It’s not like I didn’t want to work. I had applications out all over town. I was just waiting for the right place to call me back. By this point I’d gone several years without holding down a regular job. I’d lived off a small pile of savings from when I did work, then for a while I’d gone back to school, and most recently I’d been sitting around, wondering what to do now that I was 37 years old and finally out of school and money.

It was Sylvia who came up with the idea of waiting tables. My older sister owns a Mexican food restaurant in Houston that specializes in the regional dishes of South Texas, based greatly on recipes passed down through our family. On the weekend there’s usually a line out the door, and some nights her waiters pocket up to $120 in tips. She offered to let me work at her place, but I was living in San Antonio at the time and wanted to find a job in town.

“Just tell them you have experience working at your sister’s restaurant,” she said.

“But that was only one night,” I said.

“That’s experience.”

“And I was only busing tables.”

“Do you want a job or not?”

A few days later, when the phone still hadn’t rung, I filled out an application at a Pappasito’s Cantina, one of the more than ninety restaurants (including, among others, Pappadeaux and Pappas Bar-B-Q) in the chain started in 1976 by the Greek American Pappas family. The assistant manager I talked to seemed impressed with my experience and hired me on the spot. She handed me a thick binder that contained the extensive Pappasito’s menu, a description of the required uniform (black pants, black shoes, crisp white long-sleeved shirt; the restaurant provided the black bow tie and apron), and the start date of my training schedule.

That night Sylvia called to see how the interview had gone. She was in the car driving the long stretch between her restaurant and the house, a route just west of Houston where the signal is always patchy at best. When the phone rang, I was studying the “Appetizers de Pappasito’s,” trying to memorize that a guest could add spicy ground beef or fajitas to the chile con queso but only fajitas to the nachos.

“They give you tests over the menu?” Sylvia asked.

“Just during that week of training,” I said. “They want to make sure you know everything before you go on the floor.”

“Don’t they have it listed on the menu?”

“Sure, but it’s better if you already have it memorized when you’re talking to the guests.”

“What guests?”

“You know, people who come eat at the restaurant.”

“You mean customers?” she said.

“Here they call them guests.”

Then the line went silent, and I thought we might have been disconnected. A few seconds later she said, “Are you sure you don’t just want to move to Houston?”

