This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Most weekday mornings, a middle-aged man in a dark suit parks his car in a Fort Worth neighborhood, picks up some cemetery brochures from the seat, and begins walking door to door. Usually when he rings the doorbell, there is no answer. Most people who do open the door close it quickly when he tells them that he is a “memorial estate counselor.” Under the summer sun, he looks almost pathetic, this near-sighted salesman in his lace-up shoes. His small brown eyes are set deep into his sockets. As he walks from home to home, his shoulders sag.

And then, on occasion, a housewife holds the door open for an extra second. She looks again at this salesman offering her lawn and mausoleum space in the Greenwood and Mount Olivet cemeteries. Her eyes narrow in recognition. “Aren’t you …” she begins and then pauses.

“Yes,” the man replies in a voice as deep and resonant as a gong. “The voice,” other ministers used to say with a chuckle. “The voice that sounds like God Himself.” He hands her a brochure and asks if she would like to talk about her plans for the future, when her time of death draws near.

It was only four years ago that Joel Gregory, then 42 years old, was named pastor of the First Baptist Church of Dallas, the most influential non-Catholic church in America. For nearly one hundred years, First Baptist had known only two pastors—George Truett, who ran the church from 1897 to 1944, and W. A. Criswell, who is probably the most famous church minister in American history. A white-haired, granite-jawed Protestant pope, the 84-year-old Criswell used his explosive style in the pulpit and his sharp administrative skills in the office to build First Baptist into America’s biggest Protestant church, with a reported 30,000 members, half of whom don’t even live in the Dallas area. The church itself, spread over five square blocks of downtown Dallas, is worth hundreds of millions of dollars. (The church empire includes a thousand-student academy, a four-hundred-student college, a three-hundred-bed homeless shelter, and a radio station.) It is not only a center of Dallas power—the church for oil company presidents, corporate lawyers, real estate barons, and a collection of very rich dowagers (including Ruth Hunt, the widow of H.L. Hunt)—but it has also had an impact on many religious and social issues that have arisen in the last half-century. Granted, there are now other Baptist churches with larger Sunday attendance: Second Baptist in Houston, the sleek, modern megachurch with a convention center–like auditorium, packs in 11,500 at its Sunday services, while Dallas’ First Baptist, with its stately one-hundred-year-old sanctuary of varnished pews and stained-glass windows, draws in some 4,500. But First Baptist remains the bellwether of the 16-million-member Southern Baptist denomination. Billy Graham has been a member here since the fifties, although he lives in North Carolina. When people want to know what Baptists are thinking, they turn to First Baptist in the same way that Catholics turn to the Vatican.

