This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Ouida Caldwell is just crazy about blue. Her whole house is done up in it. Blue paint, blue paneling, blue curtains and shades. Blue brick on the hearth in the den, blue braided rugs, blue plates in the blue kitchen. More than enough blue, in other words, to lend credence to the cross-stitched wall hanging —in blue, of course—declaring Ouida’s North Dallas tract house “My Blue Heaven.” Almost the only exceptions to all this blue are red plastic flowers on the front porch and Ouida’s Mary Kay office, which is a glowing pink.

Petite, a bit wide, and well into middle age, Ouida Caldwell has for fifteen years been feathering her family’s nest with income earned from selling products and directing a sales force for Mary Kay Cosmetics, Inc., the Dallas-based direct-sales company. Besides being a corporate empire in its own right—last year’s wholesale volume was $53 million—Mary Kay Cosmetics has probably done more for Total Womanhood than Phyllis Schlafly and Marabel Morgan combined. Ouida is one of about 200,000 women who over the last sixteen years have purchased Beauty Showcases (which currently cost $65), along with a few hundred dollars’ worth of merchandise, and set themselves up as “consultants” with Mary Kay. Currently the forces of Mary Kay comprise about 46,000 saleswomen in the United States, Canada, and Australia.

On a clear, black night last winter Ouida had her blue heaven ready for a Mary Kay Beauty Show. A hot-pink card table was set up in the corner of the den, on which sat a Styrofoam palette, a mirror, and a flip chart. Nearby, on a counter, was Ouida’s Mary Kay Beauty Showcase, from which she would draw the creams and oils and liquefying powders for mixing up another pretty face.

I was Ouida’s customer. By chance the night I had requested for a facial coincided with a weekly unit meeting of the saleswomen Ouida supervises. Soon the girls (in Mary Kay jargon, women are almost always girls, sometimes ladies, almost never women) began drifting in: Pearlena, tall, black, and angular; Georgia, fresh-faced, about 35, and a graduate of Baylor; and Peggy, pert in a black pants suit with a large gold pin spelling Mary Kay across her shoulder. Several other women arrived while Ouida began her demonstration.

With the pace and inflection of a first-grade teacher, she began by telling me the story of the hide tanner who developed the original Mary Kay formula. The facial began with the Basic Set ($27.50): cleansing cream, freshener, mask, night cream, and makeup base. Then Ouida guided me in the application of the Glamour Set ($22): rouge, eyeliner, eyebrow pencil, mascara, lipstick, and eye shadow. Lip gloss, colognes, and the like are sold separately as boutique items. By now the women in Ouida’s den had just about lost interest in my progress and were talking among themselves. I felt sorry that Ouida had lost control of her group, so as she helped me with my choice of eye shadow—we eventually went with plum—I tossed out some sure bait by casually mentioning my first experience with Mary Kay.

“As a matter of fact,” I said, “I had my first Mary Kay facial ten years ago. I was in college in Waco at the time and needed makeup because I was in a beauty pageant.”

“Oh,” Georgia interrupted. “Were you a Baylor Beauty?”

I blushed, and murmurs rippled through the group.

“Ouida!” Georgia cried. “This is important!”

With this, Ouida once more had everyone’s attention. I refrained from adding that the Mary Kay set had made my face break out and that I had only been a finalist in the pageant after all.

“Women come to me all Vogue on the outside and vague on the inside. When one of our girls has a good week, we pat her on the back, put a ribbon on her, sing her a song, anything to give her recognition.”

For the average Mary Kay consultant, being a college beauty queen is one of the few possible achievements in life. Instead of seeking recognition in the larger world, women like Ouida Caldwell order their lives according to the sentiments illustrated by an antique print hanging in her blue guest bathroom. Titled “The Six Greatest Moments in a Girl’s Life,’’ it lists each with a Gibson girl illustration: the Proposal, the Trousseau, the Wedding, the Honeymoon, the First Home, the First Child. The hidden catch to this agenda, of course, is that these events—assuming they happen at all—usually take place in a span of about five years early in female adulthood. What about all the time that follows? The women entering Mary Kay have often found those long years wanting; one consultant described her precareer condition as “middle-America housewife blues.”

