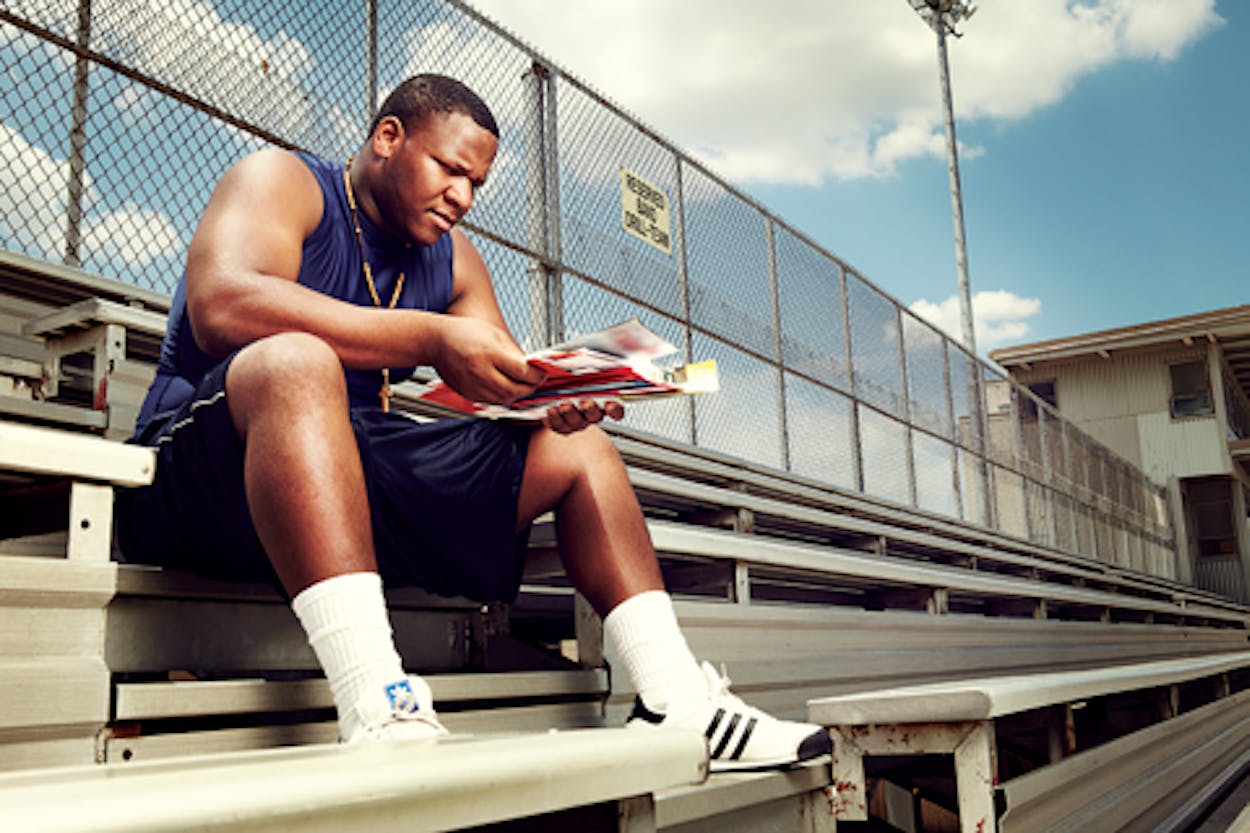

A coach from Georgia is lurking outside the Kimball High School gym in Dallas. Inside, Justin Manning, a defensive tackle who stands six feet two inches tall and weighs 275 pounds, looks beat. It’s not his social studies final. No, the kid’s vacant eyes are a sign of the burden—or, you might say, the privilege—of being a highly coveted high school football player. This year, Manning’s school has become a pilgrimage site for college coaches with a story to sell. Manning sighs. “It seems like they’re telling me what I want to hear,” he says.

Let’s not use the word “recruiting” to describe the strange thing happening to Manning. Recruiting is a fairy tale about a college coach and a kid in a letter sweater. Manning’s situation requires a word that conveys its high stakes, its enormous perils. Let’s call it the Negotiation. The Negotiation is pure business. Manning has a skill that’s valuable to a multibillion-dollar industry called college football. But he is bargaining at a severe disadvantage.

