Five minutes away from 6:30 p.m., eastern standard time, three of the four seats in the CBS News control room are still empty. In the occupied seat, a tall, gaunt quiet man of about 50—the chief engineer, formerly known as the technical director—confronts a flashing yard-square panel of buttons, switches, and erratic meters. There seem to be over a hundred pulsing, mysterious buttons between his outstretched arms, and he appears very intent upon them.

The engineer and his panel sit to the far left of the short, curved control booth, where he peers out over a bank of knobs through the darkness toward a seemingly distant and highly unlikely vista. The distance is illusion, caused by the myriad shimmering, key-lights illumining the booth. Actually only five feet away, the vista is a massed wall of television screens—twenty-two in all—clustered around an imposing clock with a sweep second-hand. The whole place might have been designed by Stanley Kubrick. According to the clock, there are now four minutes until 6:30, yet the three seats remain empty.

A hundred feet, two corridors, and half-a-dozen doors away, the most trusted man in America sits at another desk, also curved but much less impressively ornamented. On its front it carries the familiar logo of the CBS Evening News. Mounted behind him is a wall-sized Mercator projection of the globe. As he sits there, shuffling his papers, and drinking tea with honey from a Styrofoam cup, he is visible on four of the control room screens, two in color and two in black-and-white.

The other men arrive at the three-minute mark, from different directions, to claim their seats in the booth. All three are young—the oldest might be 35—and they all move with quick, deliberate assurance, talking in soft, rapid bursts that seem equally assured. They are the director, his associate, and a senior producer. Each of them dons a headset and places in front of himself identical scripts of large type on yellow paper.

“Two minutes to air,” calls the engineer.

The man in the other room takes a swallow from his tea and conceals the cup behind the ledge of his desk. A makeup expert approaches to dab his face with powder and brush his hair while he asks a question of one of his writers. The question is unheard in the control room.

“Gimme tight,” barks the director into his headset.

On one of the small corner screens, the man at the desk looms suddenly large as the camera focuses down on him. There are two cameras trained on him, one near and straight-on, the other farther back and at a three-quarter angle. The cameraman sets his focus on the man’s brow—revealing large, expressive blue eyes—then pulls back to frame a conventional close-up.

The man wraps the cord for a small lavaliere microphone around his neck, snaps it, and tucks it beneath his tie.

“Sixty seconds,” warns the engineer.

On the largest of the screens, the one in the middle labeled MASTER, a detergent commercial is running soundlessly. There are no sounds from any of the screens—there is only the hurried but confident chatter of whispers and orders from the men watching them.

“Cue tape,” demands the director.

“Thirty seconds,” says the engineer.

The man at the desk sneaks a last furtive sip of tea and stands to put on his coat.

“Where’s Schieffer?” asks the director, glancing over his script.

“Seven,” answers the assistant.

On the screen marked 7, White House correspondent Bob Schieffer noiselessly addresses his microphone.

The clock glares back malevolently from five feet away, its quickest hand sweeping briskly, relentlessly.

“Twenty seconds,” the engineer signals.

“Ready to mat,” says the director.

From screen 4, the CBS Evening News logo is superimposed on the small screen showing the man at his desk. He calmly buttons his coat, checks his French cuffs, pulls a small comb from his pocket and slips it through his recently brushed hair.

A woman is holding a box of soap on the MASTER screen.

“Ten seconds.”

“Ready to roll.”

The man sits down, leafs through his script.

“…seven, six…”

“Hit it.”

The man appears instantly on the MASTER screen, still perusing his papers as the Number Two Camera tightens slowly and dollies across.

“Tape. Mike.”

“From the CBS Newsroom in New York . . .” intones an invisible, metallic baritone, backed pretentiously with strings and faint piccolos.

“…two, one…”

The man looks up.

“Cue him.”

“Good evening,” says Walter Cronkite.

We bought our first TV set, I recall, at my adamant insistence and barely in time to see Don Larsen throw his perfect game in the 1956 World Series. I suppose that’s when Walter Cronkite first came into my life, though in retrospect he seems always to have been there, some part of the blood’s inheritance, like left-handed genes or original sin.

In 1956 he was hosting the You Are There show, a weekly series of re-enactments wherein CBS correspondents would track down and interview people like Louis Pasteur, Benedict Arnold, General Sherman, and so on. Walter would narrate as these people performed surgery, committed treason, plundered towns, whatever they did when they weren’t being interviewed. He was very good at this, and I began to regard it as perfectly natural for Walter to be There, whenever and wherever There was.

As I grew older, I came to realize that, sure enough, Walter always was There: assassinations, investigations, coronations, launches, landings, you name it. Past all the benchmarks and the tombstones of the late Fifties and early Sixties, Walter was faithfully on hand to counsel or commiserate or, sometimes, to cry and cheer, even as all of us cried and cheered.

I remember that windy afternoon when a rifle bullet ended innocence forever. They told us in study hall that the President had been shot and critically wounded, and that we could all go home. I fled directly to our TV set, hoping desperately that it wasn’t true; it couldn’t be true, I told myself, unless Walter said it was.

It was true, of course. But Walter was there, as I knew he would be, trying to make sense out of madness. He had no script, no authoritative sources, no cues or clues or hints of promise, no word, probably, that I didn’t have myself. He was dressed in shirt-sleeves, as I’d never seen him before or since — he wasn’t aware that he’d forgotten his coat until hours later — his forehead sweaty and his furry eyebrows nervous and betraying anxiety. When word finally came that the President was dead, he choked and turned away from the camera; and I knew before he told me. Only much later did I come to understand that the genuineness of that gesture imprinted itself forever upon a generation of Americans and enabled Walter Cronkite to become a national institution. For a brief moment he let us see what we always suspected: that the experts are as vulnerable and confused as the rest of us. He was on camera for four straight hours that night, ad-libbing mostly, repeating himself to the point where things ultimately started, if not to make sense, at least to sink in. As stray facts arrived, Walter explained their significance and fitted them in place, imposing a skein of sanity and order on a time of utter chaos, holding it all together. By the time it was over he was visibly exhausted.

