This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Juan jumped off a freight car in San Antonio with his older brother Javier at sunup on a Sunday. The young Mexicans had traveled night and day for two weeks and had covered much of South Texas on foot. The Border Patrol had caught them twice, but on this third attempt to enter Texas, Juan and Javier succeeded. Early on Monday Javier went back to his job with a roofing company. By Tuesday he had arranged a Social Security number for Juan as well as a job as a roofer’s helper with the same outfit. At 7:00 a.m. on Wednesday Juan began work on his first job in the United States. Ascensión, a sixty-year-old man dressed in clean gray work clothes and a white hard hat, took Juan in hand that first day.

“Over here,” Ascensión said, leading the way, “we have the chapapote.” Ninety-pound cylinders of tar lay stacked on the ground, wrapped in brown paper like huge pieces of taffy. Ascensión rolled one of them to the tar vat, slit the paper down the side with a knife, and lifted it up to shoulder height to lower it into the smoking vat. They watched it sink and begin to melt like a cube of ice. “Put in five,” Ascensión said, holding up five fingers in his heavy gloves before taking the gloves off and handing them to Juan. Juan took them and started for the chapapote. “Mario,” Ascensión called Juan back, “when you put the chapapote in”—he rolled up his sleeve—“don’t drop it!” He held out the inside of his forearm to show Juan a topographic map of white scar tissue. “It’s hot.” Ascensión smiled with meaning.

Juan grimaced and started back toward the chapapote. Late the day before, he had become Mario when Javier came in from work with a pale-blue, laminated card that said Mario Saenz and gave a place and date of birth and, most important, a Social Security number. The card was forged but the Social Security number was authentic, so that an account existed for Juan’s earnings. “At work, call yourself Mario,” Javier had told him. “I’m Francisco or Frank. I’m not your brother. Don’t forget and call me Javier.”

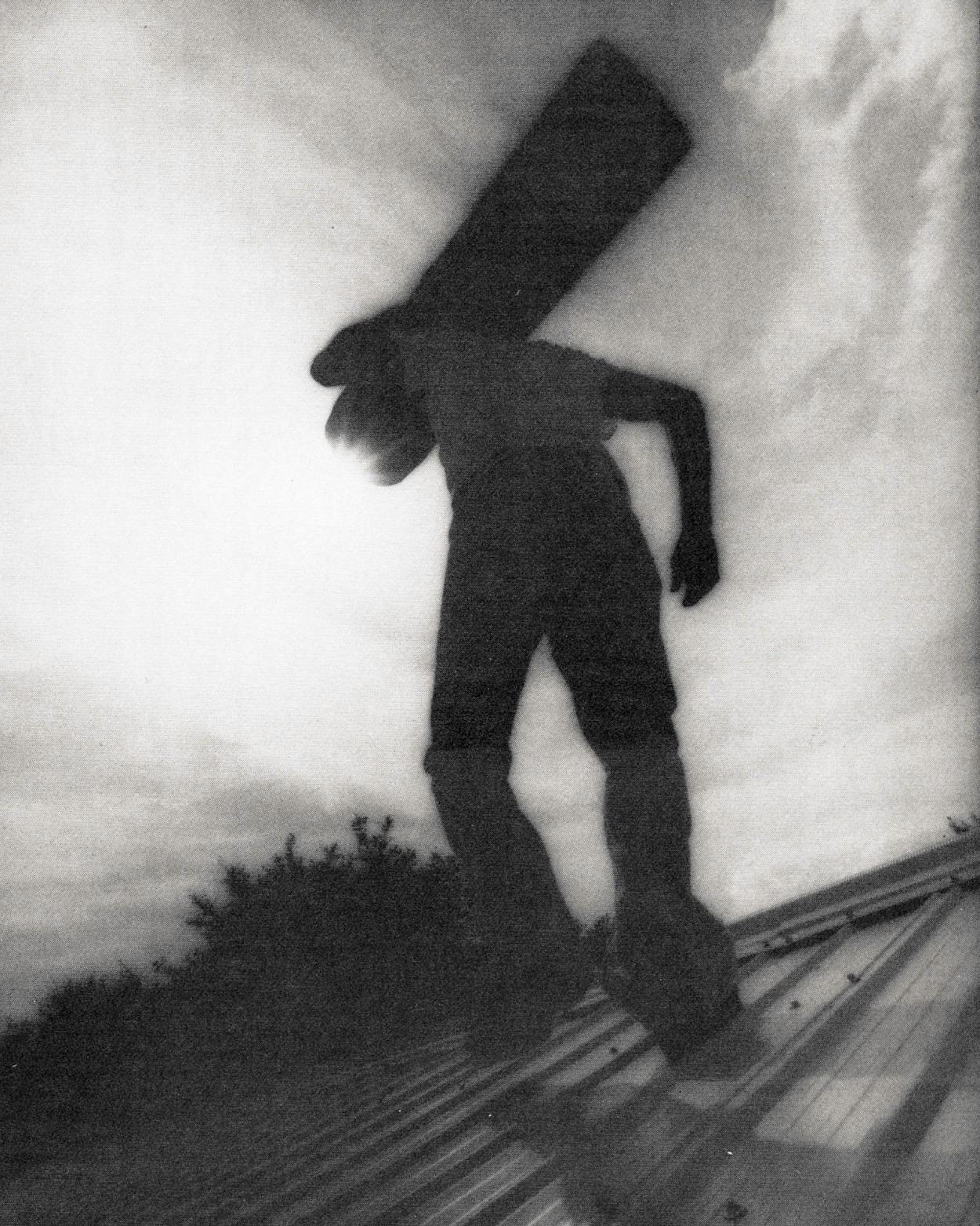

Juan put on the gloves and rolled one of the cylinders of tar to the vat. At 130 pounds, Juan wasn’t much heavier than his load. He cut off the paper, got a firm grip, and heaved the cylinder to the edge of the vat. Slowly he lowered the opposite end before letting go and jumping back. The cylinder slid in with a minimal splash. Juan stepped forward to watch it settle next to the other cylinder. Through the smoke rising about the tar, he could see Javier and another man on the roof talking and laughing.

