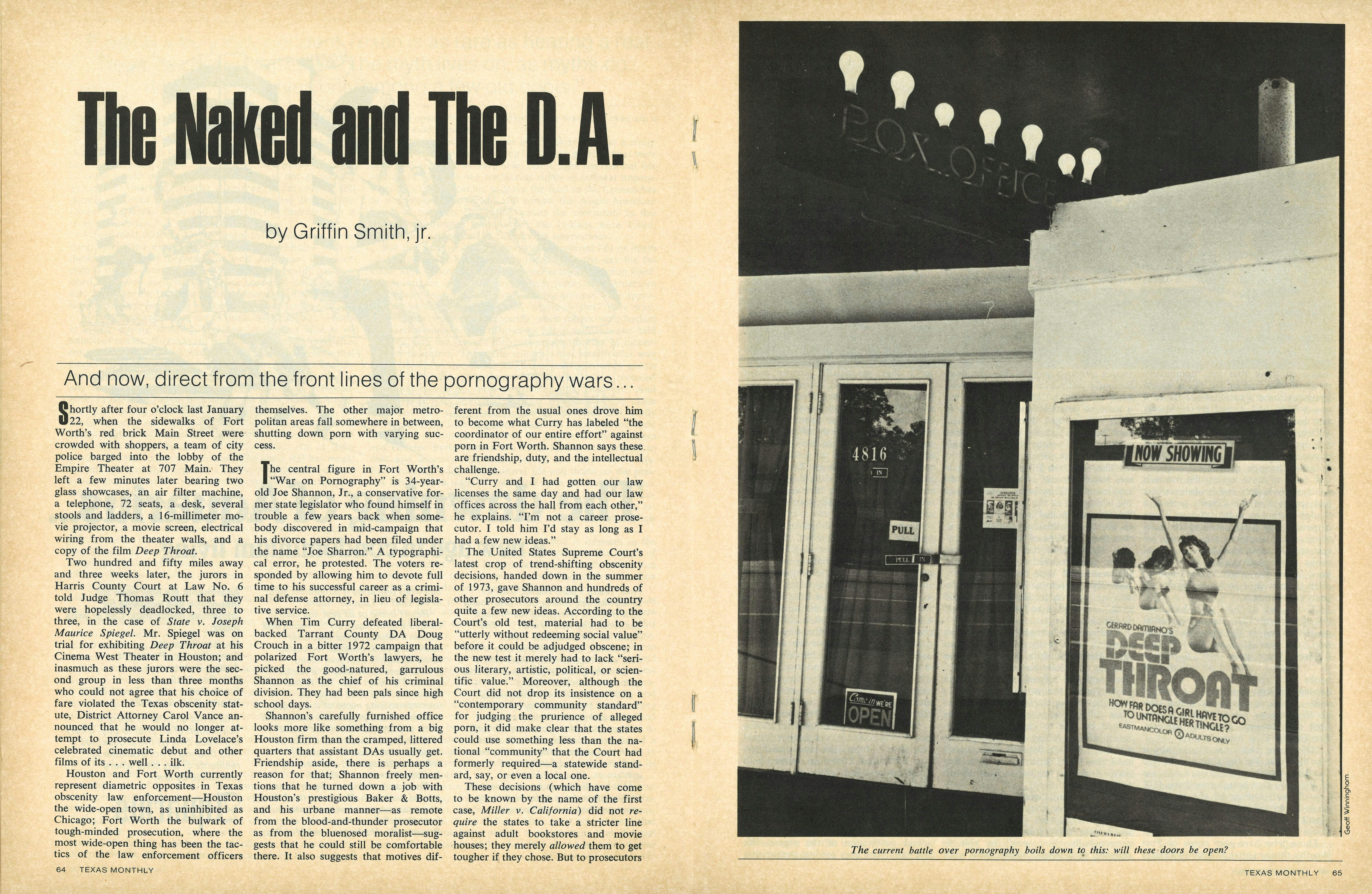

Shortly after four o’clock last January 22, when the sidewalks of Fort Worth’s red brick Main Street were crowded with shoppers, a team of city police barged into the lobby of the Empire Theater at 707 Main. They left a few minutes later bearing two glass showcases, an air filter machine, a telephone, 72 seats, a desk, several stools and ladders, a 16-millimeter movie projector, a movie screen, electrical wiring from the theater walls, and a copy of the film Deep Throat.

Two hundred and fifty miles away and three weeks later, the jurors in Harris County Court at Law No. 6 told Judge Thomas Routt that they were hopelessly deadlocked, three to three, in the case of State v. Joseph Maurice Spiegel. Mr. Spiegel was on trial for exhibiting Deep Throat at his Cinema West Theater in Houston; and inasmuch as these jurors were the second group in less than three months who could not agree that his choice of fare violated the Texas obscenity statute, District Attorney Carol Vance announced that he would no longer attempt to prosecute Linda Lovelace’s celebrated cinematic debut and other films of its… well… ilk.

Houston and Fort Worth currently represent diametric opposites in Texas obscenity law enforcement—Houston the wide-open town, as uninhibited as Chicago; Fort Worth the bulwark of tough-minded prosecution, where the most wide-open thing has been the tactics of the law enforcement officers themselves. The other major metropolitan areas fall somewhere in between, shutting down porn with varying success.

The central figure in Fort Worth’s “War on Pornography” is 34-year-old Joe Shannon, Jr., a conservative former state legislator who found himself in trouble a few years back when somebody discovered in mid-campaign that his divorce papers had been filed under the name “Joe Sharron.” A typographical error, he protested. The voters responded by allowing him to devote full time to his successful career as a criminal defense attorney, in lieu of legislative service.

When Tim Curry defeated liberal-backed Tarrant County DA Doug Crouch in a bitter 1972 campaign that polarized Fort Worth’s lawyers, he picked the good-natured, garrulous Shannon as the chief of his criminal division. They had been pals since high school days.

