A middle-aged woman sat alone on a plaza bench in El Paso, her face flushed from the heat, her eyes rimmed with smeared mascara. She stared vacantly into space, looking as if she needed a break from life. On her lap was a vinyl banner emblazoned with an image of her fawn-eyed daughter, Mónica Janeth Esparza—the same sign she’d held against her chest during so many other marches and demonstrations, a blown-up version of the missing-person flyer that was still papered all over Juárez more than two years after the city had swallowed the eighteen-year-old whole.

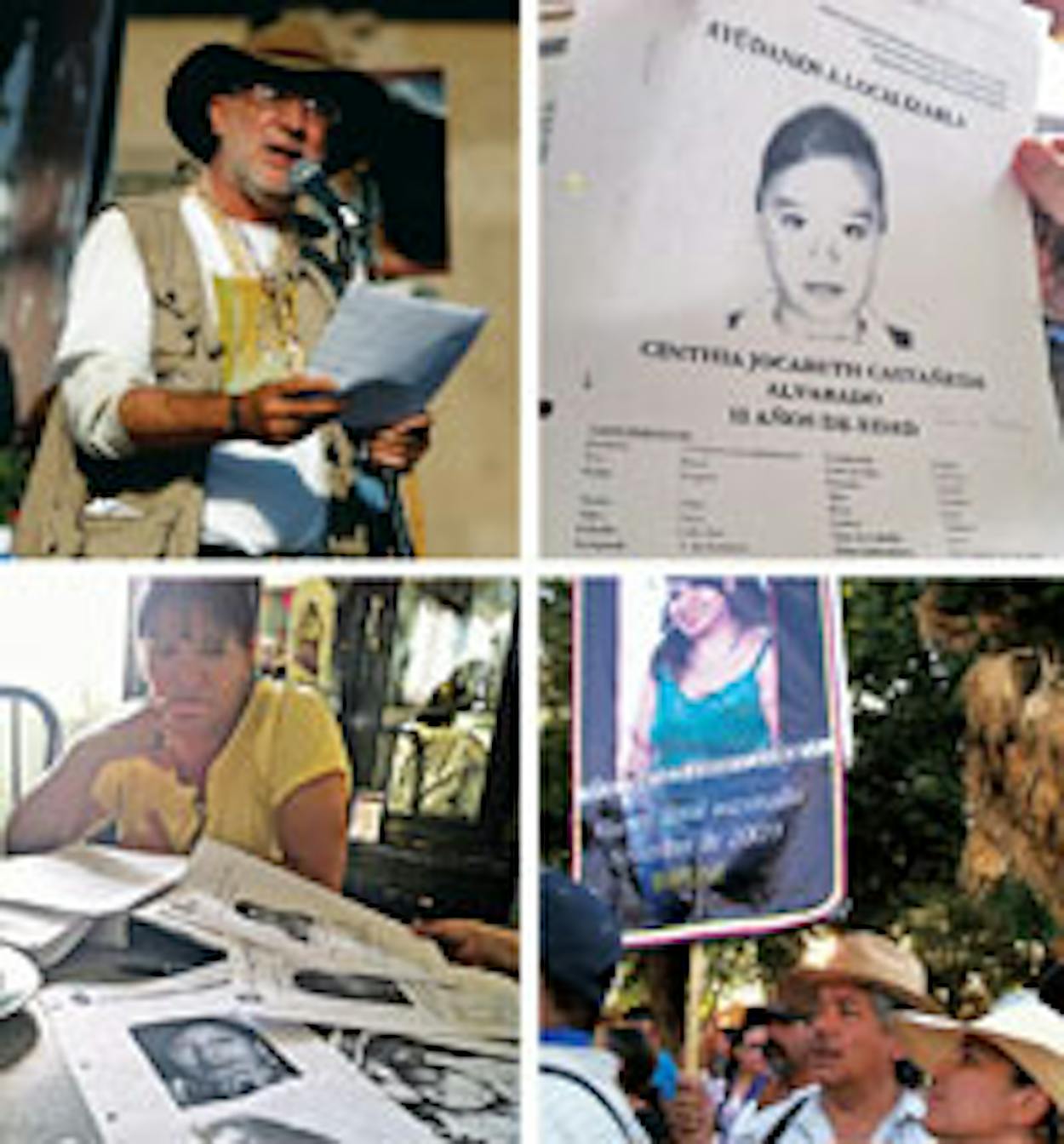

The June temperatures were oppressive, but hundreds of residents from El Paso and its sister city had turned out on San Jacinto Plaza that morning to listen to the words of a bearded Mexican poet named Javier Sicilia. Just two and a half months earlier, Sicilia’s 24-year-old son and four friends had been forced by strangers out of a bar in Cuernavaca and later found dead, their heads wrapped in packing tape. Sicilia had declared an end to his poetry and channeled his grief into a “peace revolution,” a grassroots movement he launched to protest the Mexican government’s strategy in a drug war that had claimed some 40,000 lives. With the international community watching, Sicilia led other bereaved survivors in a seven-day mass caravan from Cuernavaca to Juárez, finishing with a rally in El Paso on June 11.

