This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

About noon on the day after Fred Carrasco seized ten hostages and garrisoned himself in the library of the Huntsville prison unit known as The Walls, a lean and lighthaired male citizen, 29 years old, left Austin for the San Antonio offices of James Gillespie, Carrasco’s lawyer. The latest news across the AP wire was that Carrasco had demanded additional weapons and body armor by three o’clock or he would kill his hostages. The citizen had reason to believe that phone contact might be made between Gillespie in his San Antonio office, Governor Dolph Briscoe in his Austin office, and Carrasco in the prison library. The citizen wanted to sit in Gillespie’s office and listen during these calls.

He left for San Antonio with some reluctance but was spurred on by something more than idle curiosity. Last March, after Carrasco had been sent to Huntsville, the citizen had spent a long month running around San Antonio trying to piece together the story of Fred’s life. The project was a grim one. Fred had left a bloody trail from San Antonio to Nuevo Laredo to Guadalajara and back to San Antonio again. Estimates about the number of men Fred had either killed or ordered killed ranged from a high of 57 to a low of 40. His first was when he was eighteen; a young girl lured a man out of a San Antonio dance hall and Fred shot him. Antonio de la Garza, who would later be a lieutenant in Fred’s heroin smuggling operations, witnessed the killing. That was in 1958. In September of 1971, Fred had de la Garza killed. He chose another lieutenant, Pete Guzman, for the job. Guzman not only killed de la Garza but also mutilated his pregnant wife. About a year later, after Guzman had started bragging that Fred was now taking orders from him, he was found in a ditch in Mexico dead from 45 bullet wounds. Many of Fred’s killings were like that—murders of gang warfare, murders in response to real or imagined affronts, murders of discipline within the gang—and no amount of friendship or service was insurance against Fred’s blood lust: the murdered de la Garza had known and worked with Fred for fifteen years.

Fred served two years for the dance hall murder and was paroled in 1961, but in April of 1962 he received eight years for possession and sale of heroin. After serving five years of that sentence he was paroled in 1967 and returned to San Antonio. For the next five years he and his gang, who called themselves the Dons, dealt in increasingly large amounts of heroin while Fred, now a fugitive for violating his parole, split his time between San Antonio and Nuevo Laredo. His presence on the border ultimately caused open warfare as Fred tried to expand his power over two older Nuevo Laredo gangs, the Gaytans and the Reyes-Prunedas. The fighting became so violent and so open that in the spring of 1972 the Mexican government sent squadrons of federal troops into the city. The rival gangs were, by this time, either arrested or dead or in exhausted disarray, and by fall the fighting was over. (See “The Laredo–San Antonio Heroin War,” Texas Monthly, August 1973.)

Fred found himself caught between what was left of the two older gangs and the federales, and he got into further trouble with the Mexican underworld when a member of his gang got arrested and started spilling trade secrets to the authorities. Fred moved on to Guadalajara where the final sequence of events that culminated in the Huntsville siege really began and where Fred’s only redeeming quality, his devotion to his wife, first became publicly apparent.

What happened in Guadalajara was that Fred and assorted gang and family members were arrested on September 20, 1972, with 213 pounds of heroin (street value: $100 million) and enough guns for a whole army of bandidos. Fred’s wife Rosa was also captured in this haul, but Fred had no respect for any man who would let his wife languish in jail. He held a shard of glass against his throat for five hours until lawyers negotiated her release. Fred had good reason for wanting her out. His half-brother, Robert Zamorra Gomez, was found dead in his cell hanging by the neck from his own belt, even though that belt had been confiscated when Zamorra was booked. Fred accused prison officials of murder.

In December Fred escaped. Four confederates from San Antonio drove to Guadalajara with bribe money and Fred made it through the gate hidden in a laundry truck. He headed straight to San Antonio. He was convinced that he had been cheated by his gang while he was in jail, that his authority was threatened, and he knew only one way to deal with that situation. He started killing again. On March 10 he walked into an ice house where Gilbert Escobedo was drinking. Escobedo, formerly sort of a treasurer for the gang, had held back $80,000 from a heroin deal while Fred was in jail. Fred drew two pistols and used them both.

