This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

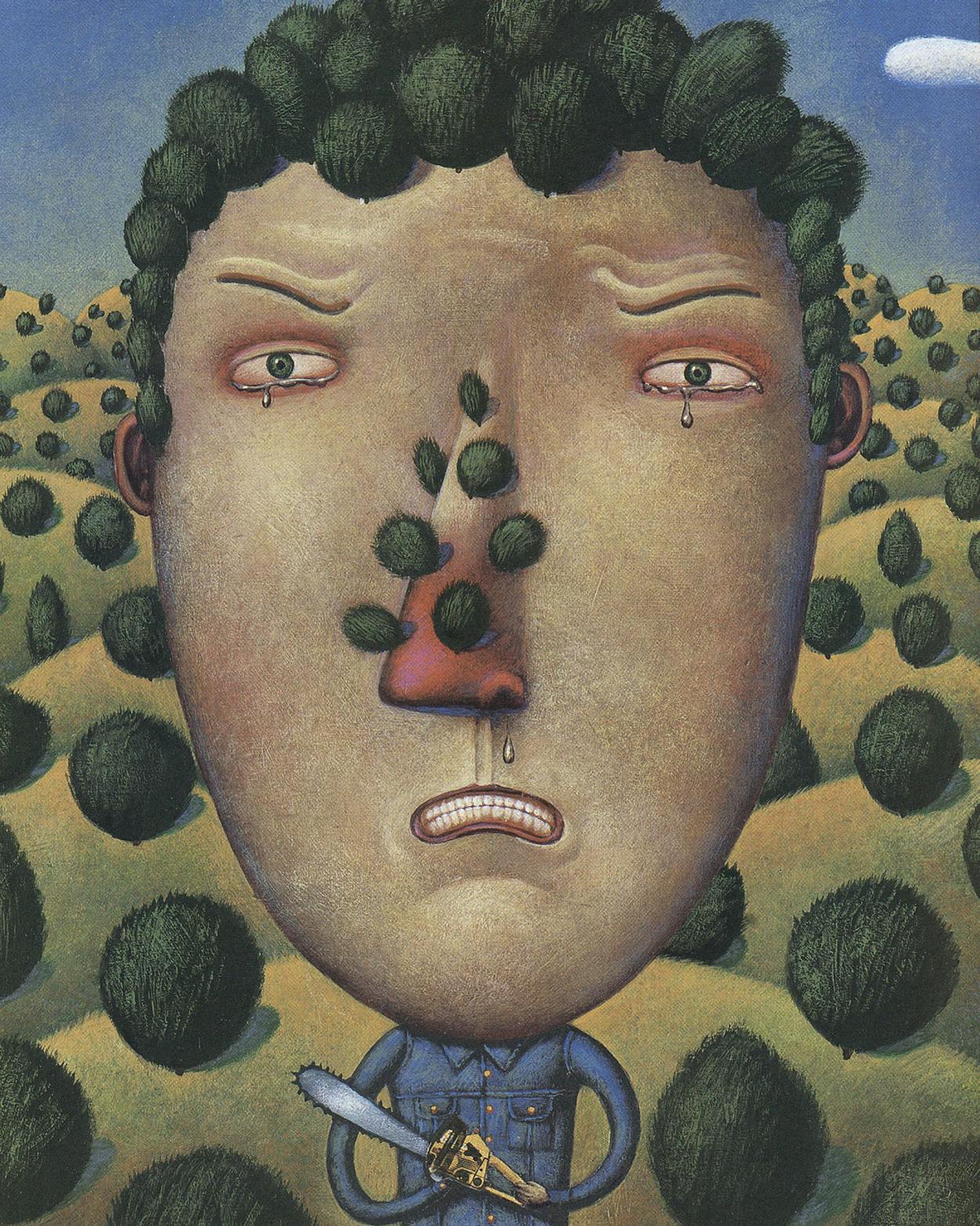

I hate cedar. Especially this time of year, when Central Texas cedars—one of the most prolifically pollinating plants in North America—dramatically release copious airborne pollens in explosive puffs of orange-red smoke whenever cold winds blow from the north. Like gnarly little fishhooks, the pollens invade my nostrils and sinuses. Before long I’m sniffling and vacant, sick and tired. I hate cedar fever.

