This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

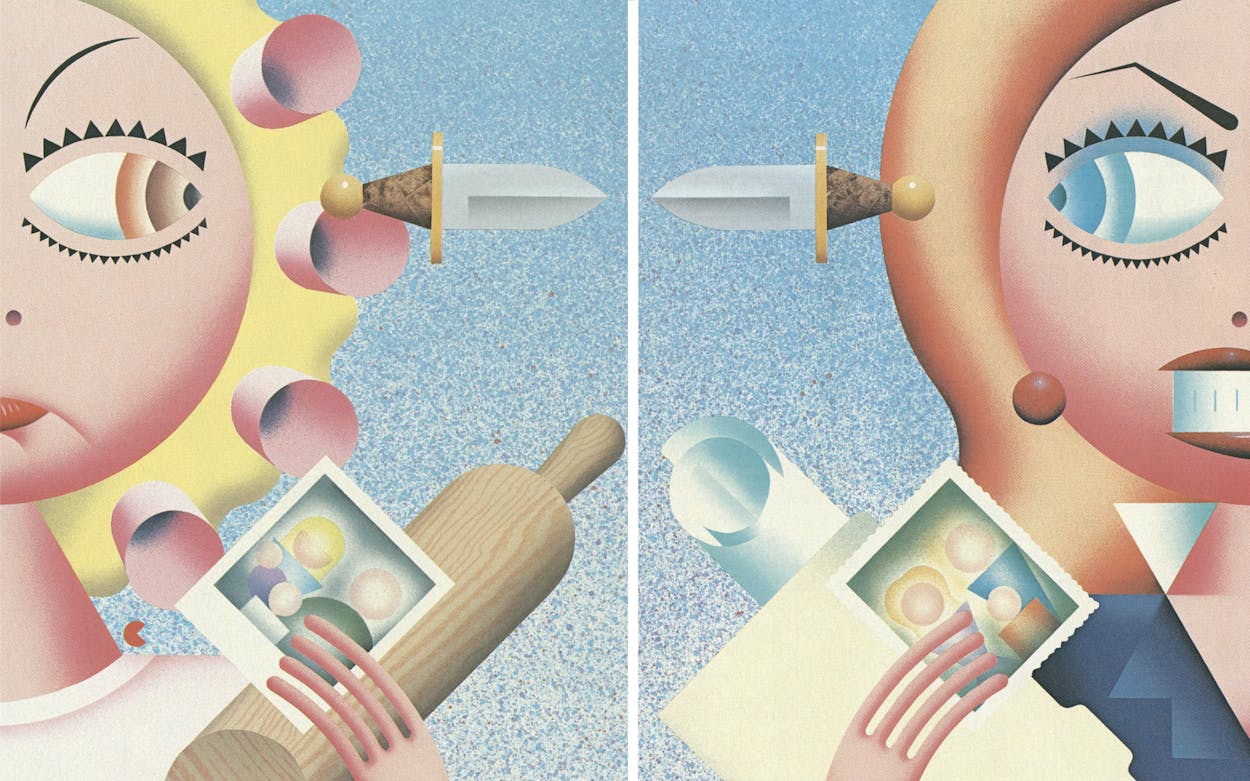

Until the head of iceberg lettuce came flying through the air on a straight course for my face, I did not realize I was at war with other mothers.

It happened one frantic Friday night, when I hurried into the grocery store with my two small children in tow. The store was crowded and noisy. Dozens of other mothers with small children in their carts were wandering the aisles, stocking provisions for the weekend. I balanced my infant son in the front of the cart and handed my four-year-old daughter a cookie. After a week at work, it was good to be with the children—even there in the chaos of the grocery store. Standing at the dairy case, I felt my invisible armor of anonymity penetrated by another mother’s stare. I ignored her and pressed onward, toward the chips and hot sauce. The woman did not go away but followed me through the store. Through row after row of Cheetos, potato chips, and tostadas, I felt her stare.

