About halfway through the drive from Austin to Smithville, Andrew Shapter pauses the conversation to be sure I understand. To make movies, he says, you have to be skilled at telling stories. But the story behind your story, he emphasizes, is just as important, particularly for a guy who plays the role of director, producer, and promoter, all at once. “When you’re making an independent film and you don’t have stars, it better be interesting—or the stories around the making of it better be interesting—or you’re not gonna have anything to go with.”

On March 1, after brief theatrical runs in a few cities, the Austin documentary filmmaker’s third movie, The Teller and the Truth, will become available for streaming and downloading. The film’s promotional materials describe it as the “haunting true story of a beautiful bank teller who disappeared in 1974 in Smithville, Texas,” and an “unusual blend of documentary, narrative, and silent film.” But those descriptions barely hint at how unusual the film actually is.

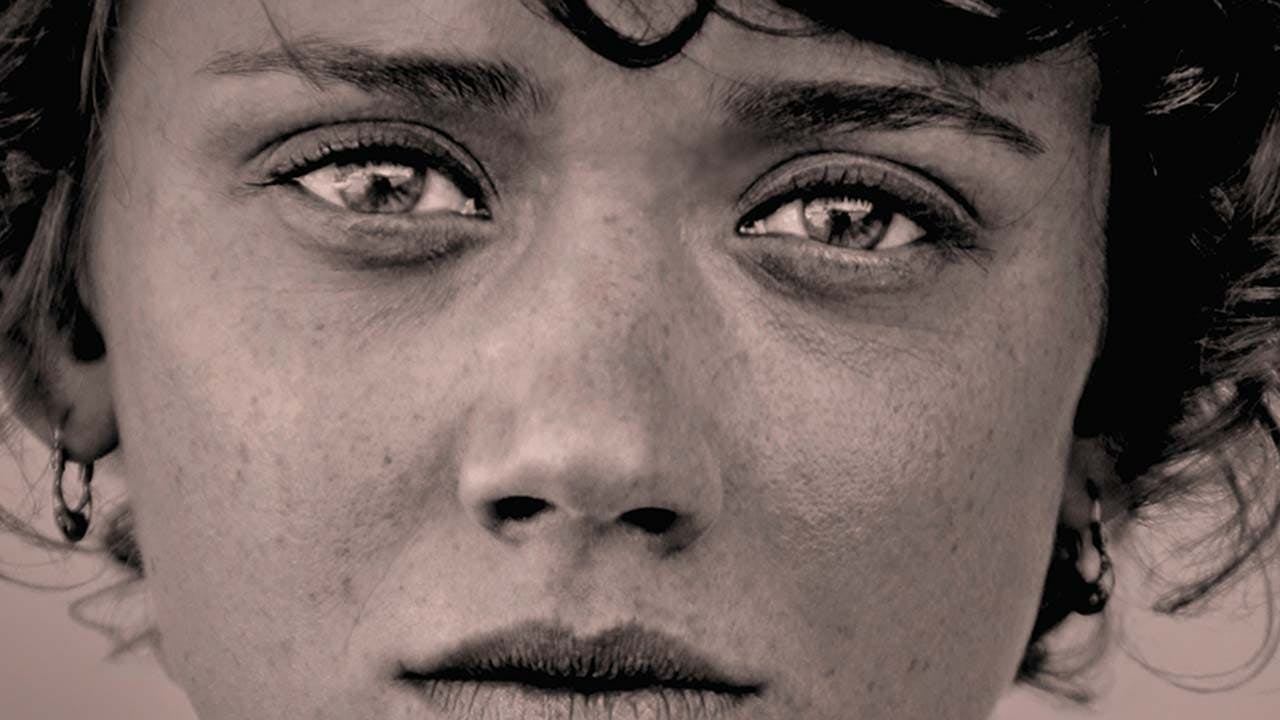

By one measure, the story of Shapter’s search for that beautiful bank teller began in 2010, when he uploaded a striking image of a young woman from Smithville named Francis Wetherbee to the photo-sharing website Flickr. The picture, he wrote in a lengthy caption that accompanied the image, had been taken by his uncle Paul Amos McQueen, a local photographer, on March 3, 1974. “I lost count of how many times he told me her story,” Shapter wrote.

Shortly before Wetherbee’s picture was taken, Shapter related, there had been a robbery at Smithville’s First State Bank, where she worked as a teller. She arrived at the studio looking distressed, and soon after, she disappeared, never to be seen again. “There are so many unanswered questions,” Shapter wrote.

The response was tremendous. The picture went viral, particularly on Tumblr, where it was shared thousands of times. Shapter had been trying to make a movie about Wetherbee for some time, and the intensity of the response convinced him to keep at it. Wetherbee’s story resonated with people in a deep way. Had she been murdered? Did she disappear of her own free will? Was she complicit in the bank robbery?

