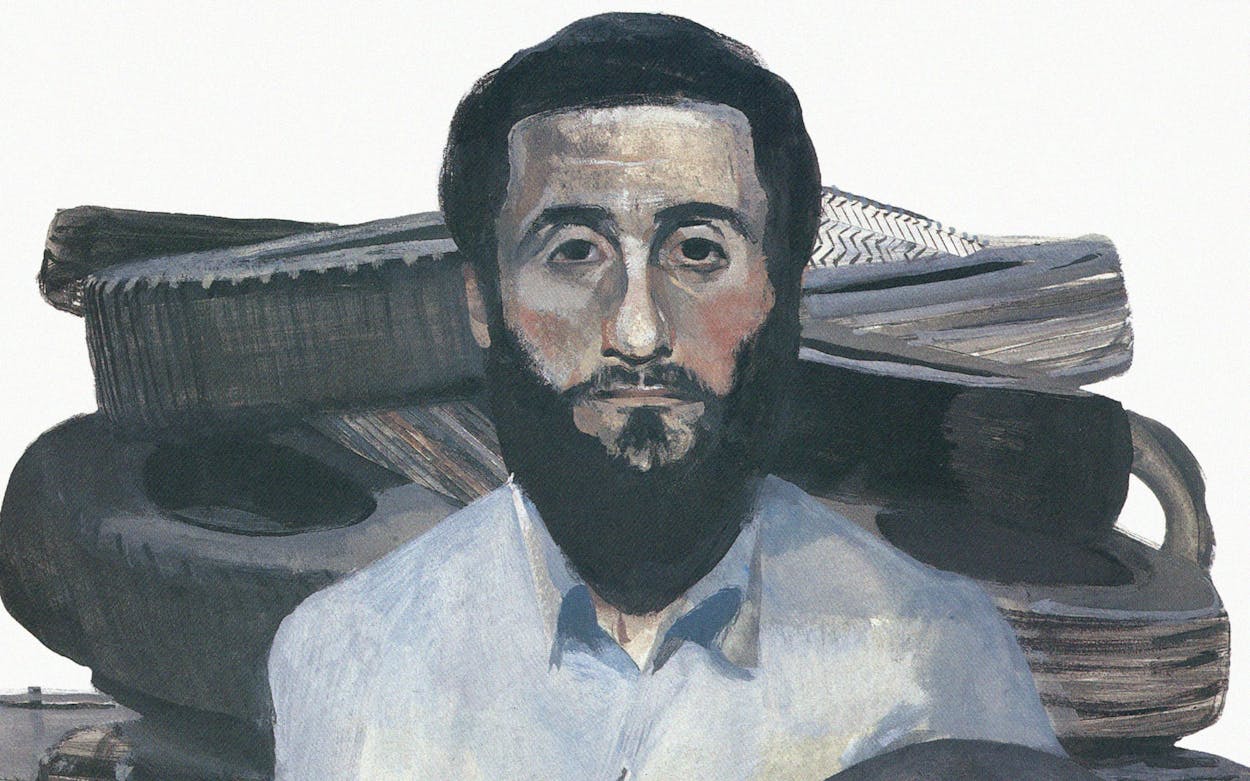

The small wood-frame building sits next to a seedy fifties motel on a forlorn stretch of Fort Worth’s East Lancaster Avenue, looking dilapidated despite a recent whitewash. Today it is home to a thrift shop stocked with goods that would appeal only to the poorest scavengers. That several years ago this building was the home of Lone Star Wheels and Tires seems, on its face, unremarkable; so too the fact that Lone Star went out of business after a relatively short run. East Lancaster is a haven for marginal enterprises that come and go, just like the immigrants who work there. But in one way, Lone Star was different from the others: Instead of Thais or Mexicans or Central Americans, it happened to be run by deeply religious Muslims from the Middle East. The average customer would have taken little notice of the slight, soft-spoken manager with the dark hair and eager smile except, perhaps, to marvel that he could change tires with a misshapen right arm. He was friendly, agreeable, not unhandsome—the kind of man a customer might thank for a job well done and forget about before he had pulled back into traffic.

Or maybe the man was sipping coffee at the Griddle down the street. The regulars rarely noticed him; he barely spoke to the coots who collected at the homey dive almost every morning. But sometimes he would issue a warning: something about the United States’ favoritism toward Israel, maybe, or the presence of U.S. troops in Saudi Arabia and that terrible things might happen if America didn’t change its policies. If the customers had paid attention, they might have noted the certainty in his eyes or the urgency of his words, but no one was paying attention. He was just another guy with an opinion, and the Griddle attracted a lot of those.

