On December 12, 2009, newly elected Houston mayor Annise Parker stood before a throng of supporters gathered downtown at the George R. Brown Convention Center. Beaming in a shimmery gold pantsuit, Parker, the first openly gay mayor of a major American city, triumphantly told the crowd, “This election has changed the world for the gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender community—just as it is about transforming the lives of all Houstonians for the better.” Among those listening raptly to Parker’s passionate words was a man in his early forties, dressed in full military regalia. With an angular face, short brown hair, glinting rectangular glasses, and goatee, he looked unassuming—except for his bow tie and crisp blue military uniform heavily adorned with medals, pendants, badges, and pins reflecting the rank of an Army brigadier general.

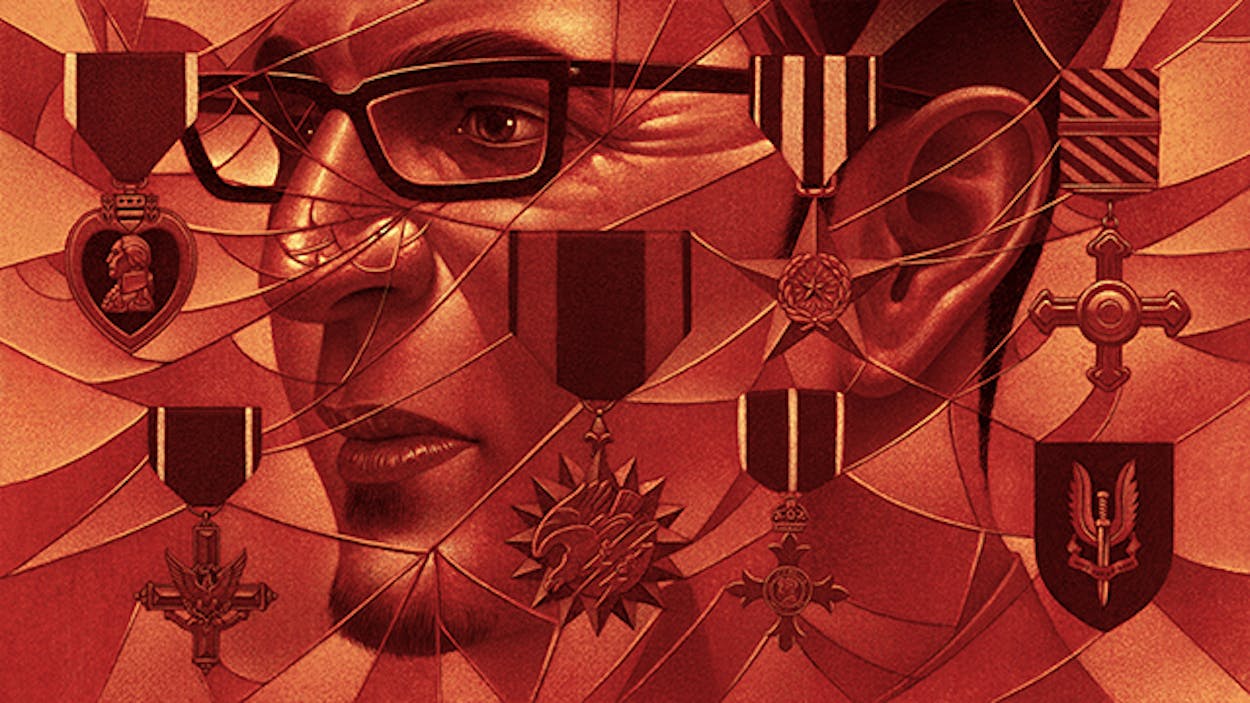

One photographer at the event, a former Marine Corps sergeant, noticed the man’s attire and grew suspicious of how his uniform violated a number of dress-code regulations. A brigadier general would never appear in uniform with facial hair, the photographer thought. Plus, the medals the man wore—a Purple Heart, Silver Star, Bronze Star, Air Medal, Flying Cross, and Distinguished Service Cross, plus five other U.S.-issued emblems mixed in with a Commander of the Order of the British Empire award and a British Special Air Services Crest—seemed conflicting and implausible.

