Voodoo came up in a psychiatrist’s office. I was sitting on the couch asking questions for a magazine story when Betsy Comstock, who supervises emergency psychiatric care at Houston’s Ben Taub General Hospital, mentioned that patients were occasionally misdiagnosed as psychotic when they were actually laboring under a voodoo curse. “Voodoo in Houston?”

“Yes,” she said, “a lot of our black patients at Ben Taub have had contact with it, but it’s not nearly so prevalent, of course, as the Mexican American curanderos. They refer patients to Ben Taub on a regular basis.”

Two months later I was back in Houston looking for voodoo practitioners and curanderos. In the meantime I had learned that folk healers, traditionally shunned if not legally prosecuted in most areas, are now being considered by some physicians as folk psychiatrists more effective in treating culturally predisposed blacks and Chicanos than is the established medical system. I wasn’t so much interested in academic debate, however, as in trying to find out how curanderismo and voodoo work.

The first curandera I met I will call Eva. Eva wasn’t typical—she calls herself a psychic healer and most of her clients are Anglos—but she was nevertheless the real thing. I was instructed to arrive at her duplex in Montrose at 9 p.m. Sunday. I was not to eat or drink for four hours before arriving, was to bring Eva a rock and a flower, and wear something blue or purple.

Traditionally, curanderos are religious individuals who have a supernatural gift for healing. They are modest about the gift, never advertise, and accept money only by donation. They make no claims of personal power, as pride, it is thought, would turn the gift against them. Though purveyors of religion and white magic, curanderos must know black magic to confound the spells of brujos (witches) and are therefore considered potentially dangerous people capable of “working with both hands.”

Sunday night it was raining. I was hungry and nervous when I arrived and had the distinct sensation of moving into unknown territory. Eva’s husband, a slight man, let me into the apartment, which appeared ordinary except for a dining room table arranged like an altar with purple candles and a purple satin cloth. A large, strong-looking woman in a severe black robe came out and announced that she was Eva. She had dark brown hair that fell in precise waves down her back and was wearing a heavy silver cross at her throat, thick makeup, and wet lipstick.

Eva directed me to sit across from her at the table. Between us on the purple cloth were three candles and three crosses. A long curved dagger on a rabbit pelt and a small dieffenbachia plant were at Eva’s right hand, a small crystal ball to her left. Just as I was noticing her inch-long red fingernails, Eva began, “I am good at everything I do. Everything I do, I do well.” Seven hours later I staggered out into the Houston dawn feeling like an unwilling recipient of shock treatment.

The session had begun casually. Eva started by assuring me that I had psychic perception. Psychic power, she explained, comes from cosmic forces in space that the mind can transform and direct to influence either physical objects, as in psychokinesis, or the tissues of a person’s body, as in psychic healing. Uri Geller bends keys; Eva cures cancer.

Eva then told a series of stories with complete conviction, dramatics, and gothic imagery (cats howling in all the right places) that demonstrate her power to heal. Though at first Eva claims the power can be used only for good, she later told a story demonstrating her ability to eliminate through black magic anyone who harms her. The threat, accompanied by Eva narrowing her eyes and staring into mine as if reading my thoughts or giving me the evil eye, was implicit.

Having thus prepared and watched me for four hours, Eva asked for my rock. I placed on the table a plain brown stone my nephew had found on the beach. “The rock and the flower,” she chanted, “form psychic patterns of yourself. You and the rock have the same kind of life. Let me show you my rock,” she said, and pulled out a dazzling blue, green, and white composite of chrysolite, azurite, and quartz. So much for my psychic patterns. The rumpled white chrysanthemum I’d brought didn’t bear comment.

Eva then asked for a sample of my handwriting, looked at it, and made a few marks, and stepped across the boundary of goodwill and self-protection that people maintain between each other. “You are,” she began, and proceeded to tell me, with remarkable accuracy—no flaws omitted—who I was. It was somewhat like hearing a recording of your voice for the first time. At the moment, I was startled by her perception. Now, I see that Eva had entered the one zone into which I’m least able to see and told me what any observant person who trusted his or her intuition might know. She continued with the aid of psychological parlor games to tell me I was selfish, distant, would have back trouble, and that my y’s are like Hitler’s. By the time she had finished, she had usurped my right to say who I was.

It is at this point that the client is most vulnerable. What Eva doesn’t guess, the client usually confesses (I didn’t), and there is not only the immediate relief of being able to discuss secret problems openly, but also to discuss them with a person who offers magic solutions. The process is, I think, similar to Erhard Seminars Training: dominate, subjugate, humiliate, restore.

To demonstrate how she solves problems, Eva stood over the dieffenbachia on the table and poked it with a brass cross. The plant, she said, belonged to a client who had provided clippings of hair and fingernails and a photo of the person Eva was to work on. Eva put the clippings and photo into the plant’s soil and “in the name and the power of Jesus Christ” authorized the plant to take over the identity of the problem person. “These plants have to be strong,” Eva poked, “because I torture them, jab them with knives, and almost water them to death.

