The old yearning toward physical self-sufficiency for families and clans runs strong in uncertain times. It is stoutest in the country if only because more self-sufficiency is feasible on dirt than on pavement, and nearly all of us rustics, whether we have “returned to the land” or never left there in the first place, have a medium-to-large shot of it flowing in our veins. Society being complex and many-tentacled, self-sufficiency these days tends to be fragmentary at best, but that doesn’t lessen an addict’s satisfaction in short-circuiting the Great Machine, cheating the System, rolling his own, and coming up with something he needs and can use, general at small cost. No home regardless of its structural quirks will ever be more his than the one his hands have erected or restored to beauty and function; no meal will ever fill him more pleasantly full than that dinner in lavish June when every piece of food on the table, save perhaps a little olive oil and salt and such, comes off his own place.

As for drink on that same table, someone has written also that no wine will ever taste bad that you have made yourself, a statement with a nice ring to it that crops up in books and articles on home winemaking. Unfortunately it is a lot of Pollyanna nonsense. Unless the average beginning winemaker has extraordinary luck in the matter of his raw materials as well as in the details of his manipulations of them, and unless he has a very shallow awareness of just how good wine can be, his is going to turn out a certain amount of what even he can recognize as slop. He is going to turn out some potable wine too, whether sooner or later, and when he does he is going to give it the full benefit of a doubt because it is his own, as I do when I tell myself (and sometimes others, to my shame) that a particularly early batch of acid red, made by guess and by God from garden grapes of indifferent quality, is better than some wine I have had in Europe—without adding that in far nooks of Pyrenees and elsewhere, long ago in roaming days, I have been served some really awful, tooth-roughening stuff.

As for drink on that same table, someone has written also that no wine will ever taste bad that you have made yourself, a statement with a nice ring to it that crops up in books and articles on home winemaking. Unfortunately it is a lot of Pollyanna nonsense. Unless the average beginning winemaker has extraordinary luck in the matter of his raw materials as well as in the details of his manipulations of them, and unless he has a very shallow awareness of just how good wine can be, his is going to turn out a certain amount of what even he can recognize as slop. He is going to turn out some potable wine too, whether sooner or later, and when he does he is going to give it the full benefit of a doubt because it is his own, as I do when I tell myself (and sometimes others, to my shame) that a particularly early batch of acid red, made by guess and by God from garden grapes of indifferent quality, is better than some wine I have had in Europe—without adding that in far nooks of Pyrenees and elsewhere, long ago in roaming days, I have been served some really awful, tooth-roughening stuff.

But, like doctors, we dabblers with wine have the privilege of burying our worst mistakes, as the live oaks around my house can bear witness, their roots having absorbed several libations of fluid judged unfit for human consumption after fermentation and aging. And eventually we grow warier, wiser, and a little better at our craft—or at least I assume from watching others that “we” do, my own experience having been limited and sporadic to date and my growth having reached only the wary, half-wise stage. The idea, of course, is to produce something that people can not only drink but like, and thus far I have turned out only a modest quantity that could be offered to visitors with a fair chance of achieving this. Most of it has been mead, which is honey wine, the stuff our distant Nordic forebears guzzled from bull’s horns and human skulls in warriors’ halls in winter, while banging on the table for more roast wild pig and telling philosophical tales of murder and pillage and rape along the Irish coast.

No guest of ours has been rendered violent from quaffing this mild beverage, made dry rather than sweet and without any heavy spicing. It is a good table drink, especially with light food. True, it isn’t really wine, but then neither are many of other concoctions that the fermentation fever leads us beginners into brewing out of peaches, blackberries, plums, potatoes, and other organic matter. Sugar plus enzymes yields alcohol plus carbon dioxide, goes the oft-cited equation, crudely put, and anything left over is flavor, which in skilled hands can be manipulated with sometimes surprising success, as when what started out as the juice of parsnips or rhubarb stalks, for instance, may end up tasting like a pretty good dry sherry.

Usually, though, what comes out is less epicurean, not that this matters hugely to the average home practitioner, in whom pride of creation most often outweighs such picayune matters as flavor, unless the flavor is truly vile. In its purest form, I suppose, this attitude was to be found on the Pacific islands during World War II among uniformed makers of jungle juice, which they fabricated out of canned fruit cocktail or dried prunes or whatever presented itself, and, waiving other criteria, evaluated purely on jolt. Elsewhere in later years, undoubtedly out of cultural prejudice, I have thought to see the same principle at work in such regional products as retsina and pulque. The applicable equation here seems to be person plus alcohol in whatever form but in sufficient quantity yields kick plus eventual headache, and so it has ever been. Crudely put.

