This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

All is not well in San Antonio.

Rupert Murdoch, media baron, owns newspapers on three continents. One day in 1973 the 42-year-old Australian breezed into Texas, met San Antonio Express-News owner Houston Harte at the airport’s Continental ticket counter, signed an option for $18 million, and then, says Harte, “flew away to wherever he was going.” By December 1973, for a final price of $19.7 million, both the morning Express and the afternoon News were his. And that, San Antonians want you to understand, is when the trouble began.

Murdoch’s two newspapers share facilities, including newsroom and presses, in the granitic old Express-News Building on the unfashionable edge of downtown. Two blocks away sits the afternoon competition, the Hearst Corporation’s Light, which for years held the perverse distinction of being Texas’ most sensationalist daily. No longer. Its local rivals, particularly the News, now pour forth Murdoch’s flamboyant brand of journalism, which in sheer delirious excess easily surpasses anything seen in Texas letters before.

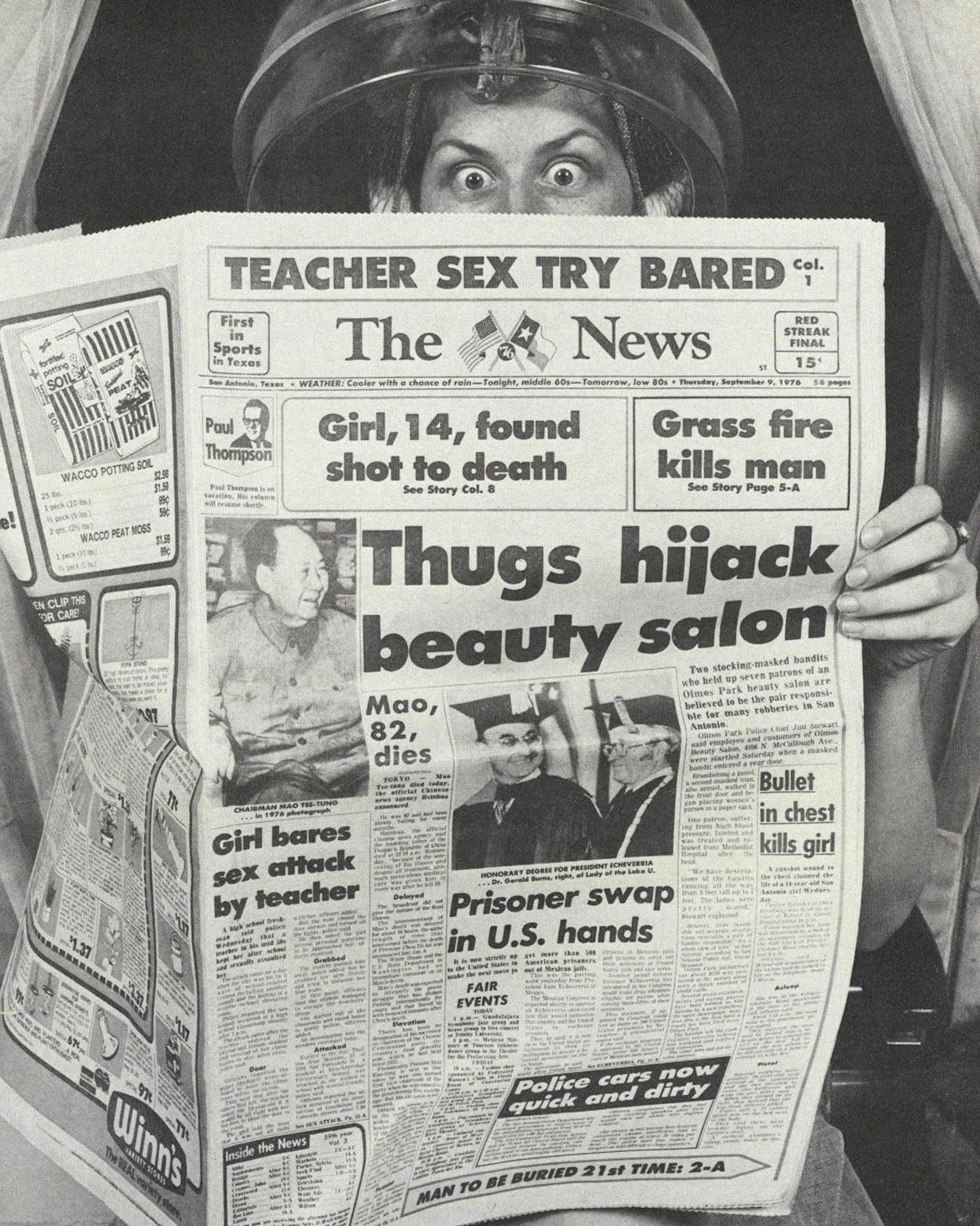

Readers of the News are learning things that five years ago they never dreamed they might be privileged to know: NUDE PRINCIPAL DEAD IN MOTEL, for example, or ARMIES OF INSECTS MARCHING ON S.A. The front pages regularly impart disconcerting information: HANDLESS BODY FOUND. Or SCREAMING MOM SLAIN. Or UNCLE TORTURES TOTS WITH HOT FORK. Occasionally there is a welcome dab of reassurance: POLICE CORRAL MAD ARSONIST. “Mad” people in general have begun to figure visibly in community affairs: the arsonist was replaced within a week by a MAD DRIVER who, said the day’s lead story, STABS CYCLIST. The columns of the paper are populated by an unforgettable (and recyclable) cast of characters: tots, oldsters, thugs, nudies, grannies, moms . . . Daily rape stories have been de rigueur. National and international affairs—never a staple diet for San Antonio’s newspaper-reading public anyway—have submerged with scarcely a burble beneath this tidal onslaught of previously unremarked local woe.

The River still flows, the tourists still gawk, but nothing has been quite the same since Rupert Murdoch came to town.

The good people of San Antonio want you to understand that they do not approve of this situation. They view the News with the same beady-eyed fury that their counterparts in, say, Lamesa might extend to the presence of a Magic Tickle Massage Parlor: it is an embarrassment, a monstrosity, an outrage, and the good people of San Antonio are mortified. “It’s an insult to our community,” says land developer Jim Dement. “Strangers—and I deal with a lot of them—come to San Antonio, and right at the airport the first thing they see is a newsstand with those big red headlines. By the time they get to my office they’ve read a little bit and they say, ‘My God! What kind of city is this? You guys are sick.’ ” Buick dealer Charles Orsinger regards the News as “a newspaper that makes you mad many, many, many times. It goes in for sensationalism at the expense of good reporting,” using stories which “wouldn’t be the lead story in any city except here, and in that paper.” Chief of Police Emil Peters has groused to the Los Angeles Times that the crime and sex stories are “overplayed and not deservedly on page one. They make the city appear to be a crime capital.”