Since I moved to my nine-acre spread near the Hill Country town of Wimberley four years ago, cedar has become much more than a seasonal pain. In fact, not long after I bought my land, I discovered a different kind of cedar fever, a consuming obsession with the cursed tree. Cedar is an invader of grasslands and a horrendous water hog. It is low in nutritive value, unpalatable to cattle, and altogether unpleasant. It’s well-nigh impossible to get rid of. And it’s everywhere. Almost every one of the decent oaks on my property appeared to be dying a slow death, surrounded by a gaggle of young cedars choking them out, like a group of teenage street punks mugging a senior citizen. Forget mesquite, Johnson grass, sticker burs, and prickly pears. Cedar, as it exists in the Hill Country, deserves the reputation as the vilest plant thriving in Texas.

Well, okay, it does have some positive characteristics. Cedar stays green year-round. Cedar bushes provide natural privacy fencing, blocking out the views of my neighbors’ homes (and vice versa), and they prevent erosion on steep slopes. Old-growth cedar provides cover for all sorts of wildlife and the habitat for a couple of rare, endangered Neotropical migrant songbirds that spend their summers in Central Texas—the golden-cheeked warbler and the black-capped vireo. This last fact, in some people’s minds, is the worst thing of all about cedar, and it has been the cause of a lot of trouble and misinformation in the war on cedar.

I’m a city boy. When I bought my nine acres, I was determined to be a responsible steward, to do the right thing, to disturb the land as little as possible. But cedar challenged my values. I wanted it out of there, by any means necessary. The debate to remove or not to remove became the basis for domestic squabbles between my wife and me, turning into great philosophical entreaties that grew even more spirited after my neighbor, whose cleared grassland resembles a thick, lush savannah, asked me what I was going to do with all those gnarly cedar bushes, especially those that crowded over our fence line.

Cedar, I was learning, is a vegetative Vietnam—it’s hard enough figuring out the identity of the enemy. Is it the government, which in the name of protecting a couple of birds seemed to be telling me what I could and could not do with my land? Is it the warbler and the vireo? Is it overgrazing and lousy land management? Or is it cedar itself?

I tracked down Fred Smeins, a prominent teacher and researcher in the department of rangeland ecology and management at Texas A&M; Mr. Cedar to you and me. The easygoing Smeins calmed me down in short measure and reassured me in a learned, professorial manner.

First of all, he patiently explained to me, not all cedar is cedar. The cedar I was obsessing on is not a true cedar, but actually Ashe juniper, one of seventeen species of the genus Juniperus found mainly in the western United States. It goes by several scientific names—Juniperus ashei, Juniperus sabinoides, or Juniperus mexicana—and is commonly referred to as mountain cedar, post cedar, blueberry cedar, Texas cedar, and Mexican cedar, as well as damn cedar, in addition to just plain cedar. Officially described as a dioecious shrub, it grows in calcareous, shallow rock soils (read: limestone) and flourishes on the Edwards Plateau, the geographic region popularly known as the Hill Country.

Second, Smeins told me, there’s a world of difference between old-growth cedar, which is anywhere from twenty to two hundred years old, and second-growth cedar, which is younger and scrubbier and usually thrives in areas where old-growth cedar has been removed. Though size is one standard of measure—the ancient cedars that were here before we Texans showed up were downright stately—it’s really a matter of heart: The older the tree, the more dense, dark heartwood is in the trunk. Heartwood can be harvested for many things, including fence posts—the basis for the cedar-chopping industry before cheaper metal posts came along in the fifties. Sapwood, the white ring around the heartwood, can make up almost all of a second-growth cedar trunk and is too soft for fence posts or furniture.