Looking back on it now, from a dozen years hence, I’m sure it was Walter who carried us through that long, awful day and night. More than the oath-taking or eulogizing, more than all the parades, platitudes, pieties, more even than the Constitution itself, it was Walter who was truly there, telling us the way it was, fashioning history from a furious nightmare. It was as if he were still narrating You Are There, except that suddenly he and all of us really were.

“Tape reset,” orders the director.

“Reset seven,” replies the associate director as news correspondent Tom Fenton materializes on screen 7, where Bob Schieffer had been a moment earlier. Schieffer is now on the MASTER screen, talking inaudibly about Gerald Ford’s trip to Boston. “This goes a minute five,” says the producer.

“Forty seconds left,” advises the engineer. “Ready to key.”

“Key it,” says the director.

On the small screen where Cronkite is stealing another sip of tea, a bright yellow background — a chroma-key — replaces the Mercator projection that, down the hall and around the corner, is actually still behind him. Superimposed on the yellow background is an intricate, full-color map of Jerusalem.

“Cue tape.”

“Fifteen seconds.”

“Okay, cue him.”

Cronkite hides his cup once more, checks his place in the script and looks into the camera.

“. . . five, four . . .”

Schieffer is signing off from the White House lawn.

“Hit it.”

Cronkite, complete with yellow background and map of Jerusalem, leaps into the MASTER screen, saying, “A bomb exploded today . . .” Bob Schieffer has disappeared utterly.

“This is three sentences,” remarks the producer.

“. . . seven, six . . .”

“Roll it.”

On small screen 7 the videotape leader begins to unwind, a maze of dark lines and test patterns with large numbers counting off: 5, 4, 3 . . . It takes seven seconds for videotape to roll to the right speed.

“And now we have a report,” says Walter Cronkite, “from correspondent Tom Fenton in. . .”

“Hit it.”

Tom Fenton seizes the MASTER screen, claiming to be in the Spanish Sahara, and Cronkite is again relegated to the small screen 4.

“Dissolve the r.p.,” orders the director, and the yellow background and elaborate map follow Bob Schieffer into the limbo of used news.

“This one’s a minute twenty-six.”

Cronkite leans back in his chair and stretches his arms, tells a joke to one of the newsroom writers. In the control room, a call comes over the intercom from the newsroom. “We’re taking the last sentence off Portugal,” directs a voice. “Also the last sentence off Franco.” The director, assistant, and producer all flip quickly through their scripts and note the changes.

The phone rings. “That’ll be Washington,” predicts the producer. The scripts were cut because Fred Graham’s scheduled report from Washington concerning Supreme Court nominees had to be lengthened by twenty seconds. There was interesting late-afternoon footage, it seemed, of Betty Ford urging the appointment of a woman to the High Court.

Rarely does late afternoon footage make the Evening News. It takes several hours to process and edit film for broadcast. Only from a city like Washington, where CBS keeps virtually duplicate equipment linked to New York by permanent cable, can afternoon film be readied in time. Of the six to eight film reports aired nightly on the Evening News, almost a third are a day old or more — Tom Fenton’s desert visitation occurred two days ago — the time it takes to fly raw film to New York for processing and editing. Had his findings been more urgent (for example, instead of peace), Fenton’s report might have merited the price of satellite rental in order to be shown the same evening. The reason Jerusalem was simulated on a map instead of portrayed on film is that to have it otherwise would have cost $8000 in satellite fees, and the Evening News producers didn’t think the story was worth the difference.

The dual restrictions of time and budget are the principal reasons why network news often appears to be overly fascinated with the Eastern Seaboard, especially Washington. Another third of the Evening News’ film reports invariably originates from Washington, and even CBS’ own correspondents — excepting those in Washington, naturally — complain that this is far too much. But besides being in the eastern time zone, Washington’s permanent cable means that footage from there travels “free,” and those are both powerful advantages.

During a working day in the CBS newsroom, the critical point of decision is always whether to “order a line” — to lease a remote cable from AT&T — to bring in a story. Since the largest single expense in the Evening News’ weekly budget (excluding overhead) is the cost of these “remotes,” every producer with an eye on his job will think very cautiously before orodering a line to San Antonio, say, to retrieve film that might not prove useable.

“Ten seconds left,” calls the engineer.

“It’s yours,” answers the director.

Cronkite is watching his monitor as Tom Fenton signs off from the Spanish Sahara. Together with fifteen to twenty million other viewers, he is seeing it for the first time. Unless it’s his own, Cronkite only previews film when a producer or an editor asks him to, and that’s not a very frequent occurrence.

“. . . three, two. . .”

“Take it.”

A jovial man appears on the MASTER screen, apparently talking about gasoline. He is trying to sell it.

Though he likes to think of himself as simply a journalist — “just an old wire-service reporter,” allows Walter, “a pretty good desk-man” — there is clearly more to him than that. One does not command the attention and confidence of a nation with merely efficient desk-work. Without getting mystical about him (“I don’t believe in God,” went to the Jack Paar line, “but I do believe in Walter Cronkite”), I’d suggest that he comes closer to fitting Saint Augustine’s definition of God — as a borderless, ubiquitous Being whose center is everywhere at once — than he does any ordinary notions of a journalist.

