This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

It was still dark on the morning of January 2 when the meeting broke up at the union hiring hall in Houston’s navigation district. Nearly two hundred men, dressed in jeans, sweatshirts, and jackets, left the hall and piled into their cars and pickups as if to go to work. They crossed the Ship Channel at the Wayside overpass, then headed down Clinton Drive along the north side of the turning basin until they came to the road that leads to the public docks. Passing the guard station at the entrance, they continued for about a hundred yards to the foot of the S-shaped turnoff road, where they parked. Then in groups of twenty and thirty they wound their way on foot past the Strachan Shipping storage yard and behind the tin warehouses that face the water, emerging at the flat, open expanse of concrete at Public Dock 8. The men gathered in dark little knots there, in front of the Samu, a black ship that had moored during the night.

The Samu was carrying 6200 tons of Brazilian steel scheduled for unloading that morning. The men were members of the International Longshoremen’s Association (ILA), an AFL-CIO union. ILA men had loaded and discharged all ships at Houston’s public wharves for fifty years. They had not been hired to unload the Samu, however. They had come to Dock 8 not to work but, their leaders would say, to protest the awarding of the unloading contracts to Hank Milam and his company, Houston Stevedores, a firm that did not hire ILA men. But the massing of men on Dock 8, perhaps only because those men were longshoremen, gave another impression. It looked as if they had come to prevent the Samu’s unloading.

Their protest was the sort of action that at best stood on the borders of, and at worst mocked, the law. A restraining order in force for months warned the ILA against “molesting, interfering with, threatening violence or bodily harm” to Milam and the men of Houston Stevedores. That morning ILA officers had called a special meeting at the union hall, taken a vote, and passed out picket signs. They had urged their men to go to Dock 8 to protest—clearly a legal activity—and had admonished them not to obstruct the performance of work, because obstruction was illegal. The vital question was, Would they obey? When Milam and his men set foot on Dock 8, would the unionists move aside?

Waiting for Milam’s arrival beside the guard station were half a dozen of his foremen and about forty laborers he had contracted at $8 an hour from the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, which is not part of the AFL-CIO fold. One of Milam’s foremen had driven down the turnoff road toward Dock 8 shortly after the protesting longshoremen arrived. Pickets blocked his path. The foreman was convinced that if he tried to take his crew to the dock, the ILA men would attack. The situation promised to spark the biggest waterfront brawl in memory and gave the foreman reason to hesitate. He held his crew at the guard station, a quarter of a mile from the docks.

What was brewing was a classic labor confrontation. It was also a drama that epitomized the plight of unions in both Texas and the United States. Unions had negotiated and mitigated the class struggle of the thirties and forties. Even in Texas, a right-to-work state, they had organized refineries, auto and aircraft plants, meatpacking houses, and telephone companies. They had helped create a large, prosperous middle class in America, one that gave the nation political stability and insulation against radicalism. But now in the eighties, with hard times, a hostile White House, and employers poised for the kill, unions seemed to be in danger of extinction. One of the scripts being played out on Dock 8 called for longshoremen to reenact the bitter battles of their union’s rise. Another called for them to surrender to the men like Hank Milam and the economic forces that said that unions were of no use anymore.

Despite the unpopularity of unions in Texas, the ILA had gained a near monopoly as a supplier of labor to companies in the business of stevedoring, or the loading and unloading of ships. The union’s dominance extended to 36 other ports on the Atlantic, the Gulf, and the Great Lakes. Time and again it had defended its role with a willingness to strike against management and to scrap with members of rival labor clans.

Hank Milam was a small-time Houston stevedore who had less than $20,000 worth of equipment and an office in a building whose chief attraction was a deferred-payment leasing plan. In the previous nine months, by underbidding stevedores who hired Houston’s 2500 ILA members, Milam had won two dozen contracts for ships berthed in the navigation canal, but until the day the Samu moored, he had never tried to set foot in the sanctum sanctorum of the ILA, the public docks. Alone, Milam was hardly a threat to the ILA’s strength. But ever since 1981, when the nation’s president had taken on the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization and flattened it, union members everywhere had been on the alert. Following PATCO’s demise, unions like the United Auto Workers, whose employers faced Japanese competition, had been forced to forgo or postpone planned wage increases. Finally, even unions with no foreign competitors—the Amalgamated Transit Union, for example, which represented Greyhound bus drivers—had been pressed to give back the gains they had won. As the dollar grew stronger during 1984 and 1985, exports continued to decline, and because the oil market had gone to pot, Houston’s maritime traffic was in a slump. Every time Milam underbid a unionized stevedore, managers of competing companies demanded that the ILA take cuts in work gang size, benefits, and pay. Milam’s activities had inspired non-ILA stevedoring operations in other ports. The Samu had already called in Tampa Bay and New Orleans, and it had been unloaded in both places by non-ILA laborers. If Hank Milam wasn’t stopped, Houston’s ILA men believed, the union would be imperiled from Texas to Maine.

