This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

On Friday nights in Amarillo, after the high school football season and its hopes have faded, there is a restless energy on Western Street, where students from Amarillo High and its crosstown rival, Tascosa, idle in empty parking lots, leaning out the windows of their pickups to discuss the night’s possibilities. The uneasy tensions of adolescence reverberate along this broad boulevard lined with fast-food joints, convenience stores, and all-night drive-throughs, where the jocks and the punks and the kickers and the stoners while away their weekend evenings. Here, the jocks—sometimes called the White Hats for the ball caps they regularly wear—reign supreme: With a sense of certainty and the self-assurance of those who know their worth, they drive along Western Street, surveying the landscape as if it were their own. The objects of their scorn are the misfits who stand at its fringes: punks in patched-up pants and black leather jackets and the occasional blue mohawk. Over the years, the punks say, the White Hats have mocked and bullied them without mercy, spitting on them as they walk down the hall at school, roughing them up in the restroom, and swinging at them, on occasion, from the back of pickup trucks with bats. “Hey, freak,” the jocks would yell from their cars at the punks passing by on foot, scattering broken glass along the pavement as hurled beer bottles missed their mark.

Amarillo turned a blind eye to these cruelties until a brawl of such extraordinary violence erupted one night on Western Street that a Tascosa High football player would later say it “seemed like a dream.” It happened on a Friday night much like any other, a few weeks before Christmas in 1997. Rumors had been circulating at Tascosa all week that the football players—the Rebels—were going to fight the punks. The previous weekend there had been a scuffle between the two groups outside a coffee shop on Western Street at which seventeen-year-old Dustin Camp, the ruddy-cheeked center for the junior varsity team, had gotten into an argument with several punks. It had quickly escalated: Dustin’s windshield had been smashed, and though he denies it, the punks say he had taken swipes at them with his car before peeling off down the boulevard. Now he had returned to the coffee shop to see how the rematch would unfold. Beside him in his prized 1983 Cadillac sat varsity tight end Rob Mansfield and in the back was Rob’s friend Elise Thompson, a poised, serious-minded girl who would graduate as the valedictorian of the class of 1999. Elise had heard the rumors, but she didn’t believe they were anything more than the usual bluster. There was often such talk, but rarely did the boys do anything more than throw a few punches before hightailing it out of there.

As Dustin turned his Cadillac onto Western Street, the coffee shop came into view: A large group of boys in varsity jackets stood outside, along with dozens of students who had gathered to watch. Several punks, armed with bats and chains, soon approached, challenging the jocks to fight; the melee began in the parking lot across the way with a ferocity that sent a chill through Elise. Alarmed, she assumed that Dustin would take her and Rob home, but he steered his Cadillac toward the action, weaving through the boys, who wrangled with one another under the streetlights. To his left, he caught a glimpse of one of his good friends, Andrew McCullough, being beaten by several punks. It was then, Elise later recalled, that Dustin “snapped.” Veering toward the crowd, he knocked one of the punks off his feet and onto the hood of the Cadillac; the boy stared in startled amazement before falling off to the side. “Let’s go,” cried Rob as the punks pummeled the car with bats and fists, making a thunderous racket. “Let’s get out of here!” Dustin drove hurriedly toward the exit, then changed his mind; circling back around, he jumped a median as he picked up speed. Spotting a punk, nineteen-year-old Brian Deneke, striking someone, he drove steadily toward him. Brian turned for an instant as the headlights drew nearer and struck the Cadillac with a chain when it came too close.

Then there was a thud. Brian rolled up onto the hood before sliding beneath the car. Elise closed her eyes and prayed that it was only the median she had felt underneath the wheels.

“I’m a ninja in my Caddy,” Elise heard Dustin boast. “I bet he liked that one.”

Elise looked over her shoulder, out the back window, and saw Brian crumpled on the pavement in a pool of blood. “I might have screamed,” she later testified. “I was having trouble forming words . . . The emotions were so intense—we were overwhelmed. It was insane.”

The Cadillac lurched out of the parking lot and sped toward the highway, leaving Brian dying on the pavement. In its wake, over the course of the many months that followed, the city’s sympathies would be divided as it waited for the football player behind the wheel to be tried for murder. But in those first searing moments, as the Cadillac fled the scene, all of that was unforseeable to the three teenagers inside. After what seemed an interminable amount of time, Elise leaned forward, trembling, and asked the question that was no doubt on their minds: “What if he’s dead?”