The city’s largest school district cancelled a special program using 6000 copies of Murdoch papers partly because the contents were judged unsuitable for use as “classroom tools.” Proud-spirited San Antonians, already burdened with the difficulty of shielding impressionable visitors from the ambulance-chasing television news, despair when faced with the almost insuperable task of hiding the newspapers too: there on every street corner, lounging in a surly cluster like little plastic-visored steel Hell’s Angels, leer the vending boxes. The Riverwalk, where sales are tacitly banned, is the only refuge.

Murdoch, who seldom visits San Antonio these days, has left his papers in the hands of a trusted hometown lieutenant, Express-News editor and publisher Charles O. Kilpatrick. For 26 years Kilpatrick worked his way up through the Express-News ranks, becoming, under the Harte-Hanks regime, a respected local figure with ties to the city’s liberal Democratic political faction. Now he is besieged by critics. People who know him divide into two camps: those who think he hates what he has to do and suffers through every minute of it, and those who think he’s enjoying himself quite well. But no one can be certain because Kilpatrick, left to fend for himself, is drawing further and further into a shell. He refuses to discuss the papers with other newsmen and firmly declined to be interviewed for this story. Though he patiently receives delegations of disgruntled advertisers, informing them to their sorrow that the papers have no intention of changing their ways, he has fired off angry letters and threats of libel suits in response to criticism from such disparate sources as the Los Angeles Times and local radio station KITE.

The whole News affair has inflicted a painful wound to the civic pride of two groups with unmistakable clout—the old-money social establishment and the new-money growth-oriented business establishment. Rumors of organized moves to buy Murdoch’s papers circulate persistently, as do stories that someone is on the verge of introducing a competitive daily.

The tales are elusive. “I don’t know whether it has much substance,” says Jack Skipper, an associate of former Mayor Charles Becker, “but there’s been talk the last couple of years about trying to start another newspaper that was owned and run by responsible business people in the community to print the other side of the news.” Last year Ford dealer Red McCombs bought the Herald group of suburban weeklies and is, in a friend’s words, “trying to print good news.” On October 1, McCombs and his two partners took over a small downtown sheet called the Commercial Recorder, which reports court happenings and the like. Though he denies any intention to make the Recorder into a major daily, McCombs acknowledges that his group plans “to expand upon its contents with some editorial space that isn’t used now.”