Shannon’s carefully furnished office looks more like something from a big Houston firm than the cramped, littered quarters that assistant DAs usually get. Friendship aside, there is perhaps a reason for that; Shannon freely mentions that, he turned down a job with Houston’s prestigious Baker & Botts, and his urbane manner—as remote from the blood-and-thunder prosecutor as from the bluenosed moralist—suggests that he could still be comfortable there. It also suggests that motives different from the usual ones drove him to become what Curry has labeled “the coordinator of our entire effort” against porn in Fort Worth. Shannon says these are friendship, ditty, and the intellectual challenge.

“Curry and I had gotten our law licenses the same day and had our law offices across the hall from each other,” he explains. “I’m not a career prosecutor. I told him I’d stay as long as I had a few new ideas.”

The United States Supreme Court’s latest crop of trend-shifting obscenity decisions, handed down in the summer of 1973, gave Shannon and hundreds of other prosecutors around the country quite a few new ideas. According to the Court’s old test, material had to be “utterly without redeeming social value” before it could be adjudged obscene; in the new test it merely had to lack “serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value.” Moreover, although the Court did not drop its insistence on a “contemporary community standard” for judging the prurience of alleged porn, it did make clear that the states could use something less than the national “community” that the Court had formerly required—a statewide standard, say, or even a local one.

These decisions (which have come to be known by the name of the first case, Miller v. California) did not require the states to take a stricter line against adult bookstores and movie houses; they merely allowed them to get tougher if they chose. But to prosecutors everywhere, the big news was the chance to drive home a “local” community standard; with dens of iniquity like Times Square and San Francisco’s Broadway no longer in the picture, a jury right there in River City could be free to use River City’s community standard. Operators of XXX-rated movie houses shuddered, DAs rejoiced, and a spate of arrests followed.

Texas was no exception, despite the fact that the Legislature had thoughtfully copied the old Supreme Court test into the state obscenity law, and Texas prosecutors were therefore still required to prove everything they had had to prove before Miller. Paradoxically, it was Miller’s invitation to look at porn in light of a local community standard that ignited the prosecutorial bonfires in Fort Worth, even though there is every reason to think that the “community standard” required by the Texas statute continues to be a national one, since it was written and passed by legislators who had never heard of Miller.

Debatable legal niceties like that were not uppermost in the minds of Texas prosecutors, however. After the Miller decision Shannon assembled a special task force to move against the fourteen adult movie houses and bookstores that had sprouted in the Court’s protective shadow during more lenient days. These emporia, like their counterparts elsewhere, were engaged in a rapidly accelerating contest to show movies and books more explicit than their neighbors’ down the street. Shannon went after them with a force consisting entirely of volunteers.

“Every one of these guys had been out of law school less than a year when we got started on this porno thing,” he says. “It was kind of like Nader’s Raiders. These guys, boy! Enthusiastic… eager… they’d get into the law books and root that stuff out. We briefed obscenity laws to a fare-thee-well… We’ve tried to do it real lawyer-like because you’re walking a very tight rope between obscenity prosecution and the First Amendment.

“Of course, that’s one reason why it fascinates me. I’m the kind of a lawyer that likes mental gymnastics. I was one of the guys that hung around the [UT Law School] lounge all the time and made up hypotheticals, you know… That’s the kind of law I like. I like doing things nobody’s ever done before.”

Those who have seen some of Fort Worth’s theaters after Shannon’s Raiders have finished with them are the first to agree that he does things nobody has ever done before—at least not in Texas within recent memory. In their opening salvo last January 15, sixty policemen, prosecutors, and support personnel made simultaneous mass raids on nine separate porno houses. In these and subsequent raids throughout 1974, authorities have seized 450 reels of 16-millimeter film, hundreds of magazines, and a variety of other paraphernalia ranging from plastic battery-operated vibrators of the sort available in the corner drug store, to lifelike rubber dildos, French ticklers, jars of Orgy Butter, and Vice Spice. So far they have left the Wesson Oil at Safeway alone.

Defense attorneys for the adult movie houses get squinty-eyed and hard-jawed when they talk about Shannon’s tactics, although many of them get along famously with him as an individual. Mike Aranson, a Dallas lawyer who has a national practice (and reputation) in porn cases—or “First Amendment Law,” as the defense attorneys prefer to describe it—came up against Shannon early in the game.

“They took the Ellwest Stereo Theater, which is one of my clients,” he says evenly. “They went in and ripped the wiring out of the walls—went up in the attic and pulled it out. They kicked in the air-conditioning compressors so that they could be of no value to anyone. They ripped the plywood booths down. They knocked the coin boxes off the walls and kept the money. They took the projectors. They literally destroyed the theater. Destroyed it.” His even tone is gone and there are sparks in his eyes.

Pushing 40, Aranson seems to relish breaking the somber lawyer stereotype. His blond hair, graying, recedes in front and descends in back; to legal documents he affixes a signature that looks for all the world like a potato wearing a string tie. He can talk for an hour about why consenting adults should be able to view whatever they want, almost lulling the listener into forgetting that the Supreme Court hasn’t read the First Amendment quite that way. And the tactics in Fort Worth make him mad.

“It’s a non-judicial approach,” he says. “Whatever they feel like doing, that’s what they do. They said if you don’t stop, we’re going to destroy you economically. You won’t be able to operate, so it doesn’t matter what your rights are.

“For example, in the case that I tried, they had lined up all of the patrons in the theater and made them give their identification on the way out the door. They did it solely for one purpose: to make damn sure that the people of Fort Worth knew that if they went to a porno house they were running the risk of ending up with their name on a list. I mean, they don’t do that when you go to see Mary Poppins.” Attending an obscene movie, of course, is not a crime.