Finally, Smeins said, as evil as I might think cedar is, it isn’t really the all-purpose Beelzebub of God’s greenhouse. Yes, he acknowledged, cedar is a terrible curse on the Hill Country, and its spread into grasslands is troubling. “Our research station at Sonora shows if you remove woody plants of any kind, but especially cedar, you’re going to have more water reach the soil,” he said, noting that a fifteen-foot cedar uses 35 gallons of water a day, nearly twice that of a similar-sized oak. But, he added, “Like most things, cedar isn’t all bad, and it isn’t all good. There is no right or wrong. How you look at it depends on your interest. The Edwards Plateau is a microcosm and a convergence of every land-use issue going. If you’re a cattle rancher, you don’t want cedar because it competes with your grass.” A biologist, a birder, or the owner of five thousand acres who doesn’t run cattle might see it in a completely different light.

Smeins also dispelled the belief that cedar is an interloper. “Cedar forests already flourished in canyons and ravines on the eastern edge of the Hill Country and around Utopia and Vanderpool, according to historical accounts of explorers, though it was not common to other parts of the Edwards Plateau.”

He set me straight on a few other things too. When it comes to allergies, female cedars, the ones with the cones and the berries, are minor players. It’s the males that produce all the pollen to fertilize the females. People don’t make gin from the berries of Ashe juniper. They use juniper berries from European plants. And forget the one about cedar’s leaf litter being toxic. “Decomposed litter is actually an excellent growing medium. It’s the lower branches of a cedar bush that block the sunlight and prevent vegetative growth.” As for furniture, Texas cedar is too twisted to compete with the tall, straight cedar from the Pacific Northwest. Nor is it a good idea to use Texas cedar in the fireplace, because of its tendency to throw off sparks and coat fireplaces with a volatile oil. Furthermore, Smeins told me in no uncertain terms, you can’t get rid of it: “Elimination no, management yes.” The most efficient way to clear, or manage, cedar is by fire, though landowners often use bulldozers and chains or axes and chain saws.

Then he looked me straight in the eye. The spread of cedar, he declared, is all man’s fault. Before the settlers arrived, cedar was kept at bay in the Hill Country by periodic wildfires. Fences, the destruction of the once-dominant grasslands by overgrazing cattle, sheep, and goats, and the methodical clearing of old cedar without cutting back new cedar have resulted in cedar’s running rampant, choking out the more aesthetically pleasing oak at every turn. “The live oak is static, a Pleistocene relic in many respects,” he said. “It can’t compete with the reproductive and growth potential of cedar, going from a seedling to waist high in ten years.”

Then Smeins hit me where it hurt. Poor ranching and land-management practices had been bad enough. Now people like me, moving into the hills from the cities, bringing along with us more roads, fences, and subdivisions, were aggravating the situation. “You’re the worst nightmare of all,” Smeins told me bluntly. “It’s difficult enough to do a prescribed burn on ten thousand acres. When that piece of land is subdivided into ten-acre ranchettes like your place, fire is out of the question. And if you don’t burn, you’re going to wind up with more cedar.”

Before I left, he gave me a copy of 1997 Juniper Symposium Proceedings, a collection of academic papers on cedar presented in San Angelo last January. And he showed me a book, Cedar Whacker: Stories of the Texas Hill Country, by C. W. Wimberley, published by Eakin Press in 1988. “Read this,” he suggested. “This’ll give you a good background.”

“Cedar is the bane of the Hill Country,” declared C. W. Wimberley several days later, sitting shirtless at his dining-room table at home in San Marcos, sweating out an unseasonably warm autumn morning. The 84-year-old Wimberley (“C.W. stands for Cedar Whacker”) sifted through yellowed newspaper clippings that reflect his lifelong interest in cedar: growing up around Wimberley (the town was named after his great-grandfather), running a cedar yard in Lone Grove, near Llano, from 1937 until 1959, and writing the book as well as numerous heated letters to the editors of area newspapers.