Milam Declares War

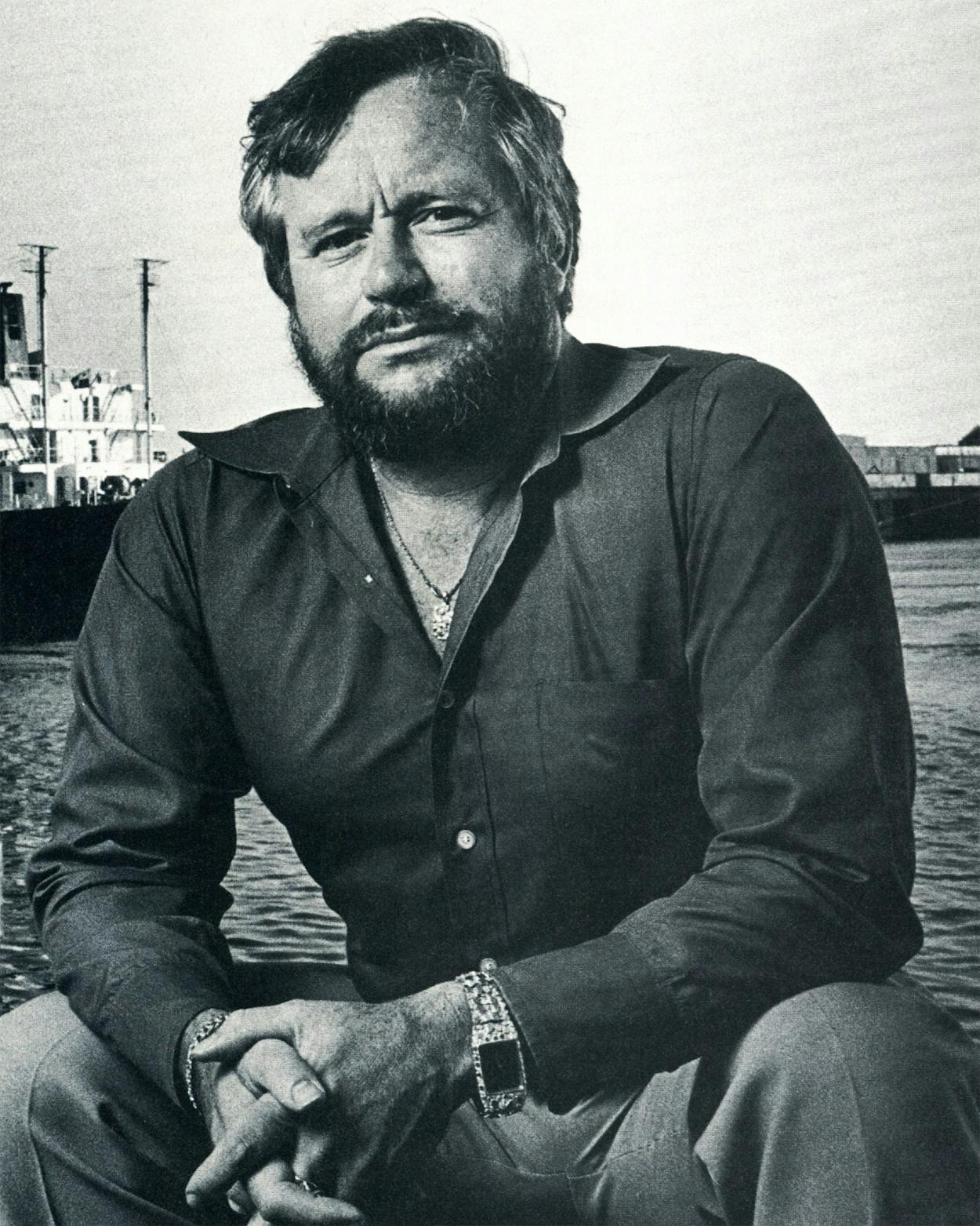

Henry E. “Hank” Milam, 39, is squat, pink-faced, blustering, brown-bearded businessman. He was born in Kentucky, where his mother is a union worker in a baked goods factory. After earning a journalism degree in his home state during the late sixties, he served a tour of duty as an Army intelligence sergeant in Korea, then returned home to manage an uncle’s trucking company. Through connections he made on a golf course, he arranged to become an executive for Dixie Stevedores in 1978, and he moved to Houston to begin the job. He was appalled by the double-digit wages that Dixie and other union stevedores grudgingly paid union men. “It didn’t take a lot of intelligence to see that people were being hired all over town for six to eight dollars an hour,” he says. “But nobody had the guts to bring them to the waterfront.” In March 1984, with $2000 that he says he borrowed from a friend, Hank Milam founded Houston Stevedores. He hoped to get rich quick by outmaneuvering the ILA and its client companies.

The President’s Commission on Organized Crime has cited the ILA as a union under mob influence, if only because leaders of some New York–New Jersey locals had personal business ties to suspected mafiosi. But the specter of becoming the target of a Mafia hit team didn’t deter Milam. He declared war by circulating brochures that offered stevedoring services at rates 25 to 50 per cent below those of established ILA-employer firms. “I didn’t have to base my prices on cost,” boasts Milam. “ I based them on competition.” But shipping lines and cargo owners were reluctant to tempt the legendary and seemingly invincible ire of the ILA. During his first year of business, Milam won contracts to handle cargoes, but only on ships that were safely berthed at out-of-the-way private docks. In April 1985 he bid to load 17,000 tons of grain onto a ship called the Lone Star. His bid, 55 cents a ton, was about a dime per ton below the bids of his competitors. The owners of the cargo gave Milam the stevedoring contract, even though the ship was to be loaded at the Cargill grain elevator, an important private facility just inside the Ship Channel waters traditionally worked by the ILA. On the morning when Milam and his crew, all nonunion men, arrived to load the Lone Star, about fifty ILA pickets stood at the entrance to the elevator. Milam’s tactical and business sense told him that his men didn’t need to charge the picket line. He hired a helicopter to fly them onto the ship and off, and he still made a handsome profit. Hank Milam had won his first skirmish with the ILA, and by the measure of Gulf maritime affairs, it was historic; fifty years had passed since non-ILA men had loaded any grain ship in the region’s deepwater ports.

