This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

You’ll be reminded in this final segment that Texas is too big for generalizations. One man’s wilderness is another’s playground, and avarice recognizes no sovereign. What makes perfect sense in the damp forests of East Texas is frequently absurd viewed against the backdrop of the Davis Mountains. You don’t herd cattle the same way in Presidio as you do in Alpine, a young woman tells us. An ancient buffalo wallow near what was once a sea of grass reminds us of a vanished time, and an heiress points out that our upbringings can be as various as our terrain. The young son of a Hill Country doctor goes to bed with a John Deere catalog, and a day care administrator in West Texas notices the dwindling truck traffic on I-20 and wonders if things will ever be the way they used to be. Nothing stays the same—we know that—but the yearning for our larger-than-life heritage is irresistible and the images of half-focused memories can be more real than truth itself.

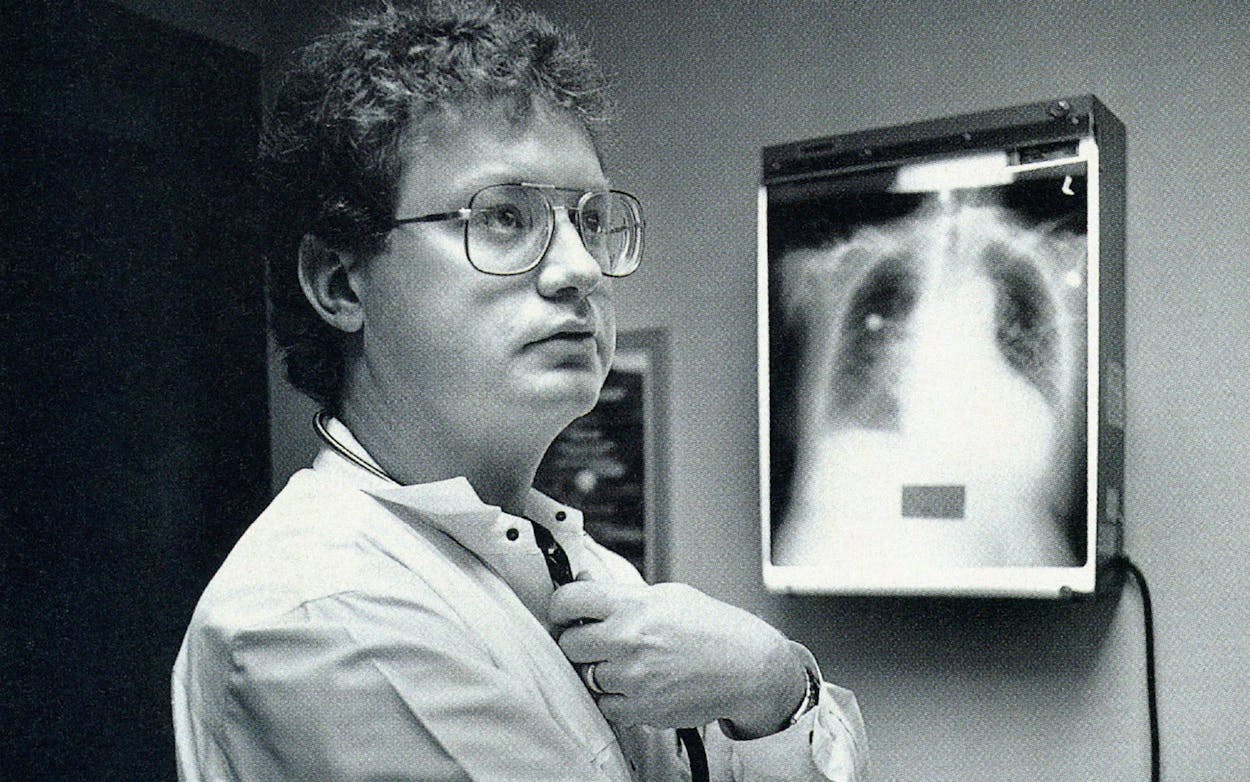

Leo Tynan

Doctor

Fredericksburg

Raised in San Antonio, Leo Tynan decided when he finished his residency that he wanted to practice medicine in a small town. In August 1988 he accepted a position with a clinic in Fredericksburg. With his wife, Elizabeth, and their two small children, Tynan lives a pastoral existence in a spacious two-story farmhouse with a tin roof. The 33-year-old physician is the picture of the young professional on his day off—jeans, loafers without socks, reddish-blond hair trimmed short, gold-rimmed glasses, a tumbler of iced tea in his hand. Seated in front of a huge fireplace, Tynan talks about life as a country doctor in a German community.