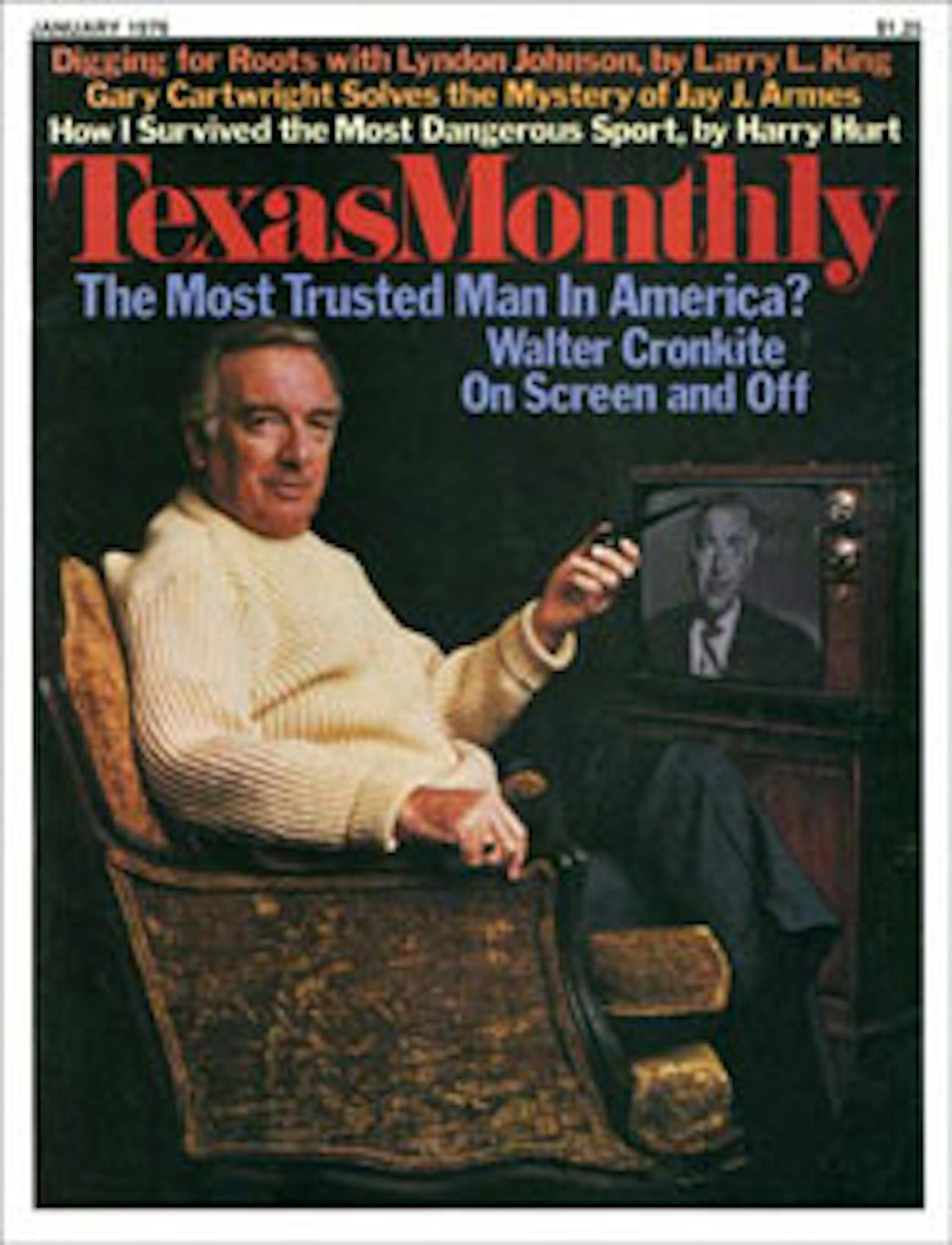

For the better part of the last decade, whenever some pollster has attempted measuring the “trust” or “respect” we bestow on our national leaders, Walter has captured top honors with no exceptions and little trouble. He’s also been rated “the best-liked” figure on television, comfortably ahead of Johnny Carson and four times better-liked than Cher. He’s been called the “definitive centrist American,” the “epitome of the average guy,” our “national security blanket,” the new “father figure to a country in need of one,” and “everybody’s uncle.” A pretty good desk-man? — now, really.

Uncle Walter, then. It’s appropriate, I think, as those Bicentennial ironies loom ever larger, that Uncle Sam’s replacement should be a television figure; the line of succession reflects our altered society. And the truth is, it’s not a bad choice. Who else is there, after all, that we can all trust and respect, even admit a touch of affection for? Afer Viet Nam, Watergate, and the CIA, it sure isn’t Uncle Sam. As Walter puts it himself, while dismissing his “trust-index” championship with predictable self-effacement, “I think it’s just because the threshold of trust is so low these days” — which of course it is, but that’s precisely the point.

By now, Walter must have alighted in billions of living rooms to announce the way it was, and he’s never once been caught as a liar. Never in all those opportunities has he tried to put over a fast one. Why, the very concept of Walter’s lying is preposterous. His whole person seems to radiate sincerity, a kind of innate, Calvinist honesty that can’t be manufactured or affected, and certainly not perverted.

Which isn’t to say that he’s never been wrong — he has — but rather, and far more important, to observe that he’s never avoided the burden of our trust or cheapened the honor of our estimation. If we trust him as we do, it’s perhaps because we sense that he’s trying so hard to live up to it. His occasional lapses from character — those random tears and ecstatic cheers (“Hot-diggity-dog!” was his reaction to Apollo 11’s lunar lift-off) — have allowed us to gauge the depth of his façade, to judge his substance. For all his efforts at ponderous dignity, Walter is simply too transparent to prosper as a con man or a modern politician (if there’s any difference).

