“Dark Was the Night—Cold Was the Ground”

On August 20, 1977, NASA launched the Voyager 2 spaceship on a one-way ticket to oblivion. Three weeks later, its sister craft, Voyager 1, blasted off with the same destination. Their mission for the first dozen years or so, as they cruised through the solar system, was to gather data from the planets. Their goal for the next 60,000 years or so, as they leave us far behind, is to carry a message in a bottle to the stars. Alongside an array of high-tech cameras, infrared instruments, and a large parabolic radio antenna, each Voyager bears a stylus, a phonograph record, and directions for playing it. The record isn’t Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours or Kiss’s Love Gun, both of which were top ten albums in the summer of 1977. This record is made of copper and plated in gold, created to last forever, to offer an audio and visual slide show of all things Earthly. This is who we are, it says. Or were. The record includes words (greetings in 55 languages), sounds (a train, a kiss, a barking dog), pictures (mountains, dolphins, sprinters), and ninety minutes of music. There are panpipes from Peru, bagpipes from Bulgaria, and drums from Senegal.

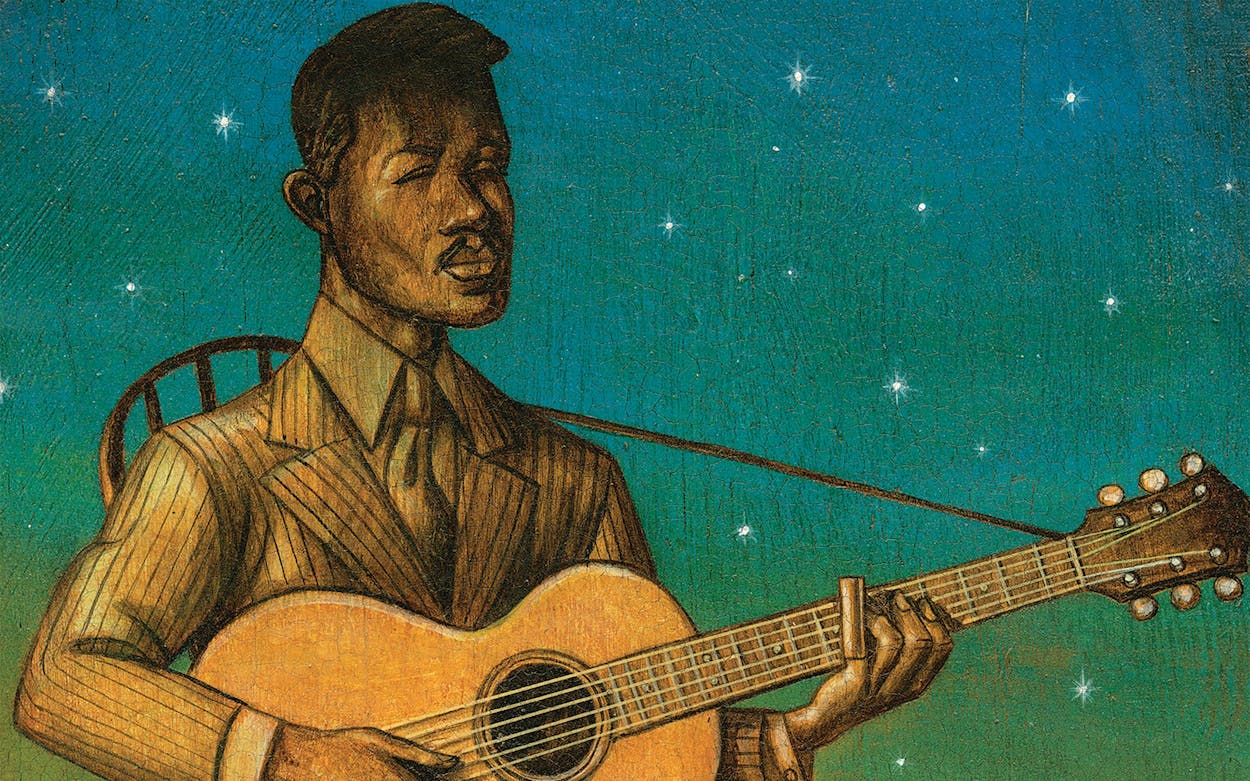

And at the very end, summing up the power and the pathos of everything that went before, are two singular pieces of music by two singular men who couldn’t have been more different. One was a deaf German whose song was recorded by a string quartet in a professional studio. The other was a blind Texan who played his song on a cheap guitar in a Dallas hotel room. The German is Ludwig van Beethoven, and he closes the album, befitting his reputation as the greatest composer ever. The Cavatina from his thirteenth string quartet was written in his last years, when he was dying. It is six and a half minutes of sweet elegy, music that says what couldn’t be put into words. This is it. This is the end.