Wimberley regaled me with stories of seeing, when he was a young man, mottes of virgin cedar along the Colorado River from Austin to San Saba. Most of that prime, valuable timber was cut out long ago, he said, leading to the ruination of cedar choppers and cedar-yard operators like himself. Wimberley spoke eloquently of cedar choppers, the poor, salt-of-the-earth, independent-minded individuals who imbued the Hill Country with much of its folklore. In his book, Wimberley divides them into four categories, the most skilled being cedar cutters, “among the last of the truly independent American craftsmen,” then cedar choppers, cedar whackers (“. . . he could turn good timber into the sorriest looking post, leave a sloven mess where he made a track, give you the shirt off his back while stealing you blind, have you laughing ten minutes after you had hunted him down to break his damned neck, never around when you needed him, and about the time you got around to thanking your Lord for good riddance of the pest, he’d show up again grinning from ear to ear”), and at the bottom rung, the cedar hacker, who “took to the cedars like a blind beaver with the hiccups but with less favorable results.”

Wimberley’s cousin, Dorothy Wimberley Kerbow, a writer and historian herself, told me about the cedar-chopper homes that persisted in the cedar brakes around Austin until the early seventies, ironically in West Lake Hills and Spicewood Springs, now two of Austin’s most affluent suburbs. “Their houses had no doors, no windows, no screens,” Kerbow said. “There were always dogs lying around and trash scattered all over, and there was no yard to speak of. The kids’ faces were smudged with all the charcoal that they burned in piles, and the children came to school with so much cedar wax in their hair you couldn’t comb it out. But sure enough, there was always a television antenna on the roof.”

The tree survived while the old ways died, and Wimberley still hates cedar. It’s greedy and it depletes the soil, which in turn creates erosion that pollutes creeks and rivers. And the second- and third-growth cedar that grew in the place of the old wood is almost worthless. “That sapgrowth has no heartwood,” said Wimberley. “It will rot out in no time.” Then, slapping his hand on the table for emphasis: “Mother Nature is a modest girl! You can’t denude her soil or she’ll cover it with something that cattle can’t eat and man can’t use. Mother Nature is covering her nakedness where man can’t control it.” With a cedar loincloth, no less.

Adding insult to injury, according to Wimberley, is the Sierra Club. He showed me a letter he’d written to the editor of the San Marcos Daily Record and amplified its sentiment. “Their invasion of the Hill Country with the Endangered Species Act without doing their homework has done more harm than anything else. Babbitt, Bobbett—the whole damn thing starts with the Sierra Club.”

Wimberley was referring to the act passed by Congress during the Nixon administration, and the subsequent listings of the black-capped vireo and the golden-cheeked warbler as endangered species in 1988 and 1990, respectively. Portions of 33 counties in the Hill Country have been identified by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service as prime habitat for the birds. In the eyes of Wimberley and many other landowners, the designation made the clearing of cedar illegal, a foolish government edict if there ever was one. The science was suspect and just plain stupid, tying a law to a bird to a plant.

“Look at this,” he bellowed, digging out a pamphlet from the Hays County extension agent, Billy Kniffen, which included a note cautioning against removing cedar from property because of the endangered designation of warblers and vireos. “Political pressures are such [Kniffen’s] got to bow, by God, to the Sierra Club before he opens his mouth. Piss on ’em. We can do without that damn bird, instead of putting up with that damn cedar.”

Well, not really. An unfortunate sideshow of the war on cedar has been the war pitting property owners against environmentalists and the government. High on an oak- and juniper-choked slope on the Post Oak Ridge of eastern Burnet County, Chuck Sexton spent a September morning doing his best to help quiet the hysteria. A wildlife biologist for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the same federal agency that monitors endangered species, Sexton was checking the effects of a cedar-clearing fire that he set last March. Along with a volunteer assistant named Eddie Hertz, Sexton was measuring and then photographing designated zones on the 1,000-acre Nagel tract at the edge of the Post Oak Ridge in the Balcones Canyonlands National Wildlife Refuge. Established in 1992, the 15,000-acre refuge is an existing section of a proposed 76,000-acre federal, state, county, and city conservation plan west of Austin. The idea is to preserve enough habitat for wildlife, particularly the black-capped vireo and the golden-cheeked warbler, in the face of the rapidly growing metropolitan population of Austin that is spilling into the hills. Though the morning was as muggy as a day in mid-July, the birds had flown the cedar brakes for the winter—the warblers to southernmost Mexico, Guatemala, Nicaragua, and Honduras; the vireos to southwestern Mexico.