But there was something extraordinary about this seemingly ordinary man: Once, halfway across the world, he had been the personal secretary to Osama bin Laden. His name was Wadih el-Hage, but members of Al Qaeda also knew him as Abdul Sabbur, Abu al Sabbur, Wa ’da Norman, or sometimes just plain Norman. Before he was changing tires and sipping coffee and taking his seven American children to their Islamic school, he was using his American citizenship in the service of bin Laden’s business enterprises. According to law enforcement sources, he bought equipment—ships and planes, along with seeds and cement—and falsified passports and generally helped to grow the organization. As he moved from the U.S. to Pakistan and Africa and back again with his American-born family, he and his cohorts left behind a nearly invisible trail of associations and deaths.

And then his string ran out. One year after el-Hage returned with his family from Nairobi, Kenya, to Arlington, in August 1998, Al Qaeda operatives killed 213 men, women, and children in an explosion at the U.S. embassy in Nairobi. Soon after the bombing, federal prosecutors subpoenaed el-Hage to testify before a grand jury about his involvement; caught in lies, he was arrested for perjury, subsequently indicted for conspiring to kill Americans, and convicted of that crime. Just after the September 11 terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, he was sentenced to prison for life without the possibility of parole.

The men who attacked the World Trade Center and the Pentagon remain strangers to us—they were angry zealots with whom most Americans have nothing in common. But Wadih was one of us. He lived among us for years, received his education at an American university, took American citizenship, was loved by his American family, and was more grateful than the average American for the myriad freedoms extended to him. “He always put Islam first,” his mother-in-law, Marion Brown, told me. Yet, as his faith deepened, his resentment of this country grew; he embraced the privileges of being an American but not the obligations.

In doing so, Wadih el-Hage became the traitor next door, and no one knew a thing—until it was too late.

The Convert

In the wake of September 11, much was written about the emergence of a new, highly toxic strain of anti-Americanism, one born not in the hopeless villages of the Middle East but within comfortable middle-class families, where devout, educated young Muslims were outraged by the corrupt, secularized regimes propped up by the American government. This was Wadih’s story—with one significant variation: His family was Christian.

Born in 1960 to a Catholic family in Lebanon, he was much loved, the only son and the eldest of three children. But at Wadih’s birth, the doctors had mangled his right arm while trying to remove him from the womb with forceps, an injury that set him apart early. He grew up more thoughtful and observant but also more desirous of fitting in.

His family was westernized in a country that took pride in being the progressive jewel of the Middle East. Wadih’s father was an engineer who worked for an American oil company; the family went to American movies and watched American television programs. Wadih’s favorite was Little House on the Prairie. His future must have seemed assured: He would enjoy the prestige of an American education and return to take a prestigious place in a country run by people of his own Christian faith.

But then Lebanon was riven by a religious-based civil war, and the oppressed Muslim majority was willing to level the country to gain control of the Christian-dominated government. The family, which had divided their time between Lebanon and Kuwait, settled permanently in the latter. In Kuwait, however, Christians were in the minority, and as Wadih grew up, he was drawn to Islam. He must have resisted at first; the hatred between Muslims and Christians was centuries old and to switch sides would shame his family deeply.

Whether from peer pressure, youthful rebellion, or true belief, Wadih finally converted in secret, at age fourteen. He wanted to do good, and Islamic fundamentalism had an answer for every question and strict guidelines for virtuous behavior. He was an outsider no longer; as a Muslim among Muslims, Wadih was instantly accepted. Or rather, he was accepted everywhere but at home: When Wadih hinted about converting, his father, furious, chased him around the house with a knife. And when Wadih’s father learned the truth, he cut his son out of his life. He was a traitor to his family.

Wadih left the Middle East and headed for the University of Southwestern Louisiana, as planned. But with two part-time jobs, he could only afford to take two classes. His hopes for an American education evaporated. That is, until a holy man in Kuwait heard of his plight and, as faith dictated, offered financial help. To an impressionable eighteen-year-old, the mentor’s grace would have appeared nothing less than providential; Wadih’s journey of secrecy, rebellion, and redemption would shape the rest of his life.

The Invisible Man

The USL campus, in Lafayette, was oak-shaded and intimate, but it was provincial too. To most white USL students in 1978, all the foreigners from the Middle East looked alike. Wadih was, to them, invisible.

But they were not invisible to him. To Wadih, Lafayette was replete with riches, temptations, and of course, inequities. The jobs open to him were the same marginal jobs open to poor Americans—he worked at Burger King and Tastee Donuts and gained weight as he gorged on sweets. In class he studied urban planning. In his free hours he was offered a curriculum of life on the fringes: how to get by in the U.S. without attracting notice.

But mostly, Wadih prayed. Free of his father’s disapproval, he rejoiced in practicing his religion openly. A less dedicated young man might have drifted away from his faith, dating American girls and eating pepperoni pizza. But Wadih persevered with a convert’s zeal, using Islamic fundamentalism as a shield against Western temptations and his own loneliness.

Wadih eventually became a leader in Muslim youth groups, in which a nascent anti-Americanism had already taken hold. The preface to the constitution of the Muslim Arab Youth Association, for instance, stated, “In the heart of America, in the depths of corruption and ruin and moral deprivation, an elite of Muslim youth is holding fast to the teachings of Allah.” Wadih was moving into conflict with his adopted country: He loved the U.S. for the personal freedom that allowed him to be a Muslim without fear, but he loathed the secular, often profane consequences of that freedom.