Amarillo straddles the flat, empty prairie that stretches north across the Panhandle toward Oklahoma—a stark landscape of wide-open sky and grassy plains unexpectedly broken just west of town by the upturned tailfins of Cadillac Ranch. It is arguably Texas’ last great Western outpost, a city of 169,000 bordered to the east by the ragged barbed wire of the stockyards and vast ranchland that extends to the horizon. Named “Amarillo” (Spanish for “yellow”) after the yellow wildflowers that bloom in its pastures each spring and the yellow soil that lines its creek banks, it is a place of contrary impulses: with rutted cowpaths and an interstate highway, honky-tonks and old-money enclaves, roughnecks and debutantes who fly to Dallas to shop at Neiman’s. Founded a little more than a century ago by bullheaded men who disregarded its wild and inhospitable weather and embraced the solitary freedom of the range, Amarillo has long been home to independent thinkers and contrarians. “In the fifties it was the cowboys versus the city slickers,” resident eccentric Stanley Marsh 3 recalled as he sat in his downtown office in a white brimmed cowboy hat and a fake sheriff’s star that read “Boss.” “And before that, at the turn of the century, it was the merchants versus the ranchers. I’ve been told they had a gold rope up at the cemetery so that merchants and ranchers—who smelled worse and who were considered speculators because they could lose everything on a herd of cattle—wouldn’t have to mix.”

Isolated by its geography and steeped in a stubborn frontier tradition, Amarillo has seen a good number of colorful squabbles in its history, including several in recent years: During the eighties, there was Boone Pickens’ vendetta against the Amarillo Globe-News for its scathing criticism of a university president whom he steadfastly supported; in the nineties there was the feud between Marsh and the wealthy Whittenburg clan that boiled over into a bitter civil lawsuit. For younger residents, whose rivalries play out on a smaller scale—typically in the form of high school football, a sport with an almost religious significance in this northern corner of the state—the city’s insularity gives rise to a heightened sense of antagonism, one that permeates teenage culture to its core.

During Hell Week, the seven days of pranks and vandalism that precede each year’s big game between the Tascosa Rebels and the Amarillo High Sandies, students give in to a feverish aggression: They paintball their opponents’ trucks and set off firecrackers on their lawns, egg houses and string trees with toilet paper, and most notably, get into fistfights around town. Throughout the season, Tascosa students are riled up at pep rallies by their pep squad, the Fanatics, cheering while football players pretend to beat and stomp on dummies dressed as their opponents’ mascots. Such rowdiness is winked at, its excesses as much a part of the culture as the machismo that informs the landscape: In the commons area of Tascosa High stands a statue of the Rebel, a cowboy with one hand resting firmly on his holstered gun.

Indeed, for Amarillo’s other rebels, the “freaks” who sit disinterestedly at the very top of the bleachers during pep rallies, the rah-rah atmosphere has an ugly side: It leaves little room for those without athletic ability or school spirit or, by extension, those who deviate from the norm. “Teenagers here pay a lot of attention to what your parents do, where you live, what name-brand clothing you wear, what church you go to, what kind of car you drive,” one mother lamented. “If you can’t compete, you’re an outcast.” If conformity has become a virtue at schools here as elsewhere, it is only reinforced by the fact that Amarillo itself is a stronghold of both cultural and religious traditionalism: Bordered by some of Texas’ few remaining dry counties, its FM dial carries an abundance of evangelical radio stations, and its newspaper regularly runs letters to the editor advocating the return of school prayer and creationism in the curriculum. “It’s like we’re stuck in the fifties here,” sighed more than one teenager. Even if the city has provoked a wholly original flamboyance in a few individuals, its conservative bent can be stifling for those who do not adhere to its expectations. “I believe it’s natural for a certain number of young people to do outrageous things like swallow goldfish or dress like Elvis or tuck their jeans into their boots to shock their elders,” Marsh observed. “When I was growing up in Amarillo, it was considered radical to turn your jeans up only once at the cuff, instead of twice like everybody else.”

No less radical by today’s standards, the punk scene—a loosely defined subculture populated by disaffected kids who range in style from skateboarders to skinheads—arrived in Amarillo by way of Interstate 40, a major thoroughfare for touring bands traveling west to Los Angeles. When punk rock exploded onto the East Coast in the late seventies, soon spreading to the Midwest and West Coast as well, seminal bands like the Clash passed through town not long afterward, bringing a whole new sound and sensibility with them. “When punk came here in the early eighties, it was exhilarating—the energy was tremendous,” recalled David Poindexter, a tattooed plumber who, at 45, is the old man of the Amarillo punk scene. “You danced until the sweat poured off you, until you were too exhausted to stand. It felt like something was finally happening here.”