Sexton, who looked like a Boy Scout with his glasses, brown cap and uniform, and straightforward manner, made it perfectly clear that he doesn’t like cedar recklessly spreading into grasslands any more than the cattle rancher on the other side of the fence. “Overgrazing of native grasses and the absence of fire have created quite an opportunity for cedar and prickly pear, so we’re putting fire back into the landscape,” he said. This burn, however, wasn’t very effective. “You can see our fire fairly sputtered through here, it was so cool and damp on the day we did this,” he said. “It took out some of the junipers, but not many of them. Overall, I think we got about a ten percent kill.”

Sexton didn’t mean that he wants to see nothing but tall grasses waving in the breezes. “The biggest tall tale is that cedar wasn’t here at all,” Sexton said. “There were heavy cedar brakes when man first arrived in these hills, mostly in ravines and canyons where grass fires couldn’t reach. It has always been a heavy woodland component. But there’s a lot more cedar today than there was one hundred years ago, mostly because of us. The Balcones Canyonlands creates the opportunity to protect old-growth cedar in order to protect warblers and vireos and go after cedar like a rancher on the plateaus and watersheds.”

The listing of the vireo and the warbler as endangered was no surprise to Sexton, who, as a wildlife biologist with the City of Austin, had previously determined that more identified endangered species exist in and around Austin than any other metropolitan area in the United States. The implementation did not sit well with many landowners, who interpreted the listing as an excuse for government agents to trespass on their land, looking for warblers or vireos, and then tell the owners how to manage it. The landowners got it wrong, according to Sam Hamilton, who was the state administrator of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in Austin from 1991 to 1995. “The Endangered Species Act [ESA] is pretty explicit about endangered species and their habitat,” Hamilton told me. “If it can be demonstrated what you’re doing is harming the warbler, you can get in hot water. But there were people out there putting out the lie that you can’t cut cedar because of the ESA, which just isn’t true. What is true is that old-growth cedar, the kind that warblers need to survive, is harder and harder to find. In the past we’d issue bird letters with technical advice on how to manage land if old-growth cedar was found and warblers or vireos were nesting there. But the Texas Farm Bureau thought that was inappropriate, so the service no longer issues letters.” Now it falls on the landowner to do the right thing.

While admitting that the bird letter process was tedious, Sexton said that it wasn’t burdensome. “What landowners need to know is there’s a right way and a wrong way to clear their land,” he said. For example, there’s a limit to how much cedar should be in prime habitat, especially for vireos. “If you get too much juniper, it will shade the shin oak, and without shin oak the vireo will leave.”

Sexton has heard plenty of stories like the one that Dorothy Kerbow told me about a rancher who was clearing cedar along his fence line, only to have a curmudgeonly neighbor call the Environmental Protection Agency on him. Sexton takes them with a grain of salt. “We’ve learned a lot from the ranchers and their land-management techniques,” he said. “It’s when the subdivisions pop up and we have forty houses where we’ve had ten to twenty cattle before that create problems. You can’t do prescribed burns in developed areas. The influences of urbanization are far greater than ranching practices.

“Anything we do,” he added later, “we study to see if our techniques are working. We don’t just make a guess as we go along. We do test plots before we do things large-scale.” Whenever a prescribed burn is applied to the entire Nagel tract, I’ll bet a dollar to a dime it won’t be on a cool, damp day.

“If you want to see how cedar can be managed, go see David Bamberger’s ranch over by Johnson City,” Sexton told me. “He went a little overboard in my opinion, but he’s brought back springs and creeks on his land.” In fact, everyone else I’d spoken with had invoked Bamberger’s name at one time or another, though C. W. Wimberley reckoned he was “in with the endangered species boys.”