“To strengthen the client,” Eva went on, pulling a small aluminum-foil cross out of the plant’s leaves, “I use these little crosses. The crosses,” she peeled back the foil to show me, “are made by tying two twigs together with blue string and a strand of hair. When you cook with aluminum foil, you reflect off heat, when you crumble the foil around the cross, you have formed two powerful symbols. The foil reflects off the negative and evil.” Eva also has the client make crosses to spread around his or her house, yard, car, and person.

Plants and crosses not only solve emotional and social problems, but also cure terminal disease. Eva restricts herself to the incurable, because simple medical cases aren’t a challenge. “You don’t need me,” she said, “if a doctor can help you.”

She told the case of a man with lung cancer who she was able to heal. The client’s doctors were giving him cobalt treatment, but they had given up hope and told him he was going to die and he might as well smoke if he wanted. When Eva saw him, she said she could smell death. She attacked the cancer using a philodendron and crosses, made the man stop smoking, and told him to eat thirteen almonds and drink half a cup of grape juice a day.

“Within days,” she recalled, “he was out of the hospital, he gained weight, he began to look beautiful, color came back to his cheeks, his hair began to grow, and the philodendron began to look glorious.” The man died a year and a half later, because, Eva said, he became so healthy he decided he didn’t need her and he stopped taking almonds and grape juice.

I am not prepared to offer proof that Eva’s therapy was ineffective. The treatment with the plant is based on the voodoo-witchcraft belief in contagious magic. The premise is that things once connected can never be separated; what happens to a part happens to the whole. (In some ways her healing method is not unlike the visualization process Dr. Carl Simonton, a Fort Worth radiologist, uses in conjunction with cobalt and chemotherapy to treat cancer patients. Simonton has found that teaching cancer patients to visualize their white blood cells attacking cancer cells—troops of large white dogs attacking blacks rats or whatever—provides a relief of symptoms and a dramatic improvement in overall condition.)

Eva is deliberately vague about her clientele except to state emphatically that only one per cent is Mexican American and the rest are primarily upper-middle-class Anglos. For $13.50 an hour, Eva sits up all night listening to your problems and tells you they can be solved. She manipulates potent symbols (potent if you cook a lot with aluminum foil and read gothic pulps) to dramatize the situation and bring about an emotional catharsis and perhaps a new beginning.

Monday morning I tried to interpret the session with Eva as part of a healing tradition that includes Christianity, fifteenth-century Spanish medicine, European witchcraft, Mayan and Aztec beliefs, and modern medicine. Objectivity became difficult, however, when I woke with a pain in my back exactly where Eva had predicted. I had a distinct, uneasy feeling that I was unable to shake, and later in the day I fell down a flight of stairs, which only made my back worse. Though I rejected the idea that Eva was already working a plant on me to undo my skepticism, I did begin to wonder about my suggestibility. Moreover, I had the unpleasant sense of invasion that follows too casual intimacy.

Tuesday morning, still feeling edgy, I went looking for Stanley’s drugstore. Stanley’s is on Lyons Avenue in the black community just north of downtown Houston. To get across the bayou and the railroad yards that separate the two communities, is, if you don’t take the expressway, almost as difficult as stepping through the looking glass. Once there you see, framed by the burnt-out buildings on either side of Lyons Avenue and the prostitutes and drunks loitering on the sidewalks, the Houston skyline shimmering in the distance as real and approachable as a mirage. From that vantage point, it is possible to understand how voodoo beliefs of West Indian slaves mixed with Christianity and modern medicine have survived as a hardy American folk medicine.

Stanley’s drugstore is in one of the tougher-looking blocks on Lyons. From the outside, it looks like any other old-fashioned drugstore. It was a normal pharmacy until the neighborhood declined. When the demand for magic rose, the proprietors gave up their pharmacy license, and Stanley’s became a very special kind of drugstore.

When I walked in, several customers were occupying the attention of two white clerks. In the glass display cases that run along two sides of the room and across the end, I identified amulets, charms, crucifixes, crystal balls, Vapo-Rub, and voodoo dolls. A display of perfumes and powders with “alleged” magical power had names like “Do as You Please,” “Lets Get Together,” and “Essence of Bendover.” A large black woman in rundown house shoes and pale half stockings was lingering over the magical powders. “We lookin’ for something to move somebody,” she told one of the clerks. “Come all the way from Beaumont to help this friend.”

The other clerk was helping a woman pick out a candle from a large display shelf behind the counter. “Do you want the Jinx Removing candle or the Send Back candle?” the clerk asked as he picked up a large black candle. “If you want to send the evil back, you’d better use one of these. Burn it an hour each day and read Psalm Twenty-three.” The woman decided not to send the evil back and settled for Jinx Removing.

The telephone in the back storeroom rang a couple of times, some kids came in to get Cokes from the Coke machine, a tall black man with cataract-sealed eyes stopped in to beg from me, a middle-aged man rushed in to buy a Fast Luck candle, and a Mexican woman finally decided which amulet she wanted, but, when the clerk started to reach into the display case, asked that it come from the back room. Then the store cleared and I had a chance to talk to the clerks.

The clerks, Dr. Kim and Dr. Paul, explained that business was slow because of Christmas; everyone was spending money on presents.

“We aren’t really doctors,” Dr. Kim said. “Never have claimed to be, but that’s what all the customers call us, and we’ve gotten into the habit of referring to each other that way.”