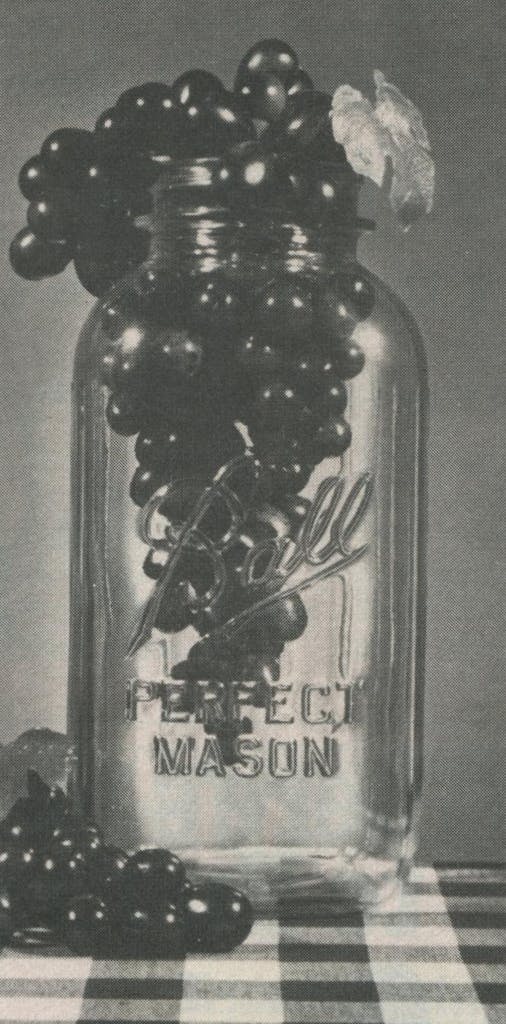

And yet, infected with cosmopolitanism of our time and of whatever reading and travels lie behind us, we amateur fermenters do aspire to more civilized production—i.e., to real wine usually imbibed at least as much for the way it tastes as for what it does to the taster. Real wine is of course the transmuted juice of the grape, that magical, simple liquid wich the Greeks said was brought to them by a god, in whose honor they held great annual orgies, and which the otherwise rational French compare to sunshine itself. Imitating it through the use of other materials than grapes is very hard—and rather silly too, since making it doesn’t amount to much or doesn’t seem to, as anyone knows well who has watched a French or Spanish or Italian farmer laying in his year’s supply. In it simplest red-wine form, the process consists of gathering ripe, sweet grapes, mashing them with bare feet or otherwise, letting the whole mess bubble for some days in a tub before pressing the juice from the hulls and seeds and fermenting it still further, and finally sealing it into barrels or big pots or whole tarred animal skins where it will age before being bottled, if indeed said farmer bottles it at all. The grapes’ sugar has obeyed the equation and turned to alcohol, and various other nice things have happened, and what results is dry table wine, most often good.

But that simple transmutation is itself a miracle, and nobody knows this better than the peasant farmer himself, who may be phlegmatic regarding his wife, fatherland, house, crops, and practically everything else, but is uncontainably proud of the wine he has made and will be your brother forever if you drink some and show you like it—a phenomenon I understand better after having made a little myself. Once a very long time ago I went with a friend to the remote village of his birth on the slopes of the Gredos mountains, west of Madrid. It was August, the time of harvest festivals, and the village was a pleasant one where everybody seemed to have a little usable land and a few animals and enough of life’s necessities to get by well in good years. They put on a fine fiesta too, with elaborate fireworks on a ruined castle’s wall at midnight, a week-long, never-ceasing dance to the music of clay flutes under great poplars by a clear swift river, fighting bulls turned loose in the main square to gore some of the town’s young bravos and in turn to be hacked and stabbed to death inchmeal with scythes and old swords and other hardware by those vengeful bravos who remained, and all sorts of further glories. But its main features as far as I could tell was the sampling of other folks’ wine.

This wine was made and kept on the mountainside above the town in numerous small caves, some of them natural and other dug out of the dirt and rock centuries before, their entries walled up with stones and stout doors set therein. Each belonged to an individual family. In the cool dusk of their depths rows of big tinajas—pots shaped like the amphorae of the ancient world but seven or eight feet tall and holding maybe seventy-five gallons of last year’s wine and sometimes wine from the years before—stood in wooden racks against the walls. We clambered from cave to cave, exchanging pleasantries with their owners in the measured formal Castilian and accepting wine drawn from spigots into rough earthenware cups without handles, made especially for the fiesta and laid in by hundreds beforehand. Occasionally there were edibles too—bitter olives or little morsels of grilled mutton or fish or sun-cured ham or the like.

