One way to get a fat lip these days is to attempt to define what country music is or what it has become. Even those with credentials as something close to true experts—the pickers and sangers, the song poets, the critics—cannot agree on what has the better claim to legitimacy.

To state the decree of one’s own limited expertise: I listen to country music with a veteran ear, can carry a tune provided the bucket’s big enough, pick guitar as if wearing Boss Walloper work gloves over a pair of concrete hands and only in the absence of witnesses. I am your average barstool expert, a foot-tapper and sing-alonger and guzzler of long-neck beers, and we are worth about six cents the carload in the adjudicating of musical disputes.

Ray Price or Eddy Arnold, with all those syrupy violins singing behind them, do not necessarily set my teeth on edge, though my friend Buck Ramsey of Amarillo—who chords a little guitar when there are no musicians in the room—never fails to howl how they are frauds, if not felons, for their crimes against traditional country licks. Though Olivia Newton-John sounds as though she were shifting a mouthful of plum pudding, and Loretta Lynn as if she just rode into town on a load of turkeys, even they have their respective partisans among experts: each won plaques and scrolls this year.

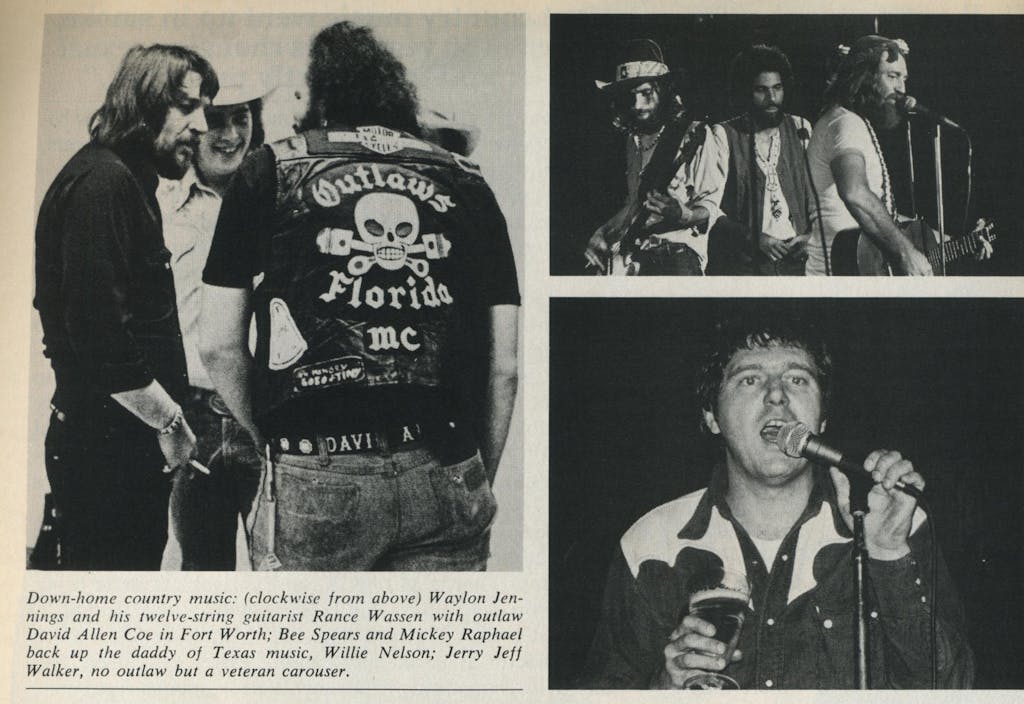

I can weep along or cheer when Ernest Tubb walks the floor over you, when Kinky Friedman pays tribute to that asshole from El Paso, when Patsy Cline falls to pieces, or when Buck Owens and his Nasal Passages celebrate being together again. I like Waylon and Willie—but I also respond to the corny likes of Red Foley, Roy Clark, Cowboy Copas. This, I like to think, is not so much because of a lack of character as because of catholic tastes developed over more than forty years of country music exposure. We accomplish little more than wasted energies in debating whether Jerry Jeff Walker or Dolly Parton deserves the larger accolades when judged on more than their chest measurements. For the fact is that all of these, and others—from Fiddlin’ John Carson, who in 1923 recorded the first “hillbilly” song, “The Little Old Log Cabin in the Lane,” to the newest would-be cosmic cowboy looking for his big break in Austin—have been, or are, part of an ongoing evolutionary process.

The continuity of country music is best appreciated when one considers its lyrics, rather than its diversities in singing styles or instrumental licks. Simply put, content is more important than melodies or rhythms. The theory is offered that should all our national archives except country music lyrics somehow go up in smoke, then what has happened to America within the last fifty years at least—its shift from an agrarian to an urbanized society, its changing sexual mores, its growing sophistication as well as its growing madness—would still be almost perfectly preserved. With one notable exception—that of our ugly racial prejudices and the resultant upheavals—our country poets, perhaps even more than our novelists, have written from the gut of those basic preoccupations of farmers and housewives and working stiffs. The larger human themes are there—the crazy convolutions of the human heart as it encounters new places and homesickness and poverty and unrequited love and other pains leading to excessive applications of whiskey or, lately, dope. Too bad Faulkner couldn’t strum.

