I walked the ground of Texas in the drought of 2009—from here in Vermont, where I have lived for fifteen years. I couldn’t get away from it. I’d be strolling along Lake Champlain, and all of a sudden I’d be back on the Edwards Plateau, watching the bluestem and buffalo grasses turn brown, the hackberries crack rocks with their roots in search of a trickle of springwater. I’d wake up in the middle of the night and be stumbling down a gully in the Panhandle fretting about the Ogallala Aquifer. It became clear that when I’d left the state of Texas, in 1981, my feet had stayed behind.

The first time my family moved from Kentucky, it was to Houston, and I was in first grade, or maybe kindergarten—there was dispute. But I didn’t really get to know the state of Texas till my daddy, a geologist, got tired of working indoors for the Shell research lab and settled us in Midland, where he could get back out in the field. At first it seemed like any school anywhere: My new friend Jean and I climbed trees; my classmate Kingsley and I argued over who was the smartest kid in third grade, and I beat up his best buddy to show him. But as far as the physical world was concerned, I had landed on a different planet. I can remember struggling to walk home in the afternoon, my hair dry as straw, using the bottom of my skirt to filter out the driving sand, which whipped like a lash across my skin, blinding me and filling my mouth. At home, we drank distilled water from huge jugs that only my parents could lift, and my mother kept a pan of tap water evaporating on the stove all day so the air wouldn’t be too dry to breathe. Sand seeped under the doorsills. Water, I came to see, was what this adopted state was about—not oil, as my daddy got paid to think. Not refineries and the pumps we called grasshoppers, but water.