Traditional women, like the majority who populate the Mary Kay sales force, have found it difficult to fulfill themselves—or, for that matter, even to earn money—without fearing they might upset the very foundation of their lives. Their homes and families are valuable to them and they don’t want to give up their roles as homemakers to go to work. But rarely can a woman find a job that she can base in her home. The Mary Kay consultant finds that she can have her cake and eat it, too. With energy and organization she can keep her family together and pursue a course toward confidence, achievement, earning power, even glamour and considerable wealth. About a thousand women have positions of leadership in Mary Kay. To enter management, a Mary Kay consultant (the company term for saleswoman) recruits new consultants to form a “unit.” If she and her unit meet and maintain certain recruitment and sales quotas, she becomes a sales director. As her unit produces offspring units, she moves up to senior sales director. (Ouida Caldwell has advanced to this level.) At the top of the company’s sales organization are the national sales directors, whose offspring have had offspring. These highest achievers earn as much as $100,000 a year.

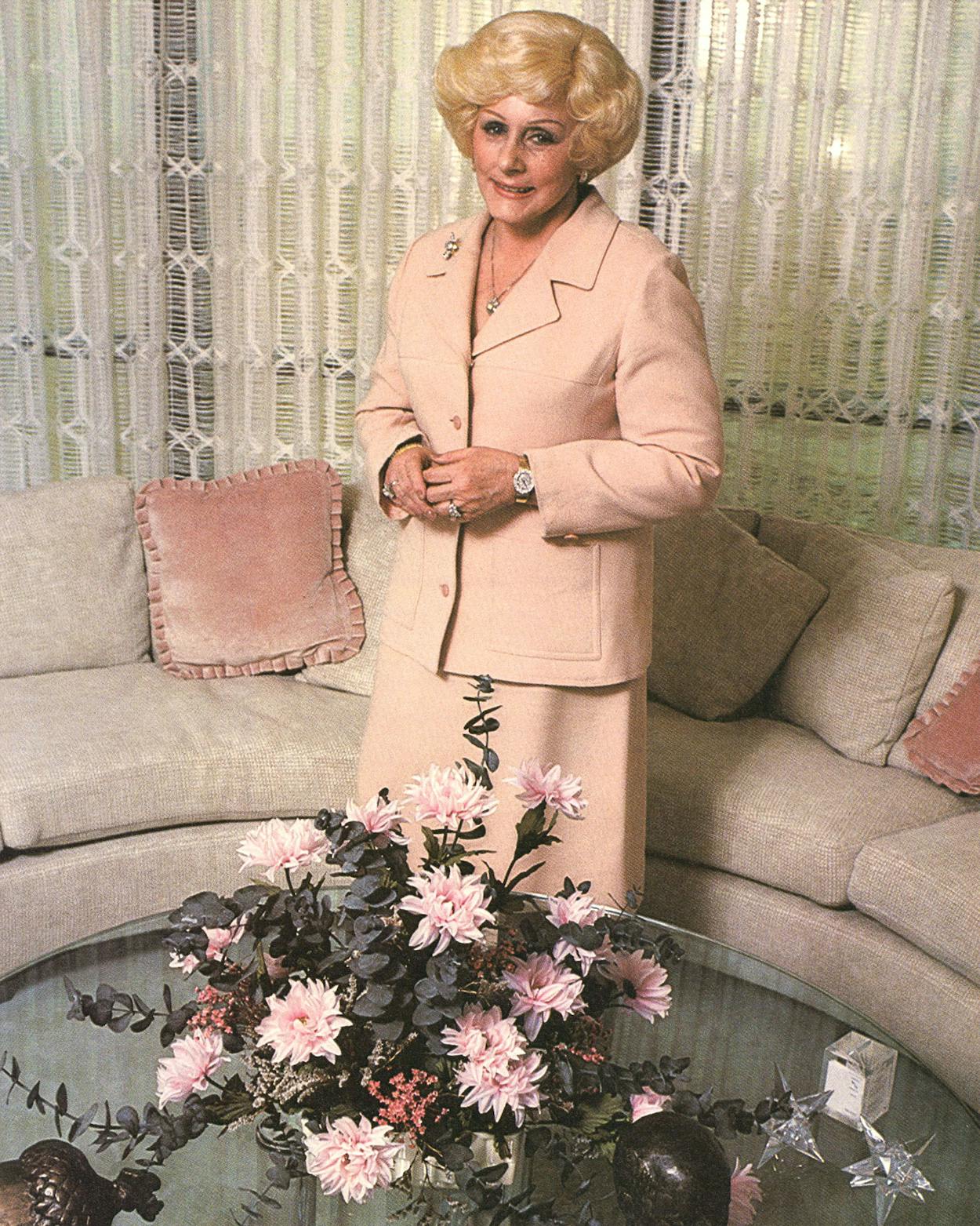

For everyone in Mary Kay’s sales force—except the handful of male consultants and directors—Mary Kay Ash herself is a living, breathing role model. Each day she dresses in a tailored suit and heavy diamonds and drives to work in a custom-designed pink Biarritz Cadillac with thin red racing stripes. Reigning over her cosmetics empire in an office that could double as Marie Antoinette’s salon, she represents the ultimate in success to thousands of her followers.

The story of her life, as Mary Kay tells it, has the ring of a romantic legend. Mary Kathlyn Wagner was born inauspiciously and in poverty in Houston sometime in the second decade of this century (her age is kept secret), the child of an invalid father and a handsome mother. She began at age seven to cook, keep house, run errands, and look after her father while her mother worked from 6 a.m. to 8 p.m. as a restaurant manager. But penury wasn’t the only thing that helped form Mary Kay. It was the strong example of her mother, who instilled in her daughter the still-rare notion that a woman can do anything she sets her mind to. Each day, by telephone, Lulu Wagner gave her little girl encouragement and instructions on getting around Houston on the streetcar to run her errands. Mary Kay talks of her trips downtown to buy clothes—getting off at the Rice Hotel, going to the store where she inevitably had to explain to clerks why she wasn’t accompanied by her mother, finally purchasing her 98-cent dress, then topping off the morning with a pimiento-cheese sandwich and a Coke at Kress’s five-and-dime.