Two months later eight employees of Houston Stevedores returned for another job at Cargill. They came to load the General M. Macleef, an Israeli vessel. No pickets awaited them, and they began work straightaway. But as they were eating lunch aboard the ship, at least fifty ILA men came up its gangplank. They cut the cables on Cargill’s loading chutes and with punches, threats, and shoves ousted Milam’s crew. The following day Milam went to court, asking for a restraining order against the ILA. When the damage at Cargill had been repaired, Milam’s men returned under court protection to finish loading the Macleef. Completing the job was a second win over the ILA. The restraining order, Milam believed, was his biggest victory yet. It made clear to everyone that the law was on his side.

Milam then was ready to take his crusade to the public docks to unload the Samu. One of the lieutenants he chose for the operation was Grant Akers, 31, a burly, hard-drinking, black-haired foreman for Houston Stevedores and a veteran of the Cargill skirmish. Akers was committed to Milam’s cause with the zeal of a convert—or a turncoat. For several years, though he never signed a union card, Grant worked out of the ILA hall on Harrisburg Boulevard, sharing in the jobs the union dispensed. He had come from a union family, which he says is now beset with “something kind of like a civil war.” after Grant joined Milam’s raiding party, his father, an ILA retiree, quit conversing with him. Grant’s grandfather was Floyd Akers, an ILA member and veteran of the Gulf waterfront war of 1934–35. That conflict had first given everyone on the waterfront—union and management alike—a deserved reputation for brutality and lawlessness.

In two on-again, off-again strikes in 1934 and 1935, company guards, ILA men, non-ILA dockworkers, and assorted strikebreakers battled to exhaustion, time after time. In packs of a hundred, union men charged the Cotton Exchange building, where strikebreakers gathered every day to ride through Houston’s navigation district—practically a shooting gallery—in armored trucks. When the vehicles were fired upon, guards fired back. Both sides ignored warnings from their foes and scoffed at court orders. When their partisans were arrested, both sides hired lawyers who helped even the guilty enter self-defense pleas. The strike spread east to Mobile, Alabama, and west to Corpus Christi and was violent everywhere. “We learned pretty quick that if you broke a scab’s arm or leg, he wouldn’t show up for work the next day, but if you only bloodied his nose, he’d go anyhow,” recalls Gilbert Mers, 78, an ILA survivor of the strike. To ride herd on the feuding dockers, the City of Houston hired a special force of 41 policemen, and the port authority called in Frank Hamer, the former Texas Ranger credited with the ambush of Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker, as chief of security operations. Despite those measures, five of the strike’s thirteen killings occurred in Houston.

The Frustration of Young Men

Calvin Akers, 33, stood with his fellow unionists at Dock 8 on the morning of January 2, waiting for his cousin Grant to come down the turnoff road with the other men from Houston Stevedores. Calvin is a tall, thin man with strawberry-blond hair. He kept an eye out for Grant because he had a bone to pick with him. Dock 8, Calvin thought, was the appropriate place. Like Grant, Calvin is a grandson of ILA progenitor Floyd Akers, but Calvin has remained steadfast to the family’s union tradition. Calvin is grateful to the ILA; because of the union, he says, his and other longshoremen’s families have been able to partake of the nation’s prosperity. Calvin has not been able to vacation in Cozumel, as bachelor Grant has, nor have he and his wife, Michele, been able to travel outside of Texas more than once. They don’t own a powerboat or a lake house or a Bronco or any of the other coveted totems of working-class life in East Texas. But they have been able to rear their three small children in a brick house in a wooded suburb, and thus far, Michele hasn’t had to seek work outside the home. Calvin believes that not only his union wage but also his willingness to work has made his relative security possible. “I’ll take any job I can get, even slinging bags of rice, and no matter how cold it is, I’ll go to work because I know I’ve got to work to live,” he says. Grant, Calvin maintains, was afraid of hard work long before he left the union fold. “Grant’s problem is that he’s just sorry. He didn’t want to do the kind of hard work we have to do. He left the union because those other guys offered him a soft foreman’s job.”

The real difference between Calvin and Grant Akers has less to do with class, family loyalty, marital status, and an inclination to avoid work than with the fact of dates. Calvin quit high school at seventeen, went to work on the docks, and got married. The year was 1970. Grant, who is two years younger, finished high school, went to college for two years, then spent several years at an inland job. He didn’t decide to become a longshoreman until 1978, eight years after Calvin did.

ILA jobs are meted out by seniority. The concrete floor of the union hall is divided by strips of yellow vinyl tape into large squares, each marked with a number corresponding to years of seniority. Each morning ILA crew foremen step out from behind a glassed-in enclosure onto the floor, clipboards in hand. The papers on the clipboards carry notations about the names, locations, and cargoes of ships and the number of longshoremen, winchmen, crane operators, and truck and lift drivers needed for each job. Men get to choose their jobs, but the picking starts at the high-seniority end of the floor, and the distance is great: Texas ILA workers average 49 years of age, and many have 25 years on the docks. In good times the seniority system is benign. Senior longshoremen claim the easiest jobs for themselves, but there are jobs for everyone. In bad times it becomes painfully evident to younger men that the union, which is supposed to wrest an equitable deal out of the waterfront’s economic system, has imposed a hierarchy of its own. Plutocracy may rule the waterfront, but gerontocracy rules the union hall. Grant Akers began standing on a numbered square at the union hall during the oil-and-inflation-fueled boom of the late seventies. When the bust came and he hadn’t advanced to a number high enough to be safe from the scarcity of jobs, his association with the ILA no longer made sense to him.