The only identifiable effort to buy out Murdoch took place two years ago. Two-time Republican congressional candidate Doug Harlan assembled a group of “local people, non-local Texas people, and out-of-state friends of mine” who were in “oil, ranching, banks, and some rather large businesses” with the idea of making an offer to Murdoch (or, alternatively, to the Light). His goal was to publish a statewide top-quality newspaper right there in San Antonio. “None of the papers was actively on the market,” Harlan says, “but everything is for sale if the price is right.” The problem was, the price wasn’t right—in fact it was “about double what it should have been,” several million more than Murdoch had paid the year before. “There was lots of support for my idea in theory,” he says, “but when it came down to dollars and cents the support disappeared.” But the idea will not die. “I would love to see this paper owned by local people,” says Jim Dement, “because I think then it would be a responsible newspaper.”

Readers accustomed to more conventional newspapers may be taken aback by these vehement reactions. But then, they probably haven’t encountered all that . . . Murdockery . . . unless they happen to be addicts of weekly supermarket tabloids like the National Enquirer, the Tattler, or the Star (which is Rupert Murdoch’s own entry into that odd field). On the streets of San Antonio, however, there is no mistaking the News. With its red and black ink, exclamation marks, boxes, arrows, underlining, and Second Coming headline type, its cluttered front page looks (as Time observed) like an earthquake hit the composing room. The visual clamor is so great that on some days less than twenty lines of body type—“news”—can be found above the page-one fold. Serious world, national, state, or even local news stories are—well, they aren’t. On one randomly selected day this summer (September 7) less than 25 per cent of the non-advertising linage was devoted to hard news, compared to 66 per cent on the same day in the Houston Chronicle, 66 in the Dallas Times Herald, 41 in the Austin American-Statesman, and 55 in the Fort Worth Star-Telegram. By contrast, the Express, which optimistically calls itself “Texas’ greatest morning newspaper” but isn’t, comes far closer than the News to providing decent national and international coverage, along with some occasional worthwhile investigative reporting.

Both papers are striving to display the “populism” that staffers think Murdoch expects of them. There is an obvious class consciousness to their aggressive crusades against Coastal States Gas and Southwestern Bell Telephone, a self-congratulatory sympathy for the little guy. By taking after the utilities with an Ugly Stick they are doing something that newspapers in most Texas cities have long been disinclined to do. As with so much else, The News is far readier than the Express to cut loose with inflammatory damn-the-torpedoes rhetoric. Nowhere is this more evident than in the periodic salvos of the News’ blunt-spoken, readable front-page columnist, Paul Thompson. A sample:

OSCAR WYATT, WIFE

PRESIDENT GUESTS

So guess where your old chum Oscar Wyatt of Coastal States was hanging out on July 4?

On board the U.S.S. Forrestal, if you can believe it, with Gerry and Betty Ford, Henry and Nancy Kissinger, the Dukes and Biddles of Philadelphia, Nelson and Happy Rockefeller, and the whole dadgum royal family of Monaco.

. . . . The Great One’s latest adventure with your money . . . has to be the most spectacular scene the Wyatts ever horned in on during their many years of unabashed social climbing. . . .

Meanwhile . . . some of Oscar baby’s local black customers were paying their utility bills with nickels, dimes, and pennies.

But it is by no means just politics that makes the News the News. Like the supermarket tabloids, it is a treasure trove of trivia, violence, shaggy-dog stories, and the absurd. It thrives by giving prominence to tidbits that other newspapers discard or bury as fillers: a man who converts abandoned refrigerators into doghouses, a Japanese appeal for 100,000 four-leaf clovers, an 88-year-old woman married for the sixth time, the wreck of a pickle truck in Michigan, or the escape of two pet snakes aboard a German airplane. In the world of Murdockery, dental work on a lion merits photo coverage, and readers must see a close-up of the man with the longest moustache in Taranto, Italy.

Nothing is too remote to escape the News’ notice: both the crazed handiwork of a Detroit medical examiner who ran amok with a scalpel in his morgue (CORPSES FOUND MUTILATED) and the ingenuity of a Rhode Island mayor who wants to bombard skinny-dippers with itching powder (TOWN MAY SCRATCH NUDISTS) have been deemed worthy of front-page attention.

Perils of all sorts, preferably gory, unfailingly attract the eye of the News’ sardonic managing editor, Bert Wise. They range from staple, garden-variety misfortunes (TWO OLDSTERS FLEE FLAMES, THUGS ROB TWO STORES, WIFE SOBS FOR DYING HUSBAND) to the once-in-a-fortnight tragedic masterpieces:

AX ATTACKER

KILLS SLEEPER

and:

Slain Girl’s Parents

Bare Teen Scene:

DOPE AND DEATH

On any given day, in fact, the News can find and print enough violence to make the Alamo City seem like Guernica.

Calamities that befall cripples always provide succulent opportunities, not only for simple, unadorned pathos (3 ROB SICK WOMAN), but also for broader despair over the human condition, like the story that dominated page one on August 5:

MEAN BANDITS

ATTACK INVALID

The meanest bandits in town robbed an invalid man and then broke his four-legged walker, leaving him sprawled in a park near downtown.