When Juan finished, Ascensión told him to go up on the roof and help clean up. It had to be swept before new rolls of asphalt paper could be put down. As he pushed a broom, Juan watched Javier, who was measuring, then cutting pieces of new lumber with an electric saw. He wore a carpenter’s belt and was in charge of replacing old gravel guards, flashings, and parts of the roof where the boards beneath were rotten. Juan swept several piles of gravel and scraps together, scooped them up in a large shovel, and dropped them into the dump truck that had been backed up to the edge of the house. It was hot on the roof; the sky above San Antonio was a glaring carbon-monoxide gray. Below, the racket of the pump’s gasoline engine joined the roar of the kerosene burners. Juan watched an American come out of the house next door, get into a brown sports car, and drive away. In every direction he could see flat gravel roofs like the one he stood on.

“Mario!” Ascensión poked his head over the edge of the roof. “Come with me,” he said and disappeared. Juan climbed down the ladder and followed Ascensión to the pickup where he was securing a large metal drum to a small hand truck. “Take this up on the roof,” Ascensión directed. Juan rolled the hand truck to the ladder and dragged it up behind him. Ascensión followed with a large mop and a five-gallon bucket. “Ready?” Ascensión called to the foreman and his assistant.

“Ready,” they called back. Both the foreman and his assistant were large men made larger by their hard hats and heavy, thick-soled boots. The foreman’s enormous muttonchop sideburns and moustache gave him a fierce look.

Ascensión and Juan rolled the tub to the pipe that was connected to the vat of tar, positioned the tub beneath, and pulled the rope. The tar that gushed out was preceded by and enveloped in smoke so that the tub appeared to be filling with nothing more than hot vapor. When it approached the rim, the black liquid came into view, and Ascensión let go of the rope. He rolled the tub to the far end of the roof and gave the foreman the mop. While his assistant brought a large roll of black paper from the front of the roof, the foreman dipped the mop in the tub as if testing the tar.

“Mira,” Ascensión explained to Juan, “when they want more tar, fill this bucket.” He held up the five-gallon bucket. “Take it and pour it into the tub. When they want paper, get paper. Don’t get in the way of the mop and don’t spill tar on yourself.” Juan nodded earnestly, pulled on his heavy gloves, and waited by the pipe. The foreman lifted the heavy, steaming mop out of the tub and made a fast sweep at the edge of the roof, leaving three pools of boiling tar and spreading a cloud of smoke through the air. When his assistant rolled the asphalt paper over the tar, it sizzled through to the surface. Juan watched their progress until the foreman shouted, “¡Chapapote!” Then he filled the bucket, grabbed its handle, and, leaning away from its weight, staggered across the roof to pour the tar into the tub. “¡Papel!” the assistant shouted as soon as Juan had returned to the pipe. Juan rushed to the front of the house, swung a sixty-pound roll of asphalt paper onto his shoulder, and, stepping fast, carried it to the men.

The strips of asphalt rolled across the roof, the black surface collecting the heat, the pools of hot tar glittering in the sun. Not talking, sweating through the gray uniforms, the men moved within a cloud of smoke. Javier, Juan realized, was watching him. But each time Juan looked in his direction, Javier looked away. Since they had gotten out of the car that morning, Javier had shown no sign that he knew Juan.

When they had covered the roof with one layer of the paper, they started again, overlapping the rolls to build up three layers. Juan’s knees began to shake as he went from paper to tar, and a continuous stream of sweat poured out of his hard hat into his eyes. Other than the heat radiating against his right leg when he carried the bucket, the potentially dangerous slap of the mop, and the weight of the rolls of asphalt, Juan was aware of nothing but “¡Chapapote! ¡Papel!”

After the last roll of paper, they broke for lunch. Juan climbed down the ladder at the front of the house, stopped for a drink of water from the tar-splattered cup that was tied with a string to the water cooler, and fell supine in the shade to wait for Javier. Ascensión had already gotten his black metal lunch box and was carefully peeling a cucumber.

Javier walked up from the truck with the lunch kit, dropped a foil package next to Juan, and, without a word, walked off and sat down alone. Bewildered, Juan looked at him, then slowly opened the package of tacos. He ate and lay back down with his hard hat over his face. When he woke, the men were already on the roof, and he had the sad feeling of not knowing where he was.

The afternoon went like the morning except that they covered the tar with gravel rather than asphalt paper. Ascensión tended the vat while a large conveyor belt carried the gravel from a dump truck to wheelbarrows on the roof. Javier and another man pushed the wheelbarrows to where the foreman spread the tar that Juan brought in buckets while the foreman’s assistant shoveled. By the time they had finished and packed up all the equipment, it was after five o’clock. Juan rode back to the company headquarters in the pickup with Ascensión. Juan saw Javier go up onto the loading dock and into the room where the crews congregated in the morning, but decided he would wait in the car. He walked out to the parking lot, climbed into the old blue Pontiac, and slumped down to rest. As far as Juan knew, it was the first car anyone in the family had owned. And Javier was the first to learn how to drive.

