This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

It comes back to him in strange ways, at unexpected times. One day recently, Dean Nichols was driving down the street in Dallas, feeling very much like a normal person for the first time in years. Then he spotted the squad car in his rearview mirror.

Momentarily, he reacted as any normal person would: his adrenaline rose and his heartbeat accelerated. He ran through the litany of authorizations, stickers, and numbers that are the bane of any driver’s existence—he’d forgotten to renew the plates. Should he pull over? Take the next right? Slow to a crawl and hope the squad car passed him? Speed up and try to lose it?

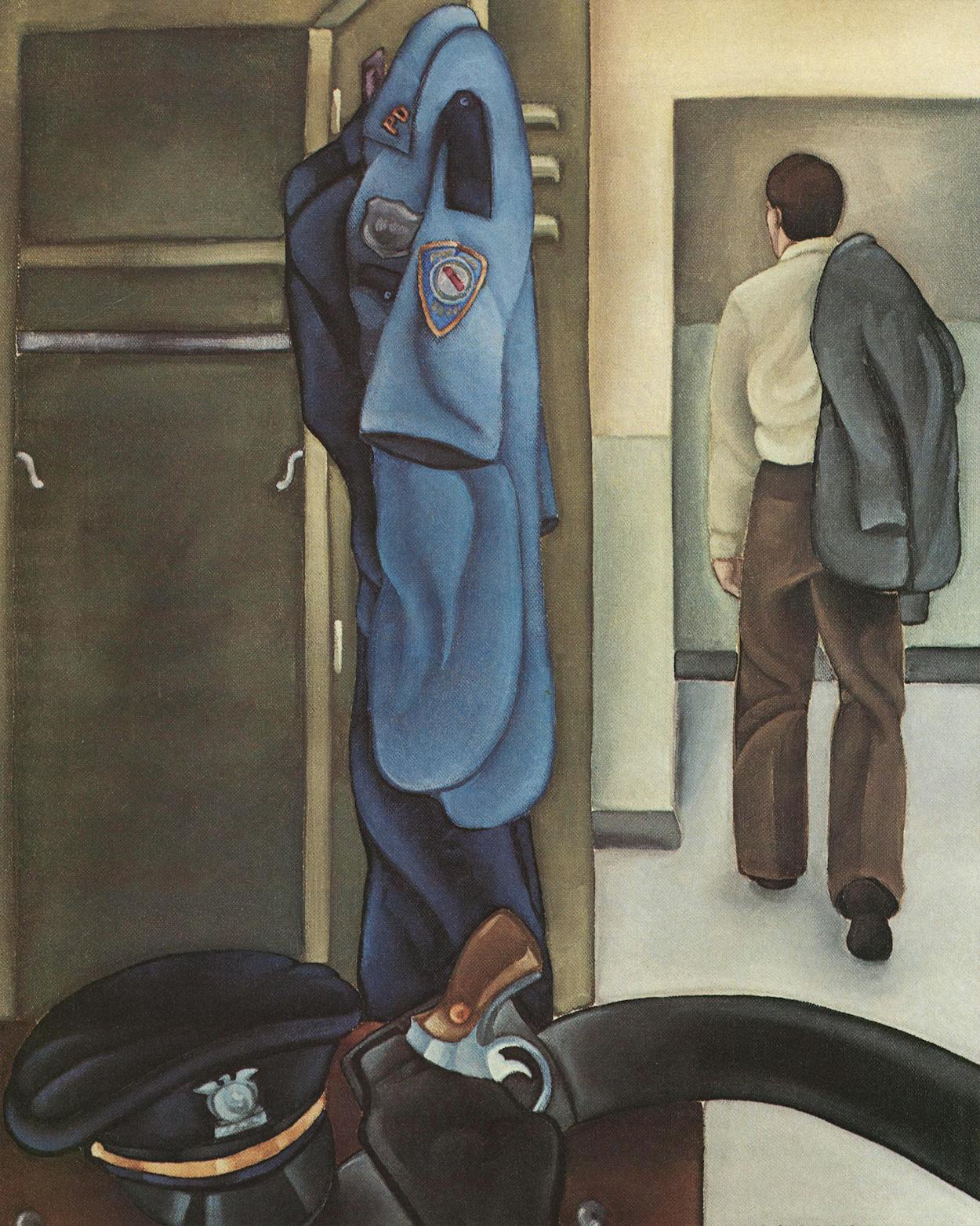

Dean suddenly found himself grinning. Pull over? Slow down? Speed up? What was he thinking? Those were the very actions guaranteed to arouse suspicion in even the most inexperienced cop. He knew. Only a few months before, he’d been that guy in the squad car, roaming the streets of Houston, looking for some poor fool ignorant enough to slow down at the sight of a cop in his rearview mirror.

He was grateful for the chance to smile, because he was not usually amused by reminders of the five years he had spent as a cop. Most of his memories were unpleasant: bodies strewn across the Gulf Freeway; the stern eyes of a superior advising him he’d just received a complaint from some citizen Dean had thought he was helping; the putridness of the drunks on deep Main; the pungent smell of burnt gunpowder; the relentless crackle of the two-way radio.

Why had he quit? The cause was all of those things, but it was also something more, more than fashionable theories like “stress overload” and “burnout.” He had been worn down by the Ragged Edge—a curious mélange of false assumptions, misguided good intentions, moral paradoxes, ethical ambiguities, impossible demands, and outright lies that has shaped our expectations of police officers. Cops are hired to fight crime, catch crooks, make our streets safe. But all too often they are told to do their jobs in such a way as to guarantee failure. Fight crime, yes, but do so politely, cautiously, without stepping on toes. Make our streets safe, to be sure, but also be there when we need consoling after our homes are burglarized, when we have spats with our spouses, when the neighbor’s dog is digging up our flower beds. Risk your life, of course, but be careful when you decide to shoot back. And accept the designation as one of Houston’s or Dallas’ or San Antonio’s finest, but don’t expect us to respect you.

The first time he confronted the Ragged Edge, Dean had been a cop for three weeks. He and his partner were tooling around the Fifth Ward on patrol when they got a radio call: “Disturbance in a bar.” Routine, they thought. “Man with a shotgun,” hissed the radio. Not routine. The cops ripped through intersections, squealed around corners, and pulled up in front of a dingy little dive with a single door and no front window. They jumped out of the car and shoved open the door of the place. The light inside was dim and purplish; the air was murky and dense. They could see only fragments of figures, but a single image at the center held their gazes riveted. It was a pump-action shotgun, poised like a rattlesnake, in the hands of a lurching middle-aged man.

“Police!” yelled Dean’s partner, as they drew their guns. “Drop the gun. You drop it right now!” The man gave him a rheumy-eyed stare. The cop shouted the order again, then a third and a fourth time. The gun didn’t move. Dean joined in the shouting, and for a few moments the whole scene was absurdly comic.

Dean could feel the trigger of his .357 Magnum against his right index finger, only the slightest pressure away from propelling a fatal bullet right between those rheumy eyes. That’s where he’d had it aimed all along, not at a knee or a hand or the gut but right between the eyes. Merely wounding a man holding a gun could only make him more desperate and more deadly.