Leading into it is a song recorded and played by a twentieth-century street musician, Blind Willie Johnson. The song is “Dark Was the Night—Cold Was the Ground,” a largely wordless hymn built around the yearning cries of Johnson’s slide guitar and the moans and melodies of his voice. The two musical elements track each other, finishing each other’s phrases; Johnson hums fragments of the diffuse melody, then answers with the fluttering sighs of steel or glass moving over the strings. Sometimes the guitar jimmies a low, ascending melody that sounds like a man trying to climb out of a mud hole. Then the guitar goes up high, playing an inquisitive, hopeful line, and the voice goes high too, copying the melody. There’s no meter or rhythm. In fact, “Dark Was the Night” sounds less like a song than a scene—the Passion of Jesus, his suffering on the cross, the ultimate pairing of despair and belief. The original melody and lyrics (“Dark was the night and cold was the ground, on which the Lord was laid”) may have originated in eighteenth-century England, but Johnson reinvented them. Occasionally his slide clicks against the neck of the guitar, and you remember that this was just a man playing a song in front of a microphone. You can hear the air in the room. You can hear the longing in his voice. This is what it sounds like to be a human being.

The slide guitarist and producer Ry Cooder, who used “Dark Was the Night” as the motif for his melancholy sound track to Paris, Texas, once called the song “the most transcendent piece in all American music.” In about 60,000 years, one of the Voyagers just might enter another solar system. Maybe it will be intercepted. Maybe the interceptors will figure out how to play that record. Maybe they’ll hear “Dark Was the Night.” Maybe they’ll wonder, What kind of creature made that music?

“I Know His Blood Can Make Me Whole”

There are hundreds of books on Beethoven; though he was born 240 years ago, we know almost everything there is to know about him. But Johnson is an utter mystery. We know that he died on September 18, 1945, in Beaumont. But we don’t know for certain when and where he was born, and it’s possible we never will. Almost everyone who knew him is gone. And though a few of his contemporaries told stories about him before passing on, many of them had lively imaginations.

What we know for sure is that for a brief period of time, Johnson was a recording star, one of the most popular gospel “race” artists of his era, outselling the renowned blues singer Bessie Smith during the Depression. He recorded thirty songs between 1927 and 1930; many featured a female background singer. His first two sessions were in Dallas, in 1927 and 1928, and he recorded many of his best songs there—“Dark Was the Night,” “If I Had My Way I’d Tear the Building Down,” “Mother’s Children Have a Hard Time.” His first song, “I Know His Blood Can Make Me Whole,” was released in January 1928 and sold 15,400 copies, a lot for the time. He received attention in unusual places. Johnson was “apparently a religious fanatic,” wrote one critic for the New York literary review The Bookman, who also noted his “violent, tortured and abysmal shouts and groans and his inspired guitar.” Johnson’s third session took place in New Orleans in 1929, and his last was in Atlanta in April 1930. Only 800 copies of that final record were even pressed. He never recorded again.

And then Johnson disappeared. His style of guitar playing lived on through the thirties and forties, as musicians like Robert Johnson, Muddy Waters, and Mance Lipscomb listened to those records and copied his slide technique. Others couldn’t get the sound of those songs and that voice out of their heads. They were driven to find more, to solve the mystery of the man whose affliction had become part of his very name. So they hit the road, drawn to the small towns they thought he had lived in, the ruins of homes he may have slept in, the run-down cemeteries he may have been buried in. They pieced together fact and fiction, and the more they found, the more mysterious he became.

The more researchers found out about Blind Willie Johnson, the more mysterious he became.

The first to seek Johnson was Samuel Charters. In 1948 Charters was a teenager in Berkeley, California, playing clarinet in a Dixieland band. After rehearsals, he and his bandmates would sit around and listen to a mysterious 78 rpm record that they knew nothing about except for the title of the song and the name of the artist: “Dark Was the Night—Cold Was the Ground,” Blind Willie Johnson. It sounded like it came from another world. Sixty-two years later, Charters still remembers that sound, that feeling. It was, he told me, “a shattering experience. It changed my life.”

In 1953 Charters settled into New Orleans with a big tape recorder and dreams of recording blues and folk artists. The one he really wanted to find was Johnson. Soon he came across a blind street singer named Dave Ross who played some of Johnson’s songs. Ross told Charters that he had met Johnson in Beaumont in 1929 and again later that year in New Orleans, when Johnson had come to the city to record. Ross said he thought Johnson was living in Dallas. So Charters and his wife at the time, Mary, were off, pounding the streets of that city’s black neighborhoods. The director of a Lighthouse for the Blind just outside Dallas had heard of Johnson and said there was a blind preacher named Adam Booker in Brenham who might know him.