In 1979, 117 million tons of cargo moved through the Port of Houston. By 1983 that figure had dropped below 90 million tons, and by 1985 it was under 75 million. But tonnage figures don’t include the weight of cargoes such as bulk petroleum—cargoes that longshoremen don’t touch—and thus fail to show the depths of the depression that has descended on Houston’s docks. General cargo movement and steel imports—big job sources for longshoremen—have fallen to half the levels of the late seventies. Grain exports have declined by nearly three quarters. The total number of man-hours worked by ILA members in the area from Lake Charles, Louisiana, to Brownsville dropped from a high of 9.9 million in 1980 to 5.2 million in 1985.

By 1985, when Grant Akers abandoned the ILA, he had accumulated enough working hours to qualify for only four years of seniority. His wages had fallen from about $25,000 a year during the boom to below $18,000. Calvin, on the other hand, had fourteen years of seniority. In 1985, a year of job drought on the docks, he logged about 1800 hours at work, an average of 36 hours per week. His paychecks totaled $39,000. “I blame the union for not spreading out the work to low-seniority men,” Grant says. “The trouble with Grant,” Calvin says, “is that he didn’t go to work when he could have.”

The frustration of young men like Grant Akers is traceable to the seniority system, but the loyalty and affluence of young men like Calvin Akers can be explained only by taking into account the paradoxical success of the ILA as a union. Senior ILA men owe their security and comfort to the threat of automation. The 1934–35 strikes established the union as a permanent fixture on the waterfront but did little to improve the longshoreman’s daily life. The factor that made the ILA the dominant force in waterfront labor-management relations was the introduction in 1956 of the shipping container, an innovation that threatened to decimate the ranks of dockworkers. The specter presented the ILA with an unfeeling, visible foe, with a device for uniting its members in militant opposition to mutual extinction.

The shipping container is a metal box, originally eight by eight by twenty feet in size and now sometimes twice as long, in which fifteen to twenty tons of almost any cargo can be stored. Though the container came late to commodities, cotton—until recent years a big Texas export—offers telling evidence of the container’s power. In 1935 and for more than thirty years afterward, cotton was stowed on ships by the sling method. Whereas Houston stevedores could load 200 bales of cotton per hour with slings, they can now load 1100 bales of containerized cotton in the same amount of time. Shorter loading times mean reduced hours for longshoremen, and reduced hours, when filtered through the ILA’s seniority system, spell friction between younger and older union men.

Containerization gives rise to friction between unions too. Traditionally, dockside warehouse work is performed by members of the ILA. Inland warehousemen usually belong to the Teamsters. Since containers can be swiftly and cheaply transported inland, the work of packing and unpacking them, called stripping and stuffing, need not take place on the waterfront. The container makes the site of warehousing AND unions a matter of choice, a choice of geography and of unions. It pits ILA men against Teamsters, Teamsters against ILA men, wage scale against wage scale.

Because containers can be lifted by cranes from a ship directly onto a railroad car or a truck, containerization has created competition among ports. Today it is cheaper to import many cargoes through Atlantic ports for rail transfer to Houston than it is to bring them by ship across the Gulf. Containerization has made choosing a point of import or export less a question of geography than one of pure cost. It has pitted port against port.

Containers also exacerbated an accident of world economic history. The globe’s developed nations lie along an east-west rather than a north-south axis. Containers and their cranes were expensive technological innovations; they came into use, first and foremost, in trade between industrial nations. The biggest U.S. container-handling ports are on the Atlantic and the Pacific coasts, not on the Gulf, whose characteristic business has become the exchange of noncontainerized mineral and agricultural goods with Third World nations. Containerization threatened Atlantic and Pacific dockers with the loss of their jobs to automation. It threatened Gulf dockers with a loss of their jobs as a result of the decline of their ports.

The ILA’s fight against the effects of containerization began in 1964, when the union struck for the privilege of dictating the size of work gangs, a power formerly reserved for stevedores. The struggle continued throughout the sixties with efforts to impose a royalty on every container to be paid into pension funds and plans that guaranteed every ILA member a full, 52-week salary, regardless of the availability of work. The fight broke out again and again over demands that shippers hire ILA men and not the cheaper Teamsters for all stripping and stuffing performed within a fifty-mile radius of ports. Though Houston’s ILA men had to back their demands with a 101-day strike in 1968 and 1969, the union was victorious from Maine to Texas. The ILA won because the Vietnam War, inflation, and a vigorous domestic economy boosted international trade and induced a labor shortage. It also won because management knew that the union’s victory was Pyrrhic; containerization proceeded, and that meant that the future belonged to fewer longshoremen than had been needed in the past. The ILA’s strategy was aimed at protecting the status of its veteran members, men like Calvin Akers, not at ensuring future jobs for men like his cousin Grant.