He’s also an absolute fanatic about “objectivity,” which he takes to mean telling it straight without preconceptions or personal emotions. Talking to Walter Cronkite about objectivity is akin to discussing salvation with Billy Graham. His breath gets short and his sentences faster, his cheeks heat up and his eyes turn even bluer. He makes it sound like the Holy Grail. No matter that it’s an unattainable ideal: the nature of objective reality has been the prime topic of Western philosophy for the last two centuries, and I can’t honestly say that Walter contributes much to the dialogue. He’s just so damned earnest about it that you have to believe him.

Integrity, in the long run, is more telling than veracity, and harder to come by.

“Roll it.”

“. . . go to Detroit,” Cronkite is saying, “for a report by . . .”

“Roll it!”

The picture on screen 9, of a test pattern surrounding the number 6, does not move.

“Roll, you bastard!”

The tape rolls.

“Well, crap, it got hung up.”

Cronkite is staring solemnly into the camera, having completed his scripted introduction. He sees that the camera’s tiny red cue-light reis still on, and, having scarcely missed a beat, he adds, “. . . on yet another kidnapping.” A four-word ad-lib.

“Hit it,” instructs the director, and the MASTER screen suddenly offers a kidnap story from Detroit.

The delay caused by the hung tape amounted to less than two seconds, easily covered by Cronkite’s brief ad-lib, and undoubtedly it went unnoticed by every viewer in the country. It sufficed, though, as a neat demonstration of smooth professionalism.

Due partly to that professionalism, The CBS Evening News with Walter Cronkite has been America’s top-rated news program ever since June 1967, when it finally surpassed NBC’s Huntley-Brinkley Report after a closely matched four-year ratings war in which NBC held the nominal edge. Cronkite, who was stung by NBC’s constant promotion of its earlier lead, almost never refers to his own current supremacy. “I think people make way too much of ratings,” he mumbles uncomfortably when asked about it.

Generally speaking, however, the people who make the most of those ratings are Cronkite’s employers at CBS, who never cease talking about them — and also, in a sense, Cronkite himself, who’s become the world’s highest-paid newsman (around $300,000 annually, with three months off) as a result of them. In October of last year, the Evening News was shown on approximately 200 stations to an estimated fifteen million people daily, drawing an average Nielsen rating of 13.4 (as compared to NBC’s 13.1 and 9.4 for ABC). Excluding Chet Huntley, who attracted far more than his half of the Huntley-Brinkley audience (a fact NBC belatedly discovered after his retirement), no one in television news has ever approached Cronkite in the ratings.

At the same time, however, the extent to which he’s responsible for his own ratings is open to question. For one thing, the CBS Evening News is carried on more stations, in more markets, than either of its competitors, which means it’s simply available to more viewers. There’s also the phenomenon of “audience-flow”: CBS, until this year dominant in daytime programming, has been able to deliver a far greater portion of already-tuned-in viewers at the outset of the news hour. It’s like following Mark Spitz on a relay team.

And last, but most important, there is CBS’ historical preeminence in broadcast journalism, dating back to Edward R. Murrow’s electrifying dispatches during the Battle of Britain (“This,” whispered Murrow, pausing awesomely as buildings crumpled and bombs rained, “is London”). It was Murrow, probably the greatest journalist of his generation, who recruited one of the finest reportorial stables ever assembled — including a United Press reporter named Cronkite, who’d been something of a war correspondent himself.

From the Forties, when TV news was born, CBS has nearly always spent more money, hired more (and better) people, given them freer (comparative) rein, and taken greater (relative) risks on its news operation than either of the other networks. CBS has gotten most of the credit for the major innovations in TV news (e.g., documentaries, live coverage, stand-up remotes, etc.), and all have been effected by one of two people: Murrow or Cronkite.

This is all on a very relative scale, of course, restricted as it is to a mere three networks. There are serious drawbacks to television news, particularly the scarcity of information it provides, the appalling lack of depth. The entire script of the Evening News, in one famous experiment, covered less than two-thirds of one page from the New York Times. “In too many cases we’re still a headline service,” admits Cronkite, characteristically candid. “We can’t possibly supply the wealth of detail the informed citizen needs to judge government performance. I think most of us will acknowledge that we’re not an adequate substitute for the daily newspaper. I wish people didn’t rely on us so heavily.”

Like most older TV newsman with a background in print journalism, Cronkite has a firm distaste for “show-biz gimmicks and nonsense”—those “happy-talk” formats with breezy, chatty, ever-grinning commentators who swap pale witticisms while they’re on the air. The Evening News, under his tutelage, is strictly a no-nonsense enterprise, devoted, for the most part, to presenting the unembellished news as simply and straightforwardly as 27 minutes will allow. “I think you should just tell it the way it is,” he says.

“And that’s the way it is,” says Cronkite.

“Cut it,” says the director.”

Visitors to the CBS Broadcast Center, a converted dairy known to its denizens as “the cowbarn,” are greeted not by a receptionist but by a brusque guard. They are required to sign in at the desk and wait for an employee, usually a hastily summoned secretary, to escort them into the maze of corridors to their destination; and then back again; or from office to office; wherever visitors go, it is always with an escort. Surveillance is continuous: even the streets outside are monitored by closed-circuit TV cameras.

Many of the corridors weave through the west wing of the second floor connecting the offices of the 800 employees of CBS News, a division of the CBS Broadcast Group, which is a subsidiary of CBS Inc. This largest entity, however, involving such diverse endeavors as Bob Dylan and Pentagon contracting, is headquartered across town in a monolith aptly referred to as “Black Rock.” One of the corridors at CBS News empties into the room housing the 35-member staff of the Evening News.