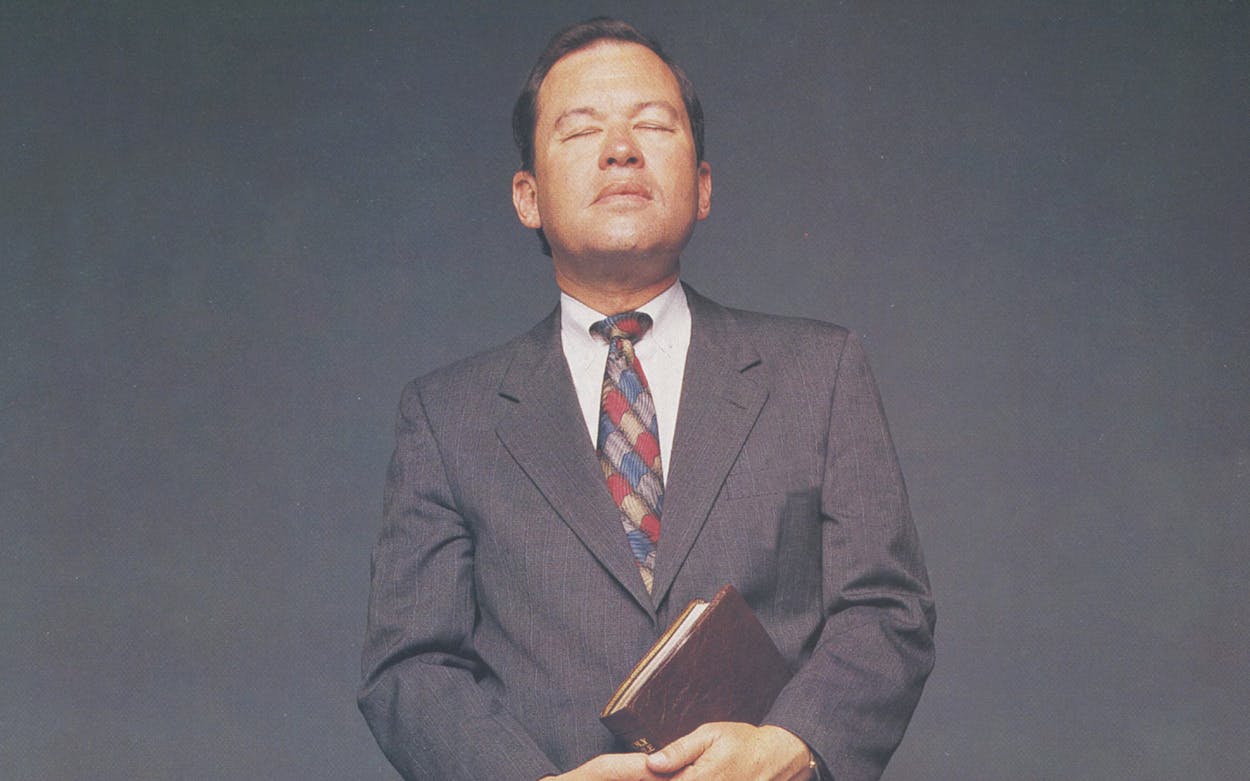

In the late eighties, when Criswell let it be known that he was preparing to step down, a church search committee spent 27 months looking at the seventy best young Baptist pastors in the country, most of them quarterback-handsome men with great smiles and charming manners. But when it was over, they picked the ugly duckling, Joel Gregory, a common-looking man of astonishingly uncommon erudition. Though shy and bookish offstage, Gregory had become known as the greatest pulpiteer of his generation. Far from the old grits-and-gravy, hell-raising revivalist of Baptist tradition, Gregory was an intellectual who, in his canyon-deep voice, could turn complicated theology into poetry. Even the proud Criswell himself says, “To this day, I still believe he’s the best preacher you’ll ever hear.”

But on September 30, 1992, after only 22 months on the job, Joel Gregory stood up at a Wednesday night service, read a perplexing letter of resignation, and—accompanied by two private detectives—hustled off the platform and out a side door. Once outside, he started running, leapt into a private detective’s car, rode for a few blocks until he was certain he was not being followed, then quickly got into his own car, which had been parked on an obscure downtown street. He was never seen at First Baptist again. Within seven months of his getaway he had separated from his wife, stopped speaking to most of his friends, moved to a small apartment in Fort Worth, and begun selling cemetery plots and prearranged funeral services.

Why did a man at the pinnacle of the Baptist church sneak away from everything he had known? For the past two years, the question has proved to be of almost obsessive interest to churchgoers and non-churchgoers alike. This month, with the release of his book Too Great a Temptation: The Seductive Power of America’s Super Church, Gregory breaks his silence and explains his resignation solely as the result of a power struggle with an imperious Criswell, who, says Gregory, was unwilling to hand over the reins of the church to a younger man. He describes Criswell, who is celebrating his fiftieth anniversary at the church, as “the artful Dodger” and “the Great White Father.” He adds that Criswell’s wife, Betty, the formidable grande dame of the church, also marshaled her own followers in a campaign to ruin Gregory. “Criswell and his wife Betty had been undermining me since I set foot [at First Baptist],” Gregory writes.

Even before its publication, the book created an uproar in Baptist circles. Gregory has become the most hated figure at First Baptist since, well, the antichrist. When he agreed to pose for a photograph for this magazine on a public sidewalk outside First Baptist, church security guards raced up, tried to interfere with the photographer, told Gregory they were “ashamed” of him, and even turned off the lighted First Baptist sign outside the church so it wouldn’t appear in the photographs. Although most First Baptist staff members and deacons publicly refuse to comment on the book, privately they are in a rage. They insist that Gregory is a backstabbing upstart who has invented a feud with Criswell to hide the real reason that he quit. They claim that he was having an affair with another woman. Some First Baptist leaders suggest he ran out of the church with bodyguards because he was afraid of that woman’s husband. One church official even provides a list of names of people in Fort Worth who supposedly know about Gregory’s secret life.

“The rumors go on and on,” Gregory says one evening in his Fort Worth home, the location of which he asks not to be divulged because he fears reprisals from his enemies. “I’ve been told that I have a girlfriend in Florida who has given birth to my illegitimate child. I’m supposed to have a girlfriend at an East Texas truck stop. I’m supposed to have been seen wearing a leather jacket at Billy Bob’s country and western nightclub.” His face turns gray. “It is all a groundless lie.”

Gregory says that a rumor of womanizing is what First Baptist always uses to destroy a man it doesn’t like. “What else were they going to say? That I prayed five minutes too little each day? My reputation has been deliberately destroyed, and all from the cloak of anonymity.” Indeed, when asked to provide any evidence of Gregory’s alleged adultery, the very people who claim they know about an affair quickly back off. Still, the rumors have so thoroughly saturated the Baptist community that it’s hard to find anyone—even the most thoughtful professors at Fort Worth’s Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary, where Gregory was a brilliant student—who does not believe some sort of scandal took place.

As it turns out, another woman did, much later, show up in Joel Gregory’s life. But Gregory’s downfall is far from the standard tale of a backsliding preacher. There is another story here—one hardly addressed in his own book—about a serious, somewhat withdrawn young man who spent his career struggling with a side of himself that he once described in a sermon as “the black bitterness.” Although his preaching propelled him into prominence—straight into the hallowed inner sanctum of First Baptist—Gregory still seemed to be tormented. In part, he was tormented by the regal and unyielding Criswell, the man who was once his hero. But at times, Gregory also seemed tormented by doubt, perhaps even depression, as if he felt unable to live up to his own spectacular voice, which everyone had told him was such a blessing from God. “I’ve even heard that he gives evidence of having turned aside from his faith in the Lord,” says Criswell, sitting one afternoon in his office laden with French antiques and English paintings. The great pastor wearily shakes his head. “It’s just been beyond my thinking,” he says.

Belief had never wavered since his earliest childhood. It was as firmly fixed in his character as the language he spoke. Nurtured on the Bible, Joel Gregory was staunchly chaste, an avid Baptist churchgoer. “I don’t think he ever once got in trouble,” says his younger sister, Margaret Forbes. The bookworm of Fort Worth’s Arlington Heights High School, the bespectacled Gregory was so precocious at science that he was one of four students in the county to be chosen for a national biology research project. “I was shier than average,” he says, “but I did have a kind of promotional streak. ” On Tuesday nights he would accompany his father, Cliff, a prosperous Nutrilite vitamin distributor who had built an organization of salesmen throughout Fort Worth, to the weekly sales meetings. There, the elder Gregory—a tall, handsome man, and an elegant dresser—would deliver a stirring motivational talk to fire up the troops. Joel would go home, turn on a tape recorder, and reenact his father’s speech, playing the tape back and re-recording until he got the delivery just right.

