This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

If Karen Silkwood hadn’t discovered that the bologna in her refrigerator was contaminated with plutonium and then died in a mysterious wreck, I would never have ridden between San Angelo and Eden with A. O. Pipkin, Jr. Pipkin is the sole owner and employee of the Accident Reconstruction Lab of Dallas. His business is investigating traffic accidents to determine why and how they happened. Although the accident he was now investigating had occurred only five days earlier, Pipkin frequently finds himself called on a case weeks or even months after the event; yet his investigations rarely suffer from such delays. He does not depend on eyewitnesses, even when they are available. Over the years he has come to regard police accident reports as interesting curiosities but far from the gospel. His clients are insurance companies, truck lines, attorneys trying personal injury suits, and, in the case of Karen Silkwood, a labor union.

Pipkin’s specialties are head-on collisions (“I love ’em”) and wrecks involving trucks. The wreck near Eden had been a head-on crash between a truck and a late-model Cadillac. The truck driver was not badly injured but the occupants of the Cadillac, an elderly man and his wife, were both killed. Though no damage suits had been filed yet, the food corporation that owned the truck had hired Pipkin to investigate just in case. His credibility and skill as a trial witness are as important in his work as his expertise in investigation. In twenty years of work he has investigated over 2000 accidents and testified in more than 300 trials.