A small sign on the door discreetly proclaims THE WALTER CRONKITE NEWSROOM: a warren of cramped, fiberboard cubicles encircling a messy plateau of disarrayed, mismatched desks. From somewhere to the left comes the frantic rattle of Teletype machines; strewn over everything are the files, folders, books, newspapers, press releases, bureau reports, reams of yellow wire copy—all the daily flotsam that conspires to form “the news.” Except for the thick tangle of lights and wires descending from the ceiling, it could easily pass for the city room of a big metropolitan daily. There is even the harried ambience, the inspired, semi-organized, shirt-sleeved bustle of the city room. It does not feel at all like a television studio.

By midmorning, everyone has dutifully scrutinized the New York Times and the wire-service “daybooks”—voluminous calendars of scheduled events, press conferences, meetings, debates, and appearances. Drawing on these two sources for the majority of their suggestions, the producers and editors have made their assignment decisions and issued “blue sheets,” the assignment forms that, barring conflict with another CBS News department (the Morning News, say, or Documentaries), denote an exclusive for the Evening News.

Their judgments are based upon the weighing of two factors, the potential news value of the story and the ease with which it can be delivered—a factor encompassing time and budget questions, the availability of correspondents, the whereabouts of camera crews (the Evening News can utilize one of twenty-plus crews belonging to CBS News), and the personal predilections of the judgment-makers. The remainder of the day, then, will be devoted to executing the decisions of the morning.

Just before 1 p.m., Evening News executive producer Burton Benjamin and his two senior producers, Ron Bonn and John Lane, will go to lunch together. From their meeting will emerge the tentative lineup, the roster of stories most likely to appear during the show’s twenty-four minutes (the twenty-seven minutes of the Evening News minus three minutes for Eric Sevareid’s impenetrable colloquy). Actually, they are really dealing with between fifteen and eighteen minutes, since the rest is given over to Walter Cronkite’s summation of those lesser occurrences that couldn’t merit film reports.

The total time to be consumed by Cronkite is known at CBS as “the magic number.” The producers have fifteen or sixteen minutes left, and the entire worldwide apparatus of CBS News is concentrated every day on filling this time, on fighting for shares of it, on making it greater; holding it down is the weighty presence of Walter Cronkite, the putative managing editor of the CBS Evening News.

The managing editor’s office is tucked in a corner and partitioned with glass, the standard arrangement for managing editor’s offices. Efficiently small, it contains a cluttered desk, a couch too short to lie down on, two walls lined with nonfiction books, and an odd assortment of rocket models, spaceship models, race car models, sailboat pictures and minor personal mementos; all exactly as it should be. Cronkite is behind the desk holding a clip from the morning’s New York Times and conferring with a staff member. Seeing him through the glass reminds me that I still haven’t figured out how to launch my interview.

Those first questions often decide the tone and course of a whole interview, so they naturally form a crucial element in one’s “interview strategy”—a wishful design similar to the game plan of a football coach. I’d spent three weeks preparing for this one: studying previous interviews, sketching out topics, refining notes, plotting strategy; and now, eavesdropping from the doorway, I was at a dead loss for where to begin.

It wasn’t that I didn’t have questions; I had two weeks’ worth of questions and was only scheduled for half an hour. The problem was I didn’t have any openers. You can’t jump right in and ask a man if he’s really an air-hog. Not even Mike Wallace would do that, and Mike Wallace is the meanest interviewer since Cotton Mather. An interview is something you slip into gingerly, like a canoe: you don’t push off until everyone’s settled in.

Cronkite, for instance, is a master of the slowly launched interview—some of his interviews never seem to escape the shoreline. He’s frequently been criticized as a “marshmallow” interviewer, as too soft and easy-going; it’s the single widespread criticism there is of him. Sensitive to the charge, he gets quite testy if you ask him about it. “I don’t believe in these headline-hunting interviews,” he growls. “That’s just not my style.” Period.

His “style,” such as it is, is basically a mixture of old-fashioned wire-service and down-home Good Ole Boy: rambling, discursive, spontaneous, more like Johnny Carson than Mike Wallace. It’s genial and deceptive, and it can even be effective. By relaxing and drawing out his subjects, he sometimes gets them to reveal more of themselves though expression and nuance; they may occasionally, if sufficiently disarmed, say something really foolish. In the classic wire-service model, the reporter scribbles dozens of pages of notes and reviews them later to see if anything was useful. In the Cronkite television variation, he gets hours and hours of loquacious film, then edits it down to whatever was interesting.

Another consideration here is that Walter Cronkite simply isn’t nasty enough to be a very aggressive interviewer. During his lengthy, three-part Lyndon Johnson interview, billed as “a memoir,” Johnson still (this was after LBJ’s retirement) resolutely maintained that landing the Marines at Da Nang was one of the great moments of Christendom, and it was obvious that Cronkite was frankly astonished. He gently pushed the subject a little harder, without success, but he just didn’t have it in him to get tough, to tell Johnson flat-out that he was misstating the facts, as indeed he was. What Cronkite did instead was insert film clips into the broadcast interview that presented the rebuttal that he couldn’t bring himself to make in person.

And besides that, talking to Mike Wallace probably isn’t as pleasant as talking to Walter Cronkite. Which, by the way, I had finally begun to do. I’d produced an opening question that seemed relaxed, sensible, certain to get us off on the right track.

“Have you ever been to Beirut?” I ask him.

The question did not seem as ridiculous at time as it does looking back on it.