A little history may be in order. Country music was born in the early Twenties of a mixture of gospel airs, folk songs, English ballads, and soul (or “race”) music, but this native American art form soon came to be associated with the Great Depression—the first universal experience to be shared after the country music genre came into its own. We rootless or ruined children of the Thirties identified with the drifting hobo or a silver-haired daddy left somewhere behind. Our songs commemorated the people and places we knew: whiskey widows, sisters menaced by the wicked cities of the American hinterland, deep mines, and company stores; they recounted our pitifully few conquests and reflected our impoverished and isolated lives. The music boiled in our blood the week around: through the hot work of the grain harvest, in the fearful soul-searching of midweek prayer meetings, up and down endless rows as we picked cotton nobody had the money to take off our hands. In our unpainted rural farmhouse in Eastland County, Texas—where one generation had died, one grew to adulthood, and still another was born—that music from our old Zenith battery radio reaffirmed our troubles and refurbished our dreams.

It was no accident that in 1929, the year the Great Depression began, Bob Miller and Emma Dermer wrote a country hit called “’Leven Cent Cotton and Forty Cent Meat.”

‘Leven cent cotton, forty cent meat.

How in the world can a poor man eat? . . .

No corn in the crib, no chicks in the yard

No meat in the smokehouse, no tubs full of lard

No cream in the pitcher, no honey in the mug

No butter on the table, no ‘lasses in the jug . . .

‘Leven cent cotton, ten dollar pants.

Who in the world has got a chance?

On Saturday nights, at the traditional stomps to be found along the creek banks—complete with fruit jar whiskey and random fistfights—local Mozarts of the fiddle, guitar, and mandolin, on sundown leave from the fields or the broom factory over in Cisco, strummed and cried the songs of the period. These were a mixture of the new and the old, some dating back before the turn of the century: “Papa’s Billy Goat.” “Old Joe Clark.” “Buffalo Gals.” “The Farmer Is the Man that Feeds Them All.” “Cotton-eyed Joe.” “When the Wagon Was New.” “Wreck of the Old 97.” “Lamp Lighting Time in the Valley.” “Waitin’ for a Train.” “May I Sleep in Your Barn Tonight, Mister?” “Put My Little Shoes Away.” “Mother, the Queen of My Heart.” “Little Rosewood Casket.” Not a touch there of modernity. There were many songs lamenting infant mortality and others warning against drinking, gambling, and simplistic fundamentalist sins thought to lead directly to Huntsville’s red brick walls and thence to a coal-shoveling Hell.

In those days before erring public officials emerged from minimum-security prisons with six-figure book contracts to relate their sordid experiences, or before the David Allen Coes or the Merle Haggards exploited their outlaw days in song, a prison past automatically constituted a permanent disgrace. One of my earliest morality lectures came not from Deuteronomy but from a song in which a selfless felon advised his sweetheart against waiting for him because “I’ll always be an ex-convict and branded wherever I go.” My father, whisker-stubbed and solemn as Job, spoke in the circle of pale yellow light from a kerosene lamp at his elbow: “Son, there’s a heap of truth in that song. . .”

One favorite, variously known as “Mother Was a Lady” or “Brother Jack,” reflected the rural conviction that no matter what loose liberties one might hope to take with another man’s sister, one’s own sister remained pure even past the wedding vows and possibly the birth of twins. The sweet sister in “Brother Jack” is a waitress in the wicked city; one night she is tormented by ruffians until “her cheeks were blushing red.” The offended sister then sings:

My mother was a lady

like yours, you would allow.

And you may have a sister

who needs protection now.

I’ve come to this great city

to find my brother dear.

You wouldn’t dare insult me, sir

if Brother Jack were here.

All ends well: one of the ruffians, a good ol’ boy who’d merely had a bit too much demon rum, is so ashamed of his group’s conduct that he offers to take the sweet sister to her long-lost Brother Jack—as his bride. Well sir, they’d hoot you right off the stage should you offer such a number now—the song, after all, was written in 1896—in a time when many brothers might ask their sisters to do a little light pimping for them among their comely friends, or vice versa. In that long ago, however, one honored one’s women as well as one’s flag, and the family was sacred above casual carnal lusts. Just recently, driving the dusty backroads near the old family farm where I spent most of my first thirteen years, I experienced cultural disorientation by hearing over an Abilene radio station a country song in which a new bride invites her former lover to call while hubby’s away; she vows that “the door is always open, and the lights on in the hall.” Once one might have been quite routinely shot dead for accepting that invitation in much of America—and, in fact, in 1900 my paternal grandfather was. The offended Eastland County farmer who did him in by shotgun was a Christian gentleman, however, and permitted Morris Miles King both to clothe himself and to say his final prayers before being dispatched.