The photos ended up online, where they circulated on numerous military-focused blogs. The man was decried as a despicable fraud, one blogger writing, “This is no Ashton Kutcher skit, this is some guy who is disgracing the military by wearing a uniform and decorations that are obviously fraudulent.” Someone else Photoshopped the image to mimic an old-fashioned “Wanted” poster, with thick bold letters declaring “WANTED FOR STOLEN VALOR.”

These critics had every right to be upset. It’s taboo to imitate a military officer; it’s also illegal to do so. The Stolen Valor Act, passed by Congress in 2006 and revised in 2013, criminalizes falsely wearing these decorations for personal gain or benefit. Not only do imposters stand to profit from this kind of deceit, which can be construed as an egregious type of theft, but supporters of this legislation also maintain that this kind of fraud diminishes the significance of military insignia. The man wasn’t just breaking the law—he was devaluing the very honor that thousands of active military and veterans fought hard to establish.

A month later, on January 19, 2010, the photographer brought the photos to Christopher Petrowski, an FBI agent assigned to the Houston Division Violent Crime Task Force. Through a driver’s license and database search, Petrowski identified the man as Michael Patrick McManus, a Houston resident who’d had previous brushes with federal law enforcement. Petrowski called McManus and left a voicemail. Two days later, Petrowski received a call from McManus’s lawyer. Petrowski said he needed to interview McManus and obtain the uniform and insignia for evidence. The lawyer replied that his client had fearfully destroyed everything when he realized he’d become “the subject of angry bloggers.”

The U.S. attorney for the Southern District of Texas filed a five-count indictment against McManus in mid-February, charging him with unauthorized possession and deceptive wearing of U.S. and foreign uniforms and medals. According to the criminal complaint filed against McManus, it was a textbook case of stolen valor.

McManus certainly appeared guilty. His election night ensemble was absurd, a haphazard assortment of medals and awards. When confronted, he hired a lawyer and destroyed the evidence. Yet Petrowski and the bloggers didn’t know what McManus felt he had to gain by his actions—and what he had already lost.

Texas has an unusually large number of stolen valor cases. Given that the state is home to 220 military sites and dozens of veteran foundations and associations, Texas is ripe pickings for those looking to profit off of those resources. Josh Kinser, the former field activities director for the Military Warriors Support Foundation in San Antonio, experienced this firsthand during his tenure. Part of the group’s mission is to help struggling veterans apply for home mortgages. After discovering several men had lied about their records, the organization began requiring the submission of a DD 214, the form every veteran receives upon discharge as proof of service. Soon that wasn’t even enough. Doctored forms flooded in. Eventually, MWSF hired two full-time staffers to vet every applicant. “It got to the point where it was just so frustrating. It takes up your time,” Kinser says. “Gosh, I get mad just thinking about it.”

Money motivates some to lie. For others, it’s about the glory of being associated with the military. Many politicians and public figures build careers around their service. Veterans can sometimes parlay distinguished records into civilian success. And while embellished war stories shared casually during a round of drinks are frowned upon but certainly come with the territory, these exaggerations acquire a sinister edge when used to curry public favor. Consider beloved NBC anchor Brian Williams, who was suspended and demoted after admitting he’d falsely claimed to be on a helicopter brought down by rocket-propelled grenade fire while reporting in Iraq in 2003 (he’d actually been in another aircraft a half hour behind). Or take Hillary Clinton: back in 2008, the Democratic presidential candidate said she “misspoke” when she described running from sniper fire during a 1996 visit to Bosnia. (Ironically, Williams himself shredded Clinton’s story in a March 2008 newscast.)

