs are without a doubt the filthiest degenerates ever to set a cloven hoof on the earth. They absolutely adore sticking their heads into a slop trough up to their eyeballs when they could perfectly well eat off the top. It would be like a person trying to shove his way to the bottom of a bowl of spaghetti with his hands tied behind his back.

The feed bill for the week was $7.55 for a fifty-pound sack of Piggy Starter that they seem to like a lot better than the Porky Pellets.

Do not be fooled by those who say pigs are naturally tidy; this is their real calling.

The Hog Chronicles

Vol. 1, No. 3 • March 24, 1981

Hog, Pork Belly Prices Drop as Output Rises and Retail Sales Fall

A WALL STREET JOURNAL News Roundup

Hog prices fell sharply and pork-belly contracts tumbled the daily limit on evidence that there’s more than enough pork around to meet unenthusiastic consumer demand.

“Pork production is up dramatically in the face of relatively weak supplies at the wholesale level,” said John Kleist, analyst for Bache Halsey Stuart Shields Inc. Many traders were encouraged to sell by word that 372,000 hogs were slaughtered yesterday, up from recent levels despite slack Lenten season demand.*

Now, first of all, I don’t think there is any reason to let our emotions carry us away in this matter. A little dip in the price is hardly worth mentioning. Besides, these analysts are noted for panicky attitudes and for believing any rumor. For example, look at that sentence near the end that says they received “word” that 372,000 hogs were slaughtered.

Reasonable people know that if 372,000 anythings were slaughtered anywhere, the Sierra Club, Friends of the Earth, Save the Whales, Greenpeace, and those seal clubbing people would have been wailing, gnashing their teeth, and moaning. But did we hear any of that?

One final note: I am getting a bit concerned about the rather cavalier attitude some of the investors are taking toward paying their feed bills. This stuff is starting to go fast. Our entire reserve is gone, I spent $15 on Piggy Starter, and they have gone through one sack of that. I suppose you all find this quite humorous, but the children have agreed to go without milk until Daddy can pay off all the feed bills.

*Reprinted with permission of Wall Street Journal.

The Hog Chronicles

Vol. 1, No. 4 • April 7, 1981

It is, naturally, disheartening to the writer that his failure to publish a Hog Chronicles last week went totally and completely unnoticed. What more can I say? The feed bill is $26.20, but we have three full sacks of Porky Pellets left, not that any of the investors particularly care. Why should they? It’s not their kids who don’t have school lunch money.

It appeared that until this last weekend the pigs had an aberrant fear of water. I had a nice little wallow out there for them and they ignored it. Over the weekend they discovered it. And to my own personal disgust, it looks like they’re having fun. They get in the middle, drop down on their tiny little knees, and sort of wiggle into the mud. If the mud is thin enough, they put their noses in it and blow bubbles. It all seems rather soothing and pleasant. And then they slowly flop over on one side, breathe deeply, and drift off to sleep while the mud slips off their hides back into the wallow.

The Hog Chronicles

Vol. 1, No. 5 • April 24, 1981

This is a special Hog Chronicles ACTION BULLETIN

Hog Netters Are Favored

CORPUS CHRISTI (AP) — The 66th Southwest Conference tennis tournament opens at the H.E.B. Tennis Center here today boasting field . . .

Who are these people? And why do they want to net hogs? This has to be one of the most revolting headlines I’ve ever seen in my long career of hog raising.

Now, I have never seen anyone ever try to net a hog and I cannot envision why they would want to do such a callous and wanton thing, but clearly these people should not be favored, they should be condemned! In fact, prosecuted.

If this is some sort of college ritual, I, for one, am not amused. I don’t intend to get up in the middle of the night to chase off a bunch of fraternity pranksters who are out back netting the pigs. Can’t you imagine how it would frighten the gentle little creatures? (I am, of course, referring to the pigs, not the college kids.)

At the very least, if there is some sort of ground swell toward hog netting, it should be regulated. A commission should be established to limit the size of the nets, the length of the handles, and the gauge of mesh.

Don’t sit around and wait on this. Write your state legislators today.

The Hog Chronicles

Vol. 1, No. 6 • May 7, 1981

In my haste to publish last time because of the breaking hog netter story, I neglected to make an attempt to collect feed bills. Not that anyone is concerned, but the feed bill for the last two weeks is $39.30. The kids said to tell you that they think their shoes will last until school’s out, and of course they don’t really need shoes for the summer. I’m sure that will be a relief to those among the investors who are so far behind in their feed payments that they will probably have to apply for a block grant to eliminate the debt.