Javier dropped his lunch box and hard hat through the window into the back seat and got in. He didn’t speak, but he started the car and they drove slowly, springs squeaking, through the affluent neighborhoods of North San Antonio to the downtown section, where the empty streets looked stale in the afternoon glare. They went west on Commerce Street, past the old Farmer’s Market, beneath the expressway, and into West San Antonio. They turned off the main thoroughfare, drove through a freshly paved parking lot, and stopped the car in front of a small frame shack that looked across an alley into the lot. “I’m going to buy food,” Javier said and waited for Juan to get out.

Juan let himself in at the gate of the chain-link fence, crossed the caliche strip of yard, and unlocked the door on a dark room dense with stored heat. He switched on the overhead light, stuck his hand behind the red curtain and Venetian blind to raise the front window and went into the kitchen to open the back door. In the front room, he took the exposed copper ends of a fan’s electric cord and shoved them into a wall socket. The fan began to generate a metallic clang and a slight breeze. Exhausted and hot, he lay down on the warm, lumpy bed and stared first at the pink ceiling, then at a framed picture of a red-lipped woman playing a guitar.

When Javier came in, he took a bag of groceries in to the small table in the kitchen. He pulled loose the strip of black electrical tape that held the refrigerator door closed, emptied the pan of rusty water that dripped out of the small freezing compartment, and stored the food. Walking into the front room, he took off his shirt and pants and hung them along with his other clothes on nails driven into the wall. In the bathroom, avoiding the rotten floorboards beneath the worn linoleum mat, he edged past the toilet and lavatory to climb into the moldy shower stall that doubled as storage for a mop and some rags. He turned on warm water to lather and scrub himself with a knot of sisal, then cold to try to cool off. As he dried himself, sweat broke out on his skin so that he was still wet when he put on the underwear that he stored in the gutted stereo cabinet in the front room. Looking through the front door, he could tell by the slant of light on the parking lot that the sun was going down, and above him the tin roof popped hollowly as the trapped heat diminished. He snapped on the radio—part of a plastic phonograph set—to the local Spanish station, pulled on clean pants and platform shoes, and went into the kitchen.

Juan managed to drag himself off the bed. On the way to the bathroom, he noticed that Javier was spooning gray lard from a jar into a skillet on the stove. A cold pot of boiled potatoes sat on the table among the dirty dishes that had been there since morning. When Juan came out, Javier was tearing the skin off the potatoes. Onions were simmering in the lard. Juan dressed, took the plate of potatoes and onions scrambled with eggs and the glass of punch Javier put out, and ate standing by the door. When he finished, Juan put his empty plate in the kitchen sink, ran water over a rag dipped in detergent, and began to wash the few plastic plates and glasses. Shirtless beneath the raw light bulb, Javier was rolling out tortillas with a glass on the tabletop; perspiration dripped from his face into the white flour.

Juan finished the dishes and went to lie on his edge of the bed. Beneath the blare of the radio, he could hear the thump of a jukebox from the bar across the parking lot, and, staring at the floor, he could see beneath the crust of dirt to the original pattern of green and yellow spots that decorated the cracked and peeling linoleum.

The alarm clock went off, and Juan could hear Javier get up and go in the dark into the bathroom. The toilet flushed, then the light snapped on in the ceiling. Juan squinted at Javier. “What’s wrong? What time is it?”

“Five,” Javier said and pulled on the gray trousers to his uniform.

“Five? Already?”

“Get up. We have to make breakfast, then lunch.” Javier pulled on his shirt and went into the kitchen.

The week passed. Each morning they got up at five to prepare food and eat, went to work at seven, and came home at night in time to eat again, bathe, and sleep until the next day. Javier continued to ignore Juan at work and didn’t speak unless it was necessary. On Friday, Juan learned that the crew worked on Saturdays. On Saturday, Javier told him they were going to work for an independent shingle contractor on Sunday.

By Monday, Juan had begun to drag. Javier’s silence wore on him, and he saw no point to the hard work if there was no prospect of pleasure or at least rest. Resenting Javier, resenting each call for tar or paper, he didn’t realize his feelings showed until Tuesday at lunch. “Keep acting the way you are,” Javier said as he handed Juan his tacos, “and they’ll run you off.” That afternoon Juan saw that the foreman was watching him. Their suspicion hurt his feelings, then made him belligerent. “Let them fire me,” he would say to himself. “I don’t care.”

On Tuesday night Javier disappeared. He bathed, put on a good shirt and trousers, combed his hair carefully, and left in the car. Thinking Javier would come back to make dinner, Juan waited until hunger coerced him into making bread-and-margarine sandwiches. He took the sandwiches and a glass of punch out to the step in front of the house where he sat and listened to the mournful thump of the jukebox rise and fall each time a customer opened the door to La Segunda Cumbia de Paco. In the distance, two red lights tracked up and down the side of a tower topped by a saucer-shaped platform. The platform, Juan noticed, was slowly rotating. It looked strange and made him see how far away from home he was. He thought of his parents and decided to leave as soon as he was paid.

Juan woke when Javier came in, but neither of them spoke. Juan felt better the next day and worked harder. The end was in sight.