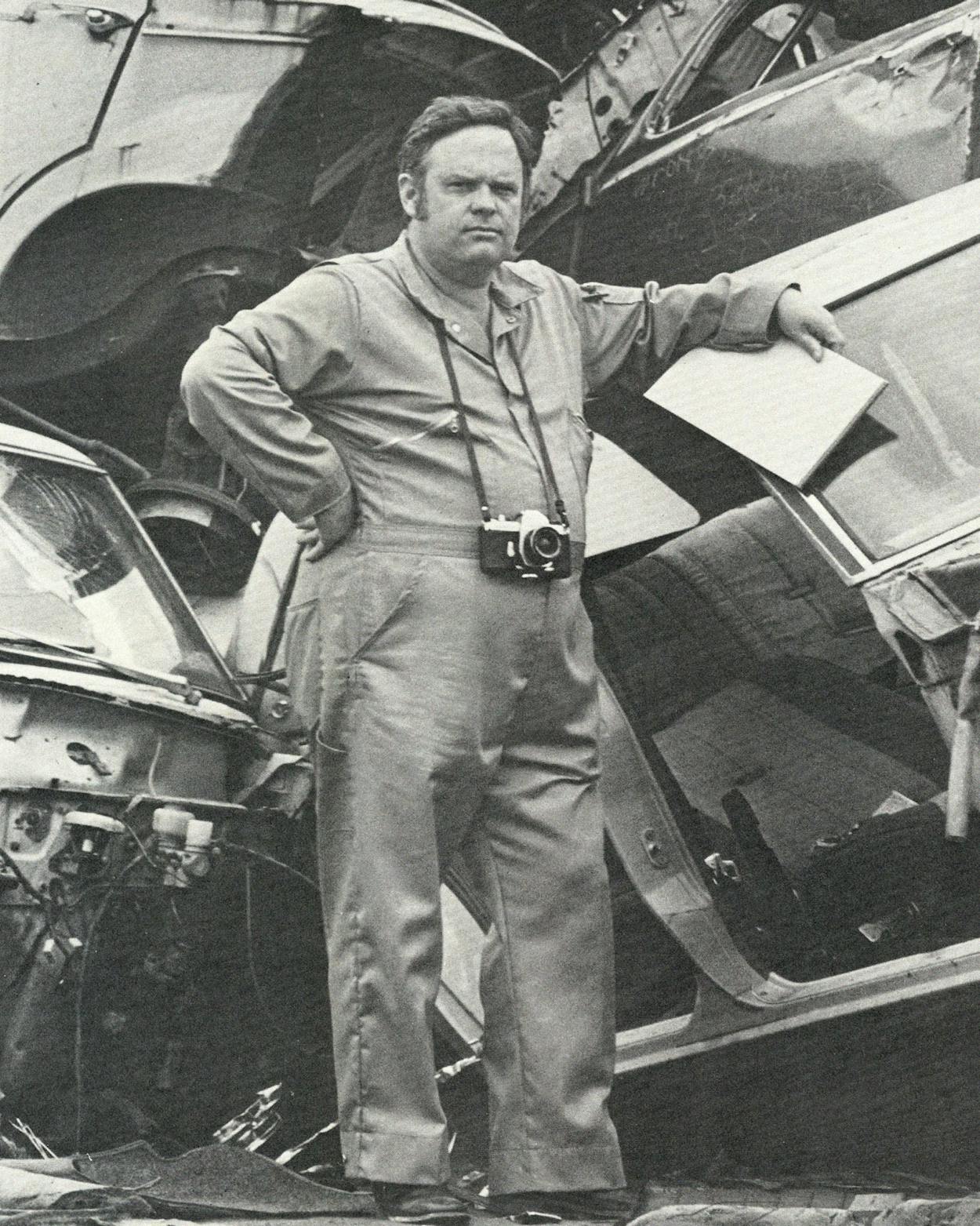

Pipkin and I flew from Dallas to San Angelo, rented a car, and drove over to the truck dealership that was storing the wrecked truck in its back lot. A. O. carried all his equipment in a fat gray attaché case fitted with a single piece of thick foam rubber in which he had cut small compartments to hold the tools of his trade: a Pentax camera and lenses; a pocket transit-compass which he used to record the angles of intersections and the uphill or downhill grade at the scene of accidents; a tape measure; a folding tripod; a stopwatch for measuring acceleration times; something he called a “clampod” which served the same function as a tripod but clamped onto tree limbs or windowsills or whatever else was handy; a Rola-tape for measuring distances across pavement; and, folded neatly in the top of the case, a bright orange jumpsuit Pipkin dons when he has to crawl under, over, or through wrecked vehicles. Pipkin is about 5’10”, round-faced, round-bellied, and thick-legged. In the nylon jumpsuit he looks a little like an orange balloon.

We were first met at the dealership by a tall, palsied man who was chewing on the short stub of a thin cigar. He was a photographer who eked out a living by taking pictures at the scene of wrecks on West Texas highways. When we examined the truck I saw a sticker he had placed on the passenger door: ‘‘NOTICE. Pictures of this accident were taken when and where it happened. If you want pictures call. . . .” He wanted Pipkin to see his photographs of the wreck, which were so overexposed as to be nearly useless except for showing the final positions of the vehicles. “There weren’t any skid marks, either, that I could see,” the photographer said. The insurance adjuster who had arrived on the scene before the wrecks were towed away also reported there were no skid marks. “We’ll see,” Pipkin muttered to me. “Can’t tell a damn thing from these pictures.”

Then the manager of the processing plant the truck belonged to came to take us around back so Pipkin could examine the wrecked vehicle. The manager was a dapper, gray-haired man who seemed annoyed not only by this wreck and its resulting inconveniences to him and his company, but also by life itself. “Just what does your plant do?” Pipkin asked him. “We’re in the gut business,” the man replied curtly.

As we walked back to the truck, the manager filled Pipkin in on the details of the wreck. It had happened on a Thursday afternoon. The track was empty and the driver was going south to pick up a load of animal parts for rendering. When he was just south of Eden, little more than an hour away from San Angelo, he saw the Cadillac coming toward him. It drifted over into his lane. He saw the elderly driver staring back over his right shoulder at a farmer plowing a field. The truck driver tried to pull far to the right but the two vehicles met on a short bridge and the guardrail kept the truck from moving over far enough. “It took ’em 45 minutes to cut those people out of the Cadillac,” the manager added. “I wish we could get all this investigation nonsense cleared up so I can get a new truck. I’m leasing one now and that’s for the birds. Too expensive.”

The truck had been in a wreck all right. A White Western Star conventional fiberglass-bodied truck, it was sprawled at the back of the lot behind the dealership building. The top half of the cab was generally undamaged, but the bottom half was twisted and bent in such crazy patterns that it looked as if the axle, fenders, and frame had all gotten drunk and fallen in a heap. The fiberglass cab was not dented or crumpled like metal but ripped in ragged, wavy lines like torn cardboard.