Inexplicably, the slender man began to move forward; as he did, he lowered the shotgun. Dean didn’t hesitate. He took two quick steps and kicked the gun savagely. As his partner retrieved the skittering weapon, Dean grabbed the drunk by the shoulders, whirled him around, and shoved him up against the bar. “Keep your hands up there!” he shouted. “I don’t want to see them move.”

As Dean furiously frisked the suspect, he could hear his partner methodically purging the pump-action of its ammunition; with each shell that thwacked to the floor, he could feel the rage building inside him. He began to understand what had happened during the past ten minutes. That gun really had been loaded; that drunk really could have killed them. Thinking about it didn’t scare Dean Nichols. It made him mad.

Dean was almost through with the frisking when his partner walked over and casually tossed the shotgun onto the bar, accidentally bumping the suspect’s hands. From his position behind the man, Dean couldn’t see what had happened, so when the suspect let out a blood-curdling yelp and whirled around, Dean didn’t think. He punched the man in the jaw. The impact of bone on bone stunned Dean almost as much as it did his victim. As he watched the man trying to shake out the cobwebs caused by the blow, he screamed, “You jerk! You almost made me kill you!”

Dean Nichols knew that instants like that were ultimately why he’d quit. It wasn’t really the midnight dinners, the bad pay, the strained relations with his wife and friends. It wasn’t really the constant physical threat. It was the relentless friction between his expectations of police work and the cruel realities he found on the streets—the Ragged Edge.

Dean tried to crowd all these memories out of his mind as he noticed the squad car passing him. He had a new life now. He had three children to get reacquainted with, a wife to repay for five years of patience. He had studies to pursue that would prepare him for the ministry. And he had a job opportunity to check out, a job as a salesman in a gun store. It wasn’t exactly what he’d had in mind, even for interim work, but then, those five years as a cop hadn’t been exactly what he’d had in mind either.

Losing Ranks

Dean Nichols is not the only good cop who has quit a major city police force in recent years; attrition in police ranks has become as big a problem as the crime rate. The Houston department was once one of the fastest-growing forces in the nation. Between 1970 and 1976, it gained 940 officers, an increase necessitated by the city’s growth. But between 1977 and 1981, it gained only 359 officers, giving it a paltry 5 officers per square mile. (Los Angeles, for example, covers roughly 100 fewer square miles but has twice as many policemen.) While recruitment is up in Houston right now, thanks to growing unemployment, the city’s population explosion has created a troubling reality: the police are forced to do less and less about more and more.

The Dallas Police Department, which has enjoyed a spotless image since the chaos of the Kennedy assassination subsided, may have even worse problems. After losing nearly 200 of its officers last year, the department now finds itself below its 1975 force level. And the San Antonio force is 100 officers below its desired level. Elsewhere in the nation, in San Diego and Baltimore and New York, the attrition rate is a consistent 10 per cent. The New York City Police Department now employs 22,700 policemen; in 1970 the city had 31,000 officers.

Throwing more cops at crime will not make much difference in the crime rate—on that almost everyone agrees. But no one has ever bothered to figure out how many cops are too few. In Texas we may find out the hard way. Already, Dallas and Houston are the worst off of the nation’s eight largest cities in terms of officers per square mile and per capita. Since 1977, crimes reported in Dallas and Houston have increased by more than 20 per cent; at the same time, clearances (arrests) have remained steady or even dropped—meaning that more crimes are occurring but fewer are being solved. While most major cities experienced declines in crime during the first six months of 1982, Texas’ major metropolitan areas suffered increases. And finally, one other statistic—the one the public, perhaps wrongly, seems to care most about—response time, which is a measurement of the speed (or lack thereof) with which police officers respond to radio calls. Earlier this year, Houston’s new police chief, Lee Brown, admitted that his department’s average response time to a call from the public was more than thirty minutes. “That is simply unacceptable,” said Brown. True. But Houston, like most cities, assigns priorities to calls—emergencies are answered faster than routine calls. What the thirty-minute overall time does show is how seriously understaffed the Houston street patrols are.

“Dean began to learn more disillusioning things. Some officers regularly drank while on duty; others had such a cavalier attitude that they routinely took their own sweet time responding to calls. But he was stunned by the overt racism.”

Over the past five years, few police departments have had a reputation worse than Houston’s. The widely publicized slaying of Mexican American Joe Campos Torres by three Houston police officers in 1977, along with other killings, gave the department a name as a killer force, staffed with unthinking rednecks and lethargic managers. But Dean Nichols didn’t quit when the force’s image problems were at their zenith; like a lot of Houston cops, he worked through that. He resigned at a time when the department had largely straightened itself out and was anticipating the selection of a new chief of police.

Dean Nichols is precisely the sort of young man any reasonable citizen would want to be a cop. He is college-educated, bright, mature; he wasn’t afraid to use his nightstick if necessary, but he never considered his uniform a license to brutalize suspects. He made his share of arrests, took his share of abuse, worked his twelve- to sixteen-hour days without complaint. Throughout his five-year career, he remained a patrolman, eschewing promotion to a desk job. Most of the time, he truly believed he was performing a public service. He was the cliché: a good cop, nothing more and nothing less. In the end, the question for Dean Nichols—and hundreds of others just like him—was simply this: why would anyone want to be a cop anymore?

Big Night at the Hole

Dean Nichols was reared in Beaumont, the eldest of four children. His father was a disabled war veteran, and his mother was a waitress. They died within eighteen months of each other, when Dean was nine. He and his brothers and sister moved to Kerrville to live with their grandparents, and his strict Baptist upbringing there formed the basis for his later ambition to become a preacher. Dean was an unremarkable youth: square-jawed and farm-boy handsome, blockily built and swarthy, with an infectious, nasal laugh. He was a tough, competitive athlete, known more for desire than for natural talent, and an industrious student, known more for his hard work than for his gifted intellect.

“Dean liked to think he was a warrior against crime, but he understood that he was also a public servant, a clerk who processed human depravity and misery. He was confused about which was more important: being a warrior or being a servant.”

He graduated from high school in 1969 and studied criminal justice at Sam Houston State University. After only a year, he tired of academia and joined the Air Force. He served a year in Viet Nam, then returned to the U.S., to Bergstrom Air Force Base in Austin, where he worked as an air traffic radar technician.

In Austin, he became friends with an older policeman who worked for a small city nearby. During frequent rides on patrol with his friend, Dean was fascinated by the multitude of problems the average patrolman faced each day. He also enjoyed the contact with people, and he soon decided to become a street cop.

In late 1976, having finished his hitch in the Air Force and earned his degree at Sam Houston State, he was accepted by the Houston police force. He took the job, but Houston was an odd choice. Already the department’s problems had begun to leak out to the newspapers; one of his professors sternly warned him against Houston and urged him to join the Department of Public Safety or the FBI instead. But Dean was firm in his resolve to be a street cop, and as long as he was going to be working the streets, they might as well be the toughest streets in Texas.

The police academy Dean attended in Houston was in his view a necessary evil. Some of the exercises he had to go through didn’t make much sense to him. There were mock arrests, mock struggles, mock tickets to write. The recruits were awakened at six and sent off to classes in proper nightstick use, investigative report writing, handling of life-threatening situations. After a quick lunch they had more course work, in communicative skills and coping with multicultural stress, then hours of rigorous physical training, pistol range practice, and high-speed driving instruction. Like all police academies, Houston’s emphasizes not so much the day-to-day police work as the rare but potentially deadly episodes: the shoot-out, the high-speed chase, the hand-to-hand combat. Dean couldn’t wait until his four months of training were over and all those exercises became real.