Thursday night, Javier again left without explanation. Juan ate, gathered up the pennies on top of the old stereo cabinet, and walked to La Segunda Cumbia to buy a quart of beer. He brought the beer back to the house, where he sat on the front step and watched the tower platform revolve. While he drank, he pondered Javier’s meanness. He finished the beer and, slightly high, went for another. Sitting on the steps again, he began to think of his mother, then thought of his girlfriend. “Ay, Lourdes!” he said, remembering for the first time that he hadn’t said good-bye. He went inside to turn on the radio, a song ended, and after an announcement, a man began singing “El Huerfanito.” Juan listened to the maudlin song about the young orphan and thought of how he had left poor little Lourdes all alone and had barely thought of her. The skin on his cheeks grew tight, the tears ran down his face, and he could taste the salt at the back of his throat easing the lump. “Poor little Lourdes,” he kept saying to himself, and finally he took a black crayon, made a large cross on the wall above his pillow, and wrote her name in bold letters. He put his head on the pillow and felt better until he thought of his other novia, Leti, then got up and wrote her name on the wall next to Lourdes’. He finished the beer and lay back down to think of poor Lourdes and poor Leti. When he woke, he didn’t know if it was night or morning, whether Javier was getting up or going to bed.

“What have you been doing?” Javier stood over the bed, glaring at him. “You’ve gotten drunk. Written on the walls. Acted just as I knew you would.”

Juan scowled at Javier, then turned his face to the wall. The skin around his eyes burned from the tears, and he could still taste the salt.

“What’s wrong with you?” Javier said and took off his shirt. “Do you know how easy you have it? I got you a job, I take you to work. I feed you.” Javier kicked off his shoes. “You have a place to live. What do you want? When I came, I had nothing. No one helped me, I had to rent a room every day, and if I couldn’t find work for the day, I didn’t have a place to sleep or anything to eat.” He stood and stared down at Juan’s back. “Why don’t you grow up and stop being such a baby?”

Juan lay tense, his face to the wall, and refused to answer. “I shouldn’t have brought you,” Javier said in a quieter voice. “I’m too young to raise you.”

Juan rolled over and looked at him. “Don’t worry. I’m going back to Mexico,” he said and turned back to the wall.

The next morning when they left for work, Javier took a pillow from the bed and put it in the car. They didn’t speak, but Juan’s attitude made it clear that he was still angry. At lunch, Javier gave Juan the carne guisada and tortillas he had prepared and sat down on the grass next to him. “Hot, isn’t it?” he said.

“Yes, it’s hot,” Juan said and got up to get a drink of water.

After work when Javier went out to the car, he saw Juan slumped down on the front seat. Rather than going to the driver’s side, he walked around and opened Juan’s door. “What?” Juan demanded and looked up belligerently, as if Javier might be telling him he couldn’t have a ride. Javier reached in his pocket and held out the car keys. “You should probably learn how to drive,” he said.

Juan looked at the keys. “Now?” he asked.

Javier turned down the corners of his mouth to make a serious face and nodded yes.

Juan reached for the keys. “Okay,” he said, resisting the urge to smile.

Javier showed Juan how to move the seat up, gave him the pillow to sit on, and explained the fundamentals. Juan could barely see over the dashboard, his foot just reached the gas pedal, but when he turned the key, the engine started and he felt a surge of triumph. Sitting next to him, Javier demonstrated the automatic transmission and told him that when he steered he must focus on the left front fender to know where he was going. “It’s the other fenders that are difficult,” he warned.

They made slow circles in the parking lot, the car lurching to halts until Juan learned to step gently on the power brakes. After mastering a smooth start and stop, and securing a promise of more lessons, Juan surrendered the steering wheel to Javier. On the way home, Juan was unable to contain his enthusiasm. “Someday, maybe I can drive home,” he said.

“Someday,” Javier agreed.

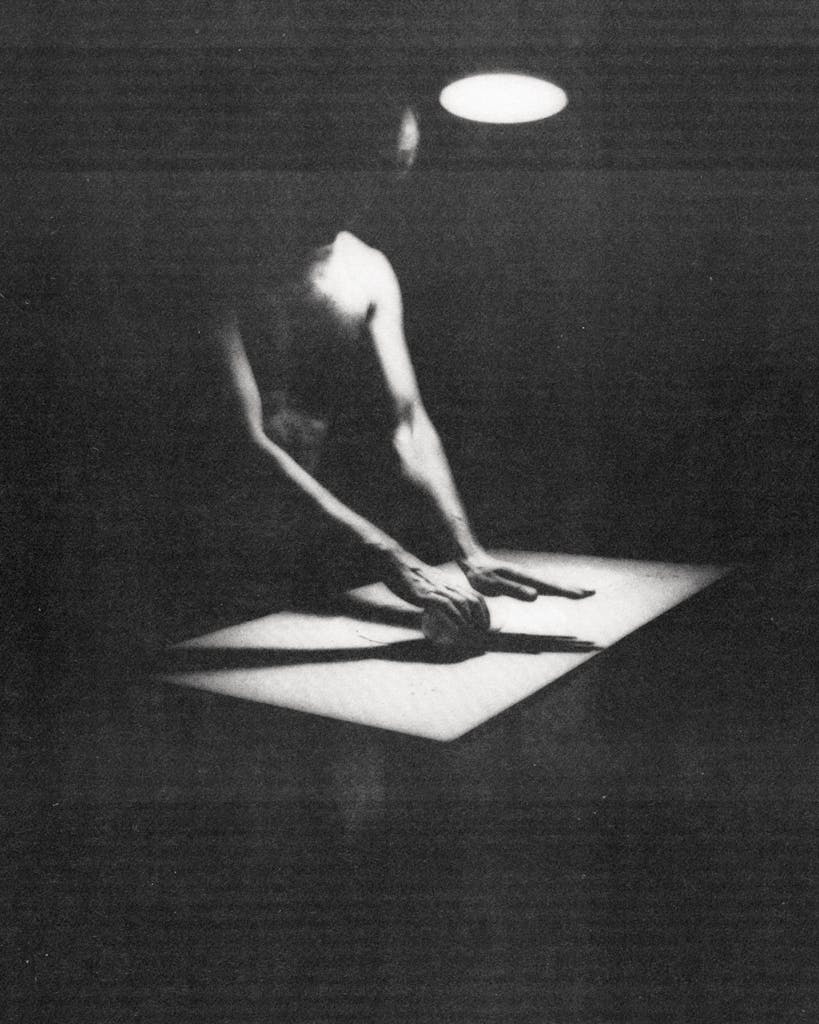

That night, when Javier began to cook supper, Juan offered to help. “Can you make tortillas?” Javier asked.

