This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Before the big fire last March, it would have been hard to find a more authentic cultural artifact of bygone Texas than Crider’s Hill Country dance hall. Located on the south fork of the Guadalupe River twenty miles west of Kerrville, Crider’s was a magnet in the middle of nowhere. Every summer Saturday night, starting around eight o’clock, a crowd of campers, locals, cowpokes, cedar choppers, summering city folk, and tourists migrated to Crider’s to see a rodeo, dance, drink beer, and eat burgers at family-size picnic tables. They paid a $5 cover charge for a kind of good clean fun as quaintly anachronistic as Crider’s itself.

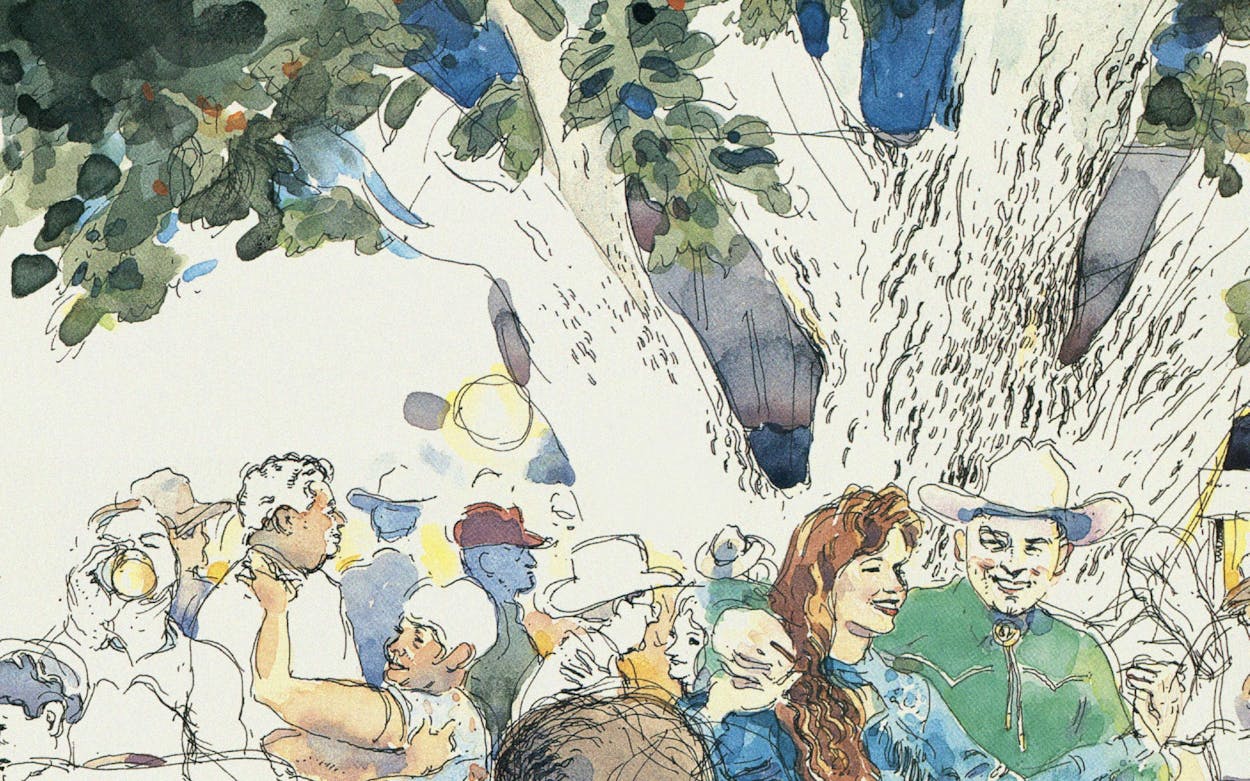

On those balmy, breezy evenings under halogen-bright stars, corny country and western bands twanged out tunes like Crider’s unofficial anthem, “Faded Love.” Toddlers frolicked at the dancers’ feet, and frosty-haired couples glided across the open-air concrete floor in forever-married sync. The place seemed as enchanted in its own way as the forest in A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

Crider’s opened in the mid-twenties, and the first dance floor, made of cypress planks, was down by the river. It stayed there until frequent flooding dictated a move to higher ground, across Texas Highway 39 next to Crider’s country store. In 1946 dancers moved to the present location on a bluff fifty feet above the original site. Over the years the dance hall became an eternal verity of sorts for my baby boom generation, and nothing about the place seemed more eternal than the enormous live oak that grew practically in the middle of the dance floor, surrounded by concrete. With a hundred-foot spread, the tree’s generous canopy shaded the adjacent cafe as well as half of the basketball court–size dance slab. But the thing that made the tree so special wasn’t its strength or size; it was its user-friendly accessibility. Five massive boughs sprang out like a fountain before sweeping down nearly parallel to the ground at head-bumping height, providing a natural jungle gym for kids, a courting ground for flirtatious teenagers, and a handy support for winded adults to lean against while having yet another beer before tackling the next Texas two-step.

The power of rejuvenation seemed to be among the tree’s many charms. Well into his eighties, Crider’s regular Harry Crate was famed for performing gymnastic feats using the tree and beer cans as props. If the tree made the old young again, it could also make the young older, or at least wiser. One twilit evening last summer, a bright-eyed two-year-old boy was playing horsey on a low-slung limb when he was smitten by a pixie in pink gingham. Leaning toward her, he gazed into her eyes with such unblinking intensity that she finally cried out for her mother. The tree had given them both a preview of yet another eternal verity.