The couple drove southeast and on November 6, 1955, found Booker in a small cabin on the outskirts of Brenham. Booker told Charters that he had led a church in Hearne in 1925 and that Willie’s father, George, had been a member. Willie lived in Marlin then, but he would visit his father in Hearne and play on the streets on Saturday afternoons, when the cotton farmers and their families would come to town to socialize and buy provisions. “He’d get on the street and sing and pick the guitar and they would listen and would give him money,” remembered Booker. “Every Saturday, he wouldn’t hardly miss.” Booker said Johnson had a tin cup tied to the neck of his guitar with some wire. He also remembered days when Johnson would be on one corner and the great bluesman Blind Lemon Jefferson would be on another.

This whole scenario fascinated Charters. He was traveling through the heartland of some of the great Texas bluesmen—Jefferson was from nearby Coutchman, Lipscomb was from Navasota, and Lightnin’ Hopkins was from Centerville. But Charters knew that, unlike these men, Johnson was a gospel singer, not a bluesman. He sang old spirituals and hymns and occasionally a topical, or “message,” song. His songs were about the love of Jesus and the hope of salvation but also the wrath of God; Johnson believed in the fire and brimstone. He sang in two voices—one clear and high, the other deep and raspy, a voice that a lot of street singers and preachers used to get attention and rise above the din.

Booker said he’d met Johnson again, in Dallas, in 1928, and that he later moved to Waco; he thought Johnson was living in Beaumont. Two days later Charters was there too, walking along Forsythe Street in the black section of town, asking residents if they knew of a blind gospel singer. “Which one?” was the reply. An elderly man, a guitarist. Again: “Which one?” Eventually he met people who remembered Johnson as “a tall, heavy man, not dark in color; a dignified man and a magnificent singer.” Finally a druggist sent him to a shack on the south side of town, where he met a woman in her mid-fifties who said her name was Angeline Johnson. Yes, she knew Blind Willie Johnson, she said. She had been married to him.

Angeline was, Charters later wrote, a nurse and a midwife who was “worn down from too many hard years—a stocky woman wearing glasses, in an old plain dress and sagging apron, her hair tucked under a net.” Charters interviewed Angeline in her neighbor’s house, because she had no electricity. “At first, she was so withdrawn and watchful,” he told me. “But when she realized I really wanted to learn about Willie and their years together in Beaumont, she blossomed.” Warmed by a nearby kerosene heater, Angeline told Charters about the first time she had heard Johnson. It was on the streets of Dallas, on June 21, 1927, and she had sung along with him on “If I Had My Way.” She invited him to her house, where she played piano and sang with him, then cooked some gumbo. He proposed, and they were married the very next day.

Angeline was the first person Charters had encountered who knew anything important about Johnson. She told him many details, which she said had come from Willie’s father, George, whom she had met. Willie, she said, had been born outside Temple around 1902 or 1903, but his mother died soon after and they moved to Marlin. When Willie was seven, after his father had remarried, George caught his new wife in the arms of another man and beat her. Her retaliation was horrifying. “She throwed lye water in Willie’s face and put his eyes out.”

Angeline sang “Dark Was the Night” and several other songs for Charters in a high, thin, warbly voice. She said that throughout the thirties the couple had moved around a lot—Dallas, Waco, Temple, and finally Beaumont. He lived out his last fifteen years playing on vibrant Forsythe Street (“He loved to play on the streets”) and at churches, including the nearby Mount Olive Baptist Church. He died in 1949, she said, of pneumonia after their house, at 1440 Forrest Street, caught fire. Once the firemen had extinguished the blaze, she had covered their drenched bed in newspapers. “We didn’t get wet, but just the dampness, you know, and then he’s singing and his veins opened and everything, and it just made him sick.” She tried to take him to the hospital. “They wouldn’t accept him. He’d have been living today if they’d accepted him. ’Cause he’s blind. Blind folks has a hard time—he can’t get in the hospital.”

Charters kept searching and found the only known photo of Johnson in a Harlem microfilm archive. “I was so nervous my hands kept slipping on the knob as I went through page after page,” he told me. “Then there he was. I couldn’t breathe for a minute—I just sat staring at the screen.” He wrote up his search for Johnson and his discovery of Angeline in several articles and the 1959 book The Country Blues, which would become a bible of the sixties folk revival. And so was born the legend of Blind Willie Johnson.