Shannon, on the other hand, prefers to talk less about tactics and more about the fact—and it is a fact—that adult movies and merchandise have increasingly shed their inhibitions and become what jurists delicately call “explicit.” Guarded by warning signs (“If the nude human body offends you, do not enter”) they graphically portray every form of heterosexual activity that sex pollsters have discovered one per cent or more of Americans enjoying, as well as a variety of other forms for more specialized tastes. In an effort to keep on the right side of the law, much of it has been dressed up as sex-instruction material or, like Deep Throat, supplied with a plot; but the days of prim manuals that refer to “the marital act” seem gone for good. Sex for the sake of sex is out front.

Shannon has moved against all three types of “adult” enterprises: the bookstores, which specialize in pulp novels costing two to four dollars and color magazines costing up to ten; the peep-shows like the Ellwest, which contain a dozen or more private curtained booths showing unadorned sex films on a two-foot square screen, usually on an endless loop costing the customer a quarter for each three or four minutes; and the full-fledged movie houses, which feature color-and-sound films with plot, dialogue, and an increasingly serious attempt at socio-sexual commentary—films like Behind the Green Door and The Devil in Miss Jones.

In each case, he has tried to draw a line dividing what he considers criminal “hardcore” from the look-the-other-way “softcore.” That done, heaven help the hardcore. But where to draw the line?

“Our biggest problem,” he says, “was to make sure we had some guidelines the average cop could understand. Well, the only line of demarcation was the actual penetration of the organs. We felt like if you ever got into prosecuting simulated sexual conduct there was no legitimate place to draw the line. The next step over from actual penetration was two nude bodies writhing around with one another, where although you don’t actually see the penetration of the organs you see the organs. The next step from that is where you have the writhing around but you don’t actually see the organs. The next step after that is, you have the writhing around but it’s under a bedsheet, and then the next step after that is, you hear the writhing around off-camera. There is no logical place to draw the line once you get past penetration. So that’s the reason why we have focused strictly on what we call the bull’s-eye… That’s been the whole thrust of our approach.”

Shannon defends his flamboyant tactics, even though he stopped using most of them after Federal District Judge Eldon Mahon took him aside in chambers last February and suggested he might be carrying things a little far. On seizing the glass showcases from theater lobbies: “They were being used in the commission of the offense; they had goods for sale in them.”

On ripping out the wiring: “It’s an implement of the crime.”

On removing the 72 seats: “We took them to get semen samples. You’ve got to show that the matter appeals to a prurient interest, and if you can show that the audience is sitting there masturbating, that’s certainly some evidence of prurient interest.” Beside, he says, “We didn’t take all the seats. [The owners] are hollering, ‘aw, they took our seats out,’ but we didn’t take all the seats. We just took some of them.”

On checking the patrons’ IDs: “We were concerned that down the road there’d be some claims of somebody being roughed up. We wanted to have a complete record of everyone who was there at the time. The lists don’t ever go anywhere; they just stay in our files.”

What is behind Fort Worth’s “War”? Outright prudery seems to have nothing to do with it. Shannon is careful to dissociate himself from the ardent moralists in town—he dismisses the “fringe element, people who think anything other than a G-rated movie is just bad. We’re not interested in dealing with puritanical nuts, and there’s a lot of them running around.” He is willing to overlook anything he considers softcore—“even though I think simulated sexual conduct is clearly prosecutable… we have not chosen to get into that.” His strikingly beautiful wife Carol teaches Advanced Belly-Dancing at Tarrant County Junior College, a sure sign the Shannon family is not a bunch of puritans.

One thing that can be said with certainty about Fort Worth’s War is that it coincided neatly with DA Curry’s hot re-election campaign against political newcomer Joe Brent Johnson. The January raids were carried out downtown in the full glare of television cameras, proving that Something Was Being Done, and by the time Judge Mahon quietly and informally put a stop to the search-and-destroy missions, Curry was on his way to a comfortable two-to-one victory in the May Democratic primary. Curry’s response to criticism of the raids showed what was uppermost in his mind. “If they don’t like for us to prosecute pornography this way,” he said, “they can vote me out of office.”

After ten months, Shannon had collected a total of twelve convictions, some by guilty pleas and others by jury verdicts. But no one has yet gone to jail or actually paid a fine; every case is still on appeal. Meanwhile Fort Worth’s surviving adult bookstores and movie houses are showing mostly softcore material by his definition, although the Empire and the Cinema X still offer some hardcore. At the Empire, unlike virtually every other adult shop in Texas, the hardcore magazines remain unsealed on open shelves. Well, not quite open—it’s a dollar an hour to browse.

Every type of adult mart in Houston, by contrast, is filled with hardcore material. Peep shows in particular are prospering—whole rooms lit by black lights, posters aglow, with hand-lettered signs describing in detail the content of the films available to anyone over eighteen who has the inclination to shell out a quarter for a few perfunctory minutes of voyeurism. For those who regard explicit on-screen sex as the work of the devil, Houston is both the Sodom and Gomorrah of Texas.

The state’s largest city also neatly illustrates how dubious anything called a “community standard” really is—even a local one, not to mention national. The Supreme Court’s Miller decision confidently envisions lay jurors who can “draw on the standards of their community” to decide what appeals to the prurient interests of their neighbors, but the actual attempt to distill into a single rule the feelings of 1.4 million Houstonians on a subject as personal as sex is a dizzying, perhaps even an impossible, task. Conceivably there were recognizable community standards 75 years ago, but can there be one today in a city of any size?

