Loyd Powell could eat out at Mario’s every night and fun away at the Fairmont. But he doesn’t. Instead he’s usually on some sorry stretch between Big D and Inadale, picking chicken-fried from his teeth and sizing up the seismic implications of some old anticlines the big boys have overlooked.

For you boll weevils who don’t know the oil patch, an anticline is a fault in the lay of the land, an upfold of rocks which to the experienced eye might indicate oil or gas sands. Texas has more anticlines than any place this side of the Sahara, and while they’ve been picked over and produced for years, there’s plenty left if you’ve got the money and the time, not to mention the pipe and piss and vinegar, to lose your ass trying to bring one in. These days, you’ve got to be an independent son of a buccaneer to get away with it. You’ve also got to be lucky, science being what it isn’t. Loyd hasn’t always been lucky of late, it being the lot of the oil man to miss as well as hit.

Take this summer. One Saturday night in July, Loyd caught me at home and said, “Look, don’t get so drunk tonight you can’t get up in the morning.”

“Whatcha got going?”

“I’ll pick you up at four and we’ll hit ’em to Palo Pinto County. My pusher just called from the rig and said they’ll be hitting a little sand at 2200 feet and I’d like to take a look at it.”

Now I hate to get up early, but I felt I had no choice. I knew how important this well was to Loyd. It was his first in six months, and he had something like $60,000 in it. Okay, I said, I’ll break my date and see you in the morning. And that’s what I did. I called this beautiful blonde—her name is Erin and she’s my fourteen-year-old daughter—and said, sorry honey, can’t make it tonight. Can’t take you to Shakey’s for pasteboard and silent slapstick. I postponed again what was already a long overdue paroxysm of paternity. In Environmental America, old oilmen must stick together. It’s like the Masons. And my daddy was both, a driller and a secret riter. I dropped out of DeMolay but I couldn’t turn my back on memories of Longview, Gladewater, Kilgore, and Henderson. I went to bed early, with derricks dancing in my head.

Loyd, as usual, was on time.

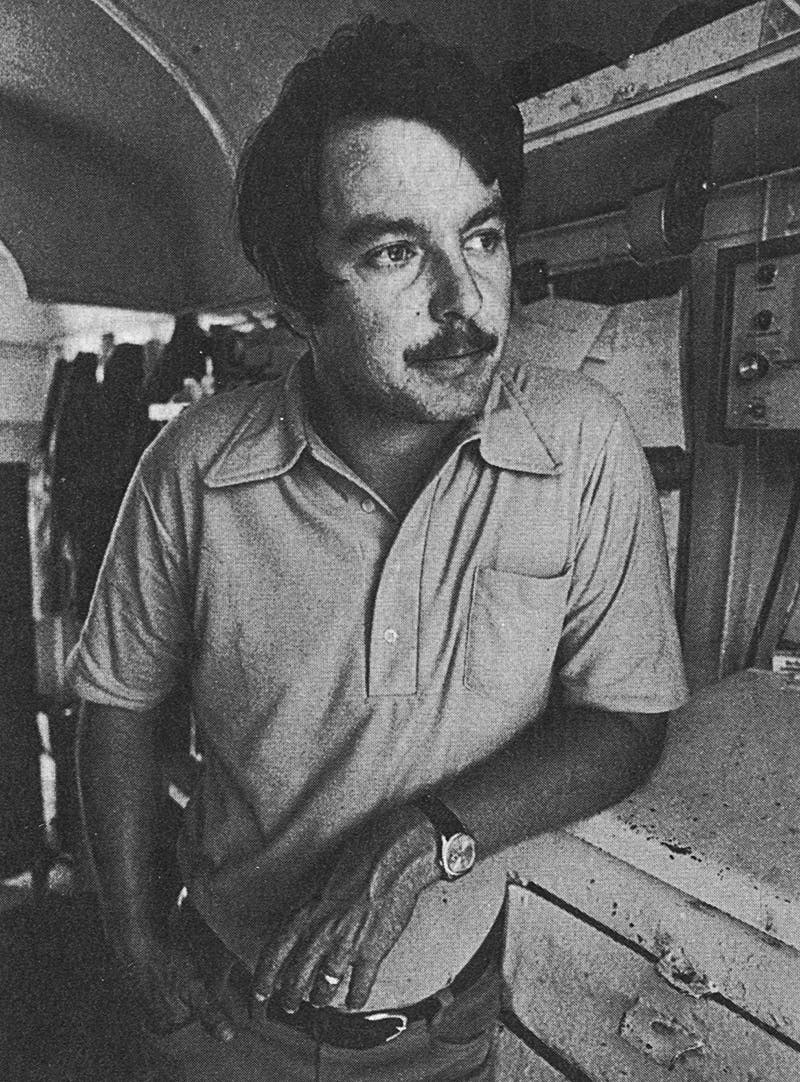

He had brought his damn dogs—Gretchen and Rex, two of the largest German Shepherds in captivity. Celeste, Loyd’s young bride, was away for the weekend, visiting her folks in San Antonio, and Loyd had orders not to leave the puppy-poohs alone, Gretchen would fast in protest, but the dogs reigned from the back seat of the Cadillac. This bothered me because I had invited Gary Bishop along to take photographs, and I knew that Gary would be grumpy at such an hour, and grumpier still at having to compress his loose and elongated frame into the leftover space next to two German Shepherds. But Bishop is a pro and didn’t bitch. He said later he was afraid the dogs would bite him.