As far as the Negotiation goes, Manning isn’t a novice. In 2005, when he was still in elementary school, his brother DeMarcus Granger was one of the top twenty high school football recruits in the nation. “I remember his mail,” Manning tells me. “These big boxes that were full of mail, and I used to play in them.” Coaches from one school were so desperate to sign Granger, who was also a defensive tackle, that they showed up at Pancho’s Mexican Buffet, where the boys’ mother worked.

Granger eventually committed to the University of Oklahoma, in a ceremony televised on the Dallas Fox affiliate. But he never hit it big in college football. After a tryout with the Seattle Seahawks in 2010 failed to win him an NFL contract, his career petered out.

So Manning, who is more nimble, with a quicker move into the offensive backfield, stepped up. “My sophomore year,” he remembers, “we’re in a scrimmage against Roosevelt. [Kimball] had another defensive tackle starting in front of me. I had a fantastic scrimmage. I had, like, four tackles back-to-back.” Suddenly Manning found himself starting for Kimball alongside Isiah Norton, a highly regarded defensive tackle who later signed with Colorado State. After Manning’s sophomore season, a Texas A&M assistant coach showed up in person at Kimball and offered him his first scholarship. To date, 22 schools have offered, including Oklahoma, LSU, USC, TCU, and Arkansas.

As the offers piled up, Manning changed his Twitter bio to read, “I just wanna take my mama out of public housing!” But though a fat NFL contract would change his family’s circumstances, the terms of the Negotiation are stacked against him. Manning is being wooed by, to name but one example, University of Texas coach Mack Brown. Brown makes more than $5 million per year. Since Manning plays defense, he’s also being wooed by UT’s defensive coordinator, the defensive tackles coach, and the Dallas area recruiter. So imagine a boardroom table: On one side sit a CEO and his lieutenants, who together make upward of $6.5 million annually. On the other side sits Manning. He makes nothing.

But it gets worse. Manning is really good; he has a lot of CEOs chasing him. So take the fiduciary relationship above and make it even more perverse: On one side of the table sits a group of men who collectively make at least $50 million annually. On the other side sits Manning, who makes nothing.

“I’m just trying to figure out what’s real and what’s not,” Manning says.

Coaches aren’t the only ones Manning is dealing with. The media are parties to the Negotiation too. As soon as his classes end in the afternoon, Manning’s cellphone buzzes with calls from recruiting reporters working for websites with names like SoonerScoop and Orangebloods. These sites, which fans like me pay $100 per year to subscribe to, are part of the Rivals network, a collection of college sports message boards and original reporting that was sold to Yahoo in 2007 for a reported $100 million. At least fifty such news organizations are covering Manning. He can remember only one of the reporters’ names. The calls come as late as eleven-thirty at night.

Fans are hounding Manning too. Not long ago, a TCU fan saw him at Macy’s, recognized the name on his letter jacket from a recruiting website, and ran up to give him the Frog sign. A fan from another school, who thought Manning was going to sign with a rival, tweeted at him that he was another overrated recruit from inner-city Dallas.

Was that weird? I ask Manning.

“It wasn’t weird,” he says evenly. “It happens all the time.”

The national letter of intent Manning will sign at the culmination of the Negotiation, next February, consists of three pages. Here’s what the fine print says: the coaches promising Manning a starting job are offering him only a one-year scholarship. Though every coach says he wants Manning to get a great education, the seventeen-year-old will be easily fireable. The contract also doesn’t fully explain that if Manning wants to change schools, his ability to transfer can be restricted at the whim of the athletics department.

Is your mom helping you? I ask Manning.

“My mama don’t know too much about college,” he says. “The only school she knows is Oklahoma.”

How about your dad?

Manning exhales in a way that indicates that Dad isn’t around.

Is your coach helping you?

“Nope.”

Justin Manning will make the biggest decision of his young life by himself. And no alarms will go off at NCAA headquarters. No muckraking articles will be written. According to the terms of the Negotiation, it’s perfectly normal for a seventeen-year-old kid to confront a multibillion-dollar industry all alone.

What’s happening to Manning is happening right now to nearly four hundred Texas high school recruits. Some have family members and high school coaches guiding them through the Negotiation. But even in the best-case scenario, none will come to the table with equal firepower.

