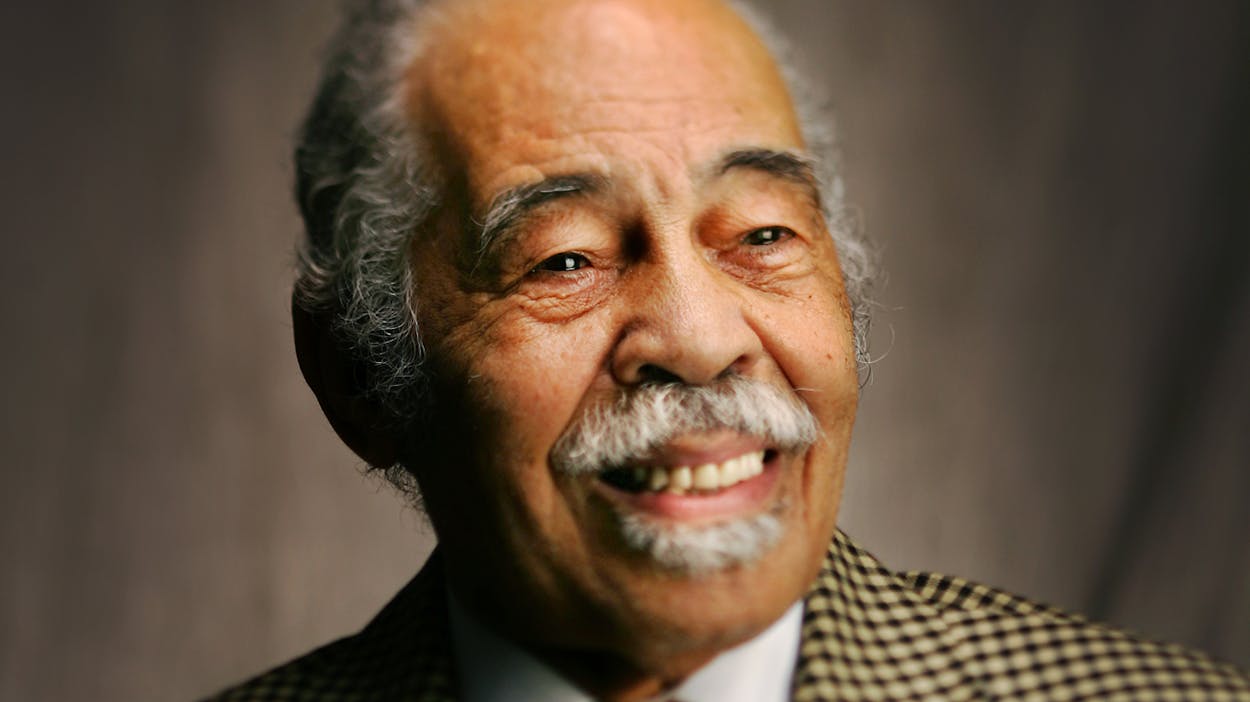

Thomas Freeman (Photograph by Chris Schneider)

Just after finishing his doctorate, around 1947, a 27-year-old teacher named Thomas Freeman got a job working at Morehouse College in the religious studies department. He didn’t know it at the time, but one of the teenage students sitting before him would change history. The student was a sociology major who didn’t engage much in class, and at the end of that somewhat unremarkable year, Freeman left for another job.

Years later, Freeman moved to Houston, where he would teach religion, philosophy, speech, and debate for more than seventy years at Houston Community College, Rice University, and Texas Southern University. One day he was sitting at a table with a debate team he had been coaching, when Martin Luther King Jr. walked in. Freeman’s table watched in awe as King walked up to their coach, stuck out his hand, and said, “You don’t remember me, but I remember you. You taught me.” Freeman was flabbergasted. King then went on to describe the course Freeman taught at Morehouse.

At 94, Thomas Freeman has become accustomed to run-ins like this with his former students. “I cannot overestimate the impact and influence Dr. Freeman had on my life,” said Barbara Jordan, the first Southern black woman elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. Other students, like Senator Rodney Ellis, have also risen to prominence, so much so that when Denzel Washington wanted a model for the 2007 biopic The Great Debaters, about Wiley College, in Marshall, going to debate the reigning champions at a white university, he was told to track down Freeman.

On March 24, just after he had returned from Paris, France, with his debate team, I asked Freeman about his upbringing and for some tips on public speaking.

You are known for your way with words. How did you become interested in language? Were your parents big readers? No, but my parents were interested in educating their children. I’m from a band of fifteen, twelve of whom grew into manhood. My mother and father—neither finished high school. But they wanted education for their children. So my father provided advanced education for all the children. They all went to the college of their choice, except me. I had to stay in Richmond, Virginia, because I was too young to leave home. I was a fourteen-year-old kid when I started college. I finished at eighteen or nineteen and then left home.