On April 8 he ordered Agapito Ruiz and Roy Castano to take him for a drive. They rode in the front seat while Fred and at least one other person, Joe Richard Garcez, a young dealer who had carried the money down to Guadalajara to bribe Fred’s way out of jail, rode in the back. The police had been following Agapito very closely and had even gone so far as to place an electronic beeper on his car. Agapito discovered the device and took it to his attorneys, who returned it to the police. But Fred thought he had turned informant. As they drove along an obscure road south of the city, Fred pulled out a gun and shot them both.

Afterward Fred ate a steak dinner, but the killings had made Joe Richard sick. He had to leave the table to vomit in the men’s room and was still sick the next morning. A Viet Nam veteran with decorations for bravery, he had gotten into the dope traffic for the money and the excitement. He liked to spend lavishly on his friends and maintained several women in their own apartments. But these killings were too much for him. He mentioned them to friends with horror.

Joe Richard always worked with David Garcia, a friend since childhood. On June 8, on another lonely road south of the city, Fred shot them both. They had been talking too freely about the Ruiz-Castano killings and about leaving the gang because of them. That made five murders in less than four months.

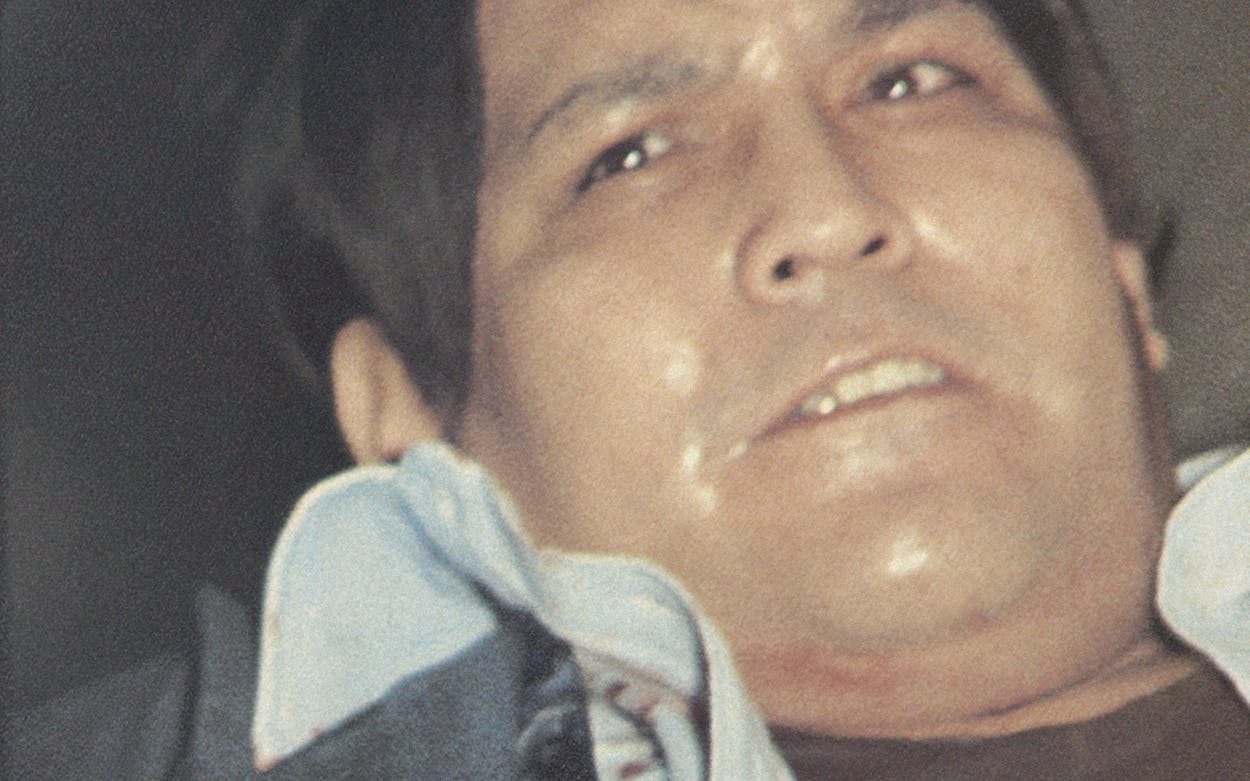

Stories began to circulate that Fred had a death list of twelve names and was going down it one by one. His name began appearing frequently in local papers and his capture became a cause célèbre with the San Antonio police. They finally surrounded him, along with Rosa and two others, at the El Tejas motel on July 21, 1973, after 12,000 man-hours on the case. Although Fred drew his pistol when he saw the police, he never got off a shot. He was wounded three times, but managed to run about twenty yards before finally going down. He cursed and spat at the officers, who pulled him up and sat him in a chair to wait for an ambulance. When it arrived, Rosa and Fred threw themselves at one another. Rosa clutched Fred, huge diamond rings flashing on her fingers, and kissed him with elaborate passion. Behind her she could feel the arc lights of television filmmakers and hear the clicking shutters of newspaper cameras. She kissed her husband an extra moment, then wheeled and, while the cameras rolled, shot everyone the finger.

Many wondered why Fred hadn’t been killed that night. He had openly vowed that he wouldn’t be taken alive and that he would kill as many police as he could before going down himself. In the weeks following the capture many came to wish that he had indeed been killed. Fred became surrounded by a labyrinth of plots and counter-plots that finally split the San Antonio police department into opposing factions, cast suspicion on the mayor’s office, and wrecked careers built through long years. Fred started the ball rolling in the ambulance that took him away from the scene of his capture. He told the two officers who were guarding him that cops had committed the Ruiz-Castano murders and he had a witness who could prove it.