The schools, of course, are desperate too, and this is where the Negotiation becomes even more fraught with peril. Since 1948, the NCAA has attempted to police cheating in recruiting by punishing schools that break the rules. The NCAA regulates everything from how often a coach can visit a recruit in his home to which days he can send him a text message. The most flagrant violations become the stuff of legend. In 1989 the testimony of Bay City wide receiver Hart Lee Dykes, who was given at least $23,000 and a sports car, helped put four different colleges on NCAA probation. In 2009 the father of Heisman Trophy–winning quarterback Cam Newton allegedly asked for more than $100,000 to sign his son.

Texas has excelled at cheating. During the eighties, seven of the Southwest Conference’s nine member schools were slapped with some form of NCAA sanctions. A typical violation consisted of a booster—an über-fan who donates to a school—giving money to a high school player to entice him to play for the booster’s alma mater. In the most infamous case, SMU boosters were caught paying players tens of thousands of dollars in 1986. Former (and future) Texas governor Bill Clements, who was on the SMU board of governors, recommended that the school “phase out” the payments; the money promised to high school players was too much to cut off all at once. That led to the so-called death penalty, which forced the Mustangs to suspend their football program for two years.

Of course, to some the NCAA’s police actions are a sham. If UT can make $96 million a year in football revenue, critics argue, players deserve more than the few thousand dollars they could cadge from a booster. In this telling, it’s the “amateur” system rather than the greasy payoff that’s corrupt. In his recent treatise in The Atlantic, the historian Taylor Branch pointed out that the term “student-athlete” was adopted by the NCAA in the fifties as little more than a clever method of protecting itself from injury lawsuits.

The NCAA doesn’t see it that way. Lately, their police efforts have focused on a new kind of cheater. Street agents have been involved with NCAA basketball for at least a decade but are a more recent arrival to the world of college football. The street agent is a hustler, a hanger-on. He takes the old Southwest Conference model of cheating and gives it a twist. Instead of money going directly to the player, it goes to the street agent, who shops the recruit to colleges like a poor man’s Scott Boras. The player accepts the arrangement because—at least, this is the street agent’s pitch—he can’t guide himself through the bewildering process of recruiting.

The first reports of street agents in Texas began appearing in 2009, on Longhorns fan websites like Barking Carnival and Recruitocosm. NCAA investigators began making trips to Texas to interview high school coaches, building a theory for how street agents had infiltrated the state. What they found was that street agents were gaining a foothold through 7-on-7’s, the summer passing tournaments that are responsible for the boom in Texas quarterbacks. “The rise of 7-on-7’s has made this more of a problem than maybe historically it was,” explains Marcus Wilson, an associate director of football enforcement for the NCAA. Wilson adds, “But it’s a constantly evolving group of people, so we don’t know all the street agents out there.”

In Texas, one alleged agent stood out: Willie J. Lyles. Before Lyles’s run as a recruiting power broker was over, he would be called a “parasite,” a “rat,” and an “imbecile who desires fame.” All of those things are common enough in college football. What worried fans and athletic departments alike was that Lyles was operating in a way that was pretty brilliant.

“I was like this big bad wolf that was snatching kids off the street and sending them to college,” Lyles tells me of his reputation. “But no one knew or understood who I was.” Lyles grew up in the South Park neighborhood of Houston. His father, Willie Lyles Jr., works as an aerospace engineer at NASA and raised him in a strict Christian household. The family’s pastor, Dennis W. Young, says, “What is coming out is at the opposite end of what I knew [Lyles] to be and what his parents raised him to be. He was well trained.”

Lyles is a portly man with a shaved head and close-trimmed beard. He exudes a certain magnetism. He graduated from Houston’s Lamar High School in 1998 and completed eighty hours’ worth of credits at Texas Southern, where he studied history. Though he played only a couple of years of high school football, he always wanted to work inside the game. “That, or I wanted to be a city planner,” Lyles says. He later became a trainer at a firm called Speed Dynamics, where he met high school players, working with them at Houston’s Hermann Park.

From the beginning Lyles had a knack for developing relationships with some of the best players in the area. Bobby Burton, the dean of Texas recruiting reporters, first encountered him in January 2005. Two top recruits, R. J. Jackson and Brandon LaFell, were holding a party at Boudreaux’s restaurant in Houston to announce that they were signing with LSU. The event was a mob scene of friends, family, and reporters. But when Lyles introduced himself to Burton, Burton thought, “Who is this guy?”

“I’d heard of long-lost uncles coming back and playing a role in recruiting,” Burton says. “Or the dad that hadn’t been part of their life. But that was the first time it was a true third party.” Lyles now contends he wasn’t at the ceremony at all.