The triumphant ILA soon became arrogant. It won sixteen holidays for its members, including the birthday of Thomas W. “Teddy” Gleason, Sr., its longtime international president. It required stevedores to hire ILA winchmen and flagmen who weren’t needed on every ship. Waterfront-wise seniors often signed up for two featherbed jobs at a time, collected two paychecks for a single eight-hour shift, and sometimes didn’t present themselves for work at either one. “Double-dipping,” as the two-check scheme was called, disappeared during the late seventies, when waterfront payrolls were computerized, but another featherbedding tactic, double-barreling, continued. “I’ve seen times,” Grant Akers says, “when there would be eight men sent to work on a vessel whose holds didn’t have room for more than four. The extra four would just sit around, double-barreling, doing nothing. But they were still on the payroll.” About a fifth of the 11,000 longshoremen from the Port of New York–New Jersey, largely a container port, are now living without working at all, on the basis of checks from the union’s guaranteed annual income program. To finance the plan and an increasing pension burden, the ILA hiked the rates for employer-paid benefits. Today Calvin Akers earns $17 an hour in wages, but to hire him, employers must pay an additional $6.50 an hour into ILA benefit programs. When all labor expenses are tallied, including workmen’s compensation and insurance, it costs about $35 an hour to employ an ILA longshoreman. Hank Milam brought his Teamsters to the public docks on January 2 for a total of $13.50 an hour.

A Prophet of Capitalism

It was nearly sunup when Hank Milam arrived at the guard station at the entrance to the docks. From where he stood, Milam could see the vehicles of protesters parked at the turnoff road, and from the reports of his foremen he knew that the ILA force was unruly and large. Hank Milam was caught off guard. He had expected a picket of perhaps fifty men, like the line he had crossed by helicopter at Cargill. But he had thought that his restraining order would prevent the unionists from massing or menacing; after all, hadn’t it kept them from returning to the General M. Macleef? What Milam believed was that the union’s leaders wouldn’t allow their men to violate the terms of the restraining order. By his lights he had won every encounter so far, and he intended to win again. If the gathering on Dock 8 wasn’t legal, Milam reasoned, the wisest move was to have it dispersed by the police. With a foreman at his side, Hank Milam went running to the Port Authority’s security office, about half a mile from Dock 8.

The port’s chief of security hadn’t come to work yet. Milam telephoned him at home. When the security chief arrived at the turning basin, he decided that it was a problem bigger than his men could handle. He called the Houston Police Department, whose plainclothesmen did not arrive until about nine-thirty. The HPD officers, after sizing up the looming confrontation, decided that the men on Dock 8 could be dispersed, but only by riot cops. They promised to have a sufficient number of crowd-control officers gathered at the guard station by two o’clock.

The call for riot cops drew television, radio, and newspaper reporters to Dock 8. Men and women of the press, in sport coats and khaki pants and skirts, milled among the men in jeans, interviewing those who would talk. Hank Milam smothered his rage. He spoke in the politest terms. The confrontation over the Samu, he said, arose because the ILA “would prefer to maintain a monopoly, and I would prefer to make the waterfront independent and competitive.” He spoke expansively and in a spirit of nearly amused optimism, explaining his views on business and unions, frequently invoking the word “competition.” In a way, the arrival of the press was Hank Milam’s hour. It gave him a chance to take his crusade to the public, and it let him speak as a prophet of capitalism.

The morning passed slowly. In the early afternoon Milam and the reporters watched as longshoremen brazenly began laying a barricade. The ILA protesters took trucks, forklifts, and shipping containers from the Strachan Shipping storage yard and placed them across the turnoff road. Shortly after two, as they hastily finished their fortifications, nearly twenty blue-and-white patrol cars and several unmarked cars carrying plainclothesmen came into the turning basin and halted around the guard shack. Other patrol units took positions at both ends of Clinton Drive, sealing off the area. About forty black-suited riot cops began adjusting their helmets with face shields, securing their canisters of tear gas, cinching the straps of their plastic shields. All of the elements for Milam’s victory seemed to have come into place. He had a restraining order, which prohibited the ILA’s interference. He had contracts authorizing him to unload the Samu. And with the arrival of the riot cops, he had enough troops to clear the protesters from Dock 8. There seemed to be no reason, in law or in tactics, why he should not proceed. Milam was ready to move in.

A Battle of Nerves

Hank Milam wasn’t the only man with a stake in the Samu dispute. Shortly before the riot police pulled up at the guard station, Le Roy Bruner, president of ILA Local 24, still in his offices on Harrisburg Boulevard, decided that the protest on Dock 8 had gone on long enough. Bruner, 49, is a short, brown-haired resident of Pasadena with the guarded demeanor and cautious mind of a deacon: he is a deacon, at Houston’s Allendale Baptist Church. He is also the son of an ILA man and the nephew of no fewer than seven ILA men. As president of the union’s local, Bruner had early that morning asked his members to protest the Samu’s arrival. But he hadn’t asked them to prepare to fight. Bruner, as Milam had suspected, wasn’t ready to go to jail. As he drove from the union hall down Wayside on his way to the docks, Bruner tried to find the words to ask his men to concede the Samu to the men in Hank Milam’s crew.

This wasn’t the first time he had gone to ask his men for concessions. It seemed to him as if he had been doing nothing else for months, ever since Milam’s rise in Houston and the emergence of non-ILA stevedores in other ports. To help ILA employers compete with Milam and to help the Port of Houston compete with New Orleans, where union concessions had also been made, Bruner and the Houston ILA had agreed to substantial cuts in the size of work gangs. They had also made miscellaneous concessions on a day-by-day, ship-by-ship basis. But even their concessions had not stopped Milam’s forward march.

Bruner’s acceptance of the tactic of retreat was the mark of his brand of unionism. Fifty years ago, when most union men were brawling with guards and strikebreakers to establish their organizations, the labor movement was an evangelistic, nearly millenarian cause. Union spokesmen, by and large, were syndicalists, radicals, and socialists; some were thoroughly red. In the eyes of left-leaning leaders, union halls were not places of business but church houses, places to preach a doctrine and gather a congregation in pursuit of aims that lay not in the present but in a future, more egalitarian world. The union movement in those days, if it wasn’t realistic, was at least inspired. Advocating concessions was akin to advocating sin.