The citizen could not quite bring himself to wish that Fred had been killed the night of his capture, but he would not have wept over it either. Tracing the story of Fred’s life had been grim, frightening, and unrewarding. Even now, as he made for San Antonio where he hoped to be privileged to at least one corner of the triangular conversation between Carrasco and the governor and the lawyer Gillespie, the citizen went only out of some feeling of obligation to the work he’d done on Carrasco in the past. He was, in a sense, Fred’s hostage too.

Last March when he had first met Gillespie, the citizen had come away from the meeting not completely sure what he’d seen. He had been told of Gillespie’s reputation as an extremely able criminal defense attorney, particularly in the federal courts, who got his share of important cases in San Antonio and throughout South Texas. He had, for instance, defended South Texas political boss Archer Parr. But except for his voice, which was as deep and lulling and pleased with itself as Everett Dirksen’s, and except for the titles in the bookshelves which rose to the ceiling behind his desk, titles which indicated an interest in psychology (The Mask of Insanity) as well as in the techniques of his profession (How to Win Criminal Cases by Establishing Reasonable “Doubt”), nothing else about Gillespie even hinted at the kind of self-assurance the citizen had assumed would go with Gillespie’s reputation. He was taut, as if his nerves had been stretched into a jangling network just below his sallow skin. He swallowed occasionally from a plastic bottle of antacid; he complained about high blood pressure. The skin on his face hung in swollen folds. Looking to be in his late forties, of medium height and build with thinning, wiry black hair, Gillespie peered at the citizen through thick lenses in black plastic frames and complained that his eyesight wasn’t getting any better either. All in all he had the sunken and frantic air of a man for whom events were getting badly out of hand.

His large desk, which he sat behind throughout the meeting, was overrun with messy files stacked several feet high, piles of open mail spilling over one another, thick brown case reports, crumpled cigarette packages, desk-top calendars and little desk-top figurines, pens, pipes, and encrusted ashtrays lying indiscriminately on top of everything. This effusion spilled over into the office where available spaces on couches and along the walls were taken with more piles of paper and more thick files; every bit of it looked like it would, if let loose, flow out over the office floor and possibly overwhelm the world. Almost as if to buttress the walls against such a possibility, they were completely covered with myriad framed documents that at one time or another had been presented to Gillespie: everything from his law school diploma to his military commission to his membership in TWA’s Ambassador Club, perhaps 50 in all. The citizen sat down in a chair in front of the desk and began the interview in utter amazement.