“We aren’t Kim and Paul either,” Dr. Paul added. “We use aliases so customers won’t call us at home.”

The two clerks resembled one another so much in speech, gesture, and dress that physical differences aside, they seemed interchangeable. They are both educated, articulate men in their late twenties or early thirties, and they are both tall, thin, and wear faded blue jeans. To distinguish them, I latched onto Dr. Paul’s aviator glasses and Dr. Kim’s toupee.

“The level of crime here is extremely high,” Dr. Kim said, “but Stanley’s hasn’t ever been broken into and nothing’s ever happened to our cars. We’ve never been bothered on the street, but we mind our own business.”

Regarding magic, they said that in addition to black and white, there was red magic to draw love and green to draw money and tranquility. The magic worked too often, they thought, to discount its effectiveness. “A woman came in recently,” Dr. Paul said, “to buy a Black List candle—it has seven lines down the side for writing in the names of enemies. She stopped back the next day and reported, ‘Well, it worked.’ The first woman on the list had already had a car wreck. Another woman, a school teacher—a lot of teachers and nurses come in—got rid of her principal.”

“I’ll never forget the time one of our customers performed an exorcism here in the store,” Dr. Kim recalled. “Exorcised a little kid right there on the floor.”

Neither Dr. Kim nor Dr. Paul expressed concern that sick people spend their money on candles or incense rather than on medicine. Dr. Kim said he tells customers to go to the doctor but they won’t do it. “At least we can give them hope,” he said.

Hope isn’t cheap at Stanley’s. A voodoo doll that costs perhaps a dollar to make, sells for five. The markup is the cost of the magic. Just as clothes are more fashionable if they come from the right store, voodoo dolls are more powerful if they come from Stanley’s. (More powerful still in the Mexican woman’s mind, if they come from the back room.)

When I asked if anyone in the black community worked hexes, Dr. Paul said there were hundreds, but none would talk to a white reporter. They suggested I see one of Houston’s oldest and best black healers; he would know about black magic and I could probably get in if I went as a patient. They gave me the address. I will call him Dr. Perry.

Dr. Perry’s office is several miles north of Stanley’s where Houston begins to look like an East Texas country town. It is in a deserted-looking, two-story frame house. When I walked up on the screened porch and knocked, I thought I’d gotten the wrong address and was surprised that the door opened. A Mexican woman peered out at me and turned, leaving the door open.

Inside, the first room was arranged like a church. Rows of chairs faced an altar decorated with pots of plastic flowers, dime-store feathers, and plaster-of-paris saints. I took a seat on the second row behind a black woman and the Mexican woman sitting with her husband and child and, as I waited, contemplated one of several pictures of Christ in anguish. After several minutes of Christ’s anguish and my own, a woman stuck her head in from the next room, said, “Next,” and the Mexican family went in. The black woman turned and whispered, “This your first time?”

“Yes. Yours?” I whispered back.

“No, I come lots.”

“Not too many people,” I said.

“Just lucky. Usually this place is just full of patients waitin’ to see the doctor.”

“He’s pretty good?”

“Oh yes. He helps me with all my problems. Don’t be nervous when you go in. Just put your donation in the box he’s got on his desk.”

“How much should I put in?”

“Don’t matter. He won’t look.” She smiled and turned around.

The Mexican woman called the black woman in, a black man came to wait behind me, and then it was my turn.

Dr. Perry was sitting at a desk in an office down the hall. He was wearing a black satin fez, glasses, a woolly brown shirt, and gray suspenders with red cross-stitching. He looked, oddly enough, like a Russian peasant. Several of his front teeth are missing and much of what he said came out a gravelly “rrrrrrrr” that sounded like Louis Armstrong. I sat down in the chair in front of the desk, and he asked me my name and birthday and wrote both down on a pad of paper. Then he asked what my problem was. I’m not sure he’s deaf, but we were shouting at each other trying to communicate. Embarrassed and wondering what the black man waiting would think, I shouted that I had gone to a woman, a curandera, and I thought she might have put something on me. Half hoping for an exorcism, I told him about my back and that I had been feeling strange.

Dr. Perry looked at me for a second with friendly speculation and burst out, “Rrrrrr bull corn! Nothin’ wrong with you. Fine young man! Don’t listen to nobody! Nothin’ wrong!” He got up, led me to a small altar in his office, and made me kneel. Pushing my head down, he began to pray. For all I understood, it could have been in tongues or he could have been singing scat notes, but he was kneading my shoulders and that felt fine. After a few seconds of prayer, he put his hands flat against my back where the pain was, raised the fervor of the prayer, and with a climactic “Rrrahh!” threw his hands away from my back as if he were casting off evil. “Now. You’re better,” he declared.

At his desk, he wrote out a prescription on a pad, told me to have it filled, and come back. At the top of the pink slip of paper was printed, “From the Desk of Dr. Perry,” and at the bottom, “Take to Stanley Drug Co.” Dr. Perry had written, “Red candle—one hour each day—141 Psalm. Yellow candle—one hour—91 Psalm.”

I took the prescription back to Stanley’s where customers were standing two-deep at the counter and waited my turn. A tall black man who looked like Super Fly in a snappy hat and a tight leather jacket was standing next to me. When he caught Dr. Kim’s attention, he said, “Hey man, just wanted to tell you I’m already feelin’ better. You musta started.”