After high school Mary Kay married a studio musician at a local radio station. Together they had a daughter and two sons, but that was about all: he was drafted and drifted out of his family’s life, and the marriage eventually broke up. Mary Kay went to work, a decision based on necessity, not on the ease and boredom that often prompt a housewife to find a career today. She decided against an office job and went to work for Stanley Home Products, a direct-sales outfit.

At first, Mary Kay was barely able to support her family, but after attending a Stanley convention in Dallas she did an about-face. Two events at the convention—watching the crowning of the “queen of sales” and meeting Stanley Beveridge in person—affected her like a faith healing at a tent revival. Mary Kay’s sales volume began to increase, and, as her career with Stanley began to take off, she moved to Dallas and bought her first home.

The years passed, her children grew up, and Mary Kay moved from a top position with Stanley to become national training director for World Gift, another direct-sales company. Even as an executive, she found herself frustrated in what was then still very much a man’s world. “I was constantly being told,” she says, “ ‘Oh, Mary Kay, you’re thinking female.’ And inevitably, no matter how hard I tried, no matter how well I did my job, I still found myself reaching the golden door only to find it marked Men Only.”

In 1963 she left World Gift and married George Hallenbeck. They were living comfortably in the Park Cities, but Mary Kay found herself restless and began to plan her own direct-sales company in partnership with her husband, who had a background in business. The product she decided to mass-market was the line of cosmetics she had been wearing for several years, and she proceeded to purchase the formula from the woman who had been selling it privately on a limited basis.

One morning at breakfast, as he was reviewing the final papers for the founding of Mary Kay Cosmetics, George Hallenbeck slumped over, dead of a heart attack. Richard Rogers, only twenty at the time, volunteered to fill in for his stepfather and take over the business end of the company, and Ben, the older son, pulled out his savings passbook and offered the $4500 in his account.

Having twenty-year-old Richard in charge of her books represented a considerable risk for Mary Kay. But she took it and, with Richard Rogers continuing to run the business and Mary Kay the sales force, a remarkable symbiotic corporate relationship has developed. Taking on her son as a partner may have been the smartest decision of Mary Kay’s career. Rogers grew to business manhood rapidly, steering the company along a low-overhead course that allowed it to be profitable for its shareholders and sales force alike. Consultants and sales directors buy merchandise at half the retail price, and sales directors get a 9 to 12 per cent commission on their units’ wholesale sales. Rogers was smart enough to know the costs of dealing in credit, so he established a cash-only policy for the purchase of inventory. And by the time the company built its new offices on Stemmons Freeway, Mary Kay Cosmetics was in the position to pay cash for the $7 million cost—“down to the last paper clip,” Rogers says.