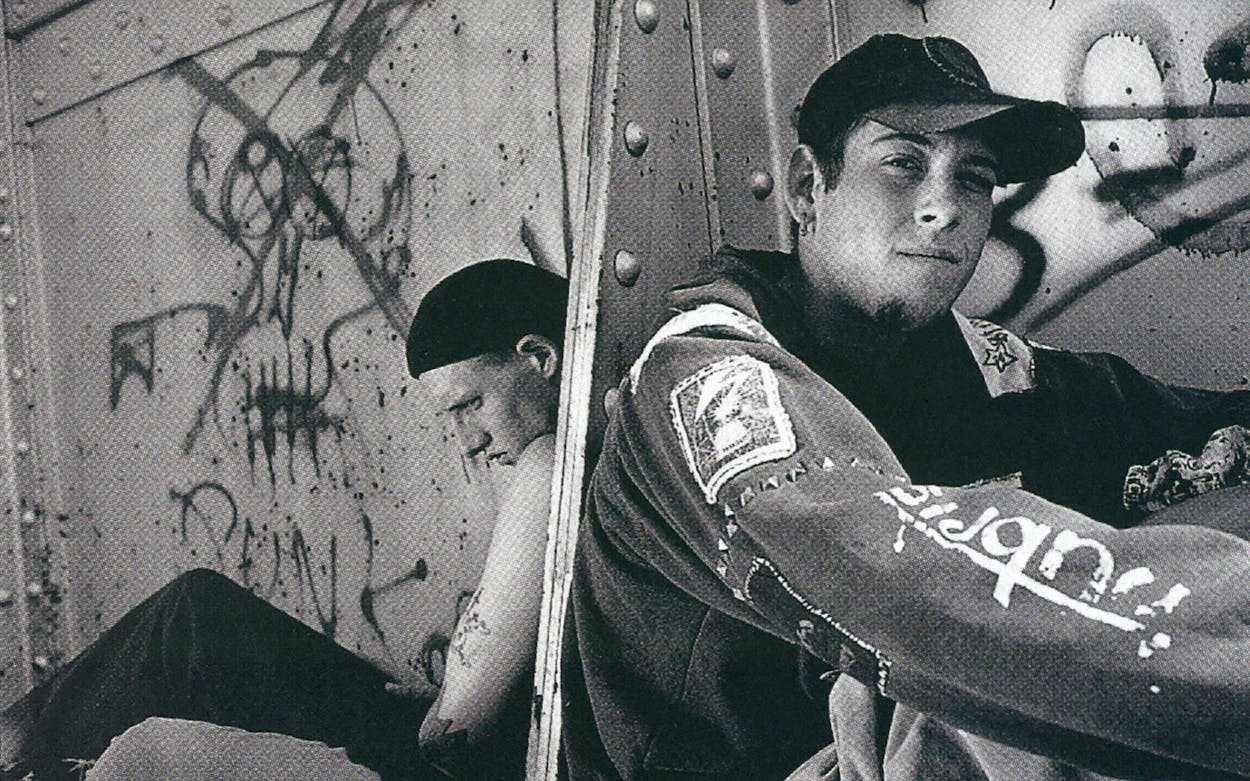

Punk’s defiant lyrics and its rejection of mainstream conventions—with its outrageous attire, anti-authoritarian attitude, and disdain for middle-class materialism—appealed to some young Amarilloans in the throes of adolescent rebellion. Though it was first and foremost about the music, which was fast and loud and often lacked any semblance of melody or virtuosity, punk also provided a ready-made aesthetic and an all-encompassing lifestyle for those who had never found their place in the world. They were not, for the most part, teenagers who excelled at school or went out for any team: They were kids who had never quite fit in, calling themselves nerds, loners, rejects, and geeks. Most were raised outside the privileged milieu of Wolflin—the older neighborhood of stately homes, well-tended lawns, and brick-paved streets where ranching families have lived for generations—and lacked the privileges others took for granted, having neither their own car nor the requisite expensive clothing. In the punk scene, they found a haven from sometimes chaotic homes and a hostile atmosphere at school. Their decision to become punks represented a shift in thinking: They were no longer outsiders by circumstance but by choice. Flaunting their differentness, they styled their hair into mohawks, covered themselves with tattoos and piercings, and wore secondhand clothes on which they scrawled slogans like “No Future.”

The most extreme-looking of the bunch are the gutter punks, a subculture within a subculture consisting of a handful of local runaways who scavenge food from dumpsters and squat in abandoned homes. Other punks view their slovenly habits and excessive drinking with contempt, arguing that they give the scene a bad name. Among their most outspoken critics in Amarillo are the Bomb City Skins, a group whose name refers to the nearby Pantex plant that once manufactured, and now disassembles, nuclear weapons. The Skins have adopted the look of traditional skinheads—pegged pants, suspenders, and work boots—but not their racist ideology; they are apolitical punks who shaved off their mohawks to be employable, and they hold down minimum-wage jobs around town. The rest of Amarillo’s punks are not as tribalized; some dress unremarkably, while others wear studded dog collars and thick black eyeliner—their entire presentation, from their green hair down to their steel-toed boots, an affront to prevailing notions of good taste.