To the West we rolled, out into the July dawn, through four counties and into the rural ennui of abandoned barns and absentee landlords. A Cadillac, even with giant police dogs breathing down your neck, is a compelling conveyance. Quiet, sleek, heavy with power and luxury, it soothes fears of the open road and of strange companions, and Loyd and Gary began to feel one another out. Both are about as timid of talking as Twain on the Chautauqua, but since they are quite opposite characters, their separate loquacities took some time to tune up.

Loyd is an anachronism. In his manner and dress, in his ideas and values, he is a swashbuckler of the Texas Fifties. He looks like he just stepped off a Trans-Texas prop plane from Austin, where he has been closeted at the capitol with Governor Shivers and Price Daniel (the old man, not the boy), plotting to keep the Texas tidelands and throw Harry Truman out of office. Gary, on the other hand, looks like a male model’s version of a chic Cosmo or Playboy photographer, all old denim and elegant equipment. Handsome and long-haired, he is in every way a man of the Seventies.

Loyd was the son of a rich roughneck, a scion of North Dallas, and Gary from the family of a middle class mechanic, a South Dallas success story, but already they had found common ground. Both had dated the same girl. Loyd had seen her first, back in high school, and he thought she had gone downhill since then, running around with hippies and such, while Gary obviously saw her as liberated at last from the strictures of life as a banker’s daughter. With the dogs at the back of our necks, and with that dichotomy of generations expressed in men of the same age at the back of our minds, we musketeered the morning away, skirmishing on sports, religion, and politics—Loyd lamenting Nixon’s plight and pointing out oil wells we passed, Gary grinning and shooting. We left Weatherford in our wake, passed through Mineral Wells, geared down in Graford, and took the Jacksboro highway out to the Jim Green place, where, on a hill behind the house, Loyd and the Carter Development Company had a double jack-knife rig boring away.

Loyd had had a helluva time getting the lease and clearing a road to the spot where he wanted to drill. It was like riding over a washboard. One of the trucks hauling in the works had turned over in a gully, and now, as we bumped along, we came upon a stalled car. A big, red-faced man in a dirty straw hat was inside the hood, banging on a battery.

“That’s my morning tower driller,” Loyd said.

Ray Mardis was his name, out of Ranger. His Chevy had been in the oil patch almost as many years as Mardis, and Loyd’s jumper cables wouldn’t rouse it. The rest of his crew had gone on in another car, so the driller rode with us to the rig and borrowed a truck to drive home.

The sun had already burned away the morning mist and the rig sat there silent, silhouetted in the cloudless sky. The bit had worn out so they had brought it out of the hole. The drill stem was

stacked in the derrick. The daylight driller, Ralph Ramsey, another old roughneck from Ranger, was in the doghouse looking at the electric log. His crew was off the floor, out in the parking area banging on the back of a second-hand Cadillac. Loyd put leashes on Gretchen and Rex and let them out of the back seat. “Let’s go to the powder room,” he coaxed, and they dragged him off into the mesquite.

Gary gazed in wonder at the rig. He had never seen one.

A wiry little man without a tooth in his head raised himself from the rear of the old Cadillac. “Say,” he said, “Let’s see if your key will fit my trunk.”

“What’s the problem?”

“Aw,” he said, grinning, “we locked ourselves out and cain’t get to the water jug in the trunk here. Just made a trip and ’bout to die of thirst.”

Loyd emerged from the mesquite and handed him the keys. They didn’t fit.