But how much of it was true? Charters’s enthusiasm and inexperience led him to make a few mistakes. For example, he assumed that Angeline had sung on the records—and then wrote this as fact. “I thought she must have been with him,” he told me. “But I think I was just wishing she’d been on the recordings.” He also left unanswered several questions that have fueled the obsession of the people who have followed in his footsteps. Where was the rest of Johnson’s family? Why would a hospital turn away a sick blind man? And where was he buried?

“If I Had My Way I’d Tear the Building Down”

By the sixties, Johnson had become a hero to folkies and rockers alike. His “John the Revelator” appeared on the American Anthology of Folk Music, which was the how-to guide for sixties folk musicians; Bob Dylan recorded “Jesus Make Up My Dyin’ Bed” on his 1962 debut (as “In My Time of Dyin’ ”). But Johnson’s real influence was on guitarists such as Eric Clapton and Led Zeppelin’s Jimmy Page, who sat down with his records and copied his every move. Slide playing is not like typical guitar playing, where you press your fingers on frets that measure the pitch of the string exactly. You’re sliding some kind of object—usually a steel or glass cylinder—up or down the strings until you get the right note, which if you don’t hit exactly, will sound sharp or flat. So you slide the cylinder back and forth real quick, creating a vibrato effect. A well-played slide can resemble a person crying, moaning, or even laughing.

Especially in the hands of Johnson. “He’s the very best,” says Steve James, an Austin slide guitarist who spends much of his time touring the world and giving workshops. James has been studying Johnson’s music since he was a boy, in the sixties. “A friend of mine and I were listening to one of his recordings, and we stayed up all night, slowed down the turntable, played it over and over. We figured out he got twelve separate pitches by striking the string once, all inside one measure. I’ve been trying to do that for twenty-five years, and I can do seven or eight. There’s a saying guitarists have when we try to play Blind Willie: ‘I’m getting as close as I can.’ ”

Johnson mostly played in an open D tuning, which means three of the strings were in D, two in A, and one in F sharp, so he could bang a relentless rhythm on the low strings, then accompany it with a melody on the high ones—and then repeat it on the low ones. In some songs he sounds like a one-man band: rhythm section, vocals, slide guitar. No one knows for sure what Johnson slid on the strings. Many players broke off the top of a bottle and smoothed the glass—hence the term “bottleneck slide.” In that famous photo of Johnson, his left hand is holding the neck of the guitar while his pinkie seems to be poking straight out—as it would if it couldn’t bend at the knuckle because of a glass or steel tube.

In the photo, he’s handsome and well-dressed, wearing a coat and tie, sitting upright on a piano bench. He doesn’t look like one of those down and dirty bluesmen. And yet he was their mentor, the guy they all learned from. Every note ever played with a slide—from Robert Johnson to Jack White, of the White Stripes—goes back to Blind Willie Johnson, says James. “He’s an insoluble mystery. How did somebody from the middle of nowhere—blind as a bat—learn to do that? And why?”

It wasn’t just musicians who were drawn to the mystery. In 1976 a Southern Methodist University college kid and blues fan named Dan Williams began looking for Johnson’s ghost. Williams had read Charters’s book and owned a few of Johnson’s records, which he’d found rummaging through thrift stores around his hometown of Waco. “Every time I went into a junk shop in Central Texas,” he told me, “I’d find a worn-out copy of ‘Mother’s Children.’ It seemed like everyone owned one. Seeing those records made him seem real to me.” So Williams began making special trips to Marlin to look for 78’s and to see if anyone knew anything about Johnson. He didn’t have much luck until his third visit, when he walked up to some elderly black men sitting on a bench in the town square. One said he knew where to find Johnson’s ex-wife. An excited Williams thought he was going to meet Angeline Johnson.

Instead, he was introduced to a woman named Willie B. Harris, who said rather nonchalantly that it was she who had sung on Johnson’s records. Williams was skeptical—until he pulled out a 78 of “Church, I’m Fully Saved To-day” and put it on her old record player. She started singing along. “It was so clear,” Williams says. “Her voice was an older version of the one on the records. Her daughter Sam Faye walked in and said, ‘Mama, that’s you!’ ”

Williams made several trips to Marlin, and each time Harris provided more information. She said she had married Johnson in 1926 or 1927 and that he’d been blinded by looking at an eclipse through a piece of glass. She mentioned that Johnson had played guitar and piano at the Church of God in Christ on Commerce Street and that he had had a partner named Blind Madkin Butler, an evangelist and fiddle player from Hearne. She insisted that Johnson wasn’t a preacher, “just a songster.” She told of helping her husband buy new guitars—he was picky—and about taking the train with him to Dallas for his second session, in 1928, the first one she sang on. (They stayed at the Delmonico on Elm.) She said the marriage had ended in 1932 or 1933 and that he had moved to Galveston, where, as far as she knew, he kept a home base and continued traveling and playing on street corners. She said she received a telegram when he died. She didn’t know what killed him. He just “got sick and died.”