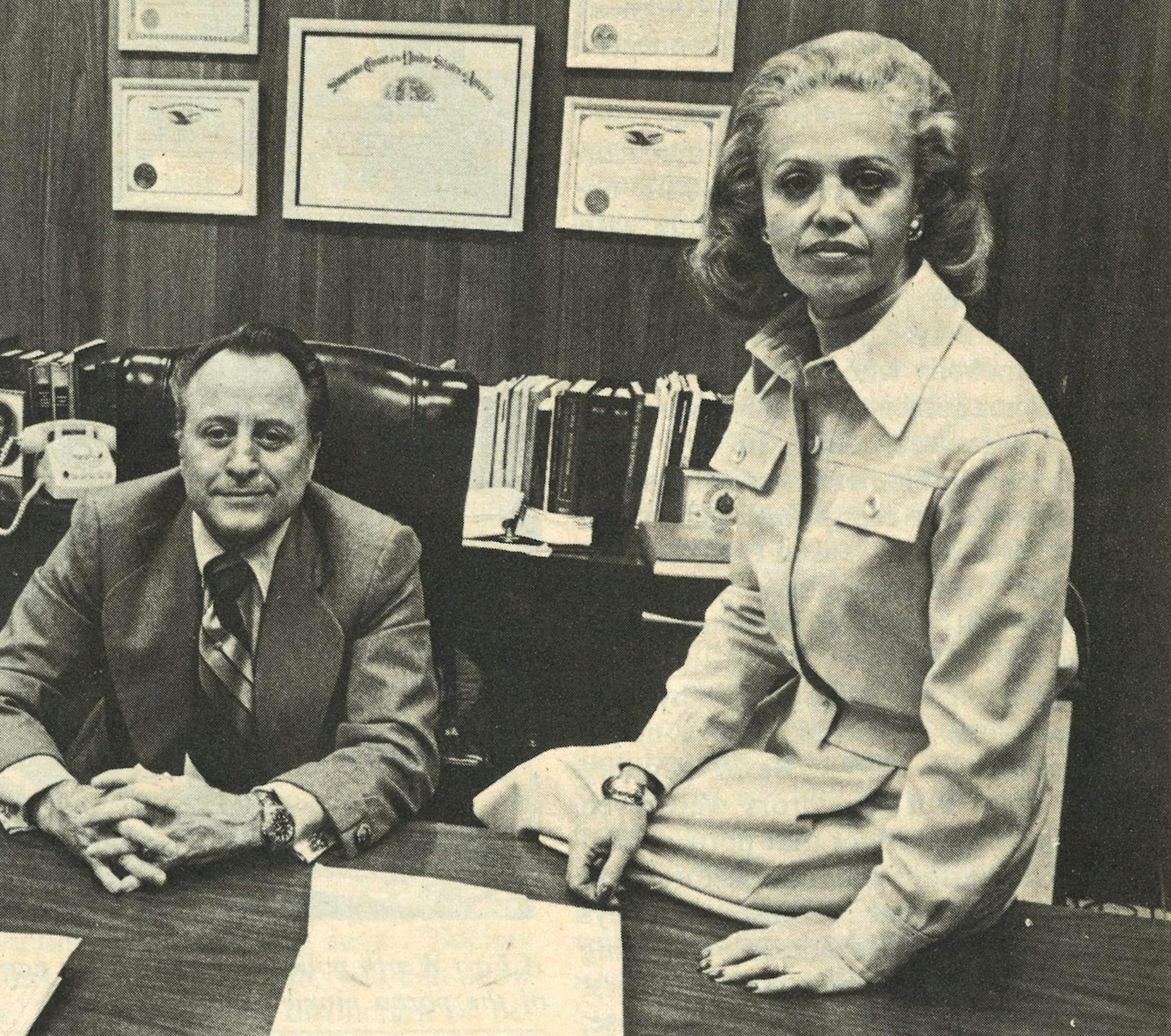

Nevertheless, that is the way the game is being played these days. If there is any such thing as a “community standard,” Houston’s is the only one in Texas that may be firmly tolerant of hardcore pornography for consenting adults. Clyde Woody, 53, who successfully defended Joe Spiegel twice against the obscenity charges on Deep Throat, thinks he knows why.

“The community standard is molded, it is made, it is the product of the individuals who are prosecuting and defending obscenity cases,” he declares, his own hands molding the words as he swivels at his broad desk in Houston’s First Savings Building. He is glad that Carol Vance chose to do battle over Deep Throat because he strongly suspects it was a battle the prosecution was foreordained to lose. Unlike Dallas District Attorney Henry Wade, who started with the cheapest, shoddiest, no-soundtrack porn movies he could find and orchestrated his convictions to a crescendo with Deep Throat, Vance tackled one of the biggest-grossing movies of 1973, an authentic bit of contemporary pop culture that had already shown in Houston the year before and was rapidly reaching the status of a nationwide joke. Sexually explicit it surely was, but not like some other things Vance could have picked.

“There are a lot of cases you could get a Houston jury to convict just like that,” says Woody, snapping his fingers with the finality of a cell lock clicking shut. “As an example, well, the animal acts. Why, a jury would convict in a minute. All you have to do is show it and—snap—“they’d give you the Max. These are cases that are indefensible. No way anyone could defend them. They are, under any sense of the word obscene.”

Woody’s own skillful performance in the Deep Throat trials is the best evidence to support his theory about the way a “community standard” is really shaped. He and his partner, Marian Rosen, drenched the jury with facts, figures, and testimony about the prurient and not-so-prurient tastes of their fellow Houstonians. They summoned psychologists, priests, chemical engineers, housewives, and black Baptist preachers to testify on the harmlessness of Linda Lovelace’s engrossing talent. Persuasively ordinary Houstonians took the witness stand to affirm that they enjoyed seeing porn. Woody and Rosen unreeled statistics purporting to show that the equivalent of 30 per cent of Harris County’s population had attended an adult movie house in the past three years.

“You have to develop a rapport with the jury in the most intimate personal aspects of their lives,” Woody says. “When you start exposing sexually liberated ideals you’re creating a problem for the individual within himself; it makes him re-evaluate his own principles. The first thing you have to do is get him talking about it”—Woody uses the best-selling Joy of Sex to break the ice and then moves to typical hardcore magazines—“and then you absolutely have to make a deal with him: that if he finds the community standard to be different from his own, he will accept that of the community under his sworn oath as a juror. He is going to have to abandon his own standards of morality.”