Juan shook his head.

“I’ll show you. It’s not hard.” Javier got a bowl, mixed flour and water, and worked the dough to the proper consistency. “Make a little ball,” he said, “and once it’s round, roll it out with a glass.” He dusted the tabletop with flour and rolled out the tortilla. Juan watched him make two, then gave it a try. After he had mastered the process, he began to talk, asking about cars, how much they cost, whether Javier could take his car to Mexico, and so on. As soon as Juan had eaten and done the supper dishes, he went out and sat in the car to practice for a few minutes before bed.

That weekend they worked for the company on Saturday and for the independent contractor on Sunday. The contractor, like Juan and Javier, was employed at the roofing company the rest of the week. The contractor took jobs that could be completed on Sunday with the hope of someday building enough business to go on his own. Javier and Juan didn’t earn as much with the contractor as with the company, where they made $3.75 and $2.65 per hour respectively, plus overtime, and they had to work harder and longer to finish the job in one day. Javier, however, said it was more money than they would make at home.

Juan was happy as long as he got to drive. Sunday night, Javier taught him to park the car in the narrow driveway next to their house without scraping the chain-link fence. While Javier took his shower, Juan backed the car in and out. He marveled that he could do it alone, and he would stop only when Javier called him to help with supper.

Tuesday after work, Juan was sitting behind the steering wheel when Javier came out to the parking lot. “Not tonight,” Javier said as he walked up to the driver’s side. “I’m in a hurry.”

Juan reluctantly moved over to the other side of the car. Javier got in and scooted the seat back. “You’re going out tonight,” Juan said.

“That’s right.” Javier started the car. “Do you want to come?”

“Where?”

“Come and see.”

They bathed, changed, and drove back downtown, where Javier parked the car in a lot next to a large, new building. The first floor was open courtyards and broad ramps. Juan followed Javier up one of the ramps, through glass doors, and into an air-conditioned lobby scattered with couches and chairs. Javier turned down the first corridor and kept going until Juan stopped to look through the small observation window of a wooden door. “Hey!” he hissed, seeing rows of desks. “This is a school.”

“That’s right,” Javier said, walking back for him. “It’s not bad. Come on.”

Juan pressed his back molars together as he’d seen Javier do to indicate distress, but he followed along.

Students were sitting in the classroom when they walked in. Javier spoke to a couple of people and took a seat toward the back of the group. Juan sat down across the aisle from him. A pretty young Mexican girl with frizzy brown hair said hello to Javier and gave Juan a look of appraisal. “Who’s your friend?” she said to Javier.

“My brother,” Javier answered.

She looked at Juan and grinned. “Going to learn English?” Juan scooted a notch lower in his desk and began to chew at a thumbnail. He jumped when the door at the back of the classroom slammed and a loud female voice rang through the room. The voice was incomprehensible, but everyone mumbled in response as the woman came walking up the aisle between Javier and Juan, her voice filling the room. A pale-yellow dress brushed against Juan’s desk as she passed, and he noticed black high heels, strong calves, and large hips. The woman set her books on the desk and turned, still talking and smiling. Her eyes were masked by large black-rimmed glasses that reflected the light.

The girl with the frizzy hair turned to smile surreptitiously at Juan, then looked back at the woman, who, hands clasped before her, was striding deliberately toward Juan. She stopped before his desk, her black high heels planted wide to support the body swaying gently from side to side. The voice rose in volume and pitch, then waited in silence. She spoke again, more emphatically. One of the hands clasped in front of the stomach released itself and made a rotund gesture that ended palm up before Juan’s face as if something might magically appear.

Juan forced himself to look up. No one had ever spoken English to him before; the only Anglos he had encountered were border patrolmen. The woman spoke again, pointing the hand at herself, then at Juan. The hand waited. Juan tried to smile, shook his hair back over his collar, tried to catch his breath. Again she spoke, and the hand rotated to the girl with frizzy hair. The girl responded, and Juan understood the last word—Elena. The hand floated to Javier, and Juan heard the name Frank. When the open palm floated back in front of his face, Juan took a breath and ventured, “Mario.”

“Repeat!” the woman said triumphantly. “My—name—is—Mario.”

Juan managed to get the sentence out and repeated it until the woman was satisfied. When she turned away, he felt battered and exhausted. Javier tried to encourage him, but he was too nervous to pay attention and simply waited in fear that she would come back. When the class was over, he bolted. Javier found him sitting in the car.

“You didn’t like it,” Javier said as he got in. Juan shook his head and looked out his window. “Well, you don’t have to go back.”

On the way home, Javier stopped the car at a fried-chicken franchise, went in, and came out with two boxes. They ate sitting in the car, watching through the plate-glass window as the young man in a red and white striped shirt waited on customers.

“That looks like good work,” Juan remarked. “It wouldn’t be so heavy.”

“Probably not,” Javier agreed.

“Put chicken in boxes, attend the customers, take the money.” Juan watched with interest. “I could do all of that.”

Javier dropped a bone into the box and wiped off his mouth with a napkin. “What would you say to the Anglos?”