At the same time, he got another kind of indoctrination. A police department can best be compared to a fraternity, and the four months spent at the police academy to pledgeship. Recruits are there to be initiated. “Protect your partner at all costs,” they are taught. At every turn the recruits are reminded that their calling makes them special, sets them apart.

Dean Nichols had no objection to such an ethic, at least in theory. Camaraderie with one’s colleagues was vital to police work. There was one aspect of the Fraternity of Blue business that did bother him, though. Many of his classmates were experienced cops from Northeastern cities who had come to Houston after being laid off. These men were older and wiser, to be sure, but they also seemed coarse and cynical. They seemed not merely clannish but downright snobbish, resentful of the civilian community. Dean recalled one particular conversation that both confused and dismayed him. A few of the recruits were sitting around one day after lunch, listening as one of the older fellows held forth on the time-honored police buddy system.

“A partner,” he said, “should back up his buddy no matter what.”

“Well, sure,” Dean said. “As long as his intentions are right, yes. If he screws up, no.”

The older officer fixed a steely gaze on him and said, “Well, then, you’re going to have trouble when you get out there.”

In his first month on the force, Dean learned as much about police work as he had in four months at the academy. He and his partner quickly became friends and discovered that they had in common a basic attitude toward police work. Policing wasn’t just tough-guying it; a lot of times, it required the opposite strategy, an ability to assess a situation, assign a priority to it, and act swiftly and firmly. And it required patience. Dean still liked to think he was a warrior against crime, but he was too smart not to understand that he was also a public servant, a kind of clerk who processed human depravity and misery. He was also smart enough to be confused about which was more important: being a warrior or being a servant.

After one month Dean had his first review and joined a new partner. His original partner gave him a glowing score. “Officer Nichols,” a lieutenant told him, “you seem to be one of the best officers who’s come through here in a while. Keep it up.” Then Dean met his new partner. They didn’t like each other, and they also disagreed radically on the nature of their work.

At the same time, Dean began to learn other disillusioning things. Some officers regularly drank while on duty; others had such a cavalier attitude that they routinely took their own sweet time responding to radio calls. Dean once heard a patrolman say to a man he had stopped, “You goddam nigger! Don’t you ever run a red light in my sector!” Dean understood the frustration with people who ran red lights; truly they were dangerous. But he was stunned by the overt racism.

Dean also found out that some cops spent a good part of their shifts at a little-known institution called the Hole, a place that they had rented for rest and relaxation. The Hole was a tiny white frame shanty near the North Main overpass of I-45, a stone’s throw from police headquarters. It was furnished spartanly with a desk, a police radio, a typewriter, a couple of chairs, and a cot. Some officers wrote reports there; others went there to get away from the office and their squad cars. And some used it as a place to party and swap war stories. In its way, the Hole was symbolic of one of the least-understood frustrations of police work: you never, never can get away from it all. Ordinary citizens can take an extra fifteen minutes at coffee break, slip out in the afternoon for a walk, leave work early and have a couple of drinks. But a cop is a marked man. His uniform and badge make such simple pleasures impossible. Hence the shabby confines of the Hole were regarded as something of a sanctuary.

During stops at the Hole, Dean usually stayed in the car and read while his partner visited with his buddies inside. One Friday night—March 11, 1977, to be exact—Dean and his partner had stopped off there, when suddenly the radio invaded the silence: a young black man had run a red light on Main and refused to pull over, choosing instead to give the pursuing patrol car a high-speed tour of the downtown-Montrose area. Instantly Dean’s partner and several other officers emerged from the house and jumped into their cars.

As they careened through the streets of Montrose and finally picked up the chase, Dean could see that matters were getting out of hand. A chase like this was something no cop could resist. Within minutes, a dozen cars had joined in screeching pursuit of the suspect; before it was over, there would be fifteen units in the caravan, including a helicopter. The suspect didn’t seem to be intimidated by the phalanx of lights behind him; instead, he drove faster and faster. The chase lasted five, ten, fifteen minutes until finally the young man pulled up at the same place where such fugitives usually do: in front of his own house.

When Dean and his partner arrived, they could see that half a dozen officers already had the suspect on the ground, but he was struggling vigorously. As Dean later described the scene in his report to his superiors, “I (Nichols) got out of the car and ran towards . . . officers who had the actor [suspect] down on the ground, laying face down. I grabbed the actor’s legs and put them in a brace . . . the actor’s left hand had been cuffed. By applying pressure to the leg brace, the right hand . . . came around to his back. I then personally cuffed the right hand.

“At this time, the actor was secure and was no longer fighting with officers. . . . I noticed about 3 officers kicking the actor in the head and ribs. One police officer was grabbing the actor’s hair and beating his head on the ground with a great deal of force. One police officer placed his foot on the actor’s head and stood on it. All this happened while the actor was laying face down, handcuffed, and I still had him in a leg brace.”

What Dean did next was, as far as his shocked fellow cops were concerned, a betrayal of their code of brotherhood. He told them to stop, that they were brutalizing their suspect. They told him to “shut up and let the police officers do their work.”

Back in the car, Dean’s partner told him that the other officers were extremely upset with him and that he’d “better keep his mouth shut.”

Dean said, “I’m not going to shut up. What I did was right. I’m tired of all your crap.”

The words were barely out of his mouth when his partner reached over and popped him in the chest with the heel of his palm. Dean didn’t think; he reacted. He struck his partner back, and for one insane moment, two of Houston’s finest scuffled like school kids in the front seat of the squad car. Their sergeant finally ran over to the car and broke them up, ordering them to return to the station. “You might as well consider yourself fired,” the sergeant said to Dean.

At the station, Dean began writing his report of the incident. As the rage continued to well up in him, the report grew longer, more passionate and vitriolic. He was not merely describing what he believed to be a violation of the departmental code; he was purging a month’s worth of frustration created by the conflict between him and his fellow officers.

“I have seen several things during the past 4 or 5 weeks that have made me wonder about my career as a Houston police officer,” he wrote. “Just too many things have happened that I thought or know were wrong.” Then Dean detailed the most unsavory rituals of the Fraternity of Blue. “Drinking on duty,” he wrote. “Staying in a house, listening to a police radio, so as not to be driving around. Falsifying offense reports in order to justify an arrest. . . . Waiting on calls given by the dispatcher in order to finish personal business. Intimidating a man because of his race.

“I do not believe these things are right, nor do I believe the citizens of Houston will believe these things are right,” he concluded.

But first, as he knew all too well, he had to worry about whether his immediate superiors thought they were right. Soon after turning in the report, Dean could see that the other officers had a copy of it and were busy constructing their responses in another office. He walked out into the lobby area and noticed a young man with a notebook sitting there. He suddenly saw where his survival lay. “Are you a reporter?” he asked. The man nodded. “Well, I think maybe I need to talk to you. I think I might be in some trouble here.”

At two o’clock the next morning, when his wife met him in front of the station, he said, “Honey, buckle your seat belt. We’re going to be in for a rough ride.”

That turned out to be an understatement. By the simple act of writing that report and standing by it, Dean Nichols had flouted the unwritten covenant stating that fraternity brothers stick together. When he read the headline POLICE VS. POLICE ON BEATING CLAIMS in the Sunday Houston Chronicle, Dean Nichols realized that he was in for the fight of his life.