Then, in 1979, the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan. To the Islamic world, a godless country was despoiling a Muslim paradise, and the loose associations on college campuses quickly constellated into an intelligence-gathering, recruiting, and fundraising network. But Wadih felt compelled to do more. Stirred by the call to jihad, he abandoned his hard-won education and moved to Peshawar, Pakistan, a dusty, mountainous border city that had become the staging area of the mujahideen, the Islamic guerrilla fighters in Afghanistan. He couldn’t fight because of his arm, but that only deepened his conviction: Every day, he distributed Korans in hospitals and refugee camps.

In Pakistan Wadih also came under the influence of a new mentor, Sheik Abdullah Azzam, a stocky, bearded, hyperbolic Palestinian who believed feverishly in the restoration of Islamic glory. Focused entirely on finding allies intent on beating the Russians, the U.S. overlooked—or Azzam concealed—his virulently anti-Western feelings and his propensity for violence, which he linked directly to the Koran. “Every Muslim on earth should unsheathe his sword and fight to liberate Palestine,” he urged in one speech. “The jihad is not limited to Afghanistan. . . . Jihad means fighting. . . . It does not mean to fight with the pen or to write books or articles in the press or to fight by holding lectures.” For Wadih, Azzam’s exhortations would forever link war with Islam’s survival. He experienced, in essence, a second conversion.

Wadih returned to school in Louisiana in 1984, a 24-year-old Islamic militant. Emboldened, he wrote letters home to his father, complaining about American arrogance in the Middle East. He received in reply a warning to keep his opinions to himself. Wadih responded like any American. “This is the U.S.,” he wrote. “You can say whatever you want.”

Love and War

When Wadih el-Hage met the family of his future bride he must have been stunned at his good fortune: They were Americans, but they were also all devout Muslims. He had found his fiancée through the budding Islamic-American grapevine—an imam in Tucson had put out the word that April Brightsky Ray was available for marriage proposals, and Wadih had written to her mother, Marion Brown, for permission to meet. His bride to be was just eighteen; sweet and accommodating, she was a soft, round, moonfaced girl with an infectious giggle. In school, April had played the trumpet with abandon, a single sign of impetuousness. Like Wadih, Marion was a convert to Islam. She found him eager to please—”a good boy.” His letter read more like a job application than a proposal, with his goal being “to live life according to the Koran.”

Because Wadih was not from America, he failed to recognize the particular type of Westerners he was dealing with. April’s was not the West of American promise—of the movies Wadih had loved as a child—but the West of last hopes. Marion, a scrappy, weathered woman, had come to the Muslim faith by way of several others—Judaism, Buddhism, and Protestantism. She could trace her ancestors back to seventeenth-century Salem, Massachusetts, but her own life had been a rocky journey from man to man and cause to cause; she had had five husbands and ten children. April was unformed, impressionable, with no father figure in her life. Her fiancé appeared absolute and steady, sure of himself and his cause. Safe.

Or so it appeared. After the wedding, Wadih took her back to Louisiana so he could finish school. In a tiny apartment near campus, April kept house and learned to cook. She complained to her eldest brother about Wadih’s unexplained absences, but she was only eighteen, and good Muslim wives were obedient and unquestioning, so she went along. Besides, Wadih had the power to lift her spirits with a single, silly gesture: One night he caught her parked in front of the television, bored, watching the Miss America pageant. He jumped in front of the screen, a slight man wearing the broadest smile, his eyes dancing as he flexed his muscles, inserting himself into the picture. At such moments he was not a stranger but someone she could love, fully and desperately.

Wadih’s commitment to jihad galvanized his new family, who saw in his zeal something lacking in their own histories. When he moved back to Pakistan in 1986, he took not only April but also Marion and her husband, all at Abdullah Azzam’s expense. The el-Hage home in Quetta was always full of people, partly because of a Muslim tradition that dictates hospitality to fellow Muslims and partly because Wadih naturally welcomed all comers. “He was like Will Rogers,” Marion said. “He never met a man he didn’t like.” A cardiac intensive-care nurse, she worked in a hospital while her husband fought against the Russians. “The Russians bombed the houses, and when people ran out, they’d shoot them,” she told me. “The Afghanis loved the Americans. Everyone wanted to come to America.” When April gave birth to their first child, she and Wadih made a pilgrimage to the U.S. embassy in Islamabad to register him as an American citizen.

Even so, life in Pakistan could be difficult for an American family, even one deeply committed to Islam. Marion and Wadih argued over her place in a society that believed women should be hidden behind the veil, and she departed. Soon April’s life was punctuated once more by Wadih’s absences. She understood that Wadih was crossing into Afghanistan to do some kind of relief work for Azzam’s Office of Services for the Mujahideen, an organization for the Islamic resistance and their families, but his explanations were vague. He carried a pistol, and she was often frightened that he would not return.