Wednesday was payday. Javier stopped at a neighborhood grocery on the way home from work, had Juan endorse his check, and took both of their checks inside. When he came out, he gave Juan two ten-dollar bills.

“This is all?” Juan said as he fingered the bills.

“You made more”—Javier started the car—“but we have expenses.”

“Expenses?”

“Rent for two months. I got behind a month when I went to Jalisco. Two car payments—the same thing. And the store”—he tilted his head back toward the grocery—“they’ve been selling us food on credit. Then we have to buy gas for the car. And I had to borrow a hundred dollars to go home. It adds up.”

Thursday night, Juan decided not to go to class with Javier. They worked that weekend. Sunday night, on the way home, they stopped at a traffic signal four blocks from their house. When the light turned green, Javier stepped on the accelerator and a distinct ping came from beneath the car’s hood. The pinging became louder before Javier could get the car through the intersection and into the parking lot of a Seven-Eleven.

“What’s the matter with it?” Juan asked.

Javier shook his head in mute disgust, opened the car door, and walked around to raise the hood. Juan followed. They peered in at the engine, but neither could see anything out of place. Javier got back in, started the motor, and let it idle. As long as he didn’t step on the gas, it sounded all right. He got out and slammed the hood. “Let’s see if we can get it home.”

Within a block the pinging grew to a clatter as the car limped slowly to the house. Juan opened the gate and Javier parked the car in the driveway. “Tomorrow, maybe someone at work will know what this means,” Javier said after he got out.

The next morning, the alarm went off at four. Javier got up and stumbled into the bathroom. When he came out, he shook Juan awake. “What time is it?” Juan asked, squinting through eyelids that wouldn’t quite open.

“Four. It takes longer to go on the bus,” Javier answered.

It was still dark when they left the house to walk two blocks to the eastbound thoroughfare where buses passed. The air was muggy; moths battering themselves at a streetlamp were the only sign of life. They heard the bus’s whirr before they saw its square lighted windows. It pulled to the curb, and the door gasped open for them. Except for the driver, who took their money without speaking, the bus was empty and looked dirtier for the absence of people. Sitting on the plastic turquoise seats, they were aware of nothing beyond the insistent rocking and harshly lighted interior. The windows offered up their own reflections. Downtown, they got off to wait for a northbound bus. The sky had turned a royal blue that would pale with heat; an orange street-sweeper trundled past, brushing up the dirt and silence, putting down a snail’s wet streak.

When Juan and Javier arrived at the company, it was seven o’clock. They signed in and went out to the yard to help load materials. As the foreman gave instructions, he mentioned that they were starting a housing project in San Marcos, north of San Antonio. It would be an hour’s drive over and back each day. Juan went with Ascensión, as was his custom, and Javier rode with the foreman and his assistant. On the way over, Javier described his car’s symptoms. The foreman said it sounded like a thrown rod, or about $200 in garage bills.

That evening, it was seven o’clock before they got back to the company. In the bus on the way home, Juan asked about the car. “Two hundred,” he repeated after Javier and looked blank. “It’s a lot.”

“Two hundred more than we have.”

Juan thought about that a minute. “Then if we don’t have the money, it can’t be fixed.”

“Not without money,” Javier agreed. “It will have to wait till payday.”

They rode the rest of the way in silence. It was nine-thirty by the time they got to the house. They bathed, cooked supper, and ate. When they fell into bed, it was eleven o’clock. Five hours later, the alarm went off.

The week went by as a treadmill of fatigue. Each morning they got up at four; they never got to bed before eleven. At noon, they would eat as rapidly as possible to fall soundly asleep somewhere on a job site. They slept in the trucks on the way to work and on the way home. By Thursday, they were tired enough to sleep on the hard plastic seats the short distance in the bus going downtown. The distinction between sleeping and waking hours gradually crumbled as the week wore on.

Friday morning on the way to work Javier promised Juan they would take Sunday off. “One more day, and we sleep. Stay in bed till noon, get up to eat, then sleep the rest of the day. How does that sound?”

“What will you tell Joe?” Juan asked.

“That the car is broken. We don’t have a way to come to work.”

“It sounds good,” Juan answered.

The next morning, however, when Juan remarked thankfully that it was the last day before they slept, Javier didn’t answer. “We can sleep tomorrow?” Juan asked.

Javier looked away as if embarrassed. “Joe said he would pick us up at six-thirty.”

“You said we could sleep.”

“I told Joe about the car. He said he would come for us. We can sleep till five-thirty.”

Sunday morning, the pickup stopped for them and they got in back with another worker. When they pulled up before a large house, the worker looked at the shingled roof and the attached garage and said the Spanish equivalent of “That son of a bitch. We’ll never finish this.”

They worked hard all day, Joe pushing them as they were never pushed at the company. The hurry, the tension, and the thought of how late they were going to have to work created bad feelings, which made the day that much more difficult. At sunset, when they had half the garage left to shingle, Joe set up spotlights. They finished the roof at nine-thirty, but then they had to clean up, load the truck, and deliver the other workers. It was eleven-thirty when Juan and Javier got home.

Juan got no farther than the front room, where he dropped on the bed. Javier went into the bathroom, then to the kitchen, where he looked in the refrigerator. “You want eggs?” he called. When Juan didn’t answer, he walked into the front room carrying the skillet. “Eggs?” he said.

Juan stared at the pink ceiling, then shook his head.

“If you’re going to work, you have to eat.”

“I’m not going to work.” Juan looked at Javier.