Finally I turned and faced her. She was a blonde in her mid-thirties with a full, oval-shaped face. She wore a pale-pink sweatshirt with matching sweatpants. The sweatpants were splotched with purple tempera paint. She looked like she had come from a long day of pouring juice and wiping up spills. She too surveyed my uniform: a red wool suit, an oxford shirt, and navy pumps. I felt the sting of her first impression: She pegged me as a working mom. We were total strangers and mirror opposites. Yet something about her seemed familiar.

A few moments later, she and her two children were standing in a long line, waiting to check out. I wheeled our cart into the check-out station next to hers. “Excuse me,” I said, across the candy counter. “Do I know you?” She said she wasn’t sure but had been trying to place me. Thinking I might have met her through work, I posed the most innocent of questions: “What do you do?”

Instantly, I knew I had asked the wrong thing. Suddenly, her body went rigid, and a look of rage appeared on her face. She picked up the head of lettuce and threw it at me, but it was her words that found their mark. “I stay home with my children,” she hissed, “which is what you should do.”

So much for sisterhood. So much for tolerating another woman’s choice of lifestyle. She was an angry stay-at-home mom. I was a guilty working mom. We were natural enemies.

The episode in the grocery store was an extreme example of a simmering but rarely discussed war between mothers who work and those who stay at home. After the lettuce attack, I sought out mothers of all stripes—working, nonworking and part-time—and asked them about their conflicts with other mothers. At first, most of the women I talked to said they had no conflicts. After all, this was the age of tolerance. The struggle of the women’s movement was about giving everyone the right to make her own choices. But five minutes into our conversations, some catty little gripes would pop out. A writer for one of the San Antonio newspapers realized that at her children’s school the telephone chain was organized along partisan mommy lines: The stay-at-home moms called one another, and the working mothers called one another, with almost no crossover between the two groups. An Austin stay-at-home mother confided that she was sick and tired of asking working mothers to help out with school parties. “I’d rather do the whole party myself than ask a working mom for help and have her show up late with a lousy bottle of Seven-Up,” she said.

This is a war fought primarily by privileged opponents—women who do have a choice. Most American women are like most American men. They have to work; their families need the money. Today only 14.4 percent of American families fit the traditional fifties model of Dad going off to the office and Mom staying home with the kids. On one side of the front lines of the Mommy War are women who work because they want the psychic satisfaction of a career as well as a paycheck. On the other side are women who view their home and children as their jobs.

Still, the conflict is everywhere. You see it in the nation’s big debates. Lobbyists for stay-at-home moms think it’s unfair for the federal government to give tax breaks to working parents. Hence, President Bush has proposed a $1,000 child-care allowance for both low-income mothers who stay at home and those who work. The war broke out in the open in the recent controversy over the Mommy Track—the proposal, first published in the Harvard Business Review, that suggested that the workplace be divided between “career-primary” women and “career-and-family” women. Working moms viewed the Mommy Track as evidence of a backlash against women who are struggling to juggle families and jobs. Stay-at-home moms saw it as proof that they were right all along —feminist idealism aside, it’s the women who raise the children.

You see it in the polarization of mommy literature. Working moms pore over magazines and books that bolster their point of view; so do stay-at-home moms. In the April 1989 issue of Ms., working moms read Barbara Ehrenreich’s “Stop Ironing the Diapers,” a humorous step-by-step guide to raising children at home in our spare time. The other side subscribes to Welcome Home, a monthly publication that pitches itself to “the smart woman who has actively chosen to devote her exceptional skills and good mind to the nurturing of her family.” In a recent “From the Heart” essay, Welcome Home editor Penny Snyder had this to say about the Mommy War: “I’m not certain there ever will be more than a glimmer of understanding between the two sides, but we mothers must work for acceptance of each other even if we don’t understand each other’s choice.”