The Times clip he’d been holding concerned the fighting in Lebanon, and Cronkite was instructing the staff member that he wanted a map of Beirut drawn up to accompany his report. He went on and on about the various details to be included in the map. “I don’t know where the Chiyah section is, but obviously it’s a Moslem section,” he had said. “So that should be in there. And the American University. I don’t care if this Kantari Street is on it or not, but I just want to know where it is…”

So we talked about Beirut for the first half of my scheduled 30 minutes (he’d been there twice).

The thing you need to know, in case you’re ever called upon to interview Walter Cronkite (nobody ever told me), is this: he loves to talk. The man is a born talker, an old-school yarn spinner who’ll put his feet up on the desk and turn loose of some marvelous stories. He had a couple of fascinating Beirut yarns.

As for me, well, I couldn’t get over the fact that Walter Cronkite didn’t have a screen around him. I didn’t take a note.

Outside of the missing screen, he doesn’t look a lot different in three dimensions that he does in two. A little heavier, perhaps (there’s an extra chin or so that you don’t notice on television), and his nose seemed awfully red, but I’m told it was just because he had a cold that day. He was wearing a monogrammed Givenchy shirt, a fairly boisterous tie (one of his weaknesses) and the onyx ring his parents gave him for graduation from Houston’s San Jacinto High School in 1933.

After finishing off Beirut, we started discussing his penchant for visual aids, like maps and charts, which is one of the things that sets Cronkite apart as a TV newsman. Conventional television wisdom decrees that such static devices are sure death, guaranteed to drive viewers to rabid fits of channel-spinning. They are the antithesis of show biz. Cronkite, however, employs them at the drop of a hat and with amazing success. One of his landmark newscasts was a special report on the first Russian Wheat Deal, which saw him go to a blackboard and start drawing diagrams like a small-town algebra teacher. For twenty minutes he lectured until the whole convoluted grain hustle had been clarified, or at least illustrated, right there on his silly blackboard. It was terrible television and first-class journalism, and nobody but Cronkite could ever have pulled it off.

“Maybe I’m just a slow learner or something,” he says, referring to his charts, “but I like to have things laid out as plainly and simply as possible. I’m not sure people absorb rapid, newspaperese style, not on something as complicated as the Wheat Deal. I don’t think we do enough of it.”

He had the same simplifying approach to his prose. More than any other TV newsman’s, Cronkite’s scripts have the ring of the wire-service dispatch, the spare, unadorned message of “the facts.” He takes pride in their leanness (“I’m one of the best condensers in the business”), and he’s careful to tend to them himself. Oddly enough for a man who’s spent 25 years on television, he will introduce film that he’s never seen beforehand, but he won’t handle a sentence that he hasn’t tooled himself. In his heart he’s still a word-man.

Beginning in the afternoon, as stories are booked into the lineup and “the facts” made available, Cronkite will confer with the Evening News’ four writers to develop a script. It will constitute his major work of the day.

In theory, Cronkite is merely one of the 35 underlings laboring for executive producer Benjamin (who in turn labors for news director Bill Small, who in turn is responsible to an endless chain of bureaucrats leading into the corporate maze of Black Rock); but in practice Cronkite is the ultimate power in the Evenings News, the man known throughout the building and without noticeable affection as “The Star.” Regardless of titular corporate authority, his is the decisive judgment in shaping the Evening News.

On a continuing daily basis, though, he rarely exercises his prerogatives, except in fashioning his own six- or seven-minute scripts. “I know I’m fast and accurate,” he says of scripting skills. “I’m kind of egotistical about my news-editing ability.”

From here, the interview drifted naturally to the larger topic of journalism. I’d planned on avoiding this, actually, both because its hopelessly predictable and because every other Cronkite interview I’d come across dwelt painfully overlong on it, and I doubted he would tell me anything he hadn’t said elsewhere, many times over. But as I say, we drifted…

“I think the excitement of being in on everything,” he muses, “is what attracted me to it. When I was a kid reporter in Houston I used to think life just wasn’t worth living if I couldn’t be in on the action.”

There’s no mistaking his commitment. You can criticize Cronkite as a journalist—his premise, his performance, those marshmallow interviews—but you cannot argue his devotion to journalism. He’s a man who decided at age twelve that he wanted to be a reporter, and for close to 50 years now he’s faithfully marched to that curious bystander’s drum. During that time he’s amassed enormous potential power, yet he’s spent all his life trying to deserve it rather than use it.

With few exceptions, in fact, the only times he’s actively sought to influence public policy or opinion have been in behalf of his profession. Whenever the Fourth Estate has come under attack, Cronkite is usually among the first to the barricades. He’s fought with four presidents, including Eisenhower—the one he was closest to—over various incursions upon freedoms of the press; and when John Mitchell’s Justice Department began willy-nilly seeking reporters to subpoena in 1969, Cronkite privately declared his intention to go to jail before answering any—a thought which no doubt mortified John Mitchell almost as much as it did CBS.

“It’s ultimately the most important freedom we’ve got,” he observes, waxing pedantic. “Press freedom is what makes our other freedoms possible. We need to be jealous of it, we need to be vigilant.” He enjoys talking about journalism: those soft, empathetic eyes brighten several watts as he warms to the subject. He’s said it all endless times before, probably, but still he’s interested, into it, his rhetoric freights real emotion. “I don’t think there’s ever been a president, Republican or Democrat, who thought he was being covered the way he should be. I’d start worrying about our coverage if they like everything we said about them. An adversary relationship is the only kind we can have with government.”

Fred Friendly, one of the pioneers of television documentaries and a former president of CBS News, once remarked that “Walter’s a success because he cares so deeply for the news,” an observation Cronkite readily accepts.