Wild, Wild West

Wadih and April tried to balance their faith with their financial survival. For a year they stayed near the fighting, until according to April, “we had no choice but to leave. When we ran out of money, we went home.” That meant Tucson, whose harsh, imposing mountains, scrubby desert, clear skies, and cool summer nights were all reminders that it shared a latitude with southern Afghanistan. April’s family was there, and the city also had a growing Muslim community. Wadih, now a father of two, worked for the city as a janitor without complaint. “Allah says that all work is valued,” April explained to me. But just because he worked for an American government in an American city did not mean that Wadih was assimilating. Instead, he built a Muslim world within his American world and retreated into it. He was active in his local mosque, and he raised his children in strict accordance with Islamic law. April’s siblings began to avoid her, weary of lectures about their lack of faith. For her own children, there were no birthday parties and no holiday feasts other than the two major Islamic celebrations.

In fact, Wadih made only one crucial concession to his adopted country: In 1989 he became an American citizen. “He had so many reasons for wanting to be an American,” April told me, slightly at a loss for specifics. “As many reasons as you can think of. He could practice his religion openly.”

But halfway around the world, other factors may have affected his choice. The same year Wadih became a citizen, the Soviets retreated from Afghanistan. The mujahideen—young, armed, fearless—were not inclined to stop fighting; they turned on the holdover government in Kabul and on each other. Abdullah Azzam turned on a different enemy: America, a country he saw as inhabited by shallow, pleasure-seeking infidels who supported corrupt, secular regimes in the Islamic world. But before he could take action, he was assassinated by a car bomb in Pakistan, and his organization was absorbed by another group—Al Qaeda, led by another Azzam protégé, Osama bin Laden.

The heir to a seemingly unlimited Saudi fortune, bin Laden launched an immediate expansion campaign, opening training camps and stockpiling weapons. He also began recruiting Afghan war veterans with American passports, who could travel the world without arousing the suspicions of law enforcement. Wadih, of course, was the perfect candidate. In fact, it was around this time that he became a sort of Zelig-like figure in the burgeoning world of international terrorism—never directly linked to violent acts but often nearby.

According to terrorism expert Steven Emerson, the author of American Jihad, Tucson had become home to the first Al Qaeda cell in the U.S. It was in Tucson that Azzam’s old Office of Services opened its first American branch, now renamed the Alkhifa Center. Many figures associated with radical Islamic organizations passed through town: Two plotters of the 1993 World Trade Center bombing would be linked to the Al Bunyan Islamic Information Center in Tucson, as was Wadih, who had reporter’s credentials from the organization’s publication. The Islamic Association for Palestine, a group with links to Hamas, had an office in Tucson too. In those days, Wadih had access to an AK-47; he told the authorities he used it for hunting.

One day, in 1990, a stranger with a long beard and eyeglasses appeared at Wadih’s home. He asked many questions about a local imam named Rashid Khalifa, a liberal Muslim cleric who was considered a heretic because he allowed men and women to pray together in his mosque. Wadih would later tell a grand jury that he fed his visitor lunch and drove him to the mosque, where the man observed services. Soon after, Khalifa was murdered by a member of a black Muslim fundamentalist group who would later be linked to the first World Trade Center bombing. Wadih was never tied to the crime, though authorities would later question him about why he never reported the visit to the police. It didn’t occur to him to do so, he said.

Violence followed Wadih when he moved with his family to Arlington, where one of April’s brothers lived, a year or so later. He had trouble finding work and began brokering the sale of used cars to the Middle East to support his family. An old friend called, looking for a favor; it was Mahmud Abouhalima, another veteran of the Afghan war. He asked Wadih to buy him a few weapons—two Seminov rifles and an AK-47. Wadih bought the guns from April’s eldest brother, a sometime gun dealer who had also served in U.S. military intelligence. Abouhalima never picked them up. Eventually he would be convicted of conspiracy in the 1993 World Trade Center bombing.

Then, in 1991, a friend asked Wadih to move to New York to run the Brooklyn branch of Alkhifa. Wadih agreed, but when he arrived in New York, violence had preceded him: The friend was dead, murdered in a crime that remains unsolved. Wadih wept when he gave April the news, but before returning home, he took the time to visit a man named El-Sayeed Nosair in jail. Nosair was being held for the murder of radical Jewish rabbi Meir Kahane.

As supportive as Marion Brown was of her son-in-law, she was becoming uneasy. She mentioned to one of April’s brothers that she had heard a group of Wadih’s friends talking about hijacking an airplane. On another occasion, the brother heard Marion address Wadih as Abdul Sabbur. “Who’s that?” he asked. Wadih turned ashen and immediately changed the subject.

Soon after, he accepted a job offer overseas. His employer: Osama bin Laden.