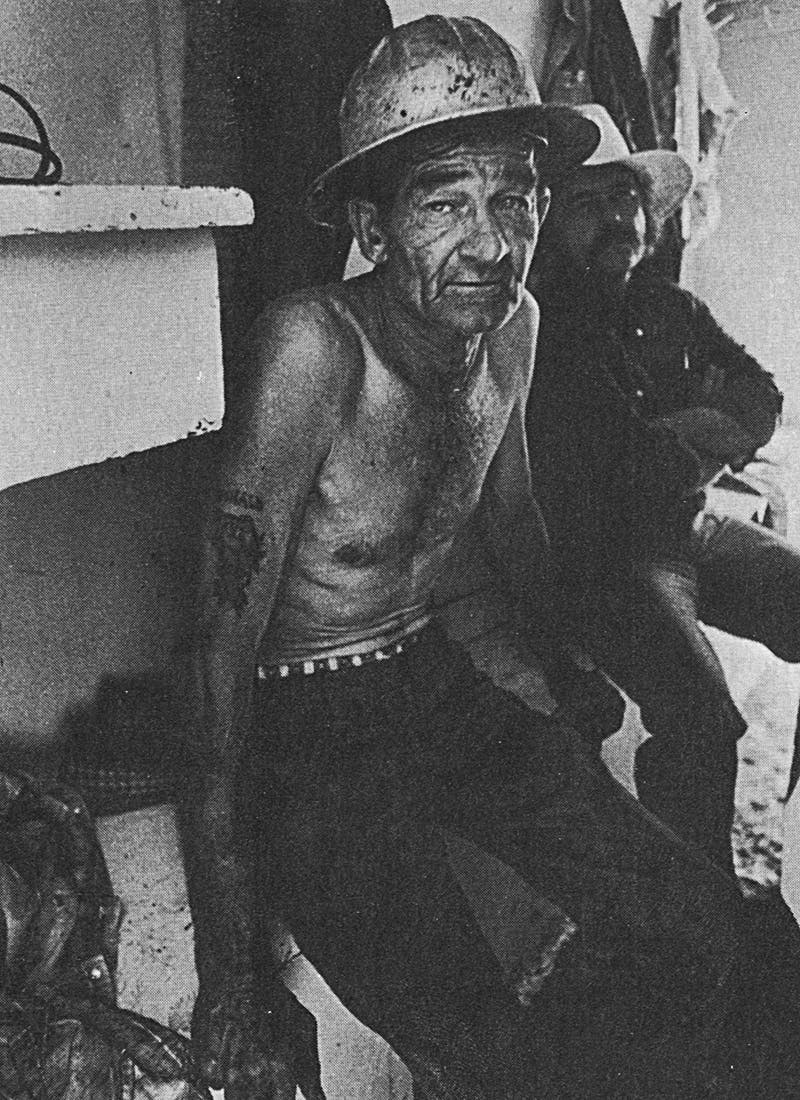

“Shit,” the little roughneck said. His name was Leroy Jacoby. He was the derrick hand. After 35 years in the oil patch he had two used Cadillacs and a girl in Borger, and here he couldn’t get a drink of water to save his soul.

Leroy shook his head and looked at the floor men, Chubby Smith and Derrell Teague. Chubby was a red giant, naked to the waist. He had broken in on his first rig back in ’49 at Hadacol Corner, between Midland and Odessa, surely the meanest stretch of honky tonks since Moonshine Hill. It was dead out there now, most of the big oil action gone. About all a man could do in the Permian Basin now was drink and fight and cuss every other word. Chubby had a busted disc, nine fingers, seven ex-wives, and seven kids. His eighth wife, Jo Ann, who had also been his seventh, was driving the twenty miles from Mineral Wells to the rig to give Chubby his high blood pressure pills. He’d gotten dizzy coming out of the hole and had called her on the shortwave.

“How’m I gonna down a pill without water?” Chubby said. He looked at Derrell. Derrell was the boll weevil, the inexperienced member of the crew, but he looked like he had been throwing pig iron around all his life. His biceps were so big they were bursting through his shirt. Derrell laughed and looked at me and I laughed and looked at Loyd and Loyd frowned and looked at the dogs. “I’ll tie ’em to a tree,” he said, “and we’ll go get you some water.”

We drove over to a post oak grove about a half mile away where the evening tower driller, Estel Martin, had his camp. Martin’s crew consisted of his son D. W., Estel’s brother Willard, and Willard’s boy, Willard, Jr. Some pickups and a camper and trailerhouse were arranged in a circle, like covered wagons in Indian territory, and when we drove up the women and kids scattered like chickens.

Estel Martin stood his ground. He was smaller than Leroy. “What do you want?” he said flatly. Loyd explained. Martin didn’t say anything. He just whirled and got a water can and handed it to Loyd. “We’ll need our own water tonight,” he said. “I’ll have ’em refill it,” Loyd assured him.

Gary was clicking away with his Nikon. Martin caught him out of the corner of his eye. “Hey,” he said, turning on Gary. “Better be careful with them pictures.”

“You don’t want your picture taken?”

“No,” Martin said. We tip-toed away.

Back at the rig, Loyd watered the men and the dogs and assayed the sand at 2200 feet. He looked at the Schlumberger log, sniffed the samples, talked to the driller, and talked to himself. “Porosity, porosity,” he said over and over. “It boils down to whether you’ve got porosity.”

He wasn’t going for oil; he smelled gas. He felt he was in the same structure as the Halsell No. 14, a good gas producer that had been drilled six years before. The Halsell was 4300 feet to the south. Of course to the north, 1900 feet away, was the Lillie Humphries No. 1, the wildcatter of the field which had been drilled fourteen years before and was a dry hole. You take your chances. Loyd had gotten as close to the producing well as he could. He told Ramsey to put on a new bit, a $1700 Howard Hughes sealed bearing special, and go on down to 2700 feet. Could be some development there. Slim chance, but worth a look.