“Yeah,” Dr. Kim answered. “And I’ve got the list of people you wanted me to work on.”

“Great,” the black man said. Where his hands should have been, he had steel, hooklike prostheses.

Dr. Paul sold me a red candle and a yellow candle, and I headed back toward Dr. Perry’s. In his office, Dr. Perry carved crosses in the candles and anointed them with oil, prayed, said I’d be fine and to come back in a week’s time. When I left, I felt fine.

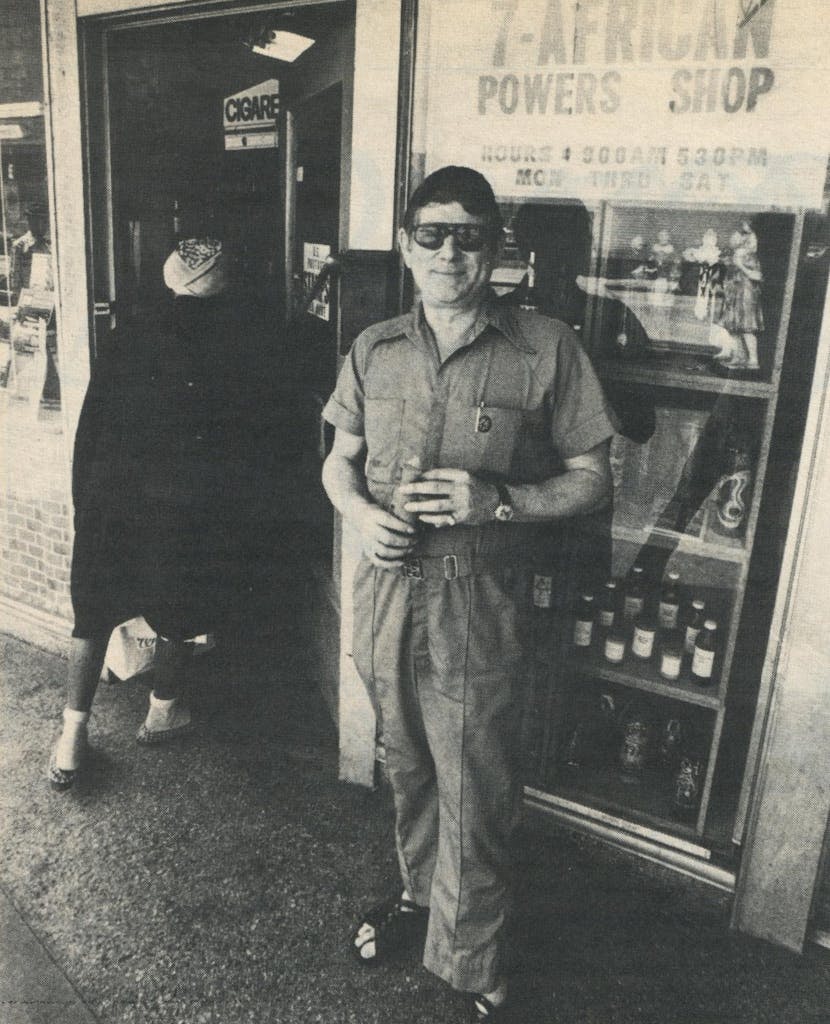

Back across the bayou and the railroad tracks, I stopped at the 7-African Powers Curio Shop in downtown Houston. It’s in the same block on Texas Avenue as the Greyhound terminal and Rosalie’s Intimo Theatre. Behind the counter a middle-aged man with platinum-blond, razor-cut hair said that their customers weren’t just blacks and Chicanos, but included “prominent wealthy people, lawyers, and other professionals.” They sold “tons” of voodoo dolls, which they “dress” (sew hair, fingernails, etc., of the person to be cursed onto the doll) for an extra $2.50. The man offered me a catalog and a card that advertised advice and consultations from Mr. Bill and Mrs. Cora, in addition to merchandise similar to Stanley’s. When I asked the man why people bought voodoo dolls, and whether they really believed in them, he gave his incisors a contemplative suck and said, “Bored. I’ve noticed everybody’s bored since World War II.”

Before leaving Houston, I tried to see a voodoo priest who works in the Cuban community, but he had gone to Miami for his Christmas vacation.

On the way to San Antonio, I stopped in Austin at the Mental Health Mental Retardation Center on East First Street to see Adele Freymann, the director. Freymann is a trained counselor, a Chicana, and is experienced with curanderos. When I told her what I was interested in, she took me into one of the group rooms where we could talk reclining on large pillows. The room—no furniture, wall-to-wall carpeting—is the perfect place to throw a fit.

Freymann said she could think of several curanderos in Austin and that there was a blind woman who was supposed to be psychic immediately next door to the MHMR Center. But most people in Austin liked to go to Bastrop, Lockhart, or someplace distant because that seemed like a mystical pilgrimage.

“Mexican Americans in general,” Freymann stated, “still prefer curanderos to mental health centers and priests, and it isn’t just the low-income, uneducated people who go. College students, professional people, Anglos, middle-class Chicanos who are interested in rediscovering their culture go to curanderos the same way they might try TM or mind control.”