Around the same time, Shapter wrote an article about the problem of missing persons for the Huffington Post. Naturally, he wrote about Wetherbee. “I can’t get her eyes out of my mind,” he wrote. “Francis represents the many missing faces who have loved ones still searching for them today. Loved ones still searching for answers, still looking for clues, still hanging on to hope.”

In late December, as Shapter and I were driving around Smithville to see some of the places that shaped his film, he explained—to my surprise—that The Teller and the Truth isn’t exactly a “true story.” Though the film was inspired by a real person and a real event, he said, much of it is fictional—not just the second half, which imagines what Wetherbee’s life was like after her disappearance, but also the first half, which has the patina of a documentary.

Still, Shapter emphasized, his film hews to the rough outline of Wetherbee’s story. But as we drove around Smithville, our conversation took some odd turns. As we talked, I realized that I was unsure, at certain moments, whether we were talking about Shapter’s creation or the real woman or both. Wait, I asked, who is Francis Wetherbee? “Francis Wetherbee is my grandmother’s name,” Shapter said. Then things got odd.

The line between fiction and fact began to blur for Shapter in 2009, at a Smithville bed-and-breakfast. Shapter was scouting locations for his first feature film, which he hoped would be the fictional story of a woman from a small town who had helped rob the bank where she worked and then disappeared.

Funnily enough, he says his hosts told him, something a lot like that had happened there many years ago. A woman who’d been working as a bank teller allegedly got her boyfriend to rob her employer. She was interrogated but skipped town before charges were filed and was never seen again.

Later, Shapter says, David Herrington, a local historian who is interviewed in The Teller and the Truth, showed him a picture of the woman—posing, memorably, with her midriff bared—in an old Smithville newspaper. But her tale dead-ended after that. “There’s no more to that story other than she was brought in for questioning,” Shapter tells me. So Shapter filled in the details. He decided to give the woman his late grandmother’s name because he thought that attributing fictional incidents to a real person would invite a lawsuit. And that 1974 photo that he posted to Flickr? It was actually a photo he took in 2010 of Leilani Galvan, an employee at an Austin juice bar he frequents. (Shapter does not have a photographer uncle named Paul Amos McQueen.) He calls his creation of the Wetherbee myth a “social experiment.” He certainly didn’t expect it to blow up like it did.

But when it did, he kept it going. In February 2011, he gave an interview to the Austin radio station KOOP, which knew what he was up to, in which he presented what he claimed were new findings in the Wetherbee case. He suspected, he said, that she had fled Smithville voluntarily. “There was just a tension between [Francis and her mother] that would make you suspect that anybody in their right mind would want to escape that scenario,” he told unsuspecting listeners.

Interest in Wetherbee’s case grew, and she developed a following on social media that Shapter describes as almost “cultlike.” One man contacted Shapter, he says, to tell him he had a crush on the missing woman. Others painted portraits of her, some of which now hang in his Travis Heights home. Shapter says the painters, who were “a little confused,” sent him their art as a gift.

People went looking for Wetherbee. Her case was debated on sites like websleuths.com, where armchair detectives attempt to solve real crimes. Several tried to fill in the narrative Shapter had provided. One found a woman named Francis living with a man named Oliver in the UK and thought it might be her. Some thought Wetherbee had escaped to a new, happy life; others figured she had met a grisly end.

At one point, Shapter says, the Smithville Police Department got a call from a person who’d read about some bones that had been found in a gulch in Harris County. Could that be her? An entry for Wetherbee appeared on the Doe Network, an international database of information on missing persons. Eventually, Shapter contacted the network and asked it to take down the entry, admitting that the whole thing was an elaborate fiction. When word got back to some of her followers, they reacted with disappointment. “What a terrible deception,” wrote one Websleuths user.

The attention was thrilling for Shapter, who decided that the mix of fact and fiction was worth exploring on film, using a variety of cinematic styles to leave the audience wondering what was real and what wasn’t. Shapter says he had actors read lines about the bank robbery that real people had spoken to him, but the lines were sexed up a little. In the movie, Wetherbee (played by Galvan) is about to enter a loveless marriage before she splits; Shapter acknowledges he made that up. In one scene, a witness who was injured in the robbery is shown sitting in a wheelchair. In real life, no one was injured, though Shapter assures me that there was a shoot-out during the real robbery: “Bullets were flying.”

Herrington, who Shapter claims knew the real woman, talks in the film about Wetherbee’s tenacity, but he’s given a fake name. It turns out that, encouraged by Shapter, he was actually talking about his granddaughter, who has never robbed a bank. When Shapter and I sit down to speak with him in Smithville, I ask him about the woman in the newspaper photo that Shapter says Herrington had shown him years ago. He responds with confusion, then seems to deny knowing her personally. Later, Shapter tells me he wonders if Herrington was pretending, perhaps to keep the woman safe. But he offers no evidence for this claim. Is it true? Does Shapter believe it? Or is it just a good plot twist?