In 2006 he went to work for Muscle Sports, a New York–based scouting service. Scouts are additional parties to the Negotiation. They gather information about high school players. Then they sell that information to data-hungry college coaches who want to locate the best players. This is perfectly kosher. The problem, says the NCAA’s Wilson, “is you’ll have individuals or organizations that masquerade themselves as a scouting service but are in fact funneling prospects to certain schools.”

At Muscle Sports, Lyles met another scout, Charles Fishbein, who soon left to start his own firm, Elite Scouting Services. Lyles became Elite’s man in Houston, and for several years business was good. Their clients included UT, LSU, Florida State, Oregon, and others. But in January 2010, Fishbein and Lyles split. Fishbein says he suspected that Lyles was making side deals with schools. Lyles claims he simply wanted to set up his own business, where he was the boss. Later that year, he formed Complete Scouting Services.

Lyles’s firm began to collect contracts: $25,000 from Oregon, $6,000 from LSU, $5,000 from the University of California. As a self-professed scout, Lyles had free run of Houston high school fields. According to Fox Sports’ Thayer Evans, he turned up one day at Clear Springs High School, a sprawling red-brick building in League City, outside Houston, and showed an Oregon assistant coach around. Lyles’s reach was wide. He was involved, however elusively, with players from Central Texas, players from the Metroplex, even a player from Thibodaux, Louisiana. On college football websites, Lyles was connected to LaMichael James, a running back who signed with Oregon, and Trey Williams, a running back who signed with Texas A&M. But it was difficult to tell whether Lyles was running these players’ recruitments, trying to run them, claiming to run them, or—perhaps least plausibly—simply serving as a scout.

Lyles had butted into the Negotiation. The coaches, reporters, and alumni that crowded around the seventeen-year-old players now had to deal with a new figure, one who was fast becoming the biggest recruiting power broker in the region. The end, however, was near. After Bobby Burton noticed that Lyles was hanging around a Temple running back named Lache Seastrunk at events, he alerted the investigative reporters at his parent company, Yahoo. The fall of Willie Lyles was set in motion.

Mack Brown folds his hands on his big desk and talks in a sorrowful voice about street agents. This is personal for Brown. His career at UT is built on a domination of recruiting that earned him the nickname Coach February. Since arriving in Austin, in 1998, Brown has shepherded more standout high school players through the Negotiation than any coach within five hundred miles. Lately, though, street agents have made it tougher. They’ve walked onto the turf in Austin during recruiting events. They’ve walked right up to Longhorns coaches and introduced themselves, usually as “a friend of the family.”

“Well,” Brown recounts, “you live in Houston. And this kid’s outside Dallas. So how did you become ‘a friend of the family’?”

Brown won’t mention any street agents by name. He won’t even call them street agents—his politically correct ears are too fine-tuned for that. Brown calls them third parties. But he knows exactly how they operate. A street agent rarely comes right out and asks the Longhorns for money. Brown says the question is phrased more like “Could I come and talk to you about my guy?” At that point, the UT coaches are told to cut off contact. What bugs Brown is that street agents have cost him some of the best recruits in the state. “You lose some,” Brown says. “There’s no question about that.”

It’s difficult to assemble the history of the street agent. Larry Coker, head coach at the University of Texas at San Antonio, remembers a handful working South Florida in the nineties, when he was at Miami. “I don’t think it was widespread at the time, but I did notice them on a couple of kids,” Coker tells me. “They had a broker, an agent—whatever you want to call it—speak in lieu of the family.” But the street agent remained unknown in Texas. “I had never heard of that,” says Bob Shipley, the head coach at Brownwood High School, who sent both his sons to play for the Longhorns, in 2004 and 2011.

It wasn’t until three or four years ago that Brown began to fear that high school football was going the way of high school basketball. Basketball has long been overshadowed by the American Athletic Union (AAU), a league in which a high schooler often plays for different coaches and with different teammates. AAU coaches become so influential, it’s argued, that they manage the recruitment of players as their de facto agents. They may direct high schoolers to a university with a particular shoe contract (AAU teams are sponsored), or they may deliver a student to a college where they end up finding a job themselves. While Texas A&M was recruiting star center DeAndre Jordan in 2007, they hired his AAU coach, Byron Smith, as an assistant. Jordan signed with the Aggies.