A clear-eyed, gray-haired gentleman who acts half his 69 years, J. David Bamberger has emerged as the poster child of the cedar war, the guy who did the right thing, the right way. After 28 years of aggressively using bulldozers, chain saws, and lopping shears on his 5,500-acre Selah Ranch, he can witness firsthand the benefits of cedar removal. “When I moved here, I met a representative of the Soil Conservation Service who said he hoped I didn’t plan on ranching because I’d bought the most worthless piece of land in Blanco County,” he said with a chuckle. Bamberger took the remark as a challenge. After leaving Church’s Fried Chicken, where he had been the chairman of the board, the Ohio native searched for a project that would inspire him in the same way that Louis Bromfield, a Pulitzer prize–winning novelist, had. Bromfield wrote four agricultural testaments during the forties and fifties about restoring land, and the results of his handiwork are still visible at Malabar Farm State Park in Ohio, the site of his experimental farm.

“I wanted to do what Bromfield did,” Bamberger said. The land he purchased was perfect. “It was an abandoned ranch, all eroded and gullied, without a drop of water, and wholly indicative of the poor land-stewardship practices of the country, especially in this part of Texas. There were less than fifty species of birds on the land and the biggest deer on the property was field-dressed at fifty-five pounds. You could’ve stuffed it in an Albertson’s sack.”

Bamberger, rich and eager, got busy and hired a staff that is still with him. Thirty-eight chain saws and 13,000 bulldozer-hours later, his ranch is a Hill Country dream. Streams run year-round. Grasses are tall and lush. Diversity rules. “The count of bird species is up to one hundred and forty-eight. Last year the smallest deer field-dressed at one hundred and five pounds. The evidence is there in every spot.” Bamberger clearly revels in what he has wrought and relishes his emerging role as an evangelist of smart land management. He leads seminars, conducts tours of his land, and speaks out on land-use issues, frequently advocating ideas and concepts that fly in the face of conventional wisdom about property rights. “I’m a smartass and I’m brash,” he admitted. “But I’m right. I’ve improved my quality of life, and I’ve improved my bank account.”

He’s proud of the fact that he’s a private landowner protective of his property rights who nevertheless testified in front of Congress in support of the ESA. “I told them if you don’t reauthorize the act, you’re sending the message that conservation and environment issues are no longer important,” he told me. He has spoken to the Trans-Pecos Heritage Association in far west Texas, arguably the most vehement property-rights advocate group in the state. In his not-so-humble opinion, landowners who fight the ESA or take the attitude that “this is my land, keep off” are just plain misguided, not only because they’re discouraging wildlife diversity but also because they’re losing out on a chance to make some money off their land. “If you are just a greedy robber baron and don’t really care about Mother Nature, you still should encourage endangered species, because ecotourists will pay good money to see them,” Bamberger said. He cited the example of Victor Emanuel Nature Tours, a $4 million business based in Austin that conducts wildlife tours around the world. The only tours Emanuel schedules in Central Texas are those to see the golden-cheeked warbler and the black-capped vireo. “One ranch near Concan made $14,000 last year by hosting a few busloads of tourists,” Bamberger said. “All you do is open the front gate and look at people ranching like you used to look at cattle ranching. The big difference is these folks don’t require feed and, unlike hunters, they don’t shoot.”

Bamberger wants more visitors like that, so he’s working to attract more vireos and warblers by trimming stands of old cedars (making sure there’s plenty of cedar bark for nesting material), fencing off areas to encourage vegetation that provides birdseed, and removing new-growth cedar saplings that compete with the older trees. The process is ongoing. “Go into your cedar-clearing proposition with that in mind,” he said. “Never initiate an action that you don’t intend to sustain. After you cut cedar, don’t burn it; stack the dead wood in windrows on a slope to catch soil and runoff. Keep dead branches around the trunk trimmed back. Cut any new growth that you see.” Bamberger figures he’s kept about three hundred acres of older cedar as wildlife habitat, hoping to attract more warblers and vireos. He knows that neither species can survive in a forest that is exclusively cedar: “They need oaks and grasses and water nearby. The warbler wants cedar for one reason: to build its nests with cedar bark. The warbler flies into Spanish oak, finds a certain web made by a caterpillar, and holds its nest of cedar bark together with the webbing.”