What better place for this story about a story than Smithville, perennial home to film productions, where Sandra Bullock’s house from Hope Floats sits just a few blocks away from Brad Pitt and Jessica Chastain’s from Tree of Life. Shapter shows me the latter, a small wooden home that served on-screen as the cradle of an operatic retelling of the grand cosmic cycle of life and death. Its porch is occupied only by a big foam Buc-ee’s cooler, its cartoon beaver facing the street.

While making The Teller and the Truth, Shapter sometimes represented it as a documentary. When he was filming scenes in Live Oak County in 2010, a local newspaper duly provided the outline of Wetherbee’s story. Shapter, oddly, seems to have told the paper that the robbery took place not in Smithville but in Arcadia, which he says he intended to be a fictional town—though there is a real Arcadia in Texas. When the film was submitted to the Toronto International Film Festival in 2014, it was erroneously considered as a documentary. (Shapter says this was a misunderstanding.) And this past fall the film’s publicity firm, Brenda Thompson Communications, sent out an email filled with phrasings whose ambiguity likely escaped most recipients. It quotes Shapter as saying, “When I first saw Francis’ picture, I had to know more and never looked back”—even though Shapter never “saw” Francis’s picture; he took Francis’s picture, and the picture wasn’t even of Francis.

But the movie is based on a true story, right? Since Shapter had told me that the robbery took place in 1974, I went to the local public library a few weeks after our trip to Smithville to look through old copies of the Smithville Times. Perusing the issues from 1974, I found a lot of editorial cartoons about the oil crisis but no mention of a bank robbery. Editions from 1973 and 1975 had nothing either. The First State Bank is now shuttered, so no one there could help me out. A few Smithville old-timers I contacted had no memory of the robbery, and city hall and the Smithville Police Department disagreed about who is responsible for keeping records of decades-old criminal incidents.

When I followed up with Shapter, he told me that the origin of his film “will get even more unusual the more you dig.” He offered to give me further detail but reiterated that he was worried about libel suits. I should keep my description of the robbery spare of detail, he advised, because “vagueness could trigger a lot more interest in your story.” At one point, he sent me an article about some Krugerrands found near Bastrop that he thinks might be connected to “the actual robbery in 1974.”

A few days later, I got a call. “I guess I’m the only one who was working at the bank who’s still living,” says Billie Williams, a former teller at First State. After my inquiries at the police station, a kind dispatcher had called around until she found Williams, who, it turns out, was interviewed by Shapter for The Teller and the Truth and makes a brief appearance in the film. The movie, she says, is “totally fabricated.” She doesn’t mind, though.

On June 16, 1972—not 1974—Williams was working at her window when two women, one armed with a rifle, ran in yelling like banshees. A couple of bank employees ran out a back door, and one of the robbers fired a bullet in their direction, which ricocheted around and lodged in the wall near the vault. “We had customers in the bank, and one of the robbers grabbed one of them and told her, ‘You’re gonna die,’ ” says Williams. “There was an old man who was up in age and kinda feeble and she told him to lie down, and he said, ‘Are you kidding?’ ”

The women grabbed some cash, jumped in the back of a car that was driven by a male friend, and hauled ass in the direction of La Grange, where—according to a front-page story in the June 22, 1972, edition of the Smithville Times—they were immediately arrested by the sheriff. There was no shoot-out, nobody was hurt, none of the perpetrators worked at the bank, and, according to Williams, all of them went to prison. She doesn’t know what happened to them after that. But she’s pretty sure no Krugerrands were involved.

“The Teller and the Truth is basically a collection of people telling a collection of stories,” Shapter explains when I ask him why he has misled so many people about so many things. “Some people are telling true stories. Some people are telling fictional stories. It’s not necessarily a movie about a bank teller. It’s basically a new way of making films.” Shapter believes this new technique will be used by other filmmakers, and he speaks about it with elation and passion. He hopes, as he says was suggested to him by his co-editor, Sandra Adair, who has worked on many of Richard Linklater’s films, that the movie “will be studied for years to come.”

His next project, which he aims to do in the same documentary-ish style, touches on tough subjects: a closeted Texas oilman, abuses perpetrated by the Texas Rangers, and long-suppressed racial injustice. He worries, though, that people might be too uncomfortable to talk frankly on camera. So he’ll do it “exactly like this,” he says: He’ll approach people who knew the allegedly gay tycoon. He’ll ask them to talk about a fictional character who resembles their friend. And in that way, he’ll get at the truth without having to tackle it head-on.

“Fiction writing is great,” Shapter says. “But there are just so many real true stories out there that are so fascinating.”