Regardless of her station in life, every mother feels injured by the question What do you do? That question has a chilling effect on the best dinner parties. Stay-at-home moms despise the What do you do? question because they know full well that the world at large doesn’t value what they do. Working mothers who listen as the stay-at-home moms answer, “I’m a mother,” feel suddenly selfish and inferior. Now both groups of women—the stay-at-home moms and the working mothers—are equally conspicuous. They can ignore each other no more; each regards the other as her shadow side, the embodiment of the choice she did not make.

At Jungle Jim’s, a party house for children in the northwest suburbs of San Antonio, there is a dense undergrowth of several hundred knee-high children, all eating sticky pizza and running from joyride to joyride. Above the squeaky roar, I hear my daughter’s distinct shriek as she whizzes by on the roller coaster. We are here for a friend’s birthday party, only one of about a dozen such parties going on simultaneously. The kids are in heaven. The moms walk the social tightrope.

I instantly spot the other working moms. All of us are still dressed for work—no khaki or denim skirts—and we’re pacing the giant room like nervous cats. It is four o’clock on a weekday. Just getting here has been a logistical nightmare. It meant leaving work early, picking up Maury from school, buying a present, and hurriedly wrapping it in the car, all accomplished through the haze of diffused guilt about the day’s work left undone. The other option—missing the party—is unthinkable. Maury would be devastated.

Across the room I see district judge Susan Reed, one of Bexar County’s criminal judges. Reed is a working-mom archetype. She is successful in her career, is married to a lawyer, and has a full-time housekeeper. Reed jokes that after a busy weekend with her four-year-old son, Travis, she becomes “Travisized” and returns to her bench in order to rest. She has everything that modern women aspire to—marriage, a meaningful career, money, and motherhood. Yet here she is—a social outcast—watching her son ride a miniature airplane.

Later I ask Reed if she feels uncomfortable in such situations. “The truth is,” she confides, “I’d rather face a notorious drug dealer or murderer in my court than have to go to one of those parties. I don’t know what to talk to the other mothers about. They feel intimidated by me. I feel intimidated by them. I try to talk about kid stuff, but I always go home feeling like a social failure.”

Reed’s experience illustrates a hidden dimension in the Mommy War: Our private judgments are so severe that it is impossible to look one another in the eye without seeing our own inadequacies. On and on the intimidation goes. Working moms view stay-at-home moms as idle and silly, traitors in the battle to encourage men to assume more responsibility at home. Stay-at-home moms view working moms as selfish and greedy, cheating their own children out of a strong maternal bond.

Instead of just acknowledging those judgments outright, we congratulate each other in patronizing ways. Working moms compliment stay-at-home moms for being better at the crucial (read: trivial) details—reading stories, tying shoelaces, playing in the sandbox. Stay-at-home moms praise working moms on their career successes (read: selfishness). As one mom told me, “I may have my kids together, but you’ve got yourself together.”

The battles are fought on common ground—schools, Little League fields, dance class, any place where women and children congregate. Robin Bowman, who owns a marketing business in San Antonio, recalls taking time off from work to attend an organizational meeting for Girl Scout troop leaders. The meeting was scheduled for nine on a weekday morning, an inconvenient time for Robin. But Robin has a seven-year-old daughter who is a Brownie and thought the meeting was important enough to rearrange her work schedule. Still, she was tense about the time and felt her anger build as the Girl Scout officials and stay-at-home moms socialized for twenty minutes before starting the meeting. Ten minutes after the meeting finally started, they broke for refreshments. “By the time I got out of there, I had decided not to go to any more of those meetings,” said Robin. “They’re too time-consuming, and not enough gets done.” Stay-at-home mothers can be equally strident. Beverly Childress Harkey, a 36-year-old Austin mother with two children, often wears her “Every Mother Is a Working Mother” T-shirt when it’s her turn to drive the car pool. She bought the T-shirt from the Austin Preschool Mothers Club, which also sells children’s shirts that say: “I’m One of My Mom’s Full Time Jobs.” The choice of words betrays the defensiveness even the most militant stay-at-home moms feel. Raising children, Harkey points out, is far more than a job, and yet in today’s world it’s hard to be taken seriously by other women if one doesn’t use the language of the workplace.