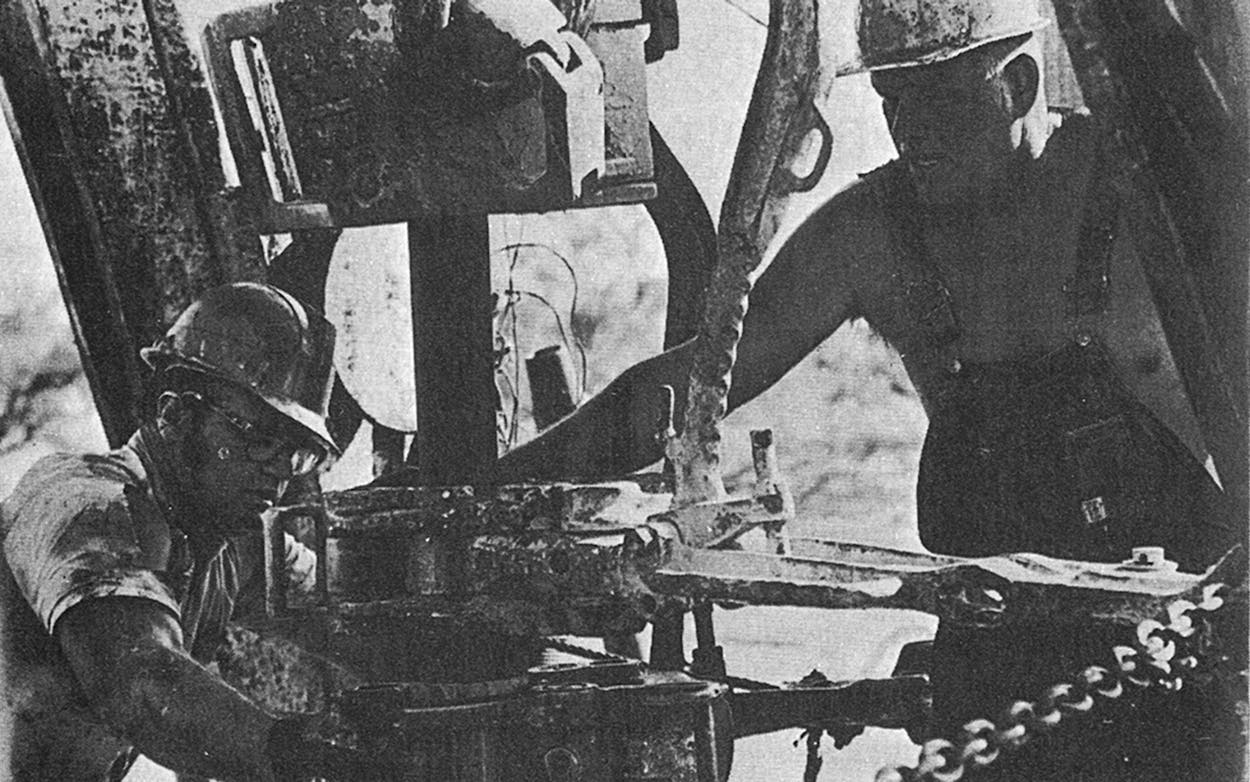

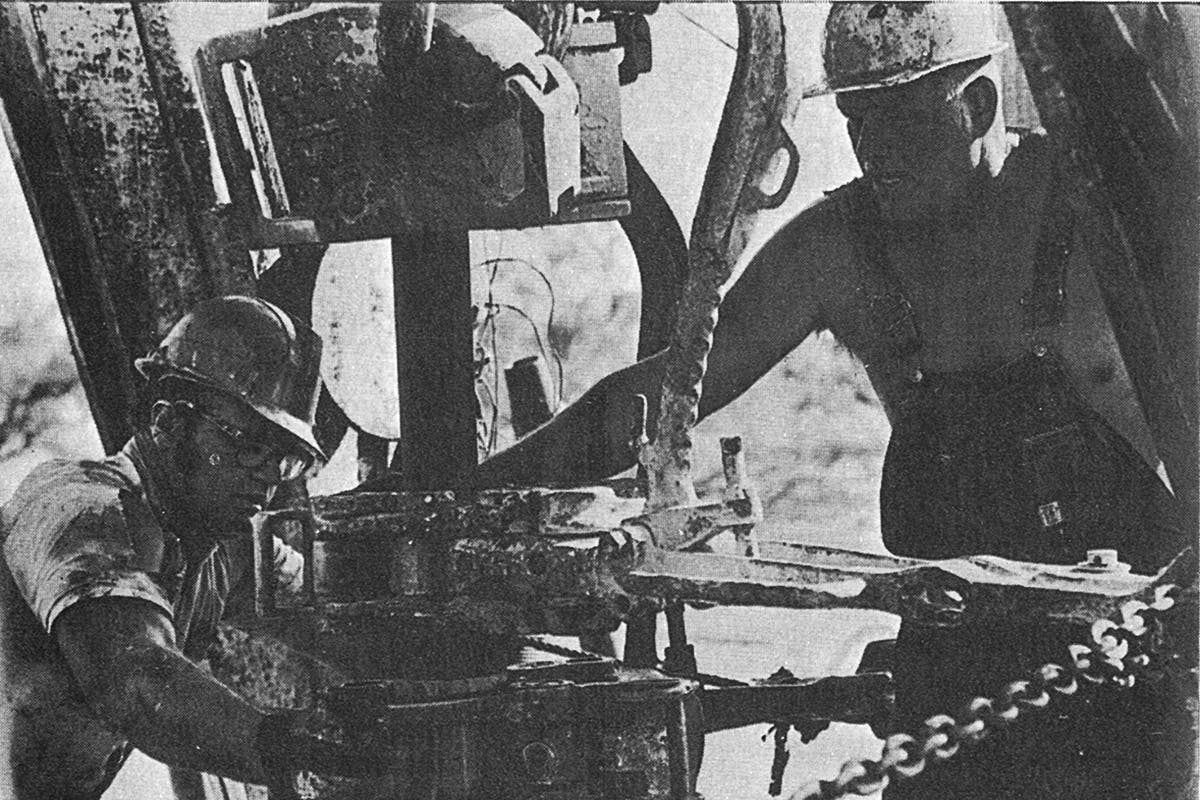

So they cranked her up, the Jim Green 1-A. Leroy went up in the derrick, Ralph Ramsey took control at the works, cat-head chain awhipping, and Chubby and Derrell stood over the hole and went at the pipe hammer-and-tong, stringing it together for the trip into the ground. The red Waukesha diesels roared, the rig groaned and shook, and the kelly joint went up and down, picking up pipe and putting it into the hole until they touched bottom. They took off the kelly and put it in the mouse hole. Ralph eased off on the bull wheel and let the bit on bottom rotate. Now they were drilling.