Bin Laden’s Man

Wadih el-Hage and Osama bin Laden had a lot in common. Close in age, they had made similar, profound sacrifices for the same cause; their allegiance to Islam had forced them into exile from their families, and that loss fueled their titanic zeal for jihad. But bin Laden, from a family of rich, cultured Saudis, was a gifted, charismatic manipulator, while Wadih was a follower. Wadih’s pacific mien made him, in fact, a perfect front man for bin Laden’s deadly goals. “Wadih is a person who, once he has made a decision, obligates himself,” one of his lawyers told me. Service to Al Qaeda and service to Islam were one in the master’s mind, so every order to Wadih became a matter of his loyalty to not just bin Laden but also Allah.

The two probably had met in Peshawar, where both had worked with Azzam. But while Wadih was in the U.S., struggling to make ends meet, bin Laden, with unlimited funds, was building Al Qaeda. Like any CEO, he needed a secretary he could trust implicitly; Wadih’s loyalty, discretion, and history made him a perfect candidate, and even better, as an American citizen, he would not be suspected of terrorism. According to April, Wadih went to the Sudan for a job interview and returned to tell her to start packing. “He seems fair,” Wadih said of bin Laden. “Let’s do it.” Bin Laden offered Wadih $1,200 a month—a king’s ransom in the Sudan.

The Sudan in 1992 was a terrorist’s paradise. Ruled by an Islamic fundamentalist regime, its government gave Al Qaeda favored status among several terrorist newcomers; it was bin Laden’s money and bin Laden’s companies that contributed to the construction of much of the country’s infrastructure. The government reciprocated by allowing bin Laden to build training camps, smuggle in weapons, and establish charities—fronts—with impunity. He traveled through the streets of Khartoum in a shimmering black Land Cruiser with tinted windows.

The old army was reforming, invisibly, against a powerful but oblivious enemy in the West. Wadih was reunited with men with whom he had shared the most meaningful days of his life. The lowly U.S. janitor now ascended to a job that was the jihad equivalent of vice president of corporate development. Wadih’s office sat just outside bin Laden’s at a tasteful compound in Khartoum. When he wasn’t drafting letters or controlling access to the boss, Wadih was circling the globe, searching for markets for the Sudan’s corn and sesame seeds, and buying asphalt for new construction. Other bin Laden associates had different sorts of assignments: One scoured the world for uranium, the critical component of nuclear weapons.

Working for Al Qaeda was in some ways like working for any underfunded organization with a demanding boss. Bin Laden was full of ideas: once he had wanted to set up Wadih’s father-in-law in the aromatic oil business in the U.S.; now he wanted Wadih to buy him an airplane to transport Stinger missiles from Afghanistan to the Sudan. Wadih found one with the help of his contacts in the U.S., a pilot he’d known in Louisiana and the imam of his mosque in Arlington, who was once an aviation expert. Wadih would never refuse bin Laden, who, he liked to say, had the ability to make the world live according to the Koran.

Echoes of Loneliness

Even so, life in the Sudan became increasingly problematic. Wadih was not a natural businessman—everyone took advantage of him, according to his mother-in-law—and April, like many corporate wives, was souring on the demands placed on her husband. Khartoum wasn’t Tucson or, for that matter, Peshawar. Primitive and isolated, its rains turned the roads to muddy, impassable lakes of red clay, and the sandstorms exacerbated her asthma. And then there was the Al Qaeda boys’ club. One night Wadih came home to face the prototypical angry spouse demanding an answer to the universal question: “Where have you been?” Wadih wouldn’t meet her eyes. “What would you say if I told you I got married?” he said.

It had been bin Laden’s idea. There were so many widows in the Sudan, Wadih explained, parroting the boss. For once, April would have none of it. She reminded Wadih that their marriage contract prohibited him from taking another spouse. Like any shrewd American wife, she threatened divorce. The second marriage was dissolved. “I could not have handled my own jealousy,” April said.

In 1994 the family moved to Nairobi. Family members say Wadih was trying to break with bin Laden, but intelligence sources believe that he was simply transferred to Kenya after another operative attracted too much attention from the local police. In Nairobi Wadih tried to establish himself as an international gem dealer—Why don’t you just sell them on eBay? his mother-in-law wanted to know—and as the head of a charity with the obtuse name of Help Africa People.

By then Al Qaeda’s violence was intensifying. Following attacks on U.S. soldiers in Somalia in 1993, the Sudanese government, under pressure from Washington, expelled bin Laden from the country in 1996. That same year, from his new home in Afghanistan, he declared war on America, though he limited his death threats to military personnel occupying Saudi Arabia. “[T]he main disease and the cause of the affliction is the occupying U.S. enemy, so efforts should be pooled to kill him, fight him, destroy him,” he wrote in one of his increasingly frequent fatwas.