In an age where service is no longer mandatory, joining the armed forces is considered the utmost demonstration of patriotism. Wounded veterans are frequently honored at sporting events and on the news. High-profile organizations like the Wounded Warrior Project attach the label of warrior to veterans. And the rise of the military memoir—like the work of two Texans, Chris Kyle’s American Sniper and Marcus Luttrell’s Lone Survivor—further fuels this hero-worship.

While Luttrell’s harrowing account of an anti-Taliban mission gone awry brought him fame—a bestselling book, a biopic starring Mark Walberg—it also brought him vulnerability. Daniel Lee Marshall was exposed in 2010 for pretending to be an Army Ranger to get close to the Luttrells. “It’s just incredibly weird how strange these guys are to do that and try and infiltrate that family,” says Don Shipley, who exposes “phony Navy SEALs” from his home in Chesapeake, Virginia.

B.G. Burkett knows that behavior all too well. The 72-year-old former first lieutenant has spent much of his life exposing military frauds from his home outside Dallas, investigating about 3,500 cases over the past three decades and penning the 1998 tome Stolen Valor: How the Vietnam Generation Was Robbed of its Heroes and its History with Glenna Whitley. “Why the deceivers lie probably emerges from deep feelings of inadequacy, the need to be seen as a man’s man, bigger than life,” they write. “For some, belonging to a group defined as ‘warriors’ is irresistible.”

Many mainstream military accounts—the ones that are romanticized and mythologized—tend to focus on the more grisly aspects of service, stories of narrow escapes, bloody battles, and other acts of significant derring-do. This propagates an image of all veterans as war heroes when, in fact, most members aren’t stationed “on the front lines.” For those who are, bragging about their accomplishments seems anathema to why they chose to serve at all. “We don’t like the reaction that people give us when they find out we’re SEALs,” Shipley says. “We don’t really like the attention.” But stolen valor offenders seek out that validation and find it a desirable identity to adopt. “They worship those guys. They want to emulate them, certainly,” Shipley notes.

This feigned authority extends beyond the military; fake lawyers and doctors also fall under the umbrella of “impostors,” says Deirdre Barrett, a Harvard University assistant professor of psychology. “Sometimes it’s the most sort of high authority position that they seem to be aiming at, and others seem to want something that would get you an awful lot of sympathy.” Engrossed in the imagery of the false history they create, and buoyed by the attention they receive, many become repeat offenders, Barrett says. When caught, they often reinvent their persona in a new setting.

Jay Rorty, who briefly represented McManus as a public defender in 2004, has had three clients who have impersonated authority figures. “How much in that moment does a person know that they are impersonating?” he said. “And how much are they so much living the role that they believe that it is the case, that it’s all just a misunderstanding when people catch them?”

Michael McManus always wanted to be a hero.

Born in Terre Haute, Indiana, on January 14, 1966, to two unmarried college students, he was adopted at five days old by Michael L. McManus, a Ph.D. student at Purdue University, and his wife. The family soon moved to Connecticut, where McManus’s father took a job with the USDA Forest Service and they adopted another boy, Brian. In 1975, after fifteen years of marriage, the couple went through a contentious divorce, with McManus Sr. eventually gaining custody of both boys, their mother seeing them only occasionally afterward. When he was eleven, McManus and his brother were slow to accept his father’s new wife, a woman who had her own four-year-old son, Nick.

As a child, McManus was unathletic, stubborn and, mischievous, frequently getting into trouble at school. He often lied to his parents; admitting fault was “beyond his capabilities,” his father says. The family spent more than a year in therapy trying to resolve their issues. In high school, McManus earned good grades but participated in few social activities. One day after graduation, he came home from his job at a local supermarket and told his family he wanted to join the Army. His parents were shocked—he hadn’t previously expressed interest in serving—but they tried to be encouraging and supportive.

