This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

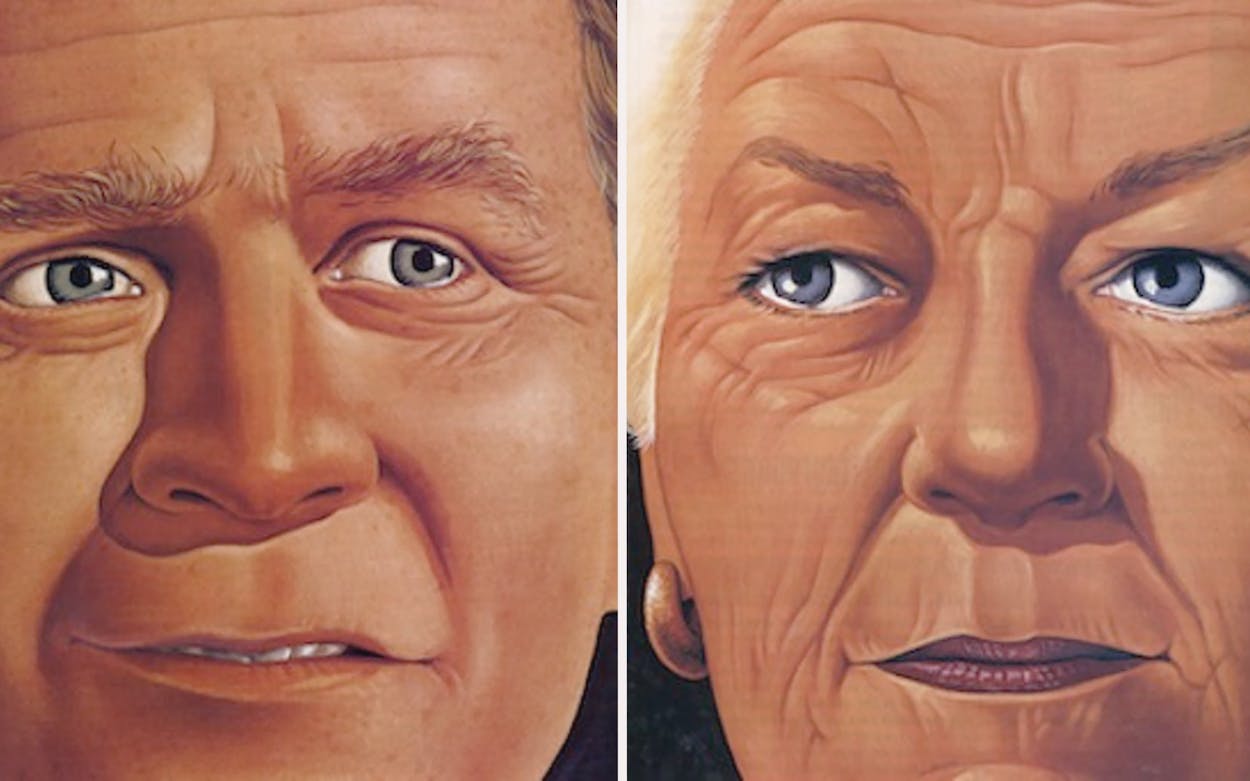

How do 18 million people go about selecting their leader? That is what Ann Richards and George W. Bush and their strategists have spent a year trying to figure out. Now in the weeks leading up to November 8 we will see which strategies pay off. Never has Texas seen such an interesting governor’s race in a general election, never has it had two candidates who are so well known nationally, and never have the political stakes been higher. If Bush and U. S. senator Kay Bailey Hutchison sweep their races, Texas will be a Republican state. But if Bush loses, who will be able to stop a leaderless GOP from spinning out of control to the right and forfeiting its chance to be the majority party? The future of several military bases, the South Texas economic boom, and major federal programs like the space station and the V-22 Osprey may depend upon a Richards victory. But if the state’s most popular Democrat since John Connally can’t win a high-profile race, what Democrat can? Here are the factors that will decide the outcome in November.