Williams never followed up on Harris’s claims, but he wrote up notes on his visits and sent them to several musicologists. Seventeen years later they wound up in the hands of Randy Harper, another Johnson devotee. Harper was a Houston blues fan who was drawn into Johnson’s orbit by Ry Cooder’s Paris, Texas sound track. When he realized Johnson had lived in Marlin, he began researching and trying to track down family members; then he drove there. By that point Harris was dead, but Harper found people who remembered her and Johnson. “She took real good care of him,” one told him. He also tracked down another daughter of hers, Dorothy, who cried when he played the music of her stepfather. Finally, in 1994, Harper followed the trail to Beaumont, where a day at the Jefferson County Courthouse turned up the holy grail for Johnson researchers: his death certificate.

But the piece of paper was full of surprises and contradictions. Johnson, it said, was born near Brenham, in Independence (not outside Temple), on January 22, 1897, to Willie Johnson Sr. (not George Johnson) and Mary Fields; he died in Beaumont on September 18, 1945 (not 1949), and was buried in Blanchette Cemetery. Contrary to Harris’s claim, he was a minister. For thirty years, it said, he had lived at 1440 Forrest Street, the same address Angeline had mentioned. And he had died of malarial fever; contributing to his death were blindness and syphilis (spelled “spyphilis”). Oddly, the informant on the death certificate, the person who gave this information to the funeral home director, was Angeline (spelled “Angilena”) Johnson, who ten years later gave Charters almost entirely different facts.

The death certificate is a perfect example of just how unknowable Johnson truly is. Still, more than half a century after his death, people are trying to figure him out. In 2003 Michael Corcoran, a self-described “obsessed rock and roll detective,” joined the search. Corcoran, a longtime writer for the Austin American-Statesman, had become fascinated by gospel music, doing stories on Rebert Harris of the Soul Stirrers, pianist Arizona Dranes, and Washington Phillips, a gospel singer who was a contemporary of Johnson’s (in fact, the two had shared a session in 1928). Corcoran loved Johnson’s guitar playing and was incensed that bands like Led Zeppelin had made millions copying him, while he remained a cipher. “I thought, ‘How come this guy isn’t as big as Robert Johnson?’ ” So Corcoran was off: to Marlin, Temple, Waco, and Beaumont, where he found a 1945 city directory with a listing for a “Rev. W J Johnson” and a “House of Prayer”—a small, home-based church, perhaps—at 1440 Forrest Street.

Corcoran learned from Williams that Johnson and Harris had had a daughter and that she had recently moved back to Marlin. It was Sam Faye Kelly, the woman who had recognized her mother’s voice on the turntable a quarter of a century before. Corcoran visited her in the house that Johnson and her mother had shared back in the thirties. Even though searchers had been there before and the trail was long cold, he was certain, he told me, that he was going to solve the mystery. “I was thinking I was going to stumble on a footlocker with fifteen pictures of Johnson.” He didn’t. Kelly, who was born in 1931 (she showed Corcoran a birth certificate that listed her father as Willie Johnson, “musician”), didn’t remember much about her father anyway. “I was just a little girl when he went away,” she said. But she was certain that the couple had remained married—even as her mother had children with other men—and that he had stayed in Marlin until 1938. She said that he had made his living by traveling and singing, going from town to town, corner to corner, church to church, revival to revival. But after he left, he was gone for good. She never saw him again.

“The Soul of a Man”

It was a bright, hot Beaumont morning in July, but inside the dense forest adjoining a dilapidated cemetery on the north side of town, it was as dark as a cave. From a few yards away, this patch of vegetation looked like just another wild urban space. Yet as I pushed past the branches, I saw headstones poking out of the ground. I climbed over a fallen tree trunk and entered the gloom: There were more stones as well as long concrete slabs covered in vines and leaves. I was able to crawl my way to a handful of them. I brushed away the leaves and saw that a few stones had names—one said “Rev. T T Benson, Died August 25, 1930.” But I was searching for one name in particular.

I found myself communing with the dead in this ancient Beaumont graveyard because I too had begun searching for Johnson. Again. I had made a desultory attempt to find him ten years ago, as part of a story I’d done called “Birthplaces of the Blues,” in which I drove around Central and East Texas, writing about people like Johnson, Jefferson, Hopkins, and Lipscomb. Of course, in my story I repeated the same errors everyone else had, saying Johnson was born near Marlin in 1902 or 1903 and that he died in 1949 of pneumonia.