Bill C. Malone, in his Country Music, U.S.A, writes of the time when many country songs contained a highly confessional quality and tones of self-flagellation: “A person sometimes sings about ‘poor old mother at home’ because he’s neglected her; he ran off and left his parents and went out to seek his fortune—to do his own thing—and a sense of guilt set in. The best way to assuage that guilt is to make up a song about ‘poor old mother.’ You don’t do anything for mama in making up such a song, but you do rid yourself of the guilt.” This sense of guilt certainly is prevalent in “That Silver-haired Daddy of Mine”:

If I could recall all the heartaches

Dear old Daddy I caused you to bear.

If I could erase those lines from your face

And bring back the gold to your hair.

If God would but grant me the power

Just to turn back the pages of time

I’d give all I own if I could but atone

To that silver-haired Daddy of mine.

You won’t find many poor old ma or dear old dad songs anymore. Members of a long-mobile and shifting society no longer feel guilt in pulling up their shallow roots and going out to seek their slices of life’s pie. People still write songs of home and family, sure: Loretta Lynn’s “Coal Miner’s Daughter,” Dolly Parton’s “In the Good Old Days when Times Were Bad,” Johnny Cash’s “Picking Time,” Merle Haggard’s, “Mama Tried.” For the most part, however, these are songs of nostalgia, not of repentance. They even contain notes of relief at having escaped the farm or the factory. Parton: “No amount of money could buy from me/ memories that I have of then./ No amount of money could pay me/ to go back and live through it again.”

Among Progressive country or “redneck rock” poets, even mother isn’t to be taken seriously anymore. David Allen Coe has made a hit of Steve Goodman’s “You Never Even Called Me By My Name,” in which the last verse pokes fun at a mother who just got out of prison and gets hit “by a damned old train.” Ray Wylie Hubbard’s “Up Against the Wall Redneck” puts to shame all earlier mild protests against Momism:

Up against the wall Redneck Mother

Mother who has raised a son so well.

He’s thirty-four and drinking in a honky-tonk

Kickin’ hippies’ asses and raising hell.

“Wreck on the Highway,” popularized by Roy Acuff, was one of the first songs to note the impact—not always for good—of the automobile. It was composed in 1932, the year Ford introduced the V-8 engine. There is much of transition in the song, a sense not only of dangerous new forces to threaten us in the technological age but also a primitive fear of losing old values:

Who did you say it was brother?

Who was it fell by the way?

When whiskey and blood ran together

Did you hear anyone pray?

I didn’t hear nobody pray, dear brother.

I didn’t hear nobody pray.

I heard the crash on the highway

But I didn’t hear nobody pray.

The car—and especially the truck—has since figured prominently in hundreds of country songs. Indeed, truck-driving songs long ago became a genre into themselves. Realizing that much of the radio audience was composed of lonesome teamsters, songwriters were quick to glorify them, their myths, and their legends. Ghost drivers or ghost riders constituted a favorite theme: truckers who gave lifts to hitchhikers and were subsequently proved to have been killed so many years ago that very night. There also was an outpouring of songs wherein God or the Lord or other benign spirits safely passed truckers through blizzards, rock slides, or other road hazards.

Ironically, truck drivers recently have become so addicted to the more personal intimacies of Citizens Band radio—where they may broadcast in rough imitation of the commercial disc jockey talking to them out of Cincinnati or Omaha—that they pay far less attention to commercial stations. Country poets, however—true to the tradition of recording cultural changes and hopeful of big royalties should they artfully exploit the latest craze—are crashing the Top 40 charts by writing of outlaw CB caravans, lawmen who trap speeders through misrepresenting themselves on the CB band, of romances owing their beginning to CB radio contacts, and of a crippled boy who uses for his handle “Teddy Bear.” Within the past week, I’ve heard seven CB-inspired songs on a New York country station. All were simply terrible.

The train enjoyed a long run in country music and, though the day of the train is over, the train songs are not. Trains have provided handy metaphors in such songs as “Life’s Railway to Heaven,” from the distant past, to Kinky Friedman’s “Silver Eagle Express,” which is used for the hailing of memories and dreams. Jimmie Rodgers, known as the “Singing Brakeman” and often billed as the father of country music, almost wore out the train as subject matter—as did one Marion T. Slaughter, another Texan, who took the names of two Lone Star State towns to become famed as Vernon Dalhart. Early rain songs were about wayward men sleeping new water tanks while dodging heartless railroad dicks in hopes of flagging a freight bound for some vague better place. In country songs trains were ridden by orphans in search of their roots, soldiers bound for battle, sons returning for funerals, misfortunates being transported to prison. Trains were almost universally the inspiration for songs of melancholy—perhaps it had something to do with that forlorn whistle—with only a few, such as “Fireball Mail” or “Wabash Cannonball,” stressing that certain exuberance to be found in speed and its kindred exhilarations. A few songs celebrated grinding wrecks or such glorious heroes as Casey Jones, who stayed with their doomed locomotives to the fatal last, and stout-hearted men (John Henry) who drove the steel over which the trains rumbled and roared and caught the fancy of a young and growing nation.

