A rucksack, empty as a ghost, dangled from Deputy Dave’s hand. A .357, which he’d pulled from the bag, sat on the table. Baldwin recognized both. He’d retrieved the rucksack from his car before the mechanic hoisted the clunker onto the rack, and he’d unpacked deodorant, his toothbrush, and clean clothes at the motel, but he couldn’t recall the bag after that. As for the revolver, he was sure Belly and Newby were the only ones who’d held it.

He nodded at the .357. “Never touched it.”

“And you haven’t seen Sally?” the sheriff asked. “Or Pop-Tart?”

Baldwin remembered a string of bars and a slow dance with a woman in heels and a vinyl skirt she thought passed for leather—not the classy sort of girl a banker married. But her name was Connie or Corrine. Newby’s son had talked nonsense about Pop-Tarts yesterday morning, but Baldwin hadn’t met anyone by that name.

“Never introduced to either one,” he said.

The sheriff poked a toothpick between his teeth, then pointed it at Baldwin. “We got a man shot dead, Sally’s missing, and I’m staring at an ex-con with a scar that I like for it.”

“A jury will expect proof. Got any?”

“Circumstantial.” The sheriff worried his jaw. At 6 a.m., after a long night of questions, he looked troubled but still clean shaven. “That’s just furniture. Any crackerjack attorney can arrange the room to make you look innocent.”

Baldwin glanced at the rucksack dangling from Deputy Dave’s paw. “So I’m free to go?”

The sheriff opened the door but blocked the passage with his arm. “Maybe my dimwit sister was screwing Joe Newby, but she loved Alex. And no man deserves to die like that.”

Baldwin stared at the sheriff. “Your sister?”

Deputy Dave snorted, offered to beat some brains into Baldwin. “The ‘stupid’ routine’s getting old.”

The sheriff held up his hand. “No one messes with my family,” he said to Baldwin. “Heaven help you, son, if Sally doesn’t show up safe. And soon.”

Baldwin didn’t appreciate any man calling him “son,” particularly one a decade younger than him. Honestly, Baldwin felt phony every time Katherine called their boy his son. A man didn’t earn that privilege if he couldn’t look in the bathroom mirror and see himself a father. Back at the hotel Baldwin tried, and what he saw looking back at him was just someone’s punching bag. He rooted about, hunting for his rucksack, though he knew it wasn’t there. He skipped the shower and sprawled on the bed, still wearing last night’s clothes. When he woke, it was 9 a.m.

Inside the front office of the Lone Star, the cigarette stink choked Baldwin. A bag of Mrs Baird’s and some pastries old as rocks sat on the breakfast bar. The same gritty woman watched TV behind the desk, dragging on her Camels. A housewife, in a T-shirt that said “I heart Drew,” fretted over the cost of Barbasol on The Price Is Right.

The clerk considered Baldwin’s rumpled clothes, his scraggly face. “Guess you’ve no idea how much shave cream costs either.” Her voice sounded like a truck crossing gravel.

“Not today.”

She squinted at him. “Your room is thirty-seven dollars whether you sleep in it or in the clink.”

Baldwin pulled out his wallet and nearly gave up his remaining cash but passed her his Visa instead. A charge from Twin Wells to his card might be the only evidence of his whereabouts should he vanish.

She swiped the card, then handed it back. “The new Wal-Mart in Ignacio carries shave cream. Even you can afford it there.”

“Ten miles is a hike I won’t commit to.”

She slid him the receipt and a pen. “If the bank hasn’t shut it down, you can try the Monkey Barrel. That’s Joe Newby’s place. These days, his best customers are folks without wheels. ’Course now . . . ” She shrugged and jerked her head east. “Three blocks that way.”

The Monkey Barrel was sandwiched between a one-screen theater and an antiques store, both boarded up. A foreclosure notice was taped to the window; the blinds were shut. In the alley, Baldwin scraped a trash can across the pavement and placed it below a small, high window. He stood on the lid and cupped his hand to the pane. Then he glanced around for witnesses, and though he didn’t know why and knew he shouldn’t, he wrapped his jacket around his fist and shattered the glass.

Inside, below the window, a deserted leash was knotted to the grill of a gas heater. Suddenly, Baldwin remembered a pit bull lunging on its chain in Newby’s driveway. He listened for a growl, and when he heard nothing, he dropped onto the wooden floor. He stepped forward before his eyes adjusted to the dark and tripped over a hula hoop, then a Louisville Slugger, which he picked up in case he met the dog. The cluttered toy section reminded him of his and Katherine’s living room when their boy had grown old enough to demand every toy he saw on TV.