It wasn’t until he reached the age of sixteen that he realized the time had come to publicly show that he too could do what his father did so well. He was, as he tells it, sitting in Fort Worth’s Connell Baptist Church during a Vacation Bible School service. “It was like God ripped the roof off the church and said, ‘I want you!”’ Gregory says. “I literally felt seized and pushed forward to go preach—and I never thought about anything else from that very moment.” Gregory went down to the front and told the youth minister that he had just been called to become a pastor himself.

Baptists are not unaccustomed to such declarations—especially the 2.6 million Baptists in Texas. As Newsweek once wrote, Texas is “where Southern Baptists have literally inherited the earth and faith is as partisan as football.” According to one study of Baptists, more Texans read the Baptist Standard every week than any other weekly publication. Preacher Boys—the Baptist nickname for young men who feel the call to enter the ministry—abound in local churches. About the same time that Joel Gregory was becoming a Preacher Boy on the west side of Fort Worth, O. S. “Butch” Hawkins—a fun-loving, good-looking middle-class teenager whose dad worked as a city food and drug inspector—was hearing the call at Sagamore Hill Baptist Church, on the east side of Fort Worth. Although their paths would never cross when they were young, their destinies were already intertwined: almost thirty years later, the two would become rivals for First Baptist.

In the sixties, just about every Preacher Boy in Texas revered W. A. Criswell. Part thespian, part theologian, and all patriarch, Criswell was a figure of mythic eminence, a brilliant orator with a photographic memory who could quote great stretches of Shakespeare and Browning and then subtly shift gears and explain the Greek meanings of certain biblical words. During one eighteen-year stretch at First Baptist, Criswell preached the Bible all the way through, word by word. Kids in those days called him “the Loudspeaker” because his voice didn’t need a microphone to fill the sanctuary. “You cannot underestimate the impact Dr. Criswell had on the city in his heyday,” says Jimmy Draper, a former associate pastor at the church and now a leading executive with the Southern Baptist Convention. “I’d watch him walk into the Petroleum Club in downtown Dallas and give that big hearty chuckle, and you’d see all these corporate leaders, even those who were Jewish, just swoon as if they were Jell-O.”

On Sunday mornings, Gregory would borrow his dad’s 1955 Oldsmobile 88 and drive to Dallas to hear Criswell. He’d sit awestruck in the back row, never mustering the courage to meet the mighty minister. When O. S. Hawkins came to First Baptist as a teenager, he not only met Criswell but also made such an impression that Criswell wrote him a letter the next week, predicting that the Lord had a great future for him.

In the mid-sixties at Baylor University in Waco, where many of the state’s most dashing Preacher Boys gathered, Gregory was a kind of social outcast, a somewhat sepulchral figure who was physically incapable of playing that staple activity of Baptist youth: Ping-Pong. During Baylor’s mandatory swimming classes, he tended to sink to the bottom, leading to speculation that he might drown if he ever attempted to give a new convert a full-immersion baptism. Gregory admits he had “no real teenage or young-adult life.” He was always studying. At Baylor he double-majored in religion and Greek with a minor in history. “When the young man arrived here as a freshman,” recalls Glenn O. Hilburn, the chairman of Baylor’s department of religion, “he had probably the most extensive vocabulary of any student that I had ever taught. It was so extensive that I confess that many times, after a class with him, I would have to go to the Webster’s unabridged dictionary to find out what he was talking about. ”

Gregory hardly seemed the type to become a famous preacher. But in 1968, word spread among the religion students that Gregory, then a junior, had been offered the position of pastor at Waco’s Edgefield Baptist. Although the church was tiny (no more than 45 members), for the church deacons to ask an undergraduate—and the school nerd at that—to be pastor was unheard of. “The students couldn’t believe it,” says Gary Waller, who teaches education and administration at Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary and has known Gregory since they were classmates in high school. “And then they went to see him. And there they heard the voice. And they thought, ‘What on earth has happened?’”

Although Gregory had never taken elocution lessons, he spoke with a stunning, golden voice, the sound like the deep notes of a French horn. “I have no idea where the voice came from,” he says, “but I felt I had an obligation to cultivate the gift.” He spent hours in the library leafing through the Reader’s Guide to Periodical Literature, hunting down just the right modern-day allusions from magazines to use in his sermons. And he’d create such beautiful portraits with words that an audience would look at this sad-faced student in the pulpit and find themselves in tears. “We can turn to Him in the midst of doubt and despair and say, ‘Vindicate me,’ ” Gregory once preached. “And as we know from the psalms, nighttime will become daybreak, and the minor key shall become the major chord.” He would finish his sermons, a little flushed and panting, and he’d just stand there, looking around with a sense of wonder because people were actually listening.

In 1970, when Gregory graduated from Baylor and was ready to head off to Southwestern Seminary in Fort Worth, Edgefield had nearly tripled in membership. By then, Gregory had married his high school sweetheart, Linda, who is thirteen months older. They had fallen in love back at Connell Baptist, when both worked on the church youth newsletter. She was deeply spiritual, highly dedicated to the Baptist church, brunette—“The perfect minister’s wife,” says Gregory’s sister, Margaret Forbes. One of Gregory’s most prized wedding gifts was W. A. Criswell’s five-volume series on the Book of Revelation.

