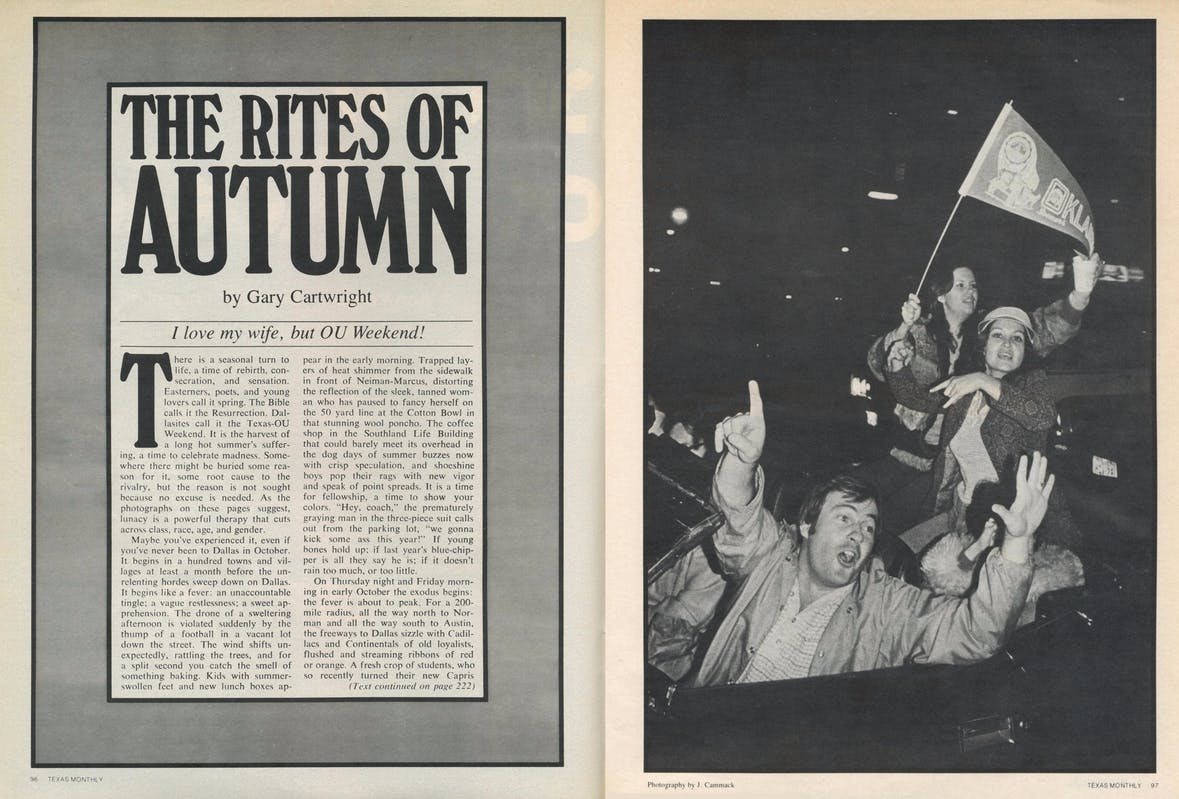

There is a seasonal turn to life, a time of rebirth, consecration, and sensation. Easterners, poets, and young lovers call it spring. The Bible calls it the Resurrection. Dallasites call it the Texas-OU Weekend, it is the harvest of a long hot summer’s suffering, a time to celebrate madness. Somewhere there might be buried some reason for it, some root cause to the rivalry, but the reason is not sought because no excuse is needed. As the photographs on these pages suggest, lunacy is a powerful therapy that cuts across class, race, age, and gender.