The debate over radicalism had started early in the ILA. In the mid-thirties its West Coast locals, led by the leftist Harry Bridges, in defiance of instructions from the union’s New York headquarters, had precipitated general strikes and participated in sympathy strikes, especially with seamen. By 1937 East-West relations in the ILA had grown so tense that Bridges bolted the ILA, establishing a new Pacific dockers organization, the International Longshoremen’s and Warehousemen’s Association. Stung by the loss of the union’s western membership, ILA leaders helped spur the drive to purge radicals from labor’s ranks, a process that began at the onset of World War II and was completed in the mid-fifties. The deradicalized union revived an older, more moderate school of union philosophy, sometimes called business unionism. Le Roy Bruner was a product of that outlook.

Advocates of business unionism regard themselves as salesmen of a commodity—labor—in an economy whose ground rules are essentially beyond question. The business unionist sees his role as one characterized by research, persuasion, mediation, and compromise; sincerity, brawn, and lawlessness are the weapons of the radical school. Le Roy Bruner, because he was a business unionist, did not feel that he had betrayed or failed his men by going to them with proposals for compromise. He was quite sure that the rise of Hank Milam was not because of evils inherent in the economic system but because of the decline in maritime commerce.

But advocating concessions was dangerous. Bruner had learned that union members are apt to distrust leaders who, like most ILA officers, live in relative ease. It had been more than ten years since Bruner had quit working “off the floor” to assume the white-collar duties of a local vice president. As the local’s president for a year, he’d earned an annual salary of $93,000—enough to make him suspect. In November Le Roy Bruner will face reelection. He already knew that there were men in his local who believed that he hadn’t taken a hard enough line with management. And Bruner had a special problem: his union critics included Teddy Gleason, the ILA’s 85-year-old international president. In September, with Bruner’s support, Gulf locals had voted to forgo a $l-an-hour raise for work on grain ships. But wages are one of the items in a seven-point master contract, uniform in all ILA ports, that is negotiated in New York by a committee of national union and management leaders. In late September, Gleason and the International, as the union’s New York headquarters are called, had rebuked Gulf leaders for undermining the master contract and had ordered ILA locals to accept the wage hike, whether they wanted it or not. Thanks to hard times and Hank Milam, Le Roy Bruner had become a union leader who couldn’t count on support from above or below.

Bruner arrived at Dock 8 about the time the riot squad was suiting up. He shook hands and chatted briefly with two or three union members, then stepped onto a pickup bed to address his men. In his measured, cautious deacon’s style, he told them that the ILA had a long history and a big investment on the docks, and he talked about the virtues of lawfulness and the need to preserve a businesslike image. “You can say what you want,” he told the protesters, “but we need to move out of here in a right way.”

The men were skeptical. Not all of them believed, as Bruner insisted, that the union could hold its ground by resorting only to means within the law, such as protests and boycotts and strikes. Not all of them were inclined to take their leader’s admonitions at face value either, because the docks are a special place. They are a place like the borderlands, where law and actuality are customarily different. On the border the most common attitude toward the law is expressed in a series of questions: “What law? Who enforces it? How likely is enforcement?” All deep-sea ports are borderlands too. They are places where men make deals and depart, usually before the long arm of the law can roll up its sleeve.

The longshoremen hesitated for another reason. Most of us work at jobs in which we have little reason to fear the future. We are sure that economic terms like “strong dollar” and “balance of trade” have some relation to us, but since we live in a workaday world largely made in the USA, we are not exactly sure what those terms might mean. Longshoremen are no better economists than the rest of us, yet every day when they go to the hiring hall, those vague economic terms determine whether longshoremen work today or hope for tomorrow. The strengthened dollar, more than any other factor, has minimized Houston’s grain exports because Third World countries can’t afford to buy our grain anymore. But longshoremen can’t find consolation or a scapegoat in the economists’ lexicon. Incorporeal demons can’t be fought; cops and men like Hank Milam can. Most of the protesters on Dock 8 had decided not to square off with the riot squad—they figured that they would lose if they did—but they had also resolved not to back down until faced with an actual physical threat. They weren’t ready to surrender in what thus far had been only a battle of nerves. “I figured that the police would settle the whole thing,” Calvin Akers says, “but they hadn’t come down there yet.” When Bruner finished his speech, a few seconds passed in silence, and then someone in the crowd yelled, “We’re staying right here, where our jobs are!” The cry was met with clinched-fist salutes and shouts of approval. A dismayed Le Roy Bruner looked into the cheering crowd, then stepped down from the pickup. He left Dock 8. The longshoremen stayed.

Unknown Forces

As Le Roy Bruner drove off from the turning basin on his way back to his office, he passed the guard station. Plainclothesmen were in a huddle there, talking to Hank Milam. They had taken a count of the protesters, about 260 of them in sight and perhaps as many as two dozen more lurking in the tin warehouse at Dock 9. Numerical superiority wasn’t on the lawmen’s side. “We were outnumbered and so was Milam, and the mood of those longshoremen was not conducive to peaceful resolution,” recalls police captain M. C. Simmons. Furthermore, the lay of the land—the barricades and storage area, the scattered containers, and the open warehouse—was not favorable to a sweep. There were too many places for the dockers to duck out of the way. Any incident on the dock would take place in the full view of the press and might embarrass the whole waterfront business community, not to mention the police. The cops decided not to clear the dock. Milam was infuriated. “Had they wanted to go down there and bust up that situation, they could have,” he grumbles. “But they were afraid of getting caught in the middle. They were afraid of public opinion.” But Milam didn’t argue with the policemen. He kept his composure. After all, he was on TV.