When he went to work on Monday, he was placed in a menial desk job while his fate was being decided. The constant headlines over the next two weeks made him an unwilling celebrity. To some citizens, especially the victim, Demas Benoit, he was a hero and a martyr, one courageous voice who was finally exposing the awful truth. To many of his peers he was little more than a snitch. At first Dean considered quitting, but he rejected that idea as cowardly. Soon he picked up a rumor that he was going to be fired. An internal investigation was under way, and the other officers not only provided justification for their actions but also accused Dean of “leaving his post” when he had returned to his car that night. In the policeman’s world, there is hardly a more serious allegation. His sergeant pressured him to write a second report, leaving out many of his ancillary allegations. Under the strain, Dean relented.

Harassment had begun almost immediately. His wife received threatening phone calls at home. “We know where you work,” the voice said, “and we’re going to get you.” The calls lasted six months, until Dean finally told a sergeant, “Look, I know who’s doing this, and you get it back to Central that I’m going to put a tap on that phone.” The anonymous calls stopped.

But the disgust of his peers never abated. Dean’s newspaper strategy eventually saved him his job, since Mayor Fred Hofheinz found it politic to intervene in the rookie’s behalf. The internal investigation found that no brutality had occurred, but the chief announced that Dean would remain on the force. He went back to patrol, but many officers still disapproved of what he had done. “You know, maybe you made a mistake,” a captain told him one day. “Maybe you just didn’t see what you thought you saw out there.”

“That’s a lie, Captain,” Dean said. “You know as well as I do what went on out there that night. And it’s going to take someone getting killed before you do something about it.” Less than two months later, three Houston policemen were accused of murdering Joe Campos Torres.

You’d Quit Too

One of the best-kept secrets in the history of law enforcement is that the public doesn’t really want a powerful police force. Since the start of policing, in London in 1829, public sanction of police has been sporadic at best. Opposition to police patrols in London was fierce and uncompromising. Traffic cops were routinely ridden down and lashed with whips; the killing of a policeman who was trying to suppress a riot was ruled justifiable homicide by a court. Thus began the Ragged Edge: cops are supposed to fight crime, but they’re supposed to do it without stepping on toes. The premise has been impossible from the beginning, and so it’s no wonder that young officers begin to feel that the public is not really their constituency but their enemy.

In time, technology further conspired to estrange police officers from the citizenry. Following World War II, police patrol moved almost entirely off the neighborhood sidewalks and into squad cars. The object was to increase police presence and to speed response to citizens’ calls; the effect, however, was to separate the police and the public. Gone were the days of foot patrol, when the cop knew a neighborhood, the opening and closing times of its businesses, its alcoholics, its troubled kids—its vulnerable spots. With the advent of the car, the only contact a citizen had with the police was negative.

The tragedy of the cop’s isolation from the public was that it didn’t pay off. In the mid-sixties Yale sociologist Albert Reiss evaluated the effect of vehicular patrol by reviewing patrol response patterns in three large cities over a five-year period. His findings stunned law enforcement: the average patrol car, Reiss concluded, was involved in non-crime-related activity 99 per cent of the time. Further studies in New York and Kansas City revealed that even doubling or tripling the number of patrol cars in a particular area had no impact on the crime rate.

Despite the evidence, most police departments still devote a majority of their manpower and resources to vehicular patrol. The reason is politics. Citizens have come to expect that whenever the spirit moves them, they can dial a magic number and a patrol car will appear instantly. Reiss found that more than 90 per cent of the incidents a patrolman became involved in were initiated by citizens. Hence the public, not the police, began to define crime-fighting priorities.

The advent of the two-way radio widened the breach between cops and the public by forcing policemen to respond to calls miles away from their regular beats. Response time became an important indicator of productivity. Crime might have been up 10 or 20 per cent, but police chiefs were satisfied to announce to the public that the average response time during the past year was under five minutes. These warped priorities were made all the worse by the credo that cops must enforce all the laws and enforce them equally. They must respond to burglaries in progress as quickly as to armed robberies, to domestic arguments as quickly as to murders. It became routine for the police to deal with strangers in high-stress situations in a hurry so they could go on to the next call.

The policeman’s estrangement from the rest of society has tangible results. William Kroes, an expert on police stress, discovered that police work led all other occupations—by far—in deaths connected to stress-related illness; he also found that roughly twice as many policemen commit suicide as die from assaults. A study by the International Union of Police Associations (IUPA) revealed similarly disturbing data: the divorce rate for policemen is twice that of other citizens; the incidence of chronic alcoholism and gastrointestinal disease is much higher than the norm; a police officer’s health tends to deteriorate ten years sooner than that of the ordinary citizen. Perhaps the most stunning revelation in the study is that, contrary to current thinking, the chief stress on a cop is not the prospect of death but the ever-present concern that he will make a mistake or not be backed by his department. As Dean Nichols says, “Cops don’t worry about dying. They worry about being dishonored.”

Suspicious of the public and of his own superiors, the policeman builds an overdependence on his buddies. In the process, he creates his own little world, with—as Dean Nichols found out the hard way—its own rules. Depending upon his degree of insulation from the real world, the cop can become merely unproductive or, at worst, as dangerous as the criminals he’s supposed to be protecting us from.

Hunting Ducks

A good deal of Dean’s work was dreadfully boring. His police shift started at three in the afternoon, but his day began at five-thirty in the morning, when he left for his other job. Second jobs were a fact of life for a policeman. With a wife, a mortgage, and a growing family, a patrolman’s $20,000 salary wasn’t enough. Off-time security work was easy to find, and so Dean had begun working mornings as a guard at Hermann Hospital. It added another $10,000 or so a year to his income, but by three o’clock he was often tired, frazzled, and distracted.

His shift would begin with leftover calls from the day shift. These were generally investigations of burglaries that the previous shift hadn’t been able to sandwich in between emergencies. Dean found them an annoying waste of time. He was little more than a clerk for a burglary victim and his insurance company.

After running his burglary calls, Dean would usually find a busy intersection and “hunt some ducks”—police talk for writing traffic tickets. There was no rigid quota, but every Houston cop knew he was expected to bring in at least two ducks a day. It was another way for the department to convince itself that it really was doing something about crime. Shooting ducks was simple. If Dean waited long enough, someone would run that red light; if not, he could always spot a motorist with “bad paper”—an expired license or an out-of-date inspection sticker. Once Dean bet a friend who was riding with him for the evening that he could pick out six motorists in a row who were driving without their licenses, just by studying their faces. His friend paid for dinner.

The rare opportunity to make an arrest is what a policeman lives for, but in modern police work that procedure too has become just another wearying aspect of the job. A simple firearms possession arrest could take the remainder of an officer’s shift. To get the lawbreaker behind bars, the police officer first had to make arrangements to transport the suspect’s car to a police storage lot. Departmental policy recommended that the cop himself drive the suspect’s car there, but Dean always preferred to call for a wrecker. He didn’t like driving suspect’s cars; it presented too many opportunities for the suspect to get back at the officer by claiming that the officer had taken something from the car or had damaged it. Then Dean had to get the suspect to the station and check him through the homicide department. Did he have any assault or murder warrants? How about the gun? Had it been involved in any such incidents? Finally, Dean had to write his report, a slow and painstaking process, since any mistake might render it invalid in the courts. After he turned in the report, the suspect was booked into jail, and then Dean had to go over to the district attorney’s office and go through the whole process again. The circumstances and charges were repeated to an assistant district attorney, who then had Dean formally swear to all the facts. More copies in triplicate had to be typed up and signed before Dean could finally return to the streets. The process could be completed in only an hour or two, but if anything intervened—a traffic jam, complications at homicide, a backlog at the DA’s office—it might take five or six hours.