Wadih was getting in deep. An Al Qaeda document written in February 1997 describes him returning from a trip to Afghanistan with instructions to begin military operations in East Africa. Wadih had traveled there with a top Al Qaeda official—bin Laden’s military commander, Muhammad Atef—who was killed by U.S. bombs in Afghanistan last fall. As bin Laden became ever more vocal in his criticism of the U.S., one of Wadih’s associates in Nairobi fired off a frantic missive: “. . . there is an American-Kenyan-Egyptian intelligence activity in Nairobi working to identify the locations and the people who are dealing with the sheikh [bin Laden] . . . I am 100 percent sure that the telephone is tapped after Wadi’s [sic] wife told me that . . . she heard strange voices in the television when she was trying to adjust the speaker.”

Wadih was troubled. His business correspondence from that time remained cheerful and resolute (“Peace be upon you, and God’s blessings and mercy”), but entries in his journals, written in English, grew uncharacteristically bleak, as if he was torn between two choices, or two worlds. “[E]veryone will encounter pain whether he believes or not, except that the believers will encounter pain in this life only but will be rewarded in this life and the next,” noted a religious essay on jihad. “[N]on-believers will feel the pleasure in this life but will end up with everlasting pain.” Something continued to haunt him in a poem that appears a few pages later:

The children are sleeping and quiet is the night

Alone I sit in the dim light

Echoes of loneliness are all I hear

Thinking and waiting, I look towards the door

Hoping for a visitor but no one once more.

Sleepy and tired I walk to my room

Perhaps tomorrow someone will break through my gloom

Echoes of loneliness linger through the night

Tossing and turning from side to side

Sleep comes, long after I’ve cried.

Ten Green Papers

As U.S. intelligence officials realized that they were engaged in a desperate game of catch-up against well-funded, highly organized terrorists, the name Wadih el-Hage began to turn up routinely. He was linked with a participant in the World Trade Center bombing in 1993 and in Al Qaeda’s attack on U.S. soldiers in Somalia that same year—and, of course, he had worked for bin Laden. The agents tapped Wadih’s phone and recorded conversations that were often coded. Once he called April and asked her to send “ten green papers, okay?”

April: Ten red papers?

Wadih: Green.

April: You mean money.

Wadih: [sarcastically] Thank you very much.

April: [laughing] That’s only for you. Nobody else is listening.

Wadih: Okay, you don’t know that.

What Wadih didn’t suspect was that the feds hoped he might become a double agent. He was an American citizen, with an American wife and American children, and he had himself been nonviolent, all of which suggested to U.S. intelligence—still ignorant in the ways of radical Islamic fundamentalism—that he might be a willing convert.

In 1997 several investigators from U.S. and Kenyan intelligence burst into Wadih’s house in Nairobi, claiming to be looking for stolen property. Wadih was gone—away on business again—but April was there, as was Marion, the children, and another couple who had been living with them. Agents pored over the papers and notebooks that Wadih had stacked, willy-nilly, throughout the place. They packed up a computer and then gave April a warning: Nairobi wasn’t safe for them anymore. Wadih could be killed at any time. Would she like to leave immediately? No, April told them. She would not leave without her husband.

When Wadih returned and learned of the search, he was, in Marion’s words, “frightened and intimidated.” In a panic, the family sold everything they owned to raise the money for airfare back to the U.S. But if Wadih thought he would be safe in America, he was quickly proven wrong. After a 24-hour trip to New York, Wadih and his family were met at the airport by federal agents wielding subpoenas to appear before a grand jury investigating bin Laden and his associates. Prosecutors interrogated him late into the night and brought him before the grand jury the next morning. If he lied, they warned him, he could go to prison and never see his family again.

He was faced with a critical choice: his family and his country or Al Qaeda and jihad. Whether out of loyalty to old friends or fear of retaliation or his belief that his American citizenship would protect him, Wadih claimed to have known bin Laden only briefly and testified that the rest of the men the prosecutors mentioned to him were strangers. He didn’t know about any operations in Africa. He denied writing a letter to a man named Ali Mohammed, who, it was determined, performed surveillance for the Nairobi embassy bombing and is now in prison for life.

The prosecutor asked Wadih whether he recognized the handwriting on the letter.

“Very close to mine,” he allowed.

“Very close to yours?” the prosecutor responded.

“Yes.”

“Could it be yours?”

“I don’t think so.”

The prosecutor tried again. “Have you ever seen handwriting that close to your handwriting in your entire life on a letter you did not write?”

“I have.”

“Who writes like that besides you?”

“I don’t know who it is, but I have seen handwriting very close to mine.”

Wadih had made his choice. He completed his testimony and was allowed to go free.

Texas Is Wow

He settled with his family back in Arlington, which by the late nineties made for a perfect refuge. A faceless, sprawling suburb of malls, theme parks, chain restaurants, and hotels, it also had an international airport in the area that made coming and going easy. “I love Texas. Texas is wow,” April told me. “It’s out there. The people are wonderful. It’s beautiful. We both wanted Texas.” Then too Arlington now boasted a substantial Muslim population. Old friends quickly came to the rescue of Wadih and his family. The imam of the mosque introduced Wadih to the owner of Lone Star Wheels and Tires, a Palestinian immigrant who had once been a pilot in Pakistan. (The tire business was then a favorite of immigrant Muslims; it didn’t require much starting capital—$10,000, compared with at least $50,000 for a convenience store—and workers didn’t have to sell pork or alcohol.) Wadih became the manager at a salary of $400 a week.