“Once you begin broadcasting a story the old adrenaline starts flowing,” observes Cronkite. “I just love working with the news, the way farmers love working in the black dirt of Iowa, for example.” When Cronkite refers to “the news,” he means “hard news,” the daily contribution to the historical record. Cronkite’s enthusiasm for (or fealty to) hard, objective facts has caused him to reject the numerous urging of CBS that he enter the “pontificating racket,” as one newsman referred to the business of interpreting the news.

“I think I could blast the hell out of an issue,” says Cronkite, “and it wouldn’t affect my objectivity in presenting both sides to it; but I think it would hurt my credibility with the public. They wouldn’t understand that I could still be unbiased and objective.”

There is something troublesome about this view of news, this total commitment to objectivity. Taken to its extreme, objectivity is little different from impassivity; it becomes nothing more than indiscriminate transmission of facts without regard to the original context that made them seem important in the first place.

The news comes to be viewed as just so much unrelated data rendered similar and significant simply by being chosen to appear on the News. The result is that the journalist who weds himself to total objectivity is easy prey for managed news like the Gulf of Tonkin Incident, the source of presidential power to intervene at will in Viet Nam. It became one of the most significant news stories of our time, despite the fact that it was cut from whole cloth in the Pentagon and never really happened.

Still, Cronkite insists on a strict concept of the reporter’s role. “Our responsibility is just to report the facts and let the public weigh their importance,” he says.

It occurs to me, somewhere along in here that I have overstayed my allotted 30 minutes. Nobody seemed to mind, though, so we talked about Houston for a while, about the abortive deal he was involved in, albeit peripherally, to buy the Houston Chronicle in the late Sixties (“Could be a great newspaper,” he says, “shame it’s not”). He recalled the days when he and Stuart Long, now the dean of the Austin press corps, were part-time reporters in the Texas Legislature (“We were the two most eager guys around the Capitol, there was nobody who could keep up with us”), or covering Lyndon Johnson’s maiden congressional race in 1937, when Johnson was the farthest left of a seven-man field (“That fact always colored my evaluation of him; years later when a lot of people were calling him a Southern conservative, I remembered that race”).

I began to realize, about this point that my interview has degenerated into a conversation and me into a marshmallow. It’s unavoidable. Cronkite emits this infectious, exuberant sort of friendliness that tends to compel conversation. Fascinating strategy, I say to myself, and revolve to ask at least some of my original questions.

“Is there any truth to the rumor that you might retire in Austin and teach journalism at the University of Texas?”

“Ohhh,” smiles Cronkite, “I don’t know, it’s a possibility. I hope so.” He slides off the question with dexterous ambivalence, but graciously, and I don’t press it. But I do know he returns to the campus for occasional visits or business. Once he wandered through the University area looking for his old Chi Phi fraternity house. In 1970 he attended a pep rally before the Arkansas game and called hogs to help bait the Razorbacks. A man doesn’t get up and call hogs in front of 30,000 people unless he owns considerable affection for his alma mater.

Or else he’s just naturally mischievous and impulsive, which is Cronkite too. He’s forever turning up at policemen’s balls, neighborhood saloons, senior proms, walking his dime-store turtle around East 84th Street. An inveterate dancer, with a reputation as the fastest floor-man since Caesar Romero, he’s been known to entertain friends with a makeshift striptease, and his wife Betsy once referred to him as a “thwarted cruise director.” It’s no wonder that he seems so comfortable in your living room; he is comfortable in your living room.

Indeed, if Cronkite holds by any ideology at all, it is that of an optimist and a romantic. He confesses to have liked almost every politician he’s ever met, hates to get presents that are passably practical, and once described himself as a “frustrated song-and-dance man.” Or, another time: “I’d like nothing better than to be an Irish bar drunk, making friends with everybody.”

He took up sports car racing in the Fifties when he found himself one day, quite by accident, in a used-car lot with a check in his pocket for a lecture fee. He left driving an Austin Healey, later traded up to a fully bored Lancia, and pursued serious racing until he went off a 110-foot cliff in a road rally though the Great Smoky Mountains.

That’s when he took up sailing, shortly after finding himself, quite by accident again, at the New York Boat Show with another check in his pocket. “I’ll take that one,” he announced to a startled salesman, and he became a sailor. A fanatical sailor. He devours sea novels and windjammer sagas, loves sailboat lore, yacht clubs, and naval history; and his ultimate ambition is to circumnavigate the globe in a three-masted schooner. “Boy,” he sighs dreamily, “wouldn’t that be great. Just putting in wherever you felt like, staying as long as you wanted. I’d love to do it.”

Meanwhile, I press on with the interview. Not dismayed by a mere fielding error on my first question, I toss out the meanest question in my notebook (Mike Wallace would’ve been pleased): “Why do some people accuse you of being an air-hog?”

He scowls somewhat, looks into his lap. “I don’t think so,” he says slowly. “When we made the jump to a half-hour, I was the first one to allow stand-ups from the field correspondents. Hell, I encouraged using them. I didn’t see why I should sit up here and talk about something when we had people there on the spot who could see it..”

To an extent, the charge of air-hogging is a symptom of intramural jealousy in an organization where everyone wants to get on the air. It’s the whole point of television, after all. Within CBS News though, there is as much hostility toward the Washington bureau as toward Cronkite when it comes to hogging the Evening News.

The complaints about Cronkite are mainly promoted by special events coverage, such as political conventions, when correspondents have been known to snipe at CBS’ “Walter-to-Walter” format. And there is some truth to the complaint—but also rationale.

“The time he is best,” said a former CBS producer, “is when he’s been on camera so long he’s too tired to be anything except himself.” Even more than as an anchorman, Cronkite’s reputation and career have been formed in the garrulous course of his marathon broadcasts—some as long as seventeen consecutive hours, the television record he set during the 1968 election returns.