Until recently, punks gathered at the Eighth Street House, a run-down crash pad in an overgrown, weedy lot near the center of town. It was an uninspiring place, with cheap wood paneling that was covered with graffiti and posters advertising old punk shows and a few dim fluorescent bulbs illuminating an ungodly layer of grime. Gutter punks lived there when they needed a place to stay, pooling money for rent and food; their furniture was picked from castoffs on the street, and their electricity was illegally wired into the house with jumper cables. The mood at the Eighth Street House on my first visit last summer was oppressive: A limping dog meandered along the stoop, where a boy with blue hair sipped a Schlitz and ate spaghetti out of a can, talking at length about his luckless attempts to find a job. Music blared in the background, and another boy lay disinterestedly on a beaten-up couch behind him, watching his cigarette smoke drift through the air. Among the residents there was a dead-end sort of feeling. But the place came alive at night, when a Dallas punk band played to an appreciative crowd of sixty or so teenagers, who rushed into the cavernous rec room when the thrashing cacophony of sound began to ricochet off the concrete floors. Grabbing each other by the hand, they ran toward the makeshift stage and danced in a circle to the frenetic beat—a reeling sea of boots and fists and spikes from which a few fell to the ground laughing before returning to the fray.

This was where Brian Deneke, the punk who died on Western Street, had briefly lived with his girlfriend, Jennifer Hix, a short, stocky girl with bleached-blond hair shaved on the sides and tinted pink at the edges. When I first met her at the Eighth Street House, she sat in her bedroom on a patchwork velvet bedspread, chain-smoking and absently examining her chipped blue nail polish; she wore a spiked dog collar and a faded black T-shirt that read “Conflict,” and behind her on the wall, next to an upside-down flag, rested a small sign that said, “Be Warned! The Nature of Your Oppression Is the Aesthetic of Our Anger.” Despite her forbidding, tough-girl attitude—her mouth, pierced multiple times, was often pursed determinedly into a pout—Jennifer seemed vulnerable and shy, a fragile girl behind extravagant posturing. She had first met Brian when they were kids living in the same neighborhood; when they were younger, she recalled, they used to throw eggs at each other. She had become a habitual runaway, spending time in a detention center and a work camp, but Brian later became a central figure in her turbulent life, traveling the country with her and caring for her when she had no money. The room still held remnants of his presence; in addition to the tattoo on her forearm bearing his name, his black leather jacket was hung reverently on the door—the same leather jacket that he had worn on the night he was killed.

Jennifer had been there, in the empty parking lot off of Western Street, when Brian died. The moment was still fresh in her mind, as it was for everyone who passed through the Eighth Street House. “Brian was the candle burning the fastest and brightest—people gravitated toward him,” said Dan Kelso, an older punk who once worked with him. “He was the face of the scene here. He was visible, smiling, standing tall. When he was killed, part of these kids died too.”

Brian grew up on the southwestern side of Amarillo in a working-class neighborhood of tan-colored tract homes and sun-bleached lawns—a colorless grid dotted with the occasional basketball hoop and American flag, each block one of uninspiring similarity. His parents are ordinary, hardworking people, both Kansas natives who moved to the city nearly twenty years ago when his father was transferred there by his employer. Mike Deneke is a stainless-steel-cookware salesman, a genial, heavyset man who favors plaid shirts and suspenders; his wife, Betty, a reserved woman with dark eyes, manages a photo-processing lab. It is clear upon first meeting the Denekes that they lead lives of quiet devastation; their grief, apparent in their slow gestures and downcast gazes, permeates their home with an acute sense of mourning. Their house is one of suburban propriety, with a bed of gardenias out front and, in the back yard, a mulberry tree that cradles the treehouse in which Brian and his brother, Jason, once played. In their den, an otherwise unremarkable room with an easy chair and an assortment of painted enamel butterflies and china bells in glass cases, is a black and white photo of Brian with a mohawk. “We thought that if we didn’t accept him, we would lose him,” his father said. “You get to the point where you can keep battling with your children, but you realize you’re not going to change them.”

While Jason, two years his senior, was bookish and introverted, Brian was gregarious and outspoken—a strong-willed, restless boy who rarely sat still. “He never took much of an interest in school, and he wasn’t an athletic star,” Jason recalled. “If you’re not an athlete, if you’re not a part of the culture, you’re nothing. It was difficult for Brian to fit in.” When he was thirteen, he started using a skateboard to maneuver his way around the neighborhood. He met other skaters who introduced him to punk rock, and he was soon attending local punk shows with his brother, who would become a Bomb City Skin. The hard-edged music and rebellious attitude appealed to Brian, and during his years at Crockett Middle School, he began his transformation from a Boy Scout to a skateboarder with a streak of green hair to a full-fledged punk whose hair was fashioned into a mohawk with a handful of Knox gelatin. His parents were mortified; there was constant arguing at home, and during one particularly heated confrontation, they attempted to cut Brian’s mohawk off. “He had a real strong opinion that it shouldn’t matter how he had his hair, how he dressed,” his father explained. “Even though he was right in a theoretical sense, it didn’t matter. We knew that society would judge him, and that there would be consequences.”