Rosen’s presence gave the defense one inestimable advantage; with a woman participating in the trial from start to finish, the whole proceeding never got entangled in the embarrassed unease that has turned so many obscenity cases into open-and-shut victories for the prosecution. Because the female jurors were more candid with her on voir dire, she feels “we were able to discuss sexually oriented matters in a different way.”

But the trial itself was not the only difference; law enforcement methods in Houston are comfortably removed from Fort Worth’s frenetic tempo. The Houston vice squad has carefully avoided the crowbar tactics that attracted such attention up north, and the DA’s office takes a rather more philosophical view of what the Bayou City’s residents are willing to accept.

For the Deep Throat trial Vance picked his former executive assistant, Mike Hinton, whose regular duties involve such things as organized crime, auto theft, narcotics, and extortion cases. Hinton, a friend and contemporary of Shannon’s, is both more moralistic and more forbearing than his fellow prosecutor.

On the one hand he believes the criminal law should be used to enforce morality. “I do not pretend to be an expert in the obscenity field,” he says. “But I do think there is a line to be drawn somewhere… I feel that the moral atmosphere of any society is the ultimate regulator of all conduct… The role of law in this and some other areas, like gambling, is to make a moral statement about the kind of society we wish to live in. It concerns the very quality of life and the tone of that society.”

On the other hand, Hinton views the hung jury in Deep Throat with a kind of detached resignation. He seems halfway glad that Vance’s decision not to prosecute any porn films with a pretense to artistic merit has relieved him of the responsibility to talk a jury into making a moral statement about the kind of society they wish to live in. “We’ve received plenty of criticism,” he says, “like ‘what are you doing prosecuting obscenity that people willingly pay money to go see when there are all these murderers running around?’ Well, there’s no question about the fact that we got lots of murder and lots of rape and robbery and I and my other 104 fellow lawyers in this office have got other things to do besides worry about Deep Throat. But you’ve got to realize that there’s another contingent of people in this society that think this is a good law and a proper law and it ought to be enforced to the hilt. Some of those people, a very few, of them, think we don’t have anything else to do but that. So where are you?

“You get to a point where you think, shouldn’t there be a line drawn someplace? And apparently, if the jurors are representative of the people in this area, they have said, ‘Well, we can’t make up our minds on that. There’s a line someplace in it, a zigzaggy line through it.’ But after that second hung jury, I don’t know where that line is.”

Intractable and subjective, the issue of community standards has stalled Houston prosecutions. On a few kinds of cases—those that deal with bodily elimination “or anything involving a child or bestiality,” Hinton says—Vance’s office gets swift pleas of guilty. But otherwise, he adds, “People in Houston just aren’t willing to start setting standards for everyone else… They are consciously aware that there are other sorts of folks with different strokes.”

Among the remaining major Texas cities, San Antonio’s porn crackdown runs a surprising second to Fort Worth’s. Its country-born DA, Ted Butler, suddenly waxed indignant at the increasingly raunchy screen offerings in his adopted city a few days after Miller was handed down. Instead of the wreckage visited on the porn merchants in Tarrant County, though, Bexar County has witnessed a tough, theatrical, and undeniably inventive series of legal maneuvers.

John Quinlan III, the capable head of Butler’s “Special Crime” section (which attends to such diverse matters as white-collar crime, ecology, and the massive Coastal States Gas investigation), was chosen to lead the assault on pornography. A visit to some of the theaters convinced him that even if different folks did have different strokes, they ought to be doing their stroking somewhere outside of Bexar County.

“I guess I hadn’t been to one of those porno places since 1968 or 1969,” says the mustachioed, cigar-smoking Quinlan, who carries a beeper and looks like Oliver Hardy impersonating Broderick Crawford. “These guys came back to me and they were shocked, you know, wild-eyed, and they said, ‘You just don’t know what’s going on in those places.’ And I said, ‘Well, they’re showing a dirty movie—probably a bunch of screwin’ and stuff going on.’ And they said, ‘No; that’s the least of what’s going on in there. You can’t believe what you’ll find in those peep-show machines.’”

The content is not the only thing that shocked Quinlan. “You know, they’re covered with sperm. All over the walls, the floor. I didn’t know sperm was luminous—I guess that’s the right word—but if you turn on ultraviolet lights, sperm glows. We went into one theater with a light from the crime lab and the whole place went zong!” He gestures with an expansive, sunrise motion. “In fact, we found a sperm mark eight feet six inches up the wall, which I thought was a record of some sort.”

Defense attorneys heatedly deny that things are anywhere near as bad as Quintan pictures them, although they admit that an occasional patron does bring an overcoat for a reason. If nobody but dirty old men bought tickets, the adult movie business would not be as spectacularly lucrative as the prosecutors themselves insist it is.

The profits, they say, often go into the coffers of organized crime. That is a difficult claim to evaluate. The wholesale porn market does appear highly centralized, and not even the defense attorneys pretend there are any “Ma and Pa” retail dirty bookstores around. With them it seems to be a rather touchy subject. Says Mike Aranson: “Well, uh, I wouldn’t be in a position to comment that any of my clients are not connected or are connected with something which might be called organized crime… But there have been no cases made on anyone notoriously connected with organized crime in this state dealing with the distribution or exhibition of pornographic matter. I know my people. While they may know somebody who knows somebody who knows somebody, they are not subject to the bureaucratic lines of organized crime. In five years where’s one indictment, one charge? If law enforcement really had something, wouldn’t it stand to reason they’d rather have Mr. Gambino, say, than Joe Schmuck out here who’s running a projector?”