He was a star at seminary. He also quickly found another small church, in the tiny town of Acton, west of Fort Worth. In no time, attendance increased from 90 members to 180. But in his second year at the Acton church, Joel Gregory did something that would, much later, become one of the most analyzed events of his career. On a Wednesday night service in 1971, the 22-year-old Gregory stood up and shocked the congregation by announcing his resignation. He gave no further explanation. He walked out the door, loaded his possessions into a small truck, and drove away.

It’s not unusual for a pastor to suffer from burnout: One survey found that 28 percent of the 62,000 Southern Baptist pastors in this country have quit or seriously considered quitting. Gregory, too, says his sudden resignation in Acton was simply the result of overwork. “I was worn to a frazzle,” he says, “driving back and forth to the seminary and then having to drive to hospitals everywhere. I never felt I had enough time to work on my sermons. Finally, I just wanted to sleep and not get up.”

But it’s likely that what Gregory went through was far more severe than fatigue. After he quit at Acton, he began flunking his exams at the seminary, and he considered dropping out of the ministry altogether. He started selling encyclopedias door to door. In the book he wrote in 1987, Growing Pains of the Soul, Gregory admits that he was deeply depressed during the Acton days. He writes, “I began to imagine rejection—even from the people I was working so hard to help. Looking back, I can see my depression was caused by that seeming rejection. ”

Although Gregory doesn’t mention his old bout of depression or his corresponding fears of rejection in his new book about his departure from First Baptist, the subject has never been far from his mind. In another 1987 book, Southern Baptist Preaching Today, a compilation of the favorite sermons of the most-noted living Southern Baptist preachers, W. A. Criswell chose as his sermon a stirring message about biblical inerrancy called “The Preservation of the Word of God,” and O. S. Hawkins offered the positive salvation message, “All Things New.” Gregory’s choice was a sermon he had once preached in Fort Worth to a meeting of ministers: “When God’s Servant is Depressed.” It is unquestionably the most moving and personal sermon in the book. In it, Gregory says, “So many of God’s greatest men were, at critical moments of their lives, depressed.” He includes Moses, Job, Jonah—and, of course, Jeremiah, one of Gregory’s favorite Old Testament prophets, who in chapter twenty cries a near-blasphemous prayer: “O Lord, you deceived me, and I was deceived; You overpowered me and prevailed. I am ridiculed all day long: everyone mocks me.”

Gregory, in his sermon to the other ministers, proclaims, “Ere some of you finish this year of service, the dark shadow is going to fall across your hearts. . . . You may experience rejection from peers; you may experience rejection from those above you. You may experience it even from those who love you and have pledged to share a life of ministry with you. Whenever you experience rejection and are depressed about it, you are sitting where Jeremiah sat.”

To a large degree, the discussion that goes on today about Gregory among his friends and professional associates is a discussion about his emotional state of being—or what pastors like to call “a man’s soul.” Why would Gregory continue in his later sermons to refer to the Acton experience? Was it so profoundly unsettling, this near-physical collapse from depression, that he could never shake the memory of it? Or was this brilliant, highly sensitive young man plagued by the suspicion that as hard as he worked to earn God’s blessing, it was still not good enough? Was he worried that people would see through the voice and the skillfully crafted sermons and realize that he was still the awkward, insecure kid from Connell Baptist? “I think Joel has always been striving to achieve a sense of adequacy that he never had,” says Baylor University president Herbert Reynolds, who has known Gregory since his undergraduate days. “You would not have to sit and talk with him a very long time to see an individual who has, to an uncommon degree, spent most his life wanting to feel good about himself. ”

Gregory, however, says the Acton story is really the story about his ability to fight back. He escaped depression and restored his good name just as Jeremiah did, by continuing to praise God. Gregory had returned apologetically to Acton several months after his resignation and was accepted unanimously by the congregation as pastor. From then on, he pushed himself even harder, as if to prove that he would not falter again.

After receiving his master of divinity degree at the seminary, Gregory went back to Baylor to get a doctorate in divinity. All the while he continued to pastor churches—first at a small church outside of Waco, then at Emanuel Baptist Church in the city, where attendance under his leadership doubled from 220 to 450. In 1977 he moved back to Fort Worth to become pastor at Gambrell Street Baptist Church, just across the street from the seminary, and over a five-year period, attendance shot up from 400 to 1,200.

At Gambrell, many of the seminary professors got to hear him for the first time, and soon they were spreading his name around the country. In 1980 Jimmy Draper, a former associate minister at First Baptist of Dallas, took a chance on Gregory and offered him a spot as one of the featured speakers at the annual conference of Southern Baptist pastors. At the meeting, the pastors watched with barely concealed grins as Gregory walked formally to the podium, his eyes unblinking, his forehead wrinkled as if to show the gravity of the moment. As one pastor would later put it, “He looked as ugly as homemade sin.” Then, after a pause, out came . . . the voice. “From that moment on,” says Draper, “Joel became the most sought-after Baptist speaker for the next ten to twelve years.”

How could something like this not go to a man’s head? Ministers, of course, are not without ego, and surely Gregory, who as a boy had devoured the biographies of Baptist heroes, could picture himself ascending to the upper echelon of American preaching. In 1982 he left Gambrell and took a job as an assistant professor of preaching at the seminary, in part because it allowed him to preach around the country on weekends. Then, in 1983, the phone rang. It was W. A. Criswell asking him to deliver a series of sermons at First Baptist’s Sunday night services. Looking for the man who would someday follow in his footsteps, Criswell had started bringing in pastors from around the country to preach on Sunday nights. The time had come to study the young Joel Gregory.

