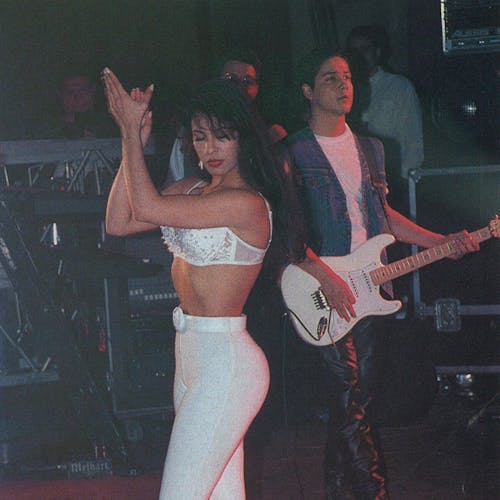

Is tejano dead? That question has been kicked around so often since 1995, when Selena died tragically, one might actually start believing that the music of assimilation has assimilated itself into extinction. And justifiably so. No other tejano artist has come close to achieving her success. Selena Quintanilla Perez was the total package: She was talented, she was smart, she was attractive, and she was a star destined for greater stardom. Even five years after her murder, she’s still the biggest thing in tejano. Sales of her albums remain strong, with two new compilations recently appearing on the Billboard 200 national album charts, a level that no tejano act has reached since her passing. In March the biggest buzz at the Tejano Music Awards in San Antonio was the new musical based on Selena’s life, which was kicking off a Texas tour before heading to Broadway.

There’s no question that had she lived, Selena would be at the forefront of the Latin music explosion that has raised the profiles of Ricky Martin, Marc Anthony, Enrique Iglesias, and Christina Aguilera, a movement in which the absence of any tejano act is glaring. Emilio’s prominence has declined as traditionalists like Bobby Pulido and Michael Salgado have grown more popular; he has also suffered from well-publicized personal problems. La Mafia, which had rivaled Selena in sales, was torn apart by a lawsuit filed by departing co-founder Leonard Gonzales and has only recently gotten back on its feet with a three-record deal with the Los Angeles-based label Fonovisa. Mazz split in two, with singer Joe Lopez forming La Nueva Imagen de Mazz and creative director Jimmy Gonzalez putting together the Original Mazz. But even with Selena’s contemporaries struggling, does that mean tejano is dead?

“If it’s dead, I’m out of a job,” sighs Jonny Ramirez as he picks at his steak at an upscale restaurant near the San Antonio airport. As the morning host of KXTN-FM, Tejano 107.5, Ramirez is literally the voice of the music in the capital city of tejano. Both he and his drive-time partner, J. D. Gonzalez, say that tejano appears to be undergoing an identity crisis, but they wonder whether it’s a reality or a matter of perception. Ramirez acknowledges that KXTN is no longer the city’s top-rated station, as it was during the mid-nineties, but he points out that it is among the three most-listened-to stations in San Antonio, that its audience numbers are higher than ever, and that the cost of a one-minute advertisement on Tejano 107.5 is higher than that at any other frequency in the city. Since the station went on the Internet at the beginning of the year, e-mails from listeners as far away as Guam have poured in.

“We’ve got our own sound,” explains Gonzalez. “Our market is so specific. We’re not a mainstream genre.” Ramirez agrees: “It’s not a sound, per se. It’s a lifestyle. We love rock and roll, blues, jazz, country. We’re hard to pin down.” Ramirez and Gonzalez are typical of the tejano listener: Both are under forty, sophisticated, and bilingual, and they’re both trying to make sense of tejano’s latest trend: a return to the rural ranchera sound that tejano sought to separate itself from when it emerged in the fifties and sixties. It’s all about roots, and it’s turning the business upside down.

Consider Los Palominos, a Grammy-winning group from Uvalde that takes a more traditional, almost rural tact. The band dresses in matching Western duds, sings cowboy-style ballads, and uses the accordion as the lead instrument. Like Intocable and Michael Salgado, it is expanding its fan base not into the English-language general market, as it’s called, but into Monterrey and other areas of Northern Mexico, where tejano and regional Mexican are almost the same. But the crossover stops there. Spanish radio in Los Angeles and Chicago is still influenced by what’s selling in the interior of Mexico, where grupos like Los Tigres del Norte and Bronco rule, not by what’s selling in Northern Mexico and South Texas, which the rest of the music industry still considers the boonies.