Drinking with elbow high, you paid rolling compliments to each wine’s particular merits, though in truth with the same grapes and methods prevailing throughout the village there was no great difference from cave to cave in what came out of the spigots—honest stout red wine with a bit of an edge to it behind the chill of the mountain earth. In return for the compliments you got more wine and great rough Spanish embraces, and when you were taking your leave you raised your clay bowl ritually and dashed it against the floor. By the end of the week there was a considerable midden of busted crockery to wade through on our rounds, and the town had quite a few cases of what the Bible calls redness of eye and wounds without cause, and I had made a lot of new friends whose names I no longer recall. I remember the name of the village, though, and if ever I get back there I hope it’s in August and those pagan pipes are tootling ceaselessly by the river and in the hillside caves wine bowls are being smashed, as most likely they have been smashed since Roman times or before.

Whatever may be your own memories, if any, of Old World peasant friends and their wine, you come up against a couple of hitches when you seek to emulate them by making your own here in Texas or roundabout. The first hitch isn’t serious—the fact that behind those peasant farmers’ every action lies a couple thousand years of family and cultural experience, whereas behind yours lies only a fervent and ignorant desire to be your own Dionysus. You can get around this trouble handily by reading books and utilizing the soft technology they lay before you, modernity’s substitute for traditional “feel.” You learn to adjust the grapes’ sugar content and acidity and to guard your ripening hooch against spoilage organisms by the use of such things as fermentation locks and Campden tablets. You achieve the clarification of cloudy wine, and you become very edgy about ambient temperatures—a problem in these latitudes, where grapes come ripe in summer when the weather is too hot for prime fermenting conditions. (The contemporary answer is air conditioning, though that is hard technology and sits but poorly on the conscience of real self-sufficiency types, who would prefer a cave.) And thus in time you stand a chance of reaching a point where you can more or less consistently make the most, or anyhow not the least, of your raw materials’ potential.

But those raw materials themselves—the grapes—are the really big sticking point for most of us American would-be peasants, or have been till just lately. What our counterparts across the water have to work with is one variety or another of the Old World wine grape, Vitis vinifera. In this country, because of harsh winters and various diseases and parasites, that supreme and proven species grows well only in California and a few restricted patches of territory elsewhere, as wine enthusiasts from the time of Thomas Jefferson and beforehand have had to learn the hard way. So the average American winemaker, if bored with elaborating grape juice, has had to depend on the wild grapes that grow in profusion all over the continent or tame varieties derived from them, the so-called American bunch grapes like Concord and Delaware. They make good juice and jelly, but their wine on the whole is disappointing by accepted standards. It can be and often is sweetened into kosher-type of “pop” wine, which isn’t much different from jungle juice of whatever derivation, though when disseminated commercially along with California port and Tokay it does serve the social function of keeping skid row soddenly content except on mornings-after, when sodden discontent sets in.

Here in Texas, with its physical breadth and its spectrum of climates and soils, more species of wild grapes occur than anywhere else on the continent, and a similar diversity of tame types can be grown. In parts of the Trans-Pecos region even European vinifera vines will thrive, and they have been tended around El Paso since Spanish days, though I’m told the old winery there is defunct. At the opposite end, in forested damp East Texas, the Southern muscadine reigns, another sweet-wine grape. And in between where most of us live, a little bit of everything else can be found, subject to the vagaries of soils and diseases and rots and fungi. From these grapes, wine has been made since white men first showed up—good, bad, or indifferent wine, though mainly, alas, of the latter two types.

Of them all, I suppose the one most tangled with Texas tradition is the wild mustang grape, whose thick vines with umbrella-drooping leaves deck trees and fences throughout the central regions of the state, from the Red River to the Rio Grande. To arriving Germans in the Hill Country 130 years ago those vines with their big dark grapes looked like a gift from Herr Gott, for among immigrants to Texas these were the champion self-sufficiency fiends of all time, fresh from European traditions and wanting their own wine more ardently than any of us moderns can. Their heaven-directed gratitude, I am certain, crumbled badly when the time came to taste the first vintage of mustang red, whose characteristic acidity, unless masked by a good bit of sugar or otherwise ameliorated, is enough to tie an unwary bibber’s tongue into fancy Turk’s-head knots. Chronicler “Texas John” Duval, a contemporary of these Teutons, claimed to have once brewed up a large commercial batch of this wine that blistered and twisted the rubber boots with which he had furnished his grape tramplers and in the end couldn’t be sold because “all who sampled it said it was too sour for vinegar and too fiery for aquafortis.”