The medical history of Fredericksburg is fascinating. Some of the great old doctors here were Dr. Keyser and Dr. Keidel, and back in the thirties and forties those doctors did everything. There are still a couple of old clinics where the upstairs is an operating suite. They’d just throw the windows open and get started.

Then about eight years ago Jack Swanzy came here as the first internist, and he started taking care of the more complex problems. Prior to that, if anyone required specialized care, they’d send them off to San Antonio. They are very provincial here, you know: The worst thing that can happen to somebody who is sick and who has been here all of their life is to be shipped off to San Antonio. Being the only internist in town, Jack Swanzy was never able to get away. In a small town, if you take a day off, they’ll just call you right at home, they’ll drive to your place, they’ll even send the cops after you if they can’t find you. Jack was finally at the end of his rope, and he wrote a letter saying he’d be interested in having another internist, and that’s how I happened to come here.

I had been to Fredericksburg with my German grandmother to pick peaches and had always thought it was a nice place. My grandmother’s family came from Germany in the 1840’s, during the time of the mass migration, and settled around what is now Canyon Lake, around Cranes Mill and Startzville. She was third generation, but, of course, her first language was still German, and she remembered all-day trips to Fredericksburg. It was only forty miles, but back then travel was so slow that a distance of forty miles meant that the names and the people were very different from the names and people in her neck of the woods. She remembers laughing at how funny the German spoken in Fredericksburg sounded, compared to Startzville.

People here live to be 95 years old without blinking an eye, and they’re active until the end. There’s not a lot of drug or alcohol abuse like you see in San Antonio, but here you deal a lot with the natural history of aging. Sometimes you’ll be called on to treat a ninety-year-old who has never been to a doctor, so you’re coming in at the tail end of things. There’s not a lot technology can do. We can sometimes pull these old folks out of the fire by being very aggressive, but a lot of times they don’t want that and their families don’t want it. When people are in their nineties and are ready to die, you have to go with it. That was something I had to get used to.

There’s a small vocational nursing school that has been here for years and trains hometown girls to become nurses. Some of them go on to San Antonio and train to become registered nurses, but most of them become licensed vocational nurses here and go into the hospital and work. And so there’s often an emotional tie already present between nurse and patient; they’re taking care of people who are their grandparents or their uncles and who baby-sat them when they were little girls. Boy, does it make a difference! Patients feel like they are surrounded by family and friends. I remember one night this man in his forties who had been healthy up until that day had a terrible heart attack and died twice in intensive care, and after hours we finally got him stabilized. And as we were wheeling him out of the unit, a nurse who had known him since he was a little boy kissed him on the head and told him, “We love you.” You don’t see that in a big hospital very often. But you cry a lot easier here too. Especially when someone whose time hasn’t really come yet comes in real sick or badly injured in a car wreck, and the shock wave spreads all over the hospital. That’s when it gets hard.

The German language is still very strong here. In my family, my mother still speaks German, but the language was mostly lost on her generation. But in this town people my age still speak German. Lots of the nurses speak German. I’ve taken care of very sick elderly people who are not responding, and then one of the young nurses will speak to them in German, and they’ll wake up and respond and talk to them.

Fredericksburg has an interesting social fabric. It is fairly evenly split, as I understand it, between Catholics and Lutherans, and there’s always plenty of dissension and bickering about things. But basically, it’s a very unified town in the sense that there’s always work to be done, things that need improving. You just don’t see idleness here. It’s not a wealthy town—there’s very little opulence—but people work hard and are satisfied to work hard. Fredericksburg has a fairly forgiving attitude about people who can’t work but not for people who won’t work. And they look pretty closely at people to tell the difference.

Then there’s that group of people who’ve been here forever. They make up a very large part of the community. A lot of young people leave, but at some point many of them seem to come back. People tend to stay on the farm or work the ranches that they’ve worked for years. The house that Liz and I lease is surrounded by a nine-hundred-acre dairy farm that has been in the Hagel family for a number of years; in fact, there are three generations of Hagels still working that farm. Our son, Matthew, goes over and rides the tractor when they are plowing.