Most people, Freymann said, think of a curandera as an old woman who rubs you with an egg. “The theory is that evil spirits or negative vibrations can collect in a person and make him sick. To cure the patient, the curandera has him lie beneath a sheet and rubs him with an egg while praying. The egg collects or sweeps up the evil spirits. The ritual is called a barrida or sweeping. After the barrida, the egg is broken into a dish and placed under the sick person’s bed. If an eye forms in the egg, it means the sick person is victim of mal ojo or evil eye. The evil is destroyed by burning the egg.

“Other things besides eggs are used—lemons, purple onions, flowers, and herbs will also do, but in serious cases of brujena (witchcraft), a black dove or a black chicken is used to collect the evil and then the bird is sacrificed. An egg can also serve as a live sacrifice, and it’s a lot cheaper.”

Freymann interrupted herself to ask if I’d been to El Porvenir, a store specializing in Mexican sweet breads and magical wares, and suggested we walk over. As we cut through a parking lot and housing project behind the MHMR Center on our way to Santa Rita Street, Freymann said that there were several different kinds of curanderos: parteras (midwives), sobadores (healers who use massage), yerberos (herbalists), as well as curanderos who read cards. Freymann thought they were all pretty effective counselors because they deal with the entire family, make house calls, and are always available to provide “instant reduction of stress.” The card readers, she said, could tell a lot about you by your looks and body language, and generally gave fairly good advice.

The sign above El Porvenir advertises Pan Mexicana, Herbolario, Abarrotes (Mexican bread, herbalist, groceries). Inside, beyond the livid pink and green cookies, there’s a stock of herbs, candles, and amulets. Freymann and the girl behind the counter struck up a conversation about cures. The girl said she knew a woman who had suffered from susto (lingering anxiety and debility caused by magical fright). To cure her, the curandero spread a handkerchief over her face while she was sleeping, poured whiskey on the handkerchief, and blew. It gave the woman quite a shock, but it cured her, the girl said.

Walking back to the center, Freymann said she went to a curandera thirteen years ago as a client. She was living in Corpus Christi, had just separated from her husband and felt her life was falling apart. A relative stopped by and suggested they drive to Nuevo Laredo to see a woman who could help her. They got in the car and took off.

The curandera in Nuevo Laredo said she could see that Freymann wasn’t ready to end the marriage and, if given the proper tools, promised to bring the husband back. She instructed her to return in a week with a photograph of her husband and she would prepare a magic powder. When Freymann returned, the curandera gave her prayers to say three times a day for thirteen days and a jar of powder to bury beneath her steps. Meanwhile, the curandera would be working on the husband with her psychic powers, and on the thirteenth day he would return a changed man.

“It worked,” Freymann concluded. “Thirteen days later he walked in the door and he acted completely different. It may have just been a coincidence, but seeing the curandera did get me past the crisis and it changed my behavior, too. We finally got a divorce, but not until a couple of years later when we were both ready.”

The blind curandera next door was not at home.

Robert B. Green Hospital on the west side of San Antonio is a lesson in how narrow the American mainstream can run. Culturally it is so much another world, it suggests the possibility of another world spiritually. From the time I entered the psychiatric clinic, I heard only Spanish and saw only one other Anglo.