“He has the ability,” said one TV critic, “to extemporize smoothly and almost endlessly.” It is here, in the realm of live coverage—conventions, space missions, elections, A-bomb tests, national emergencies, whatever and wherever—that Cronkite has truly made his mark on broadcast journalism. Through all the manner of crisis or occasion, he has held his ground for hours on end, providing, depending on the situation, either cogent and reasoned reporting or epic-length ad-libs. As was pointed out earlier, he loves to talk.

“The more I’m on, the cooler I become,” he says. “The only time I feel nervous is when I’m unprepared, when I haven’t done enough research.” Which, judging from the record, is seldom. Cronkite is a prodigious researcher, a man who prepared for his spaceflight coverage by reading every manual available, tasting weightlessness in parabolic flight, hurtling though a centrifuge, visiting every tracking station from Florida to Ascension Island.

On the subject of marathons, I was suddenly aware that my interview had dragged on far longer than it was supposed to. I also noticed a small line had formed outside of the managing editor’s office: staff member seeking advice, assistance, or simply information. Cronkite’s role in the decision-making process for the Evening News is fairly sporadic, mostly by his own choice and depending on his interest in specific stories, but his stature is such that newly every decision is checked for his approval.

Endeavoring to slip in a last query, I flip quickly though my four pages of unasked questions and randomly select one: “Is it true,” I blurt, “that you once drank beer with Clyde Barrow?”

His grin dissolves as he stares back at me. “How did you know about that?” he demands.

“Uhmm,” I say, not remembering. Oh my God, I think to myself, he’s been a closet bank robber all these years, with Bonnie and Clyde!

“That’s one of the stories I’ve been saving for my own book,” he alibies, “I didn’t think anybody knew about it.” He sinks back into his chair and reestablishes his feet on the desk.

His book, eh. Well, that’s plausible, I think. I tell him I can’t remember where I came across the tip.

“I’ve only got four or five stories nobody knows about,” he says, looking a little hurt. “I’m not going to have any left for my book.”

Naturally enough, I decided to believe him. Reflex action, probably. But now I’m looking hurt for not getting to hear the story, and he’s looking wistfully into his hand. He smiles a little, thinking about his adventure.

“I’ll tell you what,” he says, grinning again. He wants to tell the story almost as much as I want to hear it. “I’ll tell you the story if you promise you won’t use it.”

“Oh sure,” I say, totally without scruples.

He looks me directly in the eye. “Are you sure you promise?”

We’re like twelve-year-olds.

“Oh, I promise, I promise.” As I say, no scruples at all.

So then he gazes off toward the ceiling and tells me about drinking beer with Clyde Barrow. It’s a good story, and, like most of his stories, he relishes telling it.

I wish I could pass it on, but I’m sure you understand the problem.. I mean, when the officially certified most trusted man alive trusts you, what else can you do?

The Other Texas Anchormen

In Sally Quinn’s book We’re Gonna Make You A Star, which is about CBS’ foolish and foredoomed effort to do just that with her, she isn’t very nice to most of her erstwhile colleagues. The one she is nicest to of all, however, is Hughes Rudd, who was briefly her co-host on The CBS Morning News, a program launched with great fanfare about two and a half years ago to compete against NBC’s Today Show.

The Today Show’s ratings, of course, have been untouchable ever since Dave Garroway inaugurated the show in 1951. In an earlier challenge, in 1954, CBS went up against Garroway with their hottest new star, the man who won national acclaim for his coverage of the 1952 political conventions (the first to be broadcast live), Walter Cronkite. But Cronkite didn’t like being a “personality” instead of a reporter, nor did he like the gag-writer they hired for him, so he was yanked in a few short months and replaced with Jack Parr.

Sally Quinn lasted about as long as Cronkite. She did, however, get a very funny, very catty book out of experience, in which she portrays Hughes Rudd as a warm, wise, sympathetic man and the closest thing to a hero in the book. During some short-lived discussions aimed at making the book into a movie, the one point that was unanimously agreed upon was that Walter Matthau should play Rudd. Walter Matthau, you should know, would be perfect as Hughes Rudd.

Born and raised in Waco, Rudd was a United Press reporter until Cronkite recruited him for CBS in 1959. He opened their Southern bureau for them, was posted to Moscow, Europe, and Viet Nam, and somewhere found time to publish a collection of first-rate stories and essays, My Escape from the CIA and Other Improbable Adventures.

“Back then you were really on your own,” he says, recalling his early days at CBS. “You told New York what you were gonna do. You didn’t have to go running all over hell because somebody in New York got up in the morning with a bright idea. You didn’t have any of this nonsense with ‘bureau managers.’ You just had a reporter—in this racket they call ‘em ‘correspondents’—and a camera crew. It was a lot simpler then and it was at least as good; maybe better.”

His cynicism is coated with a wry wit and embroidered with fascinating anecdotes, and thus emerges as a kind of earthy, affable satisfaction. He is a very mellow man. He is also a fabulous raconteur, as good as Cronkite with a little more salt, and his ad-libbing talents have begun to pay dividends at The Morning News. When they debuted in 1973, NBC held a four-to-one ratings edge which has steadily narrowed to 29 “shares” for Today against 25 for The Morning News.

Two other Texans also hold down CBS anchor slots. Bob Schieffer (Fort Worth) as recently been appointed anchorman on the Sunday night CBS news; Richard Nixon’s old adversary Dan Rather (Wharton) is co-anchorman on 60 Minutes and also presides over special CBS Reports programs like the recent two-part series on the Kennedy assassination.