At this moment, some say, Gregory began to change, capitulating to an ambition to take the stage with Criswell and be anointed as his successor. It is a difficult charge for him to deny. As he has written in his new book, “For generations of Baptist preachers, the magnetism of First Baptist Church of Dallas evokes something in the spiritual realm akin to sexual lust in another realm.” He was consumed by Criswell. He had read many of Criswell’s 54 books. He knew every detail of Criswell’s history—from his days growing up dirt-poor on a farm in the Texas Panhandle and his first pastorates in small Kentucky churches (where he met his wife, Betty, a church pianist) to a church in Muskogee, Oklahoma, where at the age of 34 he received the surprise call to First Baptist.

After Gregory did a series on the New Testament Book of Corinthians, Criswell told the First Baptist deacons, “This is one of the premier if not the premier theologian in the Southern Baptist Convention.” For Gregory, such a comment meant only one thing: He had a shot at First Baptist. He pushed himself harder, taking the job in 1985 as pastor of the large Travis Avenue Baptist Church of Fort Worth, increasing its membership from 6,500 to more than 8,000. He drove his staff to find new members. He spent Saturdays, his one day off, dropping in on people who had visited the church, urging them to join. He became the Baptist Hour speaker on five hundred radio stations every Sunday. He persuaded the Travis Avenue deacons to buy television time to broadcast the Sunday services. Gregory started wearing contact lenses so the television lights wouldn’t reflect off his thick glasses when he preached. Although at the 1988 annual Southern Baptist Convention he preached what is acknowledged to be one of the most famous sermons in Southern Baptist history—a call for reconciliation between the moderates and the fundamentalists who were fighting over biblical inerrancy—he was already aligning himself with the fundamentalists, which some Baptist leaders now say was a move calculated to impress the hierarchy at First Baptist.

If any pastors had been truly close to him, they might have sensed that burnout was approaching again. He was so busy that he hardly saw his wife or his two sons, who were getting into their teenage years. He and Linda were drifting apart. Linda, who is invariably described as intelligent, giving, and loyal by church members, will not comment publicly about their marriage. But a clue to her emotional state during those days might be that she taught a Sunday school class at Travis Avenue Baptist for wives whose husbands did not come to church—for women whose husbands were not there.

In 1990, while in Boston for a speaking engagement, Gregory happened across a law school fair, where he impulsively bought a study manual for the Law School Admission Test. He studied it on the flight back to Texas. Once again, he was thinking about giving up his pastoral career. Then the news broke that First Baptist had formed a search committee to find a new pastor.

For a while, Gregory thought he was out of the running. Criswell had announced to the congregation that while on vacation in London, he had been awakened at three in the morning with a vision from God. “The Lord spoke to me in my heart,” he says, recalling that day, “and told me who He wanted to come here to be pastor of this church: O. S. Hawkins.” After successfully serving churches in Oklahoma, Hawkins had moved in 1978 to First Baptist Church of Fort Lauderdale, Florida, a dying downtown church, and pushed attendance there from 2,000 to more than 10,000. Such success had vaulted his name into the front ranks of Baptist pastors. While he certainly didn’t have Gregory’s preaching skill, the distinguished-looking Hawkins did possess Criswell’s charm and affability.

But this time, the old leader wasn’t going to wield his power over the church. Throughout the years, Criswell had had his share of fights with several deacons, a few of them prominent downtown lawyers, who had grown weary of his dictatorial moves. Enough deacons agreed that Baptist tradition dictated that the church membership should find its next pastor and not rubber-stamp the wishes of the previous pastor.

A 22-member search committee was formed that included everyone from Ruth Hunt to the owner of the well-known Highland Park Cafeteria. Spending hundreds of thousands of dollars of church money, the committee spent weeks traveling the country to hear preachers. After the first cut, Gregory and Hawkins were high on the list. The committee was also high on James Merritt, a preacher from Snellville, Georgia, outside of Atlanta, until he said he wanted to know, in writing, the date Criswell planned to fully retire from the church. The Criswell loyalists on the committee considered him impudent and blackballed him. As the months wore on, tensions got higher. There were a handful on the committee who wouldn’t even consider Hawkins, simply because he was Criswell’s man. Two men, both lawyers, nearly came to blows over Hawkins. Two other members resigned from the committee in disgust, one leaving the church altogether. The search process got so drawn out that there was even a skit at the national Southern Baptist Convention lampooning the committee and teasing Gregory and Hawkins.

By the end, after more than two years of bickering, there was only one compromise choice left: Joel Gregory. Hungry to get the job and not wishing to jeopardize his chances, Gregory had never asked the committee about Criswell’s role at the church in his new title, senior pastor. Many First Baptist staffers and close friends say they took Gregory aside before he accepted the job and told him that it wouldn’t be easy as pastor of First Baptist for the first few years, that Criswell would have trouble letting go of the church that he’d spent so many years building, and that Criswell would have even more trouble accepting up-to-date programs implemented by a new pastor. Gregory was also warned about the fiercely protective Betty Criswell, who had never taken kindly to the new men who had come in as possible replacements for her husband. For decades she had taught a Sunday school class for men and women that had become known as “the church within the church.” The powerful class had more than six hundred members, who as a group gave the church between $1 million and $1.5 million each year. Although Criswell, as an inerrantist, was required to literally follow the words of I Timothy 2:11–12, which forbids a woman to teach or usurp authority over a man, he had allowed his wife free reign as the first lady of the church—and few were willing to cross her.