Pipkin took a few pictures when we were still fifteen yards from the truck. Then having walked around it quickly from close range, he checked the engine numbers and license so he could prove in court that the truck he inspected had indeed been the truck in the wreck. Then he asked the manager if he could get the truck yard’s wrecker to hoist the front end of the truck. Pipkin wanted to check the underpinnings to see how they were damaged, and to check for parts that might have left gouge marks in the road. While two men fiddled with getting the diesel wrecker started, Pipkin came over to me and said, “This wasn’t no direct head on, I’ll tell you that right now. Right now I’ll bet they didn’t overlap more than a couple of feet. Come here, let me show you something.” We bent down near the left front of the damaged truck. “See those bolts there? Those are called pulley bolts because they hold the fan belt pulley to the drive shaft. If these vehicles had hit head on fast enough to do this much damage, those bolts would have been severed. Now look at the frame. See how it’s all bent way back on this side but hardly bent at all on the other side? Same thing with the axle.”

He walked a few steps down the driver’s side of the truck motioning me to follow. He pointed out brown stains on the tires on that side; the Cadillac’s radiator had exploded at impact and radiator fluid had left the stains. He pointed to dents and slashes in the driver’s door and in the fuel tank behind the door. “See?” he said. “No way that Cadillac’s gonna get back here to make those if they’d hit head on.” Then he pointed to some thin slashes about six inches long in the outside tire of the first set of wheels. “Look at those right now,” he said, “and just remember them.”

In the meantime, the wrecker drivers had gotten the truck hooked up and hoisted the front end high enough off the ground so Pipkin could see the underpinnings without having to venture too far underneath. But he found little of interest. He walked back over to me. “We’ll know for sure when we see the Cadillac,” he said. “But I’ll just bet you what happened was they hit more or less left headlight to left headlight, no more than a foot or two of contact. Then the Cadillac spun around and hit the driver’s door and fuel tank and made all those dents. That’s also why those radiator stains are on that side.”

“But,” I said, “there’s damage on the passenger side of the truck too.”

Pipkin nodded his head. “Sure there is. This thing took place on a bridge. My theory says all that happened when the truck hit the railing.” He turned back to the truck and took about ten pictures from various angles and then took one shot of an identical but undamaged truck that was standing in the yard. “Come on,” he said finally. “Let’s get down to Eden and look at that Cadillac.”

The highway between San Angelo and Eden is wide, level, and, this day at least, not much traveled. For all of which I was thankful. It isn’t that A. O. Pipkin’s driving gives special cause for alarm, but it is disconcerting—at the very least disconcerting—to ride along with a driver who makes comments like “See that truck at the crossroad up ahead? If he pulled out right now, we wouldn’t have time to stop.” Or when a semi started tailgating us Pipkin would comment, “Look at that idiot. If we had to stop, he’d plow right into us. He’d turn this car into an accordian.”

In 1967 Pipkin reviewed the investigation of the wreck on U.S. 90 between Biloxi and New Orleans that killed Jayne Mansfield. That was his best known, though not necessarily his most interesting, case before the recent Karen Silkwood affair. Silkwood was an employee of Kerr-McGee’s plutonium plant near Crescent, Oklahoma, about 30 miles from Oklahoma City. She believed that the plant was unsafe and that the plutonium rods it made for nuclear reactors were dangerously below standards. She was gathering evidence for the Oil, Chemical, and Atomic Workers International Union of unsafe practices at the plant. In the process she discovered that she was becoming contaminated with plutonium in ways she couldn’t explain. On three successive days she found herself contaminated when she arrived at work. No mishap at the plant would explain this phenomenon, but a team of Kerr-McGee inspectors discovered traces of plutonium throughout her apartment. A package of bologna and a package of cheese in her refrigerator showed the highest level of contamination. No one could explain where this plutonium had come from. Extremely worried, Silkwood called union headquarters and asked an investigator to come to Oklahoma City. He brought along a reporter from The New York Times. On November 13, 1974, about 7:30 p.m., Silkwood was driving to meet them with a manila folder containing the information about plant safety she had collected, when her small car swerved off the road and crashed into a cement wing wall by a ditch. Silkwood was killed. The manila folder and its documents disappeared.

