Ten years ago this August, Sean Morris and Ryan Ringnald loaded their things into boxes and moved into their dorm rooms at Penland Hall, just two of the 3,168 freshman who would matriculate at Baylor University that fall. Their lives have since taken a more unusual trajectory. The duo, along with a third young man, now lead a small, zealous congregation in east Texas that some consider to be a cult. Many of the church’s ninety members, who arrived in Wells in 2012, are estranged from their families, and they alarmed locals in May of that year when they allowed a newborn baby to die, choosing to pray over the struggling infant instead of calling a doctor.

Friends and college classmates have been following the developments with the Church of Wells with, as one said, “fascination and sorrow.” But a number of peers said that they are not entirely surprised by the men’s fundamentalism, having witnessed the beginning stages of their transformation at Baylor.

Morris, lanky with brown hair, majored in religion but didn’t participate in any traditional extracurricular activities, according to directory information supplied by the registrar’s office. Instead, he filled his time between classes preaching from atop a milk crate in front of Tidwell Bible Building and buttonholing people to question them about their faith, former friends and classmates recounted. Robert Reed, who transferred to Baylor in Fall 2006, recalled Morris approaching him during his first year on campus and asking him how much he hated himself when he accepted Jesus. “It was clear he was not ready to accept anyone as an authentic Christian unless they did it his way,” Reed said. And that remains the confrontational way members of his church approach people. “He’d always pick out these very specific verses about fire and brimstone. He completely missed everything about love or gentleness,” said a friend who graduated from Lutheran South Academy with Morris in 2004 and went on to room with him during their sophomore year at Baylor.

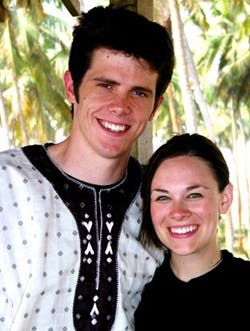

Kasia Maartens, who dated Morris for almost two years between their sophomore to senior years, recently recalled watching his faith shift more and more towards fundamentalism over the course of their relationship. Maartens and Morris met in 2004, when they were both freshman at Baylor. “When I met him I couldn’t stand him,” she said in her tidy apartment near the Houston Galleria. He had recently found Jesus and she said she found his constant evangelism off-putting. But the following summer, which Maartens spent at her parent’s house in Pearland, she became good friends with Morris’s cousin, Cory McLaughlin, a talented artist who had recently graduated from Southwestern University. As her own interest in the bible grew, the three spent many hours in nearby Clear Lake discussing religion and studying scripture. Maartens even let McLaughlin photograph her laying in the street in downtown Houston, a photo that served as the basis for a painting he later did of a dead girl with a hole clawed out of her back, intending to represent “apathy in the church.” (The words “She was not killed by an individual but by the silence of many” are painted across the top of the canvas.) By the end of the summer, Maartens’s parents were unhappy with how these new friendships were influencing her, feeling she had begun disrespecting her family in the name of following God.

Kasia Maartens, who dated Morris for almost two years between their sophomore to senior years, recently recalled watching his faith shift more and more towards fundamentalism over the course of their relationship. Maartens and Morris met in 2004, when they were both freshman at Baylor. “When I met him I couldn’t stand him,” she said in her tidy apartment near the Houston Galleria. He had recently found Jesus and she said she found his constant evangelism off-putting. But the following summer, which Maartens spent at her parent’s house in Pearland, she became good friends with Morris’s cousin, Cory McLaughlin, a talented artist who had recently graduated from Southwestern University. As her own interest in the bible grew, the three spent many hours in nearby Clear Lake discussing religion and studying scripture. Maartens even let McLaughlin photograph her laying in the street in downtown Houston, a photo that served as the basis for a painting he later did of a dead girl with a hole clawed out of her back, intending to represent “apathy in the church.” (The words “She was not killed by an individual but by the silence of many” are painted across the top of the canvas.) By the end of the summer, Maartens’s parents were unhappy with how these new friendships were influencing her, feeling she had begun disrespecting her family in the name of following God.