Brian would become one of the most controversial-looking punks in town, covering his arms with tattoos and dyeing his hair blue, piercing his nose and wearing a studded dog collar and T-shirts with slogans like “Destroy Everything.” It was not a look that went unnoticed in Amarillo. “Brian had a sense of theater about him,” recalled Marsh. “He was a smartass, and that’s why I liked him. He walked around asking for it and grinned all the way through it.” Lacking a car, Brian was a conspicuous target as he walked to and from school; after several beatings—including one that required stitches in his head—his friends nicknamed him Fist Magnet. “People tried to start fights with him wherever he went,” Jennifer said. “When people drove past him, they flipped him off or ran their mouth, calling him a freak or a faggot or a worthless piece of trash. He’d smile and say things like, ‘Oh, you’re such a big man.’ He’d point out how ignorant they were, try to broaden their horizons, and sometimes they’d listen.” For protection, he began wearing a “smiley”: a chain fastened to his belt loop with a lock on the end. In the tenth grade he responded to taunts with violence: Finally fed up with students yelling insults at him and splashing puddles on him as he walked to an Arby’s near school for lunch, he lost his temper and threw a rock at another student’s pickup. He was put on juvenile probation and promptly dropped out of Amarillo High.

Not long after, at the age of seventeen, he moved out of his parents’ house and took up residence in an apartment above a now-defunct punk club, the Egg, making ends meet by washing dishes at the Catfish Shack. Once he had scraped together a few hundred dollars, he decided to see what lay beyond Amarillo. With a stray dog in tow, he and Jennifer hitched rides up and down the East Coast and lived by their wits, collecting cans and polishing rigs at truck stops for spare change and occasionally dumpster diving for dinner. After four months on the road, Brian and Jennifer returned to Amarillo. Brian began working for Marsh in 1997, putting fake road signs—some with curious paintings on them, others with absurd sayings such as “Road Does Not End” and “Lubbock Sucks Eggs”—around town as part of a project dubbed the Dynamite Museum. Brian thrived in its carnivallike atmosphere; the sign crew rode around town in a surrealist caravan, blasting bull-fighting music out of a pink 1959 Cadillac and a Yellow Submarine–themed hearse, accompanied by a pig named Cinderella and Marsh in a top hat reading poetry. Brian worked door-to-door, trying to persuade Amarilloans to place Dynamite Museum signs in their front yard, and his brash charm worked on even the most resistant of adults. “He looked bizarre, but he could walk toward people with his hand out, grinning, and they would like him before he got to their front door,” Marsh explained. “I called him Sunshine. He was boisterous, optimistic, fun—so Sunshine just stuck.”

Brian assumed a larger-than-life stature among the punks, bringing traveling bands to town with the money he earned through the Dynamite Museum and making the Eighth Street House a refuge for kids who had nowhere else to go, providing them with food and a place to sleep. “Brian’s main goal, and he had saved a whole lot of money for it, was to start an all-ages place for bands, poetry, art, theater,” said Brady Clark, a former Bomb City Skin. “He wanted to have a place where kids could hang out, be in their own element, and not get harassed by a bunch of drunk rednecks. He wanted to give everyone something constructive to do with their free time.”

Brian could have used something constructive himself. In his own free time, he drank heavily; his blood alcohol level on the night he died was .18 percent, nearly twice the legal limit at the time. That night, he had spent the previous few hours at his brother Jason’s house, listening to records and drinking beer, before deciding to drive up to Western Street. Whatever Brian’s motivations were when he joined the fighting—whether it was out of loyalty, vengeance, or drunken bravado—Jennifer is sure that he didn’t expect to die. “I remember after he was hit, there was a cheer,” she said flatly, steeling herself against the heartache of the memory. “We ran to him as soon as he went down. He was trying to talk, but there was too much blood coming out of his mouth. Jason put his arms around him and held him while he died.”

As the Cadillac sped away from Western Street, Elise Thompson sat in the back seat in stunned silence, her panic slowly giving way to a profound sense of dread. Her mind reeled; the enormity of what had happened seemed impossible to grasp, but she knew, as the car headed down the freeway toward home, that the boy on the pavement was dead. Dustin Camp raced toward Wolflin, turning down one of its wide streets before breaking the silence. “Y’all don’t have to go down with me,” he offered, his voice filled with alarm. “I’ll tell them you weren’t in the car.” Rob Mansfield nodded solemnly from the front seat, agreeing that perhaps that would be best. “But we were in the car,” Elise said firmly. “Nancy,” Rob urged her, calling her by her first name, “I don’t think you understand how serious this is.” Upon hearing his friend’s assessment of the situation, Dustin lost his composure and broke into choking sobs, banging his head repeatedly against the steering wheel.