The Center Street Mosque, where Wadih had worshiped before, remained as rigid in practice as it had been when jihad fighters had recruited there during the Afghan war. The women still covered themselves from head to toe in hijabs and were separated from men at prayer. The modern world was scorned: When a guest speaker showed up in Western dress, he was driven from the podium.

But then events conspired to destroy the peace and anonymity Wadih had found for himself. In 1998 bin Laden issued a new fatwa. “We believe the biggest thieves in the world are Americans and the biggest terrorists on earth are the Americans,” he declared. “The only way for us to defend . . . these assaults is by using similar means. We do not differentiate between those dressed in military uniforms and civilians.”

On August 7 of that year bin Laden made good on his threat. At around ten-forty on a Friday morning in Nairobi, rush hour was still in effect. A school bus loaded with children jockeyed for space between honking cars and diesel-belching trucks. Then, suddenly, one truck swerved into the rear of the American embassy; within seconds, the building exploded in a ball of fire, and 213 men, women, and children were killed. Thousands more were injured, many blinded by flying glass. At almost the same time, another bomb exploded at the American embassy in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, where 11 people were killed.

Within a day, the FBI was knocking on the door of Wadih el-Hage. His world, once so big and so free, closed in around him.

Setting the Trap

In the eyes of the authorities, Wadih was no longer a bit player in a shadowy web of international terror; he was a suspect with links to a specific crime. Interviewed in his small apartment near UT-Arlington by FBI agent Rob Miranda while his children watched cartoons, Wadih told Miranda that, yes, he had worked for bin Laden, but no, he didn’t know how to find him now. He knew no one associated with the embassy bombings but doubted bin Laden would have been involved. He confessed only this: that any true-believing Muslim would want to drive the U.S. out of the Arabian Peninsula. By the end of that session, he had warmed toward Miranda. Maybe, he suggested, the two could meet again to discuss the Koran.

But a month later, in September, prosecutors summoned Wadih back to New York to testify before a grand jury investigating the embassy bombings. By then agents had thoroughly evaluated the contents of Wadih’s computer and had reviewed a trove of documents that had been stashed in the office of his Help Africa People charity in Nairobi. Many papers supported Wadih’s assertion that he was a legitimate businessman, but agents also found cryptic messages suggesting something sinister. There were, for instance, allusions to a Dr. Atef (the same name as bin Laden’s military commander) and a document titled “Report on the Latest News in Somalia,” which mentioned Wadih and militarizing an east African cell.

Prosecutors still had no evidence directly linking Wadih to the plot, but they began to pressure his associates, particularly the imam of Wadih’s mosque, and they accumulated bits and pieces of information that would prove to be valuable. Wadih was asked whether he knew a man named Mohamed Odeh, a prime suspect in the bombing; when he denied it, prosecutors produced witnesses who swore Wadih had been at his wedding. Wadih denied using various aliases, like Abdel Sabbur, but the grand jury had documents that clearly proved Wadih and Sabbur were one and the same. The government asked him questions that they had asked him in front of the first grand jury, and Wadih gave inconsistent answers. Immediately thereafter, Wadih was arrested and charged with thirty counts of perjury, each carrying a five-year sentence. One month later he was indicted for conspiring to kill American nationals.

Wadih was imprisoned without bail and, for the most part, denied visitors, except for a few visits by his wife and children. (Previously, Kahane’s murderer had continued to direct terrorist activities from his jail cell.) “The extraordinary limitations on his ability to communicate I had never seen before,” one of Wadih’s lawyers, Sam Schmidt, told me. For a while, Wadih accepted his situation. He read the Koran and tried to comfort his family. “Leaders have to be tested,” he wrote his mother-in-law.

But after a year in solitary confinement, Wadih’s optimism faded. His life had been reduced to a small, exposed cell; guards watched him shower and use the toilet on 24-hour surveillance cameras. He had been allowed only three visits from his family. Wadih became obsessed with his treatment—he punched walls, developed boils. And his letters home, once affectionate and teasing, became tyrannical. His concentration faltered too. He told a Harvard psychiatrist who was hired by his attorneys, “Now I try to pray, but I just start thinking and I get lost and I forget the praying.” Once, during a hearing, he disrupted court by leaping from his seat and attempting to flee. He could not believe that he, an American citizen, could be treated as he had been. “They keep treating you like an animal until finally you become like an animal,” Wadih told his doctor, “and then they have their justification for everything they’ve done to you.”