Because be was not able to go for help, the robbery of Bernie G. Roe went unreported for a half hour. . . .

Roe, police reported, was knocked to the ground when one of the terrible trio hit him in the face.

The three thugs took his wristwatch, a gold horseshoe ring, $68 from his billfold, and even his white western hat. . . . Police officers took him home.

Occasionally all the elements of a great Murdoch story congeal in one headline: a central character who is well known to the public, malevolent forces lurking in the background (preferably capable of striking again), and a touch of the unexpected. On July 12 the nighttime burglary of a prominent San Antonian’s unoccupied residence produced a lead story so compelling that it pushed aside the Democratic National Convention:

THUGS ROB

EX MAYOR

BEAT DOG

The vastly improbable is also a good bet:

BEAR SCARES

2 TEENAGERS

An ugly-faced bear was spotted by two teenagers out fishing in a stock tank south of San Antonio Wednesday night.

But the bear that scared the two youths was in turn scared away by three pet dogs, one a Chihuahua.

The paper excels in its handling of Mondo Bizarro material: the man killed by a bullet up his nostril, the Houstonian with black fingernails found dead “next to an open coffin that authorities say is used for love-making by two homosexuals” (‘DRACULA’ DEATH PUZZLING), the divorced husband who sliced his house in two with a chain saw, the man so moved by the Word of the Lord that he toppled into his swimming pool (BIBLE READER DROWNS). If the material is insufficiently bizarre, the News has greasepaint available, as it showed with the lead story of September 3:

WEIRDO TRIES

TO SEIZE GIRLS

A bowlegged weirdo was foiled here Thursday in his attempt to kidnap two junior high school girls from a grocery store parking lot. . . .

Humorless critics of the News complain that its stories often fail to deliver the gaudy facts promised by the attention-grabbing headlines. Connoisseurs of Murdockery respond that this is precisely what they like best about the paper. There is, they say, a delicious suspense in pursuing a headline like PARKS SPYING ON HIKERS into an article that turns out to say nothing more than that the Forest Service is using a photoelectronic counter to tally the number of people who use its footpaths. You feel sure when you start that the parks aren’t really spying on hikers, but until you read the story you don’t know what it is they are doing that would let a headline writer get away with saying so. Properly approached, reading the News can be much like working a puzzle, offering the same self-satisfying rewards if you guess right before reading the answer. SPORTS BANNED DURING CHURCH, a page-one banner, takes you to Frostproof, Florida, where the city council has adopted an “informal policy” of closing the tennis courts on Sunday morning. A story about the fate of a female Merchant Marine Academy cadet whose fiancé had been found at something less than parade-rest in her dormitory room becomes SEXY CADET REINSTATED. A simple wire-service report tabulating the total arrests of illegal aliens during the previous six months in four Western states (Texas not included) is cagily tucked under the front-page headline MASS ALIEN SEIZURE BARED. And, unforgettably, an AP story about the Harris County (Houston) Commissioners’ decision to spend another $80,000 on mosquito control is plunked under the headline AERIAL WAR SET ON KILLER MOSQUITOES.

Regular readers of the News would explain its skillful handling of the mosquito item by noting that the paper has a special fascination with insects, rodents, vipers, pestilence, and natural disasters. The lead story of August 23 exemplifies this in classic form:

DEADLY TICKS

INVADING AREA

A close reading disclosed that one case of Rocky Mountain fever had been diagnosed in Hondo, and that the victim was already “fully recovered.” The Tangshan earthquake of course provided an opportunity too good to overlook (CHINESE CITY IS WIPED OUT)—followed, inevitably, by the next afternoon’s HORDES FLEE NEW QUAKES. Before the last aftershock had settled, readers were invited to worry about the THOUSANDS FLEEING VOLCANO IN GUADELOUPE. An error in timing (was Bert Wise taking the day off?) allowed the August 17 edition to squander this promising story with the premature forecast VOLCANO READY TO BLOW; when it didn’t, there was no alternative except to drop the subject and turn, abashed, to something else: GULF STORM GROWS.