Matthew and his little sister, Eileen, are experiencing a childhood a bit different than what they would have if we’d stayed in San Antonio. Matthew is four and—it’s just hysterical—he goes to bed with John Deere catalogs and training manuals. His big deal now is looking at different types of manure spreaders and silage wagons. Liz and I realize, having grown up in the city, that there are a lot of things we left behind that kids need in terms of exposure to life. But then there is also a lot out there that I’m glad they’re not going to be exposed to.

Linda Walker

Rancher

Lajitas

Walker’s grandparents were pioneer settlers in the Big Bend country. Linda, who is divorced, operates her grandfather’s ranch near Presidio and the stables at the Lajitas resort. Sitting in her office in front of the stables, Walker, 33, talks about her strong feelings for the family ranch and the hardscrabble difficulties of ranching on the border.

My grandfather came out here from Menard County in 1910 and recognized the potential. He bought three or four sections and built a rock house at the head of Mariscal Canyon—what is called the Old Tally Place. Then when World War I broke out, my grandfather and two of his brothers essentially dodged the draft by staying across the river in Mexico. After the war they went to San Angelo and got right with the U.S. government and were in and out of the Big Bend for years. In 1949 Grandfather bought a ranch up the river from Presidio that’s still in our family.

I was born in Colorado and grew up traveling back and forth from Colorado to the Big Bend. My grandparents had moved back down here when Grandfather was 86 to live on the ranch by themselves, with much objection from all of us. But it turned out to be a wise move, and they were very, very happy. I had a guide-and-outfitting business in the summer in Colorado and also worked as a veterinary technician, but I decided that I was losing something important to me and that my time to do something about it was limited. So seven years ago I started coming down and helping them with the ranch in the winter and living with them there. My grandfather was 93 when he passed away in 1987. I learned so much from him.

The Walker Ranch is about 22 miles upriver from Presidio, toward Ruidosa. We own about a section and run on about eight sections. You talk about a West Texas ranch—it’s nothing, just an old adobe house built on the river—but I partly grew up there and it’s important to me. No one is making any money, we’re just managing to pay the man who works for us. He’s from Mexico and has been with us for ten years and lives there with his family.

Cowboying and running cattle down here is a world of difference from the operations up around Alpine and Marfa. Cattle here are real wild: a good cowboy handles ’em quiet and easy. We don’t rope ’em, because when you run at ’em with a horse two or three times, you can’t get within a mile of ’em again. I mean, you’ll ride up a hill half a mile away, and they’ll scatter like a covey of quail. Once they get down into the thickets, they’ll hide behind a bush like a deer and watch you ride by, and you’ll never get ’em out. So we catch ’em and trap ’em at water or feeding places, mostly.

You learn to outthink cattle. It’s what you have to do. I had an old ranch hand tell me, “Hell, your grandfather knew what those cows were going to do before they did.” Those pictures of cowboys right next to the herd whooping and hollering and stuff—that doesn’t happen down here. You just kind of keep them in sight and anticipate where they’re trying to go.

There is a saying down here that if you ever drink the water of the Rio Grande, you’ll never leave. Maybe that’s what happened to all of us in Terlingua and Lajitas. This has always been a land of outlaws, of people who drop out or choose not to be involved in the race that the rest of humanity is running. My grandfather was one of those people, absolutely. That’s why he went back to the ranch in his old age.

Elroy Brown

Farmer

Webberville

Brown, 56, has farmed all of his life, raising his family in a hundred-year-old shack in eastern Travis County. His children are grown now, but Brown continues to work the land, supplementing his income by plowing (often with a mule), planting, and cultivating crops at the Jourdan-Bachman Pioneer Farm, a living museum where visitors can observe firsthand the ways of a vanishing agrarian society. Seated in the living room of the mobile home where he and his wife have lived for the past three years, Brown reflects on the hardships of farm life and its simple eloquence.

Me and my twin brother were born right over here on the Blue Goose Road, off of Highway 290. A black lady named us Leroy and Elroy—Leroy is ten minutes older than I am. Why a black lady named us I just don’t know. When we were kids, me and my brother, we’d go to the field and chop barefooted. We’d stop and kill a rattlesnake and keep on chopping. I tell the kids up there at the Pioneer Farm, “I’s eighteen years old before I knew what a pair of shoes were.” Not quite that bad, but nearly.