How was your father able to get all those kids into college? My father was a wholesale produce merchant—the only black wholesale merchant in the state of Virginia—and therefore he had sufficient income to take care of the large family. We grew up during days of depression, but we didn’t know there was a depression.

What drew you to speaking? I’ve been preaching since I was nine years of age.

Are you still pastoring at Mount Horem Baptist Church? I’ve been pastoring for 63 years. Celebrating the sixty-third year next Sunday.

Are people more or less skilled at speaking today? More attention is being given to speech activities. I organized the interscholastic league in 1951 to provide the opportunity to young people. We had the interscholastic league sponsored by TSU and the southern intercollegiate conference that I established because we couldn’t go to white schools to debate and so in order to have that experienced we organized our own. And that lasted until ’57, I believe. And with integration, the need was no longer there. So we participated with the other schools. When I took Barbara [Jordan] to Baylor in 1954, that was the first time blacks had participated in forensics in the South.

I’ll bet you have a lot of stories from those days. Oh yes. Some are not so delightful. One of the experiences: At one tournament, at the final event, was a banquet, and students who survived the after-dinner speech contest would speak at the banquet. Two of our students survived, and that was the first time blacks had ever spoken at a university or college closing assembly of debate. And the former coach of the debate team who had retired stood up after our students spoke and said, “Twenty years ago, I wrote and defended a dissertation in which my thesis was that blacks were inherently inferior.” And then he added, “After listening to these two young people, I admit that I was in error.” You could hear a pin drop after he spoke.

What is your methodology when you start with a new student? I work with students on an individual one-to-one basis and deal with them in terms of where they are and where they would like to be. Over the years I’ve been able to sense things about students who have come my way, and I try to react to what is presented to me. Sometimes it’s almost intuitive, sometimes it’s the hand of God. I don’t know. But something emerges in my relationship with students and I’m able to feed into their lives in such a way that a significant difference has been made. At the outset, I couldn’t tell you what it was, but they will tell you the influence it has been on them. It’s personal encounters. And there are no barriers. They do not call me “Doctor,” they do not call me “Professor.” They may call me by my first name or nickname, “Doc.” And that ease of relationship contributes to growth and development.

How do you get to know your students? I have an open-door policy. Students come into my office all day long every day, and I deal with those who come in. They come in with varying kinds of problems, and I deal with those: some are financial, some are emotional, some are psychological, some are spiritual.

How do you handle someone who has a psychological problem with speaking—a stutter, for example? The fear of authority, that can be psychological, and you have to learn to get over that fear. And you learn best by appearing before an audience and being frightened to death! Many times I put students in situations they resent, but the situations bring out of them what they need brought out at that moment. And when they look back on it, they say, “I didn’t understand what you were doing, but I certainly thank you for it.”

I know that you had Barbara Jordan as a student. For four years!

How did you see her improve? I judged her at an oratorical contest when she was in high school, and that next year she found the debate team and joined it, and I worked with her on control of her voice and also on the attack of consonants, and I had to teach her stage presence.

How would you teach her to attack her consonants, or any kind of diction? Do you have the students practice tongue twisters as exercises? No special tongue twisters. If someone has difficulty with a c word or a k word, you have to repeat the word over and over again until you say it smoothly.

How do you teach people to organize their thoughts before they speak? Practice, practice, practice, practice, practice, practice. You learn to do by doing. Put them up on a stage and have an impromptu session.

So you would have somebody do an impromptu speech about a subject? That’s right. I have a fairly large group of debate students, but we do at least eleven events and we don’t have specialists. Everybody is trained in poetry interpretation, dramatic interpretation, extemporaneous speaking—all of them. And debate. We do several kinds of debate: we do Lincoln-Douglas debate, one-on-one, and parliamentary debate, which is two-on-two, and then public policy debate.

What do you do when someone is having those debates in practice and you recognize they’re not listening? I stop them then and call their name.

How do you teach them to have a more commanding presence? If you have experience with them, it’s not hard. You know a timid soul. I allow them to tape their materials before criticism and then listen to the criticism, and then retape it and listen to it, so they watch their personal growth and development through the tapes. And then we have a studio that students are able to come to with a mirror where they see their facial expressions and so forth.

How have you dealt with students who had stage fright? Breathing exercises.

What kind of breathing? Inhaling, exhaling, with emphasis on the diaphragm. I have them hold their hands over the diaphragm and feel themselves as they’re breathing so it becomes natural to them. It won’t be artificial.

What if they still don’t want to get up there? Do you force them? I don’t force them to get up there, but the request is so strongly stated that they dare not sit down.