Maybe you’ve experienced it, even if you’ve never been to Dallas in October. It begins in a hundred towns and villages at least a month before the unrelenting hordes sweep down on Dallas. It begins like a fever: an unaccountable tingle; a vague restlessness; a sweet apprehension. The drone of a sweltering afternoon is violated suddenly by the thump of a football in a vacant lot down the street. The wind shifts unexpectedly, rattling the trees, and for a split second you catch the smell of something baking. Kids with summer-swollen feet and new lunch boxes appear in the early morning. Trapped layers of heat shimmer from the sidewalk in front of Neiman-Marcus, distorting the reflection of the sleek, tanned woman who has paused to fancy herself on the 50 yard line at the Cotton Bowl in that stunning wool poncho. The coffee shop in the Southland Life Building that could barely meet its overhead in the dog days of summer buzzes now with crisp speculation, and shoeshine boys pop their rags with new vigor and speak of point spreads. It is a time for fellowship, a time to show your colors. “Hey, coach,” the prematurely graying man in the three-piece suit calls out from the parking lot, “we gonna kick some ass this year!” If young bones hold up; if last year’s blue-chipper is all they say he is; if it doesn’t rain too much, or too little.

On Thursday night and Friday morning in early October the exodus begins: the fever is about to peak. For a 200-mile radius, all the way north to Norman and all the way south to Austin, the freeways to Dallas sizzle with Cadillacs and Continentals of old loyalists, flushed and streaming ribbons of red or orange. A fresh crop of students, who so recently turned their new Capris toward these bedrocks of education, turns now toward Dallas, knowing that everything in between was temporary, a mere prelude to Texas-OU Weekend. At the stroke of Friday noon, in the exact geographical center of downtown Commerce Street, along the wide, crooked intersection between the Baker Hotel and the Adolphus, they will converge like two tribes on the eve of battle. A thousand auto horns will honk simultaneously and without interruption, signaling to the hundreds of others who are there out of stubborn curiosity, or because they have been trapped in the combustion, that the war council has begun; nothing else will be tolerated.