Then, last year, I read that Johnson’s grave had been found in Beaumont and that the Jefferson County Historical Commission was putting up a historical marker. Not long after, I learned that two fans from Austin—a young couple, Shane Ford and Anna Obek—were also putting up a marker to Johnson. The great man was finally getting his due.

I drove to Beaumont this past July to rendezvous with Ford and Obek, who were doing more research. I also met Les McMahen of the JCHC, who offered to show me around town. Our first stop was 1440 Forrest, the former home of Johnson and the House of Prayer. The building doesn’t exist anymore; today the address is a grassy area on the side of a narrow blacktop next to the Pilgrim’s Rest Baptist Church, sitting in the shadow of Interstate 10. Directly behind the spot where the House of Prayer stood is a five-foot mesa topped with three crosses. The only home on the entire block is across the street; the man who answered the door had never heard of Johnson. Except for the rumble of I-10, we could have been out in the country. Forsythe Street, where Johnson used to play for change, isn’t far away, and we drove there too. But the buildings and homes that had made it such a thriving black district in the forties had been torn down in the eighties.

McMahen, who was born and raised in nearby Port Arthur, had never heard of Johnson before last year. Now, because of the historical marker process, he’s become a searcher too, fruitlessly scouring old newspapers for obituaries. He and I went to the Fire Museum of Texas, which has the world’s largest fire hydrant out front. Inside we searched through scrapbooks of newspaper clippings from the mid-forties, looking for anything about a fire that damaged 1440 Forrest and preceded Johnson’s death. There were pictures of a big fire at the Perlstein Building and of the fire department’s bowling team, but nothing about 1440 Forrest. McMahen later checked the department’s fire call records; there was nothing there either. Given the time and place, though, it’s not surprising that there were no records of a fire in a black neighborhood—or an obituary of a black citizen.

Later that afternoon Ford and Obek joined us at Blanchette Cemetery, Johnson’s supposed resting place. The field, on the south side of town, was rutted and troughed and had no sign giving its name; many headstones were teetering or had already fallen. Maybe one of every four stones had a name on it, and some of those had been scratched into the stone by hand. The layout was total chaos. After walking through areas dense with stones, we passed through wide-open spaces where the grass changed hues of green several times in a space of twenty feet and the earth sank an inch or two. It was obvious: There were many unknown corpses down there. Across the street there were several other similarly shabby fields of stones.

This was Ford and Obek’s third fact-finding trip to Beaumont and the cemetery; they had spent hours at the courthouse, analyzing deed transfers and ancient city maps, some of which didn’t even show old black cemeteries, trying to determine where exactly Blanchette was. Like McMahen, neither of them had heard of Johnson until recently. In their case, the moment of revelation came in the fall of 2006, when they saw a documentary called The Soul of a Man, which focused on Johnson and the bluesmen J. B. Lenoir and Skip James. Neither Ford nor Obek was much into blues or gospel—he liked metal, she liked Cat Stevens—but the song “Soul of a Man” hooked them. It sent chills through Ford and made Obek cry. Johnson was their ticket to the world of country blues, and they took a road trip through the state to see the graves of men like him. Blind Lemon Jefferson had a big stone in a Wortham cemetery and Lightnin’ Hopkins had a statue in Crockett. But when they got to Beaumont, they found nothing. After walking through this dilapidated cemetery, they returned to Austin, determined to erect a monument to Johnson.

But their plans were complicated last year when Jack Ortman, an Austin music historian who had spent years putting together book-length compilations of stories written about the psychedelic rock pioneer Roky Erickson, announced that he had found Johnson’s final resting place. Ortman grew up in Beaumont and returned often to visit his mother; he was a fan of local musicians such as Janis Joplin and Gatemouth Brown and wanted to see Johnson get his due. He had spent more than a year poring over maps and tromping through the town’s old cemeteries. He interested the JCHC in putting up a state historical marker, but the commission told him he had to find the exact burial spot. By July 2009 Ortman had narrowed his search to a 25-foot-by-25-foot unkempt area with no stones at all—located across the street from the graveyard Ford and Obek had been studying. This lot, Ortman believed, was a pauper’s section of Blanchette, and given that Johnson was poor, Ortman figured by a process of elimination that he must be down there. “All the other places have marked graves,” he told me.

I followed Ford and Obek across the street as they took me to this unmarked lot, which according to their map is known as Nona Cemetery, not Blanchette. But they had recently encountered another complication: a second Blanchette cemetery (“Blanchette #2”), in the northern part of the city. We drove there too. Again we found teetering stones and many shades of green, as well as the adjoining patch of urban jungle that I wound up exploring.