According to Brown, the rise of 7-on-7’s has given Texas football its own shadow league, conducted outside the purview of high school and college coaches. “That’s when the kids are vulnerable,” Brown says. “Especially the kids who don’t have very much money, maybe have parents who don’t understand what’s going on at home as much. They’re more vulnerable to someone who would try to come in and help them.” The kids may not even need the help, but their circumstances make them willing to listen.

Brown doesn’t just fear a shakedown. He fears a crack-up of the relationship between a player and his high school coach. “I actually had a young man tell me two years ago, ‘My performance in 7-on-7’s will be more important to my recruiting than what I do during the season with my team,’ ” Brown recalls.

Another time, Brown was sitting in a high school coach’s office, chatting with him and a player who had committed to UT. Brown asked about the recruit’s Signing Day plans. The coach said his player would be signing his letter of intent with his teammates at the school. But the recruit informed him that, no, he had an all-star game with another team that day. The high school coach, Brown says, was humiliated.

Brown has a standard message for a recruit who refuses to divorce his agent. “It’s your decision, it’s your life, it’s your family,” he tells them. “If that’s what you want to do, fine. But you won’t be at Texas.”

The Longhorns actually had a near miss with Lyles. Beginning in 2008, ESPN reported, UT had a scouting contract with Elite Scouting Services, where Lyles was employed. It was during this period that Major Applewhite, UT’s running backs coach, called Lyles and asked if they could meet for dinner. The two men dined at Live Sports Bar in Houston while watching Oklahoma and Florida play in the BCS championship game. According to Lyles, Applewhite asked him to convince Lache Seastrunk and Trovon Reed, a wide receiver from Louisiana, to come to UT’s upcoming Junior Day. UT says Applewhite did no such thing and asked Lyles only for scouting information.

Both agree the Longhorns were becoming suspicious. After the contract with Elite ended, the school never paid Lyles or his associates again. Lyles claims Mack Brown later helped precipitate his downfall. I ask Brown if he shared information with the NCAA. “You always talk to the NCAA when it comes to any third party,” he says obliquely.

So Mack Brown hates street agents—er, third parties. But the picture he paints of the rest of the recruiting landscape is almost as perverse. He told me about one recruit who recently answered his phone, perhaps expecting a call from a reporter, only to hear another voice. It was Mack Brown’s. Only Brown never called the kid. “It is very likely,” Brown huffs, “that some recruiting reporter called him and acted like they were me.”

Wait, an impostor Mack Brown is calling recruits in Texas? I ask. “No question,” Brown says. He thinks the reporter was trying to wheedle information from the recruit by impersonating the coach.

That’s not the only trick. Part of Brown’s sales pitch is his old-fashionedness. He insists recruits come to his office to get scholarship offers in person. But as soon as a recruit leaves the office, something strange often happens. A recruiting reporter will contact the player and say, “Mack Brown just called and told me you committed to UT.” It’s another trick—not only because Brown isn’t dishing to recruiting reporters but because in order to share the news so quickly, Brown would have to bend the laws of space and time.

“We’re not supposed to talk to the recruiting reporters about kids,” Brown says. “But some [rival coaches] will call the reporters and say, ‘Call this kid and tell him you heard this about Texas.’ ‘Call this kid and find out what he’s really thinking.’ ” Though a coach’s contact with recruits is heavily restricted, by teaming up with a reporter, Brown suggests, he could get a kid to divulge sensitive information, and even influence him during the Negotiation.

Now, Brown is known as one of the most polite coaches in the business. So I’m startled when he reveals what some colleagues have told him. “You can’t make it,” they tell Brown, “unless you deal with some of the third parties.” When Brown relates that, he looks terribly, terribly sad.

Watch Lache Seastrunk’s highlights: you’ll notice that he always seems to find the corner. Once there, he turns on the jets and leaves safeties sprawled on the turf. When the recruiting reporters started ranking the class of 2010, Seastrunk rated four or five stars—the highest designations. But he came with an asterisk: he and Lyles had become friendly at a 7-on-7 tournament. “What is a guy from Houston doing with a guy from Temple?” Bobby Burton remembers thinking.

Seastrunk fit the parameters Brown talks about for suggestible kids. His mother, Evelyn, had been in and out of jail. He was mostly raised by his grandmother, Annie Harris. By 2009, Lyles had moved into Seastrunk’s life. A few times, on the night of a big game, he even stayed at Seastrunk’s house. (Lyles denies a romantic relationship with Seastrunk’s mother.)