It was not the face he usually presented to the world. Relentlessly upbeat, he often wore a confident grin, his close-cropped blond hair framing a boyish face. “Dustin has a million-dollar smile and a sense of humor that’s contagious,” said a family friend. “He laughs with his whole body. When he enters a room, the mood lightens, people smile.” In the locker room at Tascosa High he regularly ribbed other players as they suited up, keeping them in stitches before the game and at halftime. “He used to joke around in class a lot and make everybody crack up,” remembered his friend Jesse Sierra. “At dances, he danced real wild. He’s laid-back, never serious.” When football season was over, he spent his afternoons lifting weights and his weekends mountain biking in nearby Palo Duro Canyon; during the summers, he worked at the auto repair shop that his parents owned, fixing cars with his father.

Football was an all-consuming passion for Dustin (who declined to be interviewed for this story, as did his parents), though he was not blessed with the physique for stardom. He was slightly built—a shortcoming he worked hard to overcome, eating peanut butter and jelly sandwiches between meals to bulk up and lifting weights with a determined intensity. “He wasn’t anyone we noticed initially,” recalled Tascosa High JV football coach Alan Hunnicutt, “but his desire to play was 110 percent.” The Camps were enthusiastic supporters, attending every game of the season and sounding an air horn whenever the team scored a touchdown. But by his junior year, Dustin was still playing JV football while many of his friends—including Rob—played varsity and excelled at the game. If he felt any frustration, he deflected it with jibes and jokes, sitting with the varsity team at lunch and trading wisecracks with them in the weight room.

Dustin knew well what it meant to be on the outside looking in: Though he was well regarded by the teenagers in Tascosa High’s ruling elite, he was not one of them. He was from a family of average means, an inescapable fact that set him apart from the old-money crowd. His Cadillac was nearly fifteen years old, and his parents’ house, though in Wolflin, sat on its edge, one block from a lower-income part of town. Yet rather than rejecting a world to which he could never fully belong—as had the punks, whom he and his friends scorned—he embraced it. Standing at the fringes of the in crowd, he perhaps longed for a sense of identity; by distancing himself from the “freaks,” he and his friends could delineate their own social standing within Tascosa’s stratified society, a place where each clique eyed the others with equal suspicion. Such antagonisms were often fueled as much by drinking as by any real aversion to one another; in the hours before Brian’s death, Dustin drank a few beers with a friend, and in his Cadillac was a partially empty eighteen pack of beer and a nearly empty bottle of whiskey left over from the week before. Of course, the night that Brian died was unlike any other. “It was pandemonium,” said one parent. “One of Dustin’s friends had a concussion; another had his head laid open with a chain. A few boys went to the hospital, and the rest came home screaming.”

Dustin had returned home that evening for a restless night’s sleep, but Elise and Rob—after a tearful discussion—decided to wake their parents and drive down to the police station. Their accounts of what had happened made for damning evidence against their friend: At dawn, police officers arrived at Dustin’s house and arrested him on a charge of murder. He would first claim that he had been alone in his car; he would also say that he had been trying to help a friend who was being beaten by Brian and that Brian had fallen under the wheels of his Cadillac after slipping on ice. “Dustin’s fault that night lay in intimidation and fear, not hatred, but what he did was still wrong,” Elise observed. “A lot of people tried to defend him, but you cannot defend what he did.” The event devastated Elise, who went into a severe depression, unable to get out of bed during the weeks that followed. “I didn’t feel like I should be alive,” she said. “I felt so guilty. I ran those few moments over and over again in my mind, trying to figure out what I could have done different. People tried to comfort me, but they didn’t understand.”

This May, during Tascosa High’s graduation ceremonies, Elise startled her fellow students by delivering an emotional valedictorian speech about the night of December 12, 1997. “On that evening, a boy lost his life and with him a part of many people died,” she announced to the assembled crowd of five thousand, while some students shifted uncomfortably in their chairs. “Nothing else I have experienced has so greatly molded who I am and what I think. I hope its message can penetrate your heart.” Describing how the fatal fight was waged between “two groups of people who wore different types of clothes,” she urged her classmates to rethink their own prejudices toward one another. “So I challenge you and me, all of us, to break through the stereotypes with which you may have been raised. I challenge each one of us to see the art, the beauty of humanity, in others.”

The trial began on an uncommonly hot, windless morning during the last week in August this year at the Potter County Courts Building, a monolithic building of concrete and granite that seems out of place amid the classic limestone facades of downtown Amarillo. On the left side of the aisle that divided Judge Abe Lopez’s courtroom lay a familiar tableau of suburban life: Broad-shouldered boys in khakis and button-down dress shirts, accompanied by their girlfriends; Mike Camp and his wife, Debbie, who greeted their son’s friends warmly; a pastor from the First Presbyterian Church; and several older, smartly dressed relatives whose pleasantries and courteous manners were reminiscent of a Sunday afternoon church function. Across the aisle sat Mike and Betty Deneke, holding hands in silence, and behind them were three rows of punks: a ragtag bunch that, despite having removed their piercings and wallet chains and dog collars for the benefit of a metal detector, looked distinctly out of place in the formality of a courtroom. Dustin sat at the defense table with his back to them all, his hands folded neatly. He would register little emotion for the duration of the seven-day trial, though he occasionally flushed with embarrassment when his friends took the stand.