McManus trained in Alabama, testing well during the aptitude evaluation. To his father’s dismay, he joined the Military Police Corps instead of pursuing a field that could advance his post-Army career, such as engineering. His father remembers his son’s excitement when he briefly returned home after basic training. Every morning, he would jog in camouflage pants and boots.

McManus entered active duty on November 11, 1984. During his three years of service, he achieved the rank of Private First Class, serving overseas in Kaiserslautern, Germany, as a military policeman. He earned expert marksmanship with the rifle and pistol. He told his family he was assigned to Colin Powell’s security detail.

But McManus’s relationship to the military was always uneasy. When he was in boot camp, he would occasionally disagree with his drill sergeant. He was disciplined six times for leaving his post or ignoring directives. A disciplinary form from April 1986 shows that he was admonished for twice sleeping at a sentinel post, earning him a pay level reduction, two weeks of restricted facilities access, and 14 extra days of duty.

Most substantively, McManus was hiding something. On March 31, 1987, McManus was discharged under honorable conditions, denoting satisfactory, but not perfect, completion of duties. On a personnel identification form in his military records, “NOT RECOMMENDED FOR FURTHER SERVICE” was written neatly in all caps.

That day, everything changed.

Years later, McManus told friends and family his military service had ended because of a deeply personal secret, something outside his control: he was gay. The disclosure to a superior, 24 years before the repeal of Don’t Ask Don’t Tell, altered the course of McManus’s life, says James Fallon, his Houston attorney. Had he stayed quiet, Fallon says, he might have remained in the Army much longer. Had he served two decades later, he might have served out the remaining five years of his eight-year obligation. Perhaps he would have made working in the Army’s law enforcement division a lifelong career or transitioned to the private security sector.

That day McManus lost a job—but also a large part of his identity, too. “He loved the military, and so from that time on he had involved himself in different kinds of endeavors that were on the fringe of military meaning,” Fallon says. “That was definitely a big thing with him, to have a chance to go forward to be a hero, just like any other person would want to be.”

Much of McManus’s life after the Army remained shrouded in mystery to his family. After his discharge in 1987, he distanced himself from immediate relatives, only occasionally coming home for holidays.

He came out only to his father—and even that was an accident. After noticing his son coming home in ostentatious attire, McManus Sr. looked through his son’s briefcase, unearthing photos of him at a gay party. When his father confronted him, McManus sent him pamphlets about coming out, and the two slowly began a dialogue.

Back in the civilian world, McManus struggled with the direction of his life. He worked odd jobs, tried for years to graduate from college, and often borrowed money from friends.

He tried to recreate his military experience, collecting medals, uniforms, and insignia from ads in surplus magazines and stores. While living with a friend in North Carolina, he told his father he’d landed an interview for a security officer position in Germany. Afterward he called back in tears, explaining that he admitted he was gay during a lie detector test, at which point the interview ended. Today, such an incident would cause national outrage; three decades ago, this employment discrimination was much more prevalent.

The next time McManus Sr. saw his son, McManus had been admitted to a North Carolina hospital for severe depression. After his release, he lived with his grandparents in a small Indiana farm town. In August 1988, he enrolled at Purdue, his father’s alma mater, studying French and becoming a member of the school’s Delta Lambda Phi chapter, but never graduating. After visiting San Jose State University, in 1993 McManus decided to transfer there and study Chinese instead. There he met Thubten Comerford, a roommate who would become one of his closest friends over the next two decades.

“It was surprising how much we had in common,” Comerford says. Both were adopted, both were gay, and both had served in the military (Comerford in the Navy). “We seemed suited for each other.” Early on, McManus feigned still being on active duty, saying he was on leave to finish college, though he had been discharged six years earlier. He told Comerford he was a captain serving on the Army Reserves’ Special Operations Command, a unit formed in 1987 to conduct missions assigned by the Pentagon and president. McManus showed Comerford his captain’s uniform and a Purple Heart medal, both of which he wore to the 1993 LGBT March on Washington. “I had no reason to not believe him,” Comerford says.