Gillespie talked rather distantly about Fred, as if he were not sure what attitude to take toward his client. On one point, however, he wanted no mistakes: “You know it’s a funny thing about Fred”—he stopped to puff a cigarette, a pause that let the echoes of his voice settle over both of them—“in all the many conferences I had with Fred, he never mentioned narcotics to me. Never. Not once.”

That disclaimer left Gillespie with only one anecdote from all his many conferences with Fred, an anecdote of Fred’s passion for his wife Rosa. The lawyer and his client were conferring in the Corpus Christi jail after Gillespie had won a change of venue motion which had moved the trial away from San Antonio. Fred wanted to plead guilty to assault to murder and accept a life sentence; in return for that plea all charges against Rosa would be dropped. Gillespie advised Fred against pleading guilty. The important charges against him—murder, assault to murder a police officer—turned out to hang by very slender threads of evidence; and the evidence against Rosa, who was charged with assault on a police officer, was contradictory. But after Guadalajara, Fred did not want to bear the shame of having his wife go to jail a second time. Lucky for Rosa. When Gillespie repeated that he thought Fred and Rosa would win their cases, Fred said, “Can you promise me in writing that Rosy will go free?”

“Of course,” Gillespie told the citizen, “Fred knew very well that was something no reputable lawyer could ever sign.” Gillespie swiveled his chair halfway around and turned his head back to look over his right shoulder at the citizen.

Still, a written promise to Fred from his lawyer would have had the binding effect in Fred’s eyes of a blood oath. No reputable lawyer who knew what was good for him would sign such a thing. So Gillespie said, “No, Fred, you know I can’t promise you in writing. But it looks so . . .”

“Then I will plead guilty,” Fred said. “I will take life. I will take life upon life. Rosy must go free.” Carrasco knew that Gillespie’s own marriage had ended in bile; he leaned closer to his lawyer: “Jimmy, someday if you’re lucky, you will meet a woman you’ll die for. For Rosy I would die.”

The Romantic touches a deep nerve in Gillespie’s soul; even as he told the story to the citizen, tears appeared in his failing eyes.

“That sounds like a moving moment,” the citizen said lamely.

“Oh, it was. Well, you can see the way I am now. And it was very emotional then. Tears—” Gillespie’s hands jerked to his eyes and his fingers trailed down his cheeks along the paths of his tears. “—I was sitting there, overcome, and Fred put his arm around me and you know what he said? He said, ‘Look now who comforts who.’ ”

This time, arriving about 2:30, half an hour before Fred’s next deadline, the citizen found Gillespie’s office more orderly than it had been during that earlier meeting. The stacks of files and papers strewn about the room were gone and the heap on the desk had diminished, although it certainly hadn’t vanished completely. Gillespie himself, in a wrinkled shortsleeved white shirt and a thin black tie and shapeless aqua-blue trousers, was obviously feeling the pressure of the situation. He was very pale, he was distracted, his wiry hair stuck out here and there at odd angles; and every time he wanted a cigarette, which was often, he had to search across his desk and through his pockets before he found his pack and then had to search some more to find his lighter. His shoulders and chest sagged and strained so hard against his too-tight shirt that he looked from the waist up like a sack of grain.

The citizen sat down in the same chair across from Gillespie’s desk. Gillespie told him, “You can sit here as long as you like, but if I get a confidential call from the Governor I may ask you to step outside.”

“Well.” The citizen shrugged. They would cross that bridge when they came to it.

Two other lawyers, Alfonso E. Alonzo and Steve Takas, both associates of Gillespie’s, were also in the office. Neither one said much at first. Alonzo, a swarthy and handsome man about 40, dressed in burgundy, sat to the left of the citizen near the side of Gillespie’s desk. Takas sat on one of the couches against the back wall. He was younger than either of the other two—round-faced, brown-eyed, ambitious.

With Gillespie understandably distracted and looking at the phone expectantly every few seconds, and with Alonzo and Takas in the room, themselves simply observers too, the citizen found that he really hadn’t anything to say to anyone. When all was said and done there was nothing to do but sit and wait for the phone to ring and link them all with the prison library in Huntsville.