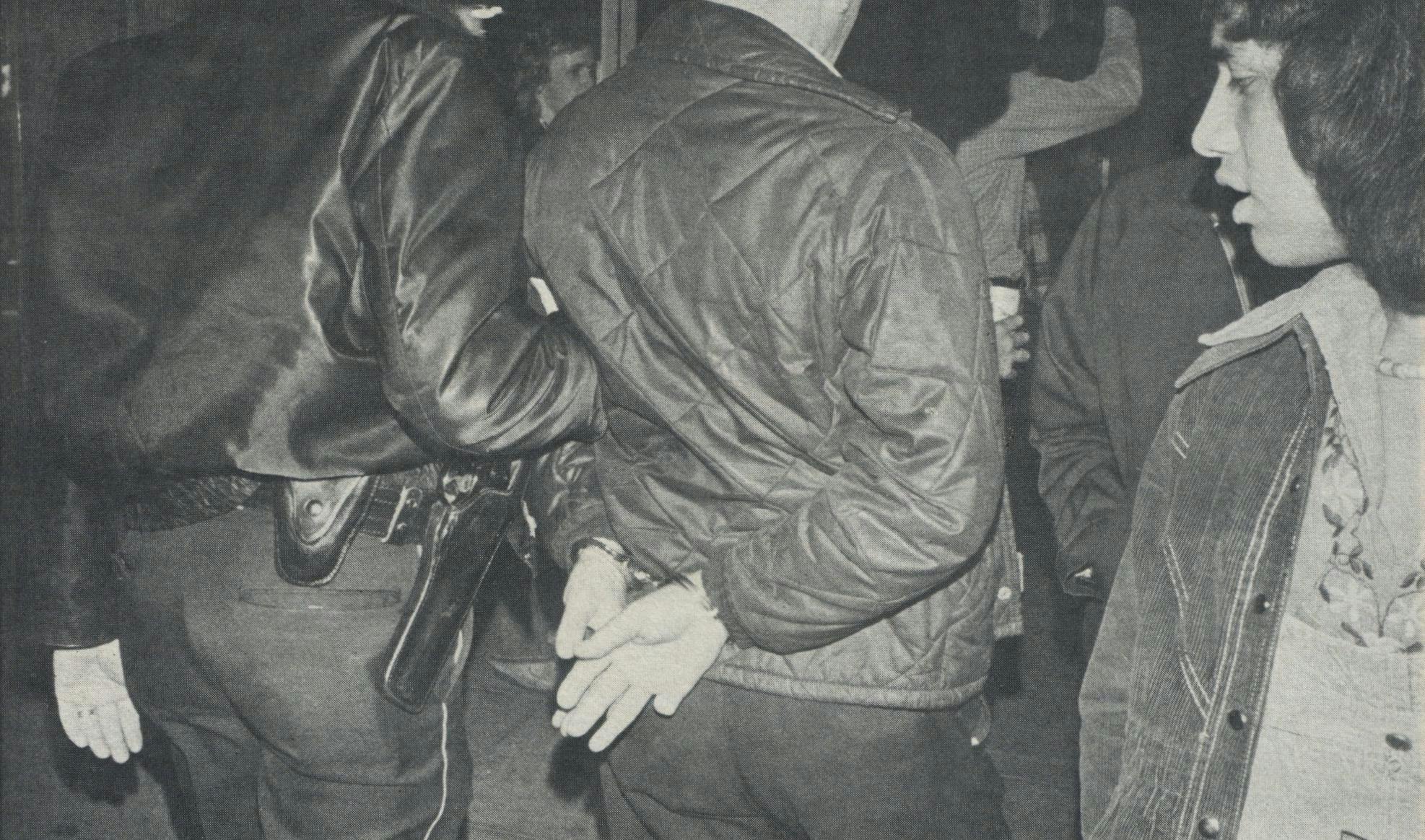

Every hotel, guest bedroom, and spare sofa in the Metroplex has been claimed for months. In the case of many of the merrymakers, there would be nowhere to go even if they wanted to, which no doubt many do. Until a few years ago Dallas police helped solve the hotel problem by throwing hundreds of revelers in the city slammer, but in recent Texas-OU Weekends a wall of riot-helmeted police has managed to preserve order and even a trace of decorum: since it would be nearly impossible for police paddy wagons to maneuver the bumper-to-bumper traffic, this is both practical and socially prudent. Ticket scalping is a problem, but nothing like it used to be. All 72,000 Cotton Bowl seats are long gone, a portion of them to students but the bulk to the old loyalists with powerful connections. The best way to get a ticket to the game is to read the obits. Here at the hub of the tribal camps on Commerce Street, tickets are a small concern. Texas-OU is not a game, it’s a celebration masking as a conflict. Mardi Gras without Lent. Lauderdale without sand fleas. A parade without bands, floats, or twirlers. A parade where the judges wear riot helmets.