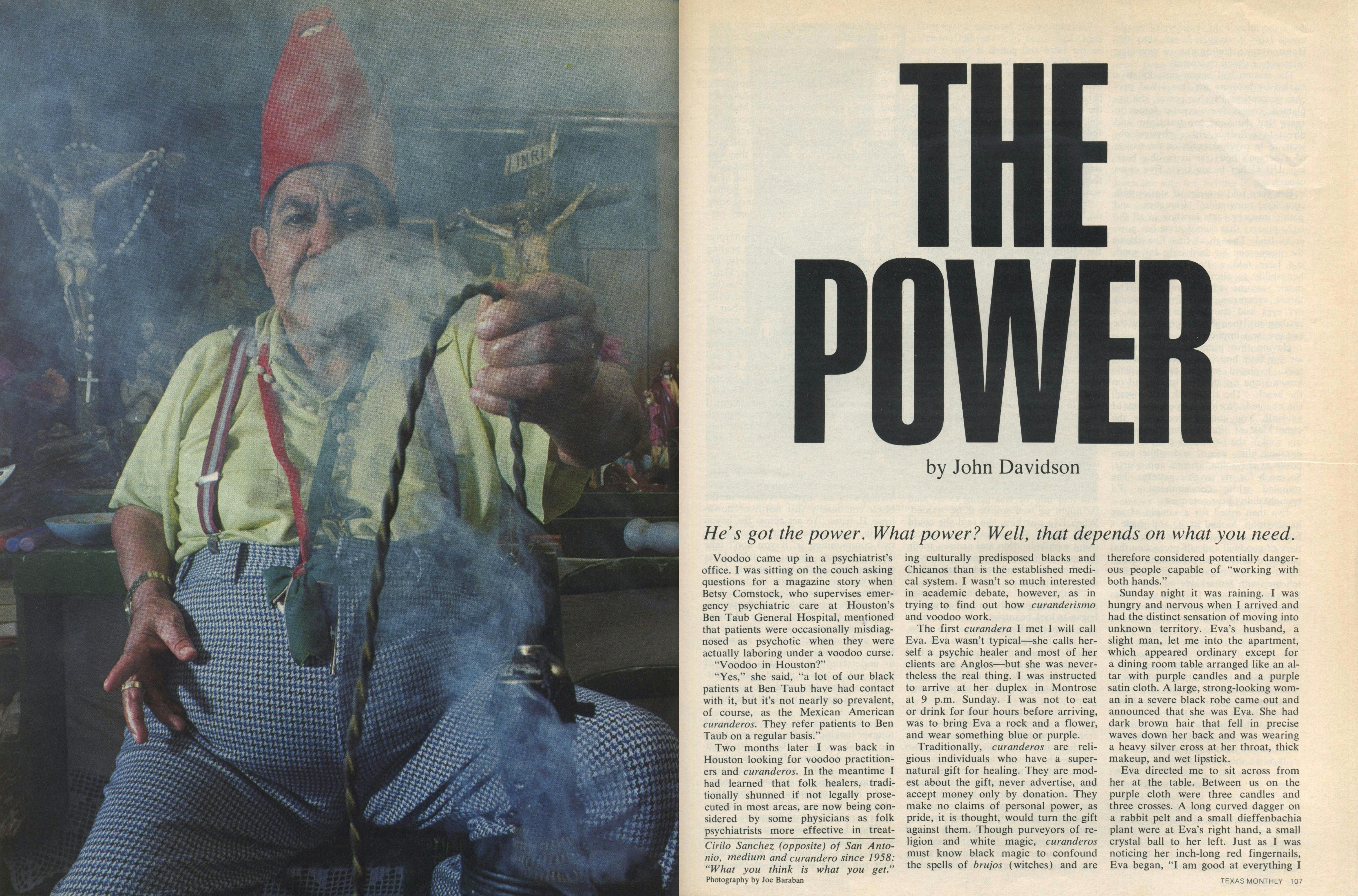

Cervando Martinez keeps up with curanderos through his patients at Robert B. Green and as an assistant professor of psychiatry at UT’s Health and Science Center in San Antonio. He gave me a list of seven local curanderos with addresses and said he could talk to me later in the day. Two names on the list were checked: Cirilo Sanchez was atypical and would talk to anyone; a Mr. Castro, whose name I have changed, was probably the best in the city and wouldn’t talk to a journalist.

The atypical curandero was easy to find. A large sign in front of his house announced in Spanish: Invisible Hospital of St. John the Baptist—Spiritual Center of Prayer, Curing, and Culture. I went through the side entrance into a long, empty waiting room, rang the buzzer, and sat down across from two homemade mannequins engaged in struggle. (The white figure in a platinum blond wig was getting the better of the red mannequin.) Brother Cirilo Sanchez, according to an advertising flier, offered treatments for—among other things—nervousness, high blood pressure, epileptic fits, cancer, arthritis, ulcers, alcoholism, “sexual weakness on men,” tuberculosis, menopause, and also problems of love, marriage, and salaries.

A señora answered the buzzer and let me into a long, narrow “examining room.” A twenty-foot-long altar peopled by a multitude of plaster saints ran along one side of the room and a row of old theater seats painted kelly green lined the other side. At the center of the altar by the kneeling rail, I noticed amid the religious paraphernalia two leather whips, a large curved sword, a red crown of leaping flames studded with eyeballs, and a pink Princess telephone.

An interior door to the examining room opened, and a small man in black lace-up boots, sky-blue double-knit pants, suspenders, and a short-sleeved, stay-press shirt entered on an aluminum crutch and leg brace. He began the interview by saying, “I am nothing. Only an instrument of God’s will.”

Sanchez became a curandero in 1958, he said, when John the Baptist ordained him through a medium. He has been studying for fifty years, has read all of Allan Kardec, the nineteenth-century French psychic, uses herbs, and in the last six or seven years has been gathering the power to perform exorcisms. He is also a medium himself and has been visited by the spirit of Pope John XXIII, and another pope whose name he couldn’t remember. “I got a lot of popes coming through my body,” he explained.

The long altar is a vision of the River Jordan that came to Sanchez through a dream. He pointed out a thin trough of water that flowed through all the plaster saints that depicted the birth of Christ, the baptism, the Last Supper, and the crucifixion.

Before delving into the esoterica, I asked about standard folk illnesses. Mal ojo is caused by a person who is very magnetic, he said. If the magnetic person looks admiringly at another person, plant, animal, or object and doesn’t touch it, then it will be harmed. “If I say, ‘Oh, what a cute beard you have!’ and I don’t touch it,” he explained, touching my beard, “then I might harm you.” Wearing a rosary of garlic cloves, snake bones, or buckeye seeds wards off evil eye.

Taking up a whip, Sanchez said that obsession was the main problem most people had, but it could be remedied by whipping the spirit. “Obsession caused by mal puesto [hexing]?” I asked.

“Yes, or just bad thoughts. Whatever you think is what you get. Particularly bad. I just try to get people to think positive; anyone who knows what he wants and loves it can do what he wants.”

I asked if I could watch an exorcism, and he said it would be all right with him, but since his stroke a year ago, not many people came. It distressed him that the stroke should be interpreted as a sign of vulnerability. “The people don’t see how it was God’s test for me,” he said. “I proved myself by living.”

