If the old car had been a horse with a broken leg, he would have shot it. It clanked and clattered as if its guts were falling out onto the highway. He pulled off to the side and cut the ignition. Clay Baldwin knew the symptoms. It had blown a rod. It wasn’t going any farther except under tow. A sign a mile or so back had said it was ten miles to the next town.

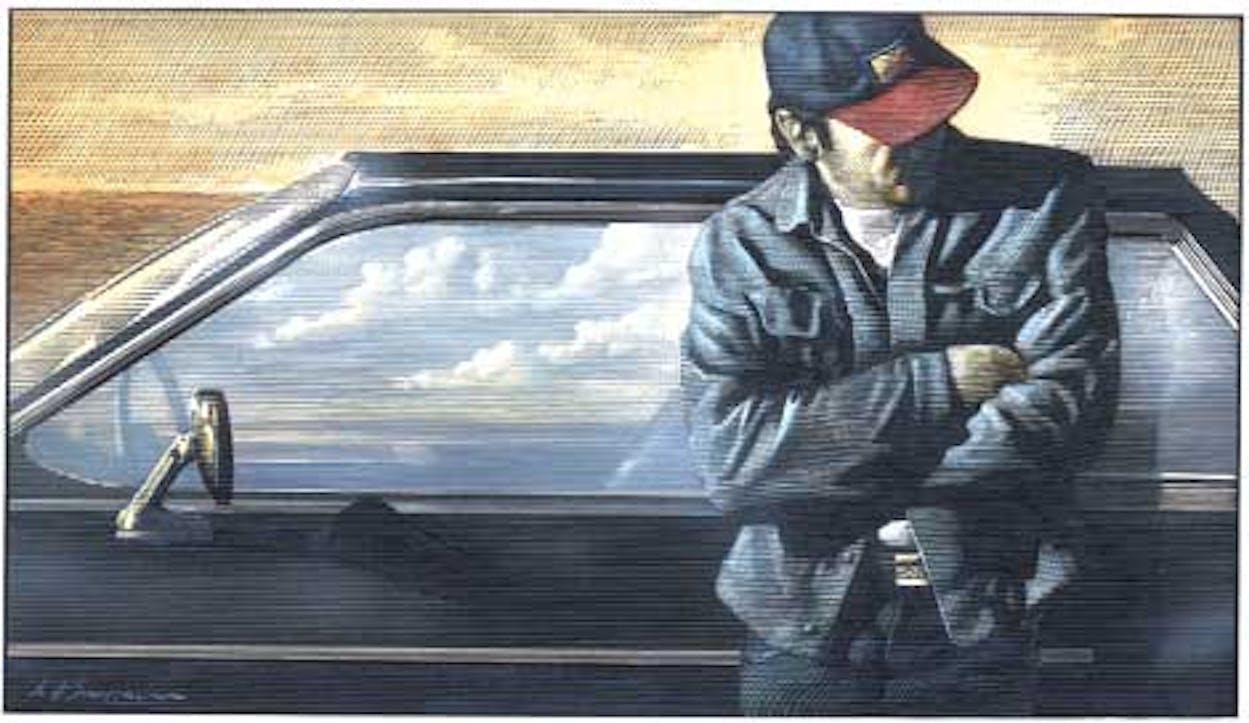

Grumbling to himself, he lifted the hood and looked at the motor, though he knew he could not do a damned thing to fix it. He left the hood up as a signal of distress and sat back down behind the wheel, waiting for some kind soul to stop. He had not encountered much traffic. He resigned himself to a long wait.

Baldwin mentally calculated how much this might cost him and how much was left in his wallet from that oil-patch job at Odessa. After his last alimony payment he still had a few traveler’s checks and a credit card he could float a while to stall his creditors.

A sheriff’s department automobile slowed, made a U-turn in the highway, and drove up behind him. Baldwin thought, Oh, hell!, and wondered what infraction he was guilty of this time. He braced himself. It had long seemed to him that cops were eternally hunting for an excuse to roust a workingman.

Getting out of the car, the officer unfastened the snap that secured his pistol. He had the look of a young rookie trying to cover his insecurities with an exaggerated show of authority. In his Army days, Baldwin had seen the same look in shavetail second lieutenants.

He read the words “deputy sheriff” on the man’s shiny badge. “Trouble?” the deputy asked, though there was no other reason Baldwin would be stopped here with the hood up.

“Rod,” Baldwin said. “They got a garage in the next town?”

“Yes.” The deputy eyed the car suspiciously. “This wreck looks old enough to vote. You sure you’ve got the money to pay for fixin’ it?”

Baldwin took out his wallet and showed a quick flash of green without allowing the officer time to rough-count it.

The deputy nodded. “I’ll give you a lift to town. They’ll send out a tow truck.”