Over the next six months, Maartens barely spoke with her parents, and began to rely more and more on her friendship with Morris for support. She was a regular guest at communal dinners and bible study sessions at his apartment, and they both attended Antioch, a nondenominational church in Waco whose members eagerly recruit Baylor students. “Everyone there was having the Lord showing them things and visions,” she explained. “And Sean had the Lord telling him that we’re supposed to get married someday.” So, in April of their sophomore year, Maartens agreed to start dating him, but it was never a physical relationship, nor a particularly romantic one. “There’s a psychological theory, proximity theory, where if you’re around someone so much you start liking them,” Maartens said, explaining her college decision. Morris and Ringnald refused to comment for this piece.

And as the relationship progressed, Morris grew more and more controlling, according to Maartens: he complained that her clothes—even sweatpants—were too immodest and would cause men to lust after her. “If I didn’t change my clothes he said I was willfully disobeying God, I was denouncing Jesus,” Maartens explained. She began wearing baggy T-shirts and jeans that were two sizes too big, and stopped using makeup. They argued a lot behind closed doors over these and other issues, but after awhile, Maartens, who is naturally assertive and outspoken, stopped trying to debate her boyfriend. “I felt constantly condemned, he made me think that having the thoughts I did were wrong,” she said. Morris wasn’t good at time or money management, so Maartens got his account information and logged in and paid his bills for him. “He’s never worked a real job or had real responsibilities in his life,” she said. “To him working is to have someone else, in the name of Jesus, give him money,” referring to the Church of Wells’ reliance on “love offerings.”

Instead of studying for classes, Morris would spend hours memorizing the bible or praying in his closet through the night, both Maartens and his former roommate recalled. “He wasn’t a great student by any stretch of the imagination,” Maartens said. “He was constantly sharing why his professors were wrong, why the pastors at church were wrong. Everyone was wrong unless you were Amish or Leonard Ravenhill, unless you were a complete extremist you were just wrong.” But few, Maartens included, doubted the strength of his convictions: “I fully believed Sean loved Jesus and wanted to honor and glorify him in all that he did, and he wasn’t going to do it halfheartedly,” said Jeremy Echols, a friend who has since lost touch with Morris. “Sean came across as very sincere in his faith but extremely conservative,” Lee Foster, another fellow religion major, remembered.

Reed, who majored in religion and philosophy, took three courses with Morris, and remembers often cringing with embarrassment for him in class discussions. “When he started speaking it would kind of lower the temperature in the room,” Reed recalled. “His comments would suggest that what we were doing in class was pointless, because, in his thinking, if you just look at this verse of the Bible, it solves it all. There’s nothing to think about.” The interruptions were frustrating to other students. “Nothing would get done in class. It would just be dialogue between him and the professor, and at 9 a.m., you really don’t want to deal with that,” Foster said.

The most memorable incident, the one that gave Morris the nickname “9-to-10 Sean,” occurred in an environmental ethics class one afternoon in Spring 2007 when students were discussing the root causes of environmental crises, and the conversation turned to ecofeminism and patriarchal modes of thinking. “Sean took this as his opportunity to defend the patriarchy. He tried to explain why, based on the Bible and just common sense, men were supposed to be dominant and women were supposed to be submissive,” Reed said. As evidence that men were superior to women, Morris offered up his opinion that he could “beat up any woman,” Reed recalled. That elicited gasps from his classmates, who were quick to point out that that was likely untrue, and so Morris revised his position: “9 out of 10 girls can’t beat me up,” he said, recalled Keith Gustine, another classmate.

“I was flabbergasted,” said Morgan Caruthers, who is now a pastor in Austin, and was sitting three seats away from him during that incident. While other Baylor students share the view that women should be submissive and not hold leadership positions within the church, Caruthers found Morris’s delivery especially unpalatable. She had several other classes with Morris and said she was consistently struck by his lack of intellectual curiosity. “What stood out for me, especially in that class, was how unwilling he was to engage in any conversation if he didn’t agree with it. He never realized that even if you don’t agree with where a conversation is going, something can still be learned by having it.”