Mando Lichtenberger, Jr., the Houston-based producer of La Mafia and Los Palominos, saw the shift coming ten years ago. As the major record labels were locking up all the big tejano acts with overly generous contracts, he found Los Pals playing a rawer kind of tejano, one that was too rootsy for what was being played on the radio but one that would come to influence other musicians, such as singer Michael Salgado. Salgado, a raspy-voiced romancero, emulates the vocal gymnastics of Cornelio Reyna, who played with the great Ramón Ayala, the man who started a retro roots sound long before it was cool. “What’s happening now is, everything that’s being played has a Ramón Ayala sound,” says Lichtenberger. “In that respect, tejano has exploded, but not in the way tejano radio anticipated.” In other words, the regional sound has become more insular, which has forced those acts seeking the Latin mainstream to adjust. La Mafia, for example, hires songwriters from Mexico and Argentina to overcome the regional and cultural differences. It’s a matter of style, Lichtenberger says. “Until our Spanish gets more refined, we’re at a disadvantage when competing against Luis Miguel or Marc Anthony,” he says. “Tejano, the vehicle we once thought would carry us into the mainstream, is more limited now. Selena and La Mafia were able to find that middle ground between appealing to tejano radio in Texas and finding a fan base outside Texas.”

The radio makes the contrast clear. Houston’s leading Spanish-language station, KLTN-FM, Estereo Latino 102.9, is ranked number one in the general market, playing more of a pan-Latin selection of music, similar to what listeners in Chicago or Los Angeles hear. A similar station is making inroads in San Antonio. For tejano radio formats to survive, Lichtenberger believes they need to integrate more Latin artists along the lines of Ricky Martin, Jennifer Lopez, and Enrique Iglesias: “Tejano has felt threatened by these broader formats because they’re getting a bigger and bigger share of the audience. I think if they played them along with classic Selena, Ram [Herrera], Jay Perez, and Mazz, they’d do better.”

But that doesn’t mean that tejano acts can’t cross over into the mainstream. Look no further than Selena’s intimates to understand that. Her brother A. B. Quintanilla has enjoyed considerable success with his Kumbia Kings by rendering cumbias into pop confections. His Amor, Familia y Respeto has sold approximately one million copies, but Quintanilla’s most interesting material are two English-language cuts, “Together” and “U Don’t Love Me,” which are both straight out of the Backstreet Boys’ book of sweet harmonies. Meanwhile, Selena’s husband, Chris Perez, has reached for a broader audience by ditching the tejano sound altogether in favor of rock en español.

Still, the artists aren’t necessarily the ones who are dictating the shift. Consolidation of the music industry, done in the name of marketing and efficiency, has compounded the separation. Given tejano’s localized appeal, the Latin music industry would prefer not having to contemplate the genre at all, which is marked by its many stylistic quirks. “I have this belief that the big labels would rather get rid of the regional sound,” says Lichtenberger. “They’d rather market music they understand instead of hiring middlemen who understand tejano. For every Marc Anthony who sells sixty thousand copies, it’s one more blow to the tejano sound.

“Look who’s appearing at the Tejano Awards Show and see where the priorities are. Five years ago it was [second-generation tejano act] Bobby Pulido. Now all the attention is going to mainstream Latin pop.”

The vacuum created by the majors has been filled by Texas-based independent record labels and mom-and-pop record stores, both of which can respond more quickly to the changing tastes of the tejano audience. That explains the success of new labels such as Luxor, Tejas, and Chipinque and the resurgence of established ones like Freddie and Joey International. Similarly, several old-guard acts are enjoying renewed attention, notably vocalists Ram Herrera, Jay Perez, and Shelly Lares, who has breathed fire into a traditional ballad called “Volver, Volver.” Most eyes and ears though are on Elida Reyna, the leader of Elida y Avante. The 23-year-old Valley girl from Mercedes shares Selena’s natural beauty and exhibits flashes of her vocal power, but even after carrying home four trophies from this year’s Tejano Music Awards, she’s still cultivating a style that will separate her from the pack. There will never be another Selena, but Elida just may have the right stuff to match her firepower and become a star recognized by the rest of the Latin music world. Whether the industry can accommodate her aspirations is the musical question that has yet to be answered.