Lyles describes himself as Seastrunk’s mentor. “He’s one of the nicest kids you’ll ever meet,” says Lyles. “He would just call and ask me questions.” Lyles accompanied him during a visit to USC. When Seastrunk was called by the recruiting reporters, he raved about USC. But then Coach Pete Carroll—who was dealing with his own NCAA scandal, involving Reggie Bush—fled to the NFL. “It was a really big disappointment because . . . you’ve got a lot of guys committed to [USC] and you just up and leave,” Seastrunk told the Killeen Daily Herald.

That year, Lyles accompanied Trovon Reed, the wide receiver from Louisiana, to the Longhorns Junior Day event on February 28. He even walked into Mack Brown’s office with Reed. “It was all good,” says Lyles, who remembers meeting Brown’s wife, Sally. But when Lyles tried to accompany Seastrunk into Brown’s office later that same day, Brown and the Longhorns staff got wise. A Longhorns staffer stopped him. The Longhorns later ended their pursuit of Seastrunk and Reed altogether, and Lyles has bashed UT ever since. “Another week, another Longhorn loss,” he tweeted last November. “Life is good.”

Seastrunk’s recruitment dragged on toward Signing Day in early 2010. He had only one Texas university, Baylor, on his list of finalists—indeed, part of the in-state frustration about street agents is that they usually seem to be directing recruits elsewhere. Seastrunk began to favor Oregon. With USC facing NCAA sanctions, Oregon was emerging as the best team in the Pac-10 Conference. Coach Chip Kelly’s “blur” offense was making stars out of smallish running backs.

Also, Oregon was paying Lyles $25,000 for his scouting services.

Evelyn Seastrunk didn’t want her son to go to Oregon. She refused to cosign his letter of intent. “Lache came to me and said his mother was threatening him,” Lyles later told Yahoo, “saying she wouldn’t sign his letter of intent unless he went to the school she told him to go to.” Lyles negotiated a work-around in which Seastrunk’s grandmother would sign the letter. Seastrunk signed with Oregon on February 3, 2010. “God wanted me to be there,” he later said. And presumably Lyles did too.

The $25,000 check that Oregon mailed to Lyles for scouting services became the first piece of evidence that something was amiss. Yahoo sportswriter Charles Robinson reported its existence in a story in March 2011. Evelyn Seastrunk claimed she didn’t know about it. “If Willie Lyles collected $25,000 off my son, he needs to be held accountable,” she told ESPN. “The NCAA must find out for me. I don’t know how to digest someone cashing in on my son.”

The Yahoo report about the check caused a panic in Oregon’s athletic department. To maintain the slender fiction that Lyles was a scouting service—providing information the Ducks could use or reject as they saw fit—Oregon had to produce, well, some evidence that Lyles was providing a service. A booklet, a video, something. Lyles shoved some recruiting profiles into a folder and mailed it to Eugene.

These recruiting profiles became the second ironclad piece of evidence. Most of them involved athletes who were already in college and would have been useless to Oregon recruiters. One of the kids Lyles included in his report was dead. Lyles now says the profiles were a rush job to pacify the NCAA; he’d provided lots of legitimate scouting information to Oregon over the phone. In a touching show of faith—or chutzpah—Lyles had sent a second invoice for $25,000 to Oregon that spring, for work he says he did on future recruiting classes. The invoice was not paid.

Lyles realized then that his career in college football was over. “Once I saw they were really trying to tarnish my reputation, I knew it was a wrap for me,” he says. “And you’ve got people like Jerry Sandusky out there. When you really put things in perspective, I’m like, ‘This is bullshit!’ ” Though his pastor had little idea what kind of wormhole Lyles had opened in the college sports universe, when Lyles came to him for help, he simply suggested he pray.

Lyles could have clammed up. But suddenly he was a media obsession, as sought after by reporters as his former protégés. He began to confess. Last summer, Lyles admitted to Yahoo, “I look back at it now, and [Oregon] paid for what they saw as my access and influence with recruits.” So, for the record, in case anyone needed confirmation, Lyles was not a mere scouting service. He was a third party.

Sportswriters like Jason Whitlock charged that Lyles’s confession hadn’t just nailed Oregon; it had put his players’ eligibility in jeopardy as well. But Lyles tells me the NCAA’s implicit threat was that if he didn’t talk to its enforcement officers, penalties would have come down on Seastrunk. So he talked. (The NCAA’s official investigation is still ongoing.)