But there was little discord on November 25, 1990, when the church members, according to one deacon there, “exploded onto their feet” in the sanctuary when asked to approve the selection of Joel Gregory as only the third pastor in their history. Criswell told the packed house, “Even Dr. Gregory’s name, Joel—Jehova of God—honors the Lord.” Gregory, his lower lip trembling, his eyes like hyphens, seemed overwhelmed. He didn’t smile once. He went to the pulpit and told the crowd that ever since he was a boy he had wanted to be able to preach like W. A. Criswell. But, as if unconsciously preparing First Baptist for what was to come, he told them he could never be another Criswell. “Be under no illusions about this Baptist preacher,” he said about himself, tears filling his eyes. “I have a treasure—the gospel of Jesus Christ. But I have it in a clay pot. A jar of mud.”

No pastor at First Baptist remains with a jar of mud for long. Gregory was given a $165,000 salary, along with a $10,000 signing bonus. He purchased a $465,000 home next to the ninth fairway of the Lakewood Country Club in east Dallas. Church volunteers landscaped his yard, and the church provided him with a personal computer and laptop and a cellular phone. He received free memberships to Lakewood Country Club and the Petroleum Club. When he and Linda would throw a dinner party at home for church members, the church kitchen staff would cater the affair, and church security officers would arrive to valet-park the guests’ cars. The church built Gregory an $80,000 office at the church that included bulletproof glass in the windows and an escape door disguised as a wall panel to allow Gregory to slip away from his office undetected. Joel Gregory had moved right into big-time religion.

Those who have felt truly close to Gregory—and there are maybe a handful—remain mystified by what happened over the next two years at First Baptist. During his first months, Gregory spent his days praising Criswell. He turned his weekly column in the church newsletter into a gushy hymn of adulation for the senior pastor. (“For me, he has always been there,” Gregory wrote. “Like an Everest towering over the landscape, he was rarely out of sight.”) He watched videotapes of Criswell serving Communion so he could do it exactly the same way. He bought a white suit and a $250 pair of white shoes because Criswell always wore a white suit to Sunday services in the summer. Standing stiffly beside the old man at those services, Gregory looked like a pale glass of milk.

But they seemed to work as a team—Criswell, the titan under that shock of white hair, and the pinch-faced Gregory. Initially, Gregory spoke at the early eight-fifteen service, then Criswell spoke at the eleven o’clock service, the glory hour for a First Baptist pastor, the one shown on local and cable television. Within a few months, they were alternating services.

As more months passed, however, Gregory became convinced that Criswell and his wife were out to prevent him from taking over his rightful responsibilities as pastor. In his book, Gregory writes that he was misled about how long Criswell would stay around. He says that just before accepting the position at First Baptist, he visited with Criswell, who told him that he would remain preaching at the church for “a few months” and then devote more time to First Baptist’s four-year Criswell College. In a rare burst of anger, Criswell replies in an interview that it is “absolutely not true” he told Gregory he would step aside in a few months. “That’s just silly,” he says. Gregory, in turn, says that Criswell is the type of man who would “invent reality by the yard.”

To some in the church, Gregory grew more paranoid of the Criswells by the day. He thought Criswell’s jokes about Fort Worth, which the old man had been saying for years, were put-downs directed at him. It bothered Gregory that Criswell’s secretary still answered the phone with the greeting “pastor’s office” instead of the more accurate “senior pastor’s office.” He suspected Criswell’s friends of secretly approaching visitors who were planning to join the church during Gregory’s Sunday service and having them switch to Criswell’s service, so it would look like the old man was getting more people to “walk the aisle.”

After half a century of life with the backslapping Criswell, who would amble up to people whose names he had forgotten and greet them like old friends, it had to be difficult for church members to relate to the professorial Gregory, who sometimes would forget to say hello to those he passed in the hallways. Criswell says that after six months of increased attendance under Gregory, the crowds had begun to drop—a surprise, considering Gregory’s reputation for packing the house. Gregory counters that the problem with church attendance was due solely to Criswell’s remaining at the church and not giving up his preaching assignments. “People at First Baptist wanted to see a new face in the pulpit to know that a real transition was taking place,” he says.

Comments like that make some church members wonder if Gregory’s resentment toward Criswell was really a sign of runaway ambition. Obsessed with his own place in Baptist history, aching to prove his abilities, caught up with the materialistic trappings of the church, the once mild-mannered Bible scholar felt a need to push Criswell off the stage so he could finally step out of his shadow. A few others, however, have speculated that Gregory had begun to feel overwhelmed by the job at First Baptist, which requires the skills of a Fortune 500 CEO. To save face, according to this theory, he tried to pin his problems on Criswell. “In my opinion, Joel was scared that if he went down as a failure, he would not get another opportunity with a big church,” says real estate investor Jack Pogue, Criswell’s closest friend.

Gregory contends that a leading church deacon named Ed Rawls, a prominent North Dallas architect, informed him that Criswell, while on a trip to the Holy Land, had begun talking about taking the church over again because it was not growing fast enough under Gregory. Rawls says Gregory’s version of events is a fabrication. Criswell only said he hoped to see increased membership, says Rawls, and never mentioned taking back the church. (Criswell, too, says he never suggested such a thing.)

When pressed about those days, Gregory admits that Criswell was always cordial to him during his time there; he never publicly criticized him and never publicly tried to get Gregory to back off on an issue. He also acknowledges that no deacons, not even those who were longtime Criswell friends, challenged Gregory on anything he proposed. Gregory has painted himself into a corner. If no one was against him in church meetings and if Criswell was not openly second-guessing him, then what exactly was the crisis? Gregory has no satisfactory answer.