“Call me at 2700,” Loyd said, and we returned to Dallas. That was July 21st.

Within ten days, Loyd had bad news on two fronts. First John Connally, the best friend oilmen ever had in Washington, was indicted for taking a bribe. That was on the 29th. On the 31st, Loyd plugged the Jim Green 1-A at 4400 feet, gave it up as a dry hole.

At times in the past few years, Loyd Powell wondered if his inheritance was worth it, that maybe it was more curse than blessing. It was as if some ancient ancestor had sent anachronistic tendencies tailing off into the generations like time bombs, and Loyd was one of the wounded, a victim of genetic shrapnel. Yet he had only to look back one generation to see the source. For it was not the money and the responsibility to carry on that bothered him, but rather the predilection and passion of his father so apparent within him. He looked more like his mother than his father, but he was definitely the old man’s son. They both loved to squint into the sun. And that was the problem. It was one thing to be L. W. Powell, drilling contractor and independent oil operator in the boom days of East Texas, and quite another to be Loyd Walter Powell, Jr., second-generation oilman in Environmental America. Loyd was of this age all right, hell he was under 30, but he didn’t feel in it. He wanted action, not soul-searching psychology. Life was to conquer, not to contemplate, and Loyd’s head was full of stories of his father’s heyday.

It seemed a bolder, more adventurous time, more manly, somehow, than his own, and for a while there Loyd felt cramped at every turn of his growing maturity, a Gulliver in a land of Lilliputians. Going down to the office in the Exchange Bank Building just made it worse. He would sit there choking on his tie, with no place to go, and nothing that he really wanted to do. Here he was, an oily son of machinery and motion, stuck twelve stories high in downtown Dallas, hemmed in by paper money men and Ross Perot robots, when really his heart was out in East Texas on a drilling rig floor, spudding in and drilling, logging and notching, swabbing and coring and perforating, hitting a dry hole or bringing in a well, it didn’t matter—just goddam doing something!

Loyd wanted to do something the way they did in the old days. Sure it was dangerous, clamorous work that left them muddy and greasy and worn out after a twelve-hour tour, but God it was worth it. In every boll weevil and honky tonk waitress there was a wildcat streak that said you went out and got it while the getting was good. You didn’t worry about being laid off or hung over, that would take care of itself. Hell, wages were good and the oil sands stretched as far as a little financing and a good rock hound and Miss Lady Luck could take the bossman. A 40-hour work week and fringe benefits were scoffed at by drilling men. You paid a man for working, not for the time off and in between. Anywhere there was oil there was excitement.

Take a crossroads like Moonshine Hill, just outside Humble, Texas: 40 saloons and 20,000 roughnecks in tents. H. Henry Cline, who used to fire boilers, remembered walking down the mud-mired main street and counting six fist fights. W. H. Bennett, the old doctor at Humble, once said he made “right smart a-livin’” treating roughnecks for knife and gunshot wounds, not to mention the clap. Ross Sterling might have remained a feed store proprietor out there if oil hadn’t been struck. As it was, he ended up founding the mighty Humble Oil & Refining Company and becoming governor of Texas.

They refused to believe those boom days would end. Sure, fields dried up or ran out of drilling room; that was an axiom as old as Colonel Drake and Watson’s Flat. But if you couldn’t strike it anymore in Pennsylvania, you went to West Virginia, Ohio, Kentucky, California, Texas and Oklahoma! And so it went, through a hundred years and 32 states and 213 Texas counties, until something like 600,000 oil and gas wells had been brought in and tapped.

Loyd was the first to admit that they had been money-hungry adventurers, but hell, they were also trying to stay ahead of an insatiable and growing demand for petroleum products, not only in the United States but the world over. Every index in America was rising: there were more people, more jobs, more businesses, more houses and cars and trains and ships and planes. We came roaring out of World War I the most powerful and industrial nation on earth, and we went charging into the century’s new prosperity with the same gusto and abandon that had marked our exploration of the continent a hundred years before.

J. Frank Dobie, that deceptive cowboy of campus and chaparral, once summed up the oilman’s contribution to the American spirit. In the Old World, he said, the legends that persisted with the most vitality were legends of women—Venus, Helen of Troy, Dido, Guinevere, Joan of Arc. But in the New World, men have been neither lured nor restrained by women. It has been a world of men exploring unknown continents, subduing wildernesses and savage tribes, butchering buffalo, trailing millions of longhorn cattle wilder than buffalo, digging gold out of mountains, pumping oil out of the hot earth beneath the plains. Into this world, women have hardly entered except as realities; the idealizations, the legends, have been about great wealth to be found, the wealth of secret mines and hidden treasures, a wealth that is solid and has nothing to do with ephemeral beauty.