Earlier this year the JCHC concluded it would never determine the exact location of Johnson’s grave, so members opted to memorialize the House of Prayer, at 1440 Forrest Street. The marker will go into the ground in a ceremony sometime this month. Meanwhile Ford and Obek decided to put up a private memorial, a cenotaph, at the original Blanchette Cemetery. They started a foundation, held a benefit in Austin in July, and raised $3,500. They plan on installing it in March. Ford and Obek are pretty certain Johnson is buried in Blanchette. Pretty certain. “He could be in Blanchette or Blanchette Number Two,” Ford acknowledges. “He could be anywhere. We have no idea.”

“Jesus Make Up My Dying Bed”

At a certain point Ford and Obek stopped trying to find out what happened after Johnson’s death and started trying to piece together his life. Ford went to Dallas, Temple, and Marlin and studied city directories and county documents. He found evidence that Johnson and Harris had lived together: a 1930 census report showing Johnson living in Marlin as a boarder with Willie B. Harris and her two children—the year before Sam Faye Kelly was born. He was 33, it said, which fits with someone born in 1897.

And Ford thinks he may have solved the mystery of Johnson’s parents. Earlier this year he found a 1915 Temple city directory that listed a Willie Johnson (followed by a c for “colored”) who lived in the same house with a Doc Johnson and his wife, Catherine. Ford had heard Doc’s name before. In 2007 a blues fan named Jeff Anderson had found a potentially revelatory document—a copy of a 1918 draft card for a blind man named Willie Johnson who was living in Houston and whose father was named “Dock.” According to the card, Dock was from Valley Mills, a town twenty miles northwest of Waco. Ford knew that the 1910 Temple census reported a Dock and Catherine living there with four children: Wallace, Robert, Carl, and Mary. That document didn’t mention a Willie, but a 1935 Temple directory listing for a Willie Johnson, musician, residing at a house on South Fifth Street, mentioned four other Johnsons living there as well: Wallace, Robert, Carl, and Jettie. Ford also found a death certificate that listed Jettie as the daughter of Dock and a woman named Mary King and death certificates for Carl and Wallace that listed their mother as Mary King. He learned that Dock Johnson had married King in 1894. Then he found that Dock had married Catherine Garrett in 1908. If you put the pieces together, they seemed to tell a story.

I spent a couple of days with Ford driving around Central Texas, trying to find something—anything—that might have been overlooked during the previous 55 years. The draft card said Johnson was born in Pendleton, a hamlet in Bell County, just north of Temple, so Ford and I drove to Belton, the county seat. The clerk in the supermodern county clerk’s office checked her records and said that, yes, they had a record of a Pendleton birth to a Dock Johnson and a Mrs. Johnson. As she went back to make a copy, Ford and I were so excited we fist-bumped. But the document she returned with simply listed the baby as “Neg[ro]—male.” And the date was December 28, 1903.

We drove to Brenham too. I’d noticed on the 1930 census form that Johnson was listed as divorced—and he’d apparently told the census worker that he had first been married at 21, which would have been around 1918, well before he met Angeline or Willie B. Then Ford found a listing for a Willie Johnson marrying a Julia Smith in 1917 and having a daughter named Mertha. Dock’s death certificate, which Ford had found in February, noted that a woman named Martha had been the informant. That was enough to justify a trip. But when we got to the Washington County courthouse, we found that this Willie Johnson had a middle name, Earl. Ours, to the best of our knowledge, didn’t. The town of Independence—Johnson’s birthplace, according to his death certificate—is also in Washington County, so we checked the county birth records too but found no Willie Johnson born in 1897.

We spent an afternoon in Marlin. The Wood Street area, where Johnson had played in the Depression, had been bulldozed in the nineties and was now mostly empty lots and concrete slabs. His church, the Church of God in Christ, was still standing. A neighbor across the street remembered services there in the forties. “It’s a sanctified church,” said J. C. Williams. “They would do all the holy dances, shout, fall out, roll around.” We talked to several elderly folks; none remembered Johnson, but many recalled Harris. We went to the house where she and Johnson lived. It was a trashed-out wreck—the roof had fallen in, the walls were caving, and the yard was overgrown with tall weeds. Eighty years ago this was the home of one of America’s greatest musicians. Now the only things living there are wasps and rats.