I quit school to help pick cotton and make a livin’. The older generation, like my daddy and some of them, they worked harder than we did. It got where a man could work and support his family. But now things has got so high that everybody’s got to work again—I’m talking about kids—to make a livin’. And they going on about drugs being our number one problem! It’s making a living’s our number one problem. I mean, that ’fects everybody.

Everybody oughta have to farm, to know what farming’s like. I’m out there in the field at the Pioneer Farm, chopping cotton or corn and wringing wet with sweat. And the staff are going through with a tour group of kids, and I’m laughing at ’em under my skin, saying, “Y’all don’t know what work is!”

Sometimes I stop and ask the kids, “Does a horse and a cow get up the same way?” They don’t know. And I say, “No, the horse gets up the front end first, and a cow gets up from the back end.”

Until our kids got growed and we moved to this house in 1987, I never lived in a house that had a bathroom. We had an outside toilet. We didn’t have no hot water heater. We heated water and took a bath in a Number Three tub. It would get so cold in that house, we’d be eating supper and we’d have to run over to the stove and warm up and then run back and eat a little. And now I wake up in a different world. I love the bath and the shower.

That old house—one time we were watching TV and a big chicken snake went to crawlin’ across the VCR. Another time a skunk got loose and was hiding behind the stove, and I kept trying to hit him with a broom.

And when he stuck his little head out about the fourth time, I popped him right up side the head. When I hit him, he let out that spray. Well, I wrapped him in some newspaper and took him outside and buried him in that sand—it’s black dirt here, but sand up there—and took some Lysol and stuff and tried to kill that odor.

My kids wouldn’t invite none of their school friends to come eat or stay the night with them ’cause we was ashamed of the house we was living in. It was a shack! And Brother Smith, our pastor, we did ask him to come and eat dinner with us a few times, but, you know, he understood what the problem was.

It was just an old house. But we’s happy, and I thank my wife, Viola, for staying with me and putting up with all that. But we stayed in there and raised two kids. Carl was 17 or 18 when we moved from there—now he’s 20. Susie is 22. She’s in the Air Force, a radiology technician, and she wants to get a doctor’s degree or a nursing degree. My mama has that Alzheimer’s—I call it Old Timer’s—disease, and she don’t really know what’s going on. She don’t even know you when you go in to see her. She used to make the best chicken-egg noodles you ever put in your mouth. And you know, nobody got the recipe before she lost her mind.

Bobby Calhoun

Logging Contractor

Kennard

Calhoun, 48, has lived in the Davy Crockett National Forest all his life and notes with some sadness that things do not remain the same. The crack problem is so bad, for example, that for the first time in memory Calhoun is forced to lock his front door. From the front porch of his frame house Calhoun enjoys the sweet smell of wood burning at a nearby mill. A handsome, soft-spoken man with a slow smile that broadens to reveal a gold-edged tooth, Calhoun talks about his battle with the environmentalists and about a changing way of life in the Piney Woods.

Our environment people, they’re giving us a lot of problems on this wilderness area. They’re saying that we’re destroying big resin pine that our grandchildren won’t even know anything about. They are designating so much area and calling it wilderness area and they want to keep us out of it. Don’t want us to manage it whatsoever. So I went to Washington in ’85 to hearings to testify what the forest means to me, living in the heart of the forest, and to try to stop them because this is the meaning of our life.

There’s no real good jobs around here and most of the people are on fixed income. The major plant is Oliver Bass’s sawmill and he works all he can work and that’s about the only means of getting money around here unless’n you’re cutting wood. So the wood has been a great inspiration to this community. It helps our school function. It helps me to get something to eat on my table. And I will do anything to try to stop them wilderness people from taking our land.

They’re trying to get more and more land in the wilderness area. I can show you where the bugs have come in and just destroyed acres and acres of it, and it just keep on strong. But they don’t want nobody to go in, they don’t even want no car or motorcycle or nothing. And I would sure like to show those people the wilderness area. There’s no activity in it; it just grows up wild.

People used to, when I was a boy, they used to raise cows and run cows in the woods, but now they have a law you don’t run your cows in a government wood unless you’ve leased it. So the woods are just growing up mighty wild and thick. Management makes a better forest. The people appreciate it when they come out from the city. They can walk in it, they can hunt in it, and if they happen to kill a deer they can get it out.