That was the way it had been, the way Loyd looked back on it. A saga. Restless, with raw appetites that grew in number as they were refined, we built industrial America! It excited him to think about it, there in his carpeted cubicle.

Loyd had come along a little too late. By 1955, the year he was nine and fell into one of his father’s mud pits, the oil industry of Texas and the Southwest was settling into pokey middle age. Most of the fabulous fields had just about been drilled up and the leases were left to workover crews and roustabouts, to the pumpers and switchers who tried to prime the last drop out of an old gusher. Nursemaids really. Out in most oil fields you couldn’t even get into a fight.

The real men, the explorers, had moved on to where the new play was developing, to Wyoming, to Alaska, to the Australian Outback and the Sahara Desert. And it was the kind of action that was too big and expensive for the independents, unless they gave up and went in with the majors like Humble. Not only was the easy oil in Texas harder to find, it was getting damned expensive to drill and produce. Costs of men and materials had gone up faster than crude oil prices. Of course, the industry had men in Austin and Washington to protect it—governors like Allan Shivers and John Connally, Speaker of the House Sam Rayburn, Senators Price Daniel and Robert S. Kerr of Oklahoma, even Lyndon Baines Johnson—but most of the special favors, federal tax relief and state limits on production, seemed to help the majors more than the little man. And it was the little man, the independent, who was doing most of the drilling and taking the losses on dry holes. And, damn, you got a dry hole about 38 per cent of the time.

Loyd’s daddy used to tell him that an oilman could go up quicker and come down faster than any other breed of man, and old L. W. was living proof. Out in East Texas and on the plains he and Red Iron had gone in together on a shoestring with another fella and before they knew it they were worth a half million. Then Red fooled around and lost it on some wells in Mississippi, and suddenly they were broke. “Red,” L. W. said, “I know you’re in bad shape, so I’m gonna give you my stock and start over.”

They shook hands on it, but before they parted, Red, with understandable embarrassment, told L.W. that he had to have $500 to pay his grocery bill. L. W. went to the Gladewater bank and borrowed the money, telling Red to pay him back when he struck it rich again. They found Red dead one morning not long after. He’d had a heart attack while reading the Dallas Morning News. The Japanese had attacked Pearl Harbor and President Roosevelt was declaring war. L. W. was 41, but he enlisted.

When he got out he married a Nacogdoches school teacher, Reba Jo, and went back to drilling on contract. After a time, L. W. got a stake and started operating as an independent. He knew the technical side of the business—by this time he had drilled more than 2000 wells—so he bought his own portable rigs and ran them, and as the wells were brought in and producing, L. W. kept a crew of roustabouts to look after them and the tanks. He set up headquarters in the Exchange Bank Building in Dallas, hired Robert Bozman as his accountant, and stationed his field superintendent, Arnold Rohmer, just below the Red River and the Oklahoma border in Muenster, where much of his production was.

By the time L. W. decided it was time to let Loyd take over, he had about 200 wells in Texas and Oklahoma. That was in 1969, when Loyd got out of the army. Since January of this year, the Powell wells have produced more than 6.3 million barrels of oil and five billion cubic feet of gas. That’s not anywhere near H. L. Hunt’s league, but it’s pretty high octane company for a poor boy from Smiley. L. W. did it without the services of a single geologist. Instead of geology, he practiced what he calls closeology, laying back and waiting for a wildcatter to prove a field before he went in with his rig. Closeology was simply spudding in as close to a producing well as the law and landowners would allow. Of course he had to pay more to get a lease, but it increased his chances of making a well. And it made him a rich man. Today he and Reba Jo have a beautiful home in North Dallas, but you can usually find L. W. up at the family ranch between Muenster and St. Joe chomping on a cigar and riding herd on the ranch hands. The Powell place embraces 5000 acres of rolling hill and valley, rich with 38 varieties of grass and fat with black Angus and Brahma cattle. It has been a paying ranch since L. W. quit killing himself raising world champion Appaloosa horses. The old man, who is 74, had his second heart attack at the ranch three years ago. Loyd happened to be there. He helped his father to his Cadillac, gunned the engine, and covered the 89 miles to Dallas and the hospital in 50 minutes. “Ever once in a while,” L. W. recalled, “I’d allow myself a look at the speedometer. That boy had the needle on a hundred.”

Loyd had no illusions on his coming of age as an oilman. There was no sense in pretending he was starting from scratch like his old man. It was a rich man’s game now, no matter where you drilled or how deep. His father had gone to the University of Hard Knocks so that Loyd could have the privilege of private school (St. Mark’s in Dallas) and college (University of Denver, SMU School of Business). And he was not entirely on his own and accountable only to himself. The old man kept some of the action and was free with his advice. His sister was in for a percentage, so they incorporated and called themselves the L & M Oil Company (Loyd & Mary). Mary was married to a doctor and wouldn’t be taking an active interest, so Loyd had a fairly free hand. Of course there were others to consider, like the old family friend and accountant, Robert Bozman, and the backers that Loyd would bring in on each venture.