The Last Word

By the time Wadih’s trial started, in March 2001, investigators still had little tying him directly to the bombings. It was a little like a Mafia trial—the defense could show that he was a legitimate businessman, while the prosecution had to prove that his legitimate activities were merely a front for evil enterprises. The government had no letters from Wadih ordering the bombing, no explosives in his storage room, no declarations of jihad against the U.S. with his signature. One member of the prosecution’s team, admitted as much to the jury. “No, we are not going to present any evidence that [Wadih el-Hage] wired any bombs, that he offered any training, that he received any training, but that doesn’t make him not in this conspiracy,” he told the courtroom. “On the contrary. What the evidence shows is that he provides an essential role for Al Qaeda.” The prosecutor insisted that Wadih was a “facilitator,” the man who arranged fake passports, built phony businesses, and kept coded records that allowed the plot to proceed.

But even without firm evidence, Wadih was vulnerable. The jury knew he was charged with lying to the FBI and two grand juries. And, thanks to maneuvering by the prosecution, he was tried with three men who had either made or delivered the bombs that blew up the embassies—two of his co-defendants, in fact, had confessed to their crimes. Wadih appeared in full Islamic dress at the trial, his beard unclipped and his hair long, a sign of defiance.

His great loyalty to old friends was not repaid in kind, as several testified against him. They talked about his purchase of the plane for bin Laden; they recalled his close association with military strategist Atef; they recalled him weeping at the news of the death of a military leader he had told the grand jury he had never met. The prosecutors showed the jury his notebooks with their coded entries and introduced a so-called “terrorist cookbook” that contained recipes for killing on a mass scale that belonged to Wadih’s former housemate, an indicted fugitive in the Nairobi bombing. A fingerprint expert testified that Wadih’s prints were on letters to an Al Qaeda associate that, in grand jury hearings, he had denied writing. That evidence, combined with the horror of the crime, sealed Wadih’s fate.

To everyone but himself, that is. His sentencing took place October 18, 2001, when the country was still reeling from the devastating attacks of September 11 that had occurred just blocks from the courtroom. Given the chance to speak, Wadih spoke in a soft voice of God and Islam and the “selfish and deceitful rulers” of the Middle East. But, even after September 11, he could not stop himself from repeating the lecture he had given so many times before. He said he was appalled by the bombings in Africa, which violated his teachings as a devout Muslim. “[B]ut please understand that my beliefs form my opinion that many American policies toward Muslim countries and people are wrong,” he added. The American sanctions on Iraq, the U.S.’s unconditional support of Israel—these events had led his world to turn on ours. “There is nothing wrong or shameful that I did to apologize for,” Wadih said, “and I hope that one day the truth will come out clear.”

The speech so outraged prosecutor Patrick Fitzgerald that he asked permission to make an unprecedented rebuttal, and the judge allowed it. Mr. el-Hage, he said, “has talked today about choice, and I think one thing we should remember about choice is, Mr. el-Hage made a lot of choices. . . . he chose to go with those who would kill rather than to help himself, his family, his country. He claims to be a citizen, but he is not an American. He claims to be a religious man, but he is not a true Muslim. The true Americans, the true Muslims, the true family men, . . . those are the people he helped to kill. . . . he betrayed his country, he betrayed his religion, he betrayed humanity by his behavior for so many years.”

Wadih showed no reaction. Sam Schmidt told me, “He wouldn’t see himself as the government saw him.”

Invisible Again

Wadih el-Hage now resides in solitary confinement in a maximum-security prison in Florence, Colorado, where he will remain for the rest of his life. To most Americans, he is, once again, invisible. Only a few people, like his mother-in-law, still insist that he was not a conspirator, just a dupe—a ne’er-do-well in business, physically unable to take up arms, who did the bidding of others because he was told Islam demanded it and never really knew what the ultimate plot was. “Wadih was too trusting,” Marion told me. “And people took advantage of him.” April el-Hage has no such doubts. Her faith in her husband is unshakable. Wadih, she insisted, would never kill innocents because it would violate the Koran. Besides, she continued, he would never betray the United States. “My children and I are American,” she said. To commit the crime for which he is imprisoned, “He would have to hate himself.”

Her husband’s acts have plunged her own life, and that of their children, into chaos and poverty, but at 35 she is still spunky and defiant, a bustling woman who wears spotless white running shoes with her traditional head scarf and robe. We met in a hotel room near Six Flags because she is constantly in hiding, moving frequently, changing her cell phone number, and chasing reporters away from her garbage. She and her children live on handouts from the mosque.

A Newsweek cover story she thought might help Wadih’s appeal backfired. The editors put her face on the cover with the line “Married to Al Qaeda,” which she calls a misrepresentation. “I am not a bride of Al Qaeda. I’m not married to Al Qaeda. Even the government was never able to prove that [Wadih] was a member of Al Qaeda,” she told me.

Their war, she says, was the one she and Wadih fought decades ago, in Afghanistan, for Islam. “That was a U.S.-backed war,” she said. “The U.S. encouraged and supported it. They said it was totally legitimate for us Muslims to go there.” And then April paused, and her gay eyes went dark and steely. “I didn’t see the memo about when we were supposed to stop, did you?”

- More About:

- Arlington