“I’m obliged.” Baldwin locked his car and climbed into the other vehicle. He felt uneasy about sitting so close to a cop, no matter what kind. He had a feeling cops could read a man’s mind and sense not only his past sins but any future ones he might be contemplating. It was a foolish notion, and he chided himself for it. His conscience was clear. Well, not entirely, but time and distance had eased the weight of it.

Driving, the deputy kept glancing sideways at him. He probably did not like the scar on Baldwin’s left cheek. But that had come innocently from a mishap on a rotary rig, not from a fight.

Trying to remember if he’s seen my description, Baldwin thought.

The officer asked, “You got kin around here?”

“No, just prospectin’ for a job.”

“What do you do?”

“About anything. Cowboyed a little, carpentered a little. Mainly I’ve roughnecked in the oil fields.” He started to explain the scar but stubbornly decided, Let him guess.

The officer said, “You won’t find anything around here, I’m afraid. Most of the fields are into water-floodin’. That comes just before the benediction and the burial. As for ranches, they’re runnin’ on the rim too. Nobody’s puttin’ up any new buildings. They’ve got too many vacant ones now.”

“There’s a lot of that goin’ around,” Baldwin said, grimacing. “Jobs ain’t easy to come by.”

“So you’ll be travelin’ on as soon as you’ve got your car fixed?” The deputy sounded hopeful.

“I don’t see much choice.” Baldwin wondered how long the wait would be. Nothing was worse than to be stuck in a strange town without anything to do. “They got any beer joints here?”

“A couple.” The deputy frowned. “My boss is a tough sheriff. Anybody drunk and rowdy gets a quick ride to the jailhouse. His idea of dinner for prisoners is a slice of bologna and a piece of light bread. You wouldn’t like it there.”

It appeared he had already made Baldwin out to be a troublemaker. He wasn’t, ordinarily. He just didn’t let anybody walk over him more than once.

He said, “All I want is to get my car runnin’ and put some more miles on it.”

“Looked to me like it has too many already.”

At the edge of town Baldwin saw a sign: “Twin Wells, A Friendly Place.” Several boarded-up buildings had fading signs that indicated a more prosperous past. Broken-out windows bespoke idle town boys with no recreational facilities to channel their energies. He saw a motel that had once been a Best Western. The sign was painted over with a new message: “Lone Star Motel, American-Owned.”

That assured the finicky that it was not a Patel motel. It meant nothing to Baldwin one way or the other. His only concern was that it not cost too much.

The deputy followed Baldwin into the garage, where a mechanic slid out from under an automobile, wiping his greasy hands on a greasier rag. He gave the deputy an uneasy look, then turned to Baldwin. “Somethin’ I can do for you?”

Baldwin explained about his car. The mechanic said, “Give me the keys. I’ll have Speck run out there with the tow truck.”

“Got any idea what it might cost?”

“Not till I get under the hood. A rod—now, that won’t come cheap. I’ll likely have to order parts. How do you figure to pay?”

“I can pay for it, only keep it down.” He could see that he would need some of those traveler’s checks if he had to stay around here a few days. “Whichaway’s your bank?”

“Corner of the next block. You can’t miss it. It’s the only buildin’ on Main Street that don’t need paint.”

The bank’s rock-solid 1940’s conservative exterior hinted at business suits, white shirts, and ties. Inside, Baldwin saw not even a sports jacket. The generation that had built the bank was not the one that operated it today. He walked up to a pretty young cashier who might have interested him if he had been in a better mood. He showed her the checks he wanted to cash. She asked, “Do you have an account here?”

“No, ma’am.” He started to add “nor anywhere else” but decided against it.

She said, “Then you’ll have to get an okay from Mr. Johnson. He’s in a conference at the moment.”

Baldwin saw two men behind a glass partition, squared off on opposite sides of a desk. A small sign said “Alexander Johnson III.” Angry voices rose over the partition, and the argument appeared ready to break into a fight. The bank employees were painfully obvious in their attempts to pretend they did not hear.

A voice shouted, “Damn you, Alex. You collected enough interest off of me in the good years to pay for that big house you live in. Now you’re cuttin’ me off. You’re fixin’ to break me.”

“You’re breaking yourself, Joe Newby. You’ve refused to adapt to change. Your business has been going down the drain while you keep spending as freely as you ever did. That big discount store is eating your lunch, and you’ve made no changes to help you compete.”

Cursing, Newby charged out of Johnson’s office, his face scarlet. He bumped against Baldwin and growled, “Get out of my way, goddammit.”

Baldwin restrained himself from an urge to strike back. That’s once, he thought.

Friendly place? Like hell!

Next Month

Chapter Two, by Dominic Smith, in which a roast beef sandwich leads Baldwin to a dangerous encounter.