Why would a young man enter a risky venture with his mother in the first place? “I worshipped the ground she walked on,” he says, without a glint of sentimentality. Rogers explains he and his mother never had a typical mother-son relationship. Around the time he was twelve she took the job with World Gift, which meant traveling around the country two or three weeks a month. She wasn’t about to leave a teenage boy around the house alone, so he went to Allen Military Academy in Bryan. Rogers found that the distance allowed him to see his mother as a remarkable woman. His older brother, Ben, was with the company in the beginning but eventually left to manage his own investments. He lives in Dallas. Marilyn, Mary Kay’s daughter, lives in Houston with her husband and has children and grandchildren of her own.

A key ingredient in the Mary Kay sales formula is its approach to potential customers, which is based on the belief that the modern American woman is too sophisticated for the standard door-to-door peddler atmosphere of direct sales. Mary Kay, instead, developed the home-demonstration concept. Consultants are encouraged to book five Beauty Shows a week, but the typical consultant holds one or two. (She makes about $500 a month; the typical director makes about $1000.)

“We’re in the business of people, not cosmetics,” Mary Kay contends, but the product has proved an excellent choice. Because they are small, the cosmetics are easily handled and stored by the consultants. Also, the Mary Kay line has been limited to about 45 products, compared to the 700 or so sold by Avon. Of Mary Kay’s total retail volume, about half comes from the sale of the Basic Set.

The real reason for the success of the company, however, has been Mary Kay Ash’s insight into the psychology of bedrock American womanhood and her ability to use that insight to tap a vast potential labor market: the young-to-middle-aged homemaker who is reluctant to leave home to go to work but who wants some kind of career.

First and foremost in the Mary Kay scheme, the company refuses to threaten the family structure. “God first, family second, career third” leads the long list of homespun company mottoes. Mary Kay virtually orders her troops to be good wives and mothers before they are good saleswomen. Husbands are offered “Mr. K” classes to instruct them in what their wives are going through, what they can offer (a little help but not too much), how to adjust to the changes brought on by a Mary Kay career, and, especially, what benefits to expect. Each month the company newsletter, Applause, features a “Husband’s Corner,” which is usually a letter of fulsome praise, such as this one from Ken Brock of Nixa, Missouri, published last November:

Once upon a time there was a very shy woman with no confidence, who drove to the same building, sat behind the same oak desk, answered the same blue phone, and typed on the same typewriter every day. She was never appreciated, never thanked, but was expected to do more for less. Then . . . in the midnight of lost dreams, a new little star began to twinkle. Show by show, facial by facial, a star was born. . . . The shy insurance underwriter of a year ago is my beautiful wife. She is full of enthusiasm, confidence, goals, and a beauty inside and out that could only be inspired.

Inspiration is, of course, the key to any career in sales. And the first thing Mary Kay does to motivate her forces is to give them the confidence they seem to need so badly. “Women come to me,” she is fond of saying, “all Vogue on the outside and vague on the inside. We praise women to success. When one of our girls has had a good week—even if it is something pretty small—we pat her on the back, put a ribbon on her, sing her a little song, anything to move her on to the next level.”

Women will work for recognition, says Mary Kay, when they will not work for money. Each issue of Applause lists scores of names of that month’s achievers. And beyond recognition, and the healthy commissions that come out of the company’s pocket instead of being skimmed off the sales of consultants, Mary Kay dangles in front of 46,000 matte noses a staggering array of bonuses: diamonds, gold, mink, dream vacations, and—what she calls “every woman’s dream”—the chance to drive the company’s chief status symbol: a powder-pink Cadillac. Currently the fleet numbers more than two hundred, including those leased by the company and awarded temporarily to high-volume saleswomen and those the winners have later decided to buy. All awards are based on meeting various quotas—individual sales, unit sales, number of recruits, and so on. The only exception is the monthly selection of Miss Go-Give Spirit. Because there are no sales territories in Mary Kay, there is a fair amount of squabbling over customers and recruits—enough to prompt repeated emphasis on the golden rule in company literature and the establishment of the Go-Give award for sales directors whose actions most exemplify its meaning.

Acquiring what the company calls the Mary Kay Image is essential to the development of a Mary Kay woman. As far as Mary Kay is concerned, traditional femininity and upright conduct are as important to beauty as plucked eyebrows and unchipped nails.