Nevertheless, mothers like Harkey are certain of their priorities. “If I can raise a decent child,” Harkey says, “then I’ve accomplished something more valuable than mothers who bring home a paycheck have.” That’s one more example of the polarized nature of the Mommy War—that bringing home a paycheck and raising decent children are thought of as mutually exclusive goals.

No one ever asked my mother the What do you do? question. The question had not yet been formed by the culture. Even though my mother was a schoolteacher, no one seemed to care much about her job; what mattered was that she was the mother of two children. I remember the day I realized my mother’s work was important to her. I was about eight years old and tagging along with Mom to a parent-teacher meeting. A father of one of the kids in my mother’s class approached and thanked her for something special she had done for his son. A look of satisfaction crossed her face. The satisfaction had nothing to do with me or my brother or my father. It was hers alone.

From then on, I knew my mother worked not only because we relied upon her income but also because she was secretly happy doing it. That was when I knew the world of work was for me. I was shaped more by what my mother left unsaid than by anything she said aloud. The source of my own ambition is my mother’s secret pride in her accomplishments.

My mother had married at seventeen—right out of high school. When I was the age of my four-year-old daughter, my mom was still in college. She went to classes at night, when my father could stay home with my brother and me. My earliest memories of her are of the two of us sitting at the kitchen table—I was reading children’s books and tracing the letters of the alphabet and my mother was studying for exams. She wanted college to be easier for me, and it was.

About the time I was in second grade, my mom launched her teaching career. It helped that she, my brother, and I had compatible hours. We all got up in the morning, went off to school, and came home together in the afternoon. If Mother had to stay late, my father picked us up and took care of us. Work was central to both my parents’ lives. The message from both of them, but especially my mother, was clear: Go farther than I did. One reason the Mommy War has such a feverish pitch is that we’re all carrying our mothers’ dreams.

I’ll come clean. As I grew up, I formed a prejudice against stay-at-home mothers. The way my mother ran her life and our house framed my thinking about what is important and what isn’t. I admired her for being busy, productive, and connected to the outside world, and I resolved to be that way myself. Homework was important; housework wasn’t.

Even if my family didn’t need my salary, I would still work. By the time my daughter, Maury, was born, I was 35—too old to stop thinking of myself in terms of work. I want for Maury the same thing my mother wanted for me: to find something to do with her life that she loves, in addition to her children. The stay-at-home moms I have talked to say they want unlimited choices for their daughters, but I wonder if our daughters will know how to juggle careers and families unless they see us doing it. The difference between my generation of mothers and the others is that we have fewer assumptions and more options. But the mommies of my generation aren’t certain of our choices; instead of defining ourselves as we see fit, we cling to both old and new roles. That’s what the Mommy War is all about.

Larkspur Elementary School sits on an open field in a suburban neighborhood in north San Antonio, its flat face gleaming against the great spring sky. For the most part, stay-at-home moms run the school—at least in terms of dominating parental involvement—and it’s in the interest of working moms to let them do so.

Nancy Bryant, a stay-at-home mom, is the president of the Larkspur Parent-Teacher Association. Therefore, she is a de facto political boss around school. At 42, Nancy has the life she always dreamed of: a comfortable two-story house in affluent Churchill Estates; a husband who earns a stable living selling insurance; a fifteen-year-old stepson, Michael, and a nine-year-old daughter, Sarah. Before Sarah was born, Nancy worked as a schoolteacher. “I always wanted to be a mommy,” says Nancy. “Now that I am, I’m devoting all my time and energy to these kids. They come first.” Other parents at Larkspur benefit from Nancy’s devotion, whether they know it or not. Much of what the PTA does is important. It organizes volunteers to run computer labs and career days and raises money through the school carnival for field trips and for supplemental art programs.

