The following is an attempt to make insulation sexy. A fool’s errand, I know, but hear me out, because I’ve actually discovered that R-values can make your heart flutter.

I became well acquainted with R-values—a measure of resistance to heat flow—a couple of months ago, when I had three experts (one a thermal-imaging specialist, one from TXU, and one from the Environmental Protection Agency) evaluate my house’s energy efficiency. Now that I was serious about going green, I had to know where to start. The news from my auditors, however, was brutal: My quaint fifty-year-old two-story was about as environmentally incorrect as a house could be. It was leaking warmth in the winter and allowing heat to penetrate in the summer, making both my heater and AC work overtime. My attic, they told me, rated a dismal R-9 (instead of the recommended R-49), my French windows a troubling R-1 (together they amount to a wall, and walls should ideally be R-18), and my floor had basically no R-value. If I was going to reduce my carbon footprint, I would first have to address this woeful energy seepage.

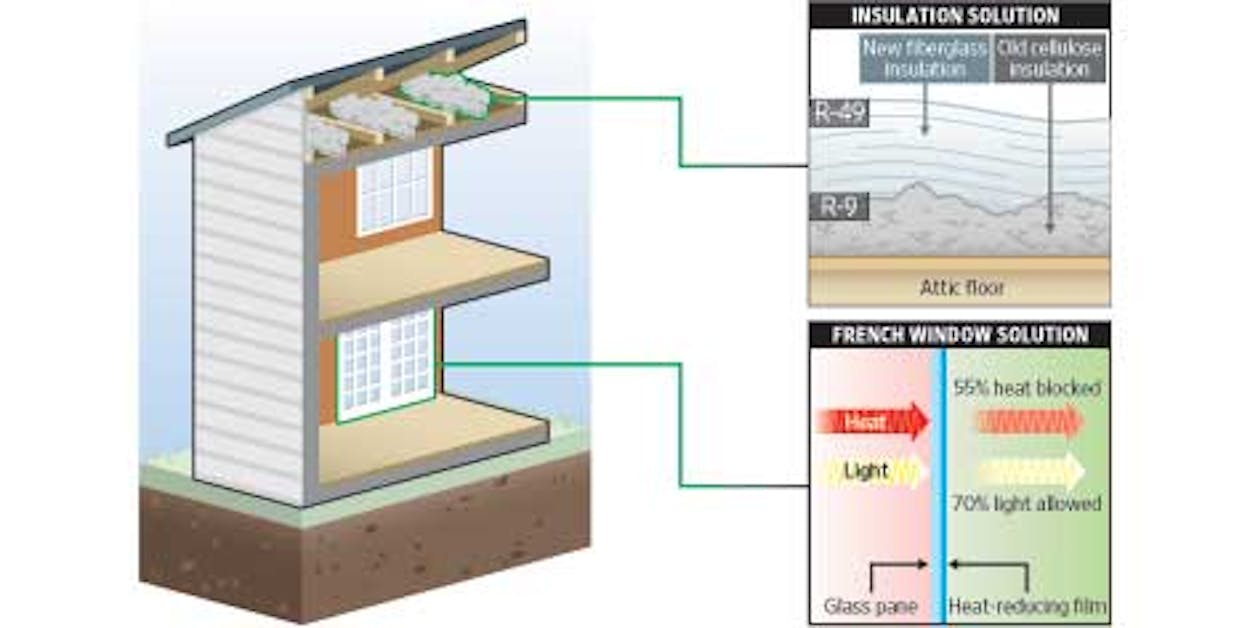

So I decided to start with my attic. My thermal-imaging guy, Tom Mayfield, recommended I call Matt Foerster, of 4 Star Insulation, in Richardson (your energy provider can make similar recommendations for you; the company itself is less important than getting the right insulation). He advised me to take the attic to a full R-49, no half measures. As I researched online, I found that today’s two most common insulation options are cellulose and fiberglass. The controversy I read about each—fiberglass may be carcinogenic, though in insulation form it isn’t necessarily harmful; cellulose is composed of recycled paper and may be a fire hazard—was enough to excite the talking heads on Hardball, so I went with Matt’s opinion and chose fiberglass, which is used in a majority of new homes these days. Getting to an R-49 required that we add sixteen inches of the stuff to the two inches of already existing cellulose (I might have had him remove the existing cellulose, then add even more fiberglass, but that would have been more expensive).