So quickly have trains receded into the cultural past, however, that Guy Clark’s “Texas—1947,” celebrating when the first diesel came through a small Texas town, now qualifies as pure nostalgia. It was a big event indeed when the first streamliners came through not long after the end of World War II, causing schools to turn out and old men to leave their dominoes; no one then knew how quickly the new supertrains would be rendered obsolete by the burgeoning airline industry. Clark told it this way:

Look out, here she comes, she’s comin’.

Look out, there she goes, she’s gone.

Screaming straight through Texas

like a mad dog cyclone.

Lord, she never even stopped

But she left fifty or sixty people

still sittin’ on their cars

Wonderin’ what it’s coming to

and how it got this far.

What it was coming to was the airplane—and quickly. Somehow, though, the airplane has yet to catch on in country music as a romantic vehicle. Maybe it is all that tasteless food or the sense of isolation in a pastel cocoon that Norman Mailer or somebody has compared to the nursery. At any rate, the airplane has been confined to a supporting role in the making of folk heroes (“Amelia Earhart’s Last Flight” or “The Lone Eagle” in celebration of Lucky Lindy), the machine being strictly secondary to those human units who mastered it or went down in flames. It is given only brief, perfunctory mention in war songs: the renowned combat pilor of World War II, Colin Kelly, is lavishly celebrated in the ballad bearing his name, but his plane isn’t memorialized. If anybody wrote a song honoring the Enola Gay, which dropped The Bomb on Hiroshima, it mercifully has escaped my notice.

Similarly, Willie Nelson in “Bloody Mary Morning” wryly takes note of modern air transportation while flying down to Houston, but forgetting her is the real reason for the flight—and the song.

Well our golden jet is airborne as

Flight 50 cuts a path across the morning sky

And a voice comes through the speaker,

Reassuring us flight 50 is the way to fly.

And our hostess takes our order,

Coffee tea or something stronger,

To start off the day.

Well it’s a Bloody Mary morning

‘Cause I’m leavin’ Baby somewhere in L.A.

“Biggest Airport in the World,” was inevitable, with songwriters rushing to capitalize on it almost as rapidly has Hollywood jumped on the slogan “Remember Pearl Harbor” (more than half a dozen motion picture companies had filed their claims by mid-December 1941). The airport song, however, isn’t really about the Dallas-Fort Worth Airport or about airplanes. It’s a spoof about a good ol’ boy who, stood up by a painted lady who’d promised to fly with him to El Paso and get married in Mexico, sings of how the poor darling must be “lost and crying in the biggest airport in the world.” Airplanes, somehow, are just not taken seriously by our country poets.

Songs of homesickness retain a high degree of popularity. There are literally thousands, mourning the loss of those old cotton fields back home, of the lone prairie, of those special nooks and crannies of one’s beginnings. One wonders how long this can survive: how will the suburban-based songwriters of tomorrow, today growing up in bald settlements with no history, find anything to lament in their pasts? Only in recent years have country artists registered the disillusions of urbanization: “New York City Blues,” bemoaning how cold-hearted are the people who populate the place, and “Streets of Baltimore”—recounting how a tired factory worker is dragged from bar to club by a wife whose head has been turned by the big city. But these must take a backseat to “Detroit City.” The latter is the saga of a country boy stuck on an automobile assembly line, and it spoke to the heart of every Clem or Rube sick of walking on concrete and bathing in neon. It’s full of the loss of great expectations, of a rootless and empty life, of people attempting to keep up a front:

Home folks think I’m big in Detroit City

From the letters that I write they think I’m fine.

But by day I make the cars, by night I make the bars.

If only they could read between the lines.

I wanna go home, I wanna go home.

Oh, how I wanna go home.

Until the recent advent of the redneck rockers, or the so-called “outlaws” or “cosmic cowboys,” country songs were notorious for their political conservatism. Many expressed sentiments that might have come straight from the bar talk to be found in Midland’s Petroleum Club. Tom T. Hall lamented, “Too many do-gooders and not enough hard-working men.” Hippies, longhairs, dopers, and peaceniks caught it two times from Merle Haggard—in “Okie from Muskogee” and in “The Fighting Side of Me.” Guy Drake’s “Welfare Cadillac” expressed the malice indigenous to those who see the unfortunate as leeches or con men:

I know the place ain’t much,

But I sure don’t pay no rent.

I get a check the first of every month

From the federal government.

Every Wednesday I get commodities

Sometimes four or five sacks.

Pick ‘em up down at the welfare office

In my welfare Cadillac.

