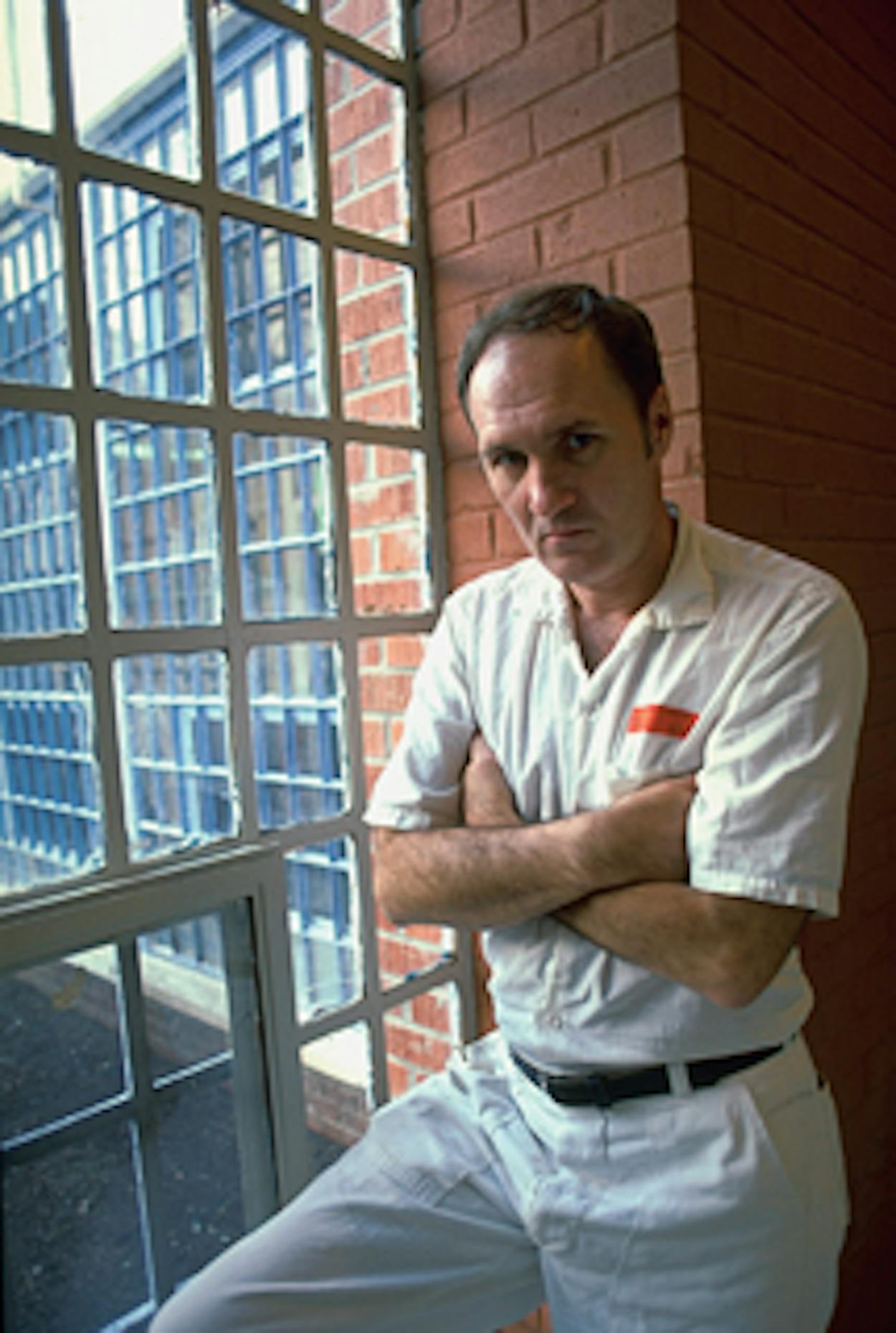

About a year ago, it was reported that Randall Dale Adams had died, bringing to a close one of the more tragic stories in recent Texas history. A construction worker from Ohio, Adams (pictured here, in 1989) was convicted and sentenced to die in 1977 for the murder of Dallas police officer Robert W. Wood. He spent twelve years behind bars—and, in 1979, came within three days of being executed—before being released in 1989 after the key eyewitness recanted his previous testimony. The story was brought to widespread attention by the landmark documentary The Thin Blue Line, and Adams’s case became a rallying point for advocates of criminal justice reform. But after a few years of speeches and television appearances, he mostly shunned the spotlight, and by the time he died he was living in complete obscurity. When his obituary ran last June, he had already been dead for eight months.

For a time, Adams was the public face of wrongful convictions, but that dubious mantle has long since passed on to others who suffered a similar fate. Most recently, it has belonged to Michael Morton, a Williamson County man who served nearly 25 years for murdering his wife—a crime he did not commit—before being released last fall. This was one year after the release of Anthony Graves, who had been behind bars for 18 years for a brutal multiple homicide in Somerville—a crime that Graves had absolutely nothing to do with. There have also been scores of less-high-profile cases. Nearly fifty men have been exonerated and set free in Texas since 1989 using modern DNA testing on evidence collected at the crime scene. Last month, two more joined this list, James Curtis Williams and Raymond Jackson, both of whom spent almost 30 years locked up for a crime they did not do.

Texas leads the nation in the number of such cases. Our criminal justice system is vast, and most of the people who work within it, from cops to judges, do an exceptional—and exceptionally difficult—job. Nonetheless, the consensus has been growing that we have a problem with wrongful convictions. In view of this, we consider it an unhappy and yet vital part of our job at TEXAS MONTHLY to continually ask two simple questions: Why does this keep happening here? What can be done to stop it from happening again?

Two stories in this issue attempt to provide some answers. The first is a roundtable discussion with six people who know our criminal justice system intimately: a police chief, a prosecutor, a district attorney, an appeals court judge, a state legislator, and Anthony Graves himself. We brought this dynamic group together around a dinner table and asked them to talk about Texas’s criminal justice system—in particular, prosecutorial misconduct, questions of which have come up in both the Graves and Morton cases. The result was a fascinating conversation that illuminates some of the good work that is already being done to make our system more fair, as well as highlighting how far we still have to go (“Trials and Errors”).

One of the common refrains you hear when discussing cases like Graves’s and Morton’s (and Adams’s) is that the convictions were won decades ago and things are better now. They certainly are, but another story in this issue puts the lie to that too-easy explanation. On the same night that we convened our roundtable in Austin, executive editor Pamela Colloff was in Nueces County to report on a dramatic hearing that could result in a new trial for Hannah Overton, a Corpus Christi woman sentenced to life in prison for the death of her foster son in 2006. Readers will recall Overton from a lengthy feature story in the January issue (also by Pam). A month after that article came out, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals ordered the original trial court to hold an evidentiary hearing to look into questions about the state’s case. Pam’s dispatch from that hearing (“Hannah’s Prayer”) makes clear yet again that there is ample reason to doubt that the verdict reached was the right one. It does not seem unlikely that before long, Overton too could wind up on the rolls of the wrongly convicted, alongside Morton, Graves, Adams, and far too many other Texans, living and dead, who suffered the greatest injustice imaginable.