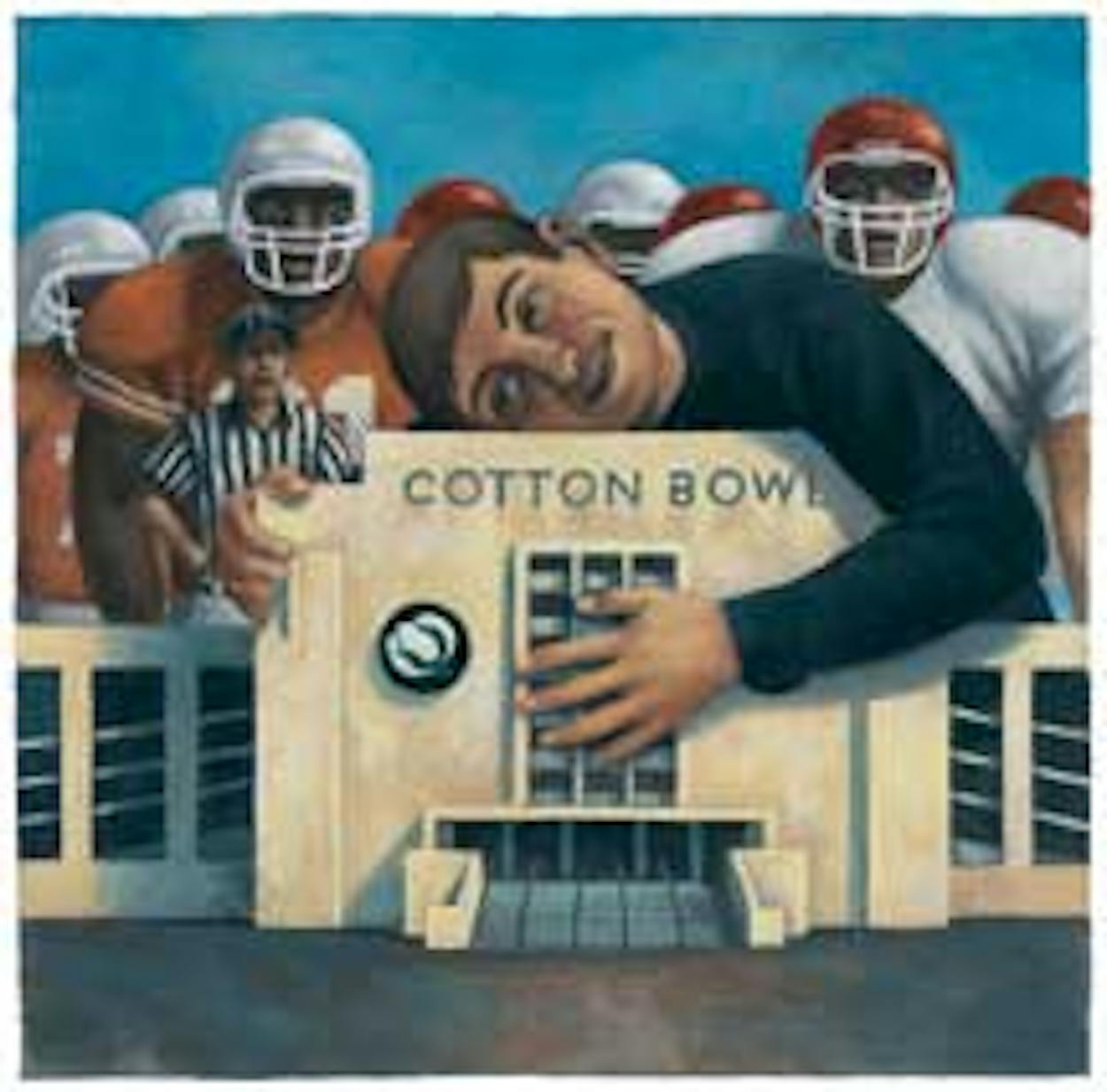

Any appreciation of the Cotton Bowl, the giant concrete mausoleum nestled in Dallas’s Fair Park, is bound to sound like a eulogy. The Cotton Bowl is 78 years old, and like an aging ex-linebacker, it has staggered unevenly into the new millennium. The stadium has no retractable roof, no skyboxes, no sushi bars. Parking is often best accomplished in the front yard of a South Dallas resident charging $10 a car. The long and vibrant history of the House That Doak Built is neither as long nor as vibrant as the line to the nearest men’s room—if you can find one at all. Truth be told, the Cotton Bowl is probably the shabbiest sports stadium I’ve ever been to (honorable mention to Dallas’s old Sportatorium, a tin can used for pro wrestling). But for all its obvious infirmities—in fact, because of them—the Cotton Bowl is also my favorite. I would wrap my arms around it if I weren’t afraid of the cement facade crumbling in my hands.