Roy Acuff, twice a conservative Republican candidate for governor of Tennessee, checked in by knocking old-age pensions:

When her old-age pension check

Comes to her door

Dear old grandma won’t be

Lonesome anymore.

She’ll be waiting at the gate.

Every night she’ll have a date

When her old-age pension check

Comes to our door. . .

There are more antifeminist songs than not. Kinky Friedman and the Texas Jewboys recommend that you should “Get Your Biscuits in the Oven and Your Buns in Bed”; Bob Luman reckons that “Lonely Women Make Good Lovers”; Tammy Wynette advises the ladies to “Stand by Your Man” and Tompall Glaser has offered Shel Silverstein’s “Put Another Log on the Fire” in which the male chauvinist orders his girlfriend to perform errands including fixing a flat tire, washing his socks, and patching his old blue jeans—“and then come and tell me why you’re leaving me.” Loretta Lynn, of all people, has fired back at the chauvinists with her mild “One’s on the Way” (about the dissatisfactions of a pregnant house-wife) and her more direct “The Pill.” Even Tammy Wynette, playing the other side of the street for a change, warns her wandering man in “Your Good Girl’s Gonna Go Bad”:

I’m gonna be the swingingest swinger you ever had

If you like ‘em powdered up, painted up, then you oughta be glad.

‘Cause your good girl’s gonna be bad.

The popularity of our wars (or the lack of popularity in recent years) has been faithfully reflected in country music. Only “The Ballad of the Green Berets” made it as a pro-war song during the Vietnam misadventure, and it was written in 1963 before people began to realize what a quagmire was in the making. There were lesser, minor pro-war songs later along in that war—but, significantly, the public did not take to them. Nor did Korea songs achieve popularity. “A Dear John Letter,” in 1953, told of a soldier “overseas in battle” who received a letter from the girl back home saying she’s soon to wed another—but it didn’t even refer to Korea specifically. Floyd Tillman’s “Cold War,” while using the term as a metaphor, is just another he-she song having nothing to do with formal battlefields. Unless memory fails, no songwriters saw glory in the battle of “Frozen Chosin” or tried to make a folk hero out of the captured General Dean; nor did they lash out at the 21 American “turncoats” who originally refused repatriation. In war, as with the racial troubles of America, country songwriters have followed the policy of saying nothing at all if they couldn’t say something good.

World War II, however, was a “happy” war. Though I’ve since read historians who made me aware of a certain body of opposition to that venture, I was unaware of anything but an enthusiastic and patriotic approval at the time. This universality of opinion was registered in the country music of the period. Indeed, before the firing of the first American shot, World War II began to be propagandized with a ditty entitled “I’ll Be Back in a Year Little Darlin’.” The song was in response to the peacetime draft, which passed the House of Representatives in 1940 by but a single vote. Young eligibles would receive a year of military training, then be discharged to stand by as citizen-soldiers in the event of hostilities:

I’ll be back in a year little darlin’.

Uncle Sam has called and I must go

I’ll be back never fear little darlin’.

You’ll be proud of your soldier boy I know.

I’ll do my best each day for the good ol’ USA

And I’ll keep Old Glory wavin’ high.

I’ll be back in a year little darlin’.

Don’t you worry darlin’, don’t you cry.

Literally hundreds of country songs came out of World War II. Among the most popular: Floyd Tillman’s “Each Night at Nine,” in which he asks his love to remember him faithfully at that hour each night; Ernest Tubb’s treatment of “Filipino Baby” (about leaving a sweet dusky island maiden behind) and its cousin “Fraulein” (leaving a German beauty behind); and the song Tubb wrote with Sergeant Henry Stewart, “Soldier’s Last Letter,” written to Mom from the battlefield just before the Axis baddies did the soldier in. These were songs largely of glory and ore—a little mushy romantic interest aside—and were as inspirational to teenage Texans as those Hollywood war movies in which Erroll Flynn blew up half of Nazi Germany and then swam to attack a U-boat armed only with the knife between his teeth.