“We believe that the evidence will convince you beyond a reasonable doubt,” assistant district attorney John Coyle announced to the jury, his arm outstretched as he pointed accusingly at the defendant, “that this was not an accident, that this was not justified, and that the defendant intentionally and knowingly murdered Brian Deneke.” The prosecution would present compelling evidence against Dustin: He had never applied his brakes or turned his steering wheel as his Cadillac had approached Brian, he had fled the scene of the crime, and he had lied to the police. But it was defense attorney Warren Clark who set the tone for the proceedings when he put the punks—and Brian’s character—on trial, transforming the murder case into a wholesale condemnation of the punk scene. “Ladies and gentlemen,” began Clark, a persuasive orator who favors dark suits and theatrical flourishes, “this is not a case of diversity, or tolerance, or judging people by the way they dress. This case is about a gang of young men who choose a lifestyle designed to intimidate those around them, to challenge authority, and to provoke a reaction from others.” Clark contended that when the punks brought bats and chains with them to Western Street, “a conspiracy was put into play . . . to kill and maim these high school students.” His client, he argued, had no other option but to protect the life of his friend, whom he suggested Brian was beating. “[Dustin] had no time to think or ponder. He had to take immediate action and he took it. And if he had to live it over again,” said Clark meaningfully, fixing his gaze on the jury, “he would do it again.”

The prosecution would spend much of its time chipping away at Clark’s assertions: For instance, testimony suggested that it was another boy, John King, not Brian Deneke, who had struck Dustin’s friend in the parking lot. Additionally, Dustin’s cavalier comment—“I’m a ninja in my Caddy”—hardly reflected the state of mind of a panicked teenager trying to save a friend’s life. The jury was riveted by certain moments in the state’s case, as when Jason Deneke described in a low, halting voice how his brother had died in his arms, while those on the punk side of the courtroom openly wept. The trial, however, ultimately belonged to the defense, which sought to establish that Brian was a belligerent teenager prone to violence who was therefore an imminent threat to Dustin and his friends. “I had never seen eyes so cold and dark,” testified Brian’s former Boy Scout troop leader, Tom Scherlen, about an argument they had over a skateboard when Brian was thirteen years old. “He told me that I was a son of a bitch and that he didn’t need to be in my troop anyway.” Police officer Jeff Stephenson, who had arrested Brian for disorderly conduct when he was sixteen, recounted how the teenager had shouted obscenities when police officers tried to clear the street outside a busy punk club. Another officer, at the request of the defense, held up for the jury each item of clothing that Brian had worn on the night of the fight—camouflage pants, combat boots, chains, and a ratty shirt—as well as a photograph of him with a mohawk.

Though such evidence had little to do with the case against Dustin, it served as a powerful reminder to the jury that Brian was a very different sort of teenager than the blond, all-American eighteen-year-old who sat politely before them at the defense table. Dustin had shed the bulky muscularity of his football days, and his sober countenance suggested that he was no longer the class cutup but a responsible teenager on the verge of adulthood. He would not take the stand in his own defense, but his very presence in the courtroom—with his family and friends assembled behind him, evoking a reassuring portrait of middle-class values—spoke louder than any words he could have delivered on his own behalf. It was a point Clark sought to drive home in his vitriolic closing argument, in which he alluded to the “goons” and “thugs” sitting on the opposite side of the courtroom. “What Dustin Camp faced out there,” he thundered, “was a mean drunk with a weapon. . . . Somewhere in the infinite processes that make a boy into a man, something happened to Brian Deneke . . . His manner of death was unfortunately the end result of his choices over the last six years prior to his death. You could even argue that he was destined to die the way he did. He was a violent individual. And it took violence on Dustin’s part, Dustin Camp’s part, to put an end to further violence and to save an innocent life.” Clark paused, then pointed toward his client as his voice reached a feverish pitch. “Let this boy go home, and restore him to his family,” he implored, “because he did the right thing.”

After several hours of deliberation, the jury convicted Dustin not of murder, as the prosecution had hoped, but of manslaughter—deciding, in effect, that he had acted recklessly rather than with intent. Both sides seemed equally astonished by the verdict, but they reserved their opinions until the conclusion of the sentencing phase. Manslaughter carries a two- to twenty-year prison sentence, although the jury was also given the option of awarding Dustin probation since he had no criminal record. The defense presented a series of character witnesses who supported leniency: Dustin’s former football coach, who praised him; teachers who described his diligence in the classroom; a friend of his parents’ who declared that “he would make his family, his church, and his community proud”; and the pastor, who described how the Camps had “modeled the godly life before their son.” As witness after witness took the stand to extol his virtues, it was easy to lose sight of the fact that the clean-cut boy behind the defense table had, by taking a life, trespassed the most basic of moral codes. But the image of a now repentant teenager who had fallen from grace was a resonant one, and the jury listened intently when Dustin took the stand to apologize to the Denekes. “It’s a tragic deal that happened, and it shouldn’t have happened,” he declared from the witness box. “After all the pain and agony my friends and family have been through, the Deneke family have been through, I would have gotten out of that car. If I had gotten beaten down with a bat, it would have been better than all this.”