After leaving Mr. Sanchez, I picked a woman’s name at random from Dr. Martinez’ list. Her street came to a dead end at a large thoroughfare, but after three detours I found a miserable turquoise shack. Three teenage girls watching soap operas in the front room said I could see their grandmother, and one of them showed me into the next room, where a toothless old woman was sitting on the edge of a bed. When I asked how she was, the woman said her kidneys were bad and the medicine didn’t help. She showed me a prescription bottle. I apologized, explaining I had thought she was a curandera. “Sí, sí” she brightened, “Hace años curaba y lavaba, pero ya no” (Yes, years ago I cured and washed, but no longer). “Lavaba?” I repeated, wondering if it was a curing technique that involved washing.

“Clothes,” the granddaughter said. “She did laundry, but she’s too sick now.”

At the medical school later that afternoon, Dr. Martinez said most of the healers in San Antonio were old and the future of curanderismo was uncertain. He hesitated to classify curanderos as folk psychiatrists, saying that though they might offer crisis intervention, the true goal of psychotherapy was longterm personality change and behavior modification. “Occasionally,” he went on, “when the family of a psychotic patient is struggling for an explanation for the sickness and is ambivalent about the hospital, we refer to a curandero. If the patient is hysterical and suggestible, then treatment by a curandero can be helpful.”

Tuesday morning I went looking for Mr. Castro, the curandero reputed to be good but shy of outsiders. I found him in his backyard standing over an orange flame which leapt out of green winter grass. Head down, lost in the flame, he didn’t hear me. As I walked closer and called out again, I saw at the base of the flame a pie plate and a circle of green grass singed by the burning alcohol. I called again.

“What?” His annoyance was plain. “What?”

I apologized and stated my business. He looked at me carefully—his pale eyes appeared to penetrate—and told me to go around to the front. I waited at the front door until he led me into a dark chilled room. An altar was decorated with plastic flowers, several pain-filled Christs, a plastic skull, and an American flag. We sat in our coats beneath Christmas streamers hanging from the ceiling.

Mr. Castro was happily employed as a school janitor when God gave him the gift of healing. “To tell you the truth,” he said, “I didn’t want to take it. I loved the kids and it was the same with them. But then I come to see some lights. I didn’t want to see anything, but I started seein’ little lights on the floors I cleaned. Little diamonds or sparkles. They was on the little boys’ faces too and the color of their faces would change. I was confused. Got so sick I had to leave school. Had to have shots for bronchitis. Then they took me to a healer. I wasn’t religious, didn’t believe in healers, but he said I was one too, so I started going to concentration meetings to be a healer. That was in 1958.” Mr. Castro, at 59, appears healthy and young. He is short and has a fair complexion and silver hair that looks blond. Between 1 p.m. and 1 a.m. six days a week, he sees fifteen or sixteen clients. The first visit, he takes only their names and birthdays and talks with them. Most of them come because they have too much on their minds, he said. “They’re having bad dreams and feel sad and heavy.” Some come with pain, but if Mr. Castro can’t “get his hands on it,” he sends them to a doctor.

To treat patients, Mr. Castro performs a barrida with an egg or prescribes taking three parsley baths three days in a row to take away superstitions and drinking three soda waters each day. “Drink half and throw half away.”

“Soda water? What kind?”

“Big Red. I give people orders, but the orders come from God. God tells me.”

“Tells you?”

“Yes, I hear God.”

“What does he sound like?”

“He sounds like he’s from the dead. He has a light voice.”

“You hear the dead, too?”

“At the concentration meetings. People go into trances, a cold wind comes to the body and speaks in the voice of the dead.”

“These are the same concentration meetings where you went to become a curandero?”

He said they were the same but that now he led the meetings twice a month; there would be a meeting Sunday night. When I asked to attend, he said, “No, I don’t think so,” but his intonation meant yes. I got the address and said I would be there.

“What was the flame?” I asked on the way out.

“For a client. I was working on a client.”

After spending time on the other side of the tracks or expressways with curanderos and their colleagues in Houston, Austin, and San Antonio I started to notice that my view of things was changing perceptibly. Everything was falling into recurring patterns of opposites: curandero/brujo, faith healer/witch doctor, black/white, Spanish/English, sickness/health. The oppositions, simplistic and at times inaccurate, are reinforced by the social division and by the fundamental division of magic into opposing realms of black and white. This dualism pervades magical thought so that the world becomes a place where everything has an opposite, everything is connected, and everything is controlled by forces of good and evil.

The magical view sees two kinds of sickness: natural and unnatural. Natural illnesses are those brought on by forces of the environment, bacteria, and by God as punishment for sins. Unnatural illnesses are the result of witchcraft. Medical doctors are thought to be incapable of treating illnesses caused by God or witchcraft. Nevertheless, “for every illness there is a cure” (more opposites). There are people capable of manipulating good and evil forces through the use of candles, perfumes, oils, and hexes to heal or cause harm. Unlike modern medicine, no illness is ever declared incurable, and the practical result is that many blacks and Mexican Americans don’t go to medical doctors; won’t accept the chronic nature of diseases such as diabetes, arthritis, and high blood pressure; won’t take prescribed drugs; and automatically attribute mental illness and undiagnosed sicknesses to witchcraft.