Dean and some of his colleagues would often set up roadblocks and check licenses, just to see if they could flush out a “rollin’ stolen” (hot car), an illegal firearm, an old burglary warrant, or a car with three TV sets in the back seat. This procedure invariably worked well. Sooner or later, one of the cars in line would back up and make a U-turn, and that car usually turned out to be hot.

Whatever patrol time wasn’t eaten up by old burglary calls, traffic work, and the occasional arrest was consumed by domestic disturbances. Out of the eight or ten radio calls Dean got every day, at least half involved a husband-wife or boyfriend-girlfriend spat and were generally fueled by liquor, jealousy, or a hot afternoon. Dean’s routine in such situations was simple. He’d first listen to a rough outline of the dispute from each participant. Then he’d try to figure out how dangerous the situation might be. Could he see a weapon in the home? How drunk were the antagonists? Was there any history of disputes in that home that would suggest that the people liked to quarrel and nothing more? If he sensed danger, he’d begin by checking warrants on both parties. The key in any heated domestic dispute was to get the warring parties separated quickly, and the easiest way to do that was to dig up an old warrant on one or the other and haul him or her down to the station to sober up. Otherwise he’d try to persuade the more belligerent party to stay with a friend or relative. If the person refused, the officer had no choice but to leave. Dean often felt that if he could have more time in such situations, he might be able to cool the quarreling couple off. But a Houston patrolman has no such luxury; he is at the mercy of that radio, which can summon him at any time. In most cases, the best the officer can do is to issue a stern warning.

There was another reason for police officers to leave well enough alone. More than one cop had left a domestic dispute satisfied that he had solved the problem, only to be summoned to the sergeant’s office when he returned to the station. Someone—sometimes the same person who had called for help—had complained to his superior about harassment, abusive language, or a “bad attitude.” Sergeants and lieutenants generally take such complaints seriously; since the sixties, when police brutality became a matter of public concern, departments have spent as much time worrying about their images as they have spent fighting crime. Internal affairs departments have grown by leaps and bounds, and millions of dollars have been spent on community relations departments. Any serious complaint from a citizen is investigated.

The Flamingo Road Disturbance

It was a domestic disturbance that pushed Dean Nichols onto the downslope of his career as a police officer. One evening during his second year on patrol, Dean received a call to check out a disturbance on Flamingo Road in southeastern Houston. The address sounded familiar, and Dean realized that the couple was a “regular” on his beat. About every six weeks there’d be a disturbance call from the house, usually because of another drunken argument about money. Those calls always perplexed Dean because the couple was middle-aged and lived in a modest but well-kept home.

At the house, he politely asked the couple to quiet down. The man said, “This is my house, man. You can’t do anything here.” Dean sighed and tried again. “Why doesn’t one of you all go someplace?” No response. Meanwhile, the woman was growing more agitated and was threatening to kill her husband. They were both extremely drunk. Dean didn’t feel good about the situation at all. But after more pleading to no avail, he finally left.

A few blocks away, Dean stopped a man who had run a red light. While he was writing out the ticket, his radio rasped a chilling message: “Shooting at the house on Flamingo. Ambulance en route.” Dean closed his ticket book and told the rather stunned motorist to go on. He sped back to the house and found the wife standing over her dead husband on the front porch.

“I told you I was gonna shoot that man,” she said evenly.

“Well,” Dean replied, groping for words, “I guess you did at that.”

Walking back to the car to call homicide, Dean realized that he had nothing more to say to the woman. He couldn’t even summon up any rage at her. It was the Ragged Edge once again. A policeman had been standing right in the middle of a disorderly and potentially unlawful situation, bereft of the power to do anything about it. A woman had threatened murder, and his only practical response had been to leave and let it happen. He had prided himself on being easygoing, good with people, patient, and tolerant. Now he’d become coarse and cynical, like a tired and sour old man.

He had considered taking the test for a promotion to dispel his gathering malaise; maybe detective work or a desk job would offer new challenges. But he knew he still wanted to be a street cop; the problem was that he didn’t want to be the sort of street cop the public seemed to expect.

Dean might have first thought about quitting one night out on the freeway when he and his partner encountered yet another surly motorist. They were returning to the station when they noticed a man taking some liberties with the speed limit. Dean pulled up beside him and motioned to the driver to slow down. The driver ignored him, and that made Dean furious. “What gall,” he thought. “Here we do this guy a favor by merely warning him, and he ignores us. Does he want a ticket?”

Dean flicked on his Q-Beam, shined it directly into the speeding car, and once again motioned to the driver to slow down. The man eased off his accelerator, and Dean and his partner went on to the station.

They were greeted in the parking lot by the same man, who had followed them. He too was furious. “Don’t shine that light like that at me!” he shouted at Dean. “I’m a citizen.” Dean didn’t say a word; he reached for his ticket book but was stopped by his partner’s hand on his arm. He glanced at his partner, who shook his head and smiled. Dean got the message: Take it easy. It’s not worth it. Dean felt the rage subside within him. His partner was right. It wasn’t worth it. None of it was.

How to Make It Work

Few public institutions have been so resistant to change as law enforcement; that’s due in large part to the military structure of police departments. At the bottom of the ladder is the patrolman, the foot soldier; slightly above him are the detectives and sergeants, then lieutenants, captains, and chiefs. Lines of authority and duty are rigid: patrolmen respond to calls; detectives perform follow-up investigations; sergeants and lieutenants are managers, period. As with all such bureaucracies, a CYA (cover your ass) ethic prevails. Initiative and innovation are not discouraged, but they are rarely rewarded. If there is a political credo in most police departments, it is to mind your own business and not to rock the boat. Getting ahead is based less on initiative and industry than on not screwing up. Thus the motivation to question the priorities and procedures of the department is minimal.

Another deterrent to effective change is the civil service systems that govern most departments. The Texas system, set down in article 1269M, is a prime example. In 1947, when 1269M was enacted by the Legislature, it was intended to purge police and fire departments of the sort of corruption that often comes with political patronage. Cronyism was to be eliminated from the promotion process by basing all decisions on a written exam and the applicant’s accumulated seniority; “arbitrary” factors, including his job performance, were not to be considered. In practice, it turns out that an officer like Dean Nichols, who prefers the streets to a desk job, quickly discovers that following his preference leads him to a financial dead end. The only way to earn substantially more money is to take the test and be promoted to sergeant or detective. The corruptibility of officers was to be eliminated by providing them with almost total job security: if it was impossible to promote an officer for doing a good job, it was also impossible to fire him for doing a poor one.

The intentions of 1269M were noble, but the long-term effects have been disastrous. The average street cop has become cynical about his work because he knows that initiative and hard work won’t get him ahead; middle management is swollen with sergeants and lieutenants who got there on their ability to test well and not necessarily on their potential as managers; police chiefs, who are not even allowed to handpick their department heads, are saddled with management teams who may or may not sympathize with their goals.