As the two grew closer, McManus frequently spoke about working as a translator and bodyguard for Powell, who in 1986 took over command of the Army’s Fifth Corps in Frankfurt. As part of a “fairly robust personal vendetta,” Comerford says he would castigate Powell for his stance against openly gay men in the military. In a June 1993 press release by GLAAD’s San Francisco chapter, McManus is identified as “Captain McManus” and claims he disclosed his sexuality to Powell, who allegedly replied, “What do you want me to do about it? As long as you are doing your job well, that does not matter to me.” The release states McManus held “top secret security clearance” and quotes him as saying, “It is time for people to realize that sexual orientation is a fundamental part of a person’s identity, just as much as being Asian—or African-American.”

The claims about Powell, absent from McManus’s military records, called his discharge story into question, even though Fallon, his Houston attorney, was prepared to use it as part of his defense. Powell’s chief of staff said while he had many bodyguards during that assignment, he does not specifically remember McManus. Comerford once thought both their military careers were stopped short due to their sexuality, but looking back now, cynicism colors his view of his friend. Comerford told me he believes Michael’s discharge stemmed from dereliction of duty, indicated by his numerous disciplinary infractions.

Despite McManus’s relentless efforts to stay connected to the Army, not everything in his life revolved around it. By the time he moved to San Jose, California, he was already passionate about Buddhism, and he encouraged Comerford to take up the religion in 1994. Two years later, the pair traveled to a Buddhist mountain retreat in Dharamsala, India. They spent six months there, with McManus being recognized as a reincarnate lama—a Tibetan monk in a previous life—in February 1997. In one photo, McManus wears red and yellow robes, smiling with clasped hands as the Dalai Lama passes by. Photos from the trip serve as the centerpiece of McManus’s Facebook, where he went by the name Tenzin Chopak. “That was something that was real,” Comerford says. “There are people that don’t believe that it actually happened because he lied about everything else.” Both men took monastic vows before leaving India in March 1997.

Projecting affluence, and the legitimacy that came with it, was also important. For a while McManus worked at a San Jose café and occasionally held down other jobs, but he struggled to support himself financially (Comerford estimates over the course of their friendship, McManus collectively borrowed approximately $25,000 from him). Yet somehow, McManus always had expensive things. He brought Louis Vuitton luggage for the India trip, and he owned many designer clothes. “I don’t think it was the material things themselves,” Comerford said. “He had a desire to be seen as someone who had those things.”

Shortly after that trip McManus moved to Palo Alto, and his financial struggles followed him. In November 1998, a check bounced when he tried to buy a computer, and less than two years later he was charged with online fraud while purchasing personal items. Both cases were heard on the same day in September 2000, and Michael served a six-month concurrent sentence in the county jail.

Around the same time, McManus told friends he secured a job on campus at Stanford University, where he met his partner of over a decade, a petroleum engineering Ph.D. student, who he moved in with in the early 2000s. McManus would later say he was also in the Ph.D. program there and frequently wore the university’s sweatshirts, though he never enrolled.

While living in Palo Alto, McManus injured his back moving furniture. Several surgeries later, he was in constant pain and had a pump inserted into his side for direct medication application. This led to a painkiller addiction that kept him in and out of drug treatment programs the next several years.

Then, at Louis Armstrong New Orleans International Airport on January 21, 2002, McManus presented a ticketing agent with what appeared to be a military ID. He was scheduled to fly on American Airlines Flight 1970 destined for San Jose, he said, and would be serving as an unarmed air marshal on the flight, thus requiring a seat upgrade to the front row. He’d been upgraded to first class on his trip to New Orleans from California, he said. After checking McManus’s records, the agent told him she couldn’t provide the upgrade, but the gate agent could. As he approached gate C-8, he wore Army fatigues resembling those worn by the National Guard and an ID listing captain as his rank.