Some operators never put their own money into a well, but Loyd didn’t believe in that. If he got a dry hole he wanted to be able to tell his partners that he was out some, too, sometimes 25 per cent and maybe even 75 per cent. He had one other rule. He wouldn’t ask a man to invest unless that man could stand to lose ten or twenty thousand, because you had to go in prepared to lose. Geology, although necessary, was no guarantee, and improved the chances of a strike by only a few percentage points. It was a high-risk business that only the established could afford. Once a well came in, however, it was self-perpetuating and profitable for a long time. Usually. The Powells’ oldest producing well, McKinley No. 1, has been pumping since 1938, and is the second best well they’ve ever had.

The other sobering aspect about Loyd’s ascension was that unless something really bizarre happened, he would have to content himself with poking through leftover oil patches. Oh, he would drill a wildcat once in a while, but it would be highly unlikely that Loyd Powell would ever open up something like a Spindletop or a Scurry Reef. Not because most of the oil was gone: there was more down there than had ever been taken out, but it was deep and difficult to get to, and would have to await new technology. One of the most spectacular dry holes of modern times was an attempt, in 1958 and 1959, to find oil at 25,000 feet in Pecos County. Loyd instead would go for shallow sands and play his old man’s game of closeology—economically it was the only way. He would also have to pick his way through a complex system of regulation and price control that would have baffled the oldtimers. Between locating a lease and bringing in a well there would be mountains of paperwork. The days of a handshake confirming a contract were over, gone with the likes of that great Fort Worth cavalier, Jack Grace. Even into the Fifties, Grace insisted on sealing a deal by shaking hands and looking you in the eye. Once he and J. Langford Shaw had come to terms over the phone, but Grace, never having met Shaw, insisted on flying out to Sherman to see him. Shaw was at the airport when Grace’s Beechcraft landed, Grace came down the ramp, shook Shaw’s hand, exchanged a pleasantry and was gone within five minutes, winging his way back to Fort Worth. “I just wanted to look that fella in the eye,” he explained to his pilot.

So much of that romance was gone. Well, Loyd was prepared for it. But what he was not prepared for was an almost sudden change of mood in the American people’s attitude toward industry in general and oilmen in particular. In 1969, the year Loyd set himself up at his father’s desk, public resentment at the fouling of our air and water took legislative form in the National Environment Policy Act, which toughened licensing requirements for nuclear and fossil fuel plants. Conservationists joined the environmentalists, and pretty soon people were saying shame, look what the industrialists and developers have done! They have used the body of the continent until the land itself, the good earth, was showing definite signs of depletion. People like the Powells had gone to the well too many times.

The domestic oilman was down in the dumps anyway, and this didn’t do him any good. Prices were down, costs were up, and operators began to get out of the business just as Loyd was coming into it. Manufacturers stopped making tools. Oil field supply houses began closing. Related service industries began laying off people. Domestic exploration declined as oil imports increased. It seemed to Loyd that the media played up oil spills and ecological damage from pipeline construction. Once L. W. Powell had been pictured as a producer, a provider. Now Loyd got the distinct impression that polluter and exploiter were the new appellatives for oilmen. Every time he picked up a newspaper or a magazine, some energy expert was predicting that we were running out of fossil fuels, that we had better conserve while converting to new forms of energy. Natural gas would be gone in 30 years, oil in maybe a hundred. Well, the Texas Railroad Commission was indeed prorating production, keeping it down to a few days a month. While around the world and even in the other states, the big companies were allowed to pump their wells at full blast.

It seemed to Loyd that the independent in Texas was being choked to death in the name of conservation. The incentive to drill just wasn’t there, and in the first four years of his stewardship, he attempted only a dozen wells. He was getting about $3.25 to $3.65 a barrel, which on the inflation scale amounted to a whole lot less than the $2.50 a barrel his dad was getting in 1955. He had two gas wells out in West Central Texas he couldn’t even connect—$100,000 sunk in two shut-in wells. The market out there was interstate and therefore regulated by the Federal Power Commission, and the FPC kept the price so low Loyd couldn’t afford to sell it. He would never get his money back. As far as he was concerned the industry was like a balloon with the air let out of it. Loyd spent a lot of time out on the ranch guzzling Dr. Peppers and staring at the stock, and Loyd wasn’t that turned on by beef.

One day he told his drilling contractor, Stumpy Stevens, that damn it he felt like a tit on a boar hog. Useless. Vestigial. Hell, Stubby knew what he meant. He was hurting too. Why he would throw in a string of free surface pipe if Loyd would let him drill a well. Free this, free that. It was just like when there was a lot of apartments in Dallas. The managers would give you a month’s free rent and throw in a couple of go-go girls on the side. Humm. Old L. W. listened and wondered if maybe the ranch might prove to be a better bonanza for the boy than all that oil and pig iron.

Now that he had gotten rid of his horses the old man was finding a tranquility in the country, in grass and grain and trees and cows and water, that he had never found tracking down oil leases and drilling. It was a high pressure business, the oilfield, and L. W. worried that Loyd worried so much. It would kill him if he didn’t relax. Loyd was single but he didn’t play like you would expect. He wore a Stetson and drove an Eldorado but he was no high roller. As a matter of fact, Loyd was careful with his money, maybe too careful. Course these were peculiar times. A man had to be patient.