I want to focus for a moment on hog calling, which is, as you all know, an integral part of hog farming. Now, I began hog calling as soon as I got the little piglets two months ago. I started with a somewhat raucous “Woooo-sooiie-pig-pig-pig,” which not only looks ridiculous on the printed page but made me check to make sure no one was watching before I did it. It seemed a bit ostentatious since the pigs were only twenty feet away. So I started using a shorter, less personally embarrassing version. It was: “Here, pig, pig, pig.” I felt that this call, done in clear English, was much more sophisticated, although rather redundant. Therefore, I have shortened it to “Here, pig,” which seems to do quite well.

I am open to any hog calling suggestions you may have.

The Hog Chronicles

Vo. 1, No. 7 • May 12, 1981

I must make a brief rejoinder to those among you who are attempting to introduce collegiate advocacy into hog farming. Sure, for some of you hog calling is easy, but not all of us are blessed with such natural talents, and I take offense at the suggestion that I should borrow a plastic Arkansas Razorbacks hog hat to make the pigs more docile. Also, I will not be duped into believing that a plastic hog hat is the “stately and respected emblem of a true hog devotee.”

Never once have I seen a hog farmer (I actually prefer the term “hog rancher”) wearing a red plastic hog hat. I mean, I go into Sour Lake almost every weekend and there has not been a single instance of hog-hat wearing. Not even at the barbershop.

The feed bill for last week was $19.65. If even one of you would pay up, perhaps I could buy the kids pencils for the last week of school.

The Hog Chronicles

Vol. 1, No. 8 • May 28, 1981

It appears that more comes out of a pig than goes in. I am at a loss to explain this, but each one is eating fifty pounds of food a week, yet to look at the ground you would assume it was a hundred. Do you have any idea of the stench now that the weather has turned hot? What’s more, I have to spray twice a week to keep the flies down. Do you know what it’s like tiptoeing around in that pen past mounds of this and that? None of you realize how big those hogs are getting. They weigh close to 150 pounds. And they bite your feet. It’s true. I have to kick them away. And I had to nail the gate shut. They were pushing their way out. It’s absurd. A perfectly good gate nailed shut. I have to climb over the fence to get in and out. I’m telling you, the whole thing is getting out of hand. They’re rooting under one side of the fence. I keep cutting stakes and pounding them into the ground with a sledgehammer. The hogs eat the stakes. I pound in new ones. The next day they are gone.

The feed bill for the last two weeks is $13.10 per person. Believe me, it’s not worth it.

The Hog Chronicles

Vol. 1, No. 9 • June 2, 1981

I hope you will pardon a digression this week, but there is an area we often overlook in the haste of daily life. We fail to reflect on our forebears and the monumental struggles they went through to make this country what it is. Particularly the hearty country folk, for whom I am developing a new and lasting appreciation. They toiled month in and month out to make a living from the land. They had no tractors. A horse was a mainstay. No wonder people were hanged for horse stealing. And then there are the little things you don’t think about until you live in the country. Hoeing weeds, cutting firewood, chicken lifting. I never thought about chicken lifting.

But I got some new chickens and chickens are funny. No, not funny—stupid. In the evening, the older chickens that I have had awhile go into the chicken coop, hop up on the nesting platform, and jump up to the roost. But these new chickens aren’t big enough to get up even to the nest. So as it starts to get dark these young chickens mill around on the ground and whine piteously. That means every evening I have to go out and bodily lift them up to the roost. But do they appreciate it? Of course not. They peck me and beat me with their wings. It’s a terrible ordeal. So you ask, “Why not put the roost down lower?” Because the chickens on top (how to put this delicately?) do more than sleep at night, and that would make the chickens underneath nervous.

However, the details are unimportant. The point is that we should have more respect for those who came before us and tamed this land.

The Hog Chronicles

Vol. 1, No. 10 • June 24, 1981

Because of a lack of developments on the hog front, I was considering going into summer reruns. However, my razor-keen mind just figured out that if I do that I will not have a vehicle for invoicing members (for whatever that is worth). Okay, you deadbeats, you owe $24.55 each and that will carry you through this week.

Now, for those of you who allow small children to read the Hog Chronicles, I suggest you snatch it away from them at this point. The time has come to discuss a most distasteful subject: the ultimate demise of the hogs. This is not as easy as it sounds. There are difficulties ahead. If you consider that a couple of the hogs are heavier than I am, the simple matter of transportation to the meat-packer is a difficulty.

I did go to the bookstore and pick up one of these “You Can Survive on the Farm When Bad Times Come” books. I found a section on slaughtering pigs. You would not believe what they would have me do to these docile critters. I will go no further than to say it involves a very long, very sharp knife. It’s absolutely repulsive. The people who write these books may survive on the farm when bad times come, but I surely will not.

One member of the cooperative has suggested that we starve the pigs. I find that to be a bit counterproductive. Another suggestion was to poison them. In that case, I fear certain ramifications farther up the food chain. I am open to any other suggestions.