Of the 35 mothers on Larkspur’s PTA board, only 3 are full-time working moms. Subconsciously, the stay-at-home moms have cut everybody else out. Even if more working moms wanted to be active in leadership positions, it would be logistically dicey, since board meetings are on Thursday mornings. Nancy defends the morning meetings, saying it’s the stay-at-home moms who have the time to volunteer at the school. “Why should I inconvenience myself by giving up an evening at home with my kids when most of the working parents won’t show up anyway?” says Nancy.

The Mommy War is so highly charged that even casual exchanges can be explosive. For instance, the PTA recently sponsored a lecture by a psychologist on the developmental stages of children. To lure the working parents into attending, the lecture preceded song presentations by the children. Even so, Nancy overheard one working mom complain about having to sit through the lecture. Perhaps the working mother knew the material in the lecture. Perhaps she was feeling cranky. Maybe she was just an unpleasant person. Nonetheless, such remarks take on exaggerated importance. “People like that really do irritate me,” Nancy says.

The children of moms who volunteer at the school enjoy a certain patronage that is simply out of the reach of the children of working moms. Schools are like all other institutions—the squeaky wheels get greased. Strictly speaking, parents aren’t allowed to choose their child’s teacher at Larkspur. But one involved PTA mother got precisely the teacher she wanted for her child without even requesting her. In fact, all Larkspur third-graders with parents who are PTA board members landed in the class taught by the woman who is uniformly regarded as the best third-grade teacher at the school.

While roaming the halls of Larkspur, Nancy and I came across a fourth-grade teacher who was preparing new bulletin boards. We stopped to chat. I asked the teacher if she saw a difference in her class between the children of working moms and the children of stay-at-home moms. “Oh, yes,” she said, without hesitation. “The kids with moms who work come to school without their hair combed, without their homework done, and looking tired.” The stereotype left me speechless. I suddenly panicked. What if I had sent Maury off to school without combing her hair?

For the next couple of weeks the morning tension level in our house soared as I relentlessly nagged Maury about her hair. Finally one morning I walked into Maury’s classroom and looked closely at the other children. I couldn’t tell the children of stay-at-home moms apart from the children of working moms. All the children’s hair looked about the same. My daughter and I had become war casualties. While I was privately critical of favoritism at Larkspur, my entire human worth and dignity as a mother was caught up in Maury’s hair. The stay-at-home moms and I were doing exactly the same thing: holding out our children as proof that we have made the right choices about motherhood.

Charlene Weirich, a 37-year-old single mom who has a fourth-grader at Larkspur, is not free of rationalization either. Charlene tells herself that the long hours she puts in as a teacher at another school won’t hurt her own children. She has tried both ways—working and staying at home—and feels that working is better for her and the kids. When her son, Jeffrey, was a baby, Charlene stayed home but quickly grew restless. “I figured there had to be more to life than baking cookies and making mud pies,” she said. To stay-at-home moms, of course, cookies and mud pies are not what motherhood is all about. Rather, it’s about establishing an unshakable bond in the child’s early years so the child freely forms natural and intimate ties with others. Instead, Charlene believes that staying at home with Jeffrey was an obstacle to his independence. Her twenty-month-old daughter, Megan, now stays with a baby-sitter during the day. “I sometimes feel I’m missing out with Megan, but that has to do with me, not her,” Charlene says.

Aside from baking cookies for the school carnival and taking time off from work to attend teacher conferences, Charlene has little contact with Larkspur. She doesn’t go to PTA meetings and doesn’t drive on field trips. Were it not for mothers like Nancy, Charlene’s son wouldn’t go on such trips. She realizes other stay-at-home moms judge her harshly, but frankly, she doesn’t have the time or the energy to worry about it. Recently she was asked to work in a booth at the carnival, but she begged off—unwittingly placing herself on the front lines of the Mommy War. “I would have to hire a baby-sitter for two hours to work in that booth, and I’d rather spend that time with my own kids,” she says.