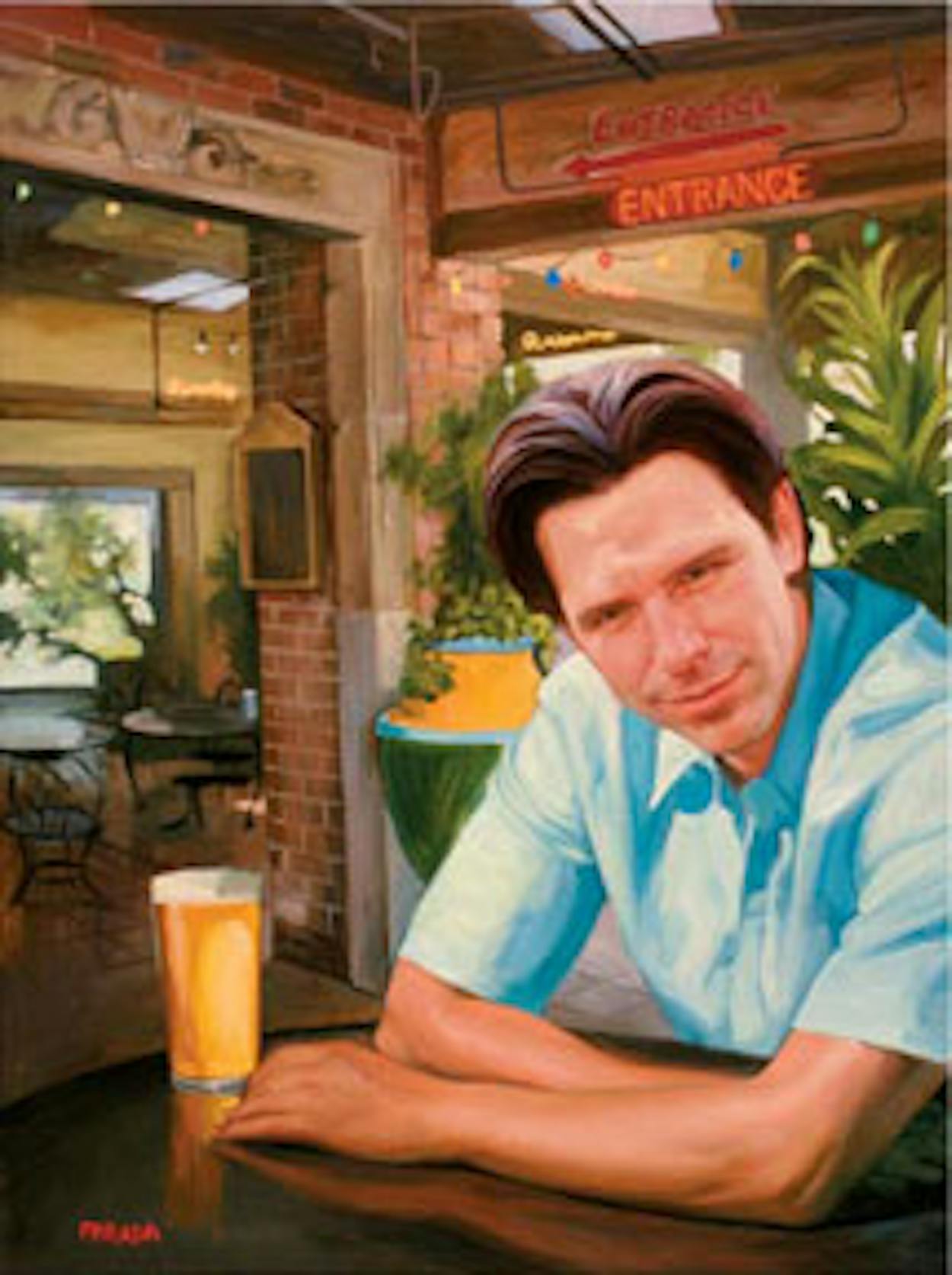

On the first day of training, ten new hires waited in the banquet room of the restaurant. Retro-styled soft drink and “cold cerveza” signs hung from the weathered brick walls. Corrugated metal covered the ceiling, only a few inches above the exposed rafters and the carefully placed speakers bellowing rancheras that spoke of love gone bad and sorrowful caballeros, all made that much more authentic with the occasional chatter of the busboys and the women who busily made tortillas.

After a short pep talk from one of the floor managers, we crowded around in the kitchen to watch a server place an actual order on the touch screen. Ten minutes later, Stacy, the kitchen manager, helped complete the order with two industrial-sized spoonfuls of rice and a cup of frijoles a la charra. The cook adjusted the placement of the sizzling meat on the cast-iron plate, just enough to make room for the dollops of sour cream and guacamole, and then yelled, “Go, go! We’re losing it! We’re losing it!” as you might expect to hear in an emergency room. The “it” was sizzle time. The meat on the cast-iron plate needed to be alive and crackling when it reached the guest’s table in order to create that fresh-off-the-grill appearance. Stacy rushed through the stainless-steel door, holding the tray away from her head to keep from getting sizzle on her blond hair.

That night, I aced my first test with a 99. I missed a perfect score only because, in hurrying to finish, I forgot to add salsa to the list of condiments that get packed into every to-go order. A technicality, really, but I still did better than most people and came out well above the minimum passing score of 90.

The next morning in the break room, the assistant manager introduced me to Bart, one of the top sellers in the restaurant. For the rest of the day I was supposed to follow him as he set up his section, waited on guests, and counted out his receipts at the end of the shift. The night before, I’d seen Bart walking out to his teal-colored Mustang with one of the hostesses. He was a few inches shorter than the girl, but he wore shoes with thick soles and walked with a certain bouncy swagger that made him appear taller than he actually was, though still not as tall as the hostess.

“So you passed the first test?” Bart asked after the manager had left.

“A 99,” I said.

“Not bad,” he said. “But those first tests are nothing. Wait till you see the other ones—those are a real bitch. I studied almost as hard for the LSAT.”

“How’d you do on that?”

“Not as well,” he said, clipping on his bow tie.

We walked out onto the floor so he could show me how a server properly sets up his section. He took one of the shakers off the first table.

“Know what that is?” he asked.

“A saltshaker?” I said.

“That’s what it used to be—now it’s damaged goods.” He held it up close so I could see a tiny dimple along the edge of the metal top, as if someone had tapped it on the table to loosen the salt. He replaced the top with an unblemished one, then picked up the pepper shaker, holding it to the light to make sure he wasn’t missing anything.

At the next table he pointed at the packets of sweeteners, grouped together in their little black caddy. “What’s wrong with this picture?” he asked.

There was a pink Sweet’N Low mixed in among the white packets of pure sugar and another one in with the blue packets of Equal. I plucked each one of them out and placed it in its rightful spot.