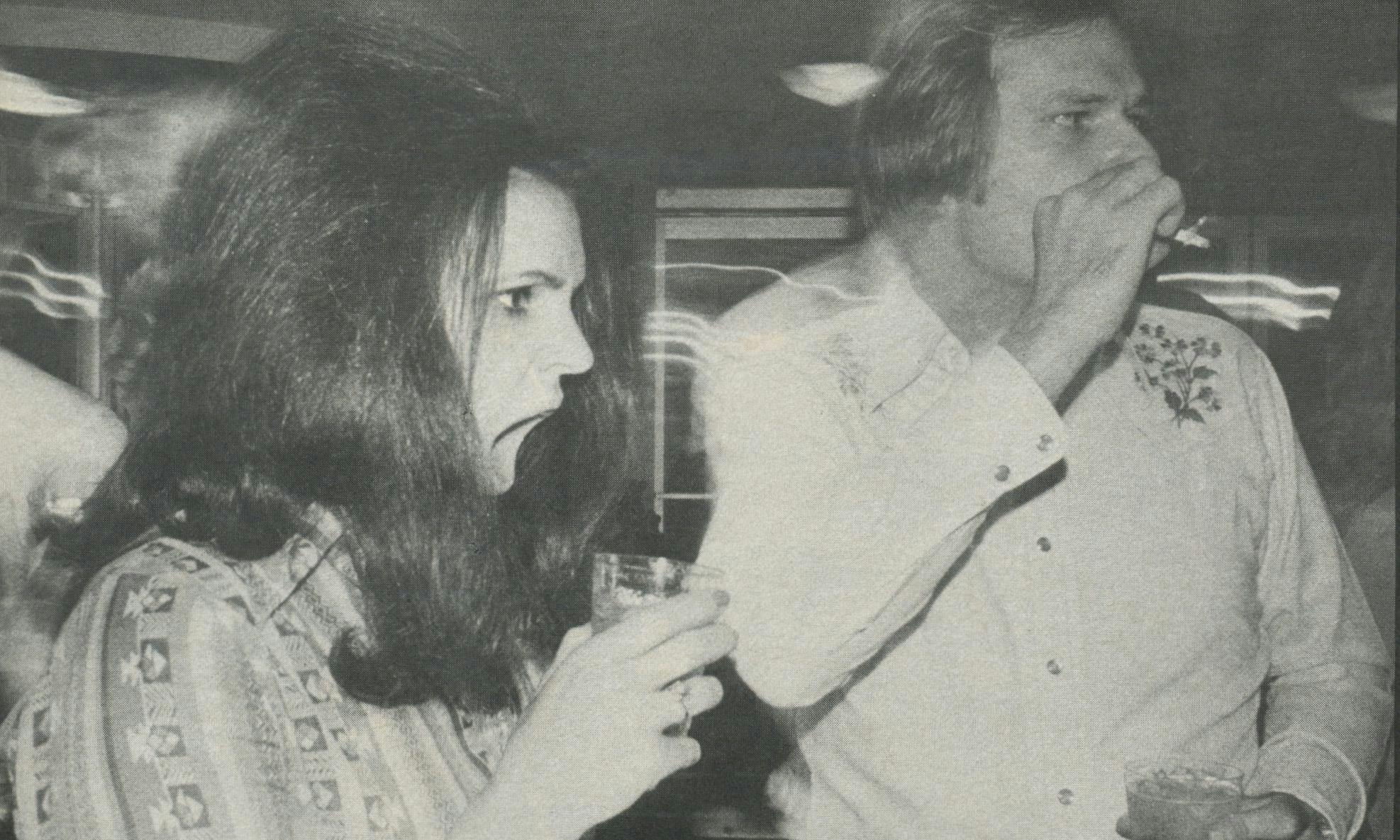

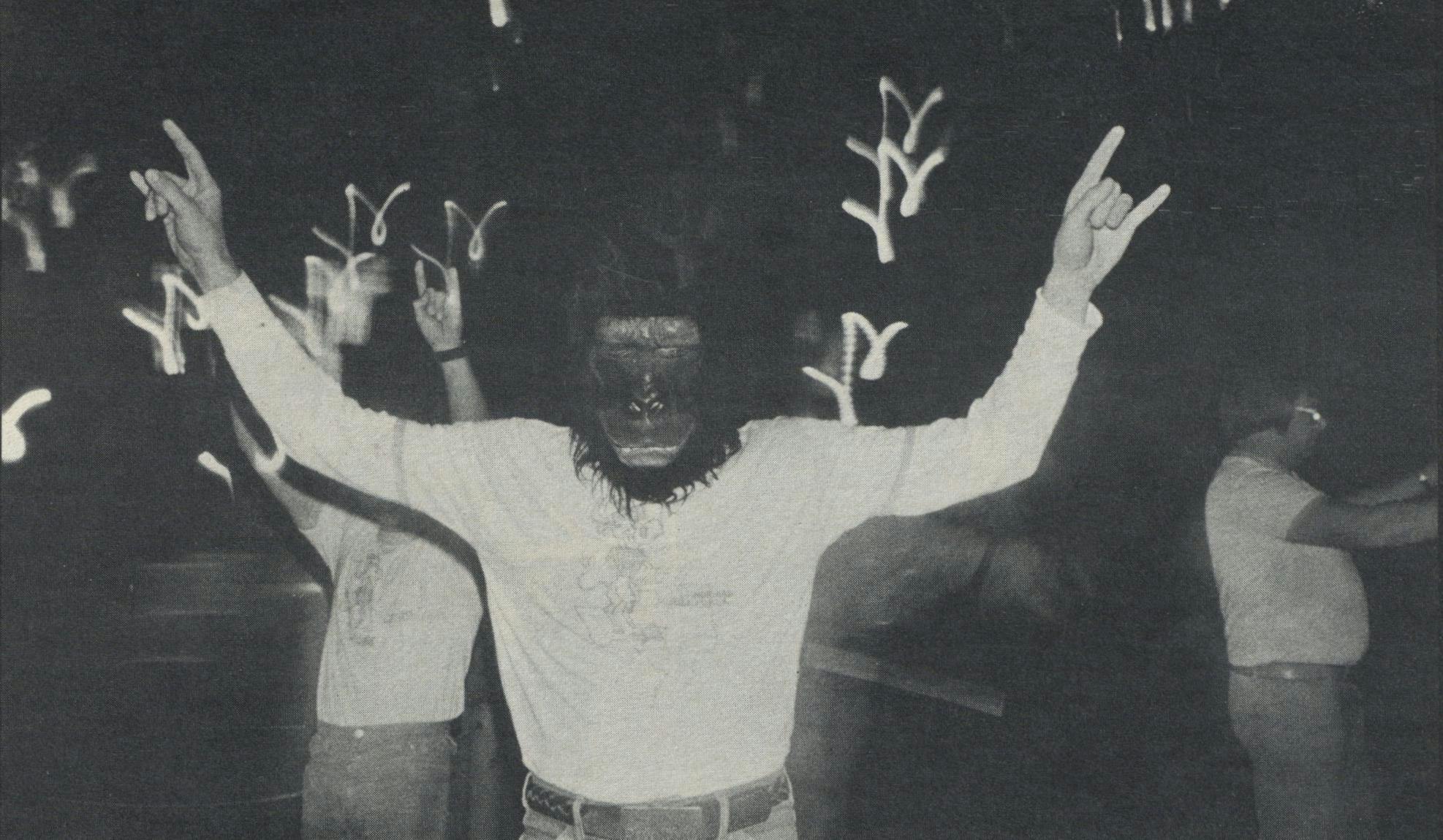

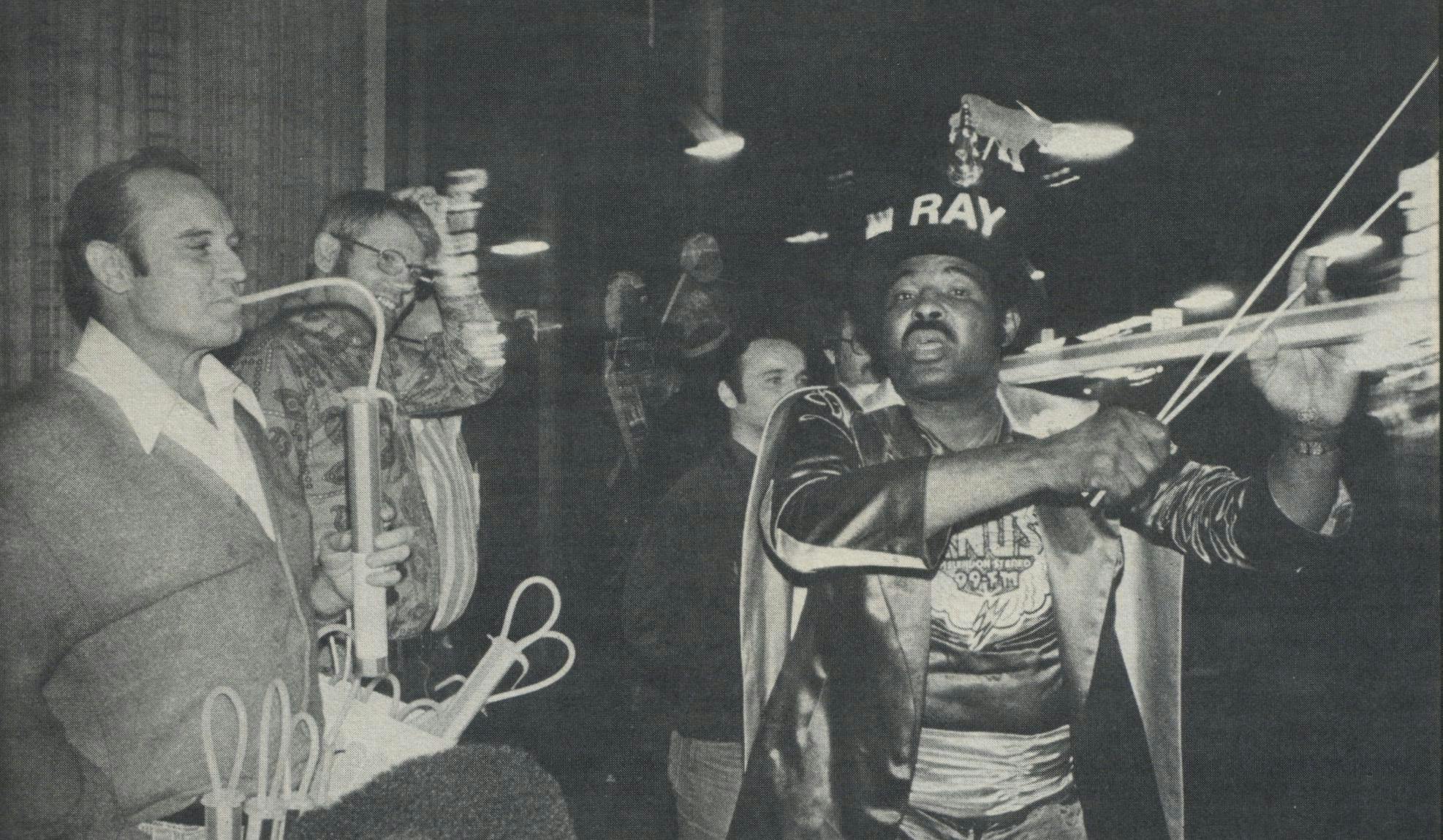

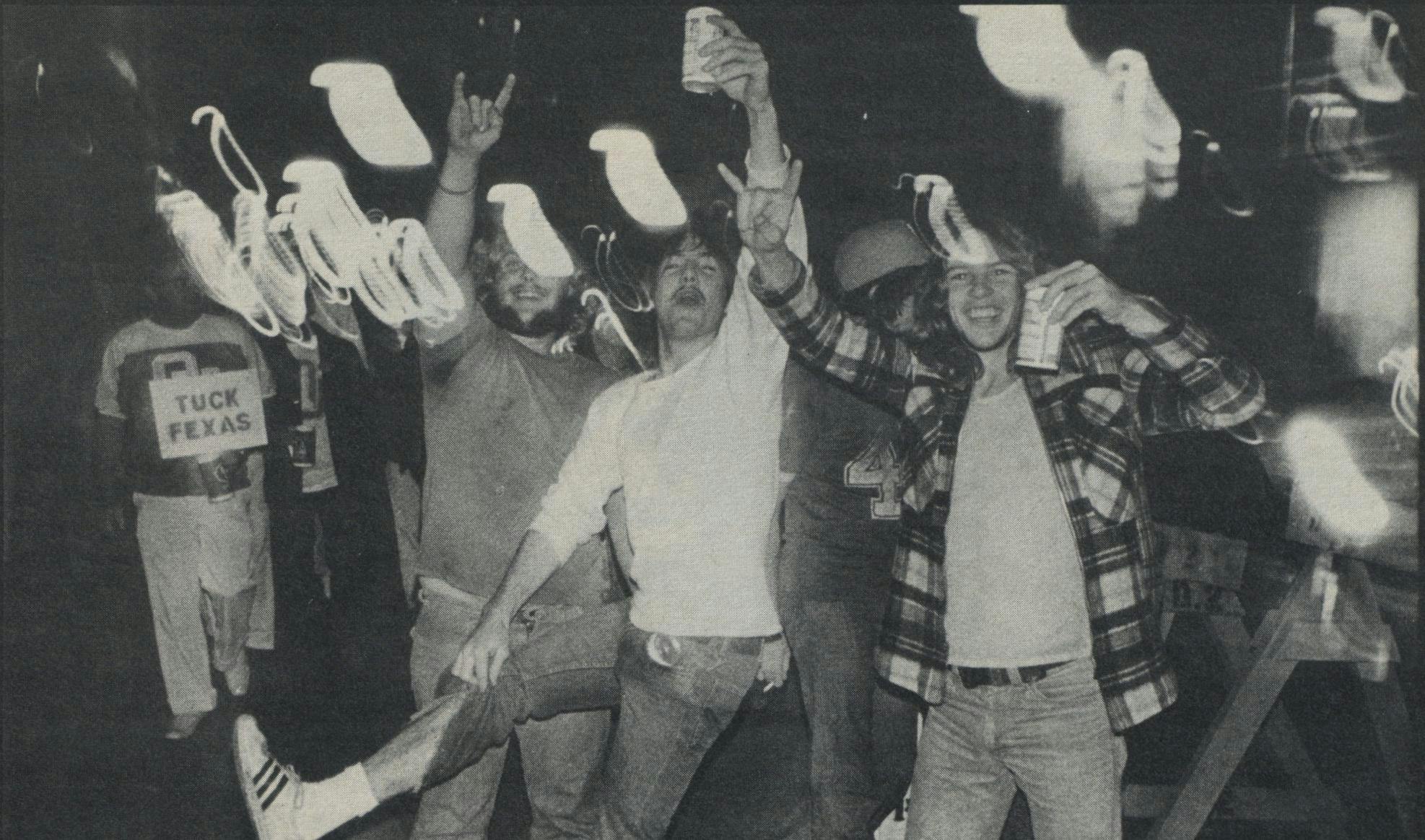

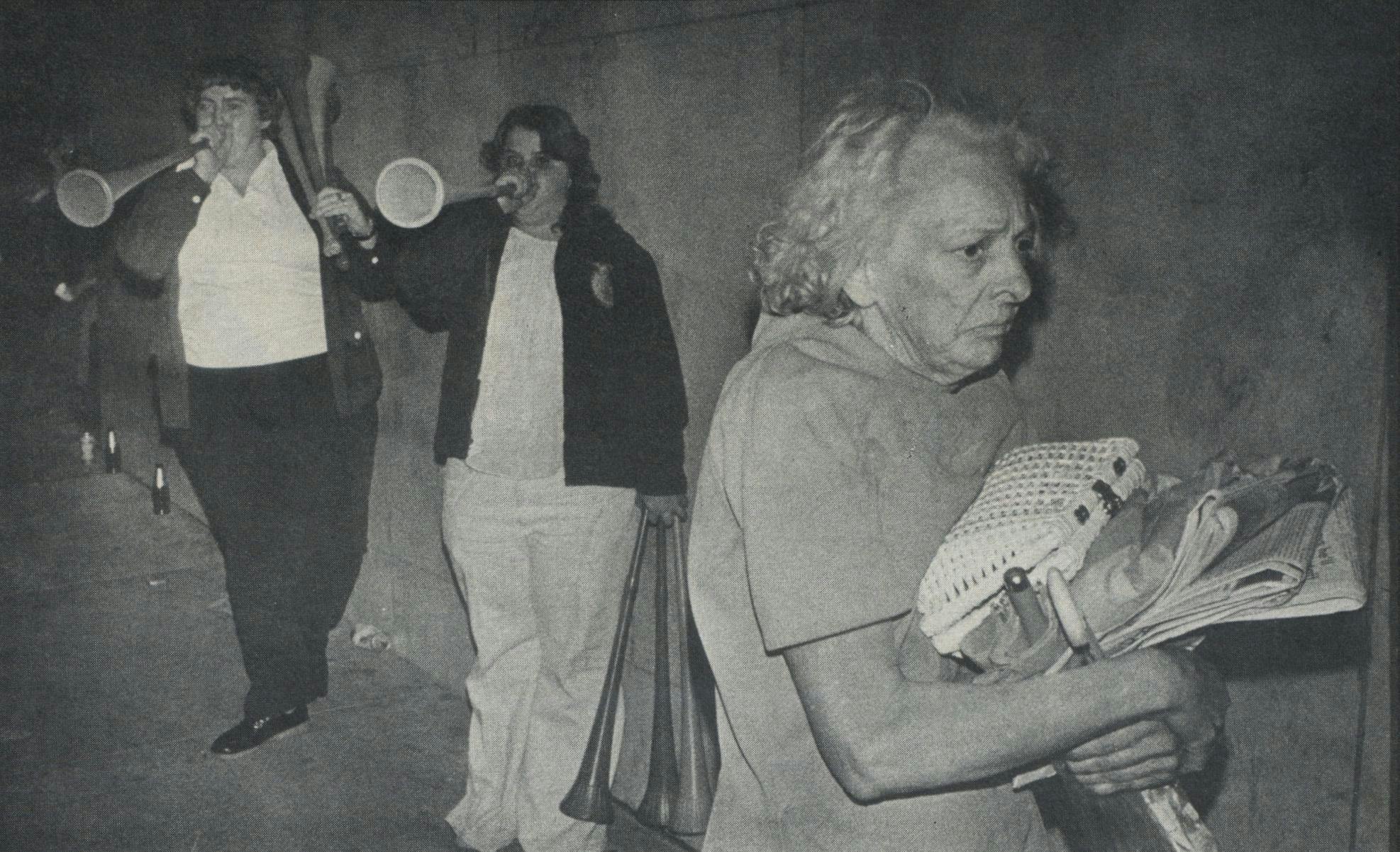

When the broiling October sun slips behind the skyscrapers and neon streaks the night, the tribes advance, but not on each other. It is not so much a promenade as a dance. Like satyrs in a concrete dell, they sway to the trumpeting of plastic horns, auto horns, whistles, proclamations, invectives. A speaker mounted to a van plays Boomer Sooner, and another speaker somewhere answers with Texas Fight. A darkhaired girl with a wide mouth shouts that Longhorns are large shit factories, and her counterpart in orange retorts that