The gate agent gave him the access he asked for, and once pre-boarded, he met with the pilot. But the pilot found McManus’s conspicuous attire odd; air marshals should blend in and are usually armed. The sky marshal program, McManus replied, wasn’t up to speed, so it was using Delta Force members “trained to handle any situation.” He examined the galley and bathroom area at the plane’s rear, and he asked the pilot for the “code word” to access the cockpit.

His story unraveled when the flight’s real marshals boarded. The pilot approached McManus, asking if he was a marshal, to which he replied he was a “military version of a sky marshal.” The pilot asked him to de-board.

McManus got on a different flight. The next day, when confronted by San Francisco FBI agents, McManus admitted he’d purchased the ID, uniform, and badges from military magazines and surplus stores. He was flying to California to attend San Francisco’s Fleet Week, an annual celebration where military ships dock at a major city for a week. He told the agents he wore the uniform to receive special treatment by the airline.

On February 1, he was indicted on two felony counts of impersonating a U.S. employee and armed services member to obtain the upgrade. The case was transferred from Louisiana to the Northern District of California, where McManus was living in Mountain View.

(The presiding judge on the case was James Ware, an irony considering that for years, Ware told a story about himself that wasn’t quite his: that his teenage brother, Virgil, had been killed by a racist in Birmingham in 1963, at the peak of the Civil Rights Movement. It was a story he told frequently, especially five years earlier during his nomination for the Ninth Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals in San Francisco, where he’d be the only active black judge. But although the details of the murder and the fact Virgil had a brother named James was true, the story wasn’t. Virgil’s real family members, still living in Birmingham, disputed the judge’s claims in the local newspaper, forcing him to withdraw his nomination.)

In July 2002, McManus pleaded guilty to the second count against him. During his prosecution, his mental health and drug issues came to light. He’d begun counseling during his pretrial release to help him avoid repeating his “needy, yet criminal, behavior.” He received two years’ probation and six months of electronic monitoring, under the conditions that he participate in drug-alcohol and mental health treatment, and “provide his true identity at all times.”

Just two years later, in November 2004, McManus’s probation was revoked for possession of false identification. He requested to be placed in a Texas facility so he could remain close to his partner, who’d recently moved to Houston for a new job. On January 3, 2005, McManus had to surrender for a three-month sentence in a Houston-area prison.

Adam Braun, the prosecutor, suspected McManus’s actions were linked to his self-esteem. “He just kind of seemed like a sad, troubled person that maybe didn’t have a lot to feel special about,” he says. “Maybe that military experience was the highlight of his life, or during that time he felt respected at some subconscious, psychological level to serve that need.”

Against the backdrop of two active wars, in December 2006 George W. Bush signed the Stolen Valor Act into law. It detailed fraud as not only wearing unauthorized medals but also attempting to purchase, sell, mail, produce, or exchange military distinctions for anything of value. False claims became punishable by a $10,000 fine and up to a year in prison. Within the first eighteen months, at least twenty men were prosecuted.

One of those men was Xavier Alvarez, a member of the Three Valleys Municipal Water District Board in Pomona, California. Alvarez claimed to be an engineer, a Detroit Red Wings player, the boyfriend of a Mexican celebrity. One day, he took things too far. At a July 2007 meeting, he introduced himself as a 25-year Marine veteran and a Congressional Medal of Honor recipient. “I got wounded many times by the same guy,” he said. “I’m still around.” The comments of Alvarez, who never served, quickly drew local ire. Alvarez, one of the first to be prosecuted, hired a lawyer to defend his right to free—not necessarily truthful—speech.

Then-Texas Attorney General Greg Abbott led the filing of a December 2011 brief with 19 other states defending the law’s legitimacy and affirming states’ right to police “knowingly false statements of fact.” “When military impostors proliferate unchecked, they diminish the value of military honors by blurring their signaling function,” it read. “This blurring effect causes substantial harm to the military and to the recipients of military honors.” (Four years later, as governor, Abbott has continued supporting stolen valor prosecutions. In May 2015, he signed legislation that made sentencing for those “presenting false or fictitious military record” more severe. “Too many brave American men and women have put their lives on the line for our country to have their records tarnished by someone making a false claim,” Abbott said in a statement.)

But as Alvarez’s case advanced to the Supreme Court, it became clear that simply harming the military’s reputation wouldn’t be enough. In June 2012, the high court struck down the law in a 6-3 decision, citing First Amendment concerns. Although the justices recognized the law’s justification, they disputed the government’s ability to regulate false statements: “The facts of this case indicate that the dynamics of free speech, of counterspeech, of refutation, can overcome the lie.”

The court reached “the entirely right result,” says Rorty, McManus’s one-time public defender. “To rise to the level of criminal activity, there has to have been an intention to gain a tangible benefit. A false claim standing on its own which harmed no one, can result in no benefit to the actor, shouldn’t be criminalized.” Those tangible benefits, like gaining money or property, were written into the revised version of the law, signed by President Obama in June 2013.

The Ninth Circuit appeal phase of the Alvarez case advanced in tandem with the Houston case against McManus for his attire at the 2009 election party. In 2011, McManus’s case was in pretrial phase. Fallon and a team of Yale law students were crafting his defense. Like many in the LGBT community, they argued, McManus had been deeply affected by Parker’s victory. He’d attended the party in his outfit to symbolically express himself and “celebrate the LGBT community’s progress.” In his motion to dismiss, Fallon wrote, “Mr. McManus wore an army uniform and medals to the mayor’s victory party in order to protest both his discharge from the Army and the continuing exclusion of LGBT Americans from the military under Don’t Ask Don’t Tell. Mr. McManus’ possessing and wearing of a military uniform and medals were a form of political expression.” The Alvarez decision the next year would prove them right.

However, McManus continued struggling with drug abuse. His partner, unable to accept his addiction any longer, had moved to New Orleans. After his arrest, McManus briefly stayed with Comerford in Portland, Oregon, where he was supposed to enter a drug treatment program. But Comerford learned of the air marshal incident and realized much of what his friend had told him over the years was untrue. Records requests revealed McManus never actually graduated from Purdue. Or from San Jose State.

As McManus’s stories unraveled, Comerford’s overwhelming emotion was sadness. He knew his best friend had a big heart but suspected dwindling self-worth provided fodder for all the lies. “To have such low self-esteem, to need to invent reasons for people to like you and reasons to fit in was just very sad to me,” he says. “That he did not trust in his own value as an ordinary person and that he had to invent all these things to be accepted or believed in. The thing is, once you start going down that road, it’s even a bigger challenge to come clean about it.”

Houston was sweltering on August 11, 2011, recording a high of 102 degrees and up to 85 percent humidity. After walking into a Subway in southwest Houston, McManus collapsed. He was transported to St. Luke’s Episcopal Hospital, where, in a coma, he was placed on life support. Doctors told McManus Sr. that his son had been taking a cocktail of drugs—Percocet, Ambien, Celexa, Klonopin, Trazodone, and Zyprexa—treating pain, depression, anxiety, and other mental health issues.

A week after his collapse, his family took him off life support. He was 45 years old. An autopsy determined he died from heart disease complications; his major coronary vessels were narrowed 50 percent. The report also noted his chronic prescription medication abuse as likely contributing to his death.

It wasn’t until after McManus’s death that his family and friends, grief-stricken, learned the truth: much of what they knew about him was untrue. Working for Colin Powell. Reaching the rank of captain. Attending Stanford. Possibly even being discharged from the Army because he was gay. Four years later, when McManus would have turned 49, his friends and family remain deeply hurt.

When Comerford learned his friend had died, he felt grief, but also relief. “My reaction was, ‘Thank God for Michael that his struggle was over.’ He was not happy. He was not at peace. It was just constantly struggling and becoming less and less capable of keeping all of those stories straight.”