Dresses are mandatory for all Mary Kay functions and smoking is frowned upon. No alcohol is ever served at company gatherings because, according to Mary Kay, “alcohol and women just don’t mix.” Good grammar is encouraged, and profanity is taboo.

Besides these basic requirements, a Mary Kay woman’s lifestyle must be as pure as cold cream. The company is closed to anyone who is “openly controversial,” Rogers told me, explaining that, while a consultant can be terminated for bad behavior, she is usually forced out by peer pressure. As an example of how this natural law works, Rogers matter-of-factly cited the case of a former sales director whose husband was convicted of a felony. Word spread quickly, and, says Rogers, “she chose to resign because her husband had brought disgrace on the company.”

Conformity is the unspoken byword in Mary Kay. There is an almost boring sameness about the looks and conduct of Mary Kay women. At last year’s convention only 2 of 8000 women were there in pants, and both apologized personally to Mary Kay—one explaining she was new in the company and didn’t know about the dress code; the other confiding that she wore leg braces and thought pants more appropriate for her.

The company claims to take no political stands, but it obviously leans toward the conservative. In a speech opening the annual convention last summer, Rogers championed the free-enterprise system, drawing loud cheers for Proposition 13 and equally loud jeers for welfare. The company is officially neutral on the Equal Rights Amendment, but several years ago when there was a move in Austin to rescind ratification of the ERA, Mary Kay had to send out a notice that consultants and sales directors were forbidden to campaign for rescission as representatives of the company. Mary Kay maintains that the only emancipation the company espouses for women is economic liberation. “After all,” she says seriously, narrowing her eyes, “isn’t that what all the rest of it is about?”

One week each month, a new class of DIQs (Directors in Qualification) spends a week of intensive training in Dallas. By meeting certain quotas for sales and recruiting, 1 per cent of all Mary Kay consultants qualify to take these courses. They pay their own way to Dallas, and for many of them it is their first trip away from home alone. If, after her training in Dallas, the DIQ meets more quotas, she then advances to the level of sales director. This passage is marked by a “debut,” which usually takes place at a sales meeting and includes candlelight, formal dress, a bouquet of roses, a little oath, and happy tears.

Mary Kay insists on having personal contact with her women. Each week she personally signs hundreds of letters of congratulation, encouragement, condolence, and the like. She counsels them by phone and travels regularly to sales meetings around the country. She also conducts a DIQ class one Wednesday each month, and I sat in with a group recently.

At 9 a.m. on this particular DIQ Wednesday, the class was waiting excitedly in the auditorium of the corporate offices. They reminded me of nothing so much as a sorority pledge class, breathless and with a doe-eyed kind of innocence.

Mary Kay entered, wearing a purple Ultra Suede suit, and on seeing her the DIQs jumped around squealing and clapping, welcoming her with the Mary Kay enthusiasm song, which is set to the tune of an old Sunday school hymn:

I’ve got that Mary Kay enthusiasm

Up in my head,

Down in my heart,

Down in my feet,

I’ve got that Mary Kay enthusiasm

All over me,

All over me to stay-ay-ay!

For four hours, Mary Kay Ash dispensed to 24 adoring DIQs various tips on how to book Beauty Shows, how to avoid having to deliver products to customers, and how to get their units organized. “If there’s any one problem common to most women in this company,” said Mary Kay, “it is the inability to get organized. It isn’t that we’re less intelligent, it’s that we as women have to juggle so many balls at once.” Mary Kay’s suggestion that each DIQ hire a housekeeper may have come as a mild shock to them, but she explained to the group, “If you’re smart enough to be here, you’re wasting your time scrubbing the floor,” to which the class responded with applause.

The group remained spellbound all morning. Mary Kay manages to be a kind of untouchable ideal to her sales force and at the same time one of them. During the session, she complained genuinely to them about the price of tube tops at Neiman’s, traded recipes, and suggested that they Scotchgard their director’s uniforms to save on dry cleaning. Like all other DIQ Wednesday mornings, this one ended with Mary Kay softly extolling the golden rule as if it were the company’s exclusive property. As her last gesture, she made her way from desk to desk, handing each DIQ a miniature globe with the golden rule inscribed around the equator. “Keep this in your purse all the time,” she advised, “and when you have a question you can’t answer pull it out. Think of the golden rule and you’ll always have the right answer.” Each blue plastic marble was accompanied by a squeeze of the hand and a benediction from Mary Kay. By now most of the DIQs were either clicking their Polaroids or totally dissolved in tears.