Javier met his gaze, the electric fan tapping dully in the background, then turned back to the kitchen. He put the skillet on a burner, broke in six eggs, and lanced the yolks with a fork before stirring. On another burner, he dropped a flour tortilla over the blue gas flame until he could smell it beginning to burn, then plucked it up to turn it over. He divided the eggs between two plates, poured hot sauce over them, put tortillas on the side, and took them into the front room. He put Juan’s plate on the bed next to him, returned with forks, and sat down on a chair to eat. Without touching the eggs, Juan got up and went in the bathroom and took a shower. When he came back, he moved the plate of cold eggs to the kitchen table and lay down on the bed. “Tomorrow morning,” he said to Javier, “don’t try to make me go to work.” He rolled over on his side to face the wall.

The next morning Juan heard the alarm go off and Javier get up. Juan momentarily considered going to work, but closed his eyes and fell back to sleep. He woke again when the overhead light in the front room came on, thought there was still time to get up, but pulled the pillow over his face. He could hear Javier in the kitchen, then in the front room, and couldn’t really sleep until the lights went off and the front door closed. With equal shares of relief and guilt, he curled up in the middle of the bed.

A noise in the kitchen woke Juan to the heat filling the closed house. He lay in bed listening, thinking that it was hot enough to be noon, until he heard something moving slowly through the dirty dishes on the kitchen table. Stealthily, Juan rolled over to Javier’s side of the bed. He jumped up in the kitchen doorway to switch on the light, but caught only a glimpse of the rat as it slipped behind the refrigerator. Feeding roaches scattered on the table, stove, and around the sink. Juan opened the back door and then the front. Outside, he could see a wall of heat waves over the parking lot. He took his sky-blue pants from a nail in the wall and began to dress, putting on his pale-blue shirt and black boots. In the kitchen, he briefly considered the plate of eggs disintegrating in the heat before he decided to leave.

It was hot outside, but a relief from the stuffy house. Out of habit, Juan walked to the bus stop, then turned east and started in the direction of the tower. He could see only the revolving platform above the tall downtown buildings, but he decided he would find out what it was. As he walked, he began to feel conspicuous. There was no one else on the sidewalk, and he wondered if he was doing something he shouldn’t, if people could tell by looking that he was from Mexico. Javier had warned him not to go out till he knew how to behave, but Juan no longer cared about getting caught. It would be a free ride to Mexico.

Juan passed the fried-chicken franchise where he had eaten with Javier and, noticing that a Mexican girl was working at the window, decided to go back. He pushed open the glass doors, and beyond, through the inside glass partition, he could see the gold chicken basking on warming trays. The girl, her hair dyed an unnatural cherry red, her eyes raccoonlike with rings of white makeup, came to the window to take his order. “What do you want?” she asked in English.

Juan looked at the menu on the wall behind her. He could make out the numbers and the brand names of soft drinks. “Pollo, ” he said.

She switched to Spanish. “How many pieces?”

At a small table next to the window, Juan ate the chicken out of the hot, greasy box. He went back outside, taking what was left of his Pepsi, and continued in the direction of the tower. He crossed beneath the expressway overpass and walked along the edges of the small parking lots behind a series of restaurants and stores. In the next block, he noticed a sign in a restaurant window advertising in Spanish that help was wanted. He walked on, passed a cathedral, and crossed a small plaza. The tall buildings began to close in, making the car horns echo loudly and trapping the heat. Suddenly there were crowds of people on the sidewalk and the tower was out of sight. Reasoning that beyond the building he would find the tower again, he started into the chasm, then decided he should investigate the job in the restaurant first.

The man behind the cash register told Juan to talk to the manager in back and pointed a thumb over his shoulder, Crossing through the first dining room, Juan noticed a waiter setting tables and approved of the short white jacket and black bow tie he wore. Juan went through another dining room and on through swinging service doors. A Mexican woman folding red tablecloths directed him on toward the open door of a small office. When he tapped shyly on the doorframe, a woman wearing glasses looked up from the desk. “About the sign,” he said.

She looked at Juan until “the sign” registered, sized him up, and took off her glasses. Middle-aged, she appeared to be the sort of woman who went to the beauty shop once a week and thought a good deal about money. “You’ve got a Social Security number,” she said in Spanish. Juan nodded. “You come in every night at seven. Mop and wax the floors, clean. The dining rooms have to be spotless. Seven to seven, seven nights a week.” She raised her eyebrows.

“Can I tell you tomorrow?”

She lowered her head in consent. “If no one else has taken it.”

On the way out, Juan noticed the brown tile floors and saw that there were three dining rooms in all. The restaurant hadn’t seemed so large until he looked at all the tables and chairs and imagined moving them to mop. Walking home, he considered the advantages of the restaurant. The work wouldn’t be so heavy or hot as at the company, and it was close enough to walk. He would stay long enough to buy gifts to take home.

The house was hotter still when Juan got back. He opened the doors, took off his shirt, and turned on the fan. It was too hot to lie down on the bed, so he washed the dirty dishes and stacked them on the counter to dry. When he finished, he sat on the back step till he noticed a patch of shade beneath a dusty chinaberry tree that he judged was just right for a nap. He got a blanket, latched the front screen door, and went out back to make himself comfortable in the shade.

When Juan woke, it was late afternoon, the time when he and Javier would be getting back from the company. The thought of Javier made Juan nervous. He got up, went in the kitchen, and poured himself a glass of punch. Realizing he was hungry, he decided to go ahead and make the tortillas. He ate two with margarine, then swept the floor, made the bed, and straightened the front room. He was sitting in the dark on the front step, listening to the thud of the jukebox, when he saw Javier come walking in across the parking lot. From the way Javier walked and opened the gate, Juan could see how tired he was. Neither of them spoke. Juan stood up to let Javier pass, then followed him into the house.