Outmanned, outsmarted, and feeling betrayed, Milam could think of only one recourse, to reach deeper into the recesses of law. All day he had been consulting his lawyer by telephone. Their plan was to rush into court, asking a judge to turn the restraining order into a permanent injunction—and to cite the ILA for contempt. Milam hoped to make his legal points before the end of the day and to unload the Samu by artificial lighting, if necessary, at night. About three, he left the turning basin for his attorney’s office downtown.

Unknown to Milam and the men on Dock 8, forces outside of Houston were already being brought to bear on the situation. In New Orleans shortly after midnight on January 2, Dale Revelle, 31, had gotten into his blue Ford mini-pickup and begun the drive to Texas. Revelle, a black-haired man who looks like a marine, is representative of the Commodity Ocean Transport Corporation of New York (COTCO), the firm that managed the Samu. Revelle’s purpose in coming to Houston was to see that the ship’s loading was accomplished quickly, because an idle ship meant idle capital. Minutes after his arrival in Houston at about sunup, he and another ship’s agent had crossed the ILA’s picket line, boarded the Samu to confer with its captain, and as they drove away, passed through a hail of bottles and junk. The ILA men at Dock 8 apparently were blaming the ship’s agents too for their troubles with Milam and the Teamsters.

Revelle felt as if he and the owners of the Samu were bystanders to the Dock 8 conflict and its victims. In the liner trade, ship owners usually select stevedores. But the Samu was a tramper, and most of its cargo was being carried under “free in and out” contracts that left stevedore selection to cargo owners, agents, and brokers. He wanted to see that the Samu got a quick turnaround, and the face-off at Dock 8 was causing delay. The rowdiness Revelle had seen that morning convinced him that if the ILA didn’t win the battle for the Samu, bloodshed—and more delay—were inevitable. He had gone to the waterfront offices of a Houston stevedore to use a phone, and from there he had reported his observations to COTCO’s New York chieftains. Revelle expected them to persuade the owners and agents of the Samu’s cargo to back away from their contracts with Milam.

Control from offices in New York has long been a fact of Gulf waterfront life. Most of the nation’s container companies, shipping lines, and export-import handlers are based there. The classic case of intervention from New York dates back, as does so much else on the Houston waterfront, to the 1934–35 strikes. When New York’s ILA locals, who were not on strike, voted to boycott the ships of any lines that had not come to terms with the union in the Gulf, the threat brought immediate results. Not being able to do business in Houston was a minor inconvenience to most lines, but not being able to do business in New York was cause for crisis. The New York home offices of national shipping firms sent telegrams to their Houston affiliates, ordering capitulation to the ILA and ending the dispute.

While waiting in the offices of Houston stevedore Doyle Varner for orders from New York, Dale Revelle also called Houston ILA leaders to invite them for a talk. By late afternoon more than half a dozen, including Le Roy Bruner, were gathered in Varner’s offices for the powwow with Revelle. The union leaders fidgeted on the couch or paced about uneasily because they were accustomed to regarding their host not as a friend or partner who deserved to be privy to their business talks but as an opponent and employer. Varner, 57, is a big, silver-haired man, an executive since 1958, and now head of Houston-based Empire-United stevedoring firm, one of the biggest ILA employers on the Gulf. Varner had allowed Revelle to use his office out of courtesy, and his attitude toward the COTCO agent’s talks with the union was one of aloof neutrality.

Varner recognized the desperation of Bruner and other ILA leaders to score a victory on Dock 8, but his sympathies weren’t easily swayed. He felt in many ways as if the ILA had invited trouble by abusing its contracts and clout. On the other hand, Varner recognized an opportunity to squeeze one-time concessions and maybe long-term goodwill out of the ILA—something a stevedore needs whenever a ship comes in.

When the union men asked him to be ready to discharge the Samu, Varner demurred. The proposition wasn’t promising, he said, because at least two of the cargo owners and brokers had contracted with Milam at rates that a stevedore employing ILA men couldn’t match. If he was going to arrange for the unloading of the Samu, Varner said, the ILA would have to make concessions for the job. His wish was granted on the spot.

About sundown Dale Revelle, now safely accompanied by Le Roy Bruner, again boarded the Samu, this time to look over its cargo with an eye to unloading arrangements. While the two men were in the hold of the ship, word reached them from New York that the cargo owners and brokers had agreed to bolt their contracts with Milam. Le Roy Bruner leaped to the deck of the Samu, then scurried down its gangplank. Standing on a level with the men on the dock and under the lights of a television camera crew, he announced the ILA’s victory. “Why did the cargo owners change their minds?” a reporter asked him. Bruner hesitated in the prudent manner of a deacon who’s been asked to confess his sins and then with the slyness of a politician quipped, “I guess you could say that they decided that in the long run we would do the best job.” The ILA men on Dock 8 roared with laughter. Their president, they decided, was a hero after all. He had won the day and had made a fool of the press. Anybody on the waterfront knew that the cargo owners and brokers had changed their minds not because the ILA was more efficient than Milam’s men but because its numbers were greater and its men were bolder. Unlike the crew from Houston Stevedores, the ILA men knew how to prepare for a fight.