Coyle rose from his chair at the conclusion of the defense’s closing argument and launched into a passionate plea for punishment. At 31, he was an exceptionally young prosecutor, with a round, earnest face that had registered both shock and outrage during the course of the trial; when the medical examiner had described Brian’s injuries—he had been conscious when he was dragged under the wheels of the Cadillac, its impact so severe that his collarbone had been torn free from his shoulder—Coyle had looked visibly shaken. Now he stood before the jury, beseeching them to see the grander purpose behind their decision. “Our young people, on both sides of this aisle in our community . . . need to be told by the twelve of you that what you do carries consequences . . . whoever you are, no matter what you look like, no matter how you dress,” he said in a solemn, deliberate voice. “I don’t expect you to enjoy sending this young man to prison, however long you send him for. I expect you to do it with a tear in your eye and your heart in your throat. . . . President John Kennedy said we do things not because they are easy, but because they are hard. I ask you to do the hard thing. I ask you to send a message to this community that all young people, all of them, will suffer the consequences of their actions, and that you are holding Dustin Camp unconditionally responsible for the death of Brian Deneke.”

The twelve jurors, however, were not swayed; after deliberating for nearly three hours, they sentenced Dustin to ten years’ probation and a $10,000 fine he will not have to pay if he stays on his best behavior. The anguish of those on the right side of the courtroom was tangible; Mike Deneke’s shoulders sank in resigned defeat, his face ashen. Behind him, three rows of teenagers gripped one another’s hands tightly, choking back tears. Coyle stared miserably at the jurors before him, as Dustin turned from the defense table, nodding courteously at his attorney and his parents, before walking out of the courtroom and through the courthouse doors into the bright afternoon sunshine.

News of the sentence, which was broadcast live from the courthouse late that afternoon, stunned many residents of Amarillo, spurring a deluge of phone calls to local TV stations and stirring debate across the city. Parents took to the airwaves to voice their outrage about the message that such a verdict sent to teenagers in the community, while others simply shook their head in dismay, expressing astonishment that someone convicted of manslaughter would never spend a night in jail. At one hastily organized community meeting at a Unitarian church, several attendees openly wept, and by the time the ten o’clock news aired that evening, anger had reached a fever pitch. “If all you get for murdering someone with your car is ten years’ probation with a felony-free record,” wrote one incensed television viewer in an e-mail that was read on the air, “then I can only ask Mister Camp not to let me see him walking around.” Such bitterness did not wane as the days passed: An Amarillo Globe-News poll revealed that 74 percent of respondents believed that the punishment did not fit the crime, and emotions ran so high that Judge Lopez sealed the list of the jurors’ names out of concern for their safety.

There was little doubt about the message sent by the twelve men and women who sat in judgment that day. It was what the punks felt they knew all along: Teenagers deemed “good kids” could enjoy a sanctioned sort of rambunctiousness in Amarillo without fear of punishment, since a boys-will-be-boys attitude would pardon even their most egregious behavior. Such indulgences, however, did not apply to those who stood on the margins. Had the roles been reversed—if a football player had lost his life that night at the hands of a punk—did anyone believe that a jury would have rendered the same verdict? For punks, teenagers who had never had faith in the system, the outcome of the trial reaffirmed their worst fears, and revealed the true costs of a social order in which some boys are valued more than others.

Many punks, frustrated by the harassment they had received even in the months after the killing, had drifted away from the scene, shaving off their mohawks and dressing in darker, muted clothes. There was, among these teenagers, a deep sense of loss: The Eighth Street House is now uninhabited, a remnant of another time, and punk shows are sparsely attended. Many spoke of moving on—to Austin, Dallas, maybe west to California. Anywhere, they said, where they might feel more at ease. Though they were comforted by the community’s support after the trial, many punks felt that the outrage of adults had arrived too late: Where, they wondered, had the concern of teachers, parents, and even the police been before the verdict became front-page news?

Their questions would go unanswered. Despite a trial that had rocked this city to its core, little had changed: On my last night in Amarillo, I spotted two punks loping along Western Street toward an empty parking lot, their skateboards tucked under their arms. A black pickup stopped at a red light; both its teenage driver and passenger, straining for a better view, rolled down their windows and stared intently at the punks who made their way up the boulevard. As the boys drove off, you could hear—just barely—gales of laughter and a string of obscenities over the squeal of car wheels.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- High School

- Crime

- Amarillo