This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

In 1793 two giants of Texas history—Sam Houston and Stephen F. Austin—were born in Virginia. Yet while the bicentennial of Houston’s birth has been celebrated this year in books, memorials, ceremonies, and pilgrimages, Austin’s has gone largely unnoticed. Why does Houston seize our imagination and attention when most Texans don’t even know what Austin’s middle initial stands for?

The reason is that Houston was a hero on horseback who blazed bigger than life across the public stage; Austin was an unassuming builder and civilizer. Both were essential to the emergence of Texas, but posterity, like life, isn’t always fair. It’s easier to remember and extol warriors than businessmen.

Everyone grants Austin the title of Father of Texas, but the epithet somehow doesn’t do him full justice. He did more than simply sire Texas; he nurtured it, protected it from harm, and raised it through a cocky adolescence to the point where it could survive without him. Sam Houston could have achieved nothing had not Austin gone before him. Anglo Texas really was Austin’s creation. He was the greatest and best empresario of his day: against all odds, he realized the dream of his father, Moses Austin, and settled Anglo Americans in the province of Texas. He then defended and increased his colony through a bewildering and byzantine succession of Spanish-Mexican royalists, imperialists, republicans, and dictators.

It still seems incredible that Austin accomplished all of this in such a short life—he died at age 43. On the one hand, he had to contend with Mexican regimes that rarely trusted him and never helped him while at the same time dealing generously and wisely with the horde of Anglo immigrants placed under his jurisdiction. On the other hand, he had to placate his colonists: law-abiding, hardworking, self-reliant families who also tended to be prejudiced, stubborn, jealous of every right, ignorant of the politics of their situation, and suspicious of all authority, including his.

From 1822 to 1830, Austin was lawgiver, military commandant, banker, land-granter, and official greeter of every American who settled between the Brazos and the Colorado. In those years he located more than a thousand substantial families in Texas and carved out its heartland. His people felled more trees, cleared more ground, raised more crops, had more children, and built more towns than the Spanish did in three hundred years of colonial rule. He was the greatest proprietor of his kind in North American history. These efforts and accomplishments can hardly be exaggerated. Although he never became rich—he began as a would-be capitalist and developer but somehow turned into a mere visionary—he was easily the greatest and finest of the men who received grants to settle foreigners in Texas. He was the only one who saw his role as more than selling and speculating in land.

Austin first came to Texas to make money, but soon he was obsessed with a goal to redeem it “from its wilderness state by means of the plow alone; in spreading over it North American population, enterprise, and intelligence.” He had no aim of separating Texas from Mexico; he remained loyal to whatever regime ruled it until he was at last forced into rebellion by arbitrary government.

Don Estévan, as Austin styled himself, was a clear cut above most public figures of the old American frontier. He was never rough and ready. While his father exploited lead mines and founded a bank in Missouri, young Stephen—a child of privilege—spent three years at a prestigious Connecticut prep school. Then, at a time when most frontier doctors and lawyers never darkened an academic door, he spent two years at Kentucky’s Transylvania University. Later, before his family’s fortune vanished in the panic of 1819, he was elected to the Missouri Territorial Legislature and signed on as director of the Bank of St. Louis. In 1820, just as he was to take up his father’s grant in Texas, he was appointed to a circuit judgeship in Arkansas, yet he sensed that there was greater opportunity beyond the Red and the Sabine.