Javier sat on the end of the bed, dropping his lunch box on the floor. He was leaning forward, his forearms resting on his spread knees, his hands like stiff leather work gloves dangling before him. His head hung down as if he were studying the floor between his feet.

“I got a job,” Juan said.

Javier cocked his head with interest but did not look up.

“At a restaurant downtown,” Juan went on. “I saw the sign in the window and they said I could have the job mopping and waxing the floors. I go to work at night. Seven nights a week.”

“How much do they pay?” Javier asked.

“Oh.” Juan realized he hadn’t asked. “They didn’t say.”

“And overtime. Do they pay overtime?”

“I don’t know.”

Javier looked up at Juan. His face was exhausted. “You and me,” he said, “what we have is work. If we couldn’t work, no one would want us.” He looked down at his hands and was silent a moment. “Work is all we have and the only way we can lift ourselves. But you have to pay attention. It’s like a lesson, work. If you don’t pay attention, you don’t learn or move ahead.”

He looked up at Juan again and saw he didn’t understand, then looked again at his hands. “When I came here, I was like you. I didn’t know anything. The first day, I was walking down the street and saw some men making a sidewalk. I asked them if there was work and they sent me to the boss. He looked at me and said, ‘Do you know how to work?’ I was scared. I had never worked here, didn’t know if I could do what he wanted, but said, ‘Yes, I know how to work.’ I had to.

“So I worked hard that day. Shoveled dirt. The other men told me not to work so hard, but I didn’t mind. I was afraid he wouldn’t pay me. At the end of the day, the boss gave me eight dollars. Enough for my room and something to eat. The next day, I learned how to mix cement. I kept working hard and at the end of the third day he gave me ten dollars. And told me not to tell the other men. It made me happy till I heard one of the men say he was getting a dollar-seventy-five an hour. Then I knew that the boss was cheating me. I thought I might quit, but I couldn’t, and I was beginning to see how the work was done here, so I kept watching, then went to the boss. When I asked for more money, he said, ‘Javier, do you have the Social Security card?’ I said, ‘No.’ I didn’t know what that was. He said I couldn’t work without one, but if I would stay, he would get me one. So I stayed. When the card came, he showed it to me, but he said he would keep it so I wouldn’t lose it. He kept it because he didn’t want me to leave. But he started to pay me like the others, so I didn’t complain.

“At the end of the month, I knew how sidewalks were made. The man who brought the sand in the dump truck had been watching me. He said I was a good worker and asked if I wanted to come with him. I said no, that I was learning about sidewalks, and the boss had my card. He told me the boss had no right to keep my card, that I had rights. He said he would get my card for me and would teach me how to drive the truck. So I got my card and learned how to drive, and he helped me get my driver’s license. But the important thing I learned was that if I worked hard, I would have some rights and a better chance would come along.”

Javier sat up on the bed and looked at Juan. “Since then, I’ve always learned something at work, and each job I’ve had has been a better job.”

He stopped a minute as if he had run down, then asked Juan, “You know why I’m working for Joe on Sundays?” Juan shook his head. “Not because he pays good but because I want to see what he’s doing. If he can work alone, then so can we. The hard part is getting the jobs and learning how to bid. The rest we can do. I’ve started buying tools. As soon as we get the car fixed and paid for, I’m going to trade it in on a pickup. Then we can look for our own jobs.”

Juan looked skeptical. “You don’t have papers,” he objected. “Joe is legal.”

Javier narrowed his eyes as if shading them from the truth of what Juan said. “It doesn’t matter. People say I’m crazy, but I don’t care. They told me I couldn’t come here to work, but I came. They always told me what I couldn’t do and it never stopped me. Five times they caught me and sent me back, and five times I’ve returned. Once they know me in one place on the river, I can go to another place to cross. They can’t keep me out.”

Juan shrugged nervously and shook his hair back over his collar. Javier caught himself, exhaled a deep sigh, and continued in a calm tone of voice. “Someone from the garage is going to come tomorrow for the car. Wednesday, we get paid. We can drive to work on Thursday, and you can drive again.” He looked at Juan.

“At the company, they’ll take me back?” Juan asked.

“I told them you were sick.”

Juan thought for a moment, then shrugged.

As Javier promised, the car was repaired, they were able to drive to work, and Juan continued his lessons. Each morning they slept till five, and at night they were in bed by ten. On Saturday, they worked for the company; on Sunday, they worked for Joe. Slowly they began to catch up on sleep, and once they were freed from the bus schedule, their lives began to return to normal.

The following week, the crew got an assignment in San Antonio. It meant less time on the road, more time at home. Tuesday night, Juan and Ascensión left the job site a few minutes before the others. When they got back to the company, Juan went out to the parking lot to wait in the car. Since Javier was returning to English class that night, Juan didn’t expect a driving lesson and got in on the passenger’s side. He sat watching the other men coming out, trying to guess which car each would go to and daydreaming about what kind of car he would like to have. The parking lot emptied, shadows grew long, the flow of men dwindled and finally stopped.

Juan turned in his seat a couple of times to look toward headquarters. Javier, he imagined, was inside talking with some of the others. It was getting so late that he wondered if Javier had decided not to go to class. Perhaps he would get to drive after all, Juan was thinking, when the foreman with the fierce-looking moustache and sideburns stuck his face through the driver’s window. “Hey, Mario,” he said. “Immigration stopped us on the way home and got Frank. Frank asked me to give you these.” He held out the car keys for Juan.

From The Long Road North, to be published this month by Doubleday & Company. ©1978 by John Davidson. Two chapters have previously appeared in this magazine: “The Long Road North,” October 1977, and “The Chase,” December 1978.