There is a problem here because the kids that finish school, there’s nothing here for them to do. So they have to leave if they want to have a little success. Like I say, the wood business is the only thing that’s really booming around here, and they’re messing with it so much that you really don’t want your kid to get off into it. So the only chance they have is to try to go to college and get away to find them a good job. There’s a lot of young kids that stays around ’cause maybe they can get a job in Lufkin and they travel back and forth. Then some of them get a job in Crockett. But as far as living here in Kennard, there’s nothing that would attract them here.

Basically I got into this business because my father started it. I tell everybody this, and i’m truthful about it in a way too: I stuck to something that would stick to me, and that was pine resin.

Kathleen Olsen

Land Heiress

Alpine

Olsen, 55, is the granddaughter of Alfred Gage, one of the great cattle barons of the Trans-Pecos. Gage died in 1928, leaving the ranch to his two daughters. When it was finally subdivided among eight grandchildren in 1950, Kathleen’s share amounted to about 62,500 acres. The K-Gage Ranch, as she named it, was spectacularly beautiful high country with rolling meadows of grama grass, sheer cliffs, and spiraling towers of red volcanic rock. All that remains today is 5,000 acres. A shy and reticent woman with a soft voice, Kathleen is now married to Paul Olsen, a printer at Sul Ross State. They live in a ranch house on the K-Gage, and she spends six days a week managing the Highland Inn Motel, which she owns.

My grandfather spent the money he would have spent going to Harvard and came out here from Vermont in 1883, I think. His older half brothers were already here, and together they formed the Gage Cattle Company, the first public cattle company in Texas. Then the brothers went back East. My grandfather was the only one who stayed, and he stayed until he died. When he died he owned half a million acres, stretching from Marathon to Alpine and then on to Marfa.

He died just before I was born, so I knew him just through stories and books my mother wrote. He had two daughters, Dorothy Gage, who was my mother, and Roxana Gage. Both grew up in San Antonio, were widowed in their thirties and remarried in their forties, and lived next door all of their lives. They ran their ranches all of their lives too. They inherited the country and ran it as a partnership.

It became a tradition for the family to spend the winters in San Antonio and the summers on the ranch; it was a tradition when I was growing up and it’s still a tradition. My grandfather built the Gage Hotel in Marathon and used it as his home away from home and his office, and my mother and my aunt built homes next door to each other in the Marathon country at Pena Blanca Springs.

In the fifties my mother and aunt divided the ranch in half so they could pass it on to the next generation. My aunt made her part into a corporation, a single unit that is now called the Paisano Cattle Company and is run by my cousin Joan Kelleher. Mother divided her share four times and gave each of us our part. So I got about 62,500 acres.

In the late sixties my husband—now my ex-husband—convinced me to let him sell all except 5,000 acres of my inheritance to build the Highland Inn and also a subdivision at the base of the mountain on the fringe of our ranch. Did I protest when he traded my birthright? No, I wasn’t raised that way. I was raised to let the man make the decisions. Let me put it this way: The motel and the subdivision wouldn’t have been my choice.

Except for my share, the rest of my grandfather’s ranch is still in the family and still being used to raise cattle. My son, James, is picking up the tradition. He leases the small part that I have left and is looking for more to lease. I feel very good about that.

Mike Levi

Cattle Breeder

Spicewood

Levi and bis father pioneered the Red Brangus breed on Paleface Ranch west of Austin, which Levi, 61, still operates. He is a lanky man with a weathered face and sharp features—he would have made a good Hollywood leading man in the forties. Seated in his ranch office amid a clutter of books, pamphlets, and unopened mail, Levi talks about his love of the land and the peculiarities of the cattle business. On the walls are pictures of buffalo that once roamed this prairie and Red Brangus. Married and divorced twice, Levi has only one heir, a stepson who is a partner in the cattle business.

My dad bought this ranch in 1938, when I was a youngster. He had been in the silk business, making silk yarn out of raw silk in Pennsylvania, but wanted to do something different. So he sold out to his family—they still own the business—and came to Texas. He just fell in love with Texas.