The Rule of Law

Hank Milam’s defeat at Dock 8 on January 2 was not nearly so bitter as it seemed. In a way, Milam had won: the terms of his surrender were so sweet as to be attractive. The broker for the bulk of the Samu’s cargo had paid Milam in advance. Milam had contracted to unload most of the ship’s steel at the rate of $10 a ton. When Doyle Varner telephoned Milam’s house to tell him that the cargo was being reassigned, Milam stood his ground. “I told him,” he says, “that I was willing to subcontract the job to him, but at six dollars a ton,” a figure below Varner’s profitability floor, even with ILA concessions. Varner, who says he never does anything out of the goodness of his heart, agreed to take the cargo to win goodwill from the ILA.

Milam made $18,400, while his competitor took a loss to unload the ship. He didn’t give up his effort to bring the rule of law to the docks. In late January he won an injunction governing future encounters with the ILA. Its terms were restrictive and in some ways unique. If the union was to mount protests, as it had done on January 2, it was required to keep all its supporters 150 yards from Milam and his ships and to videotape protest actions for perusal by the court.

The public notice generated by Milam’s scrapes with the ILA, on the docks and in court, was good advertising. In some quarters, he became a folk hero, the entrepreneur of the hour. Milam’s office was deluged with inquiries and congratulations from cargo receivers, some from as far away as New England. Although several ships he had contracted backed away from using his services after the brouhaha on Dock 8, Hank Milam’s chief business problem became not winning contracts but a shortage of capital for expansion. In early February Milam opened a Houston warehouse, putting non-ILA men to work stripping and stuffing the containers that passed through.

He also began operations in New Orleans and Mobile, and in March he opened offices in both ports. With supervisors from Houston and locally recruited Teamsters, his company unloaded a ship on the public docks in New Orleans—unthinkably, on Mardi Gras, an ILA holiday. In late March, Milam announced plans—which so startled the maritime shipping community that the story was carried on the front page of the Journal of Commerce, the shipping industry’s daily—to begin doing business in the Port of New York–New Jersey, the hallowed ground of the International. Two months after he lost the Samu, Hank Milam could boast that he had become the biggest non-ILA stevedore in the nation. The honor was a small one, but it took on new significance with every passing week. The organization of non-ILA stevedores that Milam and his cohorts had inaugurated in late 1985 had by the spring of this year claimed a total of 22 public affiliates and an undisclosed number of covert members. Waterfront businessmen speculated that the closet membership was an indication that companies bound by ILA contracts were about to father secretly owned subsidiaries that would hire non-ILA longshoremen. “Double-breasting,” a tactic used in the construction industry to foil government minority hiring and prevailing wage rules, was on the agenda for companies that work the docks.

Milam had also sparked an aboveboard counterrevolution. On January 24 the West Gulf Maritime Association announced its refusal to join other employer groups in new ILA master contract talks. Within two weeks, employers’ associations in New Orleans, Mobile, and eastern Florida joined the boycott. By the end of February only four management groups remained in the dozen-member committee that had negotiated previous master contracts, and even they postponed the opening of contract talks.

In early April, as the whole maritime industry watched, Houston’s ILA longshoremen and negotiators for the WGMA began their own round of talks. On April 9, while the ILA and the WGMA were cooking up their new deal, Milam’s men again challenged the ILA on the public docks. A grain barge, the Producer, was pushed into port by a tugboat out of New Orleans. The barge was to be loaded at Dock 14, site of a public grain elevator, with wheat bound for Haiti. On the morning of April 9, policemen escorted Hank Milam’s men to work, barricaded the dock, and encircled the ship with as many as fifty patrol cars. Nobody but cops and Milam’s men reached the barge—except for two representatives of Doyle Varner’s company, Empire-United. Varner’s men offered the tug’s captain a competitive loading rate; he spurned them. Half a dozen ILA pickets stood by, at a safe and legal distance, for three days while the Producer took on its cargo. Milam’s men completed their work, and the barge was towed out of port without incident.

Milam had won, and he had won on ILA turf—the public docks. Ten days later, on April 21, Houston’s ILA men voted to accept what amounted to a new contract, much of it effective immediately, which granted such large concessions that it was hailed as a “landmark” contract; the base wage was reduced to $14 an hour. The locals were ready to compete with Milam, but there was the question of whether the International would approve the contract or whether it would ask the ILA rank and file to vote for a strike in the fall. And there was the still larger question of whether the union would survive.

Like most other American unions, the ILA is now on the defensive. Yet it is important to recall that strong organizations like the ILA were built not on the general conditions for labor but as a defense against specific threats, such as the container. The evangelistic fervor of the union movement, without which many participants thought unions could not survive, has been gone for thirty years. Yet unions endure despite declines, as churches have endured. Billy Sunday died, but he has been superseded by evangelists of the electronic church, and nothing stands in the way of a future revival of unionism.

For the ILA, that revival may come this fall, when a national ILA referendum could force Houston’s union longshoremen out on strike whether they want it or not. If a strike comes, Hank Milam will replace the shipping container as the inspiration for the change. Union and management leaders are predicting that a strike won’t happen, but then they always do. Prudent, self-interested men don’t predict strikes or hurricanes. Like mayors of coastal tourist towns who don’t want to speculate about the possibility of hurricanes, union and management men don’t speculate about strikes. But strikes and hurricanes do happen, and on the waterfront both are potentially deadly and damaging.

The most likely beneficiaries of a fall ILA strike—in the short run anyhow—are non-ILA stevedores like Hank Milam. Most of them are already making preparations to get rich quick. They have made money by underbidding competitors who hire workers from the ILA, and now they are ready to make their fortunes when those employers are struck by the ILA. When union and management disagree, entrepreneurs like Hank Milam make bucks.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Houston