anyone who would claim to be a Sooner would also squat on a bull nettle. A crowd circles a plastic wastebasket, dipping paper cups of Purple Jesus, a potion consisting of many parts alcohol to one part grapejuice. Good-hearted strangers lean from hotel windows, lobbing cans of beer to grateful passersby. The bars and topless joints are doing business, but it’s a revolving business, turning them in and out like a soup kitchen. Pickpockets, hookers, dope dealers, and free booters are typecast with the mob, trading commodities, and funny looks. Girls in T-shirts and tight sweaters spew each other with warm beer, then stagger arm in arm, laughing. A child hugs her mother’s leg and tries to cry, but it’s not easy with the man in the monkey suit dancing around her.

On the parking ramp outside the Statler Hilton a grizzly sourdough in a soiled cowboy hat mounts his Model-T with the customized rear suspension, rearing it up on its hind wheels and riding it like a bucking horse. A transient steps off a Greyhound at the Commerce Street depot, blinks, and decides that purgatory, if indeed that is what he has encountered, isn’t such a bad place. There will be some fights, a few of them serious, but a strange magnet of accord grips this crowd. They are not here to fight—the Cotton Bowl is for fighting—they are here to look and laugh and be seen. It’s a place they’ve heard about, a citadel of anarchy and supercharged particles. It’s a place to find a new love, or lose an old one. A place to make for yourself, a place to prove you’ve been.

The night goes fast, like black powder. They’ll push and drink and love and fall down and do things they never dreamed, but it’s okay. Somehow they know it’s only a frame in time. Somewhere, there is a floor to sleep on. Somewhere, there is something else, something new, something better. Sometime before dawn they will go to their places and, except for a few roving bands looking for the Texas School Book Depository, the streets will be deserted trenches of rubble.

The broiling sun will reappear on Saturday, claiming the weak, testing the strong, shimmering and swimming over the dizzy jam of vehicles and pedestrians inching along every artery to Fair Park. The 72,000 football fans will be a vocal minority, but a minority, nevertheless. According to tradition, there will be a football game; but the bulk of the tribe will sleep through it, preferring that the outcome speak for itself. When the game has been decided, the victors will parade back down Commerce, honking horns and waving banners, and the losers will seek air-conditioned rooms and begin mixing drinks. By Saturday night the freeways will already be clogged, north and south. A righteous few will already be talking about next year, but the tribe will relive Friday night and maybe pray for Sunday morning. To hell with next year.

- More About:

- Sports

- Photo Essay

- Higher Education

- Football

- College Football

- Dallas