Like the river below and the stars above, the welcoming oak seemed part of the public domain. We all had personal bonds to that tree, and the thousands who made Crider’s a summer Saturday night tradition assumed the oak would be part of Crider’s forever, for each successive generation to enjoy as much as we had.

We were wrong.

At one-thirty in the morning on an unseasonably cold and blustery March 15, Crider’s caught fire, its ancient walls burning as rapidly as seasoned firewood. In minutes the snapping power lines caused sparks to ricochet wildly from one part of the tree to another, as clumps of leaves flared up like Roman candles, lending a terrible beauty to their own immolation. The volunteer fire department was just four miles away, but by the time the firefighters were awakened and mobilized, the cafe was nearly gone, and half of Crider’s once-mighty oak had been scorched a sickening black.

Except in the local Kerrville paper, the demise of Crider’s did not make headlines. Like many others, I found out about it the hard way, when I drove past the cafe a few weeks later while visiting the Hill Country from San Antonio. I pulled into the parking lot, too stunned to keep driving. A nearby resident told me that for weeks after the fire, he saw other motorists sitting motionless in their cars and pickups, trying simultaneously to comprehend the devastation and pay their last respects.

I had been on my way to see friends at their weekend house, which they call the World’s End Ranch, but the scene at Crider’s fit that name far better. A mist fell as buzzards circled slowly overhead, and the silence was broken only by the sounds of the river rushing far below and the tires shushing on the rain-slick highway.

Finally I stepped out of my car to view the remains. The ramshackle wooden cafe and pool hall had been reduced to a rectangular heap of charcoal briquettes, bordered on that bleak day by an endless yellow ribbon cautioning: “Fire Line Do Not Cross Fire Line Do Not Cross Fire Line Do Not Cross.”

The tree looked half dead. The limbs facing the cafe were badly charred, but the other side was strangely unscathed, except that the once-supple green leaves were now brown and brittle. Scattered among the ruins were dented metal cabinets and a blackened ice machine. The only objects still intact were the concrete tubs that had once held iced-down beer and soda pop. Off to one side were several curled and twisted strips that looked like giant pieces of burnt bacon. I puzzled over them for many minutes before I realized they were all that remained of the building’s metal roof.

At first, everyone thought the blaze had been caused inadvertently, perhaps by someone who had taken refuge in the building that chilly night and built a small fire to keep warm. From the beginning, though, the Kerr County sheriff’s department investigated the fire as possible arson because the cafe was still closed for the winter and the electricity and gas were cut off. The department has found no evidence of arson, however. All the Crider family members have been asked to take lie detector tests; all have agreed, and so far those who have been tested have passed.

For weeks no one knew whether Crider’s would ever open again. Then the owners hauled off the charred lumber and set about putting up a makeshift building so that the summer season would not be lost. Crider’s cafe is once again open for business, partly new but hardly improved. In place of the old cafe, a plywood open-air concession stand dispenses beer and soda, sausages on a stick, and hot dogs—but the old menu of burgers, nachos, and fries is gone. And the magical oak that radiated strength shows unmistakable signs of decline. Two limbs of one major branch have been sawed off, and a low wooden fence has been erected around the tree’s multiple trunks to protect it and keep well-wishers at a distance.

The oak’s likely demise is hard to absorb. Like everything about Crider’s, the tree brought out the best in human nature, serving as common ground for the cross-section of humanity who coalesced, for the duration of those summer nights, into one big extended family. It made us more expansive, more serene, more benevolent. It bridged social and generational gaps, as everyone from oil tycoons to gas station attendants, from toddlers to octogenarians, rubbed elbows and linked arms, sliding on the cornmeal that substituted for sawdust, kicking up their Justin’d, Reebok’d, and Cole Haan’d heels. So pure at heart was Crider’s that when the sound system cranked out the chorus to the cotton-eyed Joe, everyone obeyed the owners’ prohibition against shouting the traditional refrain, “Bullshit!”

No one pretends we’ve lost a historical monument. Crider’s oak didn’t play a role in Texas history, as did Austin’s poor poisoned Treaty Oak. But it did figure in each patron’s personal history. In the case of my husband and me, it wielded a life-changing influence. After agonizing for years over whether to have a child, we watched one night at Crider’s as new parents held their babies in their arms and twirled under the oak’s sheltering boughs. Once we saw their radiant faces, we needed no other impetus.

Now my own child is three, and the dying oak has touched his life too. When he learned that he could no longer climb the tree and sit on its limbs, his eyes filled with tears. Tentatively, he reached up to touch the lowest bough. With its burlap wrappings, it looked like a wounded arm swathed in a gauze bandage. But why was there a fire, he kept asking, voicing the question we adults were too resigned and tempered by life to ask. Something that had once held him up had let him down.

The decline of Crider’s oak reminds us that nothing is immutable, nothing is safe. Before the fire, this serene slice of the Hill Country seemed removed from the darker forces of modern life. Not too many years ago this part of Texas was so secure that customers routinely let their sleepy children bed down, unwatched, in the back seats of their parked cars. No one would risk that today. As we grow into middle age and beyond, the ravaged oak seems to remind us how the world has changed, and we with it. Over and above our private reasons, we are mourning a collective loss of innocence and the optimism that goes along with it. We’ll miss Crider’s oak as long as we’ve known it—all our lives.

Kathy Lowry is a freelance writer who lives in San Antonio.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Hill Country