A desultory conversation ensued with Alonzo grinning slightly to himself and Takas sitting on the couch with his feet resting on a chair and Gillespie searching for cigarettes and casting yearning glances toward the phone. “Is the Walls a high security unit?” the citizen asked Gillespie out of desperation.

“No. I think it’s just medium.”

“That’s right,” Alonzo piped in. “No guns allowed except in the library.”

Then one of the lawyers proposed that a certain friend’s ex-wife, a woman all three men knew to be a problem, be offered to Fred in exchange for all his hostages. “She’ll start bitching about community property,” the lawyer said, “saying this gun is mine, that gun is mine, and Fred will surrender just to get rid of her.”

They laughed, but not very easily, since the clock was coming closer to three. The citizen had moved to Takas’ couch against the wall. The lawyers had, for some reason, started talking about attention to detail. Gillespie said, “Wherever I go on a case I always find out all there is to know about the prosecutor. Everything. What he likes to eat, where he went to school, what his marriage is like, what his weaknesses are, his strong points, everything.” Takas, who had been a prosecutor in San Antonio before going into private practice, innocently asked, “Did you find out all that about me?”

“I sure as hell did,” Gillespie said.

“Oh.” Takas puffed on a cigarette. He glanced at the citizen and then snorted. “Funny time to be finding all this out,” he said.

It was almost three and the phone still hadn’t rung when Joe Conant and Manuel Ortiz walked into the office. Conant is a federal prosecutor who had obtained indictments against Fred for conspiring to sell heroin while he was awaiting trial in the Bexar County jail. Ortiz, a local police narcotics agent, dapper and slight of build, not far from retirement, had done important work that led to Fred’s capture. He was one of the San Antonio policemen Fred had accused of murder. The other was Sergeant Bill Weilbacher.

When the story of the accusations hit the San Antonio papers, no one really understood why Fred had singled out Ortiz; but it was obvious why he had singled out Weilbacher. During his 24 years on the force, Weilbacher had developed a thorough and widespread network of informants whose information he digested with his own native intelligence and street savvy. His conclusions were nearly always accurate.

He and Fred were natural antagonists. Both were bigger than life, both had reputations of being the most cunning and toughest men in their respective worlds, both had inspired individual legends. Though San Antonio is the tenth largest city in the country, it is literally true that the place was not big enough for both of them.

Weilbacher is an imposing figure, to say the least. He stands about six feet tall and weighs 300 pounds. Nearly all that weight is in his shoulders, chest, and stomach; he moves around on his legs like some great Idaho potato on toothpicks. His face is narrow with a thin nose and eyes set close together, a high forehead, and thin, curly hair combed straight back. Folds of flesh hang from his jowls and below his chin so that he seems to have no neck. His jackets hang over his great bulk like circus tents and his ties do not hang straight down but rest on his belly, moulding themselves on its hills and dales. He chews his fingernails, squints his eyes into narrow slits as he talks, and, since his glances can pierce through a man like a needle through an insect, it is apparent that Weilbacher does not maintain his informants’ loyalty with sympathy and kind words.

Weilbacher was in Guadalajara when Fred was put in prison there, and he marched over to the jail wanting to see Fred. But among Fred’s effects when he was arrested was a Xerox copy of one of Weilbacher’s secret reports about Fred and his gang. The Mexican authorities knew only that Weilbacher’s name was on the report and, not wanting to take any chances, they threw him in jail with Fred. There Weilbacher saw Fred weep over the death of his brother. When Weilbacher got back to San Antonio, he told Fred’s parents that he had seen their son shedding tears. Fred considered this a devastating insult.

Although it was information from Weilbacher’s sources that led to Fred’s capture, the immediate publicity went to another San Antonio cop, Lieutenant Dave Flores. Flores was the one who shot Carrasco during the capture. Mayor Charles Becker took the opportunity to honor Flores with a plaque; police department wags said he should have been awarded a practice target.