This is ranch country, good grass country. I’ll show you some old buffalo wallows before this day’s over. Old-timers around here tell me that seventy or seventy-five years ago you could get on top of one of these hills and see all the livestock on the ranch because there was no brush or trees at all, strictly grass. A combination of things happened. When the buffalo were ranging freely, they would come through in great herds, eat the grass down, and then leave. Then if they didn’t come back in time, the Indians would set the grass on fire and burn it. And that combination of alternate grazing and burning kept all the brush down and invigorated the grass. But fencing and stocking it permanently led to the encroachment of undesirable brush and species. The land never got time to rest. Every time a sprig of desirable grass would stick its head out of the ground, the livestock would eat it. We have a lot of what we call cedar—I think it’s really juniper. There was none of that, none at all seventy years ago. We have quite a bit of mesquite too, which came in during the drought of the fifties. So the nature of the country has changed and probably not for the best.

We’re in the purebred cattle business. Most of our young bulls are sold at auction in November, and buyers come from as far away as California and Florida. I’m proud of the Red Brangus. I get a lot of personal satisfaction seeing what has happened to an idea during a lifetime. Breeding cattle, you know, is not a very specific thing. There’s a lot of luck involved, millions of genetic combinations.

Funny how it happened. My dad had a nice herd of registered Hereford cattle in the late thirties—English breeds in those days were the dominant cattle in Texas, and crossbreeding was looked down on. That’s how my dad came to name the ranch Paleface, incidentally, after the white-face Hereford. Anyway, he kept Hereford in the front pasture, and they got all the care and attention, and in the back pasture were some Brahman crossbred cows with a Hereford-shorthorn-cross bull on them, really a mixed bag. But the calves in the front that got all the care weighed four hundred pounds and brought a nickel a pound, and the ones in the back pasture weighed five hundred pounds and brought a nickel a pound. He hadn’t been in the business long enough to be prejudiced against crossbred cattle, so that’s how he got interested in them.

After that he did a lot of very scientific crossbreeding, putting registered Brahman bulls on Angus, on Herefords, on shorthorns, on Charolais. He eventually came to the conclusion that the Brahman-Angus cross was the best. Most of those Brahman-Angus crosses were black, but some black Angus carry a red gene, and for years we raised black and red Brangus side by side. We tried for years to get the Black Brangus association to register the red ones, but they refused. So, along with eight other breeders, we started our own breed association. We felt real fortunate to have been in on the development of the breed from the word go.

Laura Shrader

Day Care Administrator

Abilene

Shrader, 36, is West Texas district manager for Kinder-Care, a nationwide day care service. Her husband is a newspaper advertising director, and they have a young son and daughter. Shrader grew up in Houston “back when it was a nice place to live,” but now she’s hooked on smaller cities and in particular on West Texas.

I like it out here. I like the wide-open spaces, but I also like being where I want to be—in town—in ten minutes. I don’t know; it’s just a good place to raise your family. I think if I was single, though, I probably would not stay here.

It’s got its share of troubles—especially the economy—maybe more than its share, but you just kind of keep on keeping on out here. A lot of people have had to leave, but I bet if they’re from West Texas in the first place, they’ll be back. A lot of people from other places aren’t always real happy out here, but I’m a convert. It’s probably crazy to be painting this rosy picture, but I guess you can say I’ve lived on both sides of the track, so to speak, growing up in Houston and now being out in the west.

West Texas doesn’t have the political clout in the state that obviously the other places do, but at the same time, I’m probably more politically aware out here and have met my representatives personally, whom I never really met when I was in the bigger cities. Out in West Texas the representatives come to where you are. And they have town meetings and things like that. Senator Gramm makes it out here a little more than Senator Bentsen. Charles Stenholm is our representative, and I’ve been hearing more about him lately because of all the different child care acts that are coming out—he’s been a part of them.

You can tell how the economy’s going by the amount of truck traffic on I-20. When I first took over at Kinder-Care, it was in the fall of ’85 and the truck population was great, lots and lots of trucks. Then when the bust hit, February of ’86, when it hit really bad, the truck population decreased, and it’s still not as great as it was. But it’s coming back.

Midland is an early warning system for the state of Texas. If you want to know how goes Texas, watch Midland. I think because our economy went first, nobody really paid a whole lot of attention. You know, the first bank to really bite the dust was in Midland—the tenth-largest privately owned bank in the United States. Then Houston starts moaning and groaning, and then it’s a big story.

But you know, it’s like West Texas is the eternal optimist, and maybe that’s what I like about it. Even when all the things are crashing down, it’s—well, we’ve been through this, it’ll be all right. You know we’ll come back.

- More About:

- TM Classics