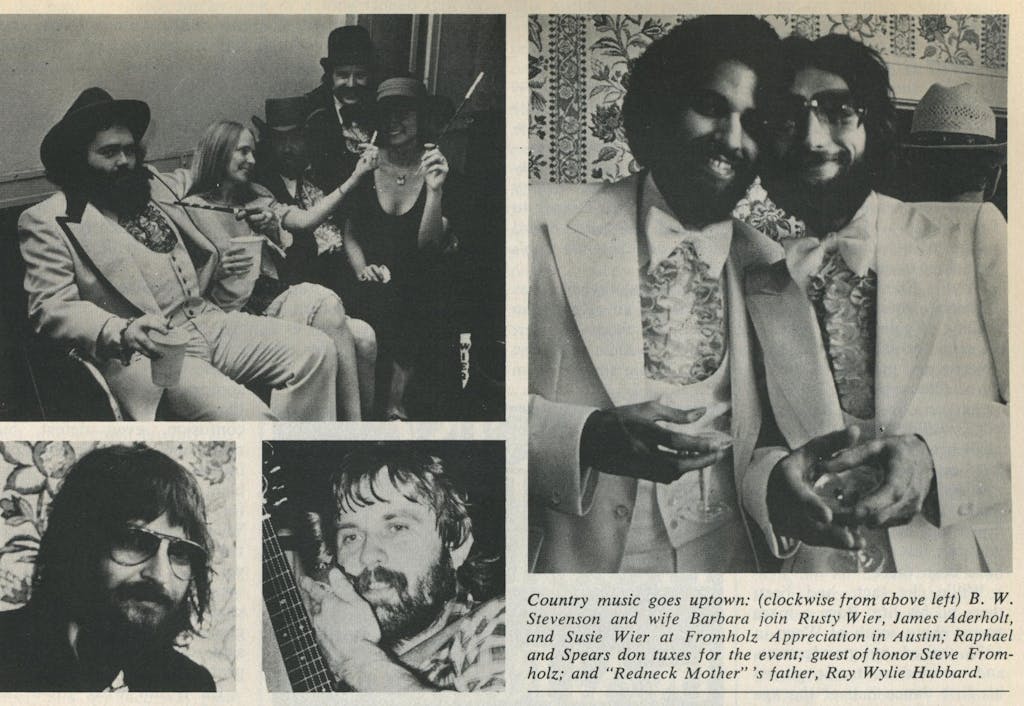

In recent years, especially among the musical “outlaws” and redneck rockers, songs of social protest have gained a new acceptance. (It is interesting to speculate whether the present conservative mood in the nation may send country music backlashing to the days when old-age pensioners and welfare loafers were considered fair game.) Tom T. Hall obliquely put down racial prejudice in “The Man Who Hated Freckles”; Merle Haggard’s “Irma Jackson” is a protest against ancient taboos frowning on interracial marriages, of all things; Billy Joe Shaver’s “Black Rose” laments the splendid misery of not being able to give up a minority-group lover. Steve Fromholz’s “Lanky Southern Lady” may be read by some as being about a midnight freight ride in Texas—and by others as about making it with a dusky lady. A 1967 song, “Skip-A-Rope”—enjoying a new popularity in these post-Watergate years—is of children at play chanting of things they’ve learned from the grownups:

Cheat on taxes. Don’t be a fool.

What was that they said about the Golden Rule?

Never mind the rules. Just play to win.

And hate your neighbor for the shade of his skin.

The hardest hitting of the social protesters, however, may be John Prine. He appears to have sat down with a list of the nation’s sins and social ills and then dashed off appropriate poetry with the notion of shaming us all. His “Illegal Smile” knocks the absurdity of harsh pot laws; “Your Flag Decal Won’t Get You into Heaven Anymore” is against yahooism and xenophobia; “Hello in There” is about the cruel fate of abandoned old people who look out on the uncaring world with “hollow ancient eyes”; “Muhlenberg County” should please environmentalists, with its tale of a father telling his son it’s too late to return to the old homestead “down by the green rivers where Paradise lay” because “Mr. Peabody’s coal train has hauled it away.”

Prine attacked the Vietam War by presenting a veteran by the name of “Sam Stone,” who returns from battle a junky:

Well, the morphine eased the pain

And the grass grew ‘round his brain

And gave him all the comfort that he lacked

With a purple heart and a monkey on his back.

There’s a hole in Daddy’s arm

Where all the money goes

Jesus Christ died for nothin’ I suppose.

Sweet songs never last too long

On broken radios.

These themes are from Prine’s first album and date back almost five years. His later work seems further off the social mark. Or is it just that, by now, almost everyone among the redneck rockers has preachified the social gospel? One would not be too surprised should super-square old Ernest Tubb come out with a dope song in which he confesses sniffing glue.

If John Prine has been the stolid social conscience among country moderns, then Kinky Friedman must win the crown for sheer irreverence—not, however, for irrelevance, although his flashy swaggering prompts some to dismiss him as a clown or a novelty act. Friedman easily offends because he’s about as subtle as a ballpeen hammer. His “Ballad of Charles Witman” never will win the Good Taste Award:

There was a rumor about a tumor nestled at the base of his brain.

He was sitting up there with his .36 magnum, laughing wildly as he bagged ‘em.

Who are we to say the boy’s insane?

His “We Deserve the Right to Refuse Service to You” takes on the redneck owner of a “bullethead cafe” as well as a rabbi concerned with the social niceties: “Your friends are all on welfare./ You call yourself a Jew?/ We reserve the right/ to refuse services to you.” “They ain’t Making Jews Like Jesus Anymore” might be the theme song of the Jewish Defense League in its declaration that “We don’t turn the other cheek the way we done before.”