Flores went to see Carrasco in jail. Fred was not at first particularly receptive to the Lieutenant, but that reluctance faded when Fred realized that Flores was ready to investigate Fred’s charges against Weilbacher and Ortiz. Flores asked Fred to produce his witness.

Flores lives deep in South San Antonio. It is a predominantly Mexican area, different from the west side barrio in that small pockets of white ethnic groups—Poles and other Eastern Europeans—control much of the area’s political power. From the South Side to a position of respect in downtown San Antonio is a very long road, but one Flores had decided to travel as far as it would take him. He would not be content, like Weilbacher, with reputation; Flores wanted rank.

Along the way Flores had made one very powerful friend, San Antonio wheeler-dealer and land developer Morris Jaffe. Jaffe cultivated Flores and his family, let them use his lake house on weekends; and Flores returned the friendship even though Jaffe is not the sort police usually meet and greet socially. Jaffe bought the remains of Billie Sol Estes’ financial empire in 1962 for $7 million, subsequently developed uranium interests, and later promoted an immensely successful shopping center in San Antonio. But he also has had some questionable business associates. He owned an interest in the insurance firm Cohen, Kerwin, and White. Cohen has convictions for mail fraud. Kerwin, whose real name was Leroy Silverstein, had convictions for fraud and income tax evasion. Kerwin had had long associations with organized crime; and when he was murdered—executed, in all probability, by a mob enforcer—in Canada in late 1970, his briefcase contained documents disclosing various Mafia-connected swindling schemes. These have become known as the Kerwin papers. The firm Cohen, Kerwin, and White insured for $15 million an Oklahoma rancher named Mullendore who was later mysteriously murdered. Jaffe is also acquainted with Carlos Marcello, the Louisiana underworld boss whose days in power number back to the era of Huey Long. Marcello owns land not far from New Orleans that Jaffe has tried to buy. San Antonio police think that Fred sold some of his heroin to Marcello’s organization.

Morris Jaffe is also very close friends with the present mayor, Charles Becker. Becker is the scion of a wealthy family whose money comes from the Handy Andy chain of grocery stores. He has never really gotten along with police since his younger days when he used to like racing his sports car around the streets of the city. Jaffe had introduced Flores to Mayor Becker. The three of them, acting independently, decided they would investigate Fred’s charges.

But Fred wasn’t willing to produce his witness, the man who was supposed to implicate Ortiz and Weilbacher, without getting something in return. First he asked for safety for his family and for the witness’ family. When Flores agreed to that, Fred said that he would reveal the identity of the witness only after Flores had performed one more task. When Fred was in jail in Guadalajara his two remaining half-brothers were robbed by men who entered their homes flashing badges and claiming they were officers executing search warrants. They then proceeded to strip the two houses of all the money and drugs they could find. And they seemed to know just where to look for what they wanted, finding loot beneath stairwells and behind pipes. When Flores got a confession for those robberies from two addicts and police characters, Fred finally produced his witness, a 26-year-old narcotics peddler named Daniel Jaramillo.

Flores took Jaramillo to the mayor’s house where he told his story. He said he had been riding in a car with Ruiz and Castano when another car pulled up behind them. Suddenly a shot burst through the car and killed Ruiz who was sitting in the front seat. Castano, who was driving, jumped from the car; Jaramillo jumped out on the other side, leapt a wire fence and hid in the darkness. Castano was not so fortunate, according to the story; he was shot where he lay in the middle of the road. The mysterious car circled his body and its occupants pumped him full of bullets. Jaramillo said he heard the dying Castano shout two names: Weilbacher and Ortiz.

Unfortunately for Flores, Becker, and Jaffe, reporters from the Light, one of San Antonio’s two dailies, had gotten wind of the meeting and came to wait outside the mayor’s house for their story. The next morning, a Sunday, the Light ran a headline in red ink that said, “Witness Says Cops Killed 2.”

The story didn’t mention the names Jaramillo said he had heard, but by Monday everyone around the courthouse and in the police department knew who had been named. Ortiz was dazed by the news. But Weilbacher did not take kindly to being paraded publicly as a murderer.