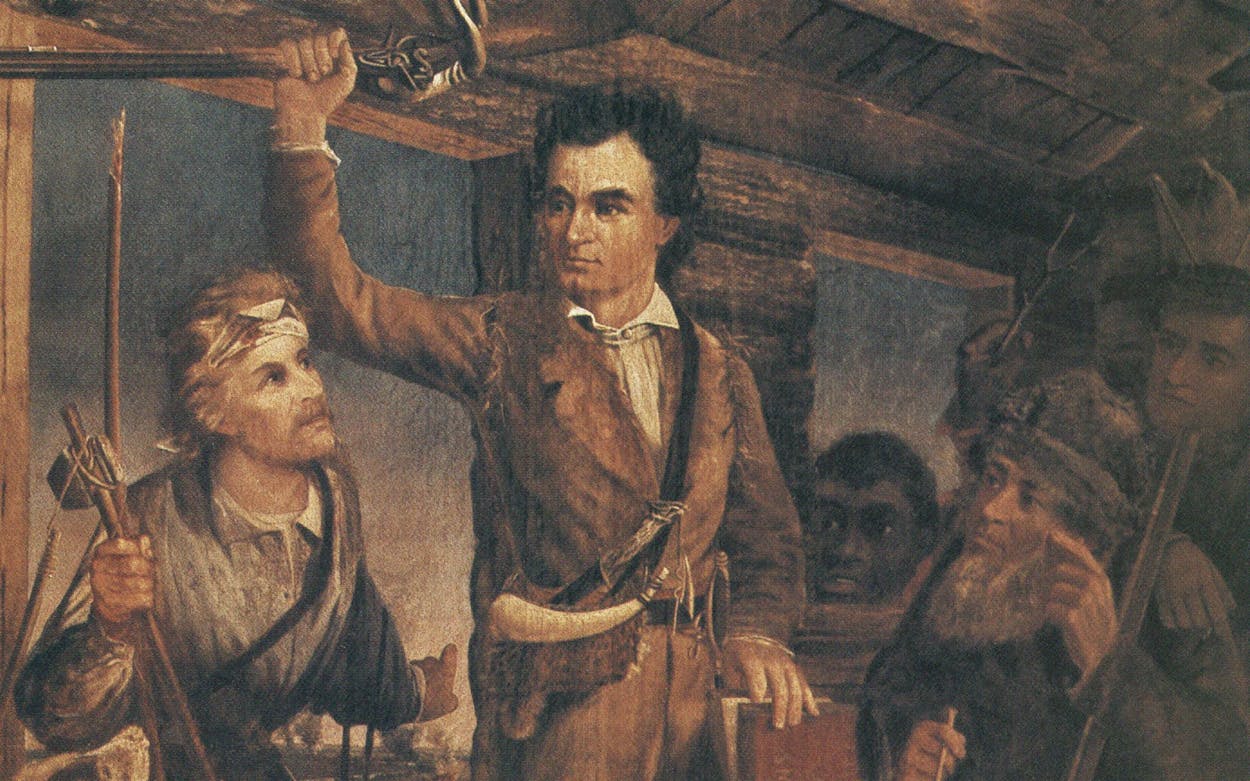

During his life, Austin never married, though no scandal, sexual or financial, ever attached to his name. He was graceful, slender, charming (more so to Hispanics than to Anglos), vastly respected, and eminently civilized—very much the gentleman. In fact, he had little use for “leatherstockings,” the log-cabin settlers of the frontier. The rules he laid out and enforced for his colony stated that “no frontiersman who has no other occupation than that of hunter will be received—no drunkard, nor gambler, nor profane swearer; no idler . . .” (Sam Houston would not have been welcome during much of his career.) When an undesirable did drift in, Austin usually ordered him publicly flogged and sent packing. There were no jails, nor need for any, in his Texas. And he could be tough: He organized the first Texan “ranging companies” (the forerunners of the Texas Rangers) and summarily subdued raiding Karankawa. Yet he despised violence. He much preferred to work out political solutions rather than go to war.

Histories list all this and ring with his praises—and yet Austin is certainly not Texas’ hero. That is because he was not a hero in the frontier sense. He could not sustain his vision of Texas as a prosperous Anglo enclave under benign Mexican rule. He could not stop idlers, debtors, riffraff, hotheads, and lawyers from thronging in. In Santa Anna he faced a Napoleon complex he couldn’t deal with, and he was wise enough to know it.

In 1830 events forced Austin from his position of military leadership. He might have become president of the Republic, but unlike some great personages, he understood his time was done. Shortly before he died in 1837, he served as Houston’s Secretary of State. After his death, he was surely regarded as a great, important man, for the capital city of Texas was named for him.

Austin was an entrepreneur and builder with a frail physique. Houston was a warrior, a general, a president, a senator, and a governor. The former created Anglo Texas; the latter saved it. Even in failure and sometime defeat, Old Sam dominated every stage he trod upon. Austin wanted only for his dream to succeed.

By the way, the “F” in Stephen F. Austin stands for Fuller.

Historian and author T. R. Fehrenbach lives in San Antonio.

- More About:

- Texas History

- TM Classics