Meanwhile, his players have stuck by him. Lyles was with LaMichael James when he was picked by the San Francisco 49ers in the second round of the NFL draft in April. “He’s never steered me wrong,” James told a reporter. “He’s never given me bad advice.” Seastrunk transferred from Oregon to Baylor after his freshman year, citing the need to be close to his ailing grandmother. “They’ve never been mad at me,” Lyles says. “Ever.”

So we were left with a big-time scandal, a $25,000 check, and a bunch of embarrassed coaches. But exactly what kind of evil did the Willie Lyles affair reveal?

One take is that colleges like Oregon have discovered a method of villainy even worse than what transpired during the Southwest Conference’s heyday. But believing this requires any Texan who lived through the eighties to play dumb. Craig James—the former SMU running back and kamikaze U.S. Senate candidate—once wrote that a “really good blue-chipper” could command a $50,000 upfront payment, plus a car and a monthly allowance. So if football players are for sale again in Texas, the price has dropped considerably.

Mack Brown’s lesson is that street agents have wedged themselves in between a recruit and his high school coach. If he had his way, he would restrict the Negotiation to the recruit, his parents (or extended family), and his coach. But as Justin Manning shows us, the last two don’t always take part in the process. And as Brown himself tells us, his college-coaching brethren can’t necessarily be trusted.

Willie Lyles wasn’t around to speculate about lessons. Stung by media criticism, he became a ghost. He worked at a Spec’s liquor store in Houston for a while. When I asked him one night this summer what he was up to, he said, “Just working for a living.” He added, with typical mystery, “I don’t really care for people to know too much.”

Another take on the Willie Lyles affair is that the man himself is a sideshow, a distraction. The real source of evil—the thing college football fans should fear—is the NCAA’s system of amateurism.

One afternoon this spring, I visited the modest Houston apartment complex called Hearthwood where Lyles ran his business. He wasn’t there, but I wanted to see for myself the heart of his empire. Hearthwood consists of a series of light-brown brick and stucco buildings arranged around neatly kept gardens. If you stand in the parking lot, you can see the roof of Reliant Stadium peeking over the treetops.

How much is an apartment? I asked the woman in the realty office.

A one-bedroom runs about $600 a month, she said. Slightly more depending on the condition of the carpet.

I walked through courtyards, past teenagers talking on cellphones, until I made it to building number 8429. The $25,000 check Oregon sent to Lyles for scouting services had been delivered here. According to the invoice, Lyles’s company was located in “suite 37,” which seems pretty grand for Hearthwood.

The idea of Lyles sitting in a cheap condo and playing the evil ruler of college football is comical. Or maybe pathetic. Indeed, the truth is that for all the hand-wringing about street agents, Lyles was a small-timer. “I wasn’t making money hand over fist,” he says. “I wasn’t driving around in a fancy car and all that stuff.”

No, what’s worth remembering about the Willie Lyles affair is this: we’ve decided to protect kids from street agents. That’s probably good. But what we haven’t protected them from is college football.

It’s college football that puts a seventeen-year-old at an impossible disadvantage. Take the case of Student Athlete Mentoring Foundation, a nonprofit started by a former coach named Steve Gordon. Before it came under scrutiny from the NCAA, SAM sought to help inner-city kids manage the Negotiation. The foundation would send them to football camps they couldn’t afford or on unofficial trips to visit colleges. The nonprofit took no money other than what it received in donations.

Last year, it was revealed that SAM spent $2,700 on travel and other incidental expenses for a low-income recruit whose parents were absent and unable to support him. When the NCAA found out, they suspended the player for two games and forced him to pay back the $2,700. “We get labeled with ulterior motives,” says Gordon, “because there’s no possible way we could do it with just wanting to help the kid out.”

Or take Justin Manning, negotiating all alone for a job that, ironically, he will perform for free. When I ask Manning if he’s ever heard of a street agent, he looks at me blankly. In college recruiting, amateurism is a pair of handcuffs reserved for the person who needs help the most. The scary part isn’t that a seventeen-year-old football player would get himself an agent. The scary part is that, these days, he probably needs one.

The former headquarters of Willie J. Lyles stand empty. The man is out of business. But if you think college football is an honest game, then, young man, I’d love to talk to you about a scholarship.