Olga Esparza, who had last seen her daughter in March 2009, had joined the other relatives of victims onstage, and they had clutched one another’s arms in anger and sorrow. But now, the rally done, she felt the emptiness creep back in. At least Sicilia had had a body to cry over. She had nothing. All she knew was that Mónica had left for class one day and never returned home.

A young woman vanishing in Juárez was nothing new, of course. It was the city’s claim to fame. Reports that local women were disappearing and being murdered first surfaced in 1993, and by 2005, activists had counted more than three hundred victims. Many women were killed by possessive boyfriends or random strangers. But others had just disappeared; most were later found raped and strangled, left to decompose in the desert heat. As authorities failed to definitively solve any of the cases, sensational theories ran rampant, and soon this targeted violence had earned the term feminicidio. Across the world, the deaths became the focus of protests and prayer vigils, conferences and benefit concerts, art shows and dissertations (including my own), and even a movie by Jennifer Lopez and a novel by Roberto Bolaño.

Within Mexico, the outcry had led to a new women’s movement. Congressional committees began tracking female killings everywhere in the country, and laws were made to protect women and ensure gender equality. Multiple government entities and posts were created, including that of a special federal prosecutor who would investigate human trafficking and crimes against women. And in late 2009 came the most important response of all: The Inter-American Court of Human Rights, based in Costa Rica, heard three of the Juárez cases and issued a scathing indictment of the Mexican government, ordering a thorough transformation of its prevention, investigation, and prosecution of violence against women.

Yet somehow, as Olga knew all too well, the reality in Juárez hadn’t changed. The government had yet to comply with the court’s ruling. The public, wearied by the lack of answers and the overblown rhetoric, had grown indifferent and jaded. And then there was the widespread violence sparked by drug cartels in 2008. The body count soared from more than three hundred in 2007 to more than three thousand in 2010, and the sheer reach and brutality of it all had forced a drastic shift in attention.

But young women were still disappearing, and in even greater numbers. Since early 2008, close to one hundred remained missing, almost all of them adolescents. The only crucial difference was that no one was finding their bodies. In the face of her loss, Olga had decided to believe that Mónica was alive. Eighteen years, she mused, as the park cleared out. And Juárez was no closer to the truth.

Olga has dark, intense eyes, and her circumspect stares belie her warmth. Two days after Sicilia’s rally, she welcomed me into her home in a working-class neighborhood of Juárez, a two-story house with white tile floors and pale-green walls. Near a staircase hung a large, glossy portrait of Mónica in a pink quinceañera dress.

I had been making visits to Juárez for eight years, both as a journalist and a graduate student, to write about the city’s missing women. But as I sat in Olga’s home for the next three hours, I’d hear some of the most chilling stories yet. Two other mothers joined us, Norma Laguna and Bertha Alicia García, as well as a lawyer named Francisca Galván. The four formed the core of the Committee of Mothers of Disappeared Girls, a newly minted coalition of twenty women.

Bertha’s daughter, Brenda Berenice, was seventeen when she left home one morning in January 2009 to look for work. The girl had given birth to a baby boy the month before, and she hoped to get hired at a jewelry store downtown. Getting there required a long bus ride, so when her father called her cell phone shortly after noon, Brenda still had a ways to go. Her mother tried her again around two-thirty; this time someone answered but immediately hung up. “I kept dialing,” Bertha recalled. “It was voicemail, voicemail, voicemail.” She hoped for the best: Maybe the store owners had asked her daughter to start that very day. But when Brenda failed to return that evening, the family spent the night searching every bus that arrived from downtown. The next morning, at the jewelry store, they were told that Brenda had not been by.

Mónica disappeared two months later. A business student at the local university, she had told her parents she was going to spend the afternoon working on a group project at a friend’s house. Her mother called her at around three o’clock. “She said she was on her way, but it didn’t sound like she was on a bus,” Olga said. “It sounded like she was in a car.” Mónica never answered her phone again.

And then there was Idali. The nineteen-year-old vanished this past February after visiting her brother in prison, where he’d landed on false charges. She’d left the prison at one o’clock, and “we never heard anything again,” said her mother, Norma. Two days earlier, Idali had visited a modeling agency near the bus terminal downtown, to sit for photos as part of her work application. Near the end of the shoot, the owner had asked if she’d pose in lingerie and said he could get her work doing calendars somewhere far from Juárez. Idali had refused and fled in fear. But she had lost a ring during the shoot. Since the bus trip home from the prison included a transfer downtown, Norma wondered if maybe she’d gone back to retrieve it.