“Nice try,” he said, “but all that’s going to get you is rolling silverware.” He was referring to the chore assigned to those who failed to follow restaurant policy. Then he spun the caddy around and set it to a certain angle, identical to every other caddy in the restaurant. “Sweet’N Low always faces the front door, regular sugar always faces the kitchen, Equal always faces the bar. Walk into another Pappasito’s or Pappas restaurant, and if you see the Sweet’N Low pointed the wrong way, you can bet somebody’s staring at a tray full of forks and knives.”

I passed that shift’s written test with a 94. Bart was right about the tests’ getting harder. Now they were asking us to name the six meats that came on the Plato Fiesta, which of those were also found on the Plato Loco, and how each of those Platos was prepared. Still, a 94 was a safe and respectable distance from a 90.

A few days later I followed Bart out onto the floor for his dinner shift, the time when a server can expect to make good money.

“I think we’ll start with the chile con queso,” said an older man at one of the out-of-the-way tables. He was with a young woman sitting a little too close to be his daughter.

“Great start,” Bart said. “I’ll be sure to bring out some warm chips with that. Do you want the queso plain, just by itself, or can I add some of our famous grilled fajitas to that?”

The man looked over at his date, who only smiled back, waiting to see if he ordered the chile con queso by itself, really just a bowl of melted cheese, or one flavored with our famous grilled fajitas. “Yeah, why don’t you add those fajitas?”

“Good choice. Our fajitas are standout,” Bart said. “What about some fresh guacamole, prepared right here at the table?”

“Ooh, I like guacamole,” his date said.

By the time Bart brought around the ticket, he’d added more than $30 to the tab, meaning an extra $5 in addition to what was already a nice tip. If you multiplied that by all the tickets he’d have during a five-hour shift with five tables, you could see why he was one of the restaurant’s top sellers.

I spent most of the shift carrying Bart’s trays and, later in the kitchen, learning how to serve beans. In fact, I served beans during most of training week. You wouldn’t think serving beans—refried or a la charra—would require so much instruction, but the assistant managers believed one couldn’t have too much experience in this department. And really, what did I care? Tomorrow I’d be on the floor earning at least as much as the waiters at my sister’s restaurant—probably more, considering the prices on this menu. All I had to do was pass my last test.

“You forgot to write down the chocolate,” Stacy the kitchen manager said. We were standing outside the break room and had to move aside every time somebody wanted through.

“I’ve never had capirotada with chocolate,” I said.

“Probably because you haven’t eaten capi-rotada here at Pappasito’s.”

“Yeah, but usually it’s just bread pudding and . . . whatever else,” I said, wishing I’d stopped long enough to ask my mother all those times I was stuffing my face.

“Here, the ‘whatever else’ is chocolate.” She actually made the quotation marks with her fingers.

“Well, an 89.3 is practically a 90, right?”

“Sorry,” she said and walked away, her ponytail bouncing side to side from the back of her Pappasito’s cap.

I followed her through the kitchen. “You’re saying you can’t round the score up from an 89.3 to a 90?”

“What I’m saying to you is you need to do the shift over.” She turned around, up close to my face now, and right then I thought I saw something move inside her mouth, a shiny piece of gum or a marble.

“Because I missed a 90 by .7, I have to serve beans again?”

“Because you got the answer wrong.” She reached for a menu lying near the touch screen. “ ‘Capirotada,’ ” she read. “ ‘Warm chocolate bread pudding with cinnamon ice cream.’ ” She read slowly, as if English were a second language for me. “That seems pretty important to know if you expect to be a server. Just imagine if one of our guests was allergic.”

I would’ve paid attention to the rest of what she said, but I was distracted by the silver bead in her mouth. A pierced tongue was the last thing I would’ve expected to see at Pappasito’s, which is probably why I saw it in the kitchen and not out on the floor. All I could think was “Some twenty-five-year-old with a silver bead stuck in her tongue is forcing me to spend another night serving beans because I forgot one ingredient that’s already listed on the menu.”

We might have argued all night, but the night manager walked up and took her side, and then a minute later I quit. I was only a day away from getting on the floor, but already I knew that at some point I’d miss that one less-than-perfect saltshaker or put on my bow tie the wrong way or forget to mention the chocolate.

The phone was ringing when I got home. From the caller ID I knew it was Sylvia. If I answered, I’d have to tell her the whole story. I imagined her telling me it was just a dumb job anyway and that if I wanted, I could still move to Houston and work at her place. At least now you have some experience, she’d say, trying to cheer me up. Then we’d talk about how our mother used to make capirotada and how she was never sure if the recipe came from her grandmother or our father’s mother or some other relative, and Sylvia would laugh because she couldn’t remember if she’d used the same recipe or changed it in some way, and then maybe we’d both laugh, because as much as capirotada might have changed over time, we were pretty sure it was never meant to have chocolate.