The story had broken on a Sunday. Both the mayor and Flores had said the witness was in protective custody in a secret location. The investigation was proceeding, they said. The Light was calling for a swift resolution. All that lasted two days. On Tuesday Jaramillo, the secret witness, and five other men were arrested in a motel room with ten pounds of heroin. The investigation was suddenly at a halt. “Good God, that’s all we needed,” the mayor said when reporters told him about the arrest. Having composed himself, he described it as “a reversal of the highest order.” It turned out that the witness hadn’t been in protective custody at all. Since his name was never mentioned in the papers, Flores had decided to let him run free.

The same day Jaramillo was arrested, Weilbacher identified himself publicly as one of the officers mentioned, proclaimed his innocence, and said he would cooperate fully with any investigative body. The next day he stood in the same room with Jaramillo, who didn’t recognize him. The grand jury, after a two-week hearing, reported there was not a “scintilla of evidence” against the two officers. It was the right verdict, but one that while clearing Weilbacher and Ortiz would condemn Flores. After the smoke cleared both Weilbacher and Flores were reassigned duties. Flores is back in uniform performing essentially clerical tasks. Weilbacher, not quite as autonomous as he was, still prowls his old territory.

Becker and Jaffe continue as before. Their power is above such reversals.

When Ortiz and Conant walked into Gillespie’s office just before three, the citizen considered the stage set for the governor’s call. On hand would be Carrasco’s defender, his prosecutor, and one of the police who had captured him.

Conant, the prosecutor, walked to one of the few sections of wall that was not covered with Gillespie’s diplomas and opened the door of a hidden cabinet, reached for the bottle of bourbon, and poured it into a plastic champagne glass until the glass was full. Then he sat down in the chair across from Gillespie’s desk in the middle of the room, took a drink, set the glass on the edge of Gillespie’s desk and said, “I’m hurtin’. I’m really hurtin’.”

Conant is a big man. He has longish blond hair, a thick face, thick shoulders, a thick girth—an ex-football player now somewhat beyond his playing weight. Looking at Ortiz and Conant, if someone said one was a lawyer and one was a cop and asked you to name which was which, you would have said Conant was the cop.

“I’m really hurting,” he said again. “It’s as much my fault as anybody else’s that that son of a bitch is in Huntsville. Did you know that my sister-in-law, my own brother’s wife, the same last name as me, works in that library? The same last name as me, now. She was visiting her sick grandfather and he took a turn for the worse. She decided to stay an extra day. She works that same shift. If it wasn’t for her grandfather she would be in there with Fred right now.” He paused significantly, and held up one admonishing finger: “The same last name as me.” The whole idea galled Conant so much he took another slug of his bourbon. Then he turned to look at the citizen who was sitting with his arms resting straight out across the back of the sofa. No expression passed between them and, without any real pause, Conant turned back to Gillespie. The citizen could only assume that Conant wanted to gauge his reaction to that speech and perhaps check to see if he were taking notes or using a recorder. But it wasn’t until Conant finished that the citizen understood the reason for that pause. “I came that close,” he said, holding his thumb and forefinger a sliver of light apart, “to driving down to Huntsville and walking out in that courtyard in front of the library—armed—and calling Fred down.”

Gillespie began, “It’s a good thing you . . .”

“Maybe I’ll still do it. My very own name, now. Remember that.”

“Don’t go down there,” Gillespie said. “Fred is very fast. He would kill you.”

“Maybe he would,” Conant said. He took a drink and tilted his head like he was once again considering the possibilities. “Or maybe the others would get me after I got Fred.”

The citizen tried to watch all this with absolute calm. Except in a movie theater he had never heard anyone talk even half-seriously about a duel with guns.

But Conant suddenly changed the subject: “Jimmy,” he asked Gillespie, “where’s Rosa?”

“I don’t know. I don’t have any idea.”