And sure enough, Loyd’s luck turned, first in the shape of a girl from San Antonio named Celeste Altgelt from a fine old German family, rich from insurance and ranching. Loyd and Celeste hadn’t been married but a few months when the October War between the Israelis and the Arabs broke out. The Arabs, of course, put an embargo on oil shipments to the United States, and quicker’n you could say seismic the situation changed. America was screaming for oil to meet the energy crisis, and all the talk of profligate producers went down the drain of dry gas tanks. Production allowables were raised to all the pipes could bear, and local oil men started walking tall again.

Loyd Powell put it in high gear. He hadn’t drilled in fourteen months, but now, in quick succession, he drilled twice—first a wildcat that was dry as a mummy’s tomb and then a gas well that Loyd decided to shut-in until the government let the price go up. The dry hole wildcat cost Loyd and his partners $80,000; the latent gas well $60,000.

Oil had jumped to $10 a barrel, but dammit there was talk in Congress of a crude oil price rollback. One day in February Loyd called in his secretary, Della Blankenship, and dictated a telegram to Senator Henry M. Jackson in Washington. He warned the senator that a price rollback would be disastrous and counter-productive, that marginal wells would have to be plugged again and that independents would be discouraged from further exploration. A month and eight days later, Sen. Jackson replied by letter:

While I recognize the role of higher prices in stimulating the development of new oil supplies, I also recognize the need to protect the consumer and the economy from the impact of excessive price increases for petroleum products. The Committee’s hearings and investigations make clear that there is no justification for the unprecedented price increases for crude oil and petroleum products in recent months.

The senator went on to add that he was proposing legislation to put a ceiling on crude oil. Loyd made copies of Jackson’s letter and mailed them to his various backers, adding his own comment that Jackson was ignorant when it came to the oil business. “I wonder,” Loyd closed, “when Henry Jackson put his money where his mouth is and invested in a wildcat?”

Loyd didn’t drill for six months. It wasn’t because he didn’t want to. He had $70,000 tied up in leases and was anxious to prove a pocketful of other prospects. His problem was pipe. There wasn’t any. Domestic drilling had stepped up 25 per cent, and the steel companies weren’t prepared for the demand. Besides, they were committed to foreign producers. Loyd kept hearing stories of black market pipe stacked to the ceiling in warehouses owned by brokers, of a cajun in Louisiana getting iron from Spain, but actually finding pipe was as hard as striking an oil sand. He had Rohmer and the boys pull 5400 feet of casing out of an old well in East Texas, and he got some sucker rods and some surface pipe, but hell he still needed 100,000 feet of tubing, just more of everything.

And then he got it, just enough to start, and in July he sank that $60,000 into the Palo Pinto dry hole Gary Bishop photographed. What did he do? He and the Carter Company moved the rig to another site a few miles away, and as of this writing, Loyd’s latest well is registering 100,000 feet of gas pressure, so he may have something. It’s not fantastic but at least it’s encouragement.

And Loyd’s not complaining. The oil business right now looks better to him than it ever has in his memory, if the government will just leave it alone and the majors don’t mash the independents into the ground. The big explorers are starting to come back home, now that they are finding foreign governments more hostile. Loyd is so optimistic he has moved L & M into a new Energy Center complex north of downtown. There he and Bozman and Mrs. Blankenship are surrounded by other oilmen who share their excitement. Someone is even setting up a geology library. Loyd is back and forth between the field and the office, his pockets full of lease agreements, his valise full of maps, and his belly full of chicken-fried steak. He loves to read what he calls his Bible, The Oil and Gas Journal, and to pore over what he calls his Dun & Bradstreet, The Oil Directory of Texas and Production Survey. The directory separates the men from the boys, and it fascinates Loyd. The other day at the office he was feeling pretty good. He had a new pair of Nocona boots and Celeste was at Neiman’s having her hair streaked. They were getting ready to make the river fiesta in San Antonio. Loyd bent over the directory and went through its pages in a random fashion.

“Boy, there’s some real stories in here. What you can do is look at this year’s book, and then look at last year’s, and you can see whether they’re up or down. Our gas is holding about the same but our oil is down some. But there’s some people in here you’ve never heard of! I don’t even know who they are. Like this guy here John Cox out of Midland. I don’t know where he comes from or who he is or anything. He’s got over… Well here’s Edwin Cox. Jake Hamon. John Cox… 403,000 barrels a month; that’s a little over 13,000 barrels a day and that’s a hell of a lot of money. I don’t know how much of that he actually owns.

“Ah, here’s a little company called Cokinos. It’s a fun company just gettin’ started. There’s a lot of little companies. I don’t know. The Kennedys are in here under some little company. Can’t remember what they call it. Just getting started. Lot of stories in here. Gonna be some better ones. Risky maybe, but a lot of romance. It’s just exciting to go out and drill you a well and smell oil nobody’s ever found. It’s been there for millions and millions of years, and ever’ drop you find goes into the national oil stream and supplies a guy in North Carolina with five gallons to go see his grandmother. And we’re ridiculed so bad. But that’s just one of the things you have to accept. We’re in the minority and always will be.”