This wouldn’t be the DIQs’ last encounter with Mary Kay. Later in the afternoon they would attend the traditional DIQ tea in her home. But first there was lunch in the Trellis Room of the Mary Kay manufacturing plant just down Regal Row from corporate headquarters, followed by a tour. Two manufacturing executives, one wearing a crisp white lab coat, met the DIQs in the lobby of the plant. They divided the two dozen women into two groups, and the one I joined stopped first in the office of Joseph Karolyi, a member of Mary Kay’s research and development department. Karolyi, whose title is Consultant in Medical Affairs, has been with the company eight years. Before that he worked for Clairol and Max Factor. Seating the DIQs on couches, he offered to answer any questions about the cosmetics.

The first question was touchy. “Uh, the hormonal change women go through, you know. Can that make the skin oily?” Karolyi answered this and the other questions frankly, although he made the DIQs noticeably uncomfortable by using such terms as “menopause,” “ovaries,” “period,” and “zits.”

“How can I justify selling night cream to a teenager?” asked another DIQ. Get her the special formula, advised Karolyi, and emphasize use of the mask and skin freshener. “As a matter of fact,” he added, “some people should probably just stay with the glamour items.”

“And not use skin care?” shot back an incredulous young matron from Louisville.

“You’re pinning me down!” Karolyi complained. And on this nervous note we were quickly dispatched to the actual manufacturing facility, a great expanse of stainless-steel vats and color-coded conduits.

Back in the lobby, I took a quick poll of the twelve ladies. Eleven were married, eleven had children; the one unmarried DIQ looked miserably embarrassed about being different. All of them said their Mary Kay careers were not their primary means of support. Five went to college, two were in a sorority. One woman showed support for the ERA, five said they opposed it, the rest registered no opinion.

At 4:30, the DIQs arrived at Mary Kay’s white stone home set tranquilly by a lake and among trees near NorthPark shopping center. Mel Ash, Mary Kay’s husband, welcomed the group. “I think I’ve died and gone to heaven,” swooned a young woman from Toronto as she surveyed the gilt and brocade of Mary Kay’s living room. It had been a long day for the group and they all kicked off their shoes and buried their toes in the thick yellow nylon rug.

Mel and Mary Kay were married in 1966, and when I asked him to tell us about their courtship, all the DIQs were rapt. The first time he saw her was on a blind date. She met him at the door in a black dress. “Mary was gorgeous,” he said, sighing, “and I know you won’t believe this, but there was a light shining in the background, and, well, I saw a halo around her. Of course, I knew then she was the one for me.” Mel always helps Mary Kay greet the DIQs, and together they have worked out a little routine. She takes one half of the group, he takes the other, and they start in different directions in a tour around the house. Apparently the DIQs had heard about the house from their friends, because they all knew what to look for. The highlight was the sunken marble bathtub in Mary Kay’s pink boudoir. Each DIQ who had a camera posed in the bathtub while another DIQ snapped her picture.

Mary Kay and Mel Ash live a quiet life at home. A typical evening is spent in the den, which is walled with Reader’s Digest condensations. Mel usually watches television while Mary Kay attends to her correspondence. Mel Ash is a romantic husband. He has given Mary Kay a gift each Thursday since the Thursday they got married. “After sixteen years,” he admits, “finding new baubles is about to drive me crazy!”

As the sun began to set, the DIQs drank spice tea and ate Mary Kay’s homemade cookies in the atrium in the center of the house. Mary Kay had changed into a black caftan for the afternoon and, as the chatter subsided, she took a central position on the green indoor-outdoor carpet to field the last questions from the group. One DIQ brought up the subject of recruiting men, and Mary Kay advised against it. The only successful male in the company is Arnold Peden, who works in Canada. (At last year’s convention he wound up in the Queen’s Court of Personal Recruits.) “Frankly,” Mary Kay said, “recruiting men is a waste of time. This company is for women, and I’m proud of it. I’m convinced that when God made man he was just practicing.” Mel offered some parting words of inspiration, and at 6:30 two dozen starry-eyed American housewives floated back to the Marriott Hotel.