The Oklahoma police determined that Silkwood, who had been taking Quaaludes for her nerves, had fallen asleep at the wheel under the influence of the drug. The union hired Pipkin to make his own investigation. There were several things about the police report that didn’t make sense to him. First, Silkwood’s car had drifted off the road to the left, when normally, since highways are slightly peaked at the middle, a car out of control will drift to the right. Also the level of barbiturates found in her body was not enough to induce sleep; in his experience Pipkin has observed that most people are not sufficiently tired at 7:30 to fall asleep at the wheel.

After examining the physical evidence at the scene Pipkin disagreed with the police report about the angle her car had left the road and how it had hit the wing wall at the ditch. But his most important discovery came from Silkwood’s car, which the police hadn’t bothered to examine at all. Pipkin saw a large dent in the left rear fender and a smaller related dent in the bumper. The dents were fresh—no road film had accumulated on them. The police, confronted with this information, claimed the dents were made by the cement wing wall when the wrecker pulled the car from the ditch. “But, hell,” Pipkin told me, “those dents are concave. Now you tell me how a flat cement wall’s going to make a concave dent in anything. Besides, I took the bumper and fender to a laboratory. There are no cement particles in that dent. I think some car hit her from behind. That’s where the dent comes from.”

Pipkin discovered another bit of evidence while he was examining the color photographs he took of the wrecked car. The sides of the steering wheel were bent forward. An unconscious body upon impact bends the top and bottom of the steering wheel forward. When the sides are bent it means the driver was conscious, was holding the wheel, and had locked elbows against the crash. If this was how Karen Silkwood died, she could not have been asleep at the wheel. Investigations are continuing. Pipkin’s work on this case had made him jumpy enough that when I first contacted him about this story he thought I might be a private detective posing as a reporter to check him out.

Pipkin grew up in Albuquerque, New Mexico. He studied engineering at the University of New Mexico for two years before quitting in 1950 at 21 to join the motorcycle division of the Albuquerque Police Department. The department had just then introduced mobile radios, but the old hands in the motorcycle division didn’t like the new-fangled devices and kicked them in so they could patrol their beats without being bothered by calls from the dispatcher. That left the rookie Pipkin the only motorcycle cop with a working radio and therefore the only person available to send to the scenes of accidents. He started carrying a camera and selling pictures of wrecks to the newspaper and to lawyers. He took a six-weeks course in accident reconstruction design for police officers. By 1955 Pipkin had investigated enough wrecks, taken enough pictures, and testified at enough trials that he left the police department and started his own accident investigation business.

He worked hard to make ends meet until about three years ago when a lawyer happened to comment that there was no one doing his kind of work in Dallas, where there are more people than in the whole state of New Mexico. Since moving to Dallas, his business has blossomed and he has had a chance to get a degree in automotive science from Eastfield College and to attend truck-driving school to learn how to drive the big rigs whose accidents he investigates so frequently. This fall he hopes to enter SMU to resume the college education he interrupted so long ago. He already has the subject in mind for his master’s thesis in engineering.

Pipkin “likes” head-on crashes because, although they would appear to be the simplest accidents to reconstruct, they are more often the most challenging. “If two cars hit head on, most people, the police included, just assume that the car that ended up in the wrong lane was at fault. But that’s not always the way it happens. Now suppose,” Pipkin said as he pointed out the windshield at the road ahead, “we suddenly saw a car headed right at us. The right thing to do is swerve to the right and take your chances with whatever’s by the side of the road. But most people do this.” He swerved suddenly to the left toward the oncoming lane. “It looks like the safest place—but what happens is the idiot in the wrong lane suddenly wakes up to what he’s doing and he instinctively swerves back into his lane. So the two cars swerve suddenly and still hit each other. But now the innocent car is sitting in the wrong lane. Proving that’s what happened is really fun.”