Nevertheless, the Hill Country Germans were and are a persistent folk, and eventually they learned to cope with the mustang grape’s worst qualities and ended by shaping a sort of tradition around its wine. Even after tame grapes—not very good ones, true—adaptable to the region’s peculiarities were found and brought in, plenty of people there kept on making the mustang red. Most of us who have frequented those hills have tried it, and many of us have made some on our own. The best is more or less sweet, and of most it can be said, as of the illicit white whiskey that used to be distilled in these other more northerly limestone hills where I now live, that it’s not bad if you don’t have anything else to drink.

But now the good tame grapes are here, or seem to be. Here and there and elsewhere. Nearly everyone with any interest in the subject has heard about them by now—the “new” French-American hybrid grapes that have been spreading by fits and starts in this country since their commercial introduction, in the late 1940s, by Philip Wagner of Baltimore. Their potential has been a basic motivating force behind the establishment of scores on scores of new wine-oriented vineyards, amateur or commercial, in many hither-to improbable place like Ohio and Arkansas and Wisconsin and Texas. Another strong factor, of course, has been the spread of wine drinking and the rise in demand and prices, as more and more American have found out what they have been missing.

These hybrid grapes, in an almost bewildering number of varieties adapted to different conditions and purposes, have been under development in France since the last century, one outgrowth of the panic that hit the European wine industry after accidentally introduced American parasites and diseases nearly wiped it out. They are in steady use over there for making not great but good, acceptable wine. At their best—they combine the climatic hardihood and disease resistance of American species with much of the winemaking quality of the old Dionysian vinifera, and they’re doing well just about all over the U.S. except far north where the growing season won’t give them the time to ripen, and in sections of the South where endemic ailments like Pierce’s disease do not let anything but muscadines prosper.

Much of the publicity given them so far in Texas has had a hoop-de-doo commercial tone: plant grapes and get rich. It has centered mainly on the Panhandle High Plains around Lubbock, where some painstaking experimentation is underway, but other nodes of hopeful activity exist or are shaping up in the Hill Country, along the Rio Grande, and in North Central Texas, with a renewed interest in vinifera culture beyond the Pecos. Optimism is cold-watered from time-to-time by sober analysts who point out that it took Europe centuries to evolve its truly great grapes adapted to restricted, often tiny regions and to develop fine wines from them, while California is still learning after nearly three hundred years of winemaking. So even with a scientific approach it could be a good span of years before we have any idea of what may eventually be the potential of wine grown and fermented in Texas—or in Arkansas or Virginia or Missouri. And it may be a few more years than that before people start getting rich out of the process, if indeed many ever do.

But somehow I doubt that when the dust all settles, getting rich will prove to have been the main point. In a muted and small-scale but probably significant way, what appears to be on the verge of happening here has some kinship with the introduction of Vinis vinifera into Europe from the Middle East away back in prehistory, whether it was brought by a god or whoever. Large parts of North America including Texas are being quietly furnished with a basis for making most honest native wine of adequate quality, and some is already being made. Honest wine taken in moderation is like bread and cheese and meat, and has been prized forever as a staple blessing in all lands where wine grapes could be grown. It seems dubious that for all our present shrill urbanism and our technological insulation from earthy things, we are different enough from other men to turn down something, when offered, that has meant as much as good daily wine to humanity. I suspect that in time (and what after all is time to the vines, once here?) a new and perhaps gentling element will creep into American life, born of the activities of thousands of vineyardists and winemakers—some professional but most of amateur or part-time, some hoping to cash in big but most doing it simply because they want to—who now are and in the future will be feeling out the possibilities of these grapes and their offshoots in different regions and climates.

Yes, I’ve got mine started—something over a hundred vines of seven varieties, planted last spring, of which six varieties are doing fine and the other has gone chlorotically yellow and stayed that way despite applications of iron and potassium, but I expected more trouble than that in this limestone soil of mine. If in the long run just two sorts do well here—say, one good red and a white—I will have what I was after and will toast my friends in my own solid wine when they come out to visit. There might even be a cave as well wherein we can do the toasting, for I have been studying out the possibility of gouging a great slot in the hillside behind our house with a bulldozer and building a long cellar in it to be covered over with thick cool earth… Maybe in a few years we can smash some clay bowls there.