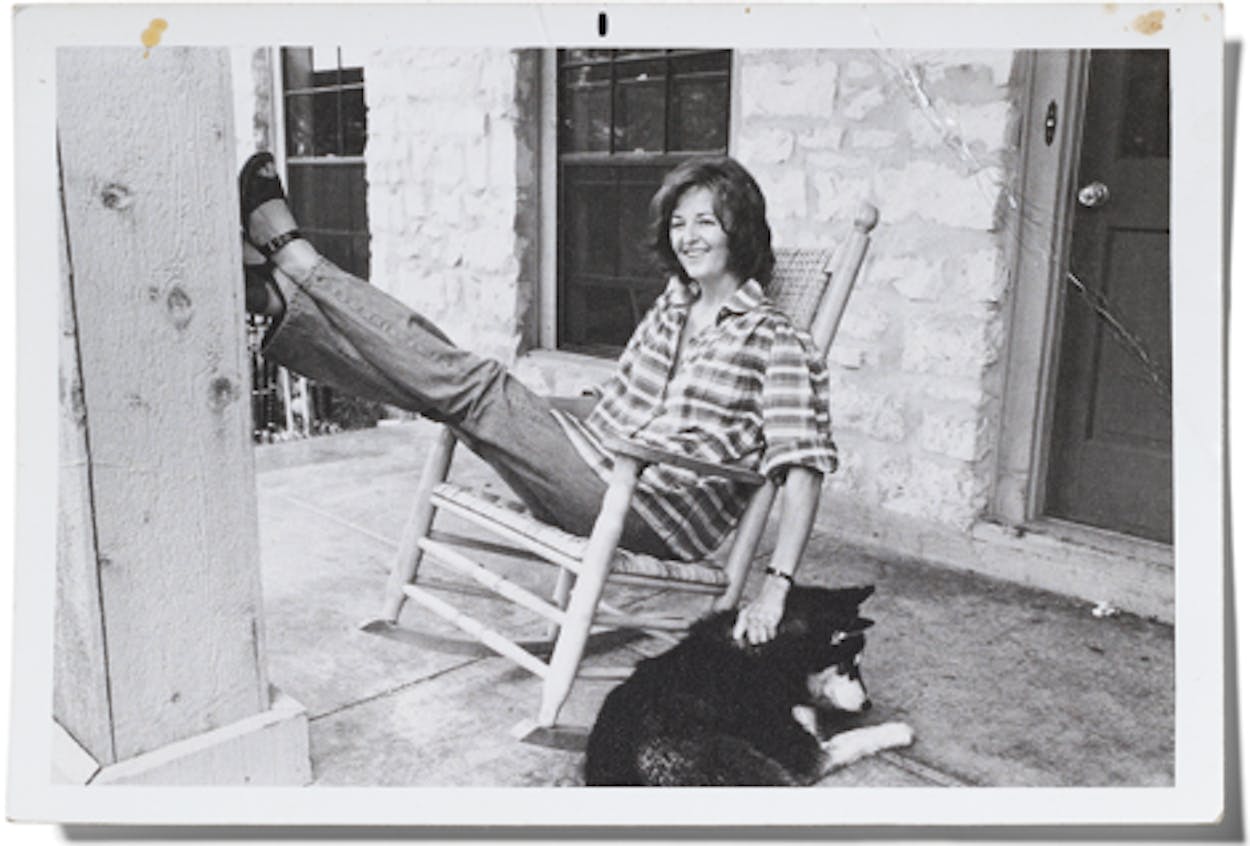

When we packed up and left Kentucky for Texas the second go-round, I was in high school, and this time we moved to Austin, a green and hilly city with lakes for sailing and an icy spring-fed pool for swimming. Those old years in Midland seemed like long-ago postcards sending bits of lore: Horned toads can be frozen solid and break off their tail and you can put them on the stove and they’ll hop away and grow another one. This time I settled in, went to the university, got married, had my family, and—in time, a mighty long time as I recall it—became a Texas writer.

In my first novel, Armadillo in the Grass, the woman narrator, an artist in Austin, sculpts animals. She also feeds them outside her kitchen door at night, just as I myself had done with a husband and small children, observing the habits of the raccoon and the possum—learning firsthand the feel of an almost seamless Texas world where the indoors and the outdoors are somehow always in tune.

I took this knowledge with me when, after 38 years in Texas, I moved East. In Westchester, New York, where I lived for 13 years, I fed raccoons under a flowering pear tree. I remember sitting on the front steps of my small house next door to a Methodist church at midnight, seeing a mother raccoon round the corner and leap straight up in the air with delight at the sight of the whole raw egg I’d left in the yard for her. And within a week of arriving in Vermont, in 1995, sure enough, a possum appeared by the glass back door. I mentioned this to my new husband, who said: We don’t have possums in Vermont. But of course they did—here and waiting for someone who knew their ways. Knew how they loved grapes and bananas, knew how they altered their smell when a dog wandered nearby. I spoke Texan to them—and they come around still. Each year there’s a slight learning curve, passed down to youngsters from their elders: In the winter you can’t come to the door the minute the sun goes down, that’s only 4:15 and not yet safe; in summer it’s best to wait till after ten.

Now I converse with a family of crows who keep their population at four and who let me know when anyone walks on the property. They used to recognize my husband’s Audi when he drove home, and set up cawing loudly to let me know and because that meant a late-afternoon treat of unshelled peanuts. Though he’s gone, they still salute his old car whenever his son drives by down our street. When the snow is three feet deep—as it was this year—those warm-blooded animals who tunnel under woodpiles know I’ll clear a feeding patch of ground for them, and those in the fir trees who flock together for sleeping in the winter know they will find the bird feeder full.

I cannot shake these ties to Texas, no matter where I live. I have set ten novels in the state, five of them as an expatriate. I can still see the country west of the 98th meridian, where I owned a faux German farmhouse near Wimberley in my single days and which I conjured for Group Therapy while living in New York. I wrote Ella in Bloom in Vermont after the death of my parents. Austin had gotten bone-dry, and I kept thinking of my mother’s roses and how she would’ve fretted and wilted herself. Yet working on the novel I’ve just finished, “I Knew Your Mother,” I have never felt more viscerally connected to the land. While my two fictional families carried on their intergenerational love affairs in Austin, Amarillo, and the Hill Country, I tasted the dust in my mouth and felt the hot, parched air on my face. Worrying about the water table, I saw the cattle put down when the forage dried up and got too expensive to irrigate, saw one hundred days in South Texas without rain head toward two hundred, pictured abandoned cars jutting out of shallow Lake Travis and ducks quacking in the Monte Vista neighborhood of San Antonio, looking for a creek that once flowed nearby. The night I rose up in my bed before dawn, threw off my covers, and shouted aloud, “It’s raining, it’s raining,” the drought had broken.

Last week, I had lunch with a new writer friend at a cafe that looks over the lake and has a nice strip steak, and she asked me if I considered myself a Vermonter. I said no, that though I lived here and this was my home now, I’d left my kin and my feet in Texas.