One of the first stops he makes during his land-management seminars is a clearing by a cedar thicket where 37 lopping shears are lined up. “This is a Tom Sawyer deal,” he said, grinning. “I show them all the kinds they can buy in the store and let them try them out for ten minutes or so, trimming dead branches.” A few minutes later, by the banks of a small lake that he nurtured by clearing away rocks and vegetation from the mouth of a dormant spring, he showed me two metal trays, one containing grasses, the other containing a few cedar seedlings, with showerheads above each tray and a faucet and a jar at the bottom. “This is my rainfall simulator,” he said. The showerheads rain equally over the trays, and the runoff collects in the jars. The tray with grasses absorbs the water and takes about ten minutes to fill up with clear water that’s been filtered by the soil. The water runs right through the tray with cedar and fills up in about three minutes with muddy, silty water. “Now which one do you want?” he asked.

He led me down an interpretative walking trail lined with specimens of pin oak, Chinese pistachio, Texas madrone, bald cypress, cedar elm, bigtooth maple, goldenball lead-tree, and Blanco crab-apple. “I’ve reintroduced over three thousand trees that were browsed out by overgrazing,” he explained. He showed me his eleven concrete spring boxes, or cisterns, that supply all his water needs on the ranch, without pumps, water wells, pressure tanks, or filtration devices. He pointed out the herd of scimitar-horned oryx, “the only genetically pure herd on earth.” He took me inside the one-of-a-kind artificial bat cave under construction (Reporter: “Winging It,” September 1997).

Bamberger was quick to acknowledge that not everyone can buy his own 5,500-acre spread and afford a bulldozer and a crew of hard-working hired hands to clear out the cedar. “But if you have nine acres, you can afford a pair of lopping shears and a wheelbarrow and still make a difference.”

A sense of urgency permeated everything Bamberger said and did over my two-hour nickel tour of Selah Ranch. Back at his hilltop home, he explained why. “We’re the endangered species,” he said. “Kids growing up in a world of McDonald’s and graffiti are going to be making the decisions in the future. I want them to see what their world can be like. That’s why I’m telling the private landowners they’re holding on to a myth. It’s not like it was one hundred years ago. We don’t own this land. We’re only stewards.”

The more I looked, the more I learned. Cedar, it turns out, isn’t totally worthless. The cedar choppers and cedar yards may be long gone, but their legacy hangs on in the form of four processing companies that distill thousands of pounds of Texas cedarwood oil (also known as cedar oil and juniper oil), a key ingredient in all sorts of fragrances, including, according to cedar lore, that cleaner-than-clean aroma in Tide detergent and that peaty fresh smell in Irish Spring deodorant soap. Three processors—Paks Corporation, Chem-pac, and Cedar Fiber—are located around Junction, the geographic heart of the Hill Country cedar forest, and have been major job providers since the first mill went into operation in 1929. Texarome, a smaller fifteen-year-old operation with its own refinery that allows customers to buy specific grades of oil and custom blends, sits on the banks of the Frio River outside Leakey. The processors use only old-growth cedar that has been dead for at least twenty years. Next door to Paks is the next-generation plant belonging to the AERT Corporation (Advanced Environmental Recycling Technology), which uses spent cedar left over from Paks’s juniper oil process and recycled plastic to create cedar fiber, a durable all-weather particle board. “Cedar has put a lot of people through school and lot of beans on the table,” said Don Baugh, the vice president and general manager of Paks.