Beyond the headlines, there is the graver question of whether, in one concerned businessman’s words, “things are being made to happen in order to create news.” Reporters within the Express-News organization are openly skeptical about some of the stories that see print. One says flatly: “The Express and the News have both been using fabricated stuff ever since Murdoch took over.” The work of a now-departed staffer, Aziz Shihab, is most often cited in this connection. Shihab authored an expose alleging that Vietnamese refugees were operating a house of prostitution near Lackland Air Force Base. No one else was able to locate the house, and Shihab now describes the story as an exaggeration. He says the News sensationalized the story, wrote its own lead, and used his by-line over his protests. Shihab also was responsible for the story that a certain Saudi Arabian sheik wanted to buy the Alamo as a gift for his son. The story was carried worldwide, even drawing a declaration from Governor Dolph Briscoe that the famed landmark was not for sale. A search in Saudi Arabia, however, failed to turn up the sheik, and another search failed to turn up the son. Shihab, now a reporter in Dallas, says he found out about the whole thing from a Houston attorney who cannot be identified. Express-News publisher Kilpatrick has steadfastly refused comment.

And then there is the matter of the shinplasters. To historians of early America the term “shinplaster” means stacks of devalued, nearly worthless paper money; around the Express-News offices, shinplaster means slabs of advertising disguised as legitimate editorial news copy, set in the same headline and body-type fonts as regular editorial stories and lacking even the word “Advertisement” in inconspicuous type nearby. The News uses shinplasters by the truckload, though reputable journalists consider the practice utterly low-rent. “How it works is simple,” says an Express-News reporter. “A large store will guarantee X number of pages of ads and get a certain amount of shinplaster as part of the deal.” Thus, the News’ unsuspecting readers encounter such “stories” as J. C. PENNEY OPEN IN WINDSOR MALL, NEW JOSKE’S IS A ‘NATURAL’ FOR SHOPPERS, and NEWEST DILLARD’S GETS RAVES. Sometimes the “stories” occupy a full page. The Joske’s tout, with subheads like JEANS FEATURED, was shamelessly followed by a two-page advertising spread. The caption for a “news” photo of a man spraying a roof explains that “A Monoflex roof can save you hundreds of dollars by reducing your utility costs. . . . Stop by Coating Specialists at 1185 Warfield or call 349-6204 for a courteous estimate.” The News became so overwrought about the opening of Windsor Mall that it supplied front-page coverage two days in a row, plus a gushy editorial that praised the shopping center as an “elegant bonus” and fawned, “We congratulate the builder, Melvin Simon & Associates.”

The News’ inventiveness also extends to the contests that run, world without end, on its pages every day. Readers have been able to choose among the $25,000 Summer Sweepstakes (“Everyone’s eligible. Just mail us your Social Security number today!”), the $75 Mr. Bigfoot Contest (“Find someone with big feet . . . and send in the details”), the Happy Faces Contest (“If your smiling face is on this page and there is a circle around it . . . you have won $10”), the less-than-successful Rat War (“$50 and a plaque to the Bexar County resident who kills the most rats by Aug. 1. Dead rat tails at least three inches long should be taken on Fridays to Martin Mendoza”), and the What Should Be Done About Coastal States Gas survey, which to no one’s surprise rapidly turned morbid (“Take the suit to court ‘and skin Brother Wyatt as we do it,’ ” suggested one reader).

But if any single event could sum up the News’ style, it would be last summer’s What Can Charlie Brown Do Next Contest. Brown, a local disc jockey, had already attained celebrity status by spending nearly two weeks in a tiger cage at the zoo. (The fact that Brown occupied the cage in lieu of tigers, rather than with tigers, was not regarded as diminishing his achievement.) By inviting its readers to mail in suggestions for Brown’s next stunt, the News managed to create out of thin air a media event that could be—and was—manipulated for weeks. After days of sadistic proposals, the winning “dare” was chosen and announced on page one: to walk around Loop 410, a freeway that encircles San Antonio. Then more days of suspense: DEEJAY TURNS PALE THINKING ABOUT TREK. Then a huge map showed “Route of Proposed Charlie Brown Walk.” Then WALK TIME NEAR, CHARLIE’S NERVOUS. At last the Walk, with day-by-day coverage; and finally the front-page triumph: CHARLIE BROWN WHIPS LOOP.

There has, admittedly, been precedent for this sort of media-sponsored, self-promoting “news” story; back in 1889, Joseph Pulitzer assigned Nelly Bly to circle the globe while his yellow-press New York World drummed up suspense over whether she could beat the 80 days required by Jules Verne’s Phileas Fogg. But Pulitzer’s adventure had been done before, if only in fiction; Charlie Brown, by contrast, was “the hero of the hour . . . the first man ever to walk around San Antonio.”

Just so. And you read it first in the News. Indeed, without the News, you would not have read it at all.

“The News,” sighs an Express-News reporter in tones of infinite resignation, “is not a good newspaper according to everything you learn in journalism school.”

If the News is not a good newspaper, what is it?