Since most people when they swerve to avoid a crash also jam their brakes, the first evidence Pipkin looks for is skid marks. Interpreting them, however, is a tricky matter, since, in cases like this, either one wheel makes a mark, or else one mark is very heavy and one is very light. Since a vehicle’s weight is thrown to the outside when it swerves, common sense would say that the outside wheel, now under greater pressure, would make the heavier mark. But common sense would be wrong. When the outside wheel is under this added weight, the wheel continues to roll in spite of the brake, whereas the inside wheel, under less weight, locks tight and makes the skid mark. Since Pipkin can prove which wheel made the skid mark, he can show the position of the whole car and the lane it was in at the beginning of its swerve.

But what if there aren’t any skid marks? Then Pipkin examines the gouge marks made in the asphalt during the accident. Gouge marks are made as the vehicles reach their maximum engagement and begin to bounce back from one another. The marks are deepest at the vehicles’ maximum point of impact. Pipkin examines the bottoms of the wrecked vehicles to find the bolts, bent braces, or twisted pieces of frame that made the marks. By this matching he can determine the exact position of the cars at impact. The angle of collision will show the path the vehicles were following before they hit.

In one case several years ago in New Mexico two men who half an hour or so earlier had been drinking in the same bar ran into each other head on. Both were killed, the cars spun off the road, and there were no witnesses. All the evidence indicated that the wreck had happened in the westbound lane. But which car was traveling west? A lawyer representing one man’s survivors hired Pipkin. In order to present his evidence, Pipkin photographed each car from above and cut out the outline of each car. Fitting the outlines together revealed the relative position of the cars at impact. Together they made a wide V. The road at the site of the collision was slightly curved with the westbound lane on the outside. When the cutouts of the wreck were placed on a diagram of the road, the angle of the V fit to the curve of the road only when Pipkin’s client’s car was westbound. If that car had been eastbound, the two cars would have had to enter the wreck from the farmer’s field at the top of the curve. Pipkin’s evidence and his presentation of it settled the case. “It’s still my favorite investigation,” he told me as we neared Eden. “The problem looked so difficult, but the solution was so simple and so convincing.”

“What about this case?” I asked. “How do you know the truck wasn’t in the wrong lane and tried to swerve back?”

“Well, I don’t think so—because of those marks on the passenger side of the truck. If he’d been swerving back into the right lane I think he’d have gone on over the bridge. But we’ll find out for sure before all this is over.”

Eden, while not a place with the beauty of its namesake, still seemed a peaceful and inviting enough little bulge along the highway. Folks spending the day in town gather in the drugstore where they sit in folding chairs around machine or coffee they pour themselves from a pot on a counter against the wall. A. O. Pipkin and I sat around and had a Coke ourselves, then went looking for the GM dealership where the wrecked Cadillac was supposed to be stored.

The manager of the dealership saw us driving around among the cars stored behind his building. He came up to us as soon as we had parked and got out of the car. He was a tall, light-haired man with a thin face, and was dressed in a white shirt, dark slacks, and black cowboy boots. Pipkin told him he wanted to see the Cadillac.

“It’s in the warehouse,” the car dealer said. “But another insurance man came and looked at it just the other day.”

“I know,” Pipkin said, “but I sure would appreciate having a look at it, too.” Pipkin handed the man his card.

“I don’t know,” the car dealer said. “I’m awful busy and it seems like if that fella saw it the other day that would be enough.”

“I’d still like to see it.” And then Pipkin added, “You know, that’s what makes lawsuits—difference of opinion.”

“Well, I guess it’s all right.”

We followed him a few blocks down a dirt road to a corrugated metal building near several others like it that were used as cotton warehouses. The dealer unlocked and rolled back a large sliding door. The long warehouse was dark and virtually empty. Two cars were parked to the left of the door we had entered. In the darkness at the far end, just in front of another sliding door, lay the Cadillac. The front sagged and collapsed in on itself so that the car looked like one of Claes Oldenburg’s soft sculptures. It still emitted an acrid smell from the diesel fuel that had spilled on it during the wreck. Small specks of glass clung to the vinyl top. The handle was shorn completely off the door and a maze of crumpled metal jutted into the front seat. “It took an hour to cut them people out,” the dealer said. “I just went around picking up pieces all over the highway. Just pieces.”