Even mayors and city councils have been hard put to change the policies of their departments. The council hires the chief and appropriates the budget, but 1269M prohibits it from doing much else. Obvious and basic reforms have been stymied. Numerous studies have shown, for example, that it might make more sense to allow the responding patrolman to do follow-up investigations on the crimes he’s called to, but civil service systems have tended to keep those functions rigidly separate. Other studies have questioned the need for a so-called military chain of command-officers, sergeants, lieutenants, captains. But that’s what the law requires, so that’s what most departments maintain. Although restructuring a police department might lower the crime rate, it might also destroy the civil service system, which seems more important to a lot of policemen.

The imperative for positive change has never been greater than now. Both Dallas and Houston recently hired young, aggressive, and innovative new chiefs; the responsibility for salvaging law enforcement in those cities rests squarely on their shoulders, and it’s probably not an overstatement to say this may be the last chance we get.

The following suggestions are not a panacea for the problems that plague law enforcement, but they are simple, concrete changes that could make our cops more productive and less inclined to quit.

• The state civil service law, article 1269M, needs to be either radically reformed or scrapped altogether. This is the kind of issue that is frequently ignored during legislative sessions, but it may be one of the most important law enforcement reforms the Legislature has ever considered. Police chiefs need to have the power to appoint their own department heads, rather than being stuck with whatever 1269M’s testing process hands them; the criteria for promotion of street cops need to include job performance as well as the results of a written exam; and police managers need to have more wide-ranging disciplinary authority. A reform package developed by Mayor Kathy Whitmire and Chief Lee Brown, which will be proposed to the Legislature next year, addresses the first two issues squarely. Under the Whitmire-Brown proposal, chiefs would be allowed to appoint their own command staffs from the ranks of the force’s captains and lieutenants with five years’ experience, and performance ratings would account for about 27 per cent of the promotion process. If those sound like piecemeal reforms, that’s because they are. Common sense suggests that job performance should constitute most, if not all, of the basis for promotion, that a chief ought to be able to appoint his mid-level managers, that police management should have much longer than the statutorily prescribed six months in which to take disciplinary action against an officer who has broken the law. But Whitmire and Brown had a hard enough time getting Houston officers to agree to minimal reforms, so it’s a safe bet that legislators, well aware of the political clout of the state’s law enforcement associations, would not be inclined to consider anything stronger. In the final analysis, meaningful reform of police management and personnel practices—and thus police work—will fall to the public, who by local referenda can reject article 1269M altogether, in favor of a more flexible local civil service system. Many argue that scrapping 1269M would invite corruption and cronyism back into our departments, but Dallas made the decision to do without 1269M 35 years ago, and it has the best police force in the state.

• The work pattern and pay scale of the patrolman must be restructured. One reason patrolmen quit is that after four or five years they hit a dead end. They can’t make much more money unless they apply for a desk job; they can’t alter or expand their responsibilities unless they become a detective or some other kind of specialist. A proposal that Chief Frank Dyson, now of Austin, once endorsed was the creation of “horizontal” pay increases and promotions for patrolmen. Patrolmen interested in detective work or management would be free to advance upward to sergeant, lieutenant, and captain. But officers like Dean Nichols, who want to remain on the streets, would be advanced along a horizontal plane with comparable increases in pay and responsibility. Theoretically, a six-year patrolman could make as much money as a sergeant who had been on the force for six years. At the same time, the patrolman’s work should be more varied. One suggestion Dyson has made is that patrolmen be trained in specialties as well as general police skills; they would spend part of the day doing general police work and the rest of it concentrating on a specialty, like crime lab or records. A similar suggestion, proposed by Houston sergeant Tim Oettmeier, would allow the patrolman to rotate through a series of specialties, with intermittent returns to radio patrol.

• Departments must unchain their patrolmen from the two-way radio. The radio is the police officer’s lifeline to the public, but the way it is currently used actually hinders him in fighting crime. Citizens will have to accept that the police cannot treat a residential burglary involving no harm to the victims with the same urgency as an emergency call. Some departments have already begun telling burglary victims that the police will be there, but not for an hour or two. The Houston department is even experimenting with a self-reporting system, in which burglary victims are asked to come to the substation to fill out their own computerized offense reports for insurance purposes, and then go home and wait for a detective to follow up on the case. Other departments—notably Austin’s—have begun to channel the radio patrolman’s other nemesis—the domestic disturbance call—to civilian counselors, who can have more time for and patience with such disputes. Thus far, the experiment in Austin has had encouraging results. Eliminating even a percentage of the simple burglary, auto theft, and minor disturbance calls that the radio patrolman is now responsible for would afford patrolmen more time for proactive, or preventive, patrolling and investigative work.

• Once police departments have the man-hours to devote to proactive policing, they need to approach it aggressively. Public sensitivity to isolated cases of brutality over the past ten years has made departments reluctant to engage in even the most basic kinds of proactive policing: the license check, the stakeout, some forms of undercover work. The question of police authority is a delicate one. None of us wants a police force so powerful that it becomes a danger to the law-abiding public. On the other hand, common sense dictates that the police have to have a fair shot at capturing criminals. Crimes just don’t occur when the police are around, and few are solvable after the fact. The best way for the police to cross paths with the criminal element is to intrude on it. License checks may be a nuisance to the law-abiding citizen, but if they occasionally yield a crook with outstanding warrants or an illegal firearm, it seems a fair price to pay.

None of these changes would be meaningful, though, unless the public rethinks its attitudes toward the police. It’s easy enough blithely to assume that everyone still supports the local police. But the sad fact is that civic responsibility has become little more than an empty slogan, associated with right-wing politics, the gun lobby, and other groups many citizens find distasteful. Nothing could be sillier; if there is one public concern citizens can agree on, it is the need for safe streets and the need for a dedicated, well-trained police force to make them that way. Those are not ideological issues. They are a matter of common sense. There is a single lesson to be learned from the crisis currently afflicting our police forces: Crime is not the police’s problem alone. It’s ours, too.

Turning the Other Cheek

After Dean Nichols resigned, he had another sleepless night or two. His first couple of months as a civilian went well. His progress at the Criswell Center for Biblical Studies in Dallas was steady, and he was able to support his family modestly with part-time work as a security consultant. But then the economy caught up with him; fewer and fewer companies wanted to pay for his services. He had to face the question squarely: should he go back to police work to support his family?

He didn’t know. He certainly couldn’t go back into a big-city police department, but he’d heard about an opening on a small suburban force near Dallas. Maybe he could handle that. The hours and pay would be good, the danger minimal.

The drive to the Balch Springs Police Department was long, so he had a chance to ponder his problem further that morning. Suddenly he knew the answer. He couldn’t do it. He’d dig ditches if he had to, or sell guns. He pulled off to the side of the road, made a U-turn, and drove back to Dallas. Anything would be better than living on the Ragged Edge.

How Safe Are You?

Depends on where you live.

Police chiefs have always done a good job of keeping us ignorant about how their machinery works and about how well it should work. Monthly press conferences with them are about as enlightening as postgame interviews with football coaches, and their statistical reports are tomes full of inscrutable compilations, some of which are based on irrelevant data.