The fact is that San Antonio has been smacked, as though with a custard pie, by a form of journalism heretofore unknown in these parts: the popular mass press of England. There has long been a sharp difference, says Trinity University professor of journalism Richard Gentry, between England’s “dignified, responsible press, and its popular mass press, which has always tended toward sensationalism.” England has given the world not merely Shakespeare and Samuel Johnson, but a mass press with a tradition that bears no relation to the lofty journalistic virtues of balance, objectivity, seriousness, and taste. The mass press goes well beyond American “yellow journalism” and tabloid antics. British newspapers like the Daily Mirror, the Daily Express, and Rupert Murdoch’s own four-million circulation Sun are basically just a form of wacky entertainment—the journalistic equivalent of junk food. They rarely pretend to be more. A Murdockian headline like LEE COED TO DIE SATURDAY is not meant to be a solemn announcement of human tragedy, but a momentary diversion, made all the better by virtue of its being sad: people secretly love to read about others’ misfortunes. “Responsibility” has nothing to do with it. The British mass press decorates the newsstands each day with pillow-sized “flyers” ostensibly conveying news, but actually designed to lure and deceive, all in fun (and profit). Occasionally the deception successfully breaks through to the level of pop art, as in the memorable 1964 London flyer for the story that Senator Edward Kennedy had been hurt in an airplane accident which killed his pilot. TED KENNEDY, it shouted, IN FATAL PLANE CRASH. The challenge of the flyer, as you have no doubt gathered, is to figure out what has actually happened without having to buy the paper: a coy game between publisher and reader. Murdoch has brought the flyer technique intact like some treasured icon to the streets of San Antonio. THE MOONIES ALMOST CAPTURED ME, shrieks one. THOUSANDS REFUSE TO PAY TRAFFIC FINES, hints another. NIGHTCRAWLERS DRIVE TOWN NUTS, warns a third.

Of course Britain’s Responsible press will have none of this. The Times of London, the Guardian, the Telegraph—they have better things to do. So do the U.S. newspapers that mold themselves on the American ideal of what good journalism should be—papers like the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Saint Louis Post-Dispatch, the Los Angeles Times.

The News, transplanted to San Antonio from England via Australia, simply thumbs its nose at the Responsible tradition. Should it, for good or ill, be viewed as merry nonsense instead of something that aspires to be the New York Times and falls short? Perhaps. Take its crime and violence and misery seriously and they soon seem tediously repetitive; take them as exercises in style and they become endlessly fascinating. Style makes the News what it is. Style: the ability to report something weird or awful with brevity, perverse aplomb, and wit. PLAGUE HITS TOT: finesse is everything.

There is an anecdote making the rounds in San Antonio. Reporters at the Express-News strenuously insist it is not apocryphal. On especially good and lurid news days, so the story goes, News managing editor Wise can be seen gamboling through his newsroom, singing cheerily to all who will listen: “This isn’t journalism: this is show biz!”

Yes?

Yes.

But is a major daily newspaper in the country’s tenth-largest city an appropriate stage for show biz? Murdoch himself answered that in a rare interview earlier this year, when he explained his newspaper philosophy to Los Angeles Times reporter Robert Dalios: “We’re not here to pass ourselves off as intellectuals. We’re here to give the public what they want. That’s what’s wrong with American newspapers. They’ve become monopolies and therefore have been able to afford the self-indulgence of intellectual showmanship. This is passing over the great bulk of the public and that is why you are finding circulations are shrinking. The thing that’s holding most circulations up is the readers’ interest in the advertisements. In monopoly towns . . . the public’s got no goddamn choice. If they want to know where the food bargains are, they’ve got to buy the goddamn paper. You can have all the intellectual material you like, win Pulitzer prizes, and say you’re great, but there’s no way of testing whether the public likes it or not.”

And how did Rupert Murdoch, Aussie, find out what San Antonio’s public wanted? Easy. “We studied what was happening in the town,” he says. “The most noticeable thing in the media was the popularity of the local [television] news shows.” Murdoch was able to drive the last two silver nails into San Antonio’s media coffin only because the lid had been all but tacked shut by his predecessors in print, radio, and television. Not only by Hearst’s successful, frenetic Light, nor by the steady diet of crime and violence on 6 and 10 p.m. TV, but also by radio stations that sustain listener interest by sponsoring Slapping Contests or attempting to drop eggs off the Tower of the Americas. Murdoch simply perceived what anyone with his wits about him could see instantly: San Antonio is a very special audience.

The horrifying fact, for those whose hearts throb with civic loyalty, is that Murdoch’s formula is working. The News has picked up circulation. Much of the gain is thought to be in the city’s vast west-side Mexican-American barrio. The Light, though still larger, has been the loser. (San Antonio is one of just five American cities that still have two competing afternoon papers—traditionally a flashier form of journalism than their morning counterparts because of their greater dependence on street sales.) From March 1974 to March 1976, these changes occurred:

- The daily News, up from 62,909 to 76,243.