Distribution of pornography by “the national crime syndicate” was a major concern of the 1973 Bexar County Grand Jury. But the jurors were even more upset by the fact that porn existed at all. The various adult bookstores and movie houses that defense attorneys consider legitimate businesses, operating under the protection of the First Amendment until proven otherwise, were regarded by the Grand Jury as an attack on “the very heart and fiber of traditional American values of home, religion, and country,” fostering health hazards, fire hazards, prostitution, and on-screen depiction of “every form of moral depravity the human mind is capable of except cannibalism.” (A dubiously authentic San Antonio group calling itself Students To Overthrow Pornography has gone even farther, sending the DA an unsigned note threatening to bomb all movie houses showing PG and R rated films and any TV station that carries The Summer of ’42. Quinlan was not treating it as a hoax.)

To discuss pornography with the prosecution and then with the defense is to hear descriptions of two different worlds—one the story of depraved patrons (“the dregs of San Antonio society,” said the Grand Jury) and the other, the story of a (strangely shadowy) entrepreneur’s valiant fight for the freedom of the mind against censors who, if they can ever manage to forbid technicolor orgasms, will surely next attempt to scissor the Song of Solomon out of the Bible. Neither view has much connection with reality.

The real issues are two: first, the extent to which the criminal law should be used “to make a moral statement about the kind of society we wish to live in,” as Houston’s Mike Hinton puts it. That is a decision which, for better or worse, the legislators and not the law enforcers have to make, within whatever space the Supreme Court leaves them. The second issue is the power of the state to harass and intimidate businessmen before they are convicted of breaking the law. That is a decision the law enforcers can make at will, and it is a subject about which the defense attorneys are understandably more articulate than the prosecutors and police.

Among the most articulate is Mack Ausburn, a youthful San Antonian who has defended the owners of several of the hardest-hit movie houses there. The DA’s 1973 anti-pornography campaign was supported by “huge amounts of police activity,” he recalls. “Theaters were being raided on a daily-type basis. Raid after raid after raid. Needless to say, the weak cannot survive that type of treatment because of loss of equipment, film, the tremendous bail bond expense, and the tremendous legal expenses in fighting this type of thing. So in that sense the District Attorney’s office was successful. Where there had been twelve or thirteen adult movie houses. In San Antonio, suddenly there were three or four. A huge number of cases were made. By the end of 1973 they had saved San Antonio from eternal damnation and made society safe for… for whoever they were making it safe for.”

The indignant Grand Jury returned some peculiar indictments against 34 individuals in November, 1973. Exhibition of obscene material is a misdemeanor in Texas. But the indictments were for “conspiracy” to exhibit obscene material, which until January 1, 1974, was a felony. San Antonio was not the only city to circumvent the plain meaning of the obscenity statute by turning misdemeanors into felonies this way, but the technique constitutes such transparent dirty pool that many scrupulous prosecutors would have none of it. Mike Hinton, for example, insisted on dropping the conspiracy charges against Joe Spiegel before agreeing to participate in Houston’s second Deep Throat trial, saying, “I don’t believe that [conspiracy] statute was ever constitutional, and I would not have had any part in a prosecution under it.”

Quinlan is an effective prosecutor, and there is nothing slipshod about the campaign he runs. “The activity here, in its formalism, assumes all of the procedural niceties you could possibly imagine,” Ausburn says. “The District Attorney’s office goes forth on its raids with the vice bureau armed with a little suitcase full of papers; they will just procedurally due-process the hell out of you.” From the defense standpoint, the problem is not with the procedure but with the enormous latitude the law gives to public officials to make life unbearable for those whose activities they deplore.

Every city seems to have a Deep Throat controversy, and Ausburn has been in the middle of San Antonio’s. Police seized copies of the film four times in less than two weeks last summer, a pattern Ausburn considers outrageous. “The way I read the cases,” he says, “if that’s the only print available, you have to let the defendant make a copy so he can continue to show it until there is a final judicial determination of obscenity; anything else is a prior restraint. These multiple seizures are in the category of dirty tricks. ‘We are gonna bust this sonofabitch, we’re gonna take his film and projector until we run him out of business’—that is the approach. That’s not legitimate law enforcement. That’s official lawlessness, lawlessness on the part of people who carry guns and badges and credentials.”

Whether Ausburn is right about the law will be decided by a three-judge federal court in Houston, where he has sought to enjoin the multiple seizures. He has also asked the same court to consider what he calls “this insane, absolutely insane, situation on bonds.” The Fiesta Theater operator, Richard Dexter, and three of his employees were hit with a total of $95,000 in bonds after the four seizures. Although showing Deep Throat could not “under any reasonable stretch of the imagination” amount to more than the misdemeanor offense of commercial obscenity (up to six months and a $1000 fine), Ausburn’s clients were charged with the felony offense of “possession of criminal instruments,” a category that covers anything “specially designed, made, or adapted” for the commission of an offense. Dexter’s movie projector was one of those, the prosecutors argued with a straight face, and the bond should be set accordingly. The legislators who had thought they were writing about burglar’s tools and safecracking equipment would probably disagree—as does Joe Shannon in Fort Worth, who scoffs at the idea that a movie projector can be “specially designed” to show only obscene movies. Most bonds in Fort Worth have been set at $500. Nevertheless, in San Antonio a potential misdemeanor was once again transformed into a felony by legal sleight-of-hand.

But the felony was promptly forgotten when Dexter came to trial. Colorful Assistant DA Keith Burris handled the case and expected a hung jury. The parade of expert witnesses called during the week-long trial by defense attorney Jerry Goldstein (who had replaced Ausburn) did not assuage his fears. To Burris’ surprise, however, the jurors took only 30 minutes to convict Dexter of the misdemeanor obscenity charge. The sentence: 90 days and $150. “You never can tell about a jury,” says Burris.

Despite (or perhaps because of) the prosecution’s imaginative legal tactics, most of San Antonio’s remaining pornography questions are tied up in the three-judge federal court.

Meanwhile, softcore material predominates there, particularly in bookstores which oddly enough never received much attention from Quinlan’s forces. The films that remain on view seem unlikely to titillate anyone’s prurient interest very seriously.