But some of the figures are revealing. Those below, provided by seven major cities, tell us that in Texas the news is largely bad. Crime and violence have increased as the cities in Texas have grown. The state’s metropolitan departments are understaffed and underbudgeted, laden with deadwood at the top, afflicted with bad morale at the bottom, and besieged by problems resulting from the state’s growth over the past decade. Crime statistics in Houston have not been meaningful for two years now, because the Houston Police Department lacks the staff and equipment to process its information in a timely manner. And it is safe to assume that many crimes in San Antonio go unreported because of the city’s large number of undocumented and transient people. Still, there are some hopeful signs, based primarily on the recent arrival of young and aggressive chiefs in both Houston and Dallas.

Using our figures, I’ve listed police departments from best to worst and assigned them stars on a scale of five (excellent) to one (terrible). No department in Texas deserves five stars. Dallas comes closest, with four; it is an excellent department but falls short of greatness because of its manpower shortage. San Antonio, the worst department in the state, doesn’t even get one star. I give it half a star; at least the city now knows that it has problems and can get to work on them.

Dallas

⭑⭑⭑⭑

Dallas is frequently cited as the best force in the state, and by a couple of important measures it probably is. The city’s population is 910,000, and it maintains a force of 2000 officers. Of the state’s five largest police departments, the Dallas force has the highest clearance (arrest) rate, 28 per cent, which is well above the national average of about 20 per cent. That rate is especially noteworthy because it has been achieved despite a 22 per cent increase in reported crime over the past five years, a period during which clearance rates have been declining in most other departments. This record suggests that although the Dallas department may not be reducing the city’s crime rate, at least it is managing crime. The amount of money spent per person per year for police protection, per capita expenditure, is $92, an impressive figure compared to spending in other cities.

The Dallas police force is also one of the best educated among the major city forces, and this has definitely contributed to the relatively small number of complaints about brutality and violation of civil rights. Unlike other Texas police departments, Dallas requires applicants to have a minimum of 45 hours of college credit (Houston, for example, requires only a high school diploma), and nearly half of the 2000 officers have college degrees.

Finally, Dallas has had more stable, higher-quality management over the years largely because the city never adopted the state civil service system, Article 1269M. Under a more flexible local system, Dallas chiefs have been better able to promote truly skilled managers and innovative thinkers to their command staffs, rather than those who simply pass a written exam. Job performance and initiative have played at least some part in the promotion of officers to middle management.

The bad news is that the Dallas force could soon find itself in a lot of trouble if the city management doesn’t begin paying attention to the city’s explosive growth. Calls for service to the department have increased by 43 per cent since 1974, and it has maintained an average response time (lapsed time from when a call is received by police to when they arrive) of 10 minutes, yet the manpower has remained at the same level. Nearly 200 officers left the force last year, 100 by resignation—a sure sign of shrinking morale. The force now deploys only 2.2 officers per 1000 residents, or 5.5 officers per square mile.

The Dallas force’s problems have landed in the office of a new chief, forty-year-old Billy Prince. An eighteen-year veteran with a superlative record, Prince is said to be well liked among the rank and file. That may clear up the morale problems, but the numbers problems won’t be so easy to solve: already Prince has been forced to consider lowering the college credit requirement to obtain a larger pool of minority applicants.

Dallas is an exemplary police department, however—it has maintained its high standards of conduct and productivity despite having a woefully understaffed force.

Austin

⭑⭑⭑ 1/2

This will be an interesting department to watch. Austin’s population, now at 350,000, has grown faster in the last decade than that of any other Texas city. Since 1977, reported crime has increased by 30 per cent; as of 1981, the clearance rate was down to 20 per cent. (Austin Police Department statisticians are quick to point out that this year the department’s clearance rate is 32 per cent.) Nonetheless, the department’s 4.8 officers per square mile, or 1.6 officers per 1000 residents, is a full officer below the national average of 2.7 officers per 1000 residents for cities over 250,000 population (although cities in the Southwest average 1.8). Response time is 5 minutes for emergencies, 9 minutes for other calls.

More encouraging news is that if the Austin department seems undermanned with its 600 policemen, at least it isn’t losing officers as quickly as most other departments. Right now, the per capita expenditure is $73. The department’s officer attrition rate is less than 4 per cent, about half that of Houston and Dallas, and it has done the best job of keeping its force at the authorized level. The only problem is what that authorized level should be: Austin chief Frank Dyson understandably thinks it should be higher, especially since the city is expected to grow by 10,000 residents a year for at least the next five years. Whether the department can keep pace—as those in Houston and Dallas haven’t—is a crucial question. Dyson is known as an innovator, so he may modify the present manpower structure as well as add more officers. The Austin department is already experimenting with a promising “crisis intervention” unit, which employs specially trained civilians to handle domestic disturbance calls—the most time-consuming part of the average patrolman’s day. An innovative force that may prove that smaller forces don’t have to learn the lessons of Houston the hard way.

Fort Worth

⭑⭑ 1/2

The Fort Worth force is at least holding its own. Reported crime decreased slightly over the past year (though from 1977 to 1981 it was up 28 per cent). Particularly impressive was a 5 per cent decline in burglary, a crime that ravaged the city for years. Unfortunately, the department also reported that its clearance rate declined to 17.5 per cent, slightly below the national average. Response time for priority calls is 12 minutes.

Fort Worth does seem to have done a good job of keeping its force abreast of the growth of the city, which now has a population of 385,000, and 730 policemen. Per capita spending is $64. The department’s sworn manpower has increased by a higher percentage than its population over the past ten years. But it still has only 1.9 officers per 1000 population, or 2.9 policemen per square mile. A competent, low-profile force that is managing its crime problem—but perhaps only because Fort Worth is the only major Texas city whose population has remained stable as its force size has increased.

Corpus Christi

⭑⭑

Another city on the cusp of booming growth—and a booming crime problem. Over the past five years, reported crime has increased 25 per cent. The force now has 320 policemen for a population of 230,000. While the force has maintained a 19 per cent clearance rate for major felonies, the department has not anticipated the city’s growth. It deploys only 1.4 officers per 1000 residents or 3 policemen per square mile, and its per capita expenditure is only $60—well below even Houston. Moreover, the department doesn’t even keep figures on the average response time. A force that could go from fair to poor within a year if it doesn’t wake up.

El Paso

⭑⭑

Like Austin and other medium-sized Texas cities, El Paso managed to escape serious crime problems through the sixties and early seventies. No more. The city has ballooned to about 440,000 in population and 240 square miles in area. Reported crime is up 20 per cent since 1977, and citizen calls for service are up 50 per cent. Response time is not available, and, unbelievably, the department has not yet computerized its dispatch system. Now with 645 policemen, the department has actually lost 10 per cent of its force, leaving it with fewer than 1.5 officers per 1000 population, or 2.7 officers per square mile. The clearance rate is 25 per cent. One measure of how far behind the city’s growth the department has fallen is that it must now cover an area nearly twice that of Austin—with roughly the same number of men. One big problem in El Paso is money: except for San Antonio, it had the lowest per capita expenditure, $53.