In some ways, Gregory was experiencing the very thing at First Baptist that he had written about years earlier in Growing Pains of the Soul, when he described his unhappy days as a depressed young minister in acton. “We begin to react by being irrationally unfair to those around us,” he wrote. “And that’s even more depressing, especially to those closest to us.” Exhausted from the nonstop work, feeling unappreciated by the very people he had tried so hard to impress, certainly sensing rejection by the man whom he considered his mentor, Gregory withdrew. He spent more time alone at his home office. On Saturdays he’d drive to NorthPark mall and just walk among people who did not know him.

In August 1992, when Criswell talked about staying on at the church until 1994 in order to celebrate his fiftieth anniversary there, Gregory seemed devastated. Although other deacons said Criswell had never kept secret his desire to stay on at the church for his fiftieth year, Gregory told the deacons he thought two more years with Criswell was too long. Finally, on September 23, Criswell went to Gregory’s office to ask why he seemed so cheerless. It would be their last meeting. Gregory said he wanted both Criswell and Betty to stop criticizing him, he wanted Criswell to move out of the church office, and he wanted to preach all of the eleven o’clock Sunday services. According to Criswell’s version of the meeting, he told Gregory that he was already making plans to move out of his church office and that he’d abide by any preaching schedule Gregory wanted. According to Gregory’s version, Criswell made only one specific promise: to stop Betty’s criticism. Right then, says Gregory, he decided to leave. He did not want to go through a power struggle with Criswell. As he writes in his book, “I was not about to sacrifice myself in a no-win confrontation that would brutalize me, enrage Mrs. Criswell, make W.A. a martyr, raise hell in the church, make headlines in the papers, and polarize the entire conservative wing of a sixteen-million-member denomination. ”

But with his Wednesday night resignation, Gregory did exactly that. He says he hired private detectives in case angry members tried to detain him. He needn’t have worried. As he read his 289-word letter of resignation, the crowd sat in disbelief. Criswell was so dumbfounded he couldn’t move. But even as Gregory was announcing that he could no longer work with Criswell at the church, he still couldn’t help but praise him one more time. “I have and do express love and veneration for Dr. Criswell,” he said. What he did not say was that Criswell’s friend Jack Pogue had already arranged for movers to take Criswell’s office furniture out of the church that Saturday—something that Pogue says Gregory knew all along.

For more than six months Gregory remained in Dallas, living with his family in a borrowed townhouse. He barely went outside. He seldom opened his Bible. He read Tom Clancy, John Grisham, Michael Crichton. Gregory says that after years of delivering formal prayers, his prayers in that Dallas townhouse would begin, “Oh, God, this is the biggest mess I’ve ever been in . . .” and then he’d stop.

He tried to get closer to his two sons, both of whom had gone through their own problems during his days at First Baptist. They had attended the First Baptist Academy and chafed under its strictness. Grant, his artistic elder son, angered the principal because he drew a mural in the style of Picasso on the art room wall (the principal was against it because Picasso was “un-Christian”). Garrett, Gregory’s younger son, was suspended from the academy because he allegedly spat on a bulletin board. (Grant is now an art student at Texas Christian University; Garrett, who studies guitar, is finishing high school in Fort Worth.)

Gregory also tried to get closer to Linda. But by April 1993, they had separated, eventually releasing a peculiar statement to the media saying the split had come because of “long-term differences in the understanding of our relative roles in marriage”; their divorce became final in December 1993. Gregory says the tension caused by the First Baptist resignation was the catalyst for their separation, but First Baptist members, along with members of Gregory’s former churches, were outraged that Gregory would leave the woman who had stuck by him through everything. “She stayed and paid the price for watching her husband succumb to ambition,” says one man who knows them both well. According to her friends, Linda, now a schoolteacher living in the Dallas–Fort Worth area, has been so devastated by the upheaval in her life that she has yet to go back to a Baptist church. Still, says one who knows her, Linda has said, “Joel deserves his happiness, whatever that may be.”

Gregory moved on to a Fort Worth apartment complex filled mostly with young singles. He put a television set on the floor and a print of Tom Landry, the deposed Dallas Cowboys coach, on a wall. He drove to Jack-In-The-Box to buy his dinner. He saw an ad for a “memorial estate counselor” in the classified ads and went to a training class. His downfall seemed to take on biblical proportions. Joel Gregory had given up the Baptist kingdom, where each week he preached on everlasting life, in order to sell funeral plots.

Perhaps it was because his resignation was so bizarre that the adultery rumors got started. It was easier to understand Gregory’s fall from grace if another woman had been involved. In part, the rumors helped First Baptist members—a proud tribe that doesn’t take kindly to being abandoned—to break with Gregory for good. Many First Baptist members spread the story that a woman in a dress was waiting for Gregory on the sidewalks outside the church the night he resigned.

The most dominant rumor was that Gregory had been having an affair with Sherry Lemmons, a pretty, blond, soft-spoken former member of Travis Avenue Baptist in Fort Worth. Gregory and Lemmons say that when they were both there in the late eighties, they were, at best, casual acquaintances. “Believe me,” says a prominent layman at Travis, “there was never any suggestion of any inappropriate act by Joel Gregory in his years at Travis. If there had been one tiny rumor, I would have heard about it. ”

After Gregory moved to Dallas, Lemmons says, she began going through marital troubles, and she became separated in the summer of 1991. She had three children to support and needed a job, so she called Gregory. He found her part-time work for three weeks at First Baptist, filling in as a secretary for the church administrator, then working for Gregory himself. Was it possible that the two, back then, might have started falling in love? “To be honest,” says the 41-year-old Lemmons, “I was so wrapped up in my own twenty-year marriage coming to an end that I didn’t see Joel as anything but a pastor. It took a long time before I could even imagine having a date. ”

Gregory and Lemmons say they saw each other only one other time—at a First Baptist Christmas concert—between the time she worked for him in 1991 and the time he moved to Fort Worth in 1993. They say their first date, which included her children, was to a Vince Gill country music concert on the July Fourth weekend of 1993. Gregory says it was his first outing with a woman since his separation from Linda three months before. Gregory challenges anyone to prove otherwise.