There is something doleful about softcore porn that has been left behind after the high tide of hardcore has receded, rather like watching a tame, tired Indian perform the War Dance for tourist dimes. The porno performers must devise ways to occupy themselves in the absence of delivering that which has been so lasciviously promised; and, as Joe Shannon has observed, they writhe. At best, they writhe. More often they fill tubs with steaming bubble baths or drift into fantasies of Arabian belly dances: anything to keep busy. In one typically tedious softcore San Antonio film, a naked couple lay side by side on their backs atop a king size bed and merrily bounced up and down in disconnected ecstasy; in another, the He brought the Her to joyous fulfillment by rubbing her left nipple with his nose. There is every reason to believe the traditional American values will be able to survive that.

In brief, these are the developments in several other major cities:

• Dallas: With a conviction rate of 98 per cent in all jury trials, and with a professed policy of seeking the maximum jail time and fine, without probation, for every obscenity defendant above the level of a “ticket-taker,” District Attorney Henry Wade’s office is a formidable adversary for adult bookstore and theater owners. Strangely, despite numerous convictions, Dallas remains second to Houston as the state’s most wide-open town.

Young assistant district attorney Jerry Banks has been influential in the campaign against pornography. “It’s not a victimless crime,” he says. “Society suffers if you say, ‘Yeah, you can show this.’” Dallas has the distinction of being the only metropolitan area to move against softcore material as well as hardcore. Much of the impetus has come from police vice squad leader Mel Southall, who is terribly interested in cleaning up smut and feels a sense of public mission about the whole thing. After Joe Shannon’s spectacular debut in Fort Worth, Southall’s men embarked on similar crowbar-and-hammer missions. More than a score of raids were conducted on six theaters before police chief Don Byrd decided to call a halt. A favorite tactic in Dallas is to shuffle the arrested projectionists from one place to another, one step ahead of their lawyers, apparently on the theory that if no one can find them long enough to post their bail, they certainly aren’t going to be operating any projectors.

• Austin: The most moralistic DA in the state is probably Travis County’s Bob Smith, the bete noir of venal legislators, college kids who sell pot, and purveyors of dirty books and movies. A deeply religious man, he has few compunctions about using the full muscle of his office to help, his fellow Austinites on the path to clean living. He gets away with it in the Capital City’s predominantly liberal, sophisticated climate because he avoids showmanship. He disposed of most of Austin’s rapidly proliferating adult marts in 1973 by a quiet show of strength that persuaded most of the operators to accept a permanent injunction against their activities in exchange for dropping charges.

As a result there was not much left for County Attorney Ned Granger to do after the new Penal Code erased the felony conspiracy device and left misdemeanor obscenity enforcement in his hands. Enter, then, the Austin police department vice squad, which took up where Smith left off. Ever since the penalty for marijuana possession had been dropped to a misdemeanor in August 1973, depriving officers of the “trophy” aura that surrounded these easy-to-make felony arrests, the vice squad faced the worst fate any bureaucracy can face: atrophy. Loss of personnel. Maybe even a salary cut. The squad recoiled from that awful possibility and pulled itself together for an assault on one of the few survivors of Smith’s purge, Roy Stambaugh of the Austin Book Mart.

In a little over two months last spring, Austin police seized 3242 books, 54 reels of film, and 11 projectors from Stambaugh’s business on East Sixth Street; for a while he was being raided every third day. The seizure of 500 books a week was fairly routine. At one point, State District Judge Tom Blackwell (Smith’s predecessor as DA) issued a permanent injunction against Stambaugh, prohibiting him from showing not only certain named books but also anything else that was “obscene”— thus forcing the store owner to figure out in advance what might strike Blackwell as obscene, risking jail on contempt of court charges if he guessed wrong. Blackwell’s broad order was tantamount to censorship before trial and the federal courts quickly disposed of it except as far as the named titles were concerned. There are now 44 obscenity cases pending against Stambaugh, whose beleaguered store is still open.

Blackwell also decided Deep Throat was obscene and issued a permanent injunction against showing it. When Granger then tried to prosecute the theater operators, however, the jury deadlocked four-to-one for acquittal. A second trial in November produced a four-to-two deadlock the other way. This leaves Austin in the peculiar position of having a “community standard” on Deep Throat set by a solitary middle-aged former DA.

Lately the mood in Austin seems to be leveling off. The police vice squad has shifted its sights to the gambling activities of what one officer called “the country club set.”

• Corpus Christi: Corpus is the quietest of the major cities, the only one where bookstore sales are strictly softcore, and the only one where no adult movie houses are operating.

The Corpus vice squad, which has been the main initiator of anti-obscenity activity in Nueces County, hit the Texas Cine Arts theater in 1973 for showing hardcore movies like The Godmother, Specimen Female, and Husbands, Lovers, and Other Strangers. The operators agreed to a permanent injunction closing their premises in exchange for the dropping of charges. Rudy Garza, a general practitioner who spends most of his time on personal injury cases, said his clients decided not to fight “strictly, as I understood it at the time, for economic reasons. I think they just wanted to pull out of Corpus. Maybe business wasn’t good enough to justify the expense of defending the injunction proceedings.”

There have been no obscenity trials at all since the U.S. Supreme Court handed down Miller.

• Midland-Odessa: As a general rule, West Texas cities have been more tolerant of adult bookstores and theaters than East Texas, providing students of popular morality with a fertile field for speculation. Odessa, for example, is a fairly wide-open town. For a while in early 1974 the police tried to make Ector County a little Fort Worth, but after attorney Warren Heagy won a hung jury (5-1 for acquittal) on a hardcore film, things tapered off. Two bookstores and two theaters continue to operate. Midland, on the other hand, is as pure as the Highland Park it aspires to be. There are no adult bookstores or movie houses there. “I don’t think Midland was ever stimulated,” said one Odessa lawyer.