“God Don’t Never Change”

After all these years, here’s what we know about Blind Willie Johnson. Well, here’s what we’re pretty sure about. Assuming that that draft card didn’t belong to another blind Willie Johnson, he was born in Pendleton, Texas, on January 25, 1897, to Dock and Mary Johnson and grew up in Temple and Marlin. Blinded at a young age, he found one of the only occupations available to people like him: musician. He played on the streets of nearby towns and cities—and was very good at it. Assuming a later census worker took down Johnson’s replies correctly, he married in 1918 or so. He wound up back in Marlin—where, if you believe Willie B. Harris, he married again and played in church and on the streets. He recorded thirty amazing songs. He fathered a daughter. Somewhere along the way, if you believe Angeline Johnson, he married for a third time. He left Central Texas for the coast and eventually made it to Beaumont. He kept playing his music and died, on September 18, 1945.

Of what, though? This is one of the bigger mysteries of Johnson’s life. McMahen doesn’t think Johnson died of malarial fever, as his death certificate says. “That doesn’t ring true,” he says. “Pneumonia makes much more sense around here.” His wives are another mystery. No certificates have been found for his marriages to any of them—his unknown first wife, Willie B., or Angeline. Charters takes an accepting attitude to Johnson and Angeline’s relationship. “I would be surprised if, in the eyes of white society, Willie and Angeline were ‘married,’ or if it mattered,” he says.

And what to make of the fact that both women claim they were married to him in 1927? Dan Williams thinks this isn’t so far-fetched. He visited Harris several times and says that on each visit, she grew more reticent. “She seemed less and less to want to see me or talk about Johnson. I think it’s because he was living two lives—she had a wounded heart and bad memories.”

As for what caused Johnson’s blindness, I found no records for a total solar eclipse visible in Central Texas from 1897 to 1910, though there was a partial eclipse in 1900, when Johnson was three. But it’s difficult to imagine a child that young staring at the sun long enough to go blind—even if he was looking at it through a shard of glass from, say, a green soda bottle. As for the lye scenario, the draft card, issued when Johnson was 21, provides an important clue: “States was blind 13 years.” But does that mean at age 13 or for 13 years? If the former, that puts the event in 1910, after Dock had remarried and Willie had a stepmother, Catherine, which fits with Angeline’s dramatic tale. If the latter, that means it happened when he was 7 or 8, which at least matches the age at which she said he lost his sight.

In some ways, Angeline is the biggest mystery of all. I could find only one document that mentioned her while he was still alive, a 1941 Beaumont directory listing a William Johnson and an Angeline Johnson residing at 555 Forsythe, the St. Charles Hotel, a boardinghouse. To make matters weirder, the 1945 city directory lists Johnson living at 1440 Forrest—but the woman living with him is listed as “Antonia.” Ten years later, Charters interviewed Angeline at her neighbor’s house, at 2525 Euclid. The 1956 city directory lists “Angelina” Johnson as living at 3110 Houston, which is two doors away. One year later, the directory shows the person living there as Antonia Johnson. She was a widow, the directory noted, of a man named Henry.

“Bye and Bye I’m Goin’ to See the King”

Does it matter who Angeline—or Angelina, or Antonia—was? Does it matter where Johnson was buried—Blanchette or Blanchette #2? Or where he was born—Pendleton or Independence? Would finding a hospital record of a boy blinded by lye explain the man’s music?

Maybe. Granted, the desire to know everything about our heroes is not always a healthy pursuit. But the fact that Beethoven was deaf when he composed the Cavatina makes his music even more moving. How Johnson, this blind, second-class citizen, made such astonishing music, how he lived, played, loved, and died, seem to me to be essential details.

That’s true even if, as I learned repeatedly in my search, many details only make things more confusing. But I was certain I was one fact away from discovering something important. So I kept looking, even after Ford told me in mid-October that he was done. I went to an online genealogy site and spent a morning looking for Antonia Johnson. Nothing. I went to the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, in Austin, and scoured ancient Marlin and Temple newspapers. Nothing. I went to the state library to pore over city directories, trying to find evidence of Johnson’s living in Galveston, as Harris had said he had. I found several Willie Johnsons, but I knew that was a common name. Maybe he lived there, maybe he didn’t.

As I was about to leave, I remembered a story the musicologist Mack McCormick once told about Johnson playing a song called “Can’t Nobody Hide From God” over a Corpus Christi radio station during the early forties, when people on the coast were terrified of German submarines lurking in the Gulf of Mexico. So I pulled down a Corpus city directory from 1937—and sat down in shock. There it was:

Johnson, Wesley

Johnson, Willie, (c), (Annie) musician

Johnson, Willie Lee

Maybe the landlubber Harris had confused Corpus for Galveston. Maybe Johnson had stopped in Galveston and then continued on to Corpus. Maybe “Annie” was Angeline. Or Angelina. Or Antonia. I checked other Corpus directories and found no mentions of Willie Johnson, musician. But that didn’t mean anything at all. He could have been there. He probably was. He might as well have been.