The Hog Chronicles

Vol. 1, No. 11 • July 17, 1981

Picture, if you will, a tranquil scene of green water in a mirrorlike stillness. Moonlight and the stars reflect off the water. The faintest of breezes slips out of the southeast. Surrounding the pond are pines, oaks, beeches, and hickories, all adding their scents to the air.

As one’s eyes become accustomed to the semidarkness, previously invisible images start to materialize. There is one image that begins to stand out—silverish and bulky, it protrudes from the calm water.

The eyes wander up through the faint swaying of the pines to the staring moon itself. Then the eyes wander back down to the silver thing.

It’s their water trough!

They’ve taken their water trough, nudged it out into their now flooded wallow, and turned it upside down. There is no telling what kinds of vermin and pestilence are between me and the water trough. (I need to point out that this happened subsequent to their ripping the end off the feed trough and apparently eating it because I can’t find it anywhere, but it happened prior to my discovering that they like to eat the feed sacks as well as the feed in them.)

A sour and slightly copperish taste coats the mouth as one wades through what cannot adequately be described, only endured.

The water trough is cleaned, rinsed, and refilled.

The hogs are going next week.

The Hog Chronicles

Vol. 1, No. 12 • August 12, 1981

First, look at the palms of these hands. The fingers can hardly hit the typewriter keys. All the hide that’s missing off the palms and fingers is missing because of rope burns. And it all started so innocently. It was like this:

A friend calls and offers to give us a $5500 racehorse. It’s free! Now, why does someone want to give away a valuable racehorse? You got it. The horse loses—not just a little. It always loses.

So what. The kids will have a nice time with him and he’s free.

Now, after buying a thousand dollars’ worth of fence and making part of the barn into a stall, after working till ten every night to get the fence up, I take a day of vacation to go pick up Doo-da (actually his registered name is Rodson—pretty uptown, huh?—but I’m going to call him Doo-da). Quick trip over near NASA, load him up in this horse trailer I rented, bring him back. Dump him, load up the pigs, and take off for the place where they do you-know-what to the pigs. I’ll be finished by five, have a drink, eat a leisurely supper, watch the tube for the first time in weeks, and drift off on the couch.

At four o’clock I’m still trying to get this stupid half-ton beast in the trailer. I’m cut up and bruised; so is the horse. No wonder he lost all these races—by the time they got him to the racetrack, the jerk was exhausted. He’s broken this rope that’s hanging off the thing that fits over his head. It’s called a lead, as in “You can lead a horse to the trailer, but you can’t make him go in.”

Finally, with the combined efforts of half a dozen people, a guy-who-knows-what-he’s-doing, fifty feet of rope, and a bullwhip, the horse is in the trailer. Then the guy-who-knows-what-he’s-doing wants to unload him and load him again. He’s got to be nuts! I tell him that this horse will never see the inside of a trailer again. But all these “horse people” tell me, “Oh, yeah. You gotta do it again so the horse can learn.” I’ve damn near got a dead horse on my hands as it is, but I crumble before the vast wisdom of the horse people.

So we reenact the loading with just about the same results.

We get home and unload him, the kids lead him off to munch on the front yard, and I’m to the easy part. See, I’ve cleverly not fed the pigs all day. I’m going to take the feed bucket and lead them into the trailer.

Wrong!

They’ll have none of it. It ends up with ropes around the neck and back leg. Dragging one, screaming, to the trailer. Lifting a fighting 240-pound pig into the trailer. And after the other two see what’s happening to the first one, they don’t want any part of it.

Exhausted, my breath coming in great gasps, I finally tackle the last one. (The girls are feeding the horse and making soothing sounds and ignoring all of this.) The pig’s screaming, I’m screaming. I don’t care about getting him in the trailer. I’m a little crazy and I’m trying to punch the pig out. That just makes him screech louder. Good, that’s fine. Finally, my wife and boy drag me off the pig and I’m screaming and cursing the pig, trying to kick him as they pull me away.

I think some of the hams may be bruised. I fall into bed at eleven-thirty. No supper. The final feed bill is $19.65.

The Hog Chronicles had to end there because the lady who types the finished version of the newsletter told me she didn’t want to get into the gory details.

The folks who did the butchering said they were fine-looking pigs. I guess they should know because they gave me the heads back with the sausage, ribs, chops, and hams.

What am I and my other pork investors to do with three pig heads, I ask. (I guess I need to explain here that the demented pig named Trigger didn’t go to the packinghouse because she was about thirty pounds lighter than the others from all that running around.)

The meat-packing folks explain that I can make hog’s head cheese out of them.

Quickly, I point out that I can’t let the kids see these pig heads. I don’t know how to make hog’s head cheese. I wouldn’t eat it if I did, nor would anyone I have ever associated with eat it.

Oh, that’s too bad, they say. They’ll keep the heads and make them into cheese and sell it and won’t even charge me for this act of mercy.