At the end of a Mary Kay year lies Seminar. Eight thousand consultants and directors pay their way to the company’s annual convention for three days of instruction and three nights of dreamy splendor. It is climaxed by Awards Night, which is part Miss America pageant, part TV game show. Until this year. Seminar was held in August. Seminar 1979 will take place this month, and next year it will move permanently to January to perk up post-holiday business.

Seminar is always a gaudy extravaganza. Last year’s bill was about $1 million, including the cost of gifts for the year’s best performers and regalia like capes and rhinestone tiaras. A huge, sanctuarylike lobby is usually set up at the entrance of the Dallas Convention Center. Oversized oil portraits of the national directors are hung there, flanked by a pink Cadillac and cases displaying the other awards. Throughout Seminar, women flock to this area to take off their shoes and walk around on the plush red carpet and have their pictures taken beside the Cadillac. Nearby is a special display of photographs mounted on glittery red valentines honoring the twelve sales directors who were dubbed Miss Go-Give Spirit during the preceding year.

The most conspicuous Seminar expense is the original set created for the center arena by Dallas designer Peter Wolf. In 1976 the set was a giant birthday cake. Last year, at a cost of $66,000, the stage blazed with a giant light show. It also featured a Busby Berkeley set of hydraulic stairs from which the glowing national directors would ascend like Venus from the foam.

Company executives emphasize that Seminar is not all razzle-dazzle. Classes are held in which successful directors give tips on selling Mary Kay. “Nod your head yes when you’re talking to your customers,” suggested one instructor in a class on sales techniques. “It’s a mild form of hypnosis. And look them in the right eye because the right eye controls.” Other Mary Kay injunctions: phrase your questions to get a positive answer; touch a customer often to show her you care; when it is time for the sale, give the customer the complete set to hold, because if she’ll hold it she’ll buy it.

For additional positive reinforcement, the national directors take the podium to tell of their own successes—usually thanking Mary Kay, God, and their husbands, in that order. Nancy Tietjen reported last year that before joining Mary Kay she was working on the assembly line of a munitions plant: “I wasn’t getting a bang out of it. Now, I walk out the door every morning and say, ‘Hello, America,’ and go to bed at night and say, ‘Thank you, Mary Kay.’ ” Virginia Robirds, who before her Mary Kay career didn’t wear makeup and wasn’t allowed to go out at night, now claims that her son wants to grow up to be “just like his mother!”

All Mary Kay achievers live and work for Awards Night. It is then that the top performers receive prizes for sales and recruiting—tiaras, banners, cloaks, flowers, and Cadillac keys. The five queens are crowned and they and their courts (the runners-up) promenade down a runway to the accompaniment of a show band. Meanwhile, the desired result is accomplished in the audience. The less motivated rededicate themselves for the months ahead so they can be onstage next year.

In 1976 I spoke with a young woman about Ruell Cone, that year’s top director, who ended Seminar dripping with diamonds and ribbons. “What meant the most to me,” the woman told me, “was when they handed the microphone to Ruell’s husband and he said, ‘I think she is so wonderful!’ That was more important to me than her prizes. This is one of the few companies where you can go as far as you want and be yourself, without sacrificing that other part, the family part.”

The rise to Queen’s Court is rarely easy, and for many thousands of Mary Kay women the gap between wish and fulfillment remains just that. But there are other thousands who do respond, who undergo a visible transformation. For them Mary Kay is a charm school, summer camp, and sorority, all rolled into one—a truly American female enclave where competition is cushioned by sisterhood and support. In some ways the woman entering Mary Kay is an uninitiated child. If she makes it in the company, she becomes a woman for life.

Coming of age—coming into one’s own—is a goal shared both by the feminists, who have changed our lives radically over the last decade, and by the women of Mary Kay. Because I came of age in a time of social ferment, I am different from women like Mary Kay Ash and Ouida Caldwell. But I am like them as well. I grew up with similar expectations regarding the most important things in a woman’s life. I also value the need for family, or at least a sense of it. And I imagine that Mary Kay’s women and I share hopelessly romantic sentiments. I too want to be beautiful, not just for myself but for the man I love.

I confess: I bought the works from Ouida. Almost every woman approaching thirty starts casting about for a little help. Ouida and I may have a long association after all.

Carol Edgar edits Vision magazine for KERA-TV in Dallas.

- More About:

- Style & Design

- Business

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Dallas