When Friedman’s first album was released a few years ago, and I told my Eastern friends about him, they winced at the name of his group: Kinky Friedman and the Texas Jewboys. Yet, I am told, Jewish recording company executives wept on hearing the beautiful “Ride ‘Em Jewboy,” which in traditional country terms harks back to the pogroms and horrors of anti-Semitism:

Ride, ride ‘em Jewboy

Ride ‘em all around the old corral.

I’m, I’m with you boy

If I’ve got to ride six million miles.

Now the smoke from camp’s arisin’.

See the helpless creatures on their way.

Say, old pal, ain’t it surprisin’

How far you can go before you stay?

Don’t you let the mornin’ blind you

When on your sleeve you wore the yellow star.

Old memories still live behind you.

Can’t you see by your outfit who you are?

For all the songs about doping, drinking, poor exploited lettuce pickers, black lovers, or mass murderers, however, the country staple remains he-she songs. Though there are “happy” love songs, those of unrequited love long have prevailed. Perhaps this is because it’s somehow easier to write about losers than winners, of attritions rather than gains: there simply is more drama in it. Or perhaps the explanation is even simpler: more people lose than win, in love as in everything else, and these statistics lend themselves to easy identifications with songs of broken hearts. Besides, a good tearjerker goes better with beer drankin’.

In the long ago, country songsters were careful to leave the reasons for their heart’s disaffections decorously vague. One had to read between the lines to understand why Ernest Tubb was “Walking the Floor over You” or had “A Worried Mind” or felt he’d been “Born to Lose.” When I first heard those songs piped into Eastland County from KGKO-Fort Worth (where Tubb sang five mornings a week for $75), I figured ol’ Ernest to have had the bad luck to run into a show-off like Lloyd Sharp. We were in the fourth grade then and I expended recess and the lunch hour winking at Lena Ruth Green, who sometimes thrillingly reciprocated. Then one day, curse it, during the class volleyball game, somebody hit the ball so hard it lodged in the rafters of our creaky old school gym. Lloyd Sharp skinned off his tenny shoes and climbed to dangerous heights, the class holding its collective breath; by the time he’d rejoined mere earthlings every girl in the room—including Lena Ruth—had near-fatal crushes on him. I mooned around with the sweetass for the longest time, taking comfort in Ernie’s songs of heartbreak and figuring that maybe he, too, had run afoul of an erring volleyball. Whether or not the country poets of the forties and fifties spelled out the miserable specifics, we knew they’ve been did bad wrong.

The tone of many songs of love lost bordered on the accusatory: candy kisses mean more to you than any of mine; you’ve a cold, cold heart; I’m a fool to care when you treat me this way, or tell me those lies; if you loved me half as much as I love you, then you wouldn’t worry me the way you do. Some were vaguely threatening in predicting that day of pluperfect justice when thoughtless heartbreakers would get their proper comeuppance: you can pick me up on your way down; you’ll be sorry you made me cry; your cheatin’ heart will tell on you. The spirit of such songs of vengeance sustained me during that period when I prayed each night to my Texas Baptist God that the heartless Lena Ruth might sprout unsightly freckles on her flawless face and that Lloyd Sharp might be permitted to grow crops of warts on his nose and brow.

As late as 1948, though hinting at back-street affairs and mourning the dangers of honky-tonk angels, country songsters found it prudent to advertise doing the “right” thing in the end. You just didn’t leave Momma and the babies back then, no matter how high your carnal fevers, if you came from the country culture. Divorce still constituted a permanent family blot. Those who wrote the hit “One Has My Name, the Other Has My Heart” well understood conventional rural mores:

One has my name/ the other

has my heart.

With one I’ll remain

that’s how my heartaches start.

One has brown eyes/ the other’s

eyes are blue.

To one I am tied/ to the other

I am true.

One has my love/ the other only me.

But what good is love/ to a heart

that can’t be free?

So I’ll go on living

my life just the same.

While one has my heart

and the other has my name.

Even when one split the family blanket, recriminations were required. “Married by the Bible, Divorced by the Law,” a 1952 song, perhaps was a subtle suggestion that Ike deserved the presidency because he’d stuck it out with Mamie where Adlai and Ellen Stevenson had not been able to honor the conventional. Maybe it was OK with the judge—that song said—but celestial beings retained a stony disapproval.

In 1949 Floyd Tillman wrote what may have been the first really out-front diddling-outside-the-home song in “Slipping Around.” Even then, he paid tribute to the fear and retaliations of neighbors and kinfolk by hoping that some acceptable social solution might be found:

Though you’re all tied up with someone else

And I’m all tied up, too,

I know I’ve made mistakes, dear

But I’m so in love with you.

I hope some day I’ll find a way

To bring you back with me

Then I won’t have to slip around

To share your company.

Seventeen long years later, in 1966, the real-life realities were better faced. Mel Tillis’ “Ruby, Don’t Take Your Love to Town” was revolutionary in that it actually admitted the wife of a paralyzed war hero could, and did, harbor sexual considerations outside the capabilities of her disadvantaged husband. Significantly, it was written about “that crazy Asian war”; in a more popular war the wife would have been required to remain stubbornly loyal.