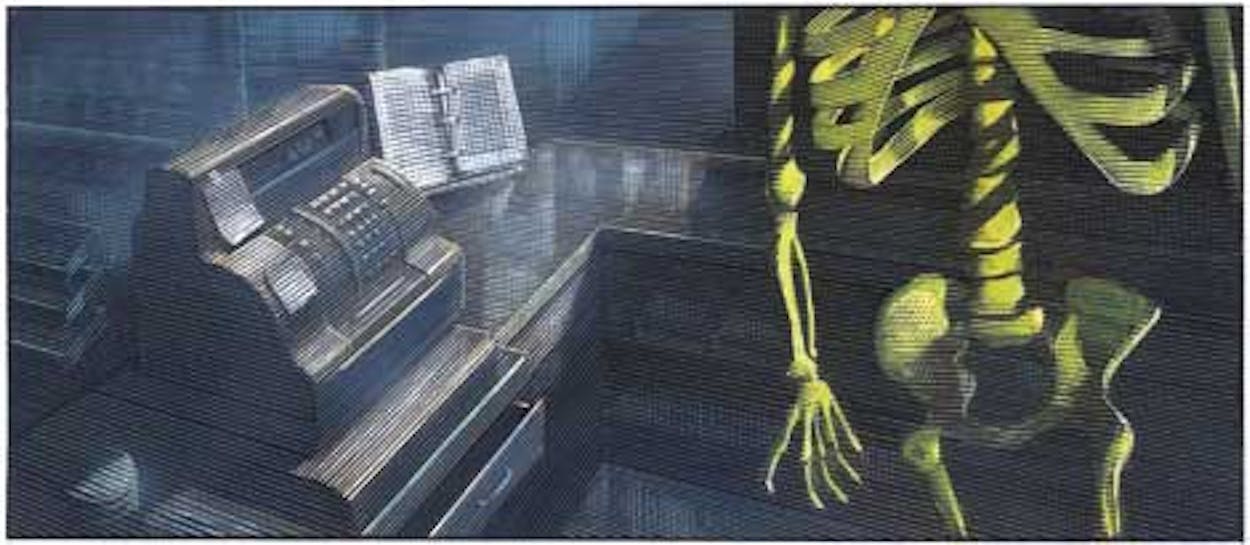

Dusty pots and dishes packed some aisles; in others, vacant pegs poked from the walls. On what merchandise there was, new price tags covered previous ones, the costs jacked up instead of marked down. In the Drugs aisle, Baldwin grabbed a can of shave cream, so old it felt empty, and tucked it in his pocket. When he looked up for the security camera, he saw paper monkeys swinging across the ceiling, their arms and tails linked. Lonely as it was, the store spooked him. Though it was mid-December, Halloween costumes—glow-in-the-dark skeletons and bloody vampires—sagged on their hooks and rubber masks watched him near the front counter.

Around the register, koozies and cans of Copenhagen were stacked high. A box of crayons was jawed open beside a drawing of a dog Newby’s son must have colored. The crooked print spelled “Pop-Tart.” “Newby’s pit bull,” Baldwin said aloud. Again, he looked over his shoulder, but only the masks stared at him. Where was that dog?

He rifled quickly through the desk behind the counter, his hands flapping through receipts and bills. He didn’t know what he was looking for until he found the metal box with the tiny keyhole. He jimmied the lock with two paper clips, and the lid popped open and banged against the counter. Startled, Baldwin thought he’d heard a car door slam and peeked through the blinds. Nothing.

Inside the box were two airline ticket stubs to Acapulco and a stack of photographs and letters that scattered on the floor when the rubber band around them snapped in half. Baldwin kneeled to gather them. One note, on purple stationery, said, “Some woman is living the life meant for me.” And another, on floral paper: “Don’t make me wish.” In an old photo, a young woman modeled her high school cap and gown. In more recent shots, she stood naked in the bedroom in Newby’s double-wide; waited, dressed to the nines, outside a hotel called the Warwick; and leaned against Newby’s truck somewhere in the desert. Baldwin recognized her from the Christmas card in Newby’s trailer: It was Sally Johnson. In the last shot, an emerald pendant dangled from her neck. The West Texas sunlight, sharp and hot, lit the rim of her collarbone, the bright edges of the gem.

Next month:

Chapter Nine, by Doug Dorst, in which Baldwin is attacked by a dog and visited by a woman with long red nails and a story to tell.