This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

It was the kind of farm auction that mainly countrymen and a few implement dealers attend, for it was in an out-of-the-way part of the upper West Cross Timbers, and the classified ad announcing it in the Fort Worth paper had mentioned no churns or crocks or wagon wheels or other venerable curiosities of the sort that lure crowds of city people to such affairs. There was to be a sellout of everything on hand, including the farm itself—“125 a. sandy land, 45 in cultivation, rest improved grass and timber, 2 tanks, barn, new brick home 3 b.r. 2 baths, all furnishings.” Though it lay eighty or ninety miles north of my own place and I am not much addicted to auctions of that kind—melancholy events nearly always, aromatic with defeat and often with death—I drove up that Saturday in late winter because among the items listed for sale was an Allis-Chalmers grain combine of the antiquated sort that is pulled and powered by a tractor.

In my rough area those relatively small harvesting machines, none of them less than about thirty years old, are still in demand if they have been kept in working order. Most of our field land is in small tracts strewn about between the hills, and even when you can find a custom combine operator willing to bring his shiny self-propelled behemoth to your place for the sake of reaping just twelve or twenty or thirty acres of oats or wheat, he will most likely balk when he gets a good look at the narrow rocky lanes and steep stream crossings through which it must be jimmied to arrive at its work. So we often let cattle keep on grazing winter grain fields instead of taking them off in March, or we cut and bale the stuff green for hay. But sometimes when you’d like a bin full of grain to carry your horses and goats through winter and maybe to fatten a steer or so for slaughter, you wish you had a bit more of the sort of control that possession of your own varied, if battered, machinery gives.

A front had pushed heavy rains through the region the day before and the morning was bleak, with gray solid mist scudding not far overhead and the northwest wind jabbing the pickup toward the shoulder as I drove. It grew bleaker after I left our limestone hills, with their live oaks and cedars that stay green all year, and came into country where only a few brown leaves still fluttered on winter-bare post oaks and briers and hardwood scrub. Sandy fields lay reddish and wet and sullen under the norther’s blast, and in some rolling pastures, once tilled but now given over to grass and brush, gullies had chewed through the sand and eaten deep into the russet clay underneath. Outlying patches of such soil and vegetation occur even in my own county, and for that matter since childhood I have known and visited this main Cross Timbers belt, a great finger-shape of sand and once-stately oak woods poking down into Texas from the Red River. But it has always had a queerly alien feel for me, in part undoubtedly because I grew up surrounded by limestone and black prairie dirt and the plants that they favor and, with the parochialism dear to the human heart, I simply like them.

Others for their part prefer the sand, and locals of this stamp seemed to make up a majority of the 150 or so people who were standing around in clumps when I parked alongside a narrow dirt road, slithered up a clay hill past a low, suburban-style house, and entered the farmyard where, arranged in a wide ellipse, stood the relics and trophies of someone’s ruptured love affair with the soil. Bushel baskets and nail kegs filled with random hand tools and pipe fittings and bolts and log chains and mason jars and whatnot. A section harrow, three tandem disks, plows of various sorts, a row planter, a cultivator, a grain drill, a hay swather, two balers, of which one was riddled with rust and good only for parts cannibalization, a corral holding twenty or more good crossbred beef cows with their calves, a tin barn half-full of baled Coastal Bermuda and, as the ad had promised, other items too numerous to mention, though I can’t help mentioning one: a large and gleaming tuba. Much of the farm machinery had a scarred third-hand look quite familiar to me, for it was the kind of stuff that we marginal small-timers tend to end up with, but this fellow had invested in a much greater variety of it than I had ever ventured to, and here and there sat something fairly expensive with the sheen of relative newness on it—a good medium-sized tractor, a heavy offset-disk plow, a fancy wheeled dirt scoop with hydraulic controls.

The blocky orange shape of the A-C combine loomed at the far end of the ellipse, and as I walked toward it, wind-hunched locals in caps and heavy jackets and muddy boots viewed me with taciturn distaste: another outlander plunked down among them to run the bidding up and to make them shell out more for whatever it was they had their eyes and hearts set on. Two of them were studying the combine and stopped talking when I came near, but started again in lower tones after I began jiggling levers and checking belts and chains and opening flaps to peer at intricacies inside the big box. Its paint job was not bad, so it had been kept under cover for at least some of its long life, and those metal working parts that came in contact with moving grain and straw and chaff were shiny-bright in testimony, I thought, of fairly recent use, a hawk-eyed Holmesian observation confirmed by one of the other interested parties.

“They cut twenty-four acres with it last summer,” he said to his friend. “I know because I seen it. It didn’t blow hardly no oats out on the ground.”

“What about the canvases?” I asked, for those wide ribbed belts that elevate material from the cutter bar to the machine’s Rube Goldberg interior matter greatly and are expensive to replace if worn out or rotten from neglect.

He snapped his stubbled jaw shut and glared but had to answer, minimally. “In the barn,” he said.