We gathered on the ranch porch, all fourteen of us, and sat in rocking chairs under a raftered ceiling. For two years, ever since we first gathered for a potluck dinner and baby shower, this group of women had been meeting every month, talking about any subject any one of us felt strongly about. Most of what I know about the mechanics of mothering—what car seats are the best, how to throw birthday parties, where to find good bargains on children’s clothes—I have learned from this group of women. I had come to think of us as a modern version of a quilting bee, without the sewing. One subject we had never talked about—until now—was our difference as mothers.

That afternoon we talked for hours. The stay-at-home moms had their say, as did the part-time and full-time workers. We were horrified at our own judgments of one another and at how quickly our voices became loud and angry. But we kept talking, and the battle lines blurred. The stay-at-home moms said they felt just as pressed for time as we did. Their days were filled with kids, meetings, doctor’s appointments, and the tyranny of the house. The working moms revealed that work was not a bed of roses and that there were often afternoons when we longed to escape to the sandbox with our children.

Each side discussed uneasiness about the fact that no one asked their husbands to choose between jobs and children. I remembered the day last year when Maury broke out with chicken pox while at school. I happened to be in Dallas that day on business, several hundred miles away, but a school official managed to track me down. While I sat in a Dallas law office, talking on the phone about Maury’s symptoms, I felt both helplessness and exasperation. Why hadn’t anybody thought to call my husband, who was only ten minutes from the school?

One reason there is a Mommy War is that mommies would rather fight one another than demand that men change. Those of us who are working mothers acknowledge that while we demand equality around the house, we often undermine it for fear of losing the last vestiges of domestic power. I often set up my husband, Clint, to fail by asking him to do some chore—like bathing the children—and then criticizing him for not doing it the way I would have done it. It is a struggle to keep from showing him I can do it better. The stay-at-home moms voiced their own secret fear: their husbands’ 25-year-old assistants. A failed marriage is emotionally traumatic for any woman, but at least a working mom is at an advantage when it comes to rebuilding her financial life.

The only thing we agreed on that afternoon was that all of us were trying too hard and that there was still refuge to be found in warm chocolate-chip cookies and cold white wine. For me, the critical moment came during a confrontation with Jill, a former emergency-room nurse who now stays at home with her two daughters. For most of the conversation, Jill had remained quiet. She had her hands full with her colicky newborn. But, during a group pause, she stood up, placed her child on her hip, and started to sway. Her voice was hushed; when she started to speak, her lips trembled. She was both angry and sad, and it was impossible to say which feeling was strongest. Looking straight at me, Jill said, “I’d never say this out loud, but I really do look at working moms and say to myself, ‘They shouldn’t be doing that. Their children will suffer.’”

At that moment, my infant son let out a howl. We paused to quiet the children, but I couldn’t let Jill’s comment pass. I was too angry. Jill wasn’t some stranger in the grocery store. She was my friend. “I wouldn’t ordinarily say this out loud either,” I told Jill, ashamed of the unpleasant hiss in my voice, “but stay-at-home moms really infuriate me. Why can’t they just be happy with their choice and leave the rest of us alone?”

After we’d said the worst, we sat in uncomfortable silence. I remembered something my friend Jane, a stay-at-home mom, had said earlier in the conversation. “Sometimes I think we are a generation cursed by choices,” she had said. “I feel resentful because my mother was able to be happy with her choices, without having to justify them.” Whether or not our mothers were happy is not the point. The point is whether our generation—with so many choices to justify—can make the choices that fulfill us and those we love. For that, we need more support than ever. At a time when women must define their own place, lest we once again be defined by men, no one can afford the shrill and easy judgments of the Mommy War.

After reconsidering what I said in anger to Jill, I decided that the person I was really talking to was myself. The only way out of the Mommy War is to go AWOL. For better or worse, I have made my choice and might as well stop justifying it. The final proof of who is a good mother and who is a bad mother is not whether they work or stay at home but whether they can extend themselves in love to their children.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- San Antonio