Getting oil from deadwood cedar is a simple process, according to Baugh. “All we use is wood and water,” he said. “First we hog [grind] it, make it into big chips, then hammermill it into smaller chips, then steam the oil out of the wood and let it condense and separate, draining off the oil that floats on top of the water. Cedarwood oil is literally essential oil. We grind it up and what’s left is the soul of the tree.” The oil is placed in storage tanks and shipped in five-thousand-gallon tanks to Holland and England, where it is refined into cedrone, cedrenyl acetate, and other distillates. The operation is set up to run 24 hours, seven days a week, “when the wood is available.”

Unlike its competitors, Paks runs its own harvesting operation, with machines that pick up the wood and pile it high, then drop it in a trailer that hogs the wood. The process is so efficient that nine people using a grappler, a prehauler, a chipper, and a trailer can cover fifty acres in a day. If only there was that much wood to gather. Over the years the stockpiles have gotten so meager that the company has had to expand its range, seeking wood as far as 75 miles away. The other processing companies depend exclusively on cedar haulers, the modern descendants of cedar choppers, to do their legwork: finding deadwood on ranches, making a deal with the landowner to remove it (usually something like, “I’ll clear this stuff off your land if you want me to, for free”), piling it onto their trucks, and delivering it, earning $38 a ton.

“I’ve got a lot of things to figure,” said Baugh, who keeps lists of large landowners and recent land transactions in the Hill Country and studies topographical maps and aerial photography in search of a pile. Once he’s found it, other factors kick in: “How far is it to fetch the wood? Will I have to build roads to get it? Is the heart of the wood dense enough? We can’t set up on six hundred acres or smaller tracts of land.”

By sight alone, Baugh can tell the difference between cedar from different counties. “See how yellow that wood is? That’s from Sutton County,” he said. “This wood, from Kimble County, is a lot denser. Unfortunately, I can’t be picky. We’re down to getting smaller branches that were left behind when the wood was first harvested years ago. We’re kinda like the old buffalo hunters. We were running out of wood back in the sixties. We see a little less every year, but there’s still a lot out there. I’m tickled to death if I can find cedar with ax marks on it. That means it’s really old and was cut a long time ago. Chain saws didn’t come along until the late fifties. Mind you, we’re looking for heartwood, first-growth cedar that has a round top. Second-growth cedar sure can’t be harvested for timber and is of little use to us. Second-growth cedar doesn’t make a tree, it makes a water-hungry shrub. It has a heart like a banker’s.”

The chip waste is used for horse and poultry bedding, mulch, as filler for crevices in holes drilled in the oil fields, fuel for the mill’s boilers, and for wood composite at AERT, one of the largest employers in Kimble County. The Texarome plant in Leakey even uses small amounts of fresh cedar leaf from green second-growth and third-growth cedar in response to a small but growing demand from aromatherapists, who desire a fresher, stronger scent.

“We’ll continue to do what we do until we can’t do it,” Don Baugh said. “Our challenge now is to make more oil from less wood for less money.”

“I have one fear,” he confided to me before saying good-bye. “And that’s when I die and go to heaven, God would be a cedar tree.”

I’m no longer hysterical. I understand cedar much better than I did before. I know that it’s not the all-purpose bogeyweed—a tool for big-government intervention or the cause of the ruination of the cattle industry. I can now see in an elegant old cedar the same grandeur and beauty I see in an old oak. I’m thankful for the presence of cedars on steep, rocky slopes, recognizing the role they play in stabilizing the soil and providing windbreaks. I’m happy that a few people can still make a living off cedar. I’m cheering on the concept of aromatherapy. Maybe some enterprising rancher or modern-day cedar chopper will find more uses for new-growth cedar.

Those people can have mine. Not all of it. Like I said, I’ve learned to respect and even appreciate my foe. And I’m not foolish enough to try to clear the whole lot at once. This battle will be a protracted one, fought literally one step at a time. The teeth on my chain saw have been sharpened. I’ve conducted my own seminars with my sons, showing them how to use lopping shears to earn a little money. I still dream of the way it used to be, when grasses grew as high as a horse’s belly.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Wimberley