I found them on a shelf there and they looked all right too. The combine was worth trying to buy, though while examining it I had begun to have misgivings about towing its eleven-and-a-half-foot width over the fifteen miles of narrow, muddy, humpbacked roads, with water-filled ditches, that I had traversed since leaving pavement, and then maneuvering it through the Saturday traffic of three fair-sized county seats that stood between this place and home. However, these thoughts were cut short by the crackle and burp of a bullhorn near the house and a jovial brassy voice announcing the auction’s start. Together with most of the others I moved toward the scarlet pickup from whose bed the bullhorn blared, but a few dogged figures remained beside implements or other objects they had chosen, establishing what they hoped was priority and waiting for the sale to come to them.

The auctioneer was a pro, as nearly all are these days, stetsoned and paunched and lump-jawed with sweet Red Fox tobacco. He knew a few of the people present—Western-clad, cliquish, probably dealers—and jollied them by name between spells of ribba-dibba chanting and exhortation to higher bids as an assistant held up the containers of smaller stuff to view and they were sold off batch by batch. Loading the cold moving air with urgent sound, his amplified voice fanned greed and fuzzed rational thought among less inured listeners, as it was intended to do, but the crowd was not a prosperous one, and at this early stage the bidding stayed low. I felt a twinge of avarice as a basket of good wrenches and pliers and screwdrivers and such, worth probably $80 or $90 at retail, went for $4.75, but forced myself into the reflection that I already owned at least one specimen of every tool there—as, probably, did the grim skinny oldster who bought them and bore them away in triumph. The pickup inched forward along the line of ranked items as they were sold, and when it reached the farming implements the visiting dealers moved in for the kill, and things began to get hotter, to the disgruntlement of us amateurs. Thwarted, a young farmer delivered a hard sodden kick to the beam of the handsome yellow offset disk over which I had earlier seen him practically salivating, but for whose sake he had been unwilling or unable to top the $750 that it brought, about half of its market value even second-hand. “Them son of a bitches sure make it hard,” he said.

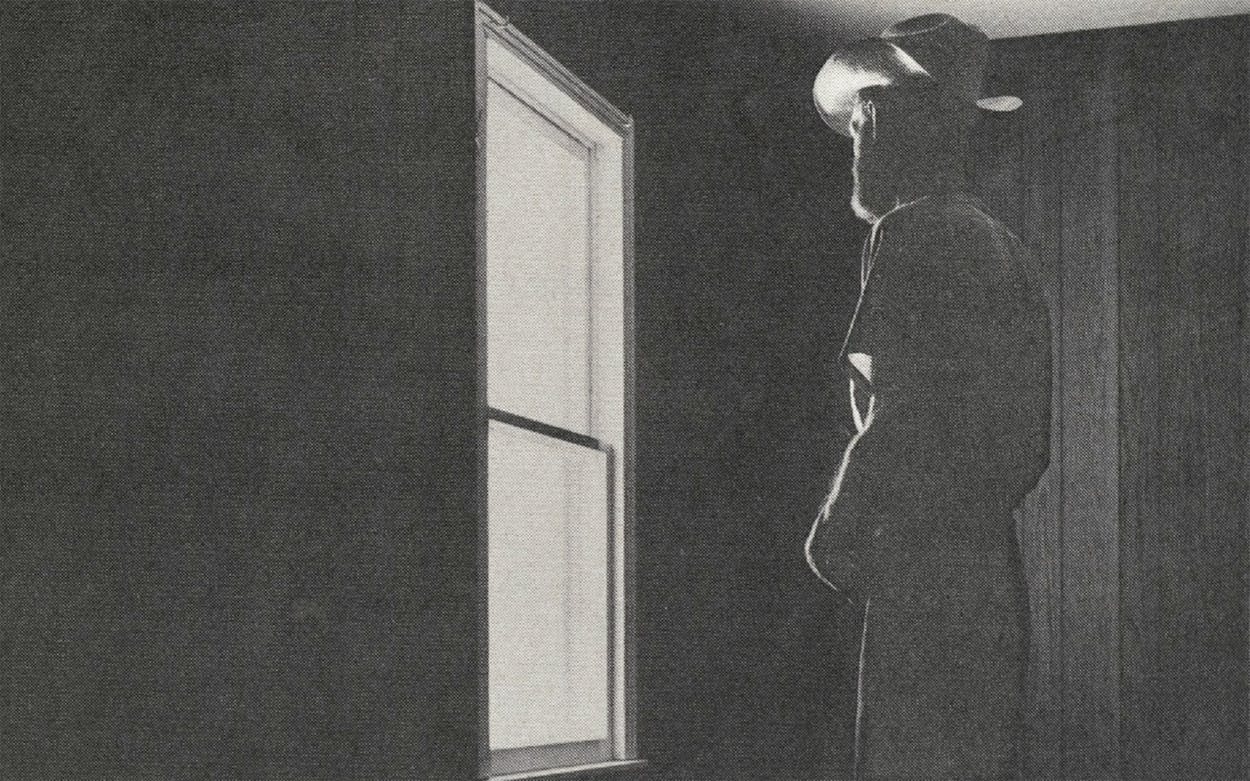

I was looking at a hatless thin-clad man who sat on the edge of the pickup’s bed beside the auctioneer. He was in his forties, pale and slight and balding and with the pinched waxy look of sickness on him, maybe even of cancer, and as I watched his dark worrier’s eyes swivel anxiously from bidder to bidder and saw the down-tug of his lips when something sold far too low, I knew very well who he was. He was the erstwhile lord of this expanse of wet sand and red mud, the buyer and mender and operator of a good bit too much machinery for 45 arable acres, the painstaking nurturer and coddler of those fat penned cows, the player perhaps of a tuba, the builder of a hip-roofed brick-veneer castle, 3 b.r. 2 baths, from which to defend his woman and his young against the spears of impending chaos. Except that chaos, as is its evil custom, had somehow stolen in on him unawares and confounded all his plans. He was, in short, the Loser.