In all three cases, state government officials had activated a Protocolo Alba, Mexico’s version of an Amber Alert. They posted flyers for each of the girls, interviewed their families, and issued a search warrant for the modeling agency. There, investigators discovered more than a hundred girls’ applications, including Idali’s, and interviewed two who said they’d taped a commercial with her for a car parts store. The girls also claimed they’d been offered higher pay to have sex with men. Still, the officers said, none of the evidence implicated the owner.

The mothers vowed to keep searching. “I don’t know if it’s because it terrifies us, but we don’t get into feminicidio,” said Francisca. “We prefer the term ‘disappeared.’ As long as we don’t find them, it’s our hope that they’re alive somewhere. That’s our mantra: alive, alive.” Francisca did detect a pattern among the victims: thin, pretty, naive. Many had disappeared downtown. Though she wouldn’t spell it out, she suggested the culprits were sex traffickers who were working the same areas as the city’s drug gangs. They might, she theorized, even be the same crime rings that were active eight years ago, when a rash of girls vanished from downtown, many from around the bus terminal. Years of impunity would have boosted their power and extended their reach. When I pointed out that those women had been found dead, Francisca’s voice trailed off. “There’s just so much to all this,” she said, “that I prefer to maintain hope.”

A month later, on July 13, yet another girl disappeared. An alert was issued. Again it yielded nothing. This time, the girl’s family and members of Olga’s coalition staged demonstrations outside the state prosecutor’s office to demand action. Then the unexpected happened: On July 22, more than three hundred state and federal police agents descended on downtown, blocking off streets in the red-light district and raiding strip bars and cheap motels. Dozens of people were hauled to the police station, and federal agents quickly put out a bulletin saying that 29 establishments had been raided, 20 underage girls had been rescued, and 1,030 people had been detained in connection with sex and human trafficking.

But the state government soon issued its own version of the story: Only one fifteen-year-old girl, a runaway, had been picked up from a hotel, along with four other minors who were found in the area. There were no arrests. Some four hundred workers and clients had been fingerprinted, given medical checkups, and released.

The conflicting reports laid bare the porosity of the Mexican justice system, and when I spoke with Francisca afterward, she told me that the abducted girls were likely not being held downtown. The area was just where they were ensnared with false promises of work. That fact alone, she told me, could be used to advance a larger investigation into underground criminal networks—if only the authorities would try. She sighed. She wished the FBI would step in, or that she and the victims’ mothers had the resources to conduct their own investigation.

“I’ve come to the conclusion that our government already knows what we’re telling them,” said Francisca. “They have the ability to resolve it. I think they just don’t want to.”

A few days before leaving Juárez, I drove downtown, searching unsuccessfully for Idali’s modeling agency. I’d had an unsettling encounter myself on these streets in 2003. Standing on an empty sidewalk during the quiet lunch hour, I had been approached by a man selling candies in a basket. “Excuse me, are you looking for work?” he’d asked. The question had paralyzed me even then, and now, knowing the countless stories of daughters who’d gone in search of jobs and never returned, it seemed newly relevant. As I watched a handful of teenage girls walking down the street after school, I was acutely aware of the many modeling agencies, massage parlors, and pay-by-the-hour hotels that surrounded us. There were likely underground markets for adolescent girls all over Juárez.

Yet today, the government still has no investigative plan, no criminal profile of possible suspects. When I met with Ricardo Esparza (no relation to Olga), the state official who oversees missing-person cases in the city, I’d asked him if he tracked not just where girls disappeared but also how they’d gotten there or what they’d been doing. “Not necessarily,” he said. He was limited in his jurisdictional authority, he told me, but maybe I could check with the federal police.

Later I went to see Irma Monreal, a woman whose 15-year-old daughter, Esmeralda, was abducted and killed in 2001, her body found with seven others. In April 2009 I’d watched Irma testify before the Inter-American Court. Now she told me about how, last November, local TV stations had reported the fact that she and two other families would receive thousands of dollars in damages from the Mexican government, which made her fear for her safety. Then, in December, she and her 21-year-old daughter, Zulema, had experienced separate kidnapping attempts in which men had tried to force them into a car—a new pattern of violence that seemed to be on the rise.

It had all been too much. Irma had decided it was time to move her family to her home state of Zacatecas. But on the way there in January, one of her sons accidentally flipped his car on the road, killing two of Irma’s grandchildren. As we talked in June, she seemed more hollowed out than ever. She said her court victory had given her hope, only to have it crushed by the government’s failure to enact any real change.

“What I’d never wanted was for any more girls to be in Esmeralda’s shoes or for any families to suffer like mine has,” she said. “I’ve made so many efforts, and what for?”

And so, when Sicilia had arrived in Juárez the previous Thursday and held a ceremony at the very site where her daughter’s body had been found ten years earlier, Irma had briefly contemplated going. Then she changed her mind.