As happened in San Antonio, a prosecutor’s ingenious legal scheme against pornography usually results in a federal court lawsuit brought by the defense to make him stop. More than a dozen such cases from seven Texas cities have now been consolidated before the three-judge panel in Houston. The court is being asked to decide the constitutionality of

• San Antonio’s use of the felony “criminal instruments” tactic,

• Fort Worth’s removal of seats and electric wiring under search warrant provisions that apply to “criminal implements,”

• Permanent injunctions to close down adult movie houses,

• San Angelo’s use of the “nuisance statute” for the same purpose, and

• The Texas obscenity law itself, as recently rewritten by the Court of Criminal Appeals.

An Assistant Attorney General of Texas, Lonnie Zwiener, has acknowledged that there is “police bad faith” and “harassment” in some of the cases before the panel. A decision sometime in January is expected from the three judges (John Singleton, William Taylor, and Joe Ingraham). It should be decisive, one way or the other; Singleton is clearly discontented with the way Miller has “made the federal court a joint board of censors,” and feels that “this case-by-case analysis… has got to go, one way or the other.” Any tactic the court upholds is likely to be widely used the next day.

Is there really any such thing as a “community standard” out there in every American city, town, and village, just lying around waiting to be discovered, as Miller seems to assume? What has happened in Texas suggests that the Supreme Court’s theory may not be very realistic. There are differences in the bigger cities around the state, to be sure; but they seem to owe more to personalities, politics, and even luck than to any deep moral cleavages. Is softcore San Antonio really a more fastidious community than Dallas, where hardcore continues to thrive? Are the people of Fort Worth really more up-in-arms about smut than anybody else in Texas?

From his vantage point in Houston Clyde Woody seems to have hit the nail on the head: the “community standard,” if there is any such thing, is mostly the product of combat between the officials who enforce the law and the lawyers who defend those accused of violating it.

The San Antonio Grand Jury reports, picked up by the scandal mongering local media there, do not reflect community sentiment as much as they create it. The Fort Worth anti-porn campaign has all the earmarks of a shrewd and timely political ploy; anyone who thinks the convictions prove a “standard” must first consider how many of them would have occurred without Shannon’s fanfare on Main Street.

The same doubts exist for communities that are taking a softer line. In Houston three different jurors—and perhaps the absence of a woman lawyer for the defense; who knows?—could well have tossed Deep Throat off the screen and propelled Carol Vance to a countywide crackdown. Certainly he could have softened the Houston scene just by using Shannon’s and Quinlan’s tactics regardless of courtroom victories; a sense of fair play is all that seems to have kept him from it. In Austin, a DA with the zeal of Savonarola and a vice squad with time on its hands practically cleaned out the town; is their work more indicative of a “community standard” than the mood of the two local juries that failed to find Deep Throat obscene?

If anything, the economic demand for porn has more to do with what is actually sold than any supposed “community standard” does. The hardcore merchants in Corpus found it better business to pull out of town than to pay big legal defense fees, leaving only softcore behind; does that prove Corpus has a softcore standard? If one answers yes, then how to explain Fort Worth, where a couple of hardcore stores have stuck out the storm like palms in a hurricane, presumably at a profit and not for charity? Are “standards” expressed in convictions or in sales? Or both?

If Texas cities do have real, identifiable, subtly-differentiated community standards about obscenity, nothing that has happened in the past eighteen months sheds much light on what they are. Instead Texas has, within broad limits, exhibited a random system of censorship. It is not censorship of great literature, but it is censorship nonetheless.

The main question, now that Miller has re-ignited the crusade against obscenity, is whether the whole thing is really worth it—worth the time and the money and the ugly legal bruises. Is there any reason for society to watchdog what adults see and read?

The moralists who answer yes are not all wrong by any means, a fact that individualists who pride themselves for defending “human values” all too often fail to see. The adult books and movies available in Texas are profoundly dehumanized. To pay ten dollars for a magazine that shows page after page of copulating genitals with only a rare face or two is to be reminded that pornography and eroticism can be two very different things, and that a legal attack on one need not be an attack on the other. Most of the stuff is trash, and a Grand Jury that says so is not off its rocker. Boredom is the most inescapable reaction to a heavy dose of the current porn, as the defense attorneys themselves freely admit. It is ultimately depressing, and “ultimately” comes very soon.

Good riddance, then? Tear down the walls, rip out the seats, dismantle the marquee? Defense attorney Mike Aranson says this:

“What’s important is not what they are going to do, but what they can do. The danger comes when you give any type of law enforcement group the unfettered power to make a decision about what to prosecute and what to censor. And while they may, in great beneficence, decide that they’re not gonna prosecute this book or this magazine, it’s still their decision.”

Joe Shannon in Fort Worth holds the power of peace or war over that city’s adult bookstores and movie houses. Fettered by very little except a consensus in the DA’s office, he has decided that certain kinds of things will be left untouched and certain other kinds will be harassed and prosecuted. To draw the line between the two he did not instigate a series of test cases to determine what the “community” of Fort Worth considered obscene, nor did he consult a popularly-elected Board of Censors; instead, he looked around for something clear enough for “the cop on the beat” to understand. He freely admits that the resulting line—actual penetration—is not required by the Texas obscenity law; “we have not chosen to get into” softcore simulated sex, he says, “even though I think it’s clearly prosecutable.” If he is successful he will have decided, largely on the basis of administrative convenience, what kinds of sexually explicit material the residents of Fort Worth can see and read.

Pornography, however scant its value may or may not be, has been around for a long time. Any gain in public morals that might ensue from pushing it back under the counter is insignificant compared to the damage done to some basic, prized freedoms when law enforcement officers are allowed to make public decisions like that.

Has there ever been a juror, judge, or prosecutor in Texas who declared that his moral fiber was frayed by the pornography from which he decided to shield his fellow citizens? In one city the prosecutors jokingly asked defense attorneys to swap films with them some time. “We’ve seen all these down here,” they explained. It is always someone else who must be protected.

- More About:

- Texas History

- Politics & Policy

- Film & TV

- Movie Theaters

- Longreads