Among current hits is “That’s What Made Me Love You,” which minces few words about heat and hair and hands.

Tonight in a pouring rain

in a motel in Dallas

That’s what made me love you.

That’s what made me love you.

Champagne in a Dixie Cup

You had a little, I had too much.

That’s what made me love you . . .

In a hundred years I’ll think back

And I’ll have memories of

a box of candy and a wilted rose

Wrinkled sheets and wrinkled clothes.

That’s what made me love you.

That’s what made me love you.

The full impact of that song hit me recently as I scarfed the well-done house cheeseburger in Baird, Texas—only eleven miles from my place of birth—and an acned young waitress sang it out while serving up cornbread and blue plate specials and giant glasses of iced tea. Old nesters in railroad caps and cowboy khakis, their wives wearing pink rubber hair curlers and hoglike jowls, failed to faint dead away or scowl in protest. And I thought: Good God, Lawrence, country songs are allowing that folks are doing it for nothing more than mere fun and they don’t have to walk the aisle, birth babies, or experience Old Testament guilt in payment of the favor. Hail, boy, them’s my kinda people. . .

Yes, the music has changed. So have those who write it and sing it and play it. Most of all, perhaps, the folks who listen to it—the fans—have changed. It wasn’t all that long ago that country music was confined to Southern outback and deserved its designation as “hillbilly” music. Such rustics as remain in an urban America continue to pat their feet to it, but they no longer retain exclusive rights.

A decade ago, Texans and others of a certain educational level or upwardly mobile class were a bit ashamed of the music they’d cut their teeth on. They might turn their car radios down at stoplights so others in traffic wouldn’t hear them culturally slumming, no matter how many secret chords their native music touched in their souls. For if country music had escaped its hillbilly taint, if people no longer though of it as being fit only for the ears of mountaineers or farmers, it continued to be thought of as limited to working-class folk: those who manned the assembly lines, drove dump trucks, sweated in the oil patch. Radio piped the music to all parts of the country (and, on Armed Forces Radio, to many parts of the globe); recording companies discovered a booming market in country and western. World War II, bringing Northern soldiers down into the South and sending guitar-strumming Southern boys into Yankeeland, aided the cross-pollination. Still, the image remained of the music being for those who wore dirt under their fingernails.

Folksingers and bluegrass pickers began to receive enthusiastic welcomes on college campuses in the Fifties, and a new generation—getting into the Memphis blues sounds of Elvis, of Guy Mitchell’s rock-a-billy techniques, of the licks provided by Buddy Holly and Roy Orbison and Jerry Lee Lewis—opened their minds and hearts. Willie Nelson helped pave the way by bringing together the ropers and dopers, and, though purists have begun to gripe about all the so-called cosmic cowboys and fake rednecks resulting, there can be no doubt that the Austin “outlaw” movement taught the young and the educated to appreciate the old country licks while educating the natural rednecks to accept, in song, ideas they might have lynched you for if otherwise expressed. There are still fine performers and songwriters like Billy Joe Shaver, with his eighth-grade education, but there are also musicians who trained at North Texas State’s music department or even—as with Kris Kristofferson—brought along Rhodes Scholar credentials. The Top 40 charts continue to lean toward the basically traditional, even if the he-she songs are bolder than before, and when Willie Nelson cracks it, he’s more likely to do so with an oldie like “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain” than not. But the outlaws and the redneck rockers, dealing with new mores and formerly taboo subjects, have won powerful cults who fill up the halls to hear them perform-and who buy their records even if they receive fewer deejay spins than the old country traditionalists. There is a grand mixture now of styles and content, and while it may lead to disputes among modernists and traditionalists over matters of purity, there’s an overall higher degree of tolerance for the musical diversities.

A few weeks ago I stopped in the Grand Tavern in Mingus with one of my daughters and my eighteen-year-old son. It was a hot afternoon and sweltering, one of those days when the old nesters gratefully repaired to the shade and sipped beer and found it taxing to talk very much. The locals examined us—bearded and booted and long-haired—and offered information grudgingly until my son, Bradley, introduced his guitar, and before long the old nesters were tapping their feet and crowding around and buying beer while he sang of desperados waiting for a train, of having the London homesick blues, of a gal who ain’t going nowhere she’s just leaving, of a good-hearted woman in love with a good-timing man, of Mister Bojangles, of a brand of dope called Panama Red. It broke the ice and opened up the tale-tellers and brought about a community rather than remote, detached islands of men and women. We stayed two hours and left with warm invitations to return ringing in our ears. As we left I said to my son, “Well, do you think they’re ready for ‘Asshole from El Paso?’”

“Maybe not today,” he said. “But next week, next month . . .”

- More About:

- Texas History

- Music

- Longreads

- Country Music

- Willie Nelson