That was the first hint of why Conant and Ortiz had come there in the first place. Officially at least, Rosa was not yet wanted for aiding Fred in getting the guns; officially, government planes were in wait to whisk her to Huntsville, where she might be of some use during the negotiations with Fred. In any event, they wanted Rosa and the trail had led to Gillespie since the car she was thought to be driving was registered to his law office. Evidently Carrasco had given Gillespie money to buy Rosa the car as a Christmas present. Gillespie had bought the car, registered it, and then Rosa had picked it up but never bothered to change the registration to her name. Ortiz and Conant asked some close, quick questions, returning now and then to ask the same question a second time, and in a few minutes were satisfied that Gillespie didn’t know where Rosa was. Three o’clock had long passed.

“Do you think anything’s happened?” someone asked.

“No,” Gillespie said. “They are supposed to call me immediately if anything happens.” Gillespie, in addition to the obvious strains and worries of the moment, was also annoyed that another attorney who had had some dealings with Carrasco, Ruben Montemayor, had arrived in Huntsville a few hours after Fred took over and was now acting as the conduit through which Carrasco and prison negotiators were speaking. Montemayor was thereby getting considerable publicity in the newspaper stories about the event. They generally labeled him “Carrasco’s attorney.” Montemayor’s publicity backfired somewhat when he volunteered to go to the library to talk with Fred. Fred’s answer to that suggestion was, “If he comes, I will kill him.” Gillespie hoped for that phone call with the governor not only because he was genuinely concerned about what might happen in Huntsville, but also because it would have been he, not Montemayor, who had done the negotiating when it really counted. Earlier he had instructed his secretary to “take Ruben off the list of people to call when I’m out of town.”

Since the three o’clock deadline was the third one Fred had let pass that day and since there had been no news at all from the prison, the immediate crisis apparently had subsided. Strangely, the release of that tension made the citizen feel a little like a hostage himself. There had been no phone call, no new information about Fred; and now he was stuck far from the door in an office filled with swirl and sputter and braggadocio.

Conant drained the last drops of his bourbon from the plastic champagne glass. He held it up empty. “You want some more?” Alonzo said, the devil in his eyes. “I’ll get you some more.”

“That’s exactly right,” Conant said. He handed the glass to Alonzo, who walked past him to the rear of the office where the concealed liquor cabinet was. “You should get me a drink the way I beat you in court. And I’ll say something else—” he looked around the room at everyone but Alonzo “—if he pees in that glass instead of pouring me bourbon, I’ll shoot him right on the spot and that’s a promise.” He held his arms outstretched, palms up, shrugging. “Now you’re all watching. Did he pee in my glass? No? All right then. I guess I won’t have to shoot him.” He forced a few chuckles as Alonzo, unruffled, handed the refilled glass back to him.

“I’m still thinking of going down to Huntsville,” Conant said. He pulled out a black gun that looked a little like a Luger with a thick long barrel. It was all black in his pudgy white hand.

Everybody looked at the gun which Conant proudly held. Then Gillespie pulled a .25 caliber pistol from a drawer in his desk and showed it to Conant and then Ortiz pulled out his silver revolver and began exhibiting it. A gaggle of technical data about each weapon filled the air.

It was so odd. At the same time Carrasco and two confederates were waving guns in the faces of their hostages in the prison library, three men in this lawyer’s office were waving guns in the air and boasting about who was fastest, the best shot, which gun was the most lethal. The citizen felt uncomfortable, less uncomfortable certainly than he would have felt in the prison library just then, but uncomfortable still as gun barrels from time to time were inadvertently pointed in his direction. A death in the prison library would be called a murder; a death in this office under these circumstances would be called an accident.

After a while, Conant and Ortiz left and then Alonzo left. Takas began regaling the citizen with funny stories which he acted out waving his arms and changing his voice. Gillespie nervously smoked. About 6:30 the phone rang. Gillespie answered. “Yes, sir, I’ll hold for the governor,” he said.

Takas and the citizen sat up straight. The citizen felt his palm turn clammy as he readied his pen.

“Yes, Governor, this is James Gillespie . . . Yes, sir . . . No, you may not kick me right in the ass, governor . . .”

Takas and the citizen looked at each other in confusion. Gillespie started laughing for the first time that day. It was Alonzo who was calling.

“Oh, God damn,” Takas said.

The citizen agreed: God damn.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Crime