- The daily Light, down, from 129,164 to 126,032.

- The Sunday combined Express-News, up from 135,162 to 160,080.

- The Sunday Light, down, from 177,497 to 174,394.

Former Express-News owner Harte says Murdoch “has done something we couldn’t do” with his impressive circulation gains. The Light, which for years was among Hearst Corporation’s most profitable newspapers, is widely rumored to have gone into the red for the first time in 1975.

By escalating the competition, Murdoch has made the Light look respectable by comparison. True, the Light also runs enormous headlines no matter what the news is; but serious news, not exotica, is ordinarily the lead story. True, the Light also gives prominence to local violence; but the chosen items are usually of more than incidental importance and are presented straight, without the News’ slathering prurience. True, the Light has sweepstakes contests, too; but underneath these superficials, it still manages to maintain a stubborn core of dignity. Not much: but some. Unlike the News, the Light is simply incapable of choosing THUGS HIJACK BEAUTY SALON as the lead story on the day Mao Tse-tung died. Does dignity sell in San Antonio? Look at those circulation trends again.

Murdoch’s material success at the Express-News has not been achieved without a price. Many of the papers’ best staffers have left, some gracelessly shoved out into the cold and others following disputes with the management over the full implications of Murdockery. Twenty-five-year veteran Capitol correspondent Jon Ford, one of Texas’ most respected political analysts, found haven at the Austin American-Statesman—but not, he says, before “they screwed me out of all my retirement benefits.” Former city hall reporter Joy Cook is night city editor at the New York Post. Express managing editor Ken Kennamer, whom some associates remember as “the only person who’d argue with Kilpatrick about news content,” left to become publisher of the Arlington Daily News. There are numerous others. One veteran desker of the old school has reportedly confided to his friends that life at the office “is like working in a whorehouse.” And many would share the lament of the young writer who complains, “It’s gotten to where you’re embarrassed to tell people you work here.”

Regardless of whether the News is a South Texas imitation of the British mass press tradition, and regardless of whether Rupert Murdoch is giving the public what the public apparently wants, the good people of San Antonio say the News is spinach, and they say to hell with it. What San Antonio really needs, they will tell you, is a newspaper that prints “good news,” one that isn’t “negative.”

“What’s the value of tearing a community down?” asks a leading banker. “Everybody knows there are sewage lines below the streets, but people don’t normally like to get down in them.” “Businessmen here depend on a positive image for San Antonio,” says Jack Skipper. “Gosh, we need business here so bad we just don’t know what to do. Yes, I would say the Express-News is a liability to this city as far as economic progress is concerned.”

“Every one of us,” says Jim Dement, “has gone down to talk to Charlie Kilpatrick about a decent paper. His attitude is, if you don’t want to see dirt in the paper, then the dirt ought to quit happening. Which is a dumb attitude: I have no control over knifings in bars and silly things that aren’t constructive. I try to be constructive every day in my business; I’m never destructive. When we’re trying desperately to bring industry into this community and raise the wages and the economics of the general public—I’m talking about the poverty-level worker who can’t afford to pay his utilities—well, we can’t keep spending money to bring economic development to San Antonio without help from the newspapers.”

Economic development. Positive attitude. A good many San Antonio businessmen really believe it. When a developer tells you that “constructive news should rate front page,” he means it. When a banker tells you that the purpose of journalism is “to lead people to a higher plateau of quality of life” by “attracting industry and creating jobs instead of printing stories that appeal to a man’s animal instincts,” he means it. San Antonio is a prime example of the notion that everybody and everything that matters, including the newspapers, properly belong at the service of whatever goals the dominant economic establishment has in mind. Rare indeed is the skeptic who, like the third-generation scion of an old Bexar County family, admits, “San Antonio has a pretty naive attitude about boosting business. It’s the bullshit capital of the world. They’re not being very realistic if they think a rape story is going to keep a new business from coming here.” Murdoch and his business critics are fundamentally at odds about what a newspaper is supposed to be. That is one reason why the blood feud runs so deep.

There is a second reason. Murdoch’s papers have power. Instead of using it to tell their readers to trust whatever the community managers are saying, they are using it to talk politics point-blank to the public. That, too, is the British mass press tradition; and the techniques of the News nearly anybody can understand: anti-Oscar Wyatt diatribes and garish, electrifying four-inch headlines like COUNCIL IS TOLD HIKE UTILITY BILLS and SUBURBS FIGHT UTILITY CHARGE. While such populist tub-thumping is plainly secondary to the routine merry nonsense and the goal of selling newspapers, it has been more than enough to scare the good people of San Antonio. “I went to a public hearing on the Lo-Vaca case the other day,” says a local banker, “and it was frightening. ‘Kill ’em! Destroy ’em! Get blood!’ The rhetoric was straight out of the Express-News.” Murdoch’s papers have, in an awkward way, emerged as a new and rival political force, threatening the establishment’s let-us-handle-it attitude.