Groveling in gratitude, I thank them and disappear toward the house.

In the freezer for 86 cents a pound, I tell my wife proudly.

She ignores the comment and asks me what I’m going to do with Trigger. I ignore her comment and point out that we are nearly self-sufficient in vegetables, pork, and eggs.

She asks what I’m going to do with Trigger.

Cleverly, I change the subject by saying that some of the Hog Chronicles readers are greatly saddened by the newsletter’s passing. I tell her that I’m thinking of doing a newsletter about Doo-da. I’ll call it the Doo-da Reader.

She asks me what I’m going to do with Trigger.

Trapped. I explain insightfully that Trigger and the horse are getting along very well and it would be a shame to break up this developing relationship.

She points out that it is rare for a horse to have a pet pig.

I agree.

She asks me what I’m going to do with Trigger.

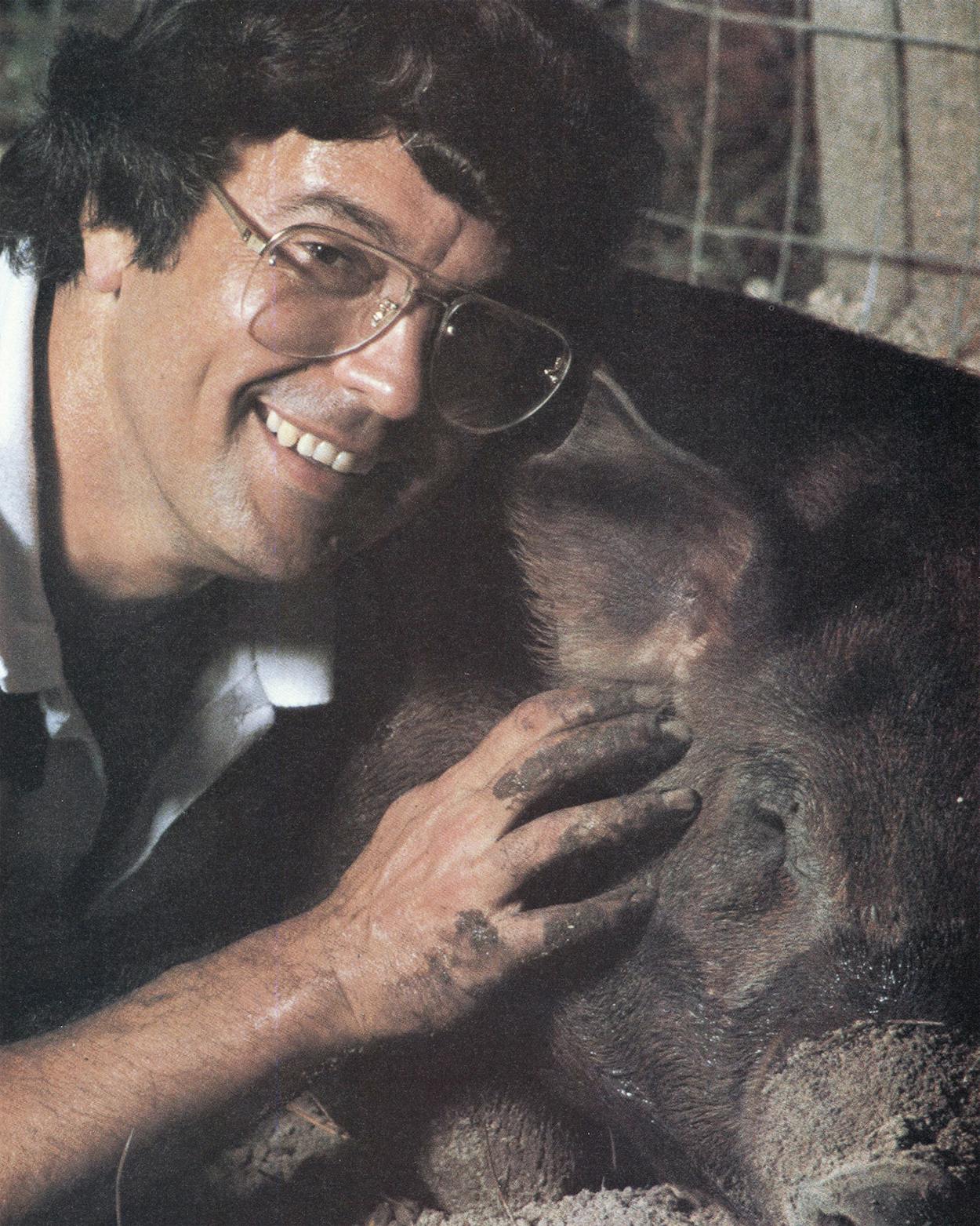

David R. White is a writer, a public relations executive, and a hog rancher.

- More About:

- Critters

- TM Classics

- Longreads