Houston

⭑ 1/2

The state’s largest force—3500 police officers for a population of 1.7 million—has probably suffered enough for the outbreak of police brutality that put it on the map in 1977. But it is worth pointing out that even as recently as last year, Houston cops were not exactly sparing the rod. According to one study, the department still employed deadly force at a higher rate than any other department in the state, and in Justice Department investigations of civil rights violations, Houston ranked fifth. It’s also only fair to add that such dubious achievements are probably due to the sheer frustration of being in Houston. Over the past five years, the force has not been able to keep pace with the city’s growth. The Houston force deploys 2 officers per 1000 population, or 5 officers per square mile, fewer than any other of the nation’s eight largest cities; also low is Houston’s per capita expenditure of $75. The impact of these figures has been measurable. Reported crime has risen 30 per cent since 1977; the clearance rate is down to 11 per cent. Houston does not break out a separate response time statistic for emergency calls; the department’s average response time exceeds 30 minutes. The situation has become so acute that the department, in effect, has not been able to enforce traffic laws over the past year and victims of residential burglaries in which there was no bodily harm have recently been asked to report the crime by filling out a computer form at their local substation describing the incident.

The man with the unenviable task of cleaning up the mess is newly hired chief Lee Brown, formerly in charge of the Atlanta force and now Houston’s first black chief of police. Brown’s early months were predictably stormy: rank-and-file cops were not sure they liked taking orders from an outsider, and when Mayor Kathy Whitmire proposed radical changes in Article 1269M, the state civil service system that governs the department, there was talk of mass resignations. To his credit, Brown remained calm and managed to bull his way through some of the early resistance. Working with Whitmire, he hammered out a compromise on civil service reform. Another indication that he has his priorities straight was his order that three hundred officers chained to useless desk jobs be shifted back to the streets over the next three years. Finally, Brown has commissioned studies of Houston crime patterns and demographics to determine just how many officers the city needs and where and at what times they should be deployed. Such questions may seem fundamental, but no chief has bothered to ask them before. In short, while the Houston department remains riddled with poor morale and inefficiency, the Brown regime is at least talking a good game—which in Houston has to be counted as a big step forward.

San Antonio

1/2

For years, the San Antonio Police Department remained as out of sight and mind as did the San Antonio River before the developers discovered it. Recently the city commissioned Arthur Young & Company to do a study of the department, and that study revealed many serious problems. The city’s population is 785,000, and it has a police force of 1100 officers. This means there are 1.4 policemen per 1000 population, or 4.1 policemen per square mile. Sworn police manpower has actually decreased over the past 10 years, reported crime was up by 12 per cent, and the clearance rate was 17 per cent. From 1946 to 1981 crime multiplied tenfold, while the police force only quadrupled. Given that Houston clears 11 per cent of its reported crimes and that crime there rose 30 per cent in five years, the San Antonio figures seem implausible. The study also revealed incredible discrepancies in the record of arrests.

Sixty per cent of the officers said morale was poor; only 17 percent said management was good. More than a third complained that their patrol cars were in poor condition. San Antonio’s per capita expenditure of $45 was by far the lowest of major Texas cities. The patrol division was nearly 100 officers short of its authorized level, and response time information was lacking because patrolmen were not calling in when they got to their destinations. The study found that the San Antonio department was beleaguered by obsolete management systems, inefficient use of resources, and shoddy record keeping.

The study detailed the stagnating effects of the state civil service law on the management ranks of a police department. The average age of the department’s deputy chiefs and captains was 48 years, and each of them had held his rank for more than 7 years, suggesting that even if someone had been aware of the department’s problems, he would have been hard put to do anything about them. As for the future, it’s doubtful that San Antonio residents were heartened by Chief Robert Heuck’s initial response to the study. “So far, there’ve been no major surprises,” he told a reporter. “We’ve known about most of these problems for years. We haven’t been sitting here with blinders on.” Maybe not, but unless someone does something soon, San Antonio could be the Houston of the eighties—if it isn’t already.

J. A.

The Secret Weapon

Little things make a cop’s car smarter and safer than yours will ever be.

The distinguishing feature of the police squad car used to be that it could blow anything else on four wheels off the road. No more. Because Detroit has stopped making big four-hundred-cubic-inch “muscle” engines and because the police are using helicopters and other modern technology to track fleeing suspects, the contemporary squad car is designed less for raw power and speed than for economy and maneuverability. And with the advent of in-car computers and other exotic gadgetry, what’s under the hood will be even less important in the future. The Houston Police Department’s fleet of 1982 Plymouth Furies and Fords exemplifies the trend.

Radio

A twelve-channel, three-way (car-to-station, station-to-car, car-to-car) Motorola. This innocuous-looking gadget is at once the police officer’s most valuable link to the world outside his car and the bane of his daily existence. At its best, the radio can transfer a call for help fast enough that the officer can actually get to a felony while it is still in progress. At its worst, the radio is a hissing, crackling nemesis that constantly interrupts his attempts at proactive (preventive) patrolling with non-emergency calls.

Seat Belts

Standard shoulder harnesses.

Door Locks

Standard locks on front doors. No locks on back doors or window handles. Doors can be opened only from outside.

Computer Terminal

Experimental equipment on only a few squad cars. But immediate access to both local and national crime computers is an intriguing idea. If used properly, these portable computer terminals can allow a team of police officers to engage in proactive policing even while they are answering nettlesome calls from the public. The experimental terminal being used by the HPD gives officers immediate access to significant information about a suspicious-looking car. The officer has only to punch the license number and, presto, he has at hand outstanding warrants, status of car, even criminal record of operator. Since getting such information by radio can take as long as thirty minutes, it’s not hard to see how the police could significantly increase their contact with the criminal element just by learning the computer keyboard.

Cage

Glass or steel-mesh screen that separates suspects from the driver.

Flashing Lights and Siren

The sole remnants of “muscle.” The flashing reds and loud, whooping siren were originally intended to make police presence in the community not just apparent but awesome and intimidating. That may still be necessary in the case of a high-speed chase (rare) or a mad dash to a felony in progress (rarer), but many in law enforcement have begun to question the need for lights and siren in proactive patrolling. Rather than deterring crime, the unmistakable “cherry top” of the squad car has made the police so obvious that crooks have little trouble figuring out where not to do their business. Using unmarked cars for patrol is becoming more common; in fact, unmarked sedans already make up more than a third of the HPD fleet.

Engine

A modest 302 cubic inches. Does have a four-barrel carburetor for increased performance, as well as specially designed cooling and electrical systems (the former because squad cars must idle for such long periods, the latter to power the radio, lights, and siren). Still, on a straight stretch of the Gulf Freeway, this sedan would be eating the dust of a Porsche or a Trans Am.

Suspension

All squad cars include a “police-taxi package” underneath the car. In general, the chassis of a squad car is like that of a truck: heavy-duty suspension, rear and front-end sway bars, heavy shocks, custom-made fabric-belted radial tires, heavy-use brakes. The police-taxi package helps to compensate for the car’s lack of power by providing increased maneuverability. The change of emphasis has radically affected police pursuit. Rather than trying to overtake the fleeing car (an impossibility anyway because of traffic), the modern police officer tries to keep it in view, so he can get the license number (which can quickly be run through the department’s central computer, producing the driver’s name and address; an arrest can be made later if necessary) or so a helicopter can pick up the chase.

Trunk

The police officer’s medicine cabinet. Includes a fire extinguisher, a first-aid kit, a shotgun and rack, road flares, and other incidentals; also houses the amplifier for the radio.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Police

- Crime

- Houston