“I got a scoop,” the auctioneer cried. “I got a big red dirt scoop. I got a great big pretty red dirt scoop that’ll dig you a ditch and build you a terrace and haul one whole cubic yard of gravel or sand up out of your creek bed and all you got to do is touch a little lever and she dumps it right where you want it. Eight-ply tires and the whole thing just about new from the looks of it. What you say, men?”

“Thirty-five,” ventured one of his auditors in a tentative voice. I saw the Loser twitch and tense, and surmised that to him, for whatever reason, the scoop meant something special, as occasional implements do.

“That ain’t no bid, it’s an insult,” said the auctioneer.

“Cylinder’s busted,” the bidder answered with a defensive air, and I remembered noting that the arm of a hydraulic piston on the scoop was bent and useless, though repair or replacement probably wouldn’t cost much.

“Urba durba dibba rubba hurty-fie,” said the auctioneer in abandonment of the subject. “Hurty-fie hurty-fie hurty-fie who say fitty? Fitty, fitty, fitty, fitty, durba dubba ibba dibby who say forty-fie? Forty-fie, forty-fie . . .”

“Forty!” somebody yelled.

The Loser rose trembling to his full five foot seven or so beside the large auctioneer, and his unamplified voice was reedy, but the feeling behind it carried it out over the crowd. “Godamighty, boys,” he said. “I paid out three seventy-five for that thing not six months ago, and the fellow I got it from, he hadn’t never used it but twice. Another fellow come by one day when I was digging a tank with it, and he wanted to give me five hundred. That there’s a good machine. I just can’t see . . .”

And sat down, staring at his toes. As if in imitation, many in the crowd looked earthward toward their own muddy footwear, and an almost visible feeling enveloped us like thick gas, and was not blown away by the steady wind. Faced with erosion of the mood he had been building, the auctioneer spat brown juice and stared briefly, cynical, toward the gray horizon before returning to the fray. “Man’s right,” he said. “Listen to him, boys. It’s a good scoop. You got to remember what the Bible says, ‘Though shalt not steal.'”

Urba dibby, etc., and in the end the scoop fetched ninety bucks, which may have been a little more than it would have brought without the little man’s outburst. Nobody, it seemed, really wanted a scoop, and the dealers for their own private reasons were not interested. The Loser shortly thereafter got down from the pickup and went to what was at that point still his house, followed by numerous furtive eyes.

“Poor booger,” somebody said.

In large part our lingering fog of feeling was made up of shame, of the guilt most of us had brought along with us to the sale, knowing that if we found any bargains there it would be because of someone else’s tough luck. Some of us had not been aware that we carried this load until we heard the Loser speak, but it was waiting there within us nonetheless, needing only a pinprick to flow out.

But there was another thing too, less altruistic and thus maybe stronger. But for the grace of God, there through the red mud trudged we, stoop-shouldered toward a brick-veneer house soon not to be our own. At three o’clock in the morning, once or twice or often, may of us had known ourselves to be potentially that small pale man as we sweated against the menaces of debt not to be covered by nonfarm earnings or a job in town, of drought, of a failing cattle or grain or peanut market, of having overextended ourselves on treasured land or machinery or a house, of perhaps a wife’s paralyzed disillusionment with the rigors of country life, and above all of the onslaught of sickness with its flat prohibition of the steady work and attention that a one-man operation has to have, or else go under. The Loser had made us view the fragility of all we had been working toward, had opened our ears to the hollow low-pitched mirth of the land against mere human effort.

No, I didn’t get the little A-C combine. If all of us there had been amateur buyers I would have had it for $175, for that was where the other countrymen stopped bidding. But a dealer type in sharkskin boots and a spotless down jacket and a large black hat stayed with me, as I had suspected he would, for the old machine with a bit of furbishing would be worth maybe $700 or so on his lot. Enjoying the growth of his cold resentment, I carried him up to $400 and quit, partly because of my doubts about bulling that orange hulk through ninety difficult miles and perhaps getting caught by darkness, but mainly I believe because thinking about the Loser and all that he stood for had made me start wondering hard if I really, honestly, badly needed the damned thing.

Nor did I stay to watch the bidding for the cattle and the house and the land. What I wanted, and what I did, was to flee back home to black dirt and limestone country, where I could have a drink beside a fire of live oak logs and consider the Loser’s alien, sandy-land troubles with equanimity from afar.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Farmers