Nearly everyone who has braved the Cotton Bowl has a story. Because most of us pass through its turnstiles only once a year, usually for Texas-Oklahoma, Grambling-Prairie View A&M, or the New Year’s Day bowl game, we never quite master the peculiarities, the fraught possibilities of the “game day experience.” Just before the kickoff to the 2005 Texas-Oklahoma game, I handed over my ticket and started down one of the stadium’s exceedingly narrow concourses. Almost instantly, I found myself frozen behind a massive pileup of Longhorns fans who were crammed body to body in the corridor holding corn dogs. While Vince Young was racing down the field, we stood in perplexed silence, finally standing on our tiptoes to see . . . another group of Longhorns fans, equally motionless and facing us. As the seconds slipped away, we Longhorns remained immobilized. The journey from the gate to my seat, a distance of about a hundred feet, took the better part of half an hour.

I thought I had simply arrived too late to see the Cotton Bowl’s glory days. But it turns out the Cotton Bowl was never exactly a state-of-the-art facility. Bob Lilly, who played there ten seasons with the Dallas Cowboys, remembers its considerable quirks. There was the grass field that had to be painted green when it died off in the winter; Bubbles Cash, the famous stripper sashaying up and down the aisles; the locker room that did not comfortably seat fifty Jurassic-sized football players and in which pregame rituals required a triumph of geometry even greater than Tom Landry’s flex defense. And the crowds, which for the newbie Cowboys franchise could be awfully sparse. “In 1961 and ’62, I remember we’d have a misty or rainy day, and all the fans would get under that second tier,” says Lilly. “It was like we didn’t have any fans at all. We might have fifteen thousand people there, but you couldn’t see ’em.” Mist and rain turned out to be the least of it. Arctic conditions regularly visited the Cotton Bowl Classic, resulting in oddities like 1979’s Chicken Soup Game, in which Notre Dame’s Joe Montana needed halftime nourishment to face the frozen tundra.

But the nagging problem that has dogged my favorite stadium in recent years—the one that has called its very existence into question—is the lack of headlining talent. For 55 years, the Cotton Bowl Classic was the showcase for the Southwest Conference champs, a victory lap for the likes of Doak Walker, Sammy Baugh, James Street, and Quentin Coryatt. Yet in the late eighties, the conference and its champions declined in quality, and as the SWC met its sleazy demise, in 1996, the Cotton Bowl was marked with second-class status. When the nation’s premier bowl games formed the Bowl Championship Series, in 1998, the Cotton Bowl was left on the sidelines.

Long-term prospects have only been getting dimmer: Last February, the proprietors of the Classic announced that in 2010 they were abandoning their home to move to Jerry Jones’s minor construction project out in Arlington. The Red River Rivalry seemed lost too, destined for a “home-and-home” in Austin and Norman, before $50 million in promised improvements convinced the schools to extend their lease until 2015. Some would say the death of the old stadium is inevitable. How can it compete with Jones’s $1 billion Taj Mahal, the one with the iconic arches, retractable roof, sixty-yard-long video board, and two hundred luxury suites? Even if we allow for Jones’s penchant for overstatement, his stadium has already made North Texas into a mandatory football destination again—he has secured the 2011 Super Bowl and is negotiating an annual showdown between Texas A&M and Arkansas. The Cotton Bowl Classic hopes that moving out of the old place will give the game a frisson of excitement. “Unfortunately, a lot of young men don’t remember Doak Walker, Roger Staubach, or, heck, even Troy Aikman,” says Rick Baker, the Cotton Bowl president. “They want to play where Tony Romo plays.”

But it’s a mistake to think Jerry World will make the Cotton Bowl obsolete. Just the opposite: It will only increase its worth. Anyone who has been to an NFL stadium lately knows that it has become a rather ear-rattling place to spend a Sunday afternoon. In a misguided attempt to seem hip, NFL owners have taken their wonderful product, pro football, and hidden it inside a rock concert—interlacing out patterns and off-tackle plays with Top 40 hits, excess pyrotechnics, and advertisements read by wrestling announcers on the lam. I like Alicia Keys’s music as much as the next guy. I just don’t understand why it should play during a huddle. No one, not even Jerry Jones, has yet figured out how to blend football and show business in a way that is less than obnoxious. Watching the NFL live makes even a football-mad guy like me want to retreat to a place for quiet contemplation.

A place like the Cotton Bowl. Do I appreciate the need to build modern stadiums? Of course. But would I risk any bit of the football experience in exchange for sushi and a scoreboard longer than most punts? Heck, no. That’s why, with or without its $50 million worth of improvements—which, Longhorns and Sooners, will include 16,000 additional seats, a $5 million HDTV video scoreboard, more concession stands and restrooms, a new media center, and two light-rail stops at Fair Park—I will happily submit myself to the Cotton Bowl’s eccentricities. I will plow through the mazelike concourses, I will wander the fairgrounds like Moses looking for a restroom. One denizen of one of the Internet message boards I frequent, someone who appreciates the value of shabby oddities, said it best: “We should play the Texas-Oklahoma game in the Cotton Bowl until the stadium falls down around us. Then we should play it in the rubble.”

- More About:

- Sports

- College Football

- Dallas