Talk for long to the good people of San Antonio, and you become aware of their one great all-but-unspoken fear: the News is stirring up the city’s poor, especially the racial minorities who presumptively compose its principal readership. You may be told: “We’ve got a lot of little folks in this town that can’t read English. They know certain words. They don’t do nothing except read the headlines. They don’t understand most of it, but they believe what they see.” All this talk of violence every day may just . . . rub off. All this shouting about politics and utility rip-offs may just . . . wake up that sleeping giant. The city’s east-side blacks and, even more, its 250,000 west-side ethnic Mexicans, 20 per cent of whom are thought to be aliens, someday may just . . . run wild, coursing up San Pedro flailing copies of the News, robbing stores, snipping telephone wires, attacking invalids, and torturing tots with hot forks. ARMIES OF INSECTS MARCHING ON S.A. . . . Soweto-beyond-the-MoPac . . . Ka-boom.

These fears are usually couched in oblique phrases like “avoiding a Crystal-City-type environment” and “our unstable political situation.” They draw forth circumlocutions every time: “I think what the News wants to appeal to is—well, I don’t want to use that word, because it sounds like I am judging a certain portion of the population—I think they are trying to affect a sales group of ignorant people.” Point out that England has been exposed to some form of Murdockery for generations without succumbing to anarchy and you will be told that England is just . . . well . . . different. The fears are real: something may come along and light the powder keg on which the good people of San Antonio think they sit. Why is Charlie Kilpatrick playing with matches?

More than any other city in Texas, with the possible exception of El Paso, San Antonio society is a veneer of predominantly white, economically well-off whites atop a much larger base of predominantly poor Mexican-Americans. The News—its violence, its politics—has shattered the tranquility of white San Antonio’s middle-class enclaves as has nothing else before. You can always turn off the TV, but the News is loose on the streets. San Antonians of this generation see in Murdoch what their great-grandfathers saw in the shifty-eyed stranger who sold whiskey to Indians.

They are furious with him for being, as they see it, so foolhardy. But that is not the worst of it. Deep down, when they put their vague fears of riots and race wars aside for a well-considered rest, they are even more furious because Murdoch has spilled, for all the world to see, the secret of their city. The News has forced San Antonio’s booster-oriented, economically productive leadership, as well as its inbred high society, to face the fact that their city is not really the sort of place they have tried to pretend it is. The orthodox view—that San Antonio is a subtropical paradise of broad avenues and stately homes, a sophisticated city where people divide their time between the McNay Art Institute and the opera, dining at La Lou, strolling along the Riverwalk, pausing now and then to window-shop the latest fashions at elegant malls, one of America’s Four Unique Cities—the orthodox view won’t wash. San Antonio is indeed the most beloved, the most Texan, and in many ways the most beautiful of the state’s cities, but it is also the city where 19 per cent of the inhabitants live below the poverty line, where 82 miles of streets are unpaved, where heroin addiction is the highest in the state, where the rotting downtown core is almost beyond rescue, and where 25 per cent of the housing is substandard. Time, money, and power have passed it by, like Vienna. Its good people are for the most part decent folk who love their city and want to see it nursed back to health with the only methods they have allowed themselves to consider. For them, the worst news is not SCREAMING MOM SLAIN, but the fact that San Antonio is the kind of place where such a headline dependably sells newspapers. If anything keeps new businesses away, it is not the rapes, but the audience that wants to read about them—something even Murdoch cannot change.

In their heart of hearts the good people of San Antonio have known this all along, of course. The orthodox view was a useful front so long as the truth remained their family secret. Few among them have had the courage finally to admit out loud, in the words of one old-line San Antonian, that “the News is only a reflection of San Antonio. San Antonio is a poor, violent, crude town.” They cannot forgive Rupert Murdoch for letting the world know that.

Where is the News headed?

Some San Antonians think it will eventually have to come around. “One day the major advertisers will get their gut full of it, when the economics of the city start to worsen,” predicts one business critic. Maybe. But again maybe not. Advertisers need newspapers as much as newspapers need advertisers. And in any event, in the pre-Murdoch days there was little pressure to have a quality newspaper; now there is pressure, but only to get rid of a “bad” newspaper that prints “bad” news. Nobody is complaining about the shinplasters.

Bravely, life goes on in the afflicted city. The River still flows, the tourists still gawk, and each day brings new drama to the corner vending boxes. Changeless, the questions remain.

Will the good people of San Antonio unite to buy the News?

Will the sleeping giant awake?

Will the oldsters escape the flames?

What will Charlie Brown do next?

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- San Antonio