As a home-office kind of guy, this was all a bit of a pain: Matt’s crew had to drag a big pneumatic hose through the front door and up the stairs to a spare bedroom, where our only attic access is, then turn on a blower that sounded like what the first moments of D-day might have. Never mind: I went for my daily jog, then happily paid Matt a mere $632 for the entire enterprise. This, he told me, would save me about 20 to 25 percent on both heating and AC, which translates to at least $75 a month and $900 per year. I haven’t seen my new bills yet, but I’ve already noticed that the heat comes on a lot less.

Now that I had a snug toboggan cap on my house’s “head,” what about the rest of its frame? My floor, said Matt, wasn’t really an issue in our climate. The ground rarely gets cold enough for long enough for crawl space insulation to make much difference. But the French windows—now, those were a problem. “Energy efficiency in Texas is all about that AC and how well you can keep hot air out of your house,” he said. And my windows, I’d learned, were responsible for at least 25 percent of my home’s unwanted heat loss or gain.

This meant more research. I got a fast education from the Department of Energy (eere.energy.gov) and consulted again with my cohort of auditors. The most energy-efficient solution, it appeared, would be to replace our windows with glazed, double-paned versions, which in our case would have to be custom-made because of the age of the house. But then there was the price tag: at least $9,000. Sure, we could afford it, but was it practical? Talking it through, my wife and I concluded that (a) we probably wouldn’t be in the house long enough to make such a change worth our while, and (b) given that we live in Highland Park, a one-hundred-year-old Dallas enclave with very high land values but very old homes, it was likely that when we sold our house, it would be to a contractor, who’d pay a premium for the dirt and promptly bulldoze our dwelling to replace it with something more up-to-date.

Since we didn’t want to shell out 9K only to see our efforts leveled in, say, five or six years, we opted for baby steps. First we would double-pane only the worst offender, a box window that sits on the southwest corner of the house and that, in summer, allows 100-degree sunshine into the kitchen from 2 to 8 p.m. After taking a couple of bids, I gave the task to my multipurpose handyman, Jake Jaco, who’s done good work for me before and has the best handyman name I’ve ever heard. Cost: a reasonable $1,200. The payback of that window alone will probably be huge because of the peculiar fifties shape of our home: Our downstairs, which comprises the kitchen and the dining, living, and den areas, is really like a one-room-deep rectangle, meaning that all that sun pouring into the kitchen has likely always affected the heat throughout the 1,300-square-foot first floor.

But we still wanted to do something with the French windows. At the suggestion of Jon Bennett, the TXU auditor, I contacted Kurt Howell, who runs a local company called AmeriTint. Kurt specializes in tints and films that can significantly reduce the amount of heat that passes through any window without losing much of the light. This was a central concern for my wife and me, because, as inefficient as our home is, it does have an abundance of natural light, which is not only pleasing to the eye and the psyche but also, in its way, an energy saver, since we don’t have to use our lights as much.

We had Kurt install a preview of four films on the windows in our living room. The light allowed by the various samples ranged from 42 percent to 70 percent; the heat transfer reduction ranged from 35 percent to 55 percent. I confess to some trepidation; even 70 percent sounded as if we were doomed to a life of darkness. But when he had the film mounted—it’s a kind of ceramic-metal alloy that is cut to size and then applied to the interior of the pane, like transparent tape—I was shocked that my eyes could barely detect a difference, especially with the 70-percent-light-allowed, 55-percent-heat-blocked version.

I was so impressed, in fact, that this is probably what we’ll have installed on all the French windows, both stories, on the south side of the house. Kurt and I discussed the north side only to discover that most of it had already been double-paned by the previous owners. (An object lesson in greening: Know exactly what you’re starting with before you throw the plastic around.) Also, the north side of our home is well protected by eighteen-inch eaves and a large sun-blocking live oak. We’ll tackle this change in the next few weeks; Kurt tells me it will take a few days and cost between $2,500 and $3,500. His conservative calculation is that adding the film will reduce my annual AC costs by 22 percent, which comes out to almost $750 in savings.

In all, I’ll have spent roughly $4,500 to better insulate my house, but I expect to earn that back in three or four years, then actually make money on this green venture. Plus, the effect on my carbon footprint is noticeable (see “Progress Report”). Think about it. When’s the last time you made an investment that paid back like that—and benefited not only you but everyone else? Now, tell me that isn’t sexy.

Progress Report:

This month’s effect on my carbon footprint, wallet, and happiness.