Pipkin had already taken his pictures, making sure to get one of the license plate for positive identification. He called me over and pointed out some rubber marks on the front bumper. “They came from the truck’s back tires, see, because the streaks run side-to-side rather than up-and-down like they would in a direct head-on crash.” He pointed out how the frame and axle on the left had been twisted one way when the car hit straight on and the right side twisted another way from hitting the side of the truck as the car spun past. Pipkin pointed to the right front corner of the hood. It was bent back like the corner of a page in a book. “That’s what made the slashes in those rear tires I pointed out to you. See? The car had to swing around to do that.” I went over and looked at the bent corner. There were heavy black rubber stains along its edge. “They hit left headlight to left headlight,” Pipkin said, “then that car spun around and its right front made all that damage in the truck’s side.”

“No, sir,” the car dealer said. He had stood quietly during Pipkin’s examination, but now his original annoyance returned. “That wreck couldn’t have been more head on. You can tell just by looking at that car. Come on out of here now. I’ve got work to do.”

“That’s what makes lawsuits,” Pipkin said as we walked out, “difference of opinion.”

We got back into the car to drive a couple of miles further to the scene of the accident. “I never argue with guys like that,” Pipkin told me. “But there’s no other way this could have happened. It’s important, too, because if it was a direct head on then that would mean that the Cadillac had been in the truck’s lane a lot longer. They might argue in court that the truck driver should have seen the danger sooner.”

We found the scene without any trouble. The road was straight at that point and almost level. The bridge, marked only by the short guardrails on both sides of the road, spanned a tiny stream that was almost dry. On one side of the road was sheep pasture; on the other was the field a farmer had been plowing the day of the accident. The truck had left a clear set of skid marks which, swerving to the right, led to the gouge marks that marked the accident as happening almost in the middle of the truck’s lane. Pipkin was delighted, not only because he had been right about the lane in which the wreck had occurred, but also because he had found skid marks when the photographer and the insurance adjustor had found none. “You can find more evidence a few days after the accident than at the scene. There’s too many people around, litter and fuel spilled all over the highway. Wait till all that gets cleared out and that’s when you find stuff everyone else misses.”

He took pictures of the scene. Then he got his tape measure and Rola-tape out of his kit and measured the distance of the gouge marks from the edge of the road, the length and position of the skid marks, and the width of the road and opposing lanes at that point. Once when we were out near the beginning of the truck’s skid marks, Pipkin walked off the additional distance the truck would have traveled during the driver’s reaction. Then looking back past the point of the accident he pointed out the spot up the road when the Cadillac had crossed irretrievably into the truck’s lane. “When the car was there and the truck was here,” he said, “there was nothing anyone could do to avoid the accident. Those people in the car were dead from that point on.”

I looked down the road. The points he was talking about were very far apart, perhaps 200 yards. Two hundred yards to go and they were as good as dead. Walking back, I saw something by the side of the road flash in the sun. It turned out to be the handle shorn from the door of the Cadillac. I thought of the mangled crush of steel I’d seen in the car’s front seat and thought about those 200 yards and it spooked me. I threw the handle away and wiped my hand on my pants leg.

We drove back to San Angelo with Pipkin in an expansive mood. “I’ve lost some clients because I wouldn’t report things their way,” he said. “But you can’t ever let that influence you. I always think that if I can figure out what happened, somebody else smarter than me can figure it out, too, and he’s gonna make a mess of me in cross-examination. It doesn’t matter how good I am reconstructing these accidents if no one believes me in court.”

Waiting in San Angelo for the plane to Dallas, we shot some pool. Pipkin proved to know as much about collisions between ivory balls as between motor vehicles. “All it takes,” he said, as he pocketed the nine ball, “is applying the laws of physics and common sense.”

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads