This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

What was the old world coming to?, I asked Tom Landry. Landry was at his desk, his back to an autographed picture of Billy Graham, facing the big, silver Super Bowl VI trophy, impassive as a museum director, fielding questions with technical, theological, thermo-regular certainty, impervious to the demons that my senses told me were present in staggering numbers.

I mean where is it leading us? This obsession with being first, being best, being No. 1. Tampered transcripts at Ball High in Galveston, rigged Soap Box Derbies in Akron, highly-subsidized 11-year-old Chinamen making a shambles of the Little League World Series, bribes, kickbacks, burglary, perjury, Watergate. Had the monster of our pioneering escaped in the rose garden? It seemed to me that this preoccupation with being No. 1 was rushing us toward the Temple of False Idols, and from there to the paranoiac’s ward.

“I don’t mean football or even sports in particular,” I said, “I’m talking about this country, across the board. This thing, this passion . . . this belief that in the search for success the means justify the end . . .”

Yeah, Landry knew what I meant. He had been challenged before, and I had heard him expound his beliefs many times—in interviews, press conferences, damp locker rooms, and Fellowship of Christian Athletes banquets. “Take away winning,” he had said, “and you take away everything that is strong about America.” But I wanted to hear him say it again.

“You’re talking now about the negative side of winning,” he began, and I fancied that there was a hitch in the toneless economy of his voice. “Generally, achieving goals . . . which in many cases means winning . . . is really the ultimate in this life we live in. Being the best at whatever talent you have, that’s what stimulates life. I don’t mean cheating or doing things that are bad. That’s the negative side. But here’s the thing: what are the alternatives? If you don’t believe in winning, you don’t believe in free enterprise, capitalism, our way of life. If you eliminate our way of life, the American way of life, what is the effect . . . what are the alternatives?”

I said that I couldn’t name them all, but humility was probably one. Peace. Joy. Freedom from the stigma of failure. If this country had the same appetite for peace and brotherly love as it had for war and puritanical vengeance . . . if free enterprise was more than a code word for greed . . . we might become the beacon of the world that we imagine ourselves to be.

Tom smiled his ice age smile: I had known him for 14 years and we had had this discussion many times. Tom did not see a contradiction between the terms pride and humility, any more than some politicians and military men see a rift in slogans like Bombs for Peace.

“Achievement builds character,” he told me. “People striving, being knocked down and coming back . . . this is what builds character in a man. The Bible talks about it at length in Paul, in Romans. Paul says that adversity brings on endurance, endurance brings on character, and character brings on hope.”

“Then hope . . . not joy, peace or love . . . hope is the ultimate goal?”

“That’s right,” he said. “Character is the ability of a person to see a positive end of things. This is the hope that a man of character has. It’s an old cliché in football that losing seasons build character, but there is a great truth in it. I’ve seen very little character in players who have never had to face adversity. This is part of the problem we see in this country today . . . young people who have never really had to struggle in life, when they do eventually face problems where they need to turn to character, it’s not there. They turn to the alternatives: drugs, alcohol or something.”

Drugs, alcohol or something. Hmmm. I wondered what that something could be. Al Ward, the Cowboys’ assistant general manager who had known Landry since 1945, recalled that Landry’s own life was a progression of goals . . . to make his team at Mission, Texas High School, to make it at the University of Texas, to make it with the New York Giants. “But each time he reached his goal,” Ward said, “the kick wasn’t there. Then he found religion. Now he is satisfied with life.” Though he had been a Methodist since boyhood, Landry claims he didn’t become a Christian until 1958, two years before he became the Cowboys’ first and only head coach. “I was invited to join a Bible-study breakfast group at the Melrose Hotel in Dallas, and I realized I had never really accepted Christ into my heart. Now I have turned my will over to Jesus Christ,” he explained. There is nothing unusual in getting off on Jesus, or even using Holy Scripture to justify any act or event, but in coming to grips with the alternatives—that is, eliminating them—Landry seemed to have refined the narcotic qualities of Paul’s definition of character.

Landry was relaxed, more than I had ever seen him, strangely relaxed considering that it was less than three hours before game time, perversely relaxed for a man who detests small talk and was now being bombarded with it: 30 minutes, my alloted time, had elapsed and I hadn’t yet mentioned football to the man who is supposed to be the finest brain in the business. Landry’s cobalt eyes studied me, waiting for a question, and I tried to remember what had happened in the year since I saw him last. He appeared warmer, less regimented, even vulnerable. Why?

Well, two things were obvious. The Cowboys had not repeated as Super Bowl champions, thus laying waste all that talk about a Cowboy dynasty. And 15 of the 40 players who did win the Super Bowl had been traded or forced into early retirement. Unlike previous champions—the Giants, the Packers, the Colts—the Cowboys weren’t waiting for the skids, they were rebuilding while they were still near the top.

But there was something else, something Cowboys president Tex Schramm mentioned earlier. We were talking about the criticism that Landry treats his players like so many cards in a computer file.

Schramm said: “You have to remember, Tom is a very honest, straightforward person. He is not a con artist. He treats his players like adults. Some coaches sell their players a bill of goods . . . you’ve seen it, they stop just short of holding hands when they cross the street . . . and these coaches get away with it because their consciences don’t bother them. Tom can’t do that.

“I think one thing that happened last year was that Tom tried to adapt . . . he tried to have a double standard. Even though it was against his nature. This year there is one standard and everyone conforms. Tom has gone back to his original concept of gathering about him the type of players he likes.”

It is staggering, the roster of non-conformers who had gone down the drain. Duane Thomas, Tody Smith, Billy Parks, Ron Sellers, Dave Manders, and in years goneby talents like Don Meredith, John Wilbur, Lance Rentzel, and Pete Gent, to name very few. Landry lifted his eyes and they vanished. Thomas was a landmark in Landry’s experiment with the double standard. Thomas got away with things that in Meredith’s times would have called for thumb screws. There were those in the Dallas organization (players, especially) who resented Thomas leading them to two consecutive Super Bowls almost as much as they resented not getting there without him last season. The official theory is, the Cowboys paid last year for the sin of putting up with Thomas in two previous campaigns.

Take the case of Billy Parks, heretofore a good white boy with a sterling reputation as a pass receiver. In the aftermath of Duane Thomas, Parks insisted on wearing white football shoes and speaking out against the war. Once, he refused to play because his black friend Tody Smith was hurt, and another time he took himself out of a game because his presence on the field was keeping a black receiver on the bench.

Now they were gone, the non-conformers as well as the non-achievers, and Landry looked more relaxed than I’d ever seen him. You know the illegal smile, the one John Prine sings about? Landry wore what you might call a legal smile.

He told me: “I’ve come to the conclusion that players want to be treated alike. They may talk about individualism, but I believe they want a single standard. Yes, that belief is behind many of the trades we made. If a player is contributing and performing the way he ought to, he will usually conform. Now if he isn’t performing well and not conforming to team standards either, he ought not be around. We can put up with someone who is getting the job done as long as he’ll conform. But we just can’t get along with a player who doesn’t conform or perform. No way.”

There is a common misunderstanding among football experts that the best team—the team with the most talent—wins. It is true that you don’t win without talent, but in the National Football League there are five or six teams of more or less equal ability. In those delirious hours after Super Bowl VI when the Cowboys were drunk with victory and talk of the new dynasty rained down, Landry permitted himself a Virginia reel around the dressing room, then he struck a note of caution. The question, Landry said, is will the Cowboys perform at the same level next year.

“At the championship level,” he said, “there is a very narrow edge between winning and losing. You don’t have to take much away from a team to keep them out of the Super Bowl. The hunger that makes a player work hard enough to win is inherent in some, but in others it has to be built in. The edge comes from trying to achieve a goal. Once you’ve achieved it, it is very difficult to look back at the price you’ve paid and then make yourself do it again.”

At the bottom of the sweet cup of Super Bowl VI, Landry read the future. Though they were essentially the same team that won the Super Bowl, the 1972 Cowboys were found lacking. There is only one Super Bowl; and it’s no disgrace not to get there: in recent years, only Vince Lombardi’s Green Bay Packers have been able to repeat as champions.

That is what hurt, the fact that Lombardi had done it. There had been no double standard at Green Bay. All-pro guard Jerry Kramer once remarked, “Coach Lombardi treats us all the same—like dogs.” Even before his death a few years ago Lombardi was a football legend, a vane, volatile, uncompromising dictator, a living metaphor for Number 1. Could Tom Landry afford to be something less? Not if he had character.

It wasn’t Jesus or Paul that Tom Landry had in mind when he did corrective surgery on the 1973 Cowboy team, it was Vince Lombardi.

Lombardi and Landry were guiding forces behind the great New York Giants’ teams of the Fifties, and when pro football climbed out of the coal yards into the affluent livingrooms of America in the early Sixties, they were major influences. Jim Lee Howell was the head coach of the Giants, but it was Lombardi’s offense and Landry’s defense that gave the Giants character. After Lombardi moved on to the head job at Green Bay and Landry took on the new franchise in Dallas, Howell resigned, explaining that “Ten victories don’t make up for two defeats.”

“Lombardi was a much warmer person than Landry,” says Wellington Mara, the Giants’ owner. “He went from warm to red hot. You could hear him laughing or shouting for five blocks. You couldn’t hear Landry from the next chair. Lombardi was more of a teacher. It was as though Landry lectured the top 40 per cent of the class and Lombardi taught the lower ten per cent.”

Landry was still a player-coach when he designed the modern 4-3 Defense, pro football’s equivalent of the doomsday machine. Later, at Dallas, Landry pioneered a method of combating that defense—the multiple offense.

“Landry was a born student of the game,” says Em Tunnell, the great defensive back who played with (and later for) Landry. “But he was kind of weird. After a game the rest of us would go out for a beer, Tom would disappear. He was always with his family. You never knew what was going through his mind. He never said nothing, but he always knew what was going on. We didn’t have words like keying (ie: reacting to prearranged schemes) in those days, so Tom made up his own keys and taught them to the rest of us.”

By training, Landry was an industrial engineer: he had a need to know what was going on. “I couldn’t be satisfied trusting my instincts the way Tunnel did,” Landry explained. “I didn’t have the speed or the quickness. I had to train myself and everyone around me to key various opponents and recognize tendencies.”

“Most of us just played the game,” Frank Gifford recalls. “Landry studied it. He was cool and calculating. Emotion had no place in his makeup.”

Another former Giant, Dick Nolan, who went on to become head coach of the San Francisco 49ers, says, “I remember one time Tom was at the blackboard, showing me that if their flanker came out on the strong side on a third-down play, and the fullback flared to the weakside, I was to follow the fullback out a few steps and then race back quickly because they would be bringing the wingback inside me to take a pass. ‘But Tom,’ I said, ‘what if I commit myself that completely and the wingback isn’t there?’ Tom just looked at me without any change of expression and said, ‘He will be’.”

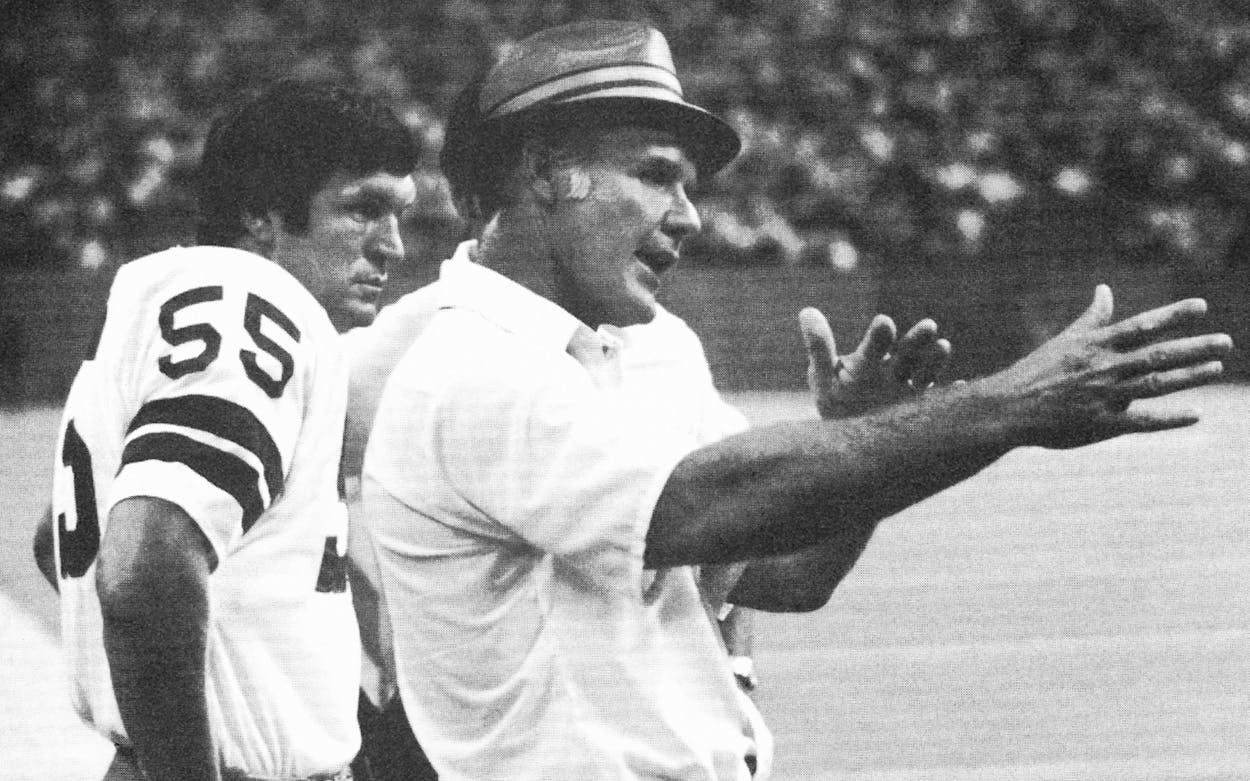

Landry’s reputation was constantly exposed to ridicule in the mid-1960s, not only because his Cowboys twice lost championship games to Lombardi’s Packers, but because Landry himself came across as such a cerebral paradox, a rigid, humorless figure stalking the sidelines of the Cotton Bowl in his felt snapbrim and buria1-policy dark suit. Like the team he coached, Lombardi was purely physical, seething, kicking, pushing, openly humiliating those around him; and getting results. If the Packers were the bludgeons of pro football, the Cowboys were the slide rules. Paul Hornung once observed, “Lombardi would be kicking you in the rump one minute and putting his arm around you the next.”

Landry would react to a great play or a poor play in the same dispassionate manner, as though it were ancient history. When a player was down writhing in agony, the contrast was most apparent: Lombardi would be racing like an Italian fishwife, cursing and imploring the gods to get the lad back on his feet for at least one more play; Landry would be giving instructions to the unfortunate player’s substitute.

Landry once explained: “The reason I take on the appearance of being unemotional is I don’t believe you can be emotional and concentrate the way you must to be effective. When I see a great play from the sidelines, I can’t cheer it. I’m a couple of plays ahead, thinking.

“Lombardi’s style of play was very different from ours. The Green Bay system of offense—we call it the basic system—was that you were going to run the power sweep regardless of what the other team put up against you. Run that play over and over until you could execute it in your sleep. It was all execution. So Lombardi had to develop the players to an emotional pitch, keep them doing their best all the time against a defense that knew what was coming. The Packers had to stay very high emotionally to win.

“Our system is different. We run a multiple offense and must take advantage of situations as they present themselves. Everything we do from every formation doesn’t work against every defense, so we have to concentrate, we have to think. Our defense is also quite complicated. It depends on reading movements and formations and knowing where to go. Therefore the nature of response from the sidelines must be very different. The players don’t want to see me rushing around and screaming. They want to believe I know what I’m doing.”

Lee Roy Jordan, Dallas’ middlelinebacker, explains: “Landry isn’t a praising coach, he’s a corrective coach. If you do something right, that’s what you oughta do. He only talks when you do something wrong. If Tom says ‘damn it’, you know something severe has happened.”

There were traces of empathy when the Packers referred to Vince Lombardi as Il Duce. Landry has been called Old Computer Face, a description that has all but vanished with the non-conformers and non-achievers. Pete Gent used to say he could tell when Landry was mad, the muscles beneath Landry’s ears would pop out and his eyes would sort of glaze. “His normal method of discipline is to treat you like a number,” Gent said. “He seems to be concentrating on talking to you mainly to keep you from vanishing.”

Gent, author of the bitterly-critical pro football novel North Dallas Forty [read: Dallas Cowboys], agrees with another ex-Cowboy, Duane Thomas: “Landry is a plastic man. And yet, there is this paradox—in Landry’s presence you do not feel the cool platitudes of plastic and computers, you feel something more visceral. You feel fear.” Meredith and other ex-Cowboys have said the same thing. It is the fear that no matter how hard you try or how much you care you will be found inadequate.

Landry hadn’t read Gent’s novel and didn’t plan to, but he was aware of the general criticism: bigtime football is dehumanizing, brutal and unfairly stacked on the side of management.

In rebuttal Landry said: “It’s an amazing thing, this whole area of criticism . . . the one thing a player respects in a coach is that the coach makes him do what he doesn’t want to do in order to win. Lombardi had great respect from his players, not because they liked him personally but because he made winners of them. That is what all coaches are attempting to do, make players do things they don’t want to do in order to achieve success. The people who usually level this sort of criticism [read: Gent] are the people who didn’t achieve.”

By Landry’s code, you could stick Gent’s ration of character on the back of a postage stamp. Gent was not a great player, but he hung around for five years. Landry never understood why Gent, Meredith and others sat at the rear of team meetings, laughing hysterically. Gent explains why in his novel: they were cracking and passing snappers of amyl nitrate. Gent once observed of Landry’s playbook, “It’s a good book, but everyone gets killed in the end.” Gent’s own book has already earned him more than $500,000. Non-achiever, indeed.

Meredith, the honky-tonk hero, was a special case. From the beginning he was the Cowboys’ future. Coming off a brilliant career as an All-American quarterback at SMU, Meredith approached pro football as though he were Popeye saving Olive Oyl from the cannibals. Meredith’s quality was leadership, an ability to strike a spark of hope in the most hopeless situation. That is why he was called Dandy Don, a name Landry never appreciated. Meredith could rally a team from certain defeat, or splinter the sobriety of a practice session by perking off his helmet and threatening Cornell Green with bodily harm. He played it for laughs: the notion of Meredith threatening a headhunter like Cornell Green was beautifully absurd, and everyone appreciated it—everyone except Landry, who reminded the Cowboys in the meeting that night: “Gentlemen, nothing funny ever happens on a football field.”

I don’t know if Landry ever saw it, but beneath all that tomfoolery and searching Meredith was essentially the person he joked about—a good ol’ East Texas boy, eaten up with talent and the Protestant vision of material success, fairly begging to excel and be recognized. Meredith endured against his own better judgment. He played many games when he could have rightly been in the hospital.

Meredith’s unhappy decision to slide into premature retirement came after Landry supplied an obstacle Meredith wasn’t prepared to endure. Landry pulled Meredith from the 1968 playoff game with Cleveland and replaced him with Craig Morton. Ironically, Landry pulled Meredith for throwing an interception that should have been credited against Landry’s disciplined system of play. According to Landry’s gospel, the Cleveland defensive back who intercepted Meredith’s final pass should have been on the other side of the field. Unfortunately, the Cleveland defensive back was in the wrong place. It wasn’t that Landry was wrong; Cleveland just wasn’t right. Meredith couldn’t endure the consequences—the humiliation that after all these years of enduring he could be benched for non-achievement.

When Meredith went to Landry, his pride crushed and personal problems weighing around him like a 90,000-ton infection, thinking that at last he had made the right choice, a choice that would please Landry, the choice to quit football—then Landry would stay in character and say: straighten up, don’t do it, forget it ever happened and smile tomorrow. Instead, Landry looked at him coolly and said: “Don, I think you are making the right decision.”

Landry contends that he was “treating Don Meredith as an adult,” respecting Meredith’s right and ability to decide for himself. But given their relationship, a relationship Landry controlled, that was no way to treat Don Meredith.

When I was a sportswriter in Dallas Meredith and I had this unspoken arrangement whereby he would tell me what I needed to know and I would change his quotes to make both of us appear literate. Meredith had only one reservation to this arrangement. “Watch out for my image,” he would caution me after every interview. Meredith saw himself as a 13th-century troubadour persecuted for his good intentions. He saw Landry as the Black Monk, a creature who could swallow himself without changing form. If Landry understood the depth of Meredith’s paranoia, he never let on.

Sitting now across the desk from Landry, looking through the man and seeing my own reflection, I wonder: what image does Landry have of himself? I have been in many coaches’ offices and observed that the decor is narcissistic—for example, the walls of Bear Bryant’s office are papered with pictures of the Coach and his Team, the Coach and his Family, the Coach and Phil Harris, the Coach and his Buick. But there are only two pictures in Landry’s office—a small, gold-framed portrait of his family, and the large autographed picture of Billy Graham looking down from infinity. Is it possible that Landry sees himself as a rock?

I ask Landry if he thinks he has changed in the last four years and he takes a long time to answer. “I’ve tried to,” he says. “I think I’ve become more aware of people as individuals. I know the criticism—that I look at my players as numbers—and I guess there’s something to it. People my age . . . we grew up with the Depression, the War . . . a time of ICBMs and pinstripe suits and rampant materialism. But times are changing. I see that and I make an effort to change, too.”

Has Landry changed? I ask Clint Murchison, Jr., the Cowboys owner. “His hair has gotten shorter,” Murchison says. Anything else? “Not that I know of,” Murchison says.

They are subtle, befitting their instigator, but the changes are there. There are fewer rules, veteran players tell me. Veteran players (though not rookies) can wear their hair any way they please, and with a few exceptions like Bob Lilly and Roger Staubach, most of them look like candidates for a drug raid. Landry personally sees to it that the word “optional” is printed on the schedule announcing the time and place of the weekly Sunday devotional. And the double standard, while officially reputed, exists as a practical matter.

“Just before training camp,” Al Ward tells me, “Walt Garrison asked Landry for permission to ride in a rodeo. Landry has strictly forbidden Garrison to rodeo, but of course Garrison does it anyway. But this time, when he asked permission, Landry just said, ‘I don’t want to know about it.’ ”

In the preseason game against Kansas City Landry did something that no one in the press box could remember seeing him do before—he walked over to an injured player and inquired about his health.

What was it that Paul said again . . . . about adversity and endurance and character and hope? Hope for what? More adversity? I look at Tom Landry again and now I know his self image. Landry sees himself as a circle. So be it.