Gregory says he could have moved to Southern California, where he had a couple of job offers to preach and teach, “but that would have made me look as guilty as sin. That is the stereotypical thing a preacher does when he gets in some kind of, quote, woman trouble.” So he remained a pariah in Fort Worth. When he went to Southwestern Seminary, his old stomping grounds, he’d hear students whispering. When he went to dinner with Lemmons, restaurant patrons would put down their forks and stare. They saw a man acting positively giggly, finally going through the adolescence that he had never allowed himself to have.

Last June he rented a limousine, picked Sherry Lemmons up at her home, and took her to the downtown Forth Worth Club, where he had rented a private dining room. There were a dozen roses on the dinner table. A harpist he had hired for the evening was playing soft music in a corner. Gregory pulled out a ring and asked Lemmons to marry him. Two months later they held their wedding at Fort Worth’s Thistle Hill mansion. At the reception, they drank champagne. They honeymooned in Jamaica. Then they came back to Fort Worth, where Joel Gregory put on his dark suit and lace-up shoes, and went out to ring fifty doorbells.

In 1993 a search committee was formed at First Baptist to a find a new pastor. This time it consisted of only eight members, and after a perfunctory search, the committee nominated, of course, O. S. Hawkins. God’s—or W. A. Criswell’s—will had been done. Hawkins, who arrived at the church in late 1993, refuses to discuss the Gregory story in public. All he says about the upcoming book is, “This too shall pass.” But he has to be grateful to Gregory for one thing: To avoid any potential problems with Hawkins, Criswell made sure to scale back his life at the church. He goes to no meetings and rarely preaches, except when Hawkins asks him to. He and Hawkins seem to enjoy the dickens out of one another. Criswell loves the way Hawkins teases him in front of the congregation about his white summer suits. Hawkins, incidentally, makes a point of wearing dark suits.

Criswell, who has withstood more controversies over the years than he can count, says he has moved far beyond the Gregory years. The two have not spoken since Gregory left. “What’s happening is between him and God,” says the great one, his ageless voice ringing like the clash of bronze cymbals. But then he pauses. “Oh, my, my. This is the man who I thought, back yonder, was the most marvelous pulpiteer in the church.”

As for Gregory, he just sighs at Criswell’s allegation that he is no longer a Christian. He says his conservative theology is still intact, but for now, he is wary of churches, especially people in churches who in the name of God can destroy someone’s reputation. He says he hasn’t watched First Baptist on television or listened to a service on the radio since he left. He has attended other churches around Fort Worth a couple of dozen times, but he doesn’t know if he’ll join one. “Asking me if I’m going to get involved in another church right now is like asking a man who just got washed up on the shore after nearly drowning if he wants to go back out for a swim. ”

If Gregory is experiencing the pangs of humility—a recognition of what his self-consuming drive to be a great preacher did to his life—it is not obvious in his book. He is intent on redeeming himself, proving that he was victimized by what he labels “a vintage Criswellian ploy.” He writes at length about his accomplishments. When he comes to the section about his move to First Baptist, he writes, “No hour in American religious culture could be more laden with destiny.” When he writes about his resignation, he compares it with the abdication of Edward VIII from the throne of England. Gregory could have come up with a better example: Edward VIII gave up the throne for a woman.

When a visitor asks if he is happy with the job he has now, Gregory gets up from his couch and grabs a wooden plaque on the mantel. It reads “Joel Gregory, 1993 Greenwood-Mount Olivet Rookie of the Year.” He says proudly that he made $45,000 last year. There is a silence, and suddenly, his eyes fill with tears. He looks away. “Yes, I know what people are saying, that I’m throwing away the gift God has given me …” His heavy ecclesiastical voice is gone—the voice that for so many years hid all his uncertainties. He opens his palms and makes the same gesture that he sometimes used to make in the pulpit—only this time, it is the empty palm of a man with no speech to make. It is a defenseless gesture.

“So what do you do with that gift God gave you when you were sixteen years old?” he is asked.

“Oh, you know, I preached for twenty-eight years. Maybe it’s time to see how God wants me to serve Him now. Maybe it’s time to find another voice. ”

“But can you really give the old voice up? Do you know what the new voice will be?”

Gregory seems unsure of what to say. A few weeks before he left First Baptist, he had preached his last sermon, one he had titled “Escape Despair Now.” Gregory told his fellow Baptists that the beloved Old Testament figure, King David, battled his despair by remembering his better days, when he led multitudes at the temple of God. “When I am down,” Gregory preached, his voice full and firm, “I, like the Psalmist, can say I remember when I went up to the house of God.”

But now, Joel Gregory is far from any house of God, and far from the life of King David. Instead he remains haunted by the tortured prophet, Jeremiah. For now, he is dwelling in what Jeremiah called the land of deep darkness—still wondering what his new voice will be. “Sometimes,” he finally says to his visitor, “when you can’t feel God subjectively, when you aren’t sure where God is, you must wait in silence.”

He caresses the edges of his funeral home plaque. He looks out the window. And for a long time, he is silent.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Baptists

- Dallas