The Game Plan

Richards’ strength is her personality. Bush can’t beat her in a personality contest, so he has to beat her on issues and ideology. Her first TV commercial was a feel-good chat about a teen curfew. His was an attack on crime so crammed with statistics that it was reminiscent of Ross Perot’s presidential campaign ads. The spot had too many competing themes to be effective—crime, welfare, change, accountability, Texas values, all in sixty seconds—but it did succeed in setting the tone for a substantive campaign.

Richards will try to define the race as a choice between somebody who has done something for Texas and somebody who has done nothing and would be nobody if his last name weren’t Bush. “The questions to ask,” says a Richards strategist, “are, Who is he? and What has he done that would make you believe that he can keep his promises?” Her message will be that it takes more than position papers to be a leader; his will be that it takes more than quips.

ADVANTAGE: Richards Bush’s strategy is well designed, but for it to work, he must establish a credible political personality that goes beyond his name. After nearly a year as a candidate, he hasn’t done it yet—and the unfortunate killdeer incident, when Bush shot a bird that cannot legally be hunted, only reinforced his shoot-from-the-hip image.

The Political Climate

It’s perfect for a Republican challenger. Texas reflects the national mood that is pro-change and anti-incumbent. By positioning himself as the proponent of change and portraying Richards as the defender of the status quo, George W. Bush is trying to capitalize on the same voter emotions that cost his father the presidency. Now the voters’ surliness is directed at a Democratic president. Rural Texans in particular are mad at the Clinton administration over gun control, interference with landowners’ rights, and promotion of gay rights—all areas in which Richards herself is vulnerable. How much of that anger will be directed against Ann Richards? Bush’s polling strategists are predicting that the president’s unpopularity will cost the Democratic ticket a generic two to three percentage points—enough to be fatal to Richards’ reelection in a close race. But Richards is no generic candidate; her personal popularity affords her some protection against voter backlash. Just to be safe, though, she will seize every opportunity to distance herself from Clinton.

The biggest factor in Richards’ favor is the Texas economy. Half a million more Texans are employed today than when she took office. She made jobs a priority and can legitimately take credit for persuading General Motors to keep its Arlington plant open, wooing Hollywood producers to make films in Texas, and lobbying in Washington for NAFTA, the space station, and federal reimbursement for the supercollider. No governor has done a better job of being Texas’ ambassador to the United States.

ADVANTAGE: Bush Clinton is a heavy albatross, especially in East Texas, one of the main battlegrounds of the race. Economic development isn’t as big an issue as it was during the bust years, and its benefit to Richards occurs primarily in South Texas, an area where she is already strong.

The Battlegrounds

The Richards-Williams race of 1990 and Ross Perot’s bid for the presidency in 1992 accelerated the destabilization of Texas politics. Party ties are weak. Both Richards and Bush are crossover candidates who appeal to groups of voters normally loyal to the other party. Here’s where the candidates will be looking for swing votes:

Dallas This is the area that put Richards over the top against Clayton Williams in 1990. She ran as much as six percentage points ahead of normal Democratic results in the region. Although Bush lives here, Richards continues to run well in the polls. To regain this traditional GOP stronghold, Bush will exploit the unpopularity of the new school-finance law, which hurt Highland Park, Plano, and Richardson.

Houston If the Bush name still has magic in Texas, it’s in the family’s longtime hometown. That may explain why Richards is lagging in the polls in Harris County, which is usually friendlier to Democrats than Dallas County. Richards’ strategists attribute her disappointing early showing to the fact that Democratic working-class voters tend to get more interested in politics as election day approaches.

East Texas Bush is solidly ahead in an area that used to be Democratic turf. Cultural issues work against Richards in good ol’ boy country. She has to contest it, but she will almost certainly lose it.

Middle-class and affluent women This is the group that will ultimately decide the race. Many of them have been voting Republican—except in Richards’ 1990 race. Richards can afford to lose two thirds of the white male vote if she wins 55 percent of white women and picks up the usual Democratic support from minorities. If Bush can close the gender gap, he will win.

ADVANTAGE: Bush He ought to run better among women than Williams did—but will it be enough?

The Issues

Ann Richards can make the case that she has been a successful governor. She ran in 1990 on reforming insurance, cleaning up the environment, making government more honest, and starting a state lottery—and successfully backed new laws in all four areas. The state’s insurance and environmental agencies are less dominated by the industries they regulate and more responsive to the public than they have ever been. The ethics law eliminated the lavish entertainment—food, golf, trips, hunts—that legislators had come to expect from lobbyists. The lottery’s popularity has exceeded all expectations.

Unfortunately for Richards, her issues don’t count for much today. The biggest crisis of her term turned out to be school finance, in which her role was mainly to be a cheerleader while the Legislature struggled to satisfy court decisions that threatened to close the schools. The result—the widely loathed Robin Hood law—provided Bush with the opening he needed to make the race. Bush has been able to dictate the issues that will be critical in the campaign—education and crime—and Richards must fight the duel with the weapons he has chosen.

The problem for Bush is that there are no easy answers to the problem of what’s wrong with education. His solution for inequalities in the school-finance formula—increase state aid and reduce dependency on the property tax—would cost billions of dollars. How would he pay for it? His solution for poor schools is to liberate school districts from state control. But the most important reform of recent years—the 22-to-l maximum student-teacher ratio in early grades—is the state mandate that local districts hate the most, because they have to build new classrooms and hire new teachers. What happens if a home-rule district decides it wants to spend more money on athletics and less on smaller classes? Richards also wants some deregulation of schools; the main difference between Richards and Bush is that he would put school boards in charge, while she would give the management power to educators and parents at individual schools.

The crime issue ought to belong to Richards. She has authorized the building of more prisons than were built by all of the state’s previous governors combined. She appointed an ex-warden named Jack Kyle to clean up the corrupt parole board that she inherited from Bill Clements’ administration, and Kyle cut the number of paroles in half. New laws have doubled the time violent criminals must remain behind bars. But Richards threw away her advantage by trumpeting statistics showing that the crime rate is going down. The only statistic that matters is how safe people feel—and they’re scared as hell.

ADVANTAGE: Toss-up Richards ought to have the edge, but she doesn’t. For three years she has presented herself to the public as a personality, not as a substantive person. She and her oft-maligned staff failed to develop a message or a process of communicating with the public. Richards should be invulnerable on crime, and she could have reduced the damage done by school finance by touting (and shaping) the complete revision of state education laws that is currently taking place. Hardly anyone knows about it—and that’s Ann Richards’ fault. She has let George W. Bush seize the initiative on both issues.

The Real Difference

The most profound difference between Ann Richards and George W. Bush is not party or ideology or even gender. It is their opposing views of what the governor’s job ought to be. Bush puts primary emphasis on changing what state government does, by making new laws; Richards puts primary emphasis on changing who state government is, by appointing new people—giving traditional outsiders access to power. Bush believes in direct action; he is, after all, the man who told his father’s White House chief of staff, John Sununu, that he had to resign. Richards believes in evolutionary action brought about by widening the circle of decision makers—a New Texas, as she called it in her 1990 campaign.

These opposing job descriptions have produced an odd juxtaposition for Texas politics: The Republican candidate has positioned himself as more activist than the Democrat. Richards’ view of the office is closer to the limited role of the governor that is spelled out in the Texas constitution. In nearly four years as governor, she has shown little interest in the specifics of legislation. Bush’s proposals, on the other hand, are specific to the point of targeting the exact number of prison beds that he wants to convert from drug and alcohol treatment to incarcerating juveniles (1,500). In this race, Bush is the policy wonk, the kind of candidate his father defeated in 1988 (remember Michael Dukakis?) but lost to in 1992. Ann Richards is the candidate of a thousand points of light.

ADVANTAGE: Bush The New Texas was a failure; Richards’ appointees and policy advisers, with a few notable exceptions, were the weakest link in her administration. Bush is positioned better in every facet of the race except personality, and he has Barbara Bush waiting in the wings to campaign for her son. But the one area where Richards has the advantage is the one that counts the most.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- TM Classics

- George W. Bush

- Ann Richards

- Austin