Maartens, who wasn’t aware that Morris conducted himself this way in his classes or held such extreme views, broke things off with him in February 2008, soon after returning from a ten-day trip to Nigeria to visit his parents, where, twenty months into their relationship, they kissed for the first time. (At Morris’s insistence, when they went swimming in the ocean on that trip, Maartens wore long board shorts and a T-shirt.) Morris had already bought an engagement ring but had yet to propose, and Maartens suddenly realized one evening in February following what should have been a romantic date that the relationship needed to end because Morris was not the right one for her. “A switch just flipped in my brain,” she said. Morris was devastated, and alternated between sobbing and pleading with her to reconsider. And then he threw out a few manipulative barbs: “He told me ‘you’re disobeying the Lord if you break up with me,’” she recounted. “He said I was gong to be renouncing my faith if I didn’t marry him.” A few days later Morris texted her, “I would rather see death than live a life without you,” leaving Maartens to worry that he might hurt himself. At the time Maartens, a social work major, was interning at the Advocacy Center For Crime Victims & Children. “What’s amazing to me is that I was working at a center that helps people going through abusive situations and it never occurred to me I was in one myself,” she said. Now a successful recruiter in the oil and gas industry in Houston, it took Maartens several years to get over how Morris had made her feel. Her well-loved copy of The Subtle Power of Spiritual Abuse is filled with underlining and marginalia (“ouch!” “so true!” “like when I wouldn’t repent”), and she said it enabled her to get over the relationship and learn to trust again.

Morris coped in a different way, by flinging himself into his friendship with the two students with whom he would found the Church of Wells, Ringnald, and Jacob Gardner, a younger McClennan Community College student whom they met at Antioch. “That relationship went from zero to sixty in 20 seconds,” recounted Jeremy Echols, who became good friends with Morris in 2006 because both felt a lot of what was going on in various churches wasn’t biblical. But, once Morris’s friendship with Ringnald and Gardner began to gel, Morris stopped coming around as much. “Sean became very infatuated by some of the doctrinal positions Ryan and Jake held,” Echols said, and would staunchly insist that the King James Version was the only acceptable translation of the Bible. And Echols felt perturbed by his interactions with Ringnald and Gardner: “It was hard to have a conversation without them very intentionally bringing up things they knew I disagreed with, in a very contentious way,” Echols said.

Unlike Morris, Ringnald appeared to be a more typical freshman at Baylor. The 2004 graduate of Trinity Valley School in Fort Worth rushed Kappa Sigma, played club tennis, and majored in speech communication. He was well liked by his fraternity brothers who gave him the nickname “Ringo” and appreciated his infectious enthusiasm and natural charisma. One of Ringnald’s former fraternity brothers recalled that Ringnald always did things to the extreme—when he played disc golf, he accumulated dozens of discs, when he started dipping tobacco, he did so constantly, when he started gambling online, he racked up debts. So, when he gave himself over to fervent, complete devotion to the Lord during his sophomore year, his friends thought it was a passing fixation too. “He always had obsessions, so we just thought this would be a phase,” his fraternity brother said. “If it is one it’s a much longer phase.”

An avid partier his freshman year, Ringnald gave up drinking, tobacco, and dating once he devoted himself to religion. He began keeping strange hours and attending fewer Kappa Sigma functions. His bubbly personality and sense of humor seemed to melt away too. “Now I get the sense he’s really somber and sober, the exact opposite of the Ryan Ringnald that we met our freshman year,” his fraternity brother said.

Ringnald and Morris graduated from Baylor in 2008. Without the structure and demands of college, their religious fervor intensified. They traveled and preached on the street for two years before amassing a handful of followers and moving their tiny church to Arlington. In 2012, they moved the group for financial reasons to Wells, a town of 792 people located between Lufkin and Jacksonville, where their fervent evangelism has not found a warm welcome, particularly after the death of Baby Faith in May 2012 and the arrival of Catherine Grove from Arkansas in July 2013. Grove, 27, left for Wells without a word to her family about her plans, and her parents have been trying without success over the last eight months to see their daughter outside of the presence of the church’s elders, as Morris, Ringnald, and Gardner now refer to themselves.

Morris’s classmates found news that he was caught up with something like this both surprising and not. “We thought Sean was harmless. We never dreamed that this was going to happen,” Reed said. Foster, another classmate, said, “If I had to pick the one person I had known or interacted with who would end up in something like this, it would be Sean.” Ringnald’s fraternity brother said that he and other members of his pledge class are deeply saddened by the shape their friend’s life has taken. “I feel bad that Ryan’s in this situation. I wish that this had not happened to him and his life, but I feel even worse for the people he’s affected,” he said.