Magic and its practitioners, in the light of all this, are easy to judge harshly until you consider that for many people there is no alternative. In times of crisis, the key element for survival is often hope, and that is exactly what magic provides. If, as it has been estimated, 80 per cent of the visits made to general practitioners arc for emotional as well as physical problems, then curanderos are probably successful in at least 80 per cent of the cases. Hexing, if it doesn’t necessarily improve the health of the recipient, does provide a release for aggression safer than gunfire. In Haiti, hexing moderates violence so effectively that homicide was practically unknown until Papa Doc Duvalier assumed control in 1957.

Sunday evening I found the address for the concentration meeting on a side street behind a large cemetery in West San Antonio. About ten middle-aged Mexican Americans were waiting in the living room, and though Mr. Castro wasn’t there, the owner of the house greeted me in English and said I was expected. Everyone continued talking in Spanish about a young man they knew who had just been killed in a bar and how to stop smoking. A teenage boy and his two younger sisters arrived—all in Adidas track shoes—and then an old woman with a great mane of dyed red hair and a child’s body came in. She was wearing an eye-jarring pink, blue, and yellow shawl over a white religious habit. She had a smoker’s voice, seemed to know everyone, and laughed a lot. Her parts were so incongruent that I found myself adding up neck, shoulders, chest, waist, to see if they were all there. Another woman arrived alone and then a country-looking man and his rather wan wife. The owner of the house said it was time and rose to lead the way.

We filed through the house, out the back door, and across a wooden walkway above the backyard that led to what looked like a large toolshed. Mr. Castro, a priest’s purple sash across his shoulders, stood at the door until the women who stopped to put on white robes came and then he closed us in.

The impact of the incense-filled dark room was immediate. Above, a large round light pulsed purples and reds like the magnified eye of a fly and there was the echoing sound of a recorded Latin mass. The room was as thick with religious and magical icons as with incense, and it took a moment to sort out the images of Christ, Buddha, and the Virgin Mary among the various saints, spiritualists, and folk saints. Christmas streamers hung from the ceiling and there were three sky-blue pulpits for the sun, the moon, and the stars. Mr. Castro and two other men took the pulpits, the five women in white sat together, and we all formed a circle sitting around the room.

Mr. Castro delivered a long invocation to God and the spirits above the sound of recorded religious music and then moved around the circle marking each of us on the throat, the wrists, and forehead with small crosses of scented oil. Each of us, he said, should remove anything metallic such as wristwatches and we should be sure not to cross our arms or legs as it would interfere with the spirits. Music was handed out, we sang, we prayed, a fretful woman who had come alone made a long speech about how wonderful the meeting was and what a bad person she had been, Mr. Castro flipped the LPs on the record player, and the woman with red hair started trembling.

The trembling rose and fell, mounting to inconclusive intensities preceding a slow sad ebbing away. Sitting with head back and eyes closed, her powdered face clinched, the woman was straining to project her spirit into the world of the dead. I tried to imagine the desire and to picture such a world, it helped to think of someone I had lost to understand the abandonment.

A stolid-looking woman in white slumped in her seat next to the woman with red hair. She nodded a moment to the droning prayers, then jerked up. Short panting gasps escaped her as she rose automatically to her feet. The gasping accelerated, her arms began to swing, and she rocked back and forth in her sensible black oxfords as if attempting a leap into cold space. Chilled incomprehensible words trembled from her mouth, and it appeared from the swinging arms that she was launched in flight.

Everyone rose and the circle revolved before her, each person stopping to be touched blindly with her hands. I didn’t understand anything she said, but Castro said the spirit was San Martin de Porres, the black Peruvian saint who cares for the poor. He was healing us through her hands.

After more prayers and songs, there was a break with coffee and pan dulce. Everyone visited, the three teenagers gave Castro a Christmas present, and the date of the next meeting was discussed. All the people I was able to talk to were from small South Texas towns or from Mexico. No one appeared to have a particular illness.

The ceremony began again and the woman with red hair started trembling. Watching her, the curandero, and the others, I thought of the various explanations of spiritualist meetings I’d read: role playing, group therapy, acting out aggressive desires, a socially accepted way of going crazy. A refrain from one of the songs on the record player caught my attention: rompiendo la monotonía del tiempo: breaking the monotony of time.

With a jerk, the trembling woman was seized. She rose to her feet, but rather than appearing airborne, she was calm and serene. Each of us passed before her to be blessed and healed.

The meeting ended at 11 p.m. Driving back to Austin, there were long stretches of gray fog to match the mood I’d fallen into. For all my skepticism, I was actually disappointed not to find a hidden and mysterious world, but I was incapable of the leap of faith required for mystical experience. Magic succeeds without explanations: the less known, the more potent. I had demanded reasons and so got information rather than belief. After the initial impression, the meeting hadn’t seemed especially bizarre or the participants that peculiar: just people with limited resources looking for something to believe in and belong to in the city. Thinking of the story I had to write, I remembered it was the dog who pulled the curtain on the Wizard